Field Marshal Montgomery famously said that ‘the great thing about doing no preparation is that failure comes as a complete surprise’, and failure does indeed come as a great surprise. But why should that be, why does it catch us unawares and make us realise that the situation we are in is different, quite different, from what we’d thought? The element of surprise is important because there isn’t typically a slow, gradual slide into failure. Again and again managers, people, businesses, organisations think they’re all right, then all of a sudden, too late, they realise they are a long, long way from that. They are not progressing gently downhill but cascading unstoppably.

When I first became CEO of an organisation that everyone agreed was failing, I noticed some unusual features: widespread misjudgement of the problems faced, a failure to respond to what the external world, customers and stakeholders were saying, blindness to the consequences of major actions and no one ensuring that staff had the right skills, were directed in the right way, and were monitored to see that they actually achieved. Dealing with my second failing organisation, I realised there were recurring features: firstly the discontinuity between performing satisfactorily and failing to do so, and then the realisation that there was a common path that organisations went through when they went into deep failure and lost control of their own destiny.

I’ve seen at close quarters more than 20 organisations experiencing failure. I’ve been able to refocus on key aspects of failure, confirm the repeating pattern and understand what is common to all of them. I have also checked this out with colleagues who have experienced failure directly by being in the middle of failing organisations, or indirectly as outside observers and rescuers.

My conclusion is that there is a characteristic path of organisational or business failure with characteristic features and pitfalls, and a right way to get out at the other end. I’ve mapped this on a curve which I call the Yosemite curve. I call it that quite simply because it reminds me of the asymmetrical profile of that stunningly beautiful Californian valley with the steep face of El Capitan to the left.

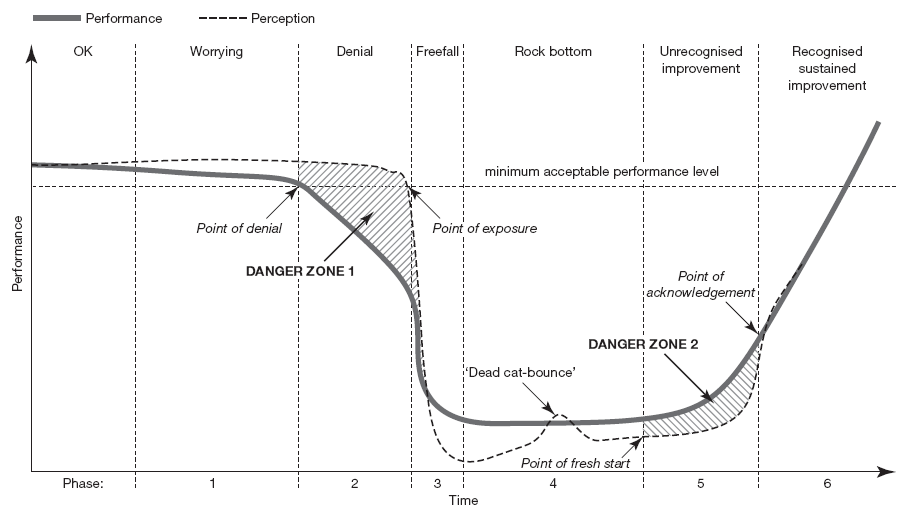

I divide the failure process into six different phases. To analyse these phases I map the performance of an organisation over time against acceptable, required performance. The key to unlocking the failure pattern is not just to draw a graph of performance but to compare it with something else that is closely related to performance and ideally should be identical to it, but isn’t necessarily. Quite simply it is what the performance is thought to be, i.e. the perception of performance. I decided to map ‘actual performance’ and ‘perceived performance’ together because what I kept seeing was a marked divergence between them as failure hit an organisation, as it went through failure and as it tried to come out of failure. It struck me that there was a key message in this. The graph is on the next page.

The graph divides neatly and naturally into time periods. The first is the period of acceptable performance. I call this phase zero as it relates to the normal and normally permanent state of affairs. Phase 1 is when there starts to be a divergence, however gentle and gradual, from that state, where an organisation starts to struggle. Phase 2 covers the period when it is already hurtling into failure but this is not universally apparent. Phase 3 traces the period when the failure is public but remedial action isn’t taken. Phase 4 describes a period of stability, but a very dismal stability with completely unsatisfactory and unacceptable levels of performance; the organisation is at rock bottom. Phase 5 describes the first stirrings of recovery and then of steady improvement. Phase 6 describes acknowledged improvement and the regaining of autonomy and embedding of good performance, but this time with an upward momentum partly derived from the experience of what has happened and the insight derived from that. This typically distinguishes this phase from the performance prior to failure.

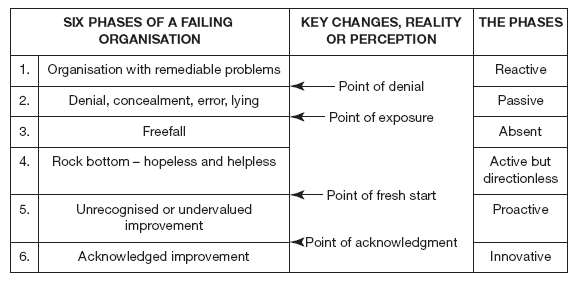

The six phases of the failure process

I set out the six phases in the table below, corresponding to the graph, and highlighting four key points where the failure path ‘turns’.

- The first, the point of denial, is where performance is no longer acceptable but this is covered up or denied: phase 1 turns into phase 2.

- The second is the point of exposure where any cover-up is revealed: phase 2 turns into phase 3 and the organisation hits rock bottom (phase 4).

- The third turning point is when there is a fresh start and the organisation begins to recover: phase 4 becomes phase 5.

- The final turning point, the point of acknowledgement, is the point at which it becomes generally and widely recognised that the organisation is now healthy and thriving, performing as it should: phase 5 turns into phase 6. How the organisation is being managed through all this is vitally important, so I have characterised the management approach being taken in each phase.

The six phases of deep failure

Here are some key guiding assumptions that underpin the graph:

- Every business, every organisation with significant tasks, from time to time faces difficulties and problems that it cannot immediately resolve. These are part and parcel of its daily business and do not mean the organisation is failing. Each year, it is typically quite a challenge to make enough profit (or, in the public sector, balance the books) and meet the key targets that are seen as defining success. Sometimes soundly functioning organisations will miss a particular target.

- But there are businesses and organisations, which are not only not coping with difficulties but have lost the ability to do so.

- An organisation’s or a business’s performance and the perception of its performance should be identical or at least reasonably close.

- When the two diverge, with performance materially worse than it seems to be, it is a strong indication either that the business or organisation is already failing or that this divergence will actually become a cause of failure. This is my key finding.

- After a business has ‘failed’ and is starting to recover, the perception of its improving performance typically lags behind the reality. This is dangerous and a brake on improvement.

Phase 1: Struggle

Organisations manage satisfactorily. Organisations struggle. Organisations have problems. But the first defining point in moving from (normal) struggle to (abnormal) failure is the lack of acknowledgement that significant problems remain, are mounting or even exist. This is the point of denial. This is when an organisation with remediable problems (phase 1) starts to become a failing organisation (phase 2). It moves from struggle to denial, from puzzlement to concealment, from dismay to disinterest. This is disastrous.

People can walk into this. In some organisations I have worked in and with, with a glaring financial problem, while detailed plans have been put together to remedy it (still in phase 1 and aiming to stay there), the plans remained theoretical, they were not realistic, they were designed to impress and mollify others rather than to be realistically implementable and achievable. The result: initial acknowledgement begins to turn into denial and/or delusion, and as these plans fail or fall short, a little time has been gained but that time has not been used as it should have been, to get working on the real, feasible solution. The business has now moved to the brink of phase 2.

At the next iteration the same thing is likely to happen (plausible but unrealistic plans), but this time there will be more cynicism among those asked to implement the plans and even less scope to do so. It is now virtually inevitable that the business will be plummeting into deep failure (phase 2) because the only way out, admitting difficulty, seeking external aid and working on a different approach, is not being tried and is closed off.

Phase 2: Denial

In phase 2, the organisation is on a very dangerous declining trajectory – perception and reality have now separated. Those within the organisation who could highlight the problem choose not to do so. Those who ought to be becoming aware of it are not. In the meantime the causes are magnifying the problem. This phase can go on for some months but it is a very unstable situation and it is virtually inevitable that it will come to an end for one of the following reasons:

- Those responsible for the problems but who have actually given up on them will flee.

- Someone will blow the whistle on the problem, causing those responsible to be removed from the scene. For example, according to a report in the Guardian dated 26 March 2011, ‘The managers of Madonna’s charity in Malawi have been ousted after they squandered $3.8 m on a school that will never be built. The damning audit came as Raising Malawi confirmed that it has scrapped plans for a $15 m elite academy for girls. In its report it [the Global Philanthropy Group] said the [CEO’s] level of mismanagement and lack of oversight was extreme.’

- The problems will become so obvious and large that concealment and denial will no longer be possible, again causing removal of those responsible. There are numerous recent examples of this in the world of city trading: Nick Leeson, Barings Bank, losses $1.4 billion (1995); Yasuo Hamanaka, Sumitomo, losses $2.6 billion (1996); John Rusnak, Allied Irish Banks, losses $691 million (2002); Jérôme Kerviel, Société Générale, losses $6.3 billion (2008); David Higgs, Credit Suisse, losses $2.65 billion (2008); Kweku Adoboli, UBS, losses $1.5 billion (2011); Bruno Iksil in London and his boss, Ina Drew, known as the Queen of Wall Street, JPMorgan, losses of more than $2 billion (2012). (Figures as reported in the press).

There are two variants of the perception and reality split which happens in this phase, the first based on deception, and the second – the more common – based on delusion.

Phase 3: Freefall

When an organisation gets into this position, it is awful and it feels awful – for everyone. No one knows what to do. No one is trusted. The organisation has lost coherence. Blame is everywhere. The organisation has lost autonomy and is directed what to do.

I was asked to help a well-known organisation facing adverse publicity about a really problematic issue. A few days later, one of my staff was told by a senior manager working there, but accountable to an organisation outside it and overseeing its problems, that they were totally preoccupied in dealing with the immediate problem. At that moment it would be highly inconvenient to have anyone else coming in. I rang the CEO. His response was ‘Yes, I am sorry about that. But you need to understand the position we are in. We have people from outside directing this process. We are not in control of it. Where we are now, I need permission to go to the toilet, and I am the CEO!’

What does it feel like in a failing organisation? There will be a siege mentality because there will be a siege. A sense of rudderlessness, hopelessness and helplessness will permeate everything. People have stopped believing things can be done. They will have retreated into their corners and be doing what they can there and nowhere else. The organisation will be very confused about its current obligations, but they are very likely to be impossible to meet.

So, there seems to be no coherent way forward: the previous rationale for doing pretty well everything is likely to have collapsed with nothing to replace it. At this point not only is there no direction in the organisation, there is no pretence of it. As underlying problems are not dealt with they get worse at an alarming rate. This is the phase in which everyone in the organisation and everyone outside recognises that something is drastically amiss.

What had seemed just about acceptable is shown suddenly and spectacularly to be completely unacceptable, as the true state of the organisation is revealed – and that it is dramatically different from what was thought.

When this happens – be it in the private sector, as with Northern Rock and Enron, or in the public sector, as with the publication in 1998 of the report into the deaths of several children undergoing heart surgery at the Bristol Royal Infirmary, in which it emerged that warning signal after warning signal had been ignored – a furore follows.

Take the case of Bear Stearns. In March 2008 the US financial giant collapsed. The bank’s value plummeted to $250 million compared to $14 billion the previous year (and the share price fell by a factor of 30 in a month), leaving a failed shell of an organisation. But up until the week before the collapse, people at Bear Stearns, including its CEO, were saying that ‘everything was fine’ and it faced no liquidity issue. Within a very short period of time its CEO resigned, and it was preyed upon and swallowed up.

Revelations about the manipulation of LIBOR rates at Barclays emerged in the summer of 2012, and clearly demonstrated the Yosemite curve’s ‘point of exposure’. Within a week of them becoming known the CEO, Chair and COO resigned, the revelation caused a firestorm in the media and in Parliament – with the contagion spreading to a slew of banks, indicating a deep failure across the banking system. On 17 July 2012, the Governor of the Bank of England poured further fuel on the flames as he testified before a parliamentary committee about warnings he had given and others’ failure to listen to them: more exposure.

That day and the next vividly demonstrated that the point of exposure happens a lot. Across the Atlantic, a Senate subcommittee was grilling HSBC officials about enormous and routine money laundering, notably of drug money. And right in the middle of the hearing, at a true point of exposure, the Head of Compliance at HSBC resigned while giving his evidence, clearly because of what he was revealing.

Still the same day and back across the Atlantic in England, the CEO of G4S was being grilled by another parliamentary subcommittee for his company’s failure to provide enough security staff for the London Olympics, with everyone only realising this about two weeks before the Games began. In addition to receiving withering personal attacks from MPs, the CEO and G4S were mercilessly criticised across the board by all the media and, given that the Olympics are a worldwide phenomenon, across the world, with devastating effects on their reputation.

Quite simply, outsiders lose confidence at a stroke and, with it, trust. They feel the organisation is hopeless in all respects. That’s why:

- There were queues outside Northern Rock after its finances unravelled, with investors panicking to withdraw their money, irrespective of all assurances that it was safe.

- Patients wanted to go anywhere but Maidstone Hospital after 90 patients had died after contracting the ‘superbug’ Clostridium difficile.

- I was told when taking over my first failing organisation ‘At its best this hospital is never more than mediocre in anything it does. ‘Yet there was much about the hospital that was far from mediocre, as I quickly discovered.

Such reactions conspire to make matters worse, by causing the failed organisation to be blamed for practically everything, including much it may never have been guilty of. By the time their failings had been exposed, the Northern Rock savings were actually secure and the patients at Maidstone were as safe there as anywhere else.

Blame culture at the Royal United Hospital, Bath

I had a taste of being blamed for everything at the Royal United Hospital, Bath. I’d been there for a matter of days when I was asked to attend a meeting as sole representative of the hospital with our partner organisations and the Health Authority, the senior organisation to which we were all accountable. The meeting itemised a series of problems. At the end of each discussion item, people in the room turned to me and said ‘so what are you going to do about it?’ I began to realise that there were ten people in the room, only one of whom had no responsibility for the problems Bath was facing: that person was me. It was then I realised that in order to move Bath forward I had to alter the terms of engagement with our partners and others to give us the freedom to move on and not to be blamed for things that we were not responsible for. Although it was hard, I did just that – and it made a huge difference. The hospital, and everyone working in it, could move on.

What causes exposure is usually one of three things: a discrepancy on resources (meaning money); under-achievement on outputs (volumes, targets); or a failure in terms of outcomes, usually involving harm, lack of safety, effectiveness or quality. The money examples are everywhere but famous recent ones include the American financiers Bernie Madoff and Allen Stanford who took investors’ money and spent it on themselves rather than investing it, in the hope that new investors would continue to bankroll the deception. Both men are now serving long jail sentences.

In the public sector achieving targets is often viewed as a key imperative. The penalties for failing can be severe and not surprisingly most organisations achieve them. However, there are highly publicised cases of such organisations apparently achieving targets but in fact deluding themselves, manipulating their figures, not telling the whole truth or actually lying about their position in order to appear to meet them.

This syndrome is typically triggered by excessive pressure to achieve without the accompanying wherewithal, leading to a frightened or actually dishonest response (or both) by someone in the accountability chain pretending they have achieved something they haven’t. This deception then becomes ingrained and over a period of time others collude and the reality moves further and further from what is being presented. Nick Leeson did it at Barings Bank and many of those fixing LIBOR rates did it too. As the truth has emerged, organisation after organisation has fallen into deep failure. Resignations, public crises, charges of fraud, prosecution, conviction often follow. Morale falls through the floor. And because systems have been misused or set up to create a false picture, processes will not be working properly and delivery will be imperilled.

Objective and reality are turned on their heads so that in this delusional or denying world the objective defines the reality instead of reality defining the objective. We want unreliable and thus high-cost mortgages to be reliable and therefore cheap, so we will put them through an arcane and impenetrable rebranding process and … hey presto! Subprime mortgage lending. We want interest rates to be lower or higher, so in setting LIBOR we will say they are and they will be. Unfortunately the fiction has to come to an end sooner or later, as it did in both cases. And the later, the worse.

Outcome delusion or denial often applies to clinical failures, typically involving patient harm or even death, and can precipitate organisational failure. In the Bristol Royal Infirmary in the mid-1990s heart operations kept being done on children even though the mortality rate was much higher than in other hospitals. The hospital convinced itself that these outcomes – these deaths – were acceptable and defensible, and found explanations and excuses to justify them. It would not listen, and strongly resisted other less favourable explanations. When it finally came to public notice just how bad the outcomes were, how many children had died, and the unacceptability of the practice, it led to one of the most profound organisational changes in the history of the NHS. The effect on Bristol was devastating. It was publicly shamed and on the floor.

Phase 4: Rock bottom

The organisation hits rock bottom very quickly. There is now no concealment that there is no action. The organisation is totally reactive as it has lost all sense of direction. At this point it has moved to phase 4 – stuck on the bottom with low morale.

This is when it is at maximum risk of blame and has minimum ability to defend itself. There is an over-reaction: those who have missed the tell-tale signs now see tell-tale signs everywhere. The organisation, metaphorically unconscious on the floor, is blamed not just for all its own failures but often for many failures which are not its fault. I remember observing in one organisation that it seemed to be blamed for the fact that it had rained yesterday!

At this time people other than management, the board or outside interested parties, if the failure is spectacular enough, start to push the organisation to deliver immediate outputs. They may even provide short-term fixes, but they are external and alien and as soon as the fix is withdrawn, the problem returns – it was never fixed in the first place.

This is my take on what is known in financial circles as the ‘dead cat bounce’ and is shown on the Yosemite curve as a little bump in the flat lining that characterises phase 4. (The rather grisly metaphor refers to what would supposedly happen if a cat were dropped from a Wall Street skyscraper: it would indeed bounce but it would nonetheless be dead.) The organisation is effectively moribund but is being pushed by people remote from it to satisfy short-term imperatives that do nothing to improve real performance. Permanent improvement will only be achieved by fundamentally reviewing and redesigning the underlying systems and, critically, embedding the skills needed to manage the good, new systems in the permanent staff.

Phase 5: Recovery

What can and does improve performance is the introduction of effective new management, bringing with it effective new direction. Improvement takes some time because analysis of and response to immediate problems have to come first. If the new regime isn’t up to solving the problems or doesn’t go about things in the right way, the business will remain at ‘rock bottom’ (phase 4) until it gets a regime that can actually tackle things.

All that said, a competent new regime will start to make a difference relatively quickly. In later chapters I will describe this process and the management skills and tactics needed to bring about the improvement. Performance will, at first slowly, but nonetheless steadily, improve.

Phase 5 can also be dangerous. Performance is now actually better than practically everyone, particularly those judging from outside, think it is. This typically acts as a significant drag factor on the improvement because once again much effort has to go into managing perception rather than reality: in other words, the sceptics have to be shown in unequivocal terms that material, positive changes are taking place and are impacting positively on performance. There are very understandable reasons for scepticism, though they are not necessarily good ones. Those charged with monitoring and scrutinising the business’s performance may be frightened or wary. They were late in seeing how problematic it was and will naturally believe that it is much more dangerous for them to get caught a second time. The result: they tend to underestimate what is going on and react accordingly.

At the Royal United Hospital, Bath, for example, although we had made major improvements, I was told that if I continued to exaggerate them, the Health Authority would publicly dissociate itself from us. It took quite an effort both to continue to demonstrate the improvement publicly and then to show them that any exaggeration was not ours but the media’s. We did, however, manage it, so you can get through this, if you have a good story to tell.

Phase 6: Consolidation

Phase 5 need not be static, but, sadly, it can go on for a long time. The business’s successes are slowly realised but often too little and too late. The best way out of this is a performance epiphany or event, which spectacularly demonstrates to those outside that the world has indeed changed. Once that happens the organisation is back in the normal world: performing reasonably and seen to be performing reasonably – phase 6.

I remember vividly this happening at Medway at a meeting with our senior government monitor. He first, slightly grudgingly, noticed minor improvements in our waiting times, then realised they were very major indeed; then, when we explained how we had achieved them, he realised that we had in fact implemented a pioneering management system. After that he asked us if we would become national exemplars. All this took place in one meeting (a full account of this appears on page 109).

Though Bear Stearns certainly was a failure, JPMorgan picked it up with the aim of putting it back together. The buyer knew what it was doing. It was getting, according to the Financial Times, ‘a prime brokerage business, a large franchise with a promising future’ – and at a bargain-basement price. It judged that the company was remediable and recoverable.

The London Millennium Dome, built by the last UK Labour government, cost about $1 billion but signally failed to meet PM Tony Blair’s aim that it should be ‘a beacon to the world’, and was perceived post-millennium as a classic white elephant. It was eventually sold to Anschutz Entertainment Group at a knock-down price and it has now been successfully redeveloped as a profitable and once more iconic indoor entertainment arena.

To sum up …

There is a clear, predictable pattern to failure, how it happens and what its course is, and the key clue in the pattern is that the perception of performance and the reality of performance move dramatically apart. This is unsustainable and precipitates deep or fundamental failure. The Yosemite curve tracing failure divides into six phases, through the fall, to the bottom and into recovery.

Understand this pattern, understand the phases and what moves you from one phase to the next, and you will have a sound basis for understanding how and why failure happens, how to get out of it and how to avoid it in the first place. In the remainder of the book, I set out the skills and behaviours you will need to do just that.