2 The Mass Privatization Programme

The ideas, their evolution and their embodiment in law

Introduction

Summaries of the Privatization Programme in Russia often make the assumption that there was one well-defined policy; that it was clear; that it had one set of architects; that it was well prescribed in legal terms, as it might have been in an advanced market economy; and that the process of privatization was bimodal, or that one could readily distinguish the characteristics that meant a company was or was not privatized. However, closer analysis of the history of the various different attempts at privatization and quasi-privatization in Russia, of contemporary accounts of events, and of the writings of those advising on privatization reveals that the situation was considerably more ambiguous.

First, there were many versions of privatization and marketization building upon, or even reversing, one another. Few of them followed the prescriptions of any one political grouping, few were even complete, and few created definitively privatized entities. Arguably, this includes companies privatized through the Mass Privatization Programme. Second, there were many architects of different versions of privatization. In part, this was because there were many loci of power: before and after the abandonment of the Soviet Union; executive and legislative; local and national; in enterprises and in ministries. Finally, there is a tendency in the economic literature to distinguish only between private and state-owned enterprises. In fact, private enterprises can often be highly regulated and controlled by the state, whatever their apparent legal ownership. This is certainly true in the advanced market economies, where companies in certain regulated industries are deeply beholden to the state. But it was even truer in Russia, where, as we shall see, the corpus of law to protect private property was neither well defined, nor well established, nor enforceable.

The confusion about privatization law arose, in part, through disputes, both in law and in practice, arising throughout the period 1990–93 when key privatization decisions were made about who had the authority to set the legal framework (Blasi et al. 1997: 19–21). In the period before the collapse of the Soviet Union there were conflicts between its authority and the Russian parliament in a period called “the War of Laws”.1 The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic declared in June 1990 the primacy of its laws over those of the central Soviet authority.2 But even after the breakup of the Union and the establishment of the Russian Federation as its successor state, there were conflicts between the legislature and the executive branch of the Russian government over who had jurisdiction in issuing primary or enabling legislation or in implementing the law (Barnes 2001; Remington 2001: 84–6). Further, particularly in the early days of the new Russian state, there were substantial claims made by the regions about their own authority emerging from the 1992 Federation Treaty, which expanded the shared and residual powers enjoyed by subnational units (Lapidus 1994, 1999; Hanauer 1996; Solnick 1998: 63–6; Graney 2001: 36; Hahn 2003; Chebankova 2008). It is important that the implementation of privatization was not something that was fully controlled from the centre. As one reformer remarked, “the implementation capacity [of the Russian government] was extremely low”.3

Therefore, many forces were involved both in the passage of the key Privatization Programme in June 1992 and in its implementation. This law was a major milestone. It was vitally important in getting a consistent privatization process going, but it was neither the beginning nor the end of that process. We underscore the comments of Frydman et al. (1993: 15), written at the beginning of the implementation process of the MPP:

the legal situation in Russia is complicated by a plethora of often overlapping and conflicting laws and decrees emanating from a number of jurisdictions … as a result the same subjects are often covered by many different and mutually contradictory normative pronouncements, and it is sometimes difficult to ascertain their ultimate validity.

This very confusion was one of the key considerations that led the World Bank and other international organizations to support the 1992 Programme, since it had the support of both the government and the parliament. Here is the view of the World Bank (1992: 69) in its 1991 report on Russia, which was published the following year:

A fundamental difficulty for the conduct of government and the implementation of reform is the current uncertainty about the constitutional base and political future of the new state… . The powers of presidential and government decree are extraordinary. They were designed to fill the inevitable gap in time that would be created by the ordinary legislative process. Therefore decrees are often introduced simultaneously with an identical bill in the legislature and last only so long as the bill does not get passed or defeated in parliament. [This allows] state agencies as well as individuals and corporate entities to speculate about the durability and enforceability of decrees with which they do not wish to comply.

By resolving ambiguities in the primacy of laws, according to the World Bank report, a decisive action would have “a very high premium indeed” (ibid.).

In this chapter, we aim to provide an overview of the dilemmas leading up to the passage of the Privatization Programme in 1992. The chapter contains four main sections covering:

- the history of privatization legislation and a description of who was responsible for the law and its implementation until 1992;

- the ownership status of Russian enterprises prior to 1992;

- the appointment and involvement of the reformers;

- the terms of the 1992 legislation.

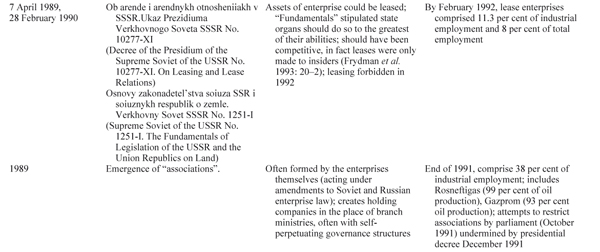

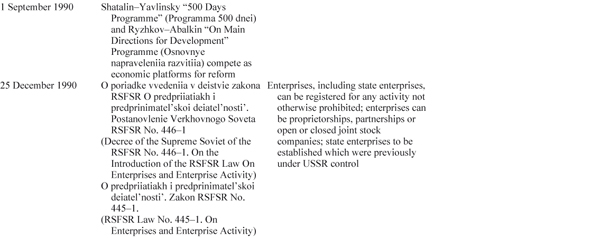

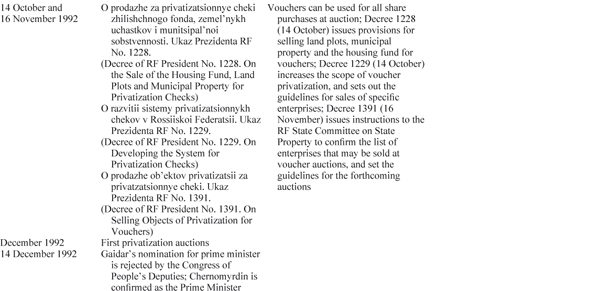

At the end of the chapter, we give a timeline of key events (Table 2.1), noting when various decisions were taken. Throughout the chapter and elsewhere, we refer to the June 1991 Law on Privatization of State and Municipal Enterprises in the Russian Federation as the Privatization Law. The presidential draft of the first Privatization Programme, issued in December 1991, Basic Provisions of the State Programme for Privatization of State and Municipal Enterprises in the Russian Federation, is referred to as the Basic Provisions. A version of this was enacted by parliament in June 1992; we refer to it as the Privatization Programme.

Who was responsible for privatization?

Constitutional considerations

Until 1990, there were 15 Soviet republics; Russia, by far the largest, dominated the affairs of the Union. After 1985, under Gorbachev, the decline of Communist Party control over the country encouraged nationalist mobilization in some republics, culminating in a demand for independence in the Baltics and Georgia and demands for sovereignty in Russia (Dallin and Lapidus 1991: 376; Goldman et al. 1992: 10). In March 1990, the Russian Republic elected a new legislature, the Congress of People’s Deputies, and in May elected its president, Boris Yeltsin, who presided over its working body, the Supreme Soviet. On 12 June, confirmed by various laws in subsequent months, Russian laws were declared supreme over those of the Soviet Union. In June 1991, Yeltsin stood for and won the new post of president of the RSFSR by a landslide vote. At that time there was a proposal, which had been ratified by referendum in many of the republics, to create a more decentralized federal structure, called the Union of Sovereign States.

Its implementation, however, was interrupted by the coup attempt against Gorbachev. Instead, in December 1991 a loose association, which included Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, was formed and became known as the Commonwealth of Independent States. Other republics (excluding the Baltic states) would join later. At that point, the Soviet Union was dissolved (Suraska 1999; Walker 2003). It is remarkable that the breakup of the Soviet Union, and the resulting creation of 15 new nations, was, with the notable exception of the Caucasus, achieved with so little bloodshed.4 In the history of nationhood, it is rare for such events to take place without long and protracted struggle, especially in the context of limited planning for such a breakup. This must surely rank as one of the great political achievements of the time.

However, state formation did not end the confusion about how things were to be done and who had the authority to control them. The Russian legal system still retained the same hierarchical structure as the former Soviet Union: first, the constitution (a document dating to 1977, which had been repeatedly amended), and second, the Fundamentals of Civil Legislation, including laws, ordinances and normative acts, the 1991 edition created by Gorbachev (Angelo 1993: 208). Among sources of confusion, for example, were how inter-regional trade was to be conducted, which government body controlled economic policy and regulated payments and banking, and whether a new currency should be created. Confusion over ownership was particularly acute. Under the former command administrative economy, ownership of the means of production in the late Soviet years was breaking down. Gorbachev’s efforts at management reform resulted in a mix of management discretion and planning in the allocation of resources, and in the rise of cooperatives by the end of the 1980s, which led, for example, to the creation of thousands of new farming entities alongside the still dominant collective and state farms (Berliner 1976, 1988; Åslund 1989; Rutland 1992; Leonard 2011).

This theme of chaotic circumstances, preceding and following the Soviet breakup, is familiar in the literature (Åslund 2002; Sakwa 2002; Walker 2003). One effect was that, in the period leading up to dissolution, there was ambiguity about whether Soviet or Russian law was sovereign. So, for example, as discussed further below, Russia’s 1990 Enterprise Law, passed a year before the breakup of the Soviet Union, “revoke[d] the law of the USSR on enterprises in the USSR, including its application to enterprises under Union control”.5

Within the new Russian state there was also ambiguity about constitutional powers. On 1 November 1991, Yeltsin was granted special executive powers, which validated presidential decrees in the sphere of economic reform unless they were overturned within a week by parliament.6 As tensions grew between the President and parliament, it became more difficult to know whether a presidential decree was likely to be valid for long. This tension is apparent in the writings of Russian reform ministers, such as Chubais and Mostovoi. So, for example, Mostovoi (1999a: 46–7) writes that the decree explaining the major issues of privatization was adopted, a temporary document meant to be in force only until the state privatization programme was accepted by the Supreme Council. On 29 January 1992, another presidential decree was passed that was drafted by his group. The programme itself later encountered difficulties in being approved by the Supreme Soviet, but the 29 January decree is associated with the launch of privatization. It “included major normative documents regulating the order of privatization … [which] … were in force during the whole period of voucher, and partly monetary, privatization until around 1996” (ibid.).

Yet, despite this apparent confidence that the rules for privatization were approved in January, in March of that year the leader of the World Bank Russia Working Group wrote to Chubais that the draft privatization law lacked “a clear description, readily appreciable by both the Russian public and the international investment community, of the processes involved” in privatization.7

In reality, little was done to implement a formal process of privatization until the passage of the Privatization Programme in June 1992. So, while decrees may have represented the policy position of the executive, arguably, it was not until there had been extensive negotiation and compromise to ensure the passage of the programme through parliament that a legal authority could be said to have been established. Further, even when the Privatization Programme was passed, the details of its implementation remained very unclear, potentially allowing a level of discretion that could have negated its apparent intent.8

Just as legal ambiguities could be used to prevent privatization, they could also be used to accelerate it, if those who had the de facto power chose to do so. Mostovoi notes that a diversity of plans for privatization were in effect at the same time, as allowed by the 1989 “resolution”. This is because the 1989 resolution covered a process that was broader than just privatization, that is, de-statization, which could comprise many ways of reallocating state property:

So, there was a law on privatisation and, simultaneously, a law on leasing was being developed… . According to this law, a state enterprise could also be leased. These two laws were being developed simultaneously and contradicted each other, as one law didn’t take into account leases, while the other one didn’t consider sales – unless it was under special circumstances. And, as such, it was assumed that whoever decided to lease an enterprise would eventually be able to purchase it.9

Another example is the exclusion of Moscow from the country-wide Privatization Programme, blocking the government’s oversight by exempting Moscow in a special decree. Chubais objected, claiming that “shops were given to staff at residual value … such a scheme was in crying contradiction of the law on privatization” (1999b: 153). He goes on, more forcefully, “Piyasheva and Pinsker [advocates of Moscow’s privatization] prepared and pushed through ‘their’ decree of the President, after which an unimaginable orgy started” (ibid.: 155).

So, by the time of the passage of the 1992 Privatization Programme, although there was considerable support for the notion of privatization, there was still disagreement regarding the form that the privatization could take. Meanwhile, by using Soviet-era resolutions and laws, such as those discussed in the Introduction above, many privatizations had already taken place, for example through leasing.

The 1992 Programme was therefore not the first attempt at designing a method for privatization. Rather, its aim was to build on earlier legislation to establish a unified legal code embracing proper title to productive assets. That in turn required that it have clear political authority and support.

Institutional considerations

In addition to these legal wrangles, there were also different responsibilities assigned to different institutions involved in setting up and carrying out the privatization. The agency with overall responsibility for the implementation of privatization was the State Committee for the Management of State Property, or Goskomimushchestvo (GKI), founded in November 1990, of which Chubais became head in November 1991. It in turn depended on local GKIs to implement privatization. The GKI was responsible to the president. But the seller of the assets was the State Property Fund, and/or its local representatives, which reported to the legislature. In addition, in larger enterprises, it was a self-appointed “privatization commission” that drew up the privatization plan for an individual enterprise. Each oblast (region) also had its own property committee charged with small enterprise privatization.

There were good reasons for this division of powers. For example, the split between the state or local Property Funds as the owner and the GKI as responsible for the sale gave some protection against corruption. The use of privatization commissions reduced administrative burdens on the GKI and accelerated the process. However, the opportunity for confusion and argument in the process remained considerable. Frydman et al. (1993: 44) observe:

in addition to the State Property Committee, its territorial agencies, the local property committees, and the privatisation commissions, a number of other state organisations are involved in the privatisation process. It is sometimes difficult to specify their involvement with precision, since Russian laws and decrees often remain without effect or contradict one another.

One effect of this was that the progress of privatization and its conduct were different in different parts of the country. So, in some areas, privatization may have progressed according to the norms and expectations of the lawmakers and GKI in Moscow. Elsewhere, the situation was very different, as illustrated in the descriptions of the process in Novosibirsk and Smolensk given in the Appendices to this book. In one extreme example, a foreign adviser to the GKI was sent to observe the process of privatization taking place in a particular city. He was turned back at the airport, and told that his life would be in danger should he decide to return.10 One can but speculate how the process was conducted in that city.

The key point is that neither the central policy makers, nor the GKI and the reformers, should be assumed to have been in full control of what was taking place. Ellerman (2003: 15) has described the reformers as “market Bolsheviks”, in the sense that they were a small ideologically driven group, intent on delivering their own prescription for Russia’s problems. Rather, they might be described as a group who had limited command of the levers of power. As one of the reformers puts it:

The government did not control anything … I always had the sense that we were pressed, pushed, kicked, hit from all directions. And you needed to think very hard about what is crucial and essential and what you can give away.11

Indeed, the reformers themselves accept that their powers to implement and enforce the law were limited. Reflecting on the Moscow privatization, which was legal by exception, Chubais (1999a: 79) reflects:

Of course, I could concentrate all my political resources (not very considerable) to achieve the rejection of the presidential decree [on the privatization of Moscow by its own method] by introducing an amendment, or start a propagandistic campaign against the Moscow programme. But I made a decision not to touch it. In pragmatic terms it was more reasonable to concentrate energy not on the wrongheaded privatization [in one region] but its absence [i.e. the right privatization] in other regions.

Thus, in considering how privatization took place, it is important not to exaggerate the degree to which the government in Moscow was united or in control of the process.

The ownership of Russian enterprises prior to the 1992 Privatization Programme

There is a tendency to think of Russia in 1991–92 as having the same economic control structures as the ones employed in the Soviet Union five years earlier, and that it was onto these structures that the Privatization Programme was superimposed. But the situation was much more confused than that suggests. As outlined in the Introduction, ambiguities arose from the fact that both the Soviet and the Russian authorities had been passing laws and decrees that both went into the code of laws, creating different forms of “private” ownership.

The enterprise acts of the late 1980s, issued both by the Soviet Union and by the Russian Republic, had allowed enterprises a degree of discretion to sell their own output. They had also allowed the establishment of new companies. For example, in 1989 and 1990, managers had been encouraged to lease the assets of the enterprise that they managed, in effect privatizing its operations without privatizing its assets. So, according to Frydman et al. (1993: 22), in February 1992, before the 1992 Privatization Programme was passed, 13 per cent of total production and 11 per cent of industrial employees could already be categorized as part of enterprises which were “leased”. This represented approximately a two-fold increase over the previous year.

A similar observation applies to the emergence of industrial “associations”. The RSFSR Enterprise Law, signed by Yeltsin on 25 December 1990, set out that each enterprise should be established as “an independent economic unit”, which would “independently pursue its activity and dispose of its output and profit”.12 It further required that state enterprises be set up, but while “the assets [were to] be the property of the RSFSR”, the “assets [could] be transferred to the management of the labour collective of the enterprise”.13 Further, enterprises could form unions and associations. Despite the fact that Russia was then still part of the Soviet Union, as noted above, the law went on to revoke “the law of the USSR on enterprises in the USSR, including its application to enterprises under Union control”.14

One response to this, and possibly other, legislation was the creation of “associations”, which often took corporate form and frequently took the role previously assumed by the branch ministries, which would have organized the details of industrial production. Thus, the “associations” created a vast vertical of non-governmental agencies with potentially huge influence. In 1991, they accounted for 38 per cent of industrial output, including the entire oil and gas industry, the coal industry and Norilsk Nickel. In late 1991, the Russian parliament resolved to restrict the powers of the “associations”, so that they were “not authorised to represent the state in the disposition and management of state owned property, and could not conclude contracts with the leaders of constituent state enterprises” (Frydman et al. 1993: 25). But, in December 1991, a presidential decree restored some of these powers. We will return to the issue of “associations”, and the challenge they presented to the privatization process, later in the book.

The effect of these “privatizing” laws is illustrated by Johnson and Kroll’s (1991) study of enterprises in Kiev, undertaken just before the breakup of the Soviet Union. They report a vibrant response by enterprises to the collapse of central authority, using the new powers conferred by recent enterprise laws. These included both centralizing and decentralizing tendencies. They observe that “managers clearly felt that if something did not technically violate the rules and they could get away with it, then they would go ahead” (ibid.: 301). Given the contradictory nature of the law, this would give ample scope to new structures. While this study was undertaken mainly in Ukraine, there is little reason to believe the situation was very different in Russia.

The World Bank’s view, in a private note to Chubais in March 1992, was that “the ultimate goal [of privatization was] to create effective ownership of Russia’s productive assets”.15 In 1992, this meant not only setting a framework for the development of a successful market economy, but also establishing a clear framework property rights that had become obscured by the chaos of the previous years.

The appointment and involvement of the reformers

The privatization reforms are generally attributed to the reform ministers, in particular to Yegor Gaidar,16 who became acting prime minister in 1992, and Anatoly Chubais, the minister in charge of the GKI and, subsequently, a deputy prime minister. However, we note that Gaidar and Chubais were appointed in November 1991, after the passage of the 1991 privatization law. They only had a matter of weeks to work on the “Basic Provisions” that constituted the government’s proposals for reform.17 Though both were respected economists, neither of them had had much previous experience of high office.18 Nor were they allowed carte blanche in designing their reform.

Gaidar was appointed as head of the reform team on the recommendation of Gennady Burbulis, Yeltsin’s state secretary (July 1991–May 1992). Burbulis himself was appointed by Yeltsin to “share the total responsibility for running the country … [including] long term planning and selection … [of] personnel, leaving [Yeltsin] free to conceive the … tactics and the strategy of the immediate political struggle” (Yeltsin 1994: 151). According to Yeltsin (ibid.: 156), the reformers thought of themselves primarily as technocrats, engineers who would design an economic reform independent of the political processes necessary for reform to be effective:

Gaidar’s ministers and Gaidar himself took this position with us: your business is political leadership; ours is economics. Don’t interfere with us as we do our work, and we won’t butt in on your exalted councils … which we don’t understand anyway.

Yeltsin presumably accepted this position. However, the consequences of the failure more effectively to link economic policy with its likely consequences were soon evident. He notes (ibid.: 158): “Soon it became apparent that the Gaidar government, which was making one decision after another, was in complete isolation. Gaidar and his people never travelled around the country to take the pulse of the nation.”

In 1992, the World Bank Consortium commissioned Oxford Analytica (OA), a leading geo-political consultancy,19 to draft a report on the political backdrop to effective privatization in Russia.20 The OA report provides a snapshot of the politics of Russia in August 1992. This is their assessment of the position of the reformers within the government:

The Gaidar reform team, including senior advisors with the status of first deputy ministers, consists of about 30 people. They do not constitute a dominant element in the government; they do not represent a political party; they have no significant power base in Russian society. They are in government because Yeltsin’s close advisor, Gennadii Burbulis, recommended Gaidar as head of a reform team, and Gaidar brought in a group of like minded friends.21

Of course there were no political parties in the Soviet system other than the Communist Party. The OA report goes on to observe the chaotic conditions of political decision-making within the government:

A lack of orderliness and of generally accepted rules of the game characterises almost all social activity in Russia today. This is as true of the running of the Russian government as it is of other activities. Western observers in Moscow agree that all officials, with a few exceptions [including Gaidar and Chubais], are very disorganised and that the situation is not improving.22

Gaidar, in his autobiography (1999: 97–8), confirms that many in this liberal group were newcomers to government. Talking of his appointment as deputy head of the government (6 November 1991) and minister of economy and finance (13 November 1991), he wryly notes that he had never held a government post or supervised more than his own desk (ibid.: 97). He goes on to say that “there were only two people [in the government] who combined a genuine administrative savvy with profound understanding of the essence of transformations in their relative fields”: Chubais and Bulgak, the Minister of Communications (ibid.: 98).

Some political difficulties resulted from inexperience, but mainly they reflected the failure of the political process to establish consensus and clearly to delineate spheres of command. This is true even within the executive, where the Vice-President, Alexander Rutskoi, could simultaneously have oversight of agricultural reform, criticize publicly Gaidar’s strategy on liberalization and stabilization, operate as leader of a political party of sorts, and bring that party into an alliance with the industrialists’ party and others.

Ruslan Khasbulatov,23 the chair of the Supreme Soviet and, ultimately, one of Yeltsin’s main opponents, described the relations between the executive and the legislature in an interview for this book: “I told Gaidar and the ministers ‘If you are reformers, give me the laws and I will pass them in three days’”. But he claims they did not give him legislation, and he felt the executive should have taken the lead. He saw parliament’s role expanding in response: “If the government can’t do it, let [the legislature] come up with, coordinate and create laws. And we did make most of the laws, about 90 per cent on our own.”24

The reformers were limited in their powers, according to the law granting Yeltsin authority to “rule by decree” in the economic sphere of policy. They were also constrained under difficult circumstances to keep Yeltsin’s support. This resulted in compromises, in particular with the industrial lobby, whose interests were well represented both in the government and the parliament (Kubicek 1996: 36–7; Appel 1997: 1436; Barnes 1998: 844).

In this environment, as OA observed in 1992, Yeltsin’s support for the reformers, though not unreserved, was particularly significant:

the government rests (insecurely) on Yeltsin’s personal prestige: there is public competition within the government for influence over Yeltsin… . Yeltsin’s own stance is crucial. So far, he has backed the reformers, at a cost to his own personal popularity. The reformers do not take a continuation of this support for granted. From April onward they have given ground to the industrialists … the main achievement of G7 support was to keep Yeltsin on the side of the reformers.

Yeltsin sat at the centre of the debate as it grew more intense. In his memoirs (1994: 176), he noted that by late summer of 1992 the rancour between reformers and others had “stopped the government from functioning normally … there was a coalition government, which in our politically charged atmosphere would be explosive, and frankly, deadly”.

This raises the obvious question of why Yeltsin backed the reformers, and why they were successful in pushing through the privatization reform.

Yeltsin himself identified his own reservations. Enterprise management was not improving, and there were already a confusing variety of schemes for “de-statization”, many of which were of doubtful legitimacy (Blasi et al. 1997; Buck et al. 1998; Puffer and McCarthy 2003). Yeltsin (1994: 156) quotes Gaidar to suggest why it went forward anyway:

I myself could have given a perfect explanation of why, in 1992, the reforms should not have been launched … no stable support in parliament … no normal functioning institutions of governance … sixteen central banks… . But … we couldn’t wait any longer. We couldn’t just keep doing nothing, or keep explaining why it was impossible to do anything.

His point is simply that, particularly in situations of political chaos, the decision to do nothing has equally profound, and often less predictable, consequences than taking action. In the breakup of the Soviet Union, communism had been abandoned and a civil war averted. Yeltsin may have seen the reforms not just as a way to create an effective Russian economy, but as the only credible agenda that his government had the power to implement.

The reformers themselves went much further. Chubais underscored the urgency of preventing a return of communism (Desai 2006).25 And, indeed, the reformers were most successful in two areas: price liberalization and privatization. Price liberalization was introduced in the face of fears of lack of supply, including food supply. It was a partial reform, and one that involved the withdrawal of state power. In other words, having passed the legislation, the government felt it had little else to do to ensure its implementation.26 Privatization required more positive action by government, since a privatization process needed to be undertaken. Both reforms created very powerful incentives for enterprises to comply. In other areas, such as macroeconomic stabilization, bankruptcy and securities legislation, reform was to make much slower progress.

In their style of work and their descriptions of their task, reformers often seemed to see themselves as a close team, working frenetically to secure their goals and to pass and bypass other government departments and the legislature. For example, Mostovoi claimed that at the turn of 1991–92, “We worked a lot then. Usually night and day. Those capable of it worked 24 hours” (Mostovoi 1999a: 69). Chubais (1999a: 33) said of the same period, “It was our good fortune that, at the end of 1991, the government apparatus was extremely weak … it was easier to deal with than it would be a year later”.27 It may be informative that in pushing through de jure plans, Chubais perceived the weakness of the apparatus of government as an advantage. That same weakness would later be given as the reason for the inability to implement a more comprehensive set of reforms.

There can be little doubt of the huge effort and single-mindedness that the reformers put into advancing privatization. However, as the reformers’ comments suggest, they were not in full control of the process they were managing. Even if there had been broader political consensus and a capacity to implement, the economic circumstances into which privatization was introduced were challenging in the extreme. World Bank figures show that GNP fell by 12.8 per cent in 1991, and then by a further 18.5 per cent in 1992 (Blasi et al. 1997: 190). Inflation, which had been at 138 per cent in 1991, looked out of control in 1992 at 2,323 per cent, wiping out whatever value savings had. The IMF estimated that real wages halved during that year (ibid.). It was against this backdrop that action was taken. Gaidar successfully implemented major, though not comprehensive, price liberalization in January 1992; however, by the summer, with the appointment of a new chairman of the Central Bank (Viktor Gerashchenko), he had begun to lose control of one of the levers of macroeconomic stabilization (Granville 1993; Treisman 1998: 243; Weisskopf 1998: 177).

The one reform that did gain traction was privatization. The Privatization Programme depended on more than the commitment and hard work of the reformers. It was facilitated by the fact that the industrial lobby did not oppose, in principle, the notion that enterprises should be privatized. As OA noted in 1992, “the ‘industrialists’ [were] not opponents of privatisation as such. In fact they [were] carrying out their own privatisation already … they [sought] controlling interests in existing state enterprises”.

So, for example, the Civic Union, a grouping of powerful “industrialist-friendly” parties, supported privatization in principle, albeit on its own terms. The same could be said of Khasbulatov.28 Indeed, securing the support of parliament for their privatization plan was a critical element, and one of the great achievements, of the programme’s designers. But while it was undoubtedly a considerable achievement for the reformers to secure the passage of the 1992 Privatization Programme, the law itself was one that reflected the views of other parties. It was not the reformers’ blueprint.

In particular, there was great debate about those aspects of privatization that determined future ownership and control. The 1991 privatization law made the assumption that workers and managers would be given privileges to subscribe for 30 per cent of the share capital of the company at a discount. However, these shares would be non-voting. The programme, when it emerged, had two other “variants”, the second of which allowed insiders to subscribe for 51 per cent of the company in voting shares. It was this variant which was to be chosen by most of the companies privatizing under the MPP (see below).

However, by the summer of 1992, as the privatization law was being passed, other elements of Gaidar’s reform programme were being undermined. Gerashchenko, the new chairman of Russia’s Central Bank, which by this time had come under the control of the parliament, had distanced himself from Gaidar’s stabilization policy. In December of that year, as the first voucher auctions were taking place, Gaidar was replaced as acting prime minister by Victor Chernomyrdin, a representative of the industrial lobby, who was to be head of the Council of Ministers then prime minister until 1996. Before his appointment, Chernomyrdin had made strong statements opposing the Privatization Programme as it stood at the end of 1992. It was under his government, not that of the reformers, however, that most of the controversial aspects of privatization were implemented.

Therefore the period during which advocates of radical reform controlled the reform process lasted only a short time. It involved partial price liberalization, but little subsequent control of credit. Therefore, whether or not price shock was the right solution for Russia, it was certainly not consistently applied (Åslund and Layard 1993; Åslund 1994, 1997). The only major reform from that period that progressed beyond 1992 was privatization, which had parliamentary support. Nevertheless, whoever is deemed responsible for the contents of the Privatization Programme, it was to be the basis of policy implementation for the next two years. It was under this programme that companies employing 20 million workers were sold.

The Privatization Programme of June 1992

The Privatization Programme,29 built on the earlier law of 1991,30 focused on the “supply side” of privatization, establishing three things. First, it set out different categories of enterprises, detailing how and whether they should be privatized. Second, it described ownership choices available to enterprises in the MPP. Third, the programme detailed how other aspects of privatization would be affected, who would have the authority to carry them out, and how the proceeds of privatization would be distributed (see Appendix 1).

It is worth reviewing each of these.

Categories of enterprise

Three categories of enterprises were to be included in the programme.

The first category included small enterprises, employing less than 200 people. These were to be sold through auctions and tenders by the municipality in which they were based. The second included large enterprises, with the number of employees ranging between 1,000 and 10,000. These were to be converted to companies (corporatization), and their managers and workers would then submit a privatization plan to the GKI. Shares would then be sold through one of the privatization options described below, with auctions for cash or vouchers organized by the GKI.31

The third category comprised very large companies with over 10,000 employees and/or strategic enterprises, such as defence and drug companies, and those with monopoly positions. Their privatization required special agreement with the government or the relevant ministry. The GKI would prepare the plan for their privatization.

Critically, enterprises involved in minerals and pipelines were excluded from privatization. This is significant, as much of the criticism of the privatization programmes centred on the legitimacy and the business practices of those involved in oil and other natural resource companies. These were not privatized through a bottom-up process, as prescribed by the MPP, but through top-down approval from the relevant ministry.

The privatization law prescribed three options, each offering benefits to employees and managers of the enterprise.

- Option One allowed employees a free gift of 25 per cent of the equity of the company, up to a face value of 20 times the minimum monthly wage. Initially, it was proposed that these be non-voting shares (though this was not specified in the programme; and in the summer of 1992, the GKI contemplated mandating that shares be non-voting until at least 50 per cent of the enterprise was private). Employees could also buy an additional 10 per cent of the shares at a discounted price, with three years to pay. The total amount of shares purchased in this way could not exceed six minimum wage monthly salaries. In addition, officers of the enterprise could buy a further 5 per cent of the shares. These grants to workers were proposed in the Basic Provisions.

- Option Two prescribed an even greater distribution of shares to employees and other insiders. Fifty-one per cent of shares could be purchased, with the GKI setting the price. The GKI ultimately decided that that figure should have been 1.7 times the book value in July 1992. Thus, Option Two allowed employees and managers to take control of their enterprise, which was arguably the closest reflection of the situation in most enterprises before the passage of the law and, as we have noted, was supported by the industrialists’ lobby.

- Option Three allowed the purchase of 40 per cent of the equity of an enterprise by a smaller group of insiders willing to restructure the enterprise. This option was seldom adopted.

In addition to all the advantages prescribed by the different options, the Programme allowed enterprises to establish “personal privatization accounts”, which were set up to receive 10 per cent of the proceeds of any sale of shares to outside investors. The development of these three options reflected the debate between the industrial lobby, which promoted insider control and therefore a legitimization of the status quo, and the reformers, who felt that outsiders would be required to promote the strong governance necessary to restructure Russian industry. This was well understood at the time by reformers and by observers: “As evidenced by some of their public comments, the authors of the state programme were clearly aware that the modifications introduced since the privatisation law were largely a victory for enterprise insiders and the industrial lobby” (Frydman et al. 1993: 57–8).

Other aspects

One critical element of the Privatization Programme was its bottom-up structure. That is, for all but the largest companies, the form of privatization was developed by the management of the enterprise and then approved by the GKI. This led to a significant transfer of power to insiders. The bottom-up approach had been strongly recommended to the GKI by the World Bank, largely on technical grounds. In a private draft note to Chubais on 25 March 1992, the World Bank Group on Mass Privatisation wrote:

Recent experience in other countries suggests that, if such a top down structure is adopted (i) it would require the GKI to have substantial administrative organisation before the privatisation process … can begin (ii) the privatisation commissions will be susceptible to paralysis and delay and (iii) the burden of expert and affirmative obligations … is likely to be unsustainable, resulting in general institutional “meltdown”.

It went on to recommend the bottom-up approach, saying:

This approach recognises two related truths of fundamental importance: management is the one group which already has the necessary expertise to quickly move the privatisation process forward and management is also the one group that, if alienated or made defensive by outside pressures, is best positioned to cause obstruction and delay.32

Therefore, the Privatization Programme, passed in June 1992, was not a charter for radical reform. Indeed, it can be argued that the 1992 Programme was rather less radical in some ways than the 1991 law, which was passed before any of the key reformers were appointed to office and before any of the western advisers on privatization arrived. The 1992 Programme had been amended, both by intention and by necessity, to satisfy the demands of those in charge of the enterprises that were to be privatized. It is therefore perplexing that some writers criticize the reform and the reformers in colourful language for achieving the opposite. For example, David Ellerman (1998: 15), speech writer to Joseph Stiglitz, writes:

To promote market driven development, reforms should find some way to formalise some socially acceptable approximation to … de facto property rights … instead the market Bolsheviks [the reformers] designed the market reforms with the exact opposite purpose to deny the de facto property rights accumulated during the communist past … the reforms were successful in denying the de facto property rights acquired during the earlier decentralising reforms.

In fact, the reverse was the case. Whatever the rhetoric of the reformers, the reality of the MPP was likely to leave control of enterprises in the same hands as before. The de facto property rights of managers and workers were upheld.

Indeed, had enterprise managers or their workers’ collectives decided to subvert the law, it would not have been difficult for them to do so, albeit at the cost of losing their privileges to receive shares in the enterprise at a reduced cost. They could have claimed to be exceptions, for example by asserting that they had dominant market positions. Alternatively, they could simply refuse to cooperate, failing to set up privatization commissions or submit plans.

The time frame for the programme was ambitious. Enterprises were to submit privatization plans by 1 October 1992, with enterprises becoming companies on 1 November. Share auctions were to take place shortly thereafter.

In its initial conception, the proceeds from those auctions were to be split between the federal and regional governments. For large companies subject to mass privatization, 35 per cent was to be credited to the federal budget, 10 per cent to municipal budgets, and 45 per cent to the regional budget. It was the intention of the federal government that its share of the proceeds of privatization would be distributed to the Russian population by way of privatization vouchers. However, the nature of the “vouchers” or “privatization accounts” had not been made explicit.

Vouchers

From the perspective of internal Russian politics, one of the most controversial aspects of the privatization was the way in which vouchers were issued. In April 1992, Presidential Decree 322 declared that vouchers would be distributed to the whole population in the last quarter of the year. The outline of how the vouchers would work was described in a further decree in August, at a time when the Duma was in recess.33 Critically, vouchers were to be tradable instruments; that is, they could be sold.

However, according to Khasbulatov, then the Speaker of the Duma, the notion of issuing vouchers as tradable instruments had not been the intention of the original 1991 law or the 1992 Programme. Here is his description of the situation:

We [the Duma] approved all the [privatization] programmes. [But] after the law was approved – the law that was proposed by Yeltsin’s government – after it had been enacted, they made arbitrary changes to that law … I think in England you would go to jail for that!

I’m talking about these privatization vouchers. Chubais’s vouchers. When we ratified the law, we designed [the vouchers] to be registered. I would be given vouchers with my name marked on them [that could not be sold]. What did [the government] do? They released these privatization vouchers… . And thousands of people – opportunists, swindlers – began to buy up these vouchers.34

The reformers recognized the change, if not its legal ambiguity. Gaidar (1999: 169) said that initially the legislation on privatization did not provide for any currency-like medium: “We had proposed creating a system of registered privatisation accounts … [but the time and expense of doing so would] deprive the country of a window of opportunity.”

The supply of companies to be privatized was agreed to by the executive and by parliament. However, the nature of vouchers – in particular, their tradability – was contested.

The idea of voucher privatization was to ensure that those citizens who were not workers in industrial enterprises – teachers, pensioners, doctors – received some benefit from the process. Kikeri et al. (1992) underscore that the overriding purpose of privatization was to transfer the property rights of owners who have incentives for defending the interests of the capital they own. Private owners would provide political support for the difficult steps in creating a market economy. At the time of the passage of the Privatization Programme, an assumption was made that shares would be sold for cash and for vouchers. These vouchers were to be distributed to Russian citizens, and could be used either as part payment in worker subscriptions or at auction, in part payment for the 35 per cent of the privatization revenues that would otherwise have gone to the federal government. The vouchers played a critical role in the justification of the process.

However, the mixture of cash and vouchers created technical complexities in ensuring that the supply of companies could be readily matched with subscriptions. For example, if vouchers were to be exchanged for shares, either at book value (as would be the case for worker subscriptions) or at an auction in place of cash, they needed to have a nominal value. If there was then a difference between the nominal value and the value of shares for which they subscribed, the proceeds of privatization represented by vouchers would be different from the 35 per cent that was due to the federal government. This problem was only resolved by extending the voucher programme to cover all sales of shares. This, in effect, meant that there was to be no money raised for any state entity through the MPP. In one stroke, one of the key objectives of privatization, that of raising money for the state, was abandoned.

Vouchers also affected the timing of the programme. Vouchers were intended as temporary instruments with an expiry date. Initially, this was to be the end of 1993. Thereafter, it might be envisaged that a second privatization programme would be launched, and a new set of vouchers issued. In fact, only one tranche of vouchers was ever issued, with their expiry date extended to 30 June 1994. Therefore, the MPP had come to an end by that date. This created huge pressure for a speedy process before vouchers expired.

The voucher programme also created considerable logistical challenges since the issuance of vouchers and the purchase of company shares needed to dovetail. Further, in the summer of 1992, the GKI had not secured the authority to control the privatization process beyond 1 November of that year, when privatization plans were to be submitted.

However, the combination of vouchers with the incentives given to workers and managers meant that there was significant pressure to move forward with privatization. From the central government’s point of view, once citizens had been issued vouchers, it was necessary to ensure that there was something for them to buy. And the terms of sale for companies, as well as the use of vouchers as currency, meant that those in charge of companies were willing to put them up for sale. Most of them found ways of selling to insiders.

Discussion

The 1992 Russian Mass Privatization Programme was developed and implemented in a period of considerable turmoil. It was introduced during a time when existing laws were contradictory and legal authority was unclear. Enterprises had thus established many forms of quasi-privatization, necessary for effective functioning and encouraged by the self-interest of those in power.

The 1992 Programme built on the 1991 law, which was ratified before any of the Russian reformers were appointed to the government. This is sometimes forgotten in their writings. For example, Boycko et al. (1995: 1) begin their book Privatising Russia by saying: “In late 1991 a handful of reformers led by Anatoly Chubais embarked on a far reaching program to privatise Russian firms. At the time the idea of privatising Russia seemed to most people to be a pipe dream.”

While not wishing to minimize the accomplishments of the reformers, the aim of privatization predated their appointment. The 1992 Privatization Programme, and its associated decrees, gave considerably greater influence to enterprise insiders. It introduced Option Two, which allowed the purchase of 51 per cent of the shares of an enterprise by its workers. The law and the decrees created a bottom-up privatization, in essence handing the drafting of the privatization plans to the enterprise managers. Vouchers allowed workers to finance their subscription for shares.

Some of these changes, such as bottom-up privatization, were accepted and indeed were supported by the reformers. However, at face value, the importance of the 1992 Programme was not that it provided a new blueprint for reform; if anything, it compromised to meet the demands of the industrial lobby. Rather, it provided a set of clear steps and incentives that encouraged those in control to accept a change of sorts. With extraordinary zeal, reformers pressed forward with the programme.

The Privatization Programme alone could not fulfil all, or indeed very many, of the stated aims of reform. It did not produce a hard budget constraint on companies. It did not raise cash for the government. It did not create a governance framework that was likely to make new owners enthusiastic about restructuring. It did not establish the legal framework necessary for the functioning of capital markets, for example a bankruptcy law. It did not create competition or address the problem of arbitrary taxation.

However, it did create the possibility of a framework, most of which was agreed to by the feuding parliament and President, for the transfer in law of the rights over enterprises that were already becoming controlled by enterprise managers, individually and in coalition, together with their workforce. It also offered, controversially, through a tradable voucher programme, some modest transfer of benefits to those not employed in privatized enterprises. However, like so many Russian laws, the Privatization Programme raised many questions regarding its implementation and its likely economic effects, which were understood at the time.35 Some of these were administrative, such as establishing timetables, while others raised questions regarding the feasibility of the programme; for example, that the lack of individual savings would mean that only the well financed (of whom there would be few in Russia) would have funds to make successful bids at cash auctions, or that the programme would allow the creation of vast holding companies. Still others point out the limitation of privatization in the absence of other regulations and institutions necessary for the effective working of capital and labour markets. The passage of the law in 1992 was therefore only the beginning of the process. Its subsequent implementation would be crucial, as would be the decisions made about those enterprises not covered by the 1992 Programme. Certainly, while the MPP gave the opportunity to establish ownership rights, which in turn was likely to be a necessary condition for an effective economy, it was certainly not, at least in the medium term, a sufficient one.

Notes

a See World Bank Development Indicators, GDP growth (annual percentage), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?page=4, accessed 26 September 2012.

b See Blasi et al. (1997: 190).

c World Bank Development Indicators, GDP growth (annual percentage), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?page=3, accessed 26 September 2012.

d See Blasi et al. (1997).