Chapter 6

Sourcing

![]() LEARNING OBJECTIVES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define sourcing and explain the differences between purchasing, strategic sourcing, and supply management.

- Explain the impact of the sourcing function on the organization and the supply chain.

- Describe the sourcing process.

- Explain characteristics of different types of sourcing engagements.

- Explain how to measure sourcing performance.

![]() Chapter Outline

Chapter Outline

- What Is Sourcing?

Purchasing, Sourcing, and Supply Management

Evolution of the Sourcing Function Commercial Versus Consumer Sourcing

Impact on the Organization and the Supply Chain

- The Sourcing Function

The Sourcing Process

Cost Versus Price

Bidding or Negotiation?

- Sourcing And SCM

Functional Versus Innovative Products Single Versus Multiple Sourcing

Domestic Versus Global Sourcing Outsourcing

Electronic Auctions (E-Auctions)

- Measuring Sourcing Performance

- Chapter Highlights

- Key Terms

- Discussion Questions

- Problems

- Class Exercise: Toyota

- Case Study: Snedeker Global Cruises

In early 2010 all major headlines clamored over the news that Toyota was recalling more than eight million vehicles in the United States, Europe, and China for problems with sticking accelerator pedals. Production in the United States had been suspended for eight car models, including the Camry, America's top-selling car, and sales at most Toyota dealers had come to a screeching halt. For a company known for zero defects, this was devastating. Toyota Motor Corporation had been the icon of the quality movement and considered a leader in the automotive industry. Toyota placed blame on one of its suppliers, a company that manufactures accelerator pedals. Given the close relationship Toyota has with its suppliers, how could such a major fault get past them?

Supplying to Toyota is highly coveted among car-parts suppliers and Toyota is known for making it difficult for suppliers to get contracts. Suppliers that are selected are typically monitored very carefully and are rewarded with loyalty. Toyota is known for playing a large role in engineering the parts made by outside firms. Suppliers make parts to Toyota's exact specifications, but are often not involved in product testing. Between the years of 2000 and 2008 Toyota doubled its sales, and the ability to maintain quality during such rapid growth was challenging. To keep up with costs the company demanded that suppliers make parts more cheaply. An executive at a major U.S. supplier said that Toyota had insisted his firm make each generation of parts 10% cheaper. Rapid growth in such a competitive industry may have shown up in the quality of Toyota's cars.

The close relationship between supplier and buyer, as seen between Toyota and its suppliers, makes it difficult to identify the true source of quality problem when they occur. The fault could be with the supplier in manufacturing the part, or with the component parts the supplier sources from their own supplier. The latter situation occurred a few years earlier when the toy manufacturer Mattel had to recall toys due to the use of lead paint by its supplier's supplier in China. Another source of the quality problem could be the specifications defined by the manufacturer. Yet another could be the treatment that supplier parts may go through after receipt by the manufacturer.

Although the close relationship between supplier and buyer is necessary to achieve rapid response in today's competitive marketplace, it illustrates the importance and complexity of the sourcing function. Purchasing parts is not merely about lowest price. It is about building lasting long-term relationships and helping each other through challenging times.

WHAT IS SOURCING?

PURCHASING, SOURCING, AND SUPPLY MANAGEMENT

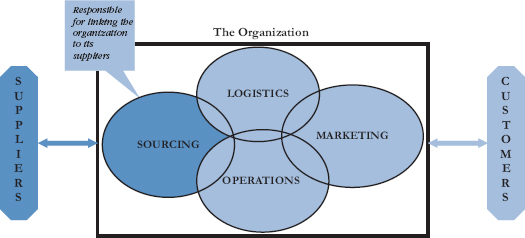

Sourcing is the business function responsible for all activities and processes required to purchase goods and services from suppliers. Every organization has customers and suppliers. The sourcing function has primary responsibility for the supply side of the organization, whereas marketing has primary responsibility for the customer side of the organization. We can also say that sourcing addresses the “upstream” part of the supply chain. Figure 6.1 highlights the functional position of sourcing within the organizational framework.

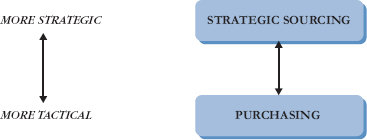

The sourcing function is often referred to by a number of different terms and there is some confusion regarding its name. These names include “purchasing,” “procurement,” “sourcing,” “strategic sourcing,” and “supply management.” Although they are often used interchangeably they do not necessarily mean the same thing. In this text we use the term “sourcing” to refer to the overall management of the supplier base, encompassing all the terms and the range of activities, from tactical to strategic. However, let us clarify the differences in these terms.

Purchasing is a term that defines the process of buying goods and services. It is a narrow functional activity with duties that include supplier identification and selection, buying, negotiating contracts, and measuring supplier performance. The term “purchasing” is also frequently used as the title of the business function within organizations.

Over the years the purchasing function has evolved to include a much broader and more strategic responsibility, which is termed “strategic sourcing” or “supply management.” Strategic sourcing is not the same as purchasing and involves a much more progressive approach to the sourcing function. Strategic sourcing goes beyond focusing on just the price of goods to looking at the sourcing function from a strategic and future oriented perspective. It considers sourcing opportunities that will solve greater problems for the buying firm and give it a competitive advantage. This requires expanding the role of sourcing from mere buying, to building close and longer term working relationships with specially selected suppliers and partners. Therefore, it is important to remember that purchasing and strategic sourcing are not the same, as illustrated in Figure 6.2.

FIGURE 6.1 The sourcing function.

FIGURE 6.2 Hierarchy of terms.

EVOLUTION OF THE SOURCING FUNCTION

Historically sourcing, or purchasing, was regarded primarily as a clerical activity. This involved managing the buying transactions and filling out required forms. However, during the mid-1900s, particularly during World War II, the ability to acquire raw materials when needed became critical. Scarcity of many materials resulted in price increases, and finding affordable sources of supply became a managerial challenge. As a result, sourcing slowly moved from being a mere buying function to one responsible for cultivating suppliers and ensuring a large and continuous supply base.

The importance of sourcing has continued as companies now compete globally for sources of supply. In the late 1900s, supply chain competition became the norm and companies found that they were increasingly dependent on the performance of their suppliers. Further, technological developments in the early part of the 21st century created high expectations for supply chain integration, lower transaction costs, and faster response times. The Internet and B2B e-commerce changed the way sourcing of goods was conducted. As a result, the role of the sourcing function within the organization had became elevated, moving to the highest ranks of the organization, such as vice president of purchasing and vice president of supply. This evolution of the sourcing function is shown in Figure 6.3.

COMMERCIAL VERSUS CONSUMER SOURCING

Most people assume that they understand and have an expertise in sourcing as they are familiar with personal buying. However, commercial sourcing is very different from personal buying, or consumer buying. One difference relates to the number of buyers versus suppliers. In consumer buying there are many suppliers of common items and the buyers are typically final consumers of the items they purchase. Also, each individual buyer comprises a relatively small portion of the supplier's total business and has little ability to negotiate purchase price. Just consider the number of shoppers at Home Depot purchasing everything from light bulbs to refrigerators. Compare these transactions to those that take place between Home Depot and, say, the light bulb manufacturers.

FIGURE 6.3 The evolution of the sourcing function.

In commercial buying the volumes purchased are on a much larger scale and organizations typically have very specialized purchasing needs. Unlike in personal buying where there tend to be many choices of suppliers, in commercial buying the number of potential suppliers may be limited. Given the large volumes that are typically purchased, buyers in commercial sourcing spend large sums of money and suppliers may have a large stake in the individual customer. The stakes are high, sums of money very large, and often there is an imbalance in power based on the size of the buyer versus supplier. As a result companies may go to great lengths to secure the buying contracts. For example, many retail suppliers compete for a contract with a retailer such as Wal-Mart or Target where they can get a wide reach to the market.

The primary function of commercial buying is acquiring the right materials and services, and making sure they are available to all parts of the organization in the right quantities, at the right price, at the right time. Remember that there are many different items that are sourced that fulfill the needs of all parts of the organization, everything from materials directly used in manufacturing, to support services and office supplies. Sourcing must also make sure that it follows all legal and ethical procedures, and abides by environmental and security regulations. As a result commercial buying is much more complex than that of personal buying.

IMPACT ON THE ORGANIZATION AND THE SUPPLY CHAIN

The sourcing function provides a number of critical roles for the organization and the supply chain. The first is operational impact. The operational performance of an organization and its supply chain is dependent upon an efficient and effective sourcing function. It is sourcing that ensures that the right materials are available throughout the organization and supply chain, in the right quantities and at the right places exactly when needed. Sourcing must also do this while striking an optimal balance between having enough inventory and not too much. Shortages of materials can stop an organization from functioning. Too much inventory, on the other hand, can mean tied up capital and financial losses. Finding the right balance is an enormous task.

Sourcing also has a critical financial impact on the organization. Companies spend large sums of money on sourcing goods from their suppliers, and the savings that can result from proper management of this function can have a huge impact on the organization. Consider that in most manufacturing organizations the sourcing function represents the largest single category of spend for the company, ranging from 50% to 90% of revenue. In fact, almost 80% of the cost of an automobile is purchased cost, where the manufacturing facility merely assembles purchased items. The large financial impact of sourcing is precisely the reason this function has been elevated to such a prominent role in the organization.

Sourcing also has a significant strategic impact on the organization. Recall from Chapter 2 that all organizational decisions need to support the business strategy of the organization. This means that sourcing must find suppliers that support the company's competitive priorities. For example, companies that compete on cost will have different criteria for supplier selection than those competing on quality or other dimensions. Poor supplier quality may result in higher levels of scrap or returned items that slow down manufacturing. On the other hand, poor supplier management may result in paying significantly more for supplies than competitors. It is up to the sourcing function to ensure that the source of supply supports the strategic direction of the organization.

Another impact on the organization is risk mitigation, by minimizing risks of supply disruptions and erosion of image that can result from improper sourcing selection. Consider that sourcing is not a one-time event but occurs on a continual basis. As such, it is important to ensure a continuous source of supply rather than taking risks that may cause supply disruptions. This means evaluating suppliers not only on a one-time purchase basis, but as a longer-term source of supply. Also, sourcing must ensure that suppliers meet a range of performance standards, including legal and ethical. Sourcing from unethical suppliers, regardless of how low the cost, will erode a company's image.

Sourcing also has an information impact on the organization. Sourcing is continually gathering information on availability of suppliers and goods, prices, as well as new products and technology. It brings new knowledge to the organization and its supply chain. This helps companies in many ways, from having clear product cost expectations to understanding available technologies that can be used in product design.

SUPPLY CHAIN LEADER'S BOX—THE EXPANSIVE ROLE OF SUPPLIERS

Philips Lighting

Light-emitting diodes (LEDs), the silicon chips that burn brightly but consume far less energy than regular bulbs, are in their infancy as an industry. However, Philips Lighting is already positioning itself to be an industry leader even when LED components become a commodity. Philips wants to control the entire supply chain and has spent $5 billion on acquisitions to ensure controls of every link in the LED chain. They not only want to manufacture the chips, fixtures, and digital controls, but want to be able to combine all that into sophisticated systems for such customers as city governments and large corporations. They want to be a one-stop supplier for their customers.

In the past, Philips Lighting simply made light bulbs and fixtures without much consideration to the needs of individual customers. Now Philips is working with their customers from the start and bringing in outside partners to help design specialized products for them. They are linking distributors, architects, contractors and even banks to finance new lighting buyers.

One project is JW Marriott's 34-story hotel in Indianapolis. Working with local designers, Philips has custom-designed LEDs that fit into the ceiling, engineered the power system and light controls, calculated the energy savings, and offered financing advice. They have provided a one-stop service for Marriott and are doing so for other customers. Philips demonstrates the expansive role of suppliers.

Adapted from: “A Brighter Idea From Philips.” Business Week, November 30, 2009: 65.

THE SOURCING FUNCTION

THE SOURCING PROCESS

The sourcing function is responsible for every aspect of acquiring goods and services, ranging from identifying potential suppliers to negotiating and awarding contracts, and ensuring contract standards are met. The purchasing process begins when a purchase need within the organization is identified and clearly specified. The job of the sourcing function is to select appropriate suppliers, negotiate contracts, and manage the process of acquisition. Sourcing must first decide if the need can be met with existing suppliers or whether new suppliers must be identified. Sourcing typically maintains an acceptable list of suppliers for ongoing purchases, but also evaluates suppliers for new needs that occur on an ongoing basis.

Supplier selection is an important part of the sourcing function and involves identifying potential suppliers and soliciting business from them either in the form of a request for quotation (RFQ), a request for proposal (RFP), or a request or invitation for bid (RFB).

It is important for the sourcing function to be in charge of the supplier base and that supplier management and selection is directed through the sourcing function. “Maverick buying,” a practice where internal users attempt to buy directly from suppliers and bypass the sourcing function, often occurs in companies. It is acceptable for such practices to occur occasionally, such as a restaurant employee running out to buy bread or an office worker buying paper. However, this should not be done on a routine basis as it bypasses sourcing and erodes all the benefits sourcing brings to the organization, such as economies of scale when dealing with a large supply base.

The sourcing function must act as the primary contact with suppliers, but other functions should also be able to interact with suppliers as needed. Involving members from multiple functions improves the communication process with suppliers, especially when identifying needs and evaluating supplier capabilities. This may involve the function of engineering, to assess tolerance specification requirements for purchased items, operations in deciding which sourcing choice is better given the current production process, or even marketing to decide if product changes influenced by sourcing selection will impact sales. Companies often have sourcing teams and must consider inputs from all other organizational functions.

Sourcing personnel are responsible for understanding a range of material requirements and whether they can meet organizational needs. For example, it is the responsibility of sourcing to review material specifications and question whether a supplier's lower-cost material can meet the performance standards that may have been set by operations or engineering. Sourcing also needs to be able to review a number of different requisitions and identify whether different users require the same material, allowing it to combine purchase requirements and lower costs.

COST VERSUS PRICE

Sourcing managers are responsible for buying goods and services and determining fair price. For that reason they must understand the relationship between cost and price, remembering that cost and price are not the same. They must also understand what constitutes fair price under a range of circumstances.

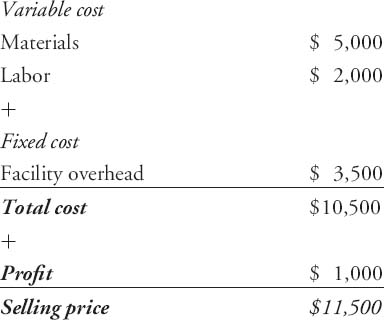

Cost is the sum of all costs incurred to produce the product. The total cost of producing a product, or service, is the sum of its fixed and variable costs. Recall from Chapter 5 that fixed costs are those the company incurs regardless of how much it produces, such as overhead, taxes, and insurance. For example, a company must pay for overhead and real estate taxes regardless of whether it produces 1 unit or 1,000 units. Variable costs, on the other hand, are costs that vary directly with the amount of units that are produced. They include items such as direct materials and direct labor. Together, fixed and variable costs add up to total cost:

![]()

- F = fixed cost

- VC = variable cost per unit

- Q = number of units sold

The price of an item is the amount at which it is being sold in the marketplace. Buyers understand that a supplier must cover total cost, including overhead, and make a profit in order to stay in business. The profit also needs to reflect the risks the supplier is taking. The goal in developing purchasing contracts and negotiation is to find a fair price, which is the lowest price that can be paid while ensuring a continuous supply of quality goods. This is illustrated in the following example:

A better way to evaluate price in purchasing is to estimate the total cost of ownership (TCO) before selecting a supplier. The reason is that there may be additional costs that are incurred when acquiring the item in addition to the selling price. Total cost of ownership is the purchase price plus all other costs associated with acquiring the item. This includes transportation, administrative costs, follow-up, expediting, storage, inspection and testing, warranty, customer service, and handling returns. In the above example these additional costs need to be added to the selling price to get a more accurate assessment.

BIDDING OR NEGOTIATION?

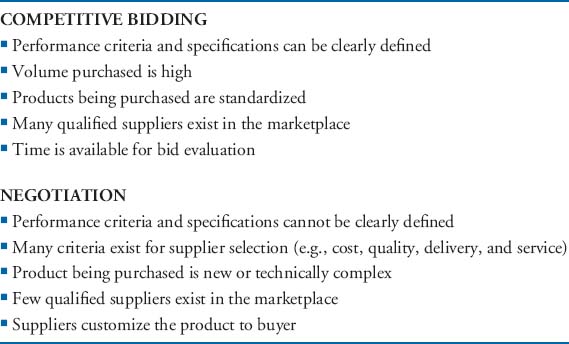

Another important role of the sourcing function is determining how to award buying contracts. Once suppliers have been identified, competitive bidding and negotiation are two different methods used to reach agreement and develop contracts with potential suppliers. Competitive bidding has the objective of awarding the business to the most qualified bidder, once specific criteria have been identified, and can pit suppliers against one another. Negotiation, on the other hand, is a communication process between two parties that attempts to reach a mutual agreement.

FIGURE 6.4 Criteria for using competitive bidding versus negotiation.

Both bidding and negotiation achieve the goal of reaching agreement and awarding a contract to a supplier, however, do so under different circumstances. A significant factor to consider is the type of relationship needed between buyers and suppliers. For purchasing standard items that are a commodity and that have standard specifications, such as stationary or cement, competitive bidding is the most efficient and effective method. However, when there are many factors to consider in awarding a contract, and when it is important to work with suppliers in product development, it is best to rely on cooperative negotiation. Consider Figure 6.4.

SOURCING AND SCM

FUNCTIONAL VERSUS INNOVATIVE PRODUCTS

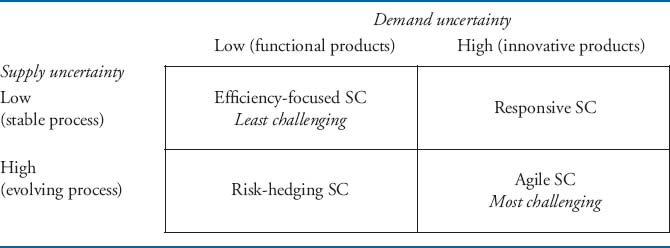

Supply chains have uncertainty on both the demand and supply side. Demand uncertainty occurs when product demand is unstable and difficult to predict. Supply uncertainty occurs when there is uncertainty regarding sources of supply and their capabilities. Demand and supply uncertainties are related to the type of product and their supply chains. Understanding these uncertainties makes it easier to manage the supply chain.

GLOBAL INSIGHTS BOX—FUNCTIONAL PRODUCTS CHALLENGE

Global Fast Food Markets

Even functional products can experience uncertainty in demand in certain markets. Consider the case of the fast food market in China. Yum! Brands, which includes KFC and Pizza Hut chains, has done extremely well in the Chinese fast food market. However, sales have been dropping at Chinese outlets in the recent past, and there are fears that Chinese tastes may be shifting away from Western cuisine. Some analysts think that China may be saturated with Western brands, especially in the big cities. The novelty may have worn off and preferences may be shifting back to local tastes.

Even typically stable products experience demand shifts due to a variety of factors. Yum's Brand is now experiencing competition it did not have before from local rivals. A few years ago having air conditioning and clean restrooms in China was an order winner and brought in customers. Today, Chinese chains are expanding and offering these same amenities, often with help from global investors. Also, McDonald's is refocusing in China and planning to open as many as 175 new mainland restaurants and offering free Wi-Fi. What was a predictable product market just a few years ago is changing and requiring Yum to think about repositioning its product offering.

Adapted from: “Is China Fed Up With The Colonel's Chicken?” Business Week February 22, 2010: 30.

Two broad categories of products result in very different supply chains and have differing levels of demand uncertainty. Products can be classified as either primarily functional or primarily innovative.1 Depending on their classification, they will be sourced differently and will require different types of supply chains. Functional products are those that satisfy basic functions or needs. They include items such as food purchased in grocery stores, gas and oil for transportation and heating, and household items from batteries to light bulbs. In contrast, innovative products are purchased for other reasons, such as innovation or status, and include high fashion items or technology products, such as those seen in the computer industry.

Functional products typically have stable and predictable demand and long life cycles. It is easier to source for functional products due to this stability. Their supply chains are easier to manage; however, they typically have low profit margins. Innovative products, on the other hand, have highly unpredictable demand and short life cycles. New and innovative products are introduced quickly and their demand is difficult to forecast. Although they have higher profit margins their supply chains are much more difficult to manage.

FIGURE 6.5 Demand versus supply uncertainty.

Just as there are uncertainties on the demand side, there are also uncertainties on the sourcing side. The supply side of the supply chain can be classified as a stable or an evolving supply process. A stable supply process is where sources of supply are well established, manufacturing processes used are mature, and the underlying technology is stable. Consider sourcing apples, lumber, or undershirts. In contrast, an evolving supply process is where sources of supply are rapidly changing, the manufacturing process is in an early stage, and the underlying technology is quickly evolving. Examples would include alternative energy sources, certain organic food items, or high-end computer technology. It is challenging to manage supply chains with either demand or supply uncertainty. It is especially challenging to manage supply chains with both uncertainties as shown in Figure 6.5.

Efficiency-focused supply chains have both low demand and supply uncertainty and are easiest to manage. These supply chains typically don't have high profit margins. However, their operations are highly predictable and the gains in these supply chains come from efficiency and elimination of waste.

Responsive supply chains are used for innovative products that have a stable supply base. The primary challenge here is to ensuring being able to quickly respond to customer demands. Mass-customization strategies such as postponement, where the supply chain is designed to delay product differentiation as late in the supply chain as possible, are effective here. A good example is the case of HP printers that are kept in generic form as long as possible. They are differentiated with country and language specific labels that are added at the last point in the system.

Risk-hedging supply chains are those with high uncertainty on the supply side. These supply chains must do everything possible to minimize risks of supply disruptions and inventory shortages. These supply chains typically rely on higher inventory safety stocks and engage in a practice where resources are pooled and shared between different companies.

SUPPLY CHAIN LEADER'S BOX—INNOVATIVE PRODUCT CHALLENGE

Apple Computer Corp

Apple Computer Corporation is known for its innovative products and an agile supply chain. Its iPad is a classic example of a high technology innovative product with an uncertain market. Following its launch numerous analysts made estimates of product demand, with an average estimate ranging between three to four million iPads sold in its first year. Estimates were also being made on how Apple would price the iPad, understanding the challenges of estimating the price for such a product.

The research firm iSuppli estimated that the gross margins for the product would likely start at 54% and it would be the envy of the computer business world, allowing room for the product to get cheaper as imitators came along. iSuppli gave the following price breakdown of some of iPad's parts, giving an idea of what the cost to produce might be. The breakdown is as follows:

| – $35.30 | |

| – $29.50 (for 16GB model) to $118 (for 64 GB) | |

| – $80 (9.9-inch color touch screen) | |

| – $17.50 | |

| – $35.15 | |

| – $17 | |

| – unknown (proprietary) |

Although the gross margin might seem high, given the average selling price being in the range of $600, one has to consider the risks that the company takes with these innovative products. One strategy that Apple uses to help mitigate these risks is to use versions of the same operating system for its products—including the Macs, iPhones, iPods, and now the iPad—a system it developed in 2000. It is an unusual strategy for a hardware company to also create its own operating system to run devices. The fact that Apple has such a durable platform that can be used across many products enables it to reduce risks on the supply side and gives it a huge advantage over its competitors.

Adapted from: “The iPad: More Than the Sum of its Parts. $270 More, Actually.” Business Week, February 22, 2010: 24.

Agile supply chains are used in cases of both high demand and supply uncertainty. They are the most difficult to manage as they simultaneously must be responsive to an uncertain demand while using strategies to hedge risks to ensure there are no supply disruptions. These supply chains use mass customization strategies on the demand side, while carrying higher safety stock and engaging in resource pooling on the supply side.

SINGLE VERSUS MULTIPLE SOURCING

Traditionally companies held the view that multiple sources of supply were best in order to increase cost competition and ensure supply security. This view has been challenged for quite some time and the notion of single sourcing is becoming the acceptable norm. Single sourcing focuses on building closer supplier relationships and cooperation between buyers and suppliers, and moves away from arms-length relationships. It focuses on moving away from competitive bidding, using cooperative negotiation, and building long-term relationships.

Single sourcing has a number of benefits. Splitting the order among multiple suppliers can be costly as it doesn't permit consolidating purchase power. Splitting the order also has an impact on quality as there will be natural variations between different sources, even if minimal. Single sourcing also lowers freight costs, enables easier scheduling of deliveries, and the supplier may be more cooperative in addressing special needs knowing they are the only source.

In some cases there may not be a choice but to go with a single source. This may occur, for example, when a supplier is the only source of a particular material. They may be the only one that has the needed process or they are the sole owner of the patent for the product. Having a single source of supply, however, is risky in practice. When a supplier is small the buyer's business may utilize most of the supplier's capacity. This makes the supplier highly vulnerable if there is a discontinuity of purchase from the buyer. At the same time the buyer may not wish to be tied to a source that is so highly dependent upon them. Similarly, by relying on one supplier the buyer is vulnerable if there is a disruption in the supplier's production process, such as a fire at a plant, a labor strike, or a work stoppage as the supplier's supplier has a problem.

One strategy companies should consider is to use a “portfolio” of a small number of multiple suppliers. Similar to a financial portfolio, these suppliers can be selected to create a balance of requirements. Some can be local for rapid deliveries; others may be global but less expensive. This strategy can help balance the risks of relying on a single supplier in case of supply chain disruptions. Another rule to consider is that one buyer should not make up more than 20% or 30% of the total supplier's business, otherwise making the supplier highly vulnerable.

DOMESTIC VERSUS GLOBAL SOURCING

Another challenge to consider is whether to use domestic or global sourcing, also called “off-shoring.” Global sourcing has been on the rise as companies have been attracted to cheaper labor costs in other parts of the world. It has been most prominent for sourcing products with easily defined standards, such as in the retail industry. It is also used heavily in the service industry, such as running call centers, processing claim forms, or in software development. Even in medicine reading of diagnostic tests, such as x-rays, is often off-shored. However, with a rise in fuel prices the labor savings are often negated, or even outweighed, by high transportation costs. Therefore, a number of companies are turning toward domestic sources to reduce transportation costs, monitor quality more closely, and have closer buyer-supplier relationships. Also, with an emphasis on sustainability and “green” there has been a push toward sourcing local versus global goods.

Companies that engage in global sourcing need to possess a certain amount of multinational experience. This can be especially problematic for small- to medium-sized firms that are more likely to lack this expertise. Global sourcing, by definition, requires workgroups of individuals from different companies, different cultures and languages, to work together effectively. This concept, known as virtual teaming, poses special challenges due to the significant potential for culture clashes and misunderstandings. These differences in culture and business practice can put offshore source initiatives at risk, particularly for enterprises with limited international experience.

OUTSOURCING

An important sourcing decision is whether to “outsource” certain aspects of the sourcing function. Recall that outsourcing involves choosing a third party, such as an outside supplier or vendor, to perform a task, function, or process, in order to incur business benefits. Companies may choose to outsource activities or tasks for many reasons, rather than performing them internally. These include lower costs, access to technical skills, and the ability to free themselves of doing noncore activities.

Outsourcing has become a mega trend in many industries and is continuing to grow, as companies focus on their core competencies and shed tasks perceived as non-core. A good example has been the growth in outsourcing of transportation of goods to third-party logistics (3PL) providers, such as UPS and FedEx. Transportation and movement of goods requires investment of specialized resources, such as fleets of trucks, aircraft, and state-of-the-art information system for product tracking. Outsourcing this activity to specialty companies is a much more cost-effective decision for most firms. Good outsourcing decisions can result in lowered costs and a competitive advantage, whereas poorly made decisions can increase costs, disrupt service, and even lead to business failure. Although financial aspects of outsourcing are important, outsourcing has increasingly taken on a broader strategic organizational focus.

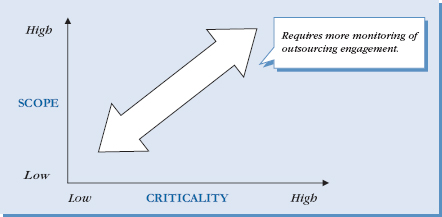

Two key dimensions that help define outsourcing are the scope and criticality of the outsourced task. Scope is the degree of responsibility assigned to the supplier. Criticality, on the hand, is the importance of the outsourced activities or tasks to the organization. The greater the scope of the outsourced task the larger the relinquishing of control by the buyer. Similarly, the greater the criticality of the outsourced task the greater the consequences of poor performance to the buying firm and greater the requirement for supplier management. It is important to understand these dimensions when considering outsourcing. Companies should be especially careful when outsourcing activities with large scope and criticality, and should especially monitor such outsourcing engagement to ensure a successful outcome, as illustrated in Figure 6.6. We discuss the importance of scope and criticality in more detail in Chapter 13.

FIGURE 6.6 Dimensions of outsourcing.

ELECTRONIC AUCTIONS (E-AUCTIONS)

E-auctions are the use of Internet technology to conduct auctions as a means of selecting suppliers and determining aspects of the purchase contract. This includes determination of price, product quality, volume allocation to different suppliers, as well as supplier delivery schedules. Auctions have been used throughout history as a means of providing competition between suppliers. It is Internet technology, however, that has given sourcing managers an important tool for supplier selection to conduct this process online in an efficient and effective manner. E-auctions have enabled increasing the pool of potential suppliers for any one item and to more efficiently and accurately compare sources of supply.

There are many benefits to using e-auctions. They include market transparency, decreased error rate, and simplified comparison of sources of supply. They also include increased buying reach as companies can tap into a much broader source of supply through the use of the Internet. There is also a reduction in ordering cycle time as the process is automated and more efficient than the traditional method of sourcing, such as issuing an RFP or RFQ.

There are, however, potential problems with e-auctions that must be considered. One problem is that suppliers can bid unrealistically low prices during the e-auction process, with the idea of renegotiating after the contract has been awarded. As a result potentially better and more realistic sources of supply may be eliminated. Another problem is the inclusion of suppliers in the e-auction who do not actually plan on participating, but merely want to gather market intelligence. There are also risks to interrupting a good supplier relationship. Putting products on an e-auction sends a signal to current suppliers that the company is considering switching to a new source of supply and that price may be the determining factor in source selection. This may potentially damage good supplier relationships and may not be the best strategy when building long-term relationships.

MANAGERIAL INSIGHTS BOX—OUTSOURCING ALLIANCES

Roots

The Canadian apparel manufacturer and retailer, Roots, is an example of a company that succeeded as a result of shifting its sourcing strategy to involve collaboration with its supplier, and demonstrates the benefits that can be attained from supplier collaboration. Roots, a company with a stellar reputation, was given the task of handling licensed USA logo Olympic wear during the 2002 Winter Games in Salt Lake City. The forecast called for 100 calls per day into the Roots customer service center, which was well below the actual 1,500 per day peak. However, the 2002 Winter Games experienced a surge of patriotism, following the September 11 attacks. The result was an unexpected flood of demand that Roots was initially unable to meet. Roots found itself unable to handle the 50,000 orders per month for USA Olympic gear from its Canadian operation. At the last minute, the company was forced to revamp its entire distribution strategy, opening a separate web-based ordering channel. With the help of a third-party call center and fulfillment provider, it added two U.S.-based call centers, moved distribution to Memphis, and changed delivery carriers. The company did this almost overnight while orders were still flooding in.

The company's forecast of expected demand was based on two of the prior Olympic events. Based on this forecast of demand raw materials were ordered, production was scheduled, and a third-party relationship for a call center and fulfillment operation was set up. However, the surge in demand in the post 9-11 climate was not anticipated. Further, Roots manufactures locally in Canada, so it has a short supply chain for finished products resulting in lower inventory levels. Roots quickly realized that it could not succeed alone and needed a partner. Roots turned to its 3PL provider. Together they quickly set up a system that involved reporting, check points, and audits throughout the fulfillment chain. The systems were scalable and well planned, rules and procedures were in place, and it was clear who had what authority regarding issues such as customer service, manufacturing, or distribution. The system turned out to be a success allowing Roots to meet its orders. Building a close relationship with its 3PL has helped Roots showcase its brand and serve the market as a first class retailer.

Adapted from: “Roots Chooses PFSweb for Olympic Fulfillment Support: Outsourcing Partner Ramps Operations to Meet Business Wire, February 26, 2002.

There are many types of e-auctions that are classified based on the way competition between sellers or buyers is conducted. For example, in an open auction, suppliers can select the items they want to place offers on, see the most competitive offers from other suppliers, and enter as many offers as they want until a specified closing time. In a sealed bid auction, sellers have a certain amount of time to submit one best and final bid, with bidders never having knowledge of what the other sellers are bidding. With forward auctions, bids increase in value, whereas in reverse auctions they decrease in value.

The most common type of e-auction is the reverse auction, which involves one buyer with many sellers. Sellers place decreasing bids on a set of goods or services and follow a specified set of rules that governs the auction. A reverse auction is an online, real-time declining price auction involving one buyer and a number of prequalified suppliers. The bidding process is dynamic. Suppliers compete for the business by bidding against each other online using specialized software. Suppliers are given information concerning the status of their bids in real time and the supplier with the lowest bid is usually awarded the business.

E-auctions are one of many methods for sourcing goods and services. To use eauctions for sourcing there are a few criteria that need to be in place. First, the specification for goods or services needs to be well defined. Buyer expectations must be clear, including product characteristics, quality standards, technological requirements, as well as delivery expectations. Second, there must be a competitive market in place and a sufficient number of qualified suppliers. Too few suppliers may not provide enough competition, whereas too many may create confusion. A rule of thumb suggests that the number of suppliers participating in an e-auction should be between three and six. Third, there must be a clear understanding of market standards in order to set appropriate expectations. Fourth, the buyer believes the cost of the e-auction is justified by the savings in price. This item is often overlooked as running an e-auction, including software and training, can prove to be more expensive than most companies anticipate. Fifth, clear rules for running the e-auction are specified, such as extending the auction and selection criteria.

The e-auction process involves three stages: preparation, the auction event, and follow-up. In fact, preparation is often the determining factor of an e-auction's success or failure. In the preparation stage, the buyer must identify and prequalify suppliers who will participate. The buyer must also set the product requirements—such as quality, quantity, delivery, service, and the length of contract. In addition, they must train everyone involved in the technology that will be used to run the auction and pretest the auction technology to ensure functionality. They must also specify how the auction will be conducted. For example, suppliers must understand how long the auction will run and the rules if the targeted closing time will be extended. Some e-auctions have a “hard” closing time, which permits no extension of time, whereas other auctions permit time extension. Typically an e-auction will experience a surge of activity in the last few minutes of the auction and it is important for suppliers to understand these types of rules governing the auction to adjust their behavior accordingly.

Today's technology allows the buyer a variety of alternative approaches in terms of conducting auctions. For example, price visibility can be viewed in many ways, such as a rank order, by percentages, or by proportional differences. The technology also allows the ranks to be adjusted for non-price factors, such as differences in transportation costs, quality, or delivery time. Most auction software allows suppliers and the buyer to communicate with each other during the auction, and the software options can specify whether messages may be visible to other suppliers participating in the auction. In addition, technical assistance must be made available during the auction in case problems arise.

Conducting e-auctions is much more complicated, and often more expensive, than companies realize. It also automates the buyer-supplier relationship, diminishing the potential of building a long-term relationship. Although e-auctions can provide large benefits in sourcing, companies should be selective when using this sourcing approach.

MEASURING SOURCING PERFORMANCE

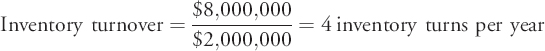

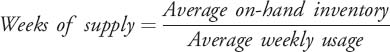

As we can see, the sourcing function has a large responsibility over supply chain inventory. Sourcing must ensure that there are enough inventory items needed at the right locations, but not too much inventory given large inventory costs. There are two common performance measures that can be used to measure the performance of the sourcing function relative to its utilization of inventory. These are inventory turnover and weeks-of-supply.

Inventory turnover measures how quickly inventory moves. It is computed as:

![]()

Examle 6.1 Jenco Incorporated is a producer of children's dolls for the toy industry. It has high inventory costs and is concerned that its inventory is selling at an appropriate rate. It has an annual cost of goods sold of $8,000,000 and an average inventory in dollars is $2,000,000, what is the annual inventory turnover?

solution:

In general, the higher the inventory turnover rate the better the company utilizes its inventory. However, there is no one number that is considered correct. Some companies need to turn their inventories over faster than others. For example, perishable items such as food or medicine need to turn over faster than machinery or commodity items. Also, certain industries have much higher inventory turns than others. For example, innovative products with short life cycles need to turn over very quickly or they may become obsolete. To get good guidelines on acceptable inventory turns it is important for companies to consider their industry standards as a benchmark of performance.

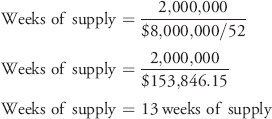

The second performance measure, weeks of supply, provides the length of time demand can be met with on-hand inventory. It is computed as follows:

Example 6.2 Jenco Inc. is concerned about having enough inventory in stock and wants to compute its weeks of supply. Recall that we already know that Jenco has an $8,000,000 annual cost of goods sold.

Solution: Weekly cost of goods sold can be computed by dividing the annual cost of goods sold by 52 weeks per year. Weeks of supply can then be computed as follows:

Weeks of a supply tells the manager how long the current on hand inventory will last based on current demand. A large “weeks of supply” value means too much inventory is being held, whereas a value that is too low increases the chances of a stock-out or lost sales. Notice that the value of this metric depends on demand. Given that product demand often changes due to factors such as seasonality, managers need to consider that the best value of this metric will likely change throughout the year. As with inventory turnover, companies should benchmark this metric against industry best practices.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Sourcing is the business function responsible for all activities and processes required to purchase goods and services from suppliers.

- Terms such as “purchasing,” “procurement,” “sourcing,” “strategic sourcing,” and “supply management” are used interchangeably but are not the same. Purchasing defines the process of buying goods and services, whereas strategic sourcing, or supply management, involve looking at sourcing from a strategic and future oriented perspective.

- The sourcing function provides a number of critical roles for the organization. These are operational impact, financial impact, strategic impact, risk mitigation impact, and information impact.

- The sourcing process involves every aspect of acquiring goods and services, ranging from identifying potential suppliers to negotiating and awarding contracts, and ensuring contract standards are met.

- Competitive bidding and negotiation are two different methods used to reach agreement and develop contracts with potential suppliers.

- Products can be classified as either primarily functional or primarily innovative. Depending on their classification, they will be sourced differently and will require different types of supply chains.

- Outsourcing engagements can be classified based on scope and criticality of outsourced tasks.

- E-auctions are the use of Internet technology to conduct auctions as a means of selecting suppliers and determining aspects of the purchase contract.

- Inventory turnover and weeks of supply are two metrics that can be used to measure performance of the sourcing function.

KEY TERMS

- Sourcing

- Purchasing

- Strategic sourcing

- Operational impact

- Financial impact

- Risk mitigation

- Information impact

- Fair price

- Total cost of ownership (TCO)

- Functional

- Innovative

- Stable

- Evolving supply process

- Postponement

- Inventory turnover

- Weeks-of-supply

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Identify the primary ways in which the sourcing function impacts supply chain management (SCM). Find an industry example where sourcing has significantly benefited the firm and where it has significantly hurt the firm.

- Think of a recent purchase you made in your everyday life. Explain how this purchasing process would be different if you were buying the same product for a firm on a regular basis versus purchasing it for yourself.

- Find at least one business example of outsourcing. Explain the risks and benefits.

- There has been in a push in many communities to source locally. Identify the risks and benefits of sourcing globally versus locally.

- Explain the differences between sourcing manufactured products versus services. Identify some key challenges that would occur in defining service specifications versus manufacturing specifications. Provide an example of each.

PROBLEMS

- Jerry's Auto Repair is concerned about the effective use of parts inventory. His average inventory in dollars is $300,000 and cost of goods sold is $1,500,000.

- What is the inventory turnover for Jerry's Auto Repair?

- Assuming 52 weeks per year, what is the weeks of supply?

- What do these numbers tell you about Jerry's inventory utilization?

- Urbanite Hip is a clothing store catering to college students and young professionals. It carries fashion merchandise and wants to ensure that it is using inventory effectively. Cost of goods sold is $5,000,000 and average inventory in dollars is $250,000.

- What is their inventory turnover?

- What is the weeks of supply, assuming 52 weeks per year?

- Urbanite Hip is expecting to increase sales by 10% next year while maintaining the same level of average inventory. How will their inventory turnover and weeks of supply change?

- Phoenix & Chow is a family-owned restaurant with an annual cost of goods sold of $520,000 and an average inventory of $50,000. What is the value of weeks of supply assuming 52 weeks per year?

- H & H store is a retailer of stationary and paper products. It has an annual cost of goods sold of $100,000 and an average inventory of $50,000. What is the annual inventory turnover? If the industry average is 3 turns per year, how does H & H compare?

- Climb and Fly Sports has annual cost of goods sold of $1 million. What is the average inventory assuming 52 weeks per year and weeks of supply equal to 5?

CLASS EXERCISE: TOYOTA

You are Manager of Strategic Sourcing at Toyota Motor Corporation and have just been called in by the VP of Global Sourcing, to whom you report. There has been a problem with at least eight vehicles exhibiting sticking accelerator pedals and your boss is very upset. Strong evidence points to a problem with CTS, an electronics supplier, which has been recognized for high-quality standards by Toyota. You have been asked to provide your boss with the following:

- Identify the exact sequence of steps—a “project plan”—on how to handle this problem, from dealing with customers to identifying causes. Explain what should be done and why.

- What should be said to your customers? How should you explain the problem?

- What information do you want to collect and from who to identify causes?

- What should you say to your supplier? How should you say it (e.g., in public or private; in a meeting or in writing)? What action do you expect them to take?

- Do you continue long term contracting with this supplier? Do you penalize this supplier?

- What are the risk trade-offs in your decision (e.g., placing blame versus accumulating evidence; dropping a supplier versus standing by a supplier)?

CASE STUDY: SNEDEKER GLOBAL CRUISES

It was August 7th and Brandt Womack had just been given his first assignment by his purchasing manager at Miami based Snedeker Global Cruises Inc. It was the “E-Auction Development Program” (EDP). The purpose of EDP was to identify potential products that could be purchased through e-auctions, to determine the necessary steps to conduct a successful e-auction, and assess the impact of e-auctions on supplier relationships. As a newly hired supply chain manager Brandt wondered how to proceed.

Snedeker Global Cruises incorporated in 1986 and is a cruise company with 35 cruise ships and over 70,000 berths. Snedeker Global serves the contemporary and premium segments of the cruise vacation industry and offers a variety of itineraries to destinations worldwide, including Alaska, Asia, Australia, the Caribbean, Europe, Hawaii, Latin America, and New Zealand.

In 2005, Snedeker incurred its highest-ever procurement costs in sourcing the products and services needed for cruise ship operations and wanted to combat this trend. To that end Snedeker had been working on changing its buying practices. In the past, each individual cruise ship made all of its own purchases for the upcoming season. Purchasing was decentralized, with each ship making purchasing decisions based on its needs alone. The company began moving away from this practice and put into place a centralized purchasing department in charge of making purchases for the entire cruise line. The centralized purchasing strategy provided many cost-saving opportunities for the company and greatly reduced the overall order costs of the company. The company wanted to continue to pursue ways in which the centralized purchasing practice could reduce costs and e-auctions became a viable option. However, senior management at Snedeker was concerned about the impact on quality and the effect e-auctions might have on suppliers.

At Snedeker, the purchasing cycle began with a master forecast for the upcoming year with orders being placed eight to 10 months prior to need. This master forecast included everything from replacement engine parts to chocolate mints placed on pillows in cabins. When the forecast was generated it was given to the Senior Purchasing

Manager, Kasey Davis. Kasey scheduled a meeting with Brandt to discuss the E-Auction Development Program giving Brandt the master list of all the products needing to be purchased for the next year. Kasey instructed Brandt to determine which products would be best to purchase through e-auctions and wanted to know how the e-auction process would work. In addition, Kasey wanted Brandt to determine the effect that e-auctions would have on relationships with current suppliers.

Brandt walked out of Kasey's office overwhelmed. It was his first assignment and he did not know where to begin the E-Auction Development Program (EDP).

CASE QUESTIONS

- Suggest steps Brandt should follow to begin the EDP process.

- Identify differences between traditional purchasing and use of e-auctions. How can Brandt use these differences to make his selection? What types of items would be best suited for purchase through e-auctions?

- Assume Brandt has identified products to purchase through e-auctions. What steps does he need to take to conduct a successful e-auction?

- What negative impact can e-auctions have on supplier relationships and how can Brandt ensure that they do not occur?

REFERENCES

Aftuah, A. “Redefining Firm Boundaries in the Face of the Internet: Are Firms Really Shrinking?” Academy of Management Review, 28(1), 2003: 34–53.

Amaral, J., C. A. Billington, and A. A. Tsay. “Outsourcing Production Without Losing Control.” Supply Chain Management Review, 8(8), 2003: 44–52.

Coase, R. H. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica, 4(1), 1937: 386–405.

Ellram, L. “Purchasing: The Cornerstone of the Total Cost of Ownership Concept.” Journal of Business Logistics, 14(1), 1993: 161–183.

Ellram, L. “A Taxonomy of Total Cost of Ownership Models.” Journal of Business Logistics, 15(1), 1994: 171–191.

Fisher, M. L. “What is the Right Supply Chain for Your Product?” Harvard Business Review, March–April 1997: 105–116.

Hamel, G., and C. K. Prahalad. “The Core Competence of the Corporation.” Harvard Business Review, 68(3), 1990: 243–244.

Hamel, G. and C. K. Prahalad. Competing for the Future. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1996.

Lambert, D. M., A.M. Knemeyer, and J. T. Gardner. “Supply Chain Partnerships: Model Validation and Implementation.” Journal of Business Logistics, 25(2), 2004: 21–42.

Lee, H. L. “Aligning Supply Chain Strategies with Product Uncertainties.” California Management Review, 44(3), Spring 2002: 105–119.

Trent, Robert J. Strategic Supply Management. Fort Lauderdale, Florida: J. Ross Publishing, 2007.