17.5. R&D PRODUCTIVITY

In this section, the emphasis is on R&D productivity at the national level. R&D productivity at the organizational level is discussed in the chapter, "Creating a Productive and Effective R&D Organization." R&D organization productivity is defined as an organization effectiveness vector that includes quantifiable and nonquantifiable organization outputs, and this vector reflects the quality and the relationship of outputs to organizational goals and objectives. Individual researcher productivity follows the general pattern of the organization effectiveness vector and is discussed in the chapter on performance appraisal.

Figures 17.3 through 17.6 provide information about the magnitude of selected countries R&D investments. In addition to the monetary investment, in the long run, the ability of a nation to conduct research in science and technology is constrained by the ability of the nation's education system to produce the necessary science- and engineering-trained manpower.

It is difficult to compare the training of engineers and scientists from different countries because the curricula vary and the quality of training and the degrees conferred convey different meanings. Consequently, the number of engineers and scientists that a country trains may not predict its strength in science and technology. Nevertheless, the number of scientists trained is an indication of disciplinary emphasis by the country, and, over time, this is bound to affect the ability of the country to conduct research in science and technology. Therefore, it is important to note that in 2006 several countries awarded higher percentages of their first university degrees to candidates in the natural sciences and engineering than the United States (32 percent—456,000 S&E graduates). These include China (56 percent—672,000), Japan (63 percent—349,000), the European Union (38 percent—617,000), the United Kingdom (38 percent—110,000), and Germany (62 percent—51,000). It's also important to note that at 32 percent the United States is below the world average of S&E graduates.

The figures for developing countries, where higher education is still a relatively elitist commodity, are somewhat misleading. China, for instance, has the lowest percentage of colleague cohorts obtaining a college degree (1.67 percent) compared with the United States, which has the highest percentage of population receiving tertiary education (39 percent) (Science and Engineering Indicators, 2006).

In addition to the number of engineers and scientists produced by a nation, R&D productivity is also a function of the quality of the training, effectiveness of R&D management, availability of modern research equipment, and computer technology. Some surrogates of R&D productivity could be the extent of the scientific literature, the number of patents, and the overall economic activity represented by the gross domestic product (GDP).

17.5.1. Scientific Literature

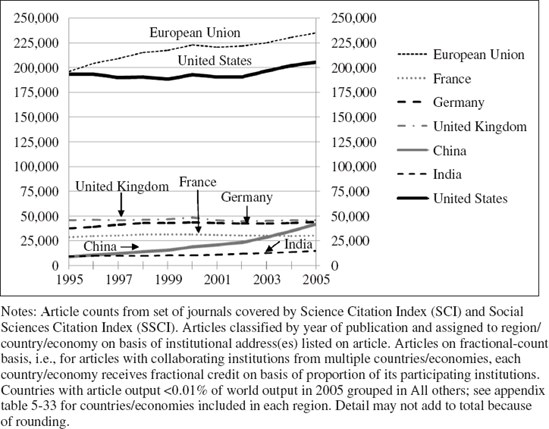

The relative strength of a country's R&D activities can be measured, to some degree, by its share of publications in the world's leading scientific journals. The United States share of world scientific and technical articles is shown in Figure Figure 17.10 and Table 17.5 (National Science Board, 2008, Appendix Table 5-34, p. A5-57). Relative ranking of countries' output of S&E selected fields is shown in Table 17.6. Table 17.6 demonstrates that the United States, as of 2005, is still ranked first in output in every category of technical article. Perhaps more significant than this is that the United States held 54 percent of the top 1 percent cited articles (National Science Board, 2008, Appendix Table 5-39, p. A5-74). This alignment of data would suggest that although the United States may be producing less information than the 27 countries of the European Union, the quality of the information produced is recognized as being one of the highest caliber. When looking at the rate of article growth, it becomes evident that this lead is not secure. With the Asia-10 countries increasing at a rate of 6.6 percent from 1995 to 2005 and the United States growing at a rate of only 0.6 percent per year in the same time frame, Asia may in time surpass the United States in article output.

17.5.2. Patents

Data on patent activity permit some overall comparisons of the output of inventors in different countries. Significant inventions are patented in the host country and in other countries as well. Thus, the number of U.S. patents granted to foreign inventors provides an indicator of the level of invention in those countries, while the proportion of foreign to U.S. inventors receiving U.S. patents provides a measure of the comparative inventiveness of foreign versus U.S. inventors. Figures 17.14a and 17.14b show number of triadic (three or more) families by nationality of inventor for selected countries and patents in force by country of origin, respectively. In 2005, applications from Japan and the United States counted for 28 percent and 21 percent, respectively of the patents in force worldwide. Also, in Figure 17.1 it can be seen that the United States continues to produce and sell more usable intellectual property than other countries. This denotes the existence of innovative culture of America. Similarly, data gathered between 2001 and 2003 shows that the United States owns 17.5 percent of foreign inventions (a 5.5 percent increase over data collected from 1991 to 1993). However, foreign ownership of U.S. inventions from 2001 to 2003 has risen 5.6 percent since 1991–1993, from 8 percent to 13.6 percent. In order for the trend demonstrated in Figure 17.1 to continue, the United States must continue to invest in basic research and applied research.

Figure 17.10. S&E Articles in Selected Fields, by Region/Country/Economy: 1995–2005: (Sources: Thomson Scientific, SCI and SSCI, http://scientific.thomson.com/products/categories/citation/;ipIQ, Inc.; and National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics, special tabulations.)

| Number of Articles | Percent of Total | Average Annual Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| World | 709,541 | 100% | 2.3 |

| United States | 205,320 | 29% | 0.6 |

| European Union | 234,868 | 33% | 1.8 |

| Asia-10 | 144,767 | 20% | 6.6 |

| Source: Science and Engineering Indicators, 2008, Appendix Table 5-34, p. A5-57. | |||

Another trend in patent activity that may indicate the condition of America's innovation is the number of foreign co-authors on American patents: this trend can be viewed either positively or negatively. It is a positive trend if it reflects a globalization effort on the part of US scientists to be actively engaged in the greater intellectual community beyond its domestic borders. This will allow technology transfer to occur and general scientific knowledge to increase in developing countries at a higher rate, further increasing their rate of economic development, which will in turn allow new markets to be formed in otherwise undeveloped regions of the world. The trend may be negative if it reflects foreign scientist's efforts to displace U.S. scientists in domestic research, further pushing the U.S. scientific community into the reputation of adopting and adapting to foreign inventiveness. Regardless of the interpretation, the data collected by the OECD Patent Database in 2007 shows that the number of foreign co-authors has nearly doubled, from 6.7 percent in the early nineties to 12.2 percent at the turn of the century (OECD, 2009).

17.5.3. Economic Activity

In a real sense, successful inventive and innovative activity over time should result in increases in an economy's ability to produce goods and services in a cost effective manner. Increased productivity and the resulting improvements in the standard of living for the nation's citizens are clearly the important benefits of an R&D activity. Consequently, one measure of the impact of science and technology on society is the value of the production accounted for by each employed person. Gross domestic product (GDP) measures the value added by industry and individuals in each country. In addition to the input provided by science and technology, GDP per employed person reflects factors such as availability of natural resources, expertise of the workforce, investment in industry, and many other social and economic factors. Among the many sources of productivity growth, science and technology have been identified as major causal factors. GDP, therefore, to a great extent represents the strengths of science and technology of a nation. Real GDP per employed person in selected countries is shown in Figure 17.12.