I think intellect is a good thing unless it paralyzes your ability to make decisions because you see too much complexity. Presidents need to have what I would call a synthesizing intelligence.

People have different requirements. We sometimes forget that; we simply presume there is "us." We do not even acknowledge the diversity of what people expect from an organization in the way we define the term organization itself. Most people define an organization as a group of people sharing the same objectives. Seldom is this the case. Employees are looking for career opportunities, a stable income, and a chance to develop their skills. Shareholders look for a financial return. Customers look for a good deal, while suppliers see your organization as a source of profit themselves. Not only do people have different requirements—often they are flat-out conflicting ones.

Organizational theorists will be quick to point out that having different requirements actually is the whole point of paying out a salary to employees, instead of seeing them as individual entrepreneurs. A salary can be defined as the compensation for giving up your time and personal objectives and contributing to the organization's objectives. However true this may have been in the industrial age, and for the larger part of the twentieth century, a salary is not what motivates employees today. Today's generation is motivated by meaning and purpose, and creating a healthy work/life balance,[143] a true you-and-me dilemma to start with.

You-and-me dilemmas can be found everywhere, in multiple shapes and forms. They can exist between stakeholders of the organization, such as shareholders having a different goal than the unions, or the regulators, or society at large. In fact, an organization is better defined as a unique collaboration of stakeholders that through the organization each reach goals and objectives that none of them could have reached by themselves. For that, they need to reconcile their differences.

You-and-me dilemmas can be found within organizations, where the back office and the front office have conflicting requirements. The back office may look for standard processes and smooth operations, while the front office is served better with all the flexibility to match customer demand exactly. And the two responsible managers need to strike a balance and overcome their differences. You might be one of those two managers, or you might be part of the senior management team, having to deal with managers who have conflicting views: "You versus you, and me," in a sense.

The most common you-and-me dilemma that can be found in almost every organization is between "me" and the rest of the company: local versus global—the choice between local optimization and corporate alignment. For instance, one business unit may introduce a product or service with high-growth potential that competes with a cash-cow product from another business unit. Think of the hardware vendor that sees the growth of the personal computer at the expense of large corporate mainframes. Or think of a savings account offered by the direct-banking division offering more interest than the standard full bank savings account that is connected to retail checking accounts. You may argue that it is better to cannibalize yourself than allowing the competition to do so, but your fellow manager in the other division is still not going to like it. Your success will cost him his bonus. Or think of corporate marketing banning one business unit's marketing campaign, as the target audience has been bombarded and exhausted already by other parts of the business. And what about the needs of a small and growing corporate startup unit, while the overall business has to deal with a hiring freeze? Come to think of it, the budgeting process is nothing other than battling a big dilemma: how to distribute the resources for the coming period across the various departments and business functions. Or consider serving a customer in one country while there are legal issues about that in other countries (such as the tobacco industry, weapons industry, or companies under investigation). Or the opposite: choosing to not serve a class of customers, although there is no legal basis to refuse such customers, such as legitimate businesses in the sex industry.

These are all examples of social dilemmas. A social dilemma can be defined as "a situation in which a group of persons must choose between maximizing selfish interests and maximizing collective interests." It is generally more profitable for each person to maximize selfish interests, but if all choose to maximize selfish interests, all are worse off than if all choose to maximize collective interests.[144] How do we make the right call?

It is impossible to look at you-and-me dilemmas without taking the ethical side of decision making into account. Morals (or ethics; the terms are often used interchangeably) form a code of conduct to refer to in judging what is right and what is wrong. Ethics revolve around three central concepts: self, good, and other.[145] You display ethical behavior when you do not merely consider what is good for yourself but also take into account what is good for others. This does not mean that you should be completely altruistic and always do good to others without considering your own needs. That is not sustainable. Moral dilemmas arise when the division between what is ethically right and wrong gets blurred.

The philosophers agree to disagree on what is morally right or wrong.[38] There can be two moral approaches to dealing with dilemmas.[146] The first school of thought defines morals as universally applicable (this is called the universalist approach, or ethical absolutism). Things simply are right or wrong. It is wrong to kill, it is wrong to lie, it is wrong to steal. In this way of thinking the consequences of doing the right thing are simply not relevant. It is always wrong to lie; abortion is always wrong; under no circumstances should you kill—even if there is a "greater good," such as saving many lives, or protecting many jobs. For people subscribing to this school of thought, dealing with a dilemma means finding out what is the right thing to do, and following through, no matter what—making the tough calls that come with the job. Some associate this style of thinking with Western culture; others have called it the "male way."

The other school of thought does not consider an act to be morally good or bad as such, but weighs the consequences in making that determination (called the consequentialist approach, or ethical relativism). In more formal terms, good and bad are not attributes of the subject at hand, but rather its context. Robin Hood stole from the rich, but did it to help the poor. A few years ago, a Roman Catholic bishop in my country stated in the press that it was not necessarily all bad for a poor person to steal bread if he were hungry. And sometimes it is necessary to sacrifice the needs of a few for the benefit of the many. Good things can come from bad decisions.

Subscribers to this school of thought will weigh their options when facing a dilemma in a different way. What makes a problem a dilemma is that all options have negative consequences. Choosing between them is not a preferred solution. There must be ways to satisfy everyone's needs and avoid negative consequences. Take care of the baker's trash and sweep the courtyard, and then ask for bread. Breaking your arm is not necessarily a bad thing, if you fall in love with the nurse in the hospital (and it is even better if she falls in love with you, too). The consequentialists might develop a more creative way of dealing with dilemmas, being more comfortable with ambiguity in decision making. After all, the consequences are known only after the decision has played out. This type of thinking is more associated with Asian cultures, and sometimes is called the "female approach." See Table 8.1, which compares these two approaches.

A dominant paradigm in philosophy today is postmodernism. It is accepted that there are different ways to define truth, and different ways to display moral behavior. Even if you are a universalist and believe in universally applicable morals, as a rational decision maker you should be able to accept that there may be others who hold different, conflicting views to be equally universally applicable. At least, you would recognize their equally persistent behavior. As not everyone will agree on what is right or wrong, there can be significant moral dissensus. For instance, some point out that the social responsibility of a company is to maximize its profits and that other use of resources factually is stealing from the shareholders. It should be up to the shareholders to decide what to do with the returns. Others reject that reasoning and point out the need for organizations to give something back to society. Morals change over time. The whole discussion around corporate social responsibility was not very prominent in the 1980s—it simply was not expected of large corporations. And perhaps, 10 years from now, the discussion will have completely died down again, and corporate social responsibility will have become an accepted standard set of behaviors.

Table 8.1. Universalism versus Consequentialism

Universalist Approach | Consequentialist Approach |

|---|---|

|

|

It is universalist moral dissensus that creates most of the you-and-me dilemmas. All involved parties insist on their view being the correct one. Their solution is good, and the other solution is bad. Because moral dissensus is a reality, it does not help much to purely analyze the you-and-me dilemma on the table. Universalists will not discover a different view of the world, as analysis will drive them to the conclusion that is dictated by their paradigm. And the analysis of the consequentialists will focus on what consequences they feel are acceptable, and most likely will also not look for an answer outside the options on the table. A different approach is needed.

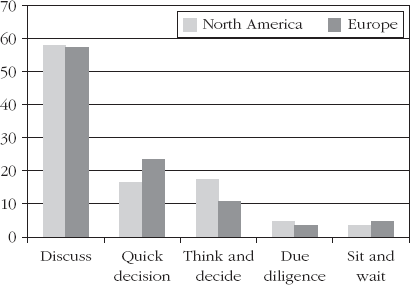

Different people have different ways of dealing with dilemmas, and there are some cultural differences, too. According to the Dealing with Dilemmas survey, there is a correlation between the decision style respondents have, and the biases they display in the six business dilemmas I described in Chapters 3 and 4. In addition to all the questions on how organizations deal with dilemmas, the survey also asked people about how they tackle dilemmas personally—their decision style. People who have a "sit-and-wait" attitude have a bias for the short term. Sometimes waiting for something to blow over is good, but not always. Knowing when to act and when not to act is key to stretching the strategy elastic in the long- and short-term dilemma. I discussed choosing the optimal decision moment in Chapter 6. Others see discussing the dilemmas with others purely as going through "due diligence." They tend to have a bias for leading instead of listening to customers. They also have a bias for inside-out thinking. This makes complete sense. Usually, they have the answer in mind already, and the rest is implementation. Finally, leaders who think long and hard before they make a decision—without consultation with many others—have a higher chance of bias toward a top-down approach, and have a long-term view.

Figure 8.1 shows that respondents from Europe tend to favor making a quick decision, and this percentage is much lower in North America (there were not enough responses from Asia to make a meaningful determination). The percentage of respondents who think long and hard,[39] and then decide, is much higher in North America. However, most respondents across the regions favor discussing the issue with others, to collect multiple opinions. This approach is central to successfully dealing with you-and-me dilemmas.

I have found three elements to be important in resolving you-and-me dilemmas.[40] These are elements, not steps, because all three of them may take place at the same time, and in the process of resolving the dilemma, you may revisit them multiple times. You need to (1) examine your motives, (2) communicate, and (3) try to reconcile the opposites.

The first element, whether you are a universalist or a consequentialist, is to realize that analyzing the options on the table may not always help you. The whole point of a dilemma is that it is pretty clear from the outset that each of the options has negative consequences, or that constraints keep you from doing everything that you need to do. A first analysis should point out whether you might be facing a false dilemma that in truth is an optimization problem, as I describe in Chapter 7. But once it is confirmed that you are dealing with a true dilemma, and particularly a you-and-me dilemma, additional analysis is merely going to confirm this more and more.

Instead of examining the options, dilemmas require a close examination of your own motives. Assume that you have to fire someone from the team, which is a difficult decision for most managers (and it should be). For many, this may form a dilemma, based on the implicit desire that most people have, which is to be seen as sympathetic, friendly, nice. You may have loyalty both to your firm and to the person on your team. Once you understand your desire to be thought nice, as a universalist you may, for instance, decide that this should not play a role in the decision you have to make, and the dilemma disappears. You have found the right choice for you. As a consequentialist, you may want to define what it means to be thought nice. Is it nice to not fire a person, but simply sidetrack him or her, and never provide the feedback that this person has no future in this company? That is the consequence of not firing this person. Or is it perhaps nicer to the rest of your team to fire this person, as the team is suffering from a lack of performance and productivity because of the whole situation? You may still not like firing this person, but your desire to be thought nice actually tells you what is the right thing to do as well.

In many cases, the solution to a problem comes to mind immediately. You need to buy a bigger car (if only you had the money), you need to invest in a certain technology (you are lagging behind the competition already), or you need to start discounting (as the economy is turning bad and demand is collapsing). Examining your own motives and thinking process may uncover the fact that you jumped to conclusions, that it is time to take a step back and look for alternatives, and that it does not have to be an either/or choice. Maybe a bigger car is not needed, as—once you think about it—you would need the extra capacity only a few times per year, and renting a car for those occasions might be much cheaper. And perhaps it is smart to wait a little longer and invest in the next generation of technology, leapfrogging the competition. And is discounting really the best option to keep demand up? Perhaps you can unbundle the product and sell a basic product at a lower price while adding services to upsell.

Dilemmas are full of emotion. We feel we are put on the spot, and that the situation is not under control. Anger, frustration, fear, and anxiety may all be part of the mix when you are confronted with a you-and-me dilemma. Why is there always someone who does not agree with you? Why can't people simply do what you want for once? Why is it always he or she who is such a negative influence? And in the heat of the fight we can confront others (or be confronted) with a sucker's dilemma: "My way or the highway." Did you really mean to say that? Would you not rather find a common denominator than escalate? The old advice to count to ten before responding might not be a bad idea. All too often we regret words spoken to air our emotions, instead of asking ourselves what it is we are trying to achieve—take a firmly entrenched position, or build a bridge? Examining your motives is the start of successfully dealing with a you-and-me dilemma, as the dilemma might say more about you than about the actual tough choice to be made.

This goes for organizations as much as it goes for people. An organization faces dilemmas all the time, being confronted with conflicting stakeholder requirements.[41] Dealing with stakeholder dilemmas starts with self-reflection, too. What is it your organization is trying to achieve? How can profit and value be reconciled? What is it that stakeholders expect from us, and what contributions do we expect from them? How can we align these contributions and requirements? If we spend more time discussing how to spin a strategy to the market than actually rolling it out, we are setting ourselves up for many dilemmas of the ugly kind. Without self-reflection, open communication, and reconciliation, there is no hope of improving our strategy elastic.

The second element is to make sure that the parties involved communicate. In most cases, when people state their position regarding a certain problem, they will state their solution to their side of the problem. In Chapter 1, I described Western management culture with a few statements, such as "If you are not part of the solution, you are part of the problem." However, this attitude creates dilemmas instead of preventing or solving them. When dealing with dilemmas, it is important to discuss the problem first. In other words, if you are not part of the problem, you are also not part of the solution. The solution comes from seeing things from multiple perspectives. By being part of the solution from the start, the only angle you will see is your own.

We all know many examples of this. "This sales assistant has to go, because he or she is just not performing," or "We need stricter laws in place to make sure this type of accident will never happen again," or "We need to change the price of the product, as our competition is beating us." Immediate solution orientation creates the dilemma. Different solutions are compared, and the underlying problem is forgotten. Even worse, the moment another party has a different, opposite opinion, emotions flare up again. People may reject the idea of being part of a dilemma at first; they will probably tell you that as far as they are concerned, there is no other choice but to see their side—an ultimatum.[42] How can someone not see the problem, particularly when the solution is so obvious? It takes professionalism to also listen to the other side: "The sales assistant should not go—he or she has other very important qualities," "There is a country-wide initiative in place to actually decrease the number of laws," or "We cannot lower the price of the product; otherwise it is not profitable anymore." Acknowledging there are multiple sides to the story, even if you do not agree, is the key to reconciliation. The key to these conflicting positions, which are posing a dilemma, is to figure out the actual problem underlying the presented solution. Perhaps the problem with the sales assistant not performing is that he does not communicate very well with customers, but he never makes a mistake with complex offers and revenue recognition. A position in sales operations would be better. And regarding the accident, in the end we do not want more rules; we just do not want accidents to happen again. Are there other ways of prevention? And, there are many ways to compete; how is the competition beating us? By asking questions, we uncover not the proposed solution to the single-sided problem, but the actual problem. Comparing proposed solutions leads to a you-or-me dilemma; a common understanding of the problem is halfway to a you-and-me solution.

A powerful way to reconcile a dilemma is to find a way to switch roles. This works in cases where people know they need to find a way to work together; the dilemma is that they have seemingly irreconcilable differences on how to do that. For instance, think of a newly formed management team of two merged companies, each based in very different corporate cultures. They have to find a way to make it work. Or think of a coalition of two political parties that need to collaborate to form a majority government. Despite different opposing views, and the election battle that has been going on, they need to find a way to come to a program, and a fair division of ministerial posts. Switching roles requires creating an environment of trust in which you ask the people involved not to talk about their own convictions, but to talk about the convictions of the other side—in other words, to defend their opponent's point of view. This not only helps in understanding the position of others, but also triggers examination of your own preconceptions.

If this is not possible, at least make sure all involved parties openly discuss their opposing views, and more important, what they are based on. Are they based on past experiences (but times have changed), religious beliefs (that may not belong in the workplace), or personal goals (which could be reconciled with the goals of the other parties involved)?

In fact, communication is also the key to solving the prisoner's dilemma that I referred to in Chapter 1. Recall the situation: Two suspects are being charged for a crime and offered a deal, independently of each other. If both remain silent, they will be charged with a lesser crime and will each receive a short sentence, one year in prison. If they both confess, they will each receive a longer sentence, five years in prison. If one confesses and the other remains silent, the one who confesses will be released, and the other will be sentenced to ten years in jail. They cannot talk with each other. Although the best solution for both would be to remain silent, the fact that they are not able to talk it over means that most likely both will talk, each hoping that the other does not. The result is five years in prison, instead of only one year. Communication during the arrest is indeed not possible, but it is possible beforehand. In fact, criminal organizations such as gangs and mafia invest quite a bit of time building strong relationships based on motivation and communication. Belonging to the organization is like being part of a family, with a very strong sense of loyalty. The rules of engagement are very clearly communicated, in word and in deed. For members of the organization, it is clear that talking may lead to a shorter jail sentence, but will have negative consequences for the suspect after the jail sentence, and perhaps immediate consequences for family and friendships. At the same time, not talking to the police is rewarded handsomely. The organization takes care of the suspect's loved ones during jail time.

Most organizations have a very well-developed hierarchy, with objectives, clear responsibilities, and a high degree of accountability. Managers all report up into the organization to their managers, until the consolidated results reach the executive team. This structure is the cause of many strategic dilemmas. The back office has different objectives than the front office, but has—through the management structure—no insight into what the front office really does. It is a different set of responsibilities. Vertical management structures with mutually exclusive domains and responsibilities do not invite managers to openly discuss their problems, other than in the executive team. Even if managers wanted to discuss problems, exploring multiple angles, there would not be a logical structure to do so—except, of course, when it is too late and a "multidisciplinary taskforce" is instituted to fix what has gone wrong.[43] Alignment does not have to be vertical. Alignment can also be horizontal, where managers are required to optimize the work across the whole value chain, instead of just within their own unit. In addition to business domains, organizations need to define their business interfaces.[44] A business interface is where work gets handed off between one system and the next, between one activity and another, between one process and the next, between one department and another. Business interfaces need to be managed as conscientiously as do business domains.

Together with self-reflection and communication, reconciliation forms the third element. Can you find a way to bring the opposite sides together? Figure out how to achieve both goals at the same time? Realize that you want the same thing, just in a different way?

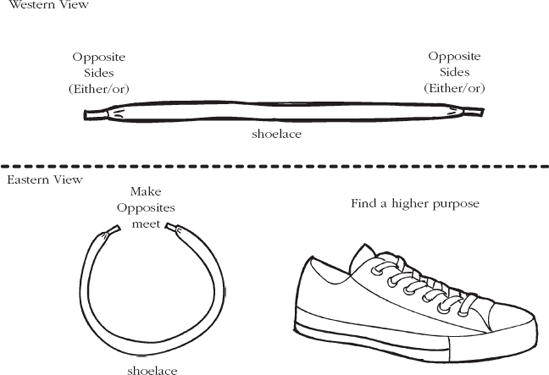

The Western way of thinking does not make it easy to answer these questions, as we tend to see the different sides of a dilemma as mutually excluding opposites—either/or thinking (see Figure 8.2). Figure 8.2 also visualizes a more Eastern point of view, where opposites are alike. For instance, love and hate are very similar emotions.[45] From a business perspective, different people may have different solutions for a certain problem or strategic direction, but after examining their motives and discussing them, they come to the conclusion that they want the same thing: to be successful. If one executive is looking to acquire a certain company, to get access to a particular market or technology, while another executive is opposed to the acquisition because of the risks involved, these two opposites could be bridged by starting a joint venture or another type of partnership between the two companies.

Or consider the different schools of strategy, as discussed in Chapter 2. One group of people claims that structure follows strategy. The strategy comes first, and the organization should adapt to that strategy. A new strategy therefore often requires reorganization. Another group of people would claim the opposite: Strategy follows structure. Strategies are put together by existing structures and it is unlikely that thinking from such a structure can be seen as independent from that structure. But are these really opposites? Both points of view can be easily combined. Strategy and structure are interdependent. Strategies are formed by a structure, and based on strategic feedback that structure may be changed, leading to an adapted strategy, leading to . . ., and so on.

Another example comes from the field of intercultural management.[147] For global organizations there is always a dilemma between creating a global corporate culture and creating space for local national cultures. The effects of this dilemma can be found in something as simple as the use of the word yes. According to one local culture, it can be very impolite to say no, whereas in another country's culture, it is equally impolite to say yes without following up on it. Still, reconciling such cultural dilemmas can be as fundamental as aiming to create a culture that celebrates diversity.

As an alternative to connecting both opposites, you can try to find a higher objective. You could discuss among fellow board members the necessity of firing a high-performing CEO because you fundamentally disagree with his views on life and the political statements that he aired in a high-profile business magazine. But freedom of speech may be an even higher goal, as in the Voltaire paradox: "I despise what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it."

On a larger scale, consider one of the core dilemmas in the tobacco industry. As smoking poses a health risk, should this industry simply stop its business? Is it morally defensible for a responsible company to sell products that are unhealthful and addictive? And even under all current regulations and restrictions, could you call producing and selling tobacco a responsible business? But what is the alternative? People have been smoking various things since the beginning of time, and simply not producing and selling cigarettes anymore is not going to take away the demand. Is the alternative to leave the business in the hands of less responsible companies, effectively letting the market go underground? It seems the tobacco industry is complying with all regulations in trying to protect its business. Fundamentally, the dilemma is not addressed, at least not visibly to the general public. The higher objective is to answer the key question of what happens next. What comes after cigarettes? Would that be nicotine sticks or nicotine chewing gum? Would it be nicotine- and tar-free cigarettes, or something else? As long as the tobacco industry is looking to reinvent itself—Tobacco 2.0—the industry is on its way to reconciling its dilemma, to creating a synthesis. Yes, its business is unhealthful, yet the players show their sense of responsibility by actively trying to change their product.

In Chapter 1, I discussed thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. The thesis represented a certain situation that suffers from a dominant disadvantage, that is being addressed by a reaction, the antithesis. However, the antithesis probably displays the opposite dominant disadvantage. The synthesis then combines the best of two worlds. As one of those little ironies of life, the synthesis becomes the new thesis. The "best of both worlds" seems to have some disadvantages as well, and these will be addressed by an antithesis, and ultimately a new synthesis—a potentially endless cycle. Take, for instance, the example of the joint venture as the synthesis between acquiring or not acquiring a certain company. The joint venture combined getting access to a certain market or technology while at the same time not significantly increasing strategic or financial risk. But the disadvantage of this joint venture might be in not having the same market power as both its parents have, or in having less access to corporate resources. A reaction will occur eventually. Or consider the tobacco industry that shows its responsibility by investing its profits in a new generation of products that do not have such adverse health effects. How can it do that in a responsible way if there is no certainty of the demand for such new products? The tobacco company also needs to be responsible toward its employees, and other stakeholders such as its investors. Reconciling one dilemma usually reveals yet another. Dealing with you-and-me dilemmas is a continuous process of synthesis.

Phenomena and events in the real world do not always fit a linear model. Hence the most reliable means of dissecting a situation into its constituent parts and reassembling them in the desired pattern is not a step-by-step methodology such as systems analysis. Rather, it is that ultimate nonlinear thinking tool, the human brain. True strategic thinking thus contrasts sharply with the conventional mechanical systems approach based on linear thinking. But it also contrasts with the approach that stakes everything on intuition, reaching conclusions without any real breakdown or analysis.[148]

One of the most important characteristics of a successful strategy is that it distinguishes the company from its competitors. Clearly, this calls for lateral thinking and a creative approach. But as Ohmae remarks, strategic decision making is more than a seat-of-the-pants approach based on experience and intuition, or an advanced form of art. The same is the case in dealing with dilemmas. Although perhaps not linear, there is logic to it. And although creative in nature, there is a process.

Manufacturing is known for its focus on continuous improvement. Lean and Six Sigma are perhaps the two best-known approaches.

According to the DwD survey, around 50% of organizations use them in some form. However, there is another methodology that I think is even more fundamental, called theory of constraints (TOC).[149] Unfortunately, TOC is not very well known. The DwD survey shows around 2% of organizations have it in their standard toolkit. A third of respondents have never heard of it, and an additional 40% claims to have heard of it but are not using it. In addition to ways of creating continuous improvement, it introduces a way of arriving at performance breakthroughs. The original author, Eliyahu Goldratt, dramatically refers to it as "evaporating clouds"[150] others prefer a more business-oriented term: conflict resolution diagrams.[151] Define a problem precisely and you are halfway to a solution, is the promise of a conflict resolution diagram.

As in every continuous improvement methodology, conflict resolution diagrams work their way backward, with the end in mind. The goal must be identified first. This helps us to create a synthesis or reconciliation between the advantages of both strategies. Other than trying to optimize for one side of the dilemma, followed by the pendulum swinging to optimizing the other side, conflict resolution diagrams help questioning the requirements and prerequisites to see if the problem itself can be eliminated. Perhaps we have chosen the wrong goal. First, we decompose the choices on the table into smaller choices. Then we start to recompose those choices, into a single picture or into a new strategy, thus avoiding an either/or choice.

Although originally implemented in manufacturing environments for improving throughput, decreasing operating expenses, and lowering inventory, conflict resolution diagrams can also be used for dealing with dilemmas. In Chapter 3, I identified three fundamental intraorganizational you-and-me dilemmas. Value and profit, outside in and inside out, and top down and bottom up. Let us discuss a number of these dilemmas using the conflict resolution diagrams.

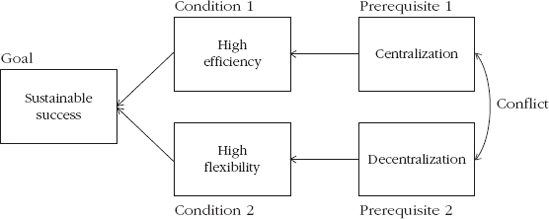

On one hand, organizations should be managed top down. Strategic objectives have to be set, and the organization has to adjust. On the other hand, organizations require a bottom-up approach, where we look for ways to get the most out of the resources we currently have. As a result, organizations go through a continuous cycle of centralization and decentralization. For instance, once in a while, organizations have to fix their cost structure, because growth has led to cost control issues. The logical solution is to centralize functions in the organization, a top-down approach. Control is increased, economies of scale are reached, and as a result costs go down. The organization is now more efficient. A centralized environment also has some disadvantages. The decision power is unnecessarily far removed from operations and concrete market opportunities, inhibiting growth. This means middle management should be empowered to make their own decisions and find their own solutions to deal with opportunities and problems. This leads to a more decentralized environment, a bottom-up approach. After a while, however, this leads to cost inefficiencies, and the pendulum swings again. The thesis of centralization leads to the antithesis of decentralization, and vice versa.

In a conflict resolution diagram, the dilemma would look like Figure 8.3.

Let us decompose both the centralization and decentralization strategies (see Table 8.2).

Table 8.2. Dilemma Decomposition

Centralization | Decentralization |

|---|---|

Source: Adapted from B. Johnson, Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems, RD Press, 1992. | |

+ | + |

|

|

|

|

|

|

− | − |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Centralization and decentralization seem to be mutually exclusive. The advantages of one are the disadvantages of the other. How can we be in control and flexible at the same time? How can we focus on economies of scale and keep a focus on the needs of specific markets? How can we empower people to make their own decisions, and maintain uniformity?

This last question gives the first clue as to how to reconcile. How to maintain uniformity, while empowering people. That is what a standard does. A standard is a uniform approach for people to apply in different situation. Standards also offer economies of scale, as everyone is working in the same way. Best practices can be developed and shared across the various functions of the organization. Standards do not take away focus from specific markets; they are simply applied differently. Once you have strong standards in place, it does not matter anymore whether you are centralized or decentralized. We have created a higher level of understanding—we have achieved synthesis.

Standardization represents the synthesis, combining the thesis and antithesis of centralization and decentralization. Once the standardization is in place, it represents the new situation, in other words, the new thesis. The challenge in a standardized environment is how to handle exceptions, and how to deal with the innovation that so often comes from diversity. Once this becomes problematic, this will lead to an antithesis, solving the exceptions problem, but compromising the standardization. Another synthesis will be needed.

If you treat business as a zero-sum game, in which your profit automatically means someone else's loss, there will always be a dilemma. The key is to define value for the customer that is profitable for yourself and all others in the value chain. Perhaps one of the best examples comes from the Apple iPod mp3 player. The product itself may have had a stunning design over the various generations, but the device itself is not the key innovation.[46] It was not the first mp3 player on the market, most of the materials are freely available on the market, and with the exception of the user interface, most functionality is not unique. The key innovation is in the business model,[152] reconciling an important dilemma.

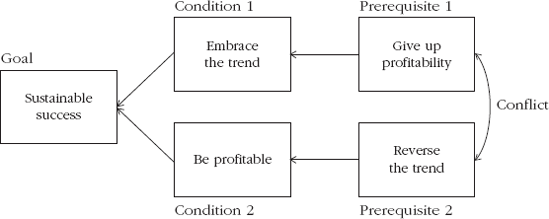

Before the music store that is part of the Apple iTunes software, mp3 files were very much associated with illegal downloads. However, downloading music as mp3 files ("rip, mix, and burn" as Apple called it) is the way forward, the future. Despite various legal procedures by musicians and music companies (remember Napster?), the popularity of downloading mp3 files could not be denied. The music industry was in danger. The profitability of the industry was in the declining model of selling CDs, physical products with a fixed number of tracks in a fixed order. This is a clear strategic dilemma: embracing a future that consists of an unprofitable business model (how to compete with "free"?) versus unprofitable prospects of the current business model. The conflict resolution diagram could look like Figure 8.4.

This is the classic you-and-me dilemma. The customer value conflicts with the music industry's profitability. Let us explore this further by decomposing the options (see Table 8.3).

Table 8.3 shows that the disadvantages of embracing the trend and sticking to the old model at least outnumber the advantages. It is hard to cannibalize your own business model if you do not know whether the new business model is going to be successful. This is a very clear case of being in the eye of ambiguity between two S-curves, as described in Chapter 6. And the choices seem to be completely mutually exclusive. The advantages of one are the exact disadvantages of the other.

Table 8.3. Dilemma Decomposition, Value and Profit

Embrace the Trend | Be profitable |

|---|---|

+ | + |

|

|

| |

| |

− | − |

|

|

|

|

|

But let us question the assumptions. Do we really have to reverse the trend to keep up profitability? Is there no way to compete with downloading music for free, and make that profitable? Apple understood that the "free" model was not without disadvantages as well. The quality of the downloaded mp3 files was far from guaranteed, and it was quite a hassle to convert those mp3 files to an mp3 player, using different types of software that often felt like an afterthought. Apple, with a strong reputation for alignment of hardware and software, solved that problem: perfect integration of downloading and managing music with its iTunes software from a demand chain point of view, and a high availability of music through distribution contracts from a supply chain point of view. Distribution and integration: This was enough to justify asking users for the modest price of less than one dollar per track. Value and profit go hand in hand.

That leaves the issue of the strategic risk of not getting it right. Obviously, strategic risk cannot be avoided completely. There is always a chance that the chosen direction or the product solution will not pan out the way it was intended. But here is where the win-win approach of the you-and-me dilemma starts to work. The Apple iPod is not only Apple's success. Myriad partners offering accessories are part of the success and share in the success, and the same goes for the music companies. This risk is distributed, but with so many parties involved, the chances of success have been maximized.

In the meantime, the entire music industry has changed, and is building a new S-curve. Artists have had to reexamine their sources of income. Concerts, not CDs, are now in many cases the main source of income. As a result, fans get to see the artists more. The balance of power is changing. In October 2007, Madonna signed a new deal not with a major record company, but with LiveNation, a concert promoter.[153] Hip-hop legend Jay-Z and rock band U2 did the same in 2008.[154] Prince gave away his new CD in the Sunday edition of the UK newspaper Mail to promote his series of concerts in the London O2 stadium.[155]

Even the traditional business of selling CDs has changed. There are hardly any CD stores left in shopping malls and on the streets—sales have moved online. Current stores focus more on DVDs and games. But it stands to reason that the same thing that happened with CDs will happen to all forms of information not stored in an openly accessible way. What happened to Napster enabling downloading mp3 files has now also happened to web sites such as The Pirate Bay enabling sharing of complete movies. Newspapers struggle with a declining subscription base, and authors putting their books online for free sometimes actually see an uptick in traditional sales. Games are moving online as well, and advertising is becoming a more important source of income for game studios. Value and profit are realigning.

[37] Quotes taken from an interview with Mr. Dick Berlijn, combined with D.L. Berlijn, No Guts, No Glory, NRC Focus, Netherlands, March 2009.

[38] In fact, the philosophers have found their own synthesis in this discussion, and address this as meta-ethics, understanding that there are multiple ways of deciding what is ethical behavior in the first place.

[39] Or, as one respondent called it, "Go for a ride on my bike."

[40] I do realize that this is a rather universalist remark. I am prescribing three universal keys here that lead to the right answer. But I would like to point out there is a greater good here, a higher motive, which is getting my point across without getting it blurred by too much subtle discourse. Of course, it depends on many things, but the three keys certainly help. This footnote reconciles my dilemma, unfortunately, by compromise: making a strong point (main text) while at the same time trying to provide a subtler view here in the footnote.

[41] I describe stakeholder dilemmas in greater detail in Chapter 10.

[42] An ultimatum poses a dilemma in itself, regardless of any other side to the dilemma. If you give in to an ultimatum, you decide based on pressure instead of trying to solve the problem. And if you do not give in to an ultimatum, the threat might be carried out.

[43] The sad thing is that instituting taskforces like this is being seen as decisive action, whereas in essence it is an example of "too little, too late. "Too late, because the damage is done; too little, because the structure that actually caused the problem most likely will not be changed. Any reorganization coming out of exercises like this is bound to be equally vertically structured. The pendulum swings and the organization sets itself up for yet another set of dilemmas.

[44] There is more on business interfaces in F.A. Buytendijk, Performance Leadership, McGraw-Hill, 2008.

[45] So the opposite of love and hate would be indifference.

[46] It should be said that Apple goes out of its way to cannibalize itself with new designs, new functionality, and new convergence areas, such as the iPhone, to keep a product lead. The new iPad is another example. The functionality of the product is not special, in fact, it is criticized for lacking certain functionality. The innovation is in offering a platform for mobile applications, unlocking new creative ideas for working and leisure that don't even exist today.