Strategy formulation is often seen as a somewhat mystic process. Heroic stories in the business press do not make it easier. They typically like to portray business leaders as geniuses with brains the size of a basketball who can see things that others cannot. At a crucial moment in time, they make a strategic call that turns out to make all the difference in business performance ever after, leading the competition by years. But the higher these leaders rise in the eyes of the public, the harder they can fall, in case their prediction did not come true. And there are severe consequences for the share price.

The press loves to write about brilliant CEOs such as Steve Jobs of Apple (although in earlier times this was very different), Wendelin Wiedeking of Porsche (until the debt grew out of control), and Fred Goodwin of Royal Bank of scotland (until the credit crunch came along). And we love to hear and believe these stories. Even managers and leaders working within an organization find the strategy formulation process nebulous. Once a year, the executives organize an off-site and gather for a few days. To the rest of the organization it is unclear what they are doing. Perhaps they sing secret songs around the campfire. And once the off-site is over, the executives communicate the new strategy to the organization. As it is unclear where it comes from, and even more opaque as to how to implement the new strategy, business as usual goes on. Eighty-five percent of leadership teams spend less than one hour per month discussing strategy, so it is no wonder that 90% of well-formulated strategies fail due to poor execution.[73]

Strategy formulation is not a very well understood process. In fact, strategy is not a very well understood term. It is amazing to see how such a foundational concept is not clearly defined. Most people would intuitively define strategy as making the big choices that matter, the decisions that set the direction of the company.

With this idea of strategy in mind, perhaps the perception that strategy is about "bet-the-farm" choices and decisions actually create many of the strategic dilemmas. And perhaps the traditional processes to formulate strategy add to that perception. Possibly, strategic thinking itself may lead to what Jim Collins calls the "tyranny of the or." A different vision on what constitutes strategy might prevent many dilemmas from even appearing.

In short, a strategy is an action plan to achieve the organization's long-term goals. More formally, it is a pattern of decisions in a company that determines and reveals its objectives, purposes, or goals, produces the principal policies and plans for achieving those goals, and defines the range of business the company is to pursue.[74] The three key questions that need to be answered for such a plan are: where your company is today, where you would like it to be, and how you think you will get there.

Peter Drucker refers to the theory of the business, which consists of the assumptions about the environment of the organization (society, the market, the customer, and, for instance, technology), the assumptions about the specific mission of the company (how it achieves meaningful results and makes a difference), and the assumptions about the core competencies (where the organization must excel to achieve and maintain leadership).[75] This definition is also fairly straightforward: What does my environment expect, what are we good at, and how do we match up those two? From here it becomes fuzzy. Mintzberg even introduces multiple definitions of strategy, the five Ps.[76] So we know already that strategy is about a plan, which is considered the way forward. For instance, it can be our strategy to become the cost leader in our market, to reach our goal of sustained business performance. Mintzberg adds strategy as a pattern, which is consistency in behavior over time. Think of Rolls-Royce, which has been known for many years for its high-end luxury cars. Strategy is also a position, introducing and maintaining particular products in particular markets, like Nike entering and dominating the market in various sports, such as soccer and golf. Strategy is also a perspective, the understanding of the executives of the market and their organization (like in Drucker's definition). Mintzberg ends with strategy as a ploy, a specific maneuver to outwit a competitor, such as acquiring a certain company, or even lobbying for a law that favors your company.

None of these definitions imply that strategy is about making big choices. All these definitions simply suggest views on how to make market demand and supply meet in the most favorable circumstances for your company. It is Michael Porter, one of the world's most recognized strategy experts, who stresses the importance of making choices. Porter defines strategy as the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a set of activities that is different from rivals.[77] Two elements are critical to this definition. First, a strategy needs to differentiate a company from others. Second, strategy involves making choices. Strategy is very much about what not to do, and requires trade-offs. Porter elaborately describes these trade-offs. Companies should choose a consistent set of activities that fit their image and credibility. For instance, Unilever's reputation would be damaged if it were to go into the tobacco business. Different activities also require different resources and competencies that may be hard to build up. For instance, extending your position as upper-class kitchen supplier to being a leader in interior design requires different skills, different suppliers, a different sales approach, and so forth. But most important, companies that avoid choices and lack trade-offs become stuck in the middle, do not differentiate, and cannot sustain.

Porter even warns against "popular management thinkers" claiming trade-offs are not needed, and dismisses the thought as a half-truth. The bit that is half true is that trade-offs are not necessary when the company is behind in the "productivity frontier" or when the frontier is pushed out. According to Porter, the productivity frontier is the sum of all existing best practices at any given time or the maximum value that a company can create at a given cost, using the best available technologies, skills, management techniques, and purchased inputs. Not operating on the productivity frontier means you are not leveraging your assets well enough. For instance, if the cost structure has not been optimized, if there is room for improvement in the quality of products and services, and if the business pace is below par, indeed all three can be optimized at the same time, and no choices between cost, quality, and speed have to be made. That situation is to be avoided, anyway. As many organizations have not reached their productivity frontier yet, it is easier to simply follow the market and copy what the competition is doing. In these situations, making no choices may even be preferred to risking blame for a bad decision.

This all may sound logical, but let us argue with Porter a bit. "Stuck in the middle" sounds like a compromise. A compromise means meeting in the middle. Arguably, this is where most companies are, as per definition there can be only a few leaders. However, it is not a desirable place for those who want to outperform their competition. Dealing with opposites does not always have to lead to either a compromise or an either/or choice. Jim Collins referred to this as the tyranny of the or, and pointed to the genius of the and as a better approach, embracing both extremes. If you want to move from "good" to "great," Collins points out, you should not too quickly accept that avoiding making choices leads to being stuck in the middle. There might be less linear and analytical and more lateral and creative ways of thinking.

Further, it is generally accepted that strategy should ensure a company's future success, plotting the steps toward the goal. And if there is one thing we know about the future, it is that it will most likely be different from today. How are we supposed to make the right choices today that impact tomorrow's performance? And is it wise to make choices that will limit our flexibility to respond to tomorrow's needs? Do we really believe that with analytical rigor we can foresee the future? That if we have all the data and are smart enough, we can crack the code? Of course not; that is not the question. The real issue is how to deal with the unknown future. Sure, to a certain extent we are the architects of our own future, but strategic uncertainty is a given, and your choices will either turn out to have been effective, or not. Strategy has to align itself to the fluid nature of the external environment. It must be flexible enough to change constantly and to adapt to outside and internal conditions.[78]

What happens if we do not think of strategy as making choices and commitments, but rather as creating a portfolio of options?[79] Options, as opposed to choices, do not limit our flexibility in the future; they create strategic flexibility. You can compare strategic options to stock options. Stock options give you the opportunity to buy shares at a certain price, but you can choose when this is (within a period of time), and you do not have to. Strategy as a portfolio of options behaves the same. It gives you the opportunity to exercise these options in the future, but you do not have to. Options allow you to make a relatively small investment now, with the opportunity to make bigger investments later, when you have more or better information. In short, options enable you to wait until the moment is right. Obviously these options should not be random—they should be structured around strategic themes, such as growth based on acquisitions, or organic growth, or themes such as creating a greener way of working, entering or retreating from certain markets, or specific go-to-market strategies.

The concept of options in the real world, as opposed to options as a financial instrument, is called, not surprisingly, real options.[80] Examples could include investing in university relationships, having a finger on the pulse of possible future innovation. Or it may consist of implementing an open IT architecture, to be ready for future software requirements. Or think of not immediately terminating a nonprofitable customer relationship and invest in it for a while, there might be alternative ways of improving profitability.

In the traditional view, risk and uncertainty depress the value of an investment. If you focus, not on making bet-the-farm choices, but on creating managerial flexibility, risk actually becomes an instrument for value creation. Uncertainty, seen this way, does not depress the value of any investment, but may amplify the value of investments. Strategy, with its focus on the future, is characterized by uncertainty. The more uncertain a future is, the more having flexibility and adaptiveness as a core strategic competence is worth. Defining strategy as creating options for the future allows you to take on riskier investments that have a potentially higher upside, for the same risk appetite an organization may have. Or alternatively, they allow you to lower the risk of your current profile, as you can still opt-out from subsequent investments.

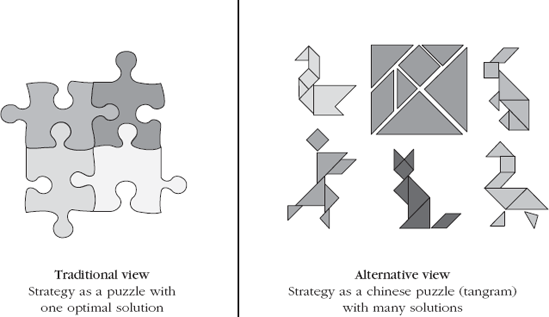

If you see strategy as creating a portfolio of options, there is no "single best strategy." Let us use the metaphor of a puzzle. Strategy is often seen as a traditional puzzle. Each puzzle piece is a part of the strategy. External factors, such as competition, market conditions, regulations, and value chain constraints, are puzzle pieces, as well as internal factors such as resources, capabilities, culture, and expectations. And the idea is to find out how to combine all the puzzle pieces into one single "big picture."

The alternative view, strategy as a portfolio of options, looks much more like a tangram,[81] a Chinese puzzle. It consists of seven pieces—five triangles, one square, and one parallelogram—and it can be used to create many pictures. The right-hand side of Figure 2.1 shows some examples, such as a dancer, a cat, and a rabbit.

The idea is not as esoteric as it sounds. In fact, it is already practiced in a number of areas. Financial institutions are moving to a strategy of product components and half-products, instead of off-the-shelf standard products. Based on the customer risk profile or specific customer requirements, financial product components can be combined into a uniquely tailored product. Some mortgages may involve investment components, and others not. Financing objects may be a combination of leasing, loans, and other instruments. And in an ideal case, not all components even have to come from the same financial services institution. A platform of compatible product components has been created to construct product configurations that you had not even thought of before. Because of the upfront investment in a portfolio of product options, there are no dilemmas as to which products to introduce and which not. The idea of having a platform is very common also in the automotive industry. A single car chassis is often shared among multiple models, sometimes even spanning multiple brands. An extreme case involves the Toyota Aygo, Citroen C1, and Peugeot 107, all of which share not only the same chassis, but also the same engine.

Using the principles of a portfolio of options, the software industry is currently undergoing a paradigm shift, adopting what is called service-oriented architectures. In these architectures, pieces with a well-described set of single functionality are called components. Systems can be constructed, deconstructed, and reconstructed using multiple components. An example of a component could be a piece of functionality that supplies all address details when it is called by a system that "knows" only the customer number. Or think of a component that assesses the risk of a claim in an insurance company and returns a recommendation whether to involve a damage assessor or not. All of these components have to be built only once, and can be used many different times. As long as they fit in the same "component-based framework," components can come from different developers and different firms. The idea of a service-oriented architecture has a huge impact on how to build a systems landscape. Moreover, it has an equal or even bigger impact on organizational strategy. Systems are all too often barriers to change, and traditionally may not even support the organizational agility implied by a portfolio of strategic options.

The idea of strategy creating options does not conflict at all with the established definitions of strategy. It supports the definition of strategy as a plan of action designed to achieve a particular goal. The goal stays the same; the plan of action just becomes clearer over time. It is the same with the definition of strategy as understanding where you are now, where you would like to be, and how you will get there. The details will unfold while on the road, avoiding unexpected roadblocks and discovering previously unknown shortcuts. In fact, the idea of strategic options even supports Porter's definition by turning his thought about the productivity frontier around. Porter states that the only situation in which you are not required to make choices is when you are not operating on the productivity border, in other words, when you are below par on cost, quality, and speed. What if you find ways to continuously push out that border, so that you are not required to make choices that others would have to make? That would be a source of competitive advantage. In addition, your superior ability to create options and utilize opportunities can also be a source of differentiation.

This does not mean you do not have to have a strategy, and you jump on every opportunity. Creating options does not equal opportunistic behavior, jumping on every profit-making activity that comes along. The strategic goals still need to be clear. We need to ensure we make it to our goal, and at the same time do this in an efficient manner. Some options help us reach the goal; others detract from that focus. It is merely the way the strategy formulation process is structured and how the strategy is described that are different. Traditionally, formal strategy and planning implies setting positions, targets, and measures. Alignment means follow the leader. Assets are allocated based on forecasts that are expected to hit their targets. Instead, I would like to propose a different view on alignment, where organizational learning is emphasized as well as being prepared for whatever conditions may arise. Alignment means learn and collaborate.

Does all this sound too much like "postponing thinking," going with the flow, and being reactive to change? On the contrary; I would say it requires much deeper thinking than traditional strategy formulation, as it requires uncovering the deeper truth of what Drucker called the theory of the business. The theory of the business is a strategic framework. The strategic framework describes our assumptions about the environment of the organization (society, the market, the customer, and, for instance, technology), the assumptions about the specific mission of the company (how it achieves meaningful results and makes a difference), and the assumptions about the core competencies (where the organization must excel to achieve and maintain leadership). In laymen's terms, the word theory perhaps sounds static, but theory means nothing else than "the best possible understanding of reality we have." And in business that is a highly dynamic process.

In the traditional sense, once choices are made and a strategy is implemented to move forward, usually the assumptions are forgotten. The choices and the strategy become hard truths. "We aim to be an operationally excellent company" or "we differentiate based on superior service" make us forget to look outside and see if this is still what is expected from us, or what we are recognized for, or if by industry standards we still live up to our claim. By investing the time to create a strategic framework describing the theory of the business, we keep track of our assumptions and can road-test them continuously. While the goal (that we chose) remains intact, and the assumptions remain in place as long as they match reality, we can travel toward our goal, assessing whether options that we create and opportunities that we see fit into the framework. If so, we capitalize on them; if not, we let them go. And the moment assumptions change, we can immediately see which activities do not lead us to the goal anymore, or which activities are lacking in making it to the goal. Choices do not turn into dilemmas.

Still, the idea of strategy being about making tough choices is deeply entrenched in today's best practices. We will further explore this, and what to do about it, examining three dimensions: strategy content, strategy process, and strategy context.[82]

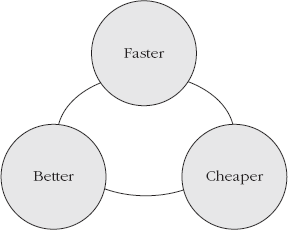

"Strategy is about making choices, and there are only so many choices you can make." This is what the strategy textbooks teach. "The number of ways you can differentiate is limited and you cannot have it all." I recall seeing a sign in a shoemaker's shop, "We can do things quick, cheap, and well. Pick two." (See Figure 2.2.)

This seems to make perfect sense. If the shoemaker is asked to mend a pair of shoes quickly and well, it will not be cheap since he will have to drop everything else in order to repair that one pair of shoes. The shoemaker can then charge a premium. If the work needs to be done quickly and cheaply, the shoemaker will ask his apprentice to do the job, and thus the repair will not cost as much. The third option is for the shoes to be done well and cheap, which means it will have to wait. But you cannot have all three at the same time. This thought is also deeply embedded in strategy best practices. Again, we need to look at Porter, who defined three generic strategies: cost leadership, differentiation, and market segmentation (or focus).[83] The work that Treacy and Wiersema did regarding what they call value disciplines is very similar.[84] They speak of operational excellence, product leadership or product innovation, and customer intimacy. Organizations need to be sufficient in all disciplines, but excel in one.

Cost leadership, or more broadly defined, operational excellence, emphasizes efficiency and convenience. The aim is to attract customers by having the lowest price in the market while offering at least sufficient quality. Usually the products are not very differentiated, but come in one or just a few configurations. Mass production is a good way to create economies of ale, and there may a limited number of ways of interacting with customers. There should be no barriers for customers to order and use the product or service. Good examples of companies with this strategy would be EasyJet (or other low-cost carriers), ING Direct (offering standard products interacting through the Internet and call centers), and the Tata Nano car (offering a car for $2,500, which is about half the price of the cheapest alternative).

A differentiation or product innovation strategy focuses on having a unique offering, which allows the company to charge a premium. Keeping the lead in the market is a competitive differentiator; it requires the competition to follow, and keeps the barriers to entry into the market for others high. Organizations adopting this strategy invest heavily in research and development. As products and services are usually positioned in more exclusive market segments, the amount of units sold is usually lower compared to cost leaders, but the margin (and cost of sales) is much higher. Think of Apple (Macintosh computers and iPods), BMW (offering superior performance and cutting-edge new technology), and investment funds (seeking higher returns through creative and risky investment constructions). A variation on this theme would be brand mastery, creating loyalty because people care about the brand experience, such as with Nike or Coca-Cola.

Porter's definition of market segmentation is slightly different from Treacy and Wiersema's customer intimacy discipline. Market segmentation means focus on just a few market segments and know these markets inside out. Think of software vendors offering software for the telecom industry, or pharmaceutical companies focusing on various types of medication for cancer treatment. Products and services are tailored to the specific needs of that market. Customer intimacy is another type of focus, trying to understand the changing needs of different customer segments, and creating long-term relationships. Good examples would be all-round banks using database marketing to predict customer demand across a complete set of different products, retailers that differentiate product assortment per store and provide personalized diount coupons to customers, and airline loyalty programs that take personal preferences into account and provide special services for loyal customers. Whereas in product innovation people care about the brand, in customer intimacy and market segmentation, the brand cares about the people.

Traditional strategy says you cannot excel in each area. If your company focuses on operational excellence and cost leadership, you cannot afford the cost of sales and the R&D budget associated with a product innovation strategy or the extensive investments in customer relationship management that fit with customer intimacy. And a product innovation company usually has a culture that cares deeply about engineering and brand management, which is at odds with the cultural characteristics that fit customer intimacy.

However, others argue with that. Companies need to go beyond competing with existing competitors in existing markets, which is the basis of both Porter's generic strategies and Treacy and Wiersema's value disciplines. New profit and growth come from "blue oceans."[85] Blue oceans are new markets, where new demand is created. In existing markets, referred to as "red oceans," the structure of the industry, the business model, and market conditions are largely a given, or cannot be influenced directly. Markets may grow, but are basically a zero-sum game. Market share gained by one competitor is lost by another. In a blue ocean, competition is irrelevant as the first mover sets the rules of the market. In this view, innovation seldom comes from concrete market demand, but is always created on the supply side, based on inventions. Think of e-mail. No one ever asked for it—it was simply suddenly there.

Today, there are many blue ocean examples coming from co-innovation initiatives. Co-innovation happens when organizations, often in entirely different industries, collaborate to create new products or services, based on sharing complementary and unique resources and skills. For instance, Senseo is a one-touch-button machine for espresso coffee, based on the collaboration between Philips and Douwe Egberts. Philips created the appliance; Douwe Egberts a special blend of coffee. The Heineken Beertender is based on the same principle, where the beer comes from Heineken and the hometap from Krupp. Or think of the Nike+system, a collaboration between Nike and Apple, where a Bluetooth sensor that fits in your Nike running shoe sends running statistics to your iPod.

Although the idea of blue oceans is mostly connected to creating new markets or new types of demand, we can also apply the same principles to the creation of new business models. These would be applied in existing markets, but lead to an entirely different way of producing goods and selling them. Mass customization and customer self-service models have transformed many industries. Mass customization means products and services are produced based on the principles of mass production, aiming for low unit costs while at the same time offering flexibility of individual customization. Every single unit in the production process can have its own configuration. Or in terms of administrative systems, every transaction looks different. For instance, banks move from defining financial products to financial components that can be combined based on individual preferences and risk profiles. Pharmaceutical companies envision a future with personalized medication, where different active ingredients are combined based on the specifics of a patient's DNA. The number of options on a car nowadays is virtually unlimited. Mass customization is an example of breaking the idea of either/or strategy. You cannot start with mass customization without being operationally excellent; mass customization is a rather complex concept to implement. With operational excellence as the basis, the production process itself becomes the innovation. Keeping track of all customized orders also gives you deep insight into customer behavior, and you may even be able to predict customer preference—three birds with one stone.

Consider another example. Self-service models offer customers access to the organization's business systems, allowing customers to specify and alter their requirements themselves, and to monitor progress of their order. Think of airline booking systems, and online check-in. Often mass customization is combined with customer self-service. Dell builds computers based on specific customer requirements, entered through the web site. Insurance companies offer customers the opportunity to compose their own general insurance. Build-a-Bear is a retail chain that offers children the chance to put together their own Teddy-bear. There are web sites that connect consumers looking for a second-hand car to whatever car dealers have to offer. The twist on some of these sites is that the data about the age and origin of the car do not come from the dealer, but from the car registry office, which offers a much higher level of reliability than a traditional market web site. And, of course, web sites such as amazon.com not only offer a much more efficient and innovative ordering experience; they even recommend books, DVDs, or music that you might like based on "market-basket analysis" (customers who bought X also bought Y).

These blue ocean business models defy the idea of strategic choice. The innovation strategy focuses on the business model, which is part of the product experience. It leads to an entirely new form of operational excellence, where the customer takes over quite a bit of the work. At the same time, the organization is collecting a wealth of customer information through the web-based systems, enabling a longer-term relationship. Which strategic choice was made? The bar was raised significantly on all three levels—a strategic synthesis has taken place.

You could argue that this is simply extending the productivity border by using new technology, forcing a new optimum within the same strategic choices you have made, but I do not think this is the case. The way Porter described it, pushing the productivity border is an incremental and evolutionary process. The efficiency of existing processes is improved. Mass customization and customer self-service models are nothing less than a paradigm shift. Ironically, though, this synthesis becomes the new thesis and over time it becomes the new norm. Mass customization and customer self-service will lead to a reaction, the antithesis. And then a new jump forward is needed again.

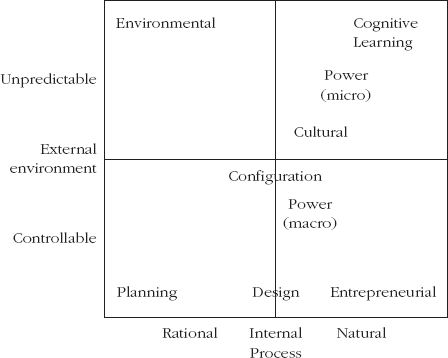

Strategy is a highly confusing discipline. First, there is no established definition of the term; second, there are no clear best practices on what process to follow. Figure 2.3 describes 10 schools of thought, each of which concerns itself with strategy and the strategy process.[86] Sometimes these schools of thought are complementary, but more often they flat-out contradict each other.

Figure 2.3. Ten Strategy schools of Thought Adapted from: Henry Mintzberg et al., Strategy Safari, Free Press, 1998.

These schools of thought can be classified using two dimensions. Some schools of thought focus on a very rational, structured process, others on a more natural, organic process. Some schools of thought see the organizational environment as controllable, to be analyzed and understood. Others see the external environment as highly unpredictable. The more stable a market is, the more classical strategy processes work. The more volatile the environment, the more another approach is needed. I think we all agree that most markets are volatile, and that the markets that seem stable compared to others are certainly less stable than they used to be. It is all the more astonishing that strategy processes are still viewed in such a traditional way, defining strategy in terms of planning, design, or power.

Common wisdom is that strategic management consists of three deliberate steps or phases: strategy formulation, strategy implementation, and strategy evaluation. In each, usually different people are involved, and each step has its own methodologies. According to today's best practices, strategy formulation consists of an internal and external analysis. For an external analysis, for instance, Porter's five forces model[87] is used, examining the competition in the market, the power of suppliers and customers, the threat posed by new entrants, and the threat of substitute products. The optimal corporate strategy is set to counterbalance those forces. The internal analysis looks at the resources available in and to the organization, the capabilities, strengths and weaknesses, and in more modern processes, the organizational culture. In the classical view this process is owned by top management, and is based on thorough analysis, and the success of the implementation is based on the rigor and the detail of the complete analysis. At the end of the analysis, all scenarios are evaluated and a choice for the single best strategy is made. This new-and-improved strategy is then handed over to middle management to be implemented, based on clear objectives.

Following strategy formulation, strategy needs to be implemented too. As in the classical view, "structure follows strategy," a reorganization may have to take place, putting in place the right hierarchy to deal with the various elements of the strategy. Through a top-down budgeting process, resources in terms of money and people are allocated. Several strategic projects are started to set up the right systems. The aim is to come to a focused and aligned organization. Focus means that the strategic goals are clear in everyone's mind. We know what to do and what not to do. Alignment traditionally means that we all share those strategic goals, and we all know our own specific contribution.

Strategy evaluation, then, is the feedback process, often also referred to as performance measurement or performance management. Performance indicators report to what extent the organization is reaching its goal. Based on where underperformance or overachievement is reported, additional analysis needs to take place to find out which corrective action needs to take place, or which lessons learned can be copied to improve performance elsewhere. It is a continuous process, traditionally called the PDCA cycle[88] (Plan-Do-Check-Adjust). Usually the focus of the process is on internal management control; it does not take external factors such as change in markets into account. We plan, execute, analyze the outcome, and see how we need to adjust our actions based on the outcomes so far.

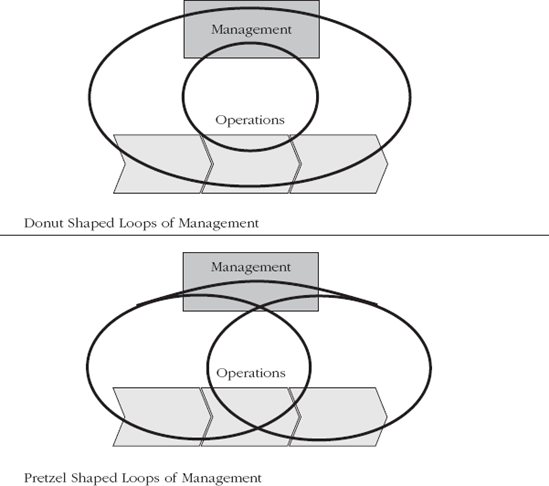

In a more visual way, we can look at strategic management as "loops of management," as shown in Figure 2.4.[89] The loops of management illustrate how strategy needs to be managed. The first, inner loop of management concentrates on monitoring the current state of things, in other words, strategy evaluation. Activities on the operational level are being monitored and the results are being measured against the targets. The moment the targets are not met or the measurements go in the direction of critical thresholds, adjustments need to be made. In the first loop of management, we generally let the decisions follow the facts; the decision-making process tends to be rather rational. We operate within the rules and confines of a predefined control environment and seek to protect that from discontinuities. Actions tend to be reactive and defensive. The second loop of management, or outer loop, represents strategy formulation. In the second loop of management, we seek improvement through change, not through control. The first loop of management focuses on measuring how the performance compares to the targets; the second loop of management focuses on whether we are still running the right processes, and whether we are measuring the right thing. Strategy implementation, then, is putting together a new set of loops in case of strategy changes.

Because of the explicit, disconnected nature of the phases of strategic management, the loops of management often look like a donut; the cycles go around independently. This creates a serious strategic dilemma that we can all recognize in the many organizations that work this way. Creating a new strategy is, in this line of thinking, considerable work. It requires reorganization, new systems, and new ways of working, so strategic changes will not happen very much. Only a few, big changes are possible; the organization does not have the agility to cope with more frequent, smaller changes. So, what if reality changes? That is a dilemma. If you choose to change before the natural due date of the strategy, it—again—will be an enormous amount of work. And if you do not change, well, you are out of touch—that is, if you even notice the changes in the outside world in time, as they tend to be picked up first in daily operations.

There is another school of thought that proposes a very different way of structuring strategy processes, called the learning school. This is where strategy is seen as much more of an evolutionary process. Proponents of this school believe that the environment of an organization is simply too complex to fully understand, and changes too often to control (and who can disagree with that?). Could Apple have known upfront that its iPod would be such a success that it would later decide to change the name of the company from Apple Computer to Apple? Would the German conglomerate Preussag AG, which decided to diversify after it became clear that coal mining did not have a future, have known that its travel business, TUI, would actually overtake Preussag and eliminate the original name of the company? Honda Motors definitely did not know that the 50cc motorcycles that early U.S.-based employees used to run errands would become the key to successfully entering the U.S. market. Honda's strategy was about positioning its heavier motor bikes, which on face value fit the American market much better. Cynics would be quick to add another definition of strategy: "the story you tell afterwards." In more neutral terms, serendipity—accidentally discovering something fortunate, especially while looking for something else entirely[90]—is often part of strategic success.

In short, uncertainty makes it impossible to come up with the single optimal strategy. The speed of change means you do not even have time to collect, interpret, and decide upon the information needed to come to such an optimum, should such information even exist.[91]

Deliberate strategies focus on control; the learning school of thought is more aimed at letting ideas emerge. The interaction between established daily routines and new situations is an important source of learning—the first moment a new phenomenon or a change in the market is experienced.

Moreover, allowing strategies to emerge taps into the creativity of the complete organization, instead of just the top management team. This does not mean that top management should sit back and wait for innovative things to happen. On the contrary; top management is there to guide the process and make sure that ideas that fit the theory of the business are tested based on conducting experiments. Strangely enough, this does not contradict the traditional strategists' appetite for structure and numbers at all. In fact, a "test-and-learn" approach to prove the value of an idea is one of the key characteristics of analytical firms.[92] Using a controlled environment and a test group can show the value of an idea before rolling it out on a global ale. With multiple experiments testing multiple variations of the idea, a good feel for the effectiveness of an idea can be tested before it is vetted as strategy. You could argue that the idea of "test-and-learn" is the strategic process in reverse. We start out by evaluating an idea, then implement and copy it on a wider ale, so that it becomes part of the corporate strategy. Moreover, the three phases of strategy—formulation, implementation, and evaluation—become a single process. It is a continuous cycle, where changes are picked up in daily operations, through a process of escalation evaluated on their strategic impact, and course corrections are immediately implemented. The loops of management form a pretzel, as shown in Figure 2.4.

There are two pathways to higher business performance.[93] In one, you can invent your way to success. Unfortunately, you cannot count on that. The second path is to exploit some change in your environment—in technology, consumer tastes, laws, resource prices, or competitive behavior—and ride that change with quickness and skill. This second path is how most successful companies make it.

Of course, you can criticize this way of thinking. In emerging strategies, ideas come from within existing structures. In other words, strategy follows structure, which is constraining. If structures need to change, this needs to come from the top. Another danger is what is called strategic drift. Slowly but surely, with each little increment, the organization drifts away from its intended direction. Emerging strategies may lack focus. Many wonderful small strategies do not make an effective overall strategy. There may be gaps, things that no one happened to think of. It may very well lead to a lack of alignment.

Clearly this is a dilemma in itself. Both a deliberate strategy process and strategy according to the learning school have dominant and unacceptable disadvantages. A synthesis is needed, combining the best of both worlds, fusing both approaches. The answer lies in organizing strategy according to the principles of strategic intent.[94]

Strategic intent starts with having a true understanding of the theory of the business, understanding the assumptions that form the foundation of the strategy. Every decision that is taken in the business, on the corporate level or in a certain business unit, needs to fit into that framework. If not, the decision should not be taken immediately, but further evaluated. Furthermore, there should be a very clear understanding of the goals—one clear picture that is easy to convey and instantly remembered, such as "Beat Competitor X," "Grow to 10 billion dollars," or "Do whatever is realistically needed to create a happy customer." Understanding the goal provides a clear sense of direction, and the strategic framework provides the guardrails to make sure the emerging strategies do not go astray. How? That is a question to which the answers unfold while we are on the road. There might be roadblocks, weather conditions may change, we may have to deal with fatigue while driving. All of these unforeseeable conditions will be dealt with once they arise, but we will never take our eyes off the goal.

Strategic intent also describes modern army doctrine. The field general describes the goal to his commanders in clear terms—there can be no misunderstanding about the focus. Which installations or other targets need to be destroyed? The alignment between the various army units is clear as well; each unit understands its own task and the tasks of others. Deadlines, handover points, and dependencies are perfectly clear, too. But how each unit moves through enemy territory, dealing with the landscape and unpredictable enemy movement, is up to each single unit. Translated to business, management is not defined as sticking to the plan, but as continuously looking for new ways to make it to the goal in a better, quicker, or more cost-efficient way. Structure and strategy go hand in hand; they are interdependent. Top management creates a structure fitting its strategic intent, and the organization comes up with new strategies within the boundaries of the structure. The structure is not limiting flexibility, but providing direction.

The biggest strategic dilemma occurs when strategy is out of sync with reality. It took too much time making a decision, leading to unfavorable circumstances, or the decisions were made too early, not taking critical circumstances into account. For example, we waited too long with creating an efficient business, and when times are tough we are forced to lay off large numbers of people. If we do not, we will suffer heavy losses, and if we do, we will suffer a severe brain drain in better times ahead. This dilemma is typically created by not making critical decisions in time, and sticking to the original plan too long. Conversely, if we bet the farm on a strategic direction a while ago and it cannot be reversed due to unforeseen market circumstances, we have an equally fundamental dilemma. If we change course, we may not survive as we do not have the resources and capability; if we do not change course, the ship sinks anyway as the tides have changed. Applying the principles of strategic intent prevents many instances of this dilemma from even appearing. We have eliminated the gap between changing circumstances and putting a change into place. And who knows? If we are skillful enough, we can drive a few changing circumstances ourselves. Remember, certainty is not found by avoiding uncertainty. Certainty is better defined as a process, coming to resolution of conflicting positions, applying Socratic reasoning as part of a continuous process of learning.

The third dimension of strategy, next to the content and the process, is the strategic context. No organization (or its strategies) stands alone. In the Porter point of view, the context is even the centerpiece of the strategy. Strategy is about positioning the company in the market, differentiating it from its competitors. This is in essence an interactive process. Every move from a competitor leads to a counteraction from other competitors; even sitting still can be a strong reaction. Although each change in strategy may be disruptive for the company plotting that new course, from a total market perspective it is incremental. Reaction follows reaction follows reaction. It is not all that dissimilar from the learning school of strategy. It is interesting that there is no such term as market drift, comparable to the strategic drift a company can display. The market is always right, and no one is in charge of the market, so how could it drift?[9] With one reaction leading to another reaction, and strategies being a response to competitive moves, the chances of strategic synthesis happening are pretty small. Thesis then only leads to antithesis, and antithesis will then lead to anti-antithesis—which is some kind of thesis again. Creating the synthesis requires seeing and understanding the thesis and antithesis, which is notoriously hard when you are part of the actual thesis or antithesis happening in the market. Synthesis comes from creating a new context, redefining the rules of the game—a blue ocean, if you will. Within existing markets, creating a truly new context happens only once in a while. And even less often does the change come from one of the established parties in the market, as they tend to have deeply entrenched and fortified positions.

Specific markets may each have their own dilemmas, within the context of that market. Take, for instance, the pharmaceutical market. Pharmaceutical companies need to be profitable, like any other company, if not for the good of the shareholders, then at least as a means to invest in the next round of the development of new medication. This sometimes requires high prices. At the same time, it is the task of pharmaceutical companies to improve the health of their customers, and from a wider point of view, of the general public at large. This would require prices as low as possible.

Or consider the oil industry, where business success has an opposite effect on the environment. During the 1990s, Shell needed to close down its Brent Spar oil storage installation off the coast of Norway. It did a thorough analysis and decided that the most economical, and technologically and environmentally safe solution would be to sink it. Unfortunately, pressure groups did not agree with this, and public opinion turned against Shell, leading to a customer boycott. It would have been better if Shell had sought a dialogue, which could have precluded these opposite positions.

Doing business in multiple countries provides a wide variety of cultural contexts as well, leading to interesting dilemmas. Should an American firm that acquires a French manufacturing plant abolish drinking wine during lunch in the cafeteria? Trying this might easily lead to a strike. Should a multinational bank allow a local branch to finance perfectly legal activities that are illegal or frowned upon in other countries? These dilemmas start with a discussion on corporate structure (how dependent or independent are legal entities), touch on competitive issues, and end with a moral debate.

Many strategic dilemmas can simply be prevented, as they are actually caused by "best practice" strategic thinking. "Strategy is about choices." "Strategy formulation is a discrete process that needs to be separated from implementation and evaluation." "Strategy is about competitive positioning." Understanding the theory of the business is the key to a different approach. What are your most important business assumptions? Do these assumptions still work or are they past their due date? Which likely events could invalidate your assumptions? What would be your strategic response?

As much as I have argued for creating options, there is nothing wrong with making choices. You cannot have a contingency plan for every possible future; not making any choices at all, while trying to go along with everything that passes by, leaves you unfocused and most probably unsuccessful.

The trick is to make the strategic choices that create the right options. That sounds like a paradox. If you make a strategic choice, you close the other options. However, it opens up the options that come with the choice you made. For instance, if you need to choose whether to open up a store in New York or in Boston first, only one can be the first. Assuming you choose Boston, this choice opens up all the options associated with being successful in Boston, like marketing to the local university, and making use of Boston-specific programs. You open up the choices of the "next level." The key to solving this paradox is to focus on the intention of the strategic choice. If the intention is to come to the single best strategy, this is the wrong intention. If the intention of the choice is to open up a maximum portfolio of options, this is the right intention. Strategy defined as creating options does not exclude strategic choice.

[9] Perhaps the 2009 recession, caused by the 2008 credit crunch, can be seen as a market drift. Collectively, all financial institutions invested in a bubble of subprime mortgages and other overly complex financial constructions, slowly moving astray from the real business.