In This Chapter

Identifying your investment style

Choosing between direct ownership or a nominee account

Before you can make the most of the financial information available to you, you have to establish a few simple points about the sort of person you are, and how much time and energy you're prepared to expend on the pursuit of financial nirvana. This chapter aims to help you achieve a perfect balance between making money and having a life.

I start this section by asking a few simple questions about your basic outlook on life, and on the investment world in particular. Your responses are important because they shape not just the way you use the information you get from the financial pages, but also the kind of information you go looking for in the first place.

Some people seem to be born with sunny dispositions, and some are the broody type. Some make friends easily and spend a lot of their time communicating busily with everyone around. Others are more private and self-sufficient, and achieve their best work when they're working alone on something too deep and complicated to be easily explained to other people.

That's fine. Life would be pretty tedious if everyone was the same. And, if you think about it, the financial markets would become pretty volatile if everyone was trying to achieve the same thing all the time. As soon as an opportunity opened up at the gates of Company A, people would all rush towards it at once so that it quickly became so crowded no point would exist in being there any more, and everyone would head to Company B or Company C, or wherever the action happened to be on that day. So thank goodness that whenever some of the investment herd starts driving up the prices of Company A, other people are taking advantage of the fact that Company B and Company C have suddenly got cheaper.

What you've got, then, is mutual synergy between the bulls and the bears, the old 'uns and the young 'uns, the steady hands and the over-excited. A kind of biodiversity keeps things on an even course. And that can't be bad, can it?

A bull is someone who reckons that stocks are likely to rise in the nearish future, and therefore that this looks like a good time to buy before prices go up. Bulls are, as they say, 'long' on equities.

That doesn't necessarily mean that bulls are optimistic about all shares. They might very well be talking about only one sector. You can be bullish on oil but bearish on banking stocks, for instance (or the other way round). You can be a FTSE bull (that is, you're planning to buy a tracker investment that shadows the performance of the FTSE-100 index, because you think the whole market will rise), or a dollar bull, or even a gold bull. But you're unlikely to be bullish on one particular stock – normally you're talking about a general mood that's lifted your spirits and made you want to splash your cash.

What sorts of things make people bullish? Mostly the usual macro-economic suspects:

Improving economic growth

Falling bank rates or lower inflation

Weakening energy prices

Strong employment statistics

Positive consumer/producer surveys

Fast-growing demand from some major export market

Certain positive factors don't normally elicit the term bull in the papers. For instance, if a takeover boom is going on within a stock market sector that's certainly excellent news for its investors, but calling it a bull market isn't quite right. Instead, the term tends to imply that something deep down in the economic bowels of the stock market is giving cause for optimism.

Equally, saying you're a bull just because you think some technical thing's about to happen isn't appropriate. For instance, if you expect a big share-purchasing spree at the end of the year as the City types scramble for their Christmas bonuses, that hardly makes you a bull, just a sharp observer with an eye for market timing. A bear, on the other hand, thinks that things are soon going to the dogs. Like bulls, bears are viewing the macro factors. And again, bears aren't usually talking about just one investment. Rather, they're looking at the whole blackening sky and reckoning that the thunderstorm is due to start any time soon, for example:

Declining economic growth

Rising bank rates or higher inflation

Energy prices going up

Disappointing employment figures

Gloomy high-street surveys

A sinking currency that may make foreigners avoid UK investments

A bear's first instinct is to sell whatever she thinks is about to go steeply downhill as a result of the impending storm. That may even include selling her house. (Yes, some property bears spend years living in rented accommodation in the hope of being able to buy back into the property market at a cheaper price.) But on the whole, one of the major differences between bulls and bears is that bulls go out looking for investment opportunities while bears are inclined towards damage limitation. After all, once you've sold your shares you can't do much else, can you? Well, bears can consider shorting, as described in the nearby sidebar.

People tend to stick to their own approaches to they invest their money. And for good reason. No two investors are every the same. People are in different life-situations: some of them are young and able to take risks, while others are nearing retirement and need to keep their risks under control. Some people are investing 'fun money' that they won't miss if they lose it, while others know that their lives will change for the worse if they get it wrong. Some people get a buzz out of picking their shares, while for others it's just a bore and a worry. In which case they'll be better off backing a range of investments and letting somebody else do all the work, even if it means having to pay them a commission. We're all different, and that's the way it ought to be.

You don't have to sign up for anything when you become a contrarian investor, a day trader, or a long-term buy-and-hold devotee (see the following sections), and you don't have to learn any Masonic handshakes or funny walks to be accepted in any of these circles. But reading a few books is a good idea before you start laying down your money, because each of these groups has its own little vocabulary of specialist language, its own preferred techniques, and its own ways of reacting to any bits of news – good or bad. Spoiling a solid, tried-and-tested investment approach because you jumped to the left when the rest of the gang were jumping to the right is a shame.

Read the following examples and see whether you recognise your own approach in any of the outrageously extreme stereotypical investing behaviours.

Income investing makes some people yawn. The press use the term to describe buying an investment mainly for the sake of the dividends or the interest cheques, rather than for the capital gains that you make if you've bought and sold your shares wisely. Most cash investments, such as bank or building society deposits, are income products. But the same can apply to any kind of share that happens to pay high dividends to its shareholders. Or, of course, to the tax-free National Savings investments (bonds, equity funds and cash accounts) that brighten so many retired people's lives.

In Chapter 5 I talk about the sort of people who favour income investments. They tend to be long-term investors who don't like surprises and who try to avoid risks whenever possible. Often their tax situation means that they're better off with income than with capital gains. Thus, for example, a person setting up a trust to save for a child's school and university fees probably opts for income investments: partly because they can effectively use up her income tax allowances, and partly because their low level of risk makes them attractive.

A third type of people go looking for income, and they're the people who use tax-effective instruments such as Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) or self-invested pension policies (SIPPs) to 'roll up' surprisingly large sums of money over several decades.

Note

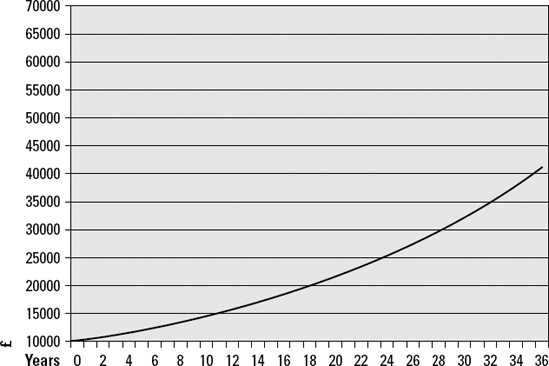

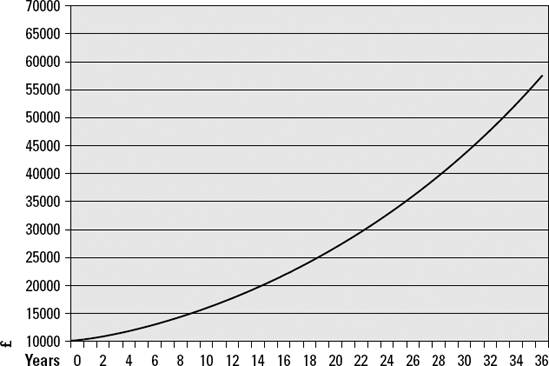

According to Albert Einstein, the most powerful force in the universe is compound interest. If you invest a £10,000 lump sum in a share that gives you a reliable 4 per cent dividend (after tax) just once every year, come rain or shine, and if you carefully reinvest it every year, you quadruple your money in 36 years even if the share price doesn't budge at all – see Figure 4-1. But if that yield goes up by just a measly 1 per cent to reach 5 per cent a year, you very nearly sextuple it – see Figure 4-2.

The growth rate's even faster if the dividend payments are half the size but come in twice a year instead of just once. Impressed? Aye, perhaps those old pipe-smoking bores are wiser than they look.

The issue, of course, is that you do have to be really very sure that your income investments really are as reliable as they seem. In Chapters 2 and 3 I show you a few supposedly safe and predictable bets that turned out to be anything but. So take care, and don't get misled by mere numbers.

You also need to spend a little time deciding whether an Individual Savings Account (ISA) or some other form of investment may give you the best protection from HM Revenue and Customs. At one time an ISA was the ideal way to get your dividends tax free; but now that the special dividend tax breaks through ISAs have more or less vanished, a self-invested pension policy (SIPP) or even a trust of some sort may be a more tax-effective way of going about the task. But that's getting outside the scope of this book, which is about the financial pages. For more details on these thorny issues, read the excellent guides to Investing for Dummies and Investing in Shares for Dummies.

Long-term buy-and-hold (LTBH) strategies are still the most popular techniques among investors. Basically, you buy a share that you think's going to be a good 'un for the long term, and you don't worry too much about whether it happens to be up or down by 5 per cent or so on this particular week because you've got your eye fixed firmly on the far horizon.

An averagely active investor probably spends a lot of her time worrying about nothing. If the price of Acme Screws goes down 5p when the market opens in the morning, she's going to watch the price all day to see whether or not some bad news is unloaded on the market, or if Washington is about to launch an embargo on European screw imports, or whatever. And nine times out of ten, she hasn't done anything about it by the time the market closes at the end of the day. No buying, no selling, just watching. Active investors spend a lot of time watching. And drinking coffee, and chewing their fingernails.

In contrast, LTBH investors spend a lot of time sitting in their armchairs, or getting on with their work, or playing with their families and thinking about what they're going to have for supper. LTBH investors have more fun!

They also have the pretty considerable advantage of being able to sleep much better at night, because they don't clog up their brains with stressful stuff. Staying fixed on the long-term horizon is an excellent way to stay sane.

Back in the good old days before the Big Bang revolutionised the London market in 1986 (see Chapter 3), LTBH was the only kind of investing that really made sense for an ordinary citizen. High broking commissions and heavy taxes meant that making a share purchase cost you around £30 in mid-1980s money – probably closer to £70 in today's money. So you weren't exactly going to be nipping in and out of the market every few days in search of a hairline profit. Instead, you relied on your financial adviser (usually your broker) to set you up with a portfolio that didn't need too much trimming and adjusting. You probably feel the same way about your pension plans right now: you just want to set something up and let it run for years on end with very little attention from you.

That said, of course, you do have a choice. The Web is full of cheap broking deals that let you trade as often as you like, and at the instantaneous push of a button, for as little as £6 per trade. And since you only pay stamp duty on purchases, not on sales, you may find just going ahead and trading very tempting.

Value investing is for people who are in a hurry to get places and don't intend to wait around. If you hold that the market is inefficient and prices are often 'wrong' in relation to the underlying value of the companies involved, all you really have to do is buy the shares while they're cheap and sit tight until their real value's revealed. And then you cash in. Dividend yields mean next to nothing, except that they can be a useful flag to show that something's out of kilter in the share valuation; and, according to some value investors, even debts don't count for much – you're after capital growth, and a share price ignores both of those things when things are going well.

But you can't be a value investor without taking bigger than average risks, and you have to be a bit of a whiz with the calculator (not to say an expert in company accounts) to work out which shares the market's outrageously ignoring and which ones are just putting on a brave face to disguise the fact that they're genuinely rotten to the core. If the idea of taking on this task doesn't frighten you, then you may qualify to join the gallant band of value investors.

Where value investors really differ from most people is that they don't mind digging around among the fallen ruins of once-mighty companies for their trophies. And nor are they afraid to tread in those two warrens of booby-traps that pass by the innocent names of the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) and the over-the-counter (OTC) market.

AIM shares are more lightly regulated than normal listed shares, meaning first that the financial reporting requirements are relaxed for these companies, and secondly that most of the normal protective restrictions on how much of a company one person can own go right out of the window, so you can sometimes find yourself well and truly snookered by a management that plays fast and loose with its own power. Buyer beware, unless you have deep pockets and an unerring instinct for a bargain.

A value investor's response is normally to say: 'Yes, AIM companies are also ineligible to go into a tax-efficient ISA or a PEP, a fact that may be of some concern to you if you consider that probably half of all AIM-listed companies go bust. And rather more in the case of OTC shares.

I understand all that. Now please stand aside and let me invest my money. I'll buy 20 companies, and if 10 of them go completely under at a 100 per cent loss I'll still have made a good profit because the other 10 will have cleaned up.'

The remarkable thing is that they're generally right in the long term. Over the two and a half decades since the first lightly regulated companies were allowed into their own corner of the stock market, AIM-type investments have soundly beaten the overall long-term stock market averages.

Overall. Long-term. Note those words carefully. One of the biggest problems that value investors have to face is that value opportunities tend to come and go in cycles. During some periods, maybe years on end, AIM companies absolutely bomb – mostly when interest rates are high (because troubled companies tend to be in a lot of debt), or because the market is just wobbly and all the mainstream investors have pulled back their money into lower-risk investments.

Where do you look for enlightenment if value investing's your chosen path? To the company accounts, of course, and also to Internet-based forums like ADVFN (www.advfn.com) and the Motley Fool (www.fool.co.uk). You spend a lot of time scouring blogs for clues, but you're suitably careful because an awful lot of rampers exist. (Rampers are people who buy cheap but rotten shares, then tell everybody how good they are and sell as soon as the price goes up, leaving their victims to choke in the dust.)

Tip

Apply a share-filtering system. They're available for free on the Internet from the likes of ADVFN, iii (www.iii.com.uk), and Hargreaves Lansdown (www.h-l.co.uk/shares). At the press of a button you can apply a filter to the whole stock market that lets you find the highest yields, the lowest price/earnings ratios, the best debt ratios, and all sorts of other useful stuff that helps you find candidates for the bargain share of the year.

Back in the mid-1990s, when the Internet was just starting to make home share trading seem like a viable option for the average punter, day trading briefly became the dinner party subject. I must have met dozens of clever young people with big black circles under their eyes who told me they were making fortunes by buying and selling shares at the push of a button, maybe a dozen times a day, in the comfort of their own home. The trick, they said, was to find a share that you thought was looking a little bit peaky on a particular day, and then buy it in the hope of offloading it later the same day at a modest profit. If you did this often enough, they said, all you had to do was make enough to pay your rock-bottom dealing costs (£6–10 per trade, typically) and you'd be laughing. Every night you 'closed down all your positions' (that is, sold all your holdings) and went to bed on your profits or your losses. Keeping your positions open for two days or more was strictly for wimps.

Ten years on, I doubt whether many of these people are still using the comfort of their own homes in the same way. Their partners have left them, their children hardly recognise the square-eyed creatures they've become, and in some cases their homes are no longer their own. You struggle very hard to find anybody who's making money in any consistent way through day trading.

And yet the lure of the quick day-trading buck endures. Intelligent people are still gambling with both their money and their sanity in a practice that's only half a step higher than going down to the local betting shop, and twice as addictive.

Day trading's twice as addictive as gambling because, unlike a horse race, you really feel completely sure – instead of only fairly sure – that your skills can help you turn a small profit. You're not being greedy either – just a 3 per cent profit on the day suits you fine. And when things go wrong you always have a convenient reason to hand.

Tip

If you can't resist the allure of day trading (against my best advice), you need a specialised online account that lets you see every deal, everywhere in the country, listed in real time. (But it'll cost you extra. Normal mortals only get access to so-called 'Level 1' share prices, which are usually released only after a 15–20 minute delay.) You also need a battery of statistical tools, including those for charting (see Chapter 10), to help you make your snap decisions.

I think I've made my point. But if you really, really insist on this ridiculous practice, you can day trade more effectively by using one of the many spread-betting services that companies like CMC (www.cmcmarkets.co.uk) or Paddypower (www.paddypower.com) can offer you. With these services you're backing whole stock market indices, rather than single companies, and your profits are tax free.

Of course you want up-to-the-moment charts, and the ones you can get for nothing from LiveCharts (www.livecharts.co.uk) are better than most.

Warning

Be under no illusion, though, that day trading has anything to do with proper investing. You take no interest in actual companies or their fundamentals – you only second-guess which way the market is likely to move in the next six or eight hours. That's not much better than tossing a coin, except that you're paying commissions for each toss. The dealer always wins.

Despite some superficial similarities, know-it-all tactics such as conventional value investing and day trading are about as far as you can get from the stunning investment habits that have made Warren Buffett the world's richest man. With a net personal worth of $62 billion, the 'Sage of Omaha' shot past Bill Gates in Forbes magazine's March 2008 survey, having earned another $10 billion during a year when the American stock market had fallen by 4 per cent. Yes, the S&P 500 index had got 4 per cent poorer and Buffett had got 19 per cent richer – in the same year.

Many things make Mr Buffett such a successful investor, and if I knew even a tenth of them I'd be writing this book on the deck of my very own yacht. Nobody else seems to know, that's for sure. I can start by saying that Buffett's essentially a value investor with that essential extra streak of genius that lifts him well above the crowd. But then, I can also say that Buffett does a prodigious amount of research work that hardly anybody else is bothered to do. That he can dissect a company's accounts with more precision than almost anyone. And that his intelligence, his rigorous approach, and his cheerful resilience have stood him in good stead. But ultimately, Buffett's success is down to one very simple strategy. He believes that the market is wrong so much of the time that you can actually build a successful investment strategy out of always doing the exact opposite of what everybody else is doing.

Well, not exactly always. That's a popular misconception. Quite a lot of the time the markets have the situation sized up pretty well and although opportunities exist, they really aren't big enough to be worth exploiting. But every so often – maybe only once or twice a year – the chance is available to make a big profit out of the market's error. And so you spend your life looking out for these so-called contrarian opportunities. When you're not doing that, you sit on your wallet and resist the urge to buy anything at all.

According to Buffett:

'Investors should remember that excitement and expenses are their enemies. And if they insist on trying to time their participation in equities, they should try to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful.'

Like I say, contrarianism takes discipline, and more than most people ever possess. Indeed, Buffett takes discipline to an extreme that few think worthwhile. Whereas you or I buy a cheap share, let it ride upwards, and then hope to sell it at its peak, Buffett says that once he's bought a share he tries his very hardest never to sell it. That's because he likes the big dividends that large 'mature' mainstream industries can afford to pay. Buffett's a secret long-term buy-and-hold fan as well.

So, assuming that you don't have Buffett's towering intellect or his humungous wallet, can you gain anything useful from the financial media to help you spot the occasions when the Emperor's tailors have sold him a see-through suit?

Indeed you can. You can, and should, do your very best to read as much as possible of the great man's thinking on life, money, and the follies of the financial world. They call Buffett the Sage of Omaha because his annual shareholder addresses at his company Berkshire Hathaway's shareholder meetings attract hundreds of thousands of people who enjoy his unfussy, down-to-earth, and often witty style.

Read Buffett's best gems online atwww.berkshirehathaway.com under Shareholders' Letters. Or make a start by looking him up on Wikipedia (www.wikipedia.com), which may keep you supplied with enough anecdotes to keep you laughing while you learn about the secrets of the contrarian/value approach he's made his own.

That's not much of a starting point for a beginner to follow, is it? Better, perhaps, to try to establish a mindset that simply isn't afraid to ask even the stupidest-sounding questions. Because every so often they turn out to be the sensible questions that nobody else thought to ask. That's what they taught me at the Financial Times, and the advice hasn't failed me yet.

I may not shock you too much by saying that most successful investors don't restrict themselves to just one of these approaches. I've got a sprinkling of LTBH investments in my portfolio, together with a couple of industrial stocks that were just too much of a bargain to miss when I saw them going cheap a couple of years ago. I have some utility shares that bring in fat dividends come rain or shine, which is a great comfort to me when the investment skies are darkening. And I've dabbled in small company shares, although without much success, I must admit.

I've been known to buy shares on the contrarian principle that a stock that everybody hates must have something going for it. That was how I bought the transport operator Stagecoach's shares back in 2002 for 27p and sold them a year later for 70p when the market had come to its senses. The one thing I've never tried my hand at is day trading. But then, I do need my beauty sleep.

The two most common ways in which you can own shares – or bonds, or unit trusts, or practically anything else, really – are in your own name, or through an expert who holds them in a so-called nominee account, which means that although the expert's the holder, the law recognises you as the beneficial owner.

I also make a passing reference to the use of trusts in which to hold your investments. I don't go into much detail here, because trusts are more of a taxation issue than an investment issue – and besides, they're quite fiendishly complicated, and are subject to tough laws that change all the time.

For most people, owning your investments directly and having them in the drawer is simply the most logical thing to do. You're spending your money, after all, so why shouldn't you have all the paperwork and all the ownership documents made out in your personal name?

The advantage, obviously, is that you know exactly where everything is, and that you don't need to worry about the honesty and good behaviour of people far away whom you've never met. Also, if you should pop your clogs unexpectedly, your inheritors can find all the necessary bits of paper right there in your desk drawer – or, more probably, in your bank's vault – rather than having to go online and track down your holdings the hard way via some faceless office in the Channel Islands where you're known as a username and a password.

More importantly, perhaps, you know that your name and address appear on the company's shareholder register, instead of the name and address of the Channel Islands office. This means that you, and not somebody else, get the invitations to attend the annual shareholders' meeting and munch the company's Jaffa cakes with your fellow investors. If the company decides to do anything controversial, such as accepting a takeover offer, you're invited to have your personal say in the matter, instead of the Channel Islands person you've nominated to exercise your rights for you.

You also get the benefit of any shareholder perks: the little favours, discounts, and sometimes quite big handouts that some companies make available to their shareholders (see Chapter 3 for more on these).

The downside, however, is that you may need to do a little more of the tax paperwork yourself if you're the one with all the documents. And a slightly bigger chance exists of you getting nuisance calls from people who've looked you up on the register in the hope of selling you other investments.

Sorting out your own investments nearly always costs you more than doing them through a nominee account. You're hard pressed to find a private stockbroker's dealing costs that can compete with the £6–8 that now passes for normal among the cut-price, 'execution-only' brokers on the Web. ('Execution-only' brokers don't offer you any advice about what to do - instead, they simply obey your instructions.)

Of course, you don't get the personal service and advice – or indeed, any advice at all! – from the nominee accounts these people provide. Nor are they quite so flexible as a private broker if you decide to leave a limit order. (That's a standing instruction that the broker buys or sells something if a particular price ever moves above – or below – a specified level.)

So you face a trade-off between cost and flexibility, inconvenience and possible nuisance, with the added disadvantage that a nominee account doesn't normally get you your shareholder perks. (Of course, you may decide that you rather like the anonymity of not being on the shareholders' register.)

One time you're definitely going to find a nominee arrangement an advantage is if you decide to buy gold certificates or some other kind of proxy gold. Gold certificates like the Perth Mint Gold Certificates run by the government of Western Australia allow you to hold the legal equivalent of a bar of gold without ever needing to have the physical object shipped to your house – where it makes a useless doorstop that just keeps you awake at night and pushes your insurance bills up.

Then again, you're already using the services of half a dozen nominees, whether you know it or not. Your pension funds, your endowment mortgage, and your five-year stock market-linked bond from the building society are just three examples of nominee arrangements. Your child trust funds are very probably being administered by a nominee account set up by the fund arranger. And if your life assurance policy is designed so as to build up a nest-egg alongside the normal cover it gives you against death, that's another one.

The all-important question is, are any risks involved in letting a stranger get between you and your financial holdings in this way? What happens if your intermediary turns out to be a crook who disappears off to Bolivia with your cash? What if an unforeseen emergency forces her company into bankruptcy?

Relax, you're fine as long as the nominee company is registered with the Financial Services Authority, which includes any company that's legally allowed to solicit your business on the UK mainland. Any nominee accounts with these companies are rigidly policed and controlled, and the FSA 100 per cent protects and guarantees your money in the event of any cataclysm. Even if a financial disaster wrecks the bank that's handling your private banking account (that's another nominee arrangement for you), you're okay because your holdings are in another pot entirely. The bank's shareholders might whine, but you don't need to because your money is safe.

Trusts are a complex and fast-changing environment in which to hold your shares, and one that's neither fish nor fowl as far as the law's concerned. I'm not going to discuss them too deeply here, partly because trusts are so complicated, but partly also because you can't set one up without engaging a solicitor, who's much better placed to advise you than I am.

Some unscrupulous people use complex 'blind' trusts to try to make sure that HM Revenue and Customs can't find out who the beneficial owners of an asset happen to be. (But watch out, because the Revenue's bloodhounds are getting better at their job these days.) Others use trusts in a less obviously underhand way to ensure that their children's tax allowances are used to the best effect in an offshore location.

Still others use trusts to manage foreign property portfolios or to reduce their inheritance tax liability– activities that may involve moving large quantities of cash, bonds, or other securities to some location that's temporarily beyond the Revenue's reach (this is perfectly legal as long as you declare the eventual profits).

Special trust rules apply to people who aren't British nationals. Certain Islamic investment instruments must be handled through a trust in order to comply with Shari'a law. And so on. You get the idea.

What all these devices, both legal and otherwise, have in common is that an apparent stranger – who may indeed be a genuine stranger, but often isn't – becomes the agent the authorities have to deal with, instead of the beneficial owner herself. The general effect is that a kind of legal fog is allowed to develop between the beneficial owner, who's theoretically powerless to control the actual assets, and the Inland Revenue, which generally prefers to treat her as the owner and administrator.

Trusts work well for some investors and not for others, so if you think you may benefit from one seek out professional advice from a solicitor.