In This Chapter

Handing things over to an expert

Locating information on trusts and funds

Differentiating between unit trusts and investment trusts

No matter how good your own stock-picking skills may be, there are probably going to be some times and some situations where you'll probably want to leave the choices to somebody else. Leaving another person in charge of your savings means that you're free to get on with your life and do the things you want to with your time, instead of spending every waking moment wondering whether the Nikkei is heading down the tubes or the FTSE's being overvalued.

Anyway, of course, you already do employ professional fund managers to run your investments on your behalf. Your pension funds are a prime example of letting somebody else do the legwork – and let's remember that, even if your employer runs your pension scheme, it's a professional manager who's actually investing your cash. As for those guaranteed income bonds you bought last year – to say nothing of your endowment mortgage – none of them would function at all without somebody at the controls to get on with the daily grind of selecting and monitoring the things that will go into your portfolio.

But I'm assuming, for the moment, that you rather enjoy the thrill of the chase, and that your investing record so far hasn't been so terrible as to make you think that you really ought to give up and do something different. What, you ask, is so wrong with your own stock-picking that you should feel the need to bring in a hired hand?

Nothing at all, probably. I thoroughly enjoy picking the stocks that have brought me a modestly successful result over the years. But there are some areas where I know that I'm in right over my head, and where I really do prefer to let somebody else take control of the tiller.

If you're investing in a country whose local language you don't speak, employ someone who does. If your Japanese isn't up to much, you don't gain much from trying to invest in the small companies that are making so much of the running in Tokyo these days, because so few of them disseminate any of their shareholder information in English. Then again, if you don't know how a Chinese company likes to treat its investors and its business partners, you may be in for a few shocks when little things like business protocol start to get in the way of what you may think are cut-and-dried deals.

If you're investing in the Middle East, you need somebody who understands the ways of Islam. If you want to run a few Russian investments, a manager who knows her way round the silent hierarchy of powerful people who control so much in the Russian business world is a real help.

Another situation where a good pilot can make all the difference is when the technical aspects of the industry in question go right over your head. Only an analyst with the right blend of investment skills and an in-depth knowledge of the sector can get you the right results when the little details count. Is the plusfix matrix count system really going to revolutionise the home security system, or will the regenerative synastic loop knock it out of contention? (All right, I confess, I made up both of these innovations, but you get the idea.) Naturally, you can try to beat the experts by reading everything you can find about the companies and technologies you're interested in – that's one task the Internet's very useful for – but at the end of the day you're likely to find yourself reading the fund managers' commentaries in the newspapers and simply doing what they recommend anyway.

But perhaps the greatest joy of using a professional pilot instead of operating alone is that your manager can spread your money over a much wider range of stocks than you'll ever manage to do yourself. If you have £5,000 to invest and you buy ten different lots of shares in ten different companies, you'll probably end up spending £200 (4 per cent) on handling charges and stamp duty, plus another £10 in commissions when the time comes to sell any one of them. Your manager will probably scoop up all the charges for a flat initial fee of less than 1 per cent and a management fee of maybe 1 per cent a year, possibly even less.

In aviation circles, the joke goes that if you look inside the cockpit of a modern passenger aircraft you'll find a pilot, a computer, and a big fierce dog. The computer's job is to fly the plane. The dog's job is to bite the pilot if he/she tries to touch the controls.

Most of the tracker funds you meet in the course of your everyday investing are a bit like that. With only rare exceptions, no humans are in charge of the investment process – instead, the computer takes all the decisions, and the human just does what he or she's told. Buy this, sell that, press this button to authorise the transaction, and I'll do the rest..

That's good news for everybody, of course. First, the pilot (sorry, I mean fund manager) doesn't make personal mistakes that reveal his human vulnerability to those good old emotions, greed and fear.

And secondly, an automated process means that the fund's much less likely to miss out on a trend because somebody just hasn't noticed it.

But for most other fund situations the pilot's still very much at the controls, and his knowledge makes an awfully big difference.

The problem with looking up the latest information about managed funds is that there's so much of it, and none of it seems to go very deep. One glance at the back pages of the Financial Times, which lists seven full pages of listings in microscopic print every single day of the week, is enough to get you whimpering for the long-lost simplicity of your post office account.

I mean, who reads all that stuff? The experts. And are you an expert? Of course not. Surely you can find a better way of sifting through all that crashingly boring detail and selecting the best buys.

You can. Nearly every fund that this chapter considers has a unique identifying code that you can type into your computer and get all the useful information your heart desires. Plus graphs, sectoral weighting breakdowns that tell you which funds are investing in which companies, and much more besides.

Each fund is known by a three- or four-letter code called a TIDM (which used to be known as an EPIC), or an ISIN (if it's an investment trust or a foreign fund), or a SEDOL, which is the same as the ISIN, but without the GB800 code that tells you it's British. Often a fund has all three of these codes at once. For instance, the Blue Planet European Financials investment trust is known by the following:

TIDM: BLP

SEDOL: 0532707

ISIN: GB0005327076

With the code information in your hot little hand, you can now call up masses of information by typing any of those identifiers into Google, or FT.com, or (my own favourite) Trustnet (www.trustnet.com). You're able to set up charts that compare how the fund's fared against the FTSE-100, or against the sector average for other funds of its own type, or simply against the market average for funds of that particular type.

Trustnet gives you an almost unlimited range of options for selecting your top performers. You can have them ranked in order of the funds that are doing best, or the fund providers that are getting the best results, or the geographical regions that are producing the best profits for the funds that invest in them, or the industry sectors that are performing best.

And in case all that's not enough, you can choose which time span you want your performance leagues to cover. Do you want to know the top performers over the last year? Or the last three years? Or the last five? And do you want your information sorted according to how the funds' own values performed, or are you more interested in the growth in their underlying assets, the so-called net asset values? (See 'Understanding discounts and premiums', later in this chapter, for more on these.)

Monthly investment magazines also provide listings showing which funds have been turning in the best performances over the last couple of years. You can dump your money into these funds before walking away whistling. Job done. These magazines also provide details of how to contact the various sales offices once you've made your decision. Investors Chronicle, Money, Shares, and What Investment? are just four of the names that spring to mind.

If you put your money away for the long term you need to keep an eye on your fund manager. Often, a fund achieves a glittering performance under one particularly talented manager, only to plummet when she leaves the fund provider in search of a better future with another company.

Does your fund provider tell you when its star manager jumps ship? Not likely. If it thinks you're going to sell off all your funds and move your money to the manager's new company, it does everything in its power not to let you know.

Tip

The serious financial papers often tell you when somebody changes jobs, but if you want a really comprehensive run-down of job moves you can find one at Trustnet (www.trustnet.com), which has a section called Fund Manager News in its News Archive section. Keep an eye on it.

The basic idea behind a unit trust is incredibly simple. You give your money to a fund provider, and she puts it into a big bag with other people's money and uses it to buy a portfolio of shares. You buy so-called units, each of which represents your fair share of all the value in the portfolio, and the fund provider publishes an update on the value of the portfolio every few days, quite often every single day.

Until the 1930s no pooled investments existed – and even up to the 1960s they were pretty thin on the ground. Instead, you either bought dozens of shares in order to give you a safely diversified coverage of the sector you were interested in – a very expensive process in those days – or else you bought one or two and crossed your fingers.

It's probably fair to say that unit trusts are going slightly out of fashion these days. Investors don't like being charged all the fees that unit trusts almost invariably entail – and they certainly don't like the idea of being forced to sell their units back to the original vendor when they're ready to move on. That's because selling unit trusts back to the vendor creates a situation where he can suck her teeth like a used car dealer and offer the seller a much lower price than he's going to charge the next punter who wants to buy them. (The gap between the buying and selling price is known as the bid–offer spread, or occasionally the bid–ask spread).

Besides, now that we've all got Internet trading and Trustnet, and investment trusts and Exchange-Traded Funds (ETFs), amateur investors have much better access to the tools they need in order to make their own decisions. Some day, unit trusts are going to disappear completely.

Or are they? You probably don't see the full advantages of unit trusts until you see the big downside in the investment trust idea. They may be more expensive than investment trusts, but they're a lot more stable over the long term. And surely, peace of mind is one of the things that you're trying to achieve?

The unit trust manager never quite knows how much of her investors' money is going to be in the bag at any one time, so she can increase or decrease the number of units in circulation to suit the mood of the moment. In effect, the fund can shrink or grow in response to the need. Unit trusts are an 'open-ended' investment vehicle (in contrast to investment trusts, which can't expand or contract and are therefore 'closed-ended').

Warning

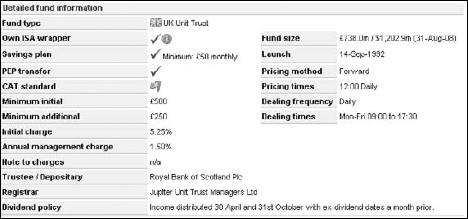

The fees involved in unit trusts can be steep. The example in Table 14-1 has a 5.25 per cent initial charge, which is going to knock quite a big hole in your capital, and thereafter you're charged 1.5 per cent a year just for managing it. That's because the unit trust really is being managed by a real live human being, not a computer, and she needs to be paid.

You can often reduce these initial fees by buying your unit trusts through a fund supermarket rather than getting them directly from the fund provider. Sometimes you can get the fees right down to zero.

But you may also come up against a hidden catch when the time comes to sell. The provider sells you the fund at the 'offer' price, which is likely to be rather higher than the 'bid' price at which she's prepared to buy it back from you if you're selling rather than buying.

Table 14-1 shows how one website lists the daily bid and offer prices for a popular unit trust, the Jupiter Merlin Growth Portfolio. As you can see, the bid's more than 5 per cent less than the offer, which is a nice way of saying that the provider's creaming off another 5 per cent of your money at the end of your relationship. That's 5 per cent that you don't have to pay with an investment trust!

Table 14.1. Prices for a typical unit trust

Bid (GBX) | 186.42 |

Offer (GBX) | 196.47 |

Change (Bid) | + 0.41 |

Per cent change** | + 0.22 |

Tip

The unit trust manager probably only buys additional shares for her portfolio once a day, so you can forget any ideas you may have about being able to catch the market in mid-afternoon, the way you can if you're buying the shares directly. In effect, the prices are set once a day, and the unit price you're likely to pay is whatever price prevails at the close of play.

You don't have any trouble getting daily prices for unit trusts. The FT does a good job of providing daily prices, as well as the net asset value information that underpins the daily unit valuation (turn to 'Understanding discounts and premiums', later in this chapter, for more on net asset values).

But for a deeper analysis, Figure 14-1 shows Trustnet's evaluation of the same unit trust as in Table 14-1. As you can see, the unit trust comes with its own optional 'ISA wrapper', meaning that you can buy it in a tax-efficient form if you want to. You have to buy a minimum £500 worth, or commit to at least £50 a month if you're buying it through a savings builder plan.

The fund's been going since September 1992, and the last time it released any information about its size, in August 2008, it was worth £738 million.

This particular unit trust issues a dividend twice a year, which is payable in April and October. Many unit trusts don't provide dividends, however.

Trusts come in all shapes and sizes to suit all sorts of needs. If you want to get some easy exposure to the oil industry, you'll have no difficulty finding a trust to suit your tastes. Or if you fancy buying into the East European property markets, suitable candidates are bound to exist.

The great joy of unit trusts is that the presence of an experienced manager gives you an important safety net when you're venturing into unknown areas. And the relative price stability of the funds helps you sleep at night.

]UCITs and OIECs may sound like some fearsome kind of monsters from a Tolkein story, but in practice they're a lot more friendly and rather less likely to turn round and bite you without warning. Especially if you give them the capitalisation they deserve. They are a relatively recent invention set up at the instigation of the European Union in an effort to make trusts more freely available across the national borders of the European financial area.

OEICs ('open-ended investment companies') are a first cousin to unit trusts, in that they're open-ended funds where the provider can create as many units as it likes, or cancel them when demand shrinks. As such, the unit price always reflects the value of the underlying investment assets, rather than shooting up and down with the fluctuating rate of investor demand.

But one very important difference with an OEIC is that it's a limited company or plc in its own right, just like an investment trust (see 'Investment Trusts', later in this chapter), rather than merely being a division of a big fund provider. That's bound to seem rather strange, given that the OEIC can shrink or grow at will.

Another very attractive difference with an OEIC is that it doesn't have 'dual pricing' like a unit trust. Instead of having a wide difference between the bid price and the offer price, as shown in Table 14-1 and Figure 14-1, an OEIC has just one central price for both buyers and sellers. What you see is what you get.

So you don't need to go looking for bid and offer prices with an OEIC, because there aren't any. What you do need to watch, though, is the steeper level of fees. Initial charges are frequently higher than for unit trusts, and so are the annual management charges.

The very name UCITS (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) has that unmistakeable dead hand of European bureaucracy about it. But UCITS mean well, honestly. The general idea is that any provider of either an existing unit trust or an investment trust can apply to Brussels for an approval note that will allow it to promote its products anywhere in the EU: the main point is that the approval gives you certain guarantees about the minimum standards of protection and the quality of the financial reporting. But Brussels also hopes that this initiative will enable the providers to reduce their hefty charges because they're able to address a much larger target audience than before.

These days, about 70 per cent of all European trusts have been successfully registered as UCITS. In time, all of them are presumably going to follow suit.

Investment trusts (ITs) are everything that unit trusts are not (see the previous sections). They're not 'open-ended' funds that can shrink or grow at will to accommodate the level of demand for their services. Instead, every IT is a limited company, with a once-and-for-all initial budget that's all gone when it's all been invested in a suitable portfolio of investments.

After that initial buying phase – which may take months or even years to complete! – the trust's only way of growing any further is to increase the value of its underlying assets through successful stock-picking, and to get itself noticed by investors like you and me so that everyone wants to come and have a piece of its success.

Investment trusts can invest in any kind of portfolio they like, as long as it's within the limits of their statutes. For instance, a property IT isn't allowed to invest in food retailing companies, but it might be allowed to own pieces of the companies that buy the superstores and then lease them out to Sainsbury's and Morrisons. All ITs are allowed to hold cash, of course, because money's always rattling around when something's being bought and sold. But that's about as far as their leeway goes.

And that's where the vexed question of discounts and premiums starts to come into the picture. As you saw with unit trusts, eEach trust has a net asset value (NAV) – which, in simple terms, represents the market value of all the investments in its portfolio.

Note

Let's set up a rather simplistic example to illustrates this. If an IT owns 10 per cent of a company whose market capitalisation (that is, its current stock market value) is £500 million, and another 20per cent of a company that's worth £1 billion, then you'd say that its total net asset value iwas £250 million:

| (£500 million × 10)/100 + (£1,000 million × 20)/100 |

| = £250 million |

Supposing the fund has issued 100 million shares, its NAV is 250p per share. But if it's having a good year and the stock market's taken a particular shine to it, its actual share price may rise as high as 275p. The trust is then trading at a 10 per cent premium to its NAV.

Actually, this situation isn't very common. Normally when the stock market looks at an IT, it tries to calculate in all the costs that it incurs if it decides to get rid of all its holdings tomorrow. For instance, it probably has to sell its holdings at less than they're really worth, and it has dealing charges, experts' fees, and probably taxes to pay. So the market normally wants to knock off a fairly big chunk of the NAV when it tries to value the trust. All things being equal, the market's probably inclined to award the trust a value of (say) 237.5p, which is a 5 per cent discount to the NAV.

Many investors refuse point blank to buy an IT at a premium. The premium's a sure sign of irrational exuberance, they say, and the purchase is bound to end in tears.

You don't hear very much about investment trusts in Britain. For reasons best known to themselves, the regulatory authorities regard ITs as too risky for the average investor to tangle with. Accordingly, advertisements for ITs are restricted to the trade press, and you almost never find them mentioned in the Sunday papers.

What's the problem? Officially, it's because ITs tend to be more volatile than some other types of investments. In practice, however, ITs incur much smaller fees and other charges than unit trusts, so fewer incentives exist for the trade to promote them.

Bearing this lack of information in mind, here are some facts about investment trusts:

ITs are simply shares like any other. Each trust is a limited company or plc in its own right, and it has a unique EPIC or TIDM code that you can use at any time to track its performance (flip to 'TIDMs, SEDOLs, and ISINs', earlier in this chapter).

Most of the ITs you come across in Britain are listed on the London Stock Exchange (LSE), just like any other share. You don't find them in most daily newspapers, but the online services at the FT or the LSE give you instant coverage.

You can buy ITs in other countries besides Britain, but the paperwork can be a hassle. Try using Exchange-Traded Funds as an alternative (Chapter X has more on these).

You can buy ITs through your Individual Savings Account, just like any other share – except for a few that list themselves on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) and are banned from ISAs for that reason. This means, in effect, that you can buy as much as £7,200 worth a year.

ITs are liquid, effective, and often very keenly priced.

With a unit trust, the price of your investment is firmly fixed in relation to the net asset value ('Understanding discounts and premiums', earlier in this chapter, explains how to work out the NAV). With an investment trust, the price is determined by the underlying level of demand for the trust's shares, which is continually rising and falling. Unlike a unit trust, the IT can't just cancel some of its units if demand starts to drop off. Instead, its size is fixed, and so it has to weather the storm if demand drops away suddenly.

The premium or discount enters the picture at this point. If an IT's been successful for many years, a lot of people may have been happy to pay a premium to net asset value for its shares. But as soon as the price starts to fall, the investor's going to sit up and say:

| 'Oh no, I've been paying a 10 per cent premium to net asset value for those shares, and now the NAV has dropped by 5 per cent. That means I'm 15 per cent out of pocket! Better move fast before the situation gets any worse.' |

That's nothing. Investor 2's going to say:

| 'Help, Investor 1's bound to sell her holdings now that she's 15 per cent over-exposed. I'm not quite that badly off, but I better get moving as well before she can phone her broker.' |

Meanwhile Investor 3's been doing her sums. The falling NAV that frightened Investor 1 is starting to look decidedly shaky now that Investor 1 and Investor 2 have both decided to pull out. The racing certainty's that the NAV's going to fall even further once their sell trades hit the City's screens. 'Nothing for it but to beat them both to it' she says. 'I get my retaliation in first.'

The result? You have the makings of a mini-panic, which will drive prices down rather further than they really ought to go before eventually somebody sees reason and starts buying the ITs up again.

Note

Investment trusts are always more volatile than the underlying securities they hold. And much more volatile than unit trusts, which aren't subject to the same exaggerated laws of supply and demand. None of this would happen if ITs could grow or shrink on demand, like unit trusts. In this respect, their similarity to shares is their great weakness. Except that, with shares, nobody ever pays a premium to the market price!

Do you see now why so many IT investors won't touch a premium?