Chapter 23

The Management of Positions

23.1 INTRODUCTION

Once trades have been executed, they create positions. If the quantity purchased of a particular instrument exceeds the quantity sold, then the position is a long position; if the quantity sold exceeds the quantity purchased, then it is a short position.

During the life of a position, there are a number of events that take place. Some of these events are externally driven and result from actions taken by the issuer of a security, or by the nature of a derivatives contract or the legal agreement underpinning a debt instrument, while others are internally driven and arise from good financial practice. Table 23.1 summarises all the events that are examined in this chapter.

Table 23.1 Position events

| Event description | Event driver | Instrument types affected |

| Interest rate fixing | Legal documentation of contract or debt issue | Swaps, floating rate notes |

| Interest (coupon) payment | Legal documentation of contract or debt issue | Swaps, all types of debt instruments, money market loans and deposits |

| Collection of maturity proceeds | Legal documentation of contract or debt issue | Swaps, all types of debt instruments, money market loans and deposits |

| Dividend payment | Equity issuer | Equities |

| Corporate actions | Equity issuer | Equities |

| Contract expiry | Exchange that developed the contract | Futures and options |

| Funding of positions | Internal process/good accounting practice | All instruments |

| Mark to market | Internal process/good accounting practice | All instruments |

| Reconciliation | Internal process/good accounting practice | All instruments |

| Interest accrual | Internal process/good accounting practice | All instruments except equities |

Before we examine each of these events in detail, we shall first of all cover the difference between trade dated, value dated and settlement dated positions.

23.2 TRADE DATED, VALUE DATED, SETTLED AND DEPOT POSITIONS

The trade dated position is the net quantity of an instrument or contract bought or sold up to and including the most recent trade, while the value dated position is the net quantity bought or sold where value date is equal to or earlier than today. The settlement dated position is the net quantity that has settled on or before today. If trades always settle on the correct value date, then the value dated position and the settlement dated position would be one and the same. The depot position is the actual amount of an instrument that a settlement agent holds on behalf of its customer, and the depot position is the sum of the settlement date position + stock borrowed – stock lent.

It is essential to understand the difference between these concepts because some of the events need to be applied to the trade dated position, some to the value dated position, some to the settlement dated position and some to the depot position.

Many firms employ the use of a stock record, usually part of the main settlement system, that enables them to view positions on a trade dated and value dated basis. The stock record was examined in Chapter 15.

23.3 INTEREST PAYMENTS AND INTEREST RATE FIXINGS

Most forms of debt instruments, as well as OTC derivatives such as swaps, pay periodic interest payments or coupons at regular intervals. The only exceptions to this rule are zero coupon bonds which were issued at a deep discount to face value, bonds that were issued by companies that are no longer able to fund the interest payments (in other words bonds where the issuer is in default) and swaps where the counterparty is in default. For floating rate notes and the floating side of swaps, the interest rate for the next coupon period also needs to be “fixed” a few days before the end of the current interest period.

23.3.1 Interest rate fixings

Example

National Grid plc EUR 750 million floating rate instruments due 2012.

This bond pays quarterly coupons of EURIBOR + 35 basis points (one basis point is 1/100 of 1%) on 18 January, 18 April, 18 July and 18 October) each year.

18 January 2008 is a Friday, a normal working day for the euro. Shortly after 11am on Wednesday 16 January (fixing date)-two working days before the start of the next coupon period – the value of three-month EURIBOR will be published on pages 248 and 249 of Reuters. This is the rate that will apply to the next coupon period. In the case of the National Grid bond, the interest rate that applies will be the published EURIBOR rate plus 35 basis points. Firms that trade instruments based on benchmark rates such as EURIBOR and LIBOR will need to access these Reuters pages, update the static data about the bond issue concerned in the relevant systems and use this rate for any transactions that settle during the next coupon period. The same applies to bonds that are fixed on other benchmark rates such as LIBOR or US Federal funds – these rates will also be published by Reuters, Bloomberg and other information providers.

For swap cash flows, the process is identical. Two working days before the start of the next coupon period the firm needs to access the relevant page, update the contract data in the relevant systems and use this rate to determine the coupon payment to be paid or received at the end of the next coupon period.

Note that fixing dates are usually two working days before the start of the next coupon period. Business applications that are concerned with interest rate fixings include diary functions that predict the fixing dates for the life of the bond or the derivative contract. These applications need to use working day calendars and holiday calendars to predict these dates. Refer to section 10.8 for more information.

23.3.2 Interest payments on bonds

Determining entitlements

On the coupon date – the first day of the next coupon period – holders of bonds will be paid the regular coupon payments that they are owed by the issuer. Holders are owed the amount based on their value dated positions on record date, which is usually one day before coupon date. However, these payments are made to them by their settlement agent acting in its role as custodian of their assets, and the settlement agent will pay the coupon amount based on their depot position. This means that the coupon amount paid may differ from the amount owed by the net value of any overdue unsettled deals, and also by the net borrowing/lending position.

Where a firm’s depot position is not the same as its value dated position, it will need to claim any coupons due to it, and pay any coupons due to others, from the trading parties concerned. Sometimes this process is automated for the firms by their settlement agents who automatically adjust the settlement amount of trades that settle late by the value of any coupons that have been paid to the wrong party, but on other occasions there may be the need to make a claim from or proactively organise payment to the trading parties concerned.

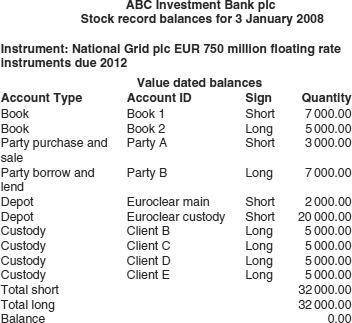

Firms that use a stock record as part of their settlement system will use the stock record to identify the internal trading books, external trading, lending and borrowing parties and depots that need to be debited or credited with coupon proceeds. Consider Figure 23.1, which is an example of a value date stock record report.

Figure 23.1 Stock record used to identify beneficiaries

In this example, Euroclear will pay this firm the coupon on face value of 2000 for the settled position in its main depot account and face value 20 000 for the depot position in its custody account. The 20 000 received for the custody depot needs to be distributed to the four custody clients – B, C, D and E.

Book 1 needs to be debited with the coupon on its short position of 7000 and Book 2 needs to be credited with the coupon on its long position of 5000. Party A has failed to settle a sale to ABC before record date, so ABC needs to claim the coupon on face value 3000 from that trading party. Finally, ABC needs to pay a coupon on face value 7000 to Party B, from whom it has borrowed the bonds.

Coupon calculations for FRNs

There are a small number of differences between the way that coupons are calculated and paid for straight bonds and for floating rate notes:

1. The affect of non-working days on payment date: For FRNs, if a predicted coupon date falls on a non-working day, the date is adjusted according to rules laid out in the legal documentation of the bond concerned. The most common rules are as follows, but any bond issuer is free to mandate an alternative rule:

- Roll forward until end of month: Assume a coupon date of the 25th of the month. The first time that this falls on a non-working day (say a Saturday), the coupon rolls forward to Monday the 27th. The next coupon will also fall on the 27th, and the same test is made for the next coupon date, which may cause it to roll forward again. However, once the roll-forward process has reached the last calendar day of the month, it stays there – it never rolls forward into the following month.

- Roll backward until start of month: The same principle as roll forward, but the first time that the coupon falls on a non-working day it is rolled backward to the previous working day, and the next coupon date will also be based on this day. However, once the roll-backward process has reached the first calendar day of the month, it stays there – it never rolls back into the previous month.

- Roll forward, express dates: Assume a coupon date of the 25th of the month. The first time that this falls on a non-working day (say a Saturday), the coupon rolls forward to Monday the 27th. The next coupon date, however, will revert to the 25th of the month because this date has been expressly written into the legal documentation.

For straight bonds the date remains unchanged, even though the holder will receive the coupon one day later. Adjusting the coupon date on an FRN affects the number of days in the interest period.

Fixing dates are also amended using the same rules as coupon dates.

2. The amount of coupon to be paid where the coupon period is less than one year: For FRNs the amount of coupon to be paid in a particular interest period depends upon the number of days in the period. Refer to section 3.2 for the common methods of determining how many days there are in an interest period.

For straight bonds that pay semi-annual or quarterly coupons, the amount paid on each coupon date is not affected by the length of the coupon period; a bond bearing a 4% coupon and paying semi-annual interest will simply pay 2% at each coupon date.

23.3.3 Interest payments on swaps

Interest payments on swaps work in the same way as interest payments on bonds, the fixed side of the swap behaves like a fixed rate bond and the floating side behaves like an FRN, with the following exceptions:

1. Swap interest payments for each side are netted, the party that has the most to pay makes a net payment to the other party – refer to the swap examples in section 5.5.3.

2. There is no party acting in the role of custodian, so it is up to each party to ensure that payments are made and received on a timely basis.

3. When swap floating side coupon dates and/or fixing dates fall on non-working days, they are adjusted in the same way as they are adjusted for FRNs.

23.3.4 Accounting for interest payments

In order to ensure that the amount received for a particular coupon payment is the same as the amount due, most settlement systems incorporate coupon control accounts. Consider the following example.

Bond A pays a 4% coupon. On record date, two trading books of ABC Investment Bank each have a value dated position of 50 000. The depot position is only 80 000. The difference is caused by a single overdue (purchase) settlement of 20 000.

On coupon date, the settlement system automatically credits the interest income account and debits the coupon control account with two lots of 2000 (50000 * 4%). The settlement agent will actually pay the firm 3200 (80 000 * 4%) which will be credited to the coupon control account. The balance of this account will therefore be 800.00 debit, which is the amount owed to it by the trading party that has failed to deliver 20 000 face value of the bond concerned. When the firm manages to collect the 800.00 that it is owed, it will credit it to the coupon control account, which will then have a zero balance.

In accounting terms, the entries that pass across the general ledger for this type of account may be represented as shown in Figure 23.2.

Figure 23.2 Coupon control account entries

23.4 COLLECTION OF MATURITY PROCEEDS

Bonds and swaps mature at the end of the borrowing period. For an interest rate swap, there is no maturity event as such as no principal amounts are exchanged, but for a currency swap it is up to both parties to return the principal amount to each other. Refer to the example transactions in section 5.3.

For bonds, the firm’s settlement agent will arrange for the securities to be withdrawn from the firm’s depot account on maturity date and the cash to be credited to its nostro account. The amount withdrawn should be the same as the form’s value dated position according to the stock record.

Most settlement systems incorporate the use of a redemption control account to control the collection of maturity proceeds. The redemption control account works in the same way as the coupon control account illustrated in Figure 23.2. On maturity date, the settlement system automatically debits the position account with the maturity proceeds and debits the same amount to the redemption control account. When the settlement agent pays the maturity proceeds, the amount paid is credited to redemption control, which now has a zero balance. If, one day after maturity date, there is still a non-zero balance on the redemption control account, then the matter requires investigation.

23.5 DIVIDEND PAYMENTS

Dividend payments are the distribution of earnings to shareholders, and are the result of a decision made by the directors of the issuing company. Dividends are usually paid in cash denominated in the issue currency, but may sometimes be paid in other currencies or sometimes paid in the form of stock. Depending upon the country of issue, dividends may be paid once, twice or four times each year. The directors may, of course, choose not to pay a dividend.

Dividends are paid on dividend date to holders based on their value dated positions as of record date, which may be several weeks before dividend date. Ex-dividend date varies according to the rules of the market in which the securities are listed, but in many markets it is usually two working days before record date. After the stock exchange closes on the day before the ex-dividend date and before the market opens on the ex-dividend date, the price of all open good-until-cancelled, limit, stop and stop limit orders are automatically reduced by the amount of the dividend, except for orders that the customer indicated “Do Not Reduce”. This is because these trades cannot settle until after record date, and the new owners will not receive the dividend concerned.

Dividends are paid by the firms’ settlement agents based on the depot position, so the same problems that were described for bond coupons also apply to equity dividends when the value dated position and the depot position on record date are not identical. The stock record may be used to work out the entitlements to dividends in the same way that it was used to work out coupon entitlements in the example described under “Determining entitlements”, page 219.

Unlike bond coupons, neither the dates nor the amounts of dividend payments are predictable until the dividend is announced by the issuer. Firms use a large number of information services such as those provided by Reuters, Thomson, Bloomberg, the various stock exchanges and also their settlement agents to advise them which issuer is paying a dividend (and how much they are paying) on which dates.

This information is usually uploaded into each firm’s settlement system or static data repository, so that automatic postings may be made to a dividend control account that serves exactly the same purpose as the coupon control account described in section 23.1.5.

23.6 CORPORATE ACTIONS

Corporate actions are events initiated by a public company that affect the securities issued by the company. Coupons and dividends may be considered examples of corporate actions.

Equities may be subject to corporate actions. The primary reasons for companies to use corporate actions are:

1. To return profits to shareholders: Cash dividends are the classic example.

2. To influence the share price: If the price of a stock is too high or too low, the liquidity of the stock suffers. Stocks priced too high will not be affordable to all investors and stocks priced too low may be delisted. Corporate actions such as stock splits or reverse stock splits increase or decrease the number of outstanding shares to decrease or increase the stock price, respectively. Buybacks are another example of influencing the stock price where a corporation buys back shares from the market in an attempt to reduce the number of outstanding shares thereby increasing the price.

3. Corporate restructuring: Corporations restructure in order to increase their profitability. Mergers are an example of a corporate action where two companies that are competitive or complementary come together to increase profitability. Spinoffs are an example of a corporate action where a company breaks itself up in order to focus on its core competencies.

Corporate actions may be classified into two types – mandatory and voluntary.

A mandatory corporate action is an event initiated by the corporation by the board of directors that affects all shareholders. Participation of shareholders is mandatory for these corporate actions. The shareholder does not need to do anything to get the benefits of the corporate action – it is just a passive beneficiary.

A voluntary corporate action is one where the shareholders either elect to participate in the action, or have a choice as to how they will receive the benefits provided. A response is required by the issuer to process the action. The shareholder may or may not participate in the tender offer; if it wishes to it sends its instructions to the corporation’s registrars, and the issuer will send the proceeds of the action to the shareholders who elect to participate. Sometimes a voluntary corporate action may give the option of how to get the proceeds of the action. For example, in case of a cash/stock dividend option, the shareholder can elect to take the proceeds of the dividend either as cash or additional shares of the corporation.

23.6.1 Corporate action examples

Table 23.2 shows examples of the most common forms of corporate actions.

Table 23.2 Common forms of corporate actions

| Name | Description | Investor action required? |

| Bonus issue | Additional shares are given to existing shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholding free of cost. | None – mandatory |

| This has no effect on the valuation of the holding. If a holder owned 100 shares with a market price of £6 each and received a bonus issue of 50 shares, then the share price would fall to £4 per share | ||

| Share split or stock split | The total number of shares in issue is increased, and the additional shares are given to existing shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholding free of cost. Like a bonus issue, a share split has no affect on the valuation of the holding | None – mandatory |

| Reverse share split | The total number of shares in issue is reduced, and shares are taken from existing shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholding free of cost. Like a bonus issue, a reverse share split has no affect on the valuation of the holding | None – mandatory |

| Merger or takeover | Company A offers to acquire Company B. It may pay shareholders in cash, or in securities issued by Company A, or by a combination of both | Voluntary – shareholders have to elect whether they want to sell or not, and if they do whether they want cash or stock. |

| Spinoff | Company A divests itself of one or more activities by forming Company B, and giving shares in Company B to Company A’s shareholders in proportion to their existing shareholding free of cost | None – mandatory |

| Rights issues | The company offers existing shareholders the rights to acquire new shares in the company at a discounted price | Voluntary – if the shareholder does not take up its rights they may be sold on the stock exchange concerned |

| Share buy-backs | The company offers to buy back shares of existing holders and cancel them | Voluntary |

| Exercise of warrants or options | The investor decides to acquire new shares in a company by exercising warrants or options over those shares | Voluntary |

| Conversion of convertible bonds | The investor decides to acquire new shares in a company by exercising its right to convert some or all of its holding in a convertible bond | Voluntary |

23.6.2 Corporate action processing

Introduction

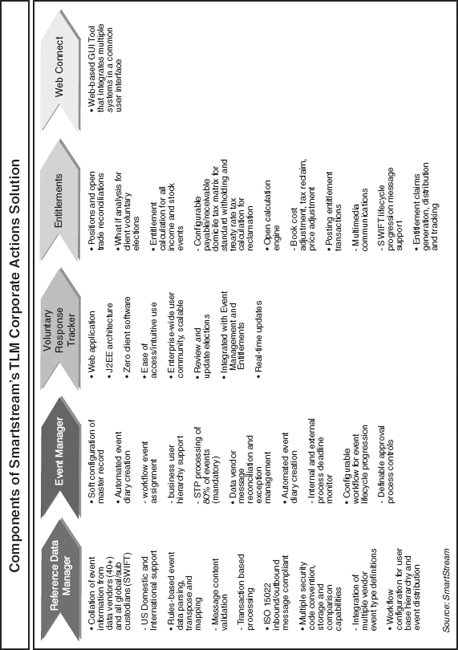

Corporate actions processing has traditionally been a function of core settlement systems, but in recent years a number of software vendors have produced dedicated packaged applications designed to manage and control this activity. The firms that have adopted them are often those that have a large number of client (usually safe-custody) positions to manage. This means that communicating the nature of voluntary actions to each client, establishing which option each client wishes to take, and then consolidating the results to the settlement agent represents a significant cost that may be reduced by automation. The dedicated corporate actions packages are usually based on workflow applications, which deliver exceptions to the desks of individuals who can manage them. The use of workflow technologies is very helpful in tracking correspondence between the firm, its customers and its settlement agents, and dealing with situations where customers are not giving their instructions for voluntary corporate actions in the correct timeframe.

Figure 23.3 is an illustration of the functionality of one such system, Smartstream TLM Corporate Actions™.

Figure 23.3 Components of a corporate actions package system

These standalone corporate action systems also support the messaging standards used by the major providers of corporate action information. The relevant SWIFT standards are shown under Table 23.3.

Table 23.3 SWIFT messages relevant to corporate actions

Processing stages

The steps involved in corporate action processing are similar to those of dividend processing, except where voluntary actions are concerned. Corporate actions have an announcement date (the date on which the company announces its intentions) as well as a record date and payment date. When corporate actions are voluntary there is an additional step involved in finding out the wishes of the holders of the security concerned. Depending on the business profile of the firm processing the action, “the holders” might include any or all of the following:

- The firm’s own trading books

- Clients for whom it is holding securities in safe custody

- Clients for whom it is providing investment advice

- Trading parties from whom it has borrowed stock, and therefore has a responsibility to provide the right outcome for them.

The stock record may be used to work out the entitlements to corporate actions in the same way that it was used to work out coupon entitlements in the example in Section 23.3.2. When the firm has ascertained the holders’ intentions, it then has to communicate them to the firm’s settlement agent, who will process the action in the firm’s depot account. Once again, each holder’s entitlement to corporate action proceeds will be based on its value dated position, so if there is any discrepancy between the value dated position and the depot position, there will be a discrepancy in the amount paid or received. A corporate actions suspense account (which behaves like the coupon and dividend suspense accounts) is used to control this discrepancy. The settlement agent will notify a “closing date” – the latest date that it can accept its customers’ instructions – and often a default action – the choice that it will elect if it doesn’t receive any instructions in time.

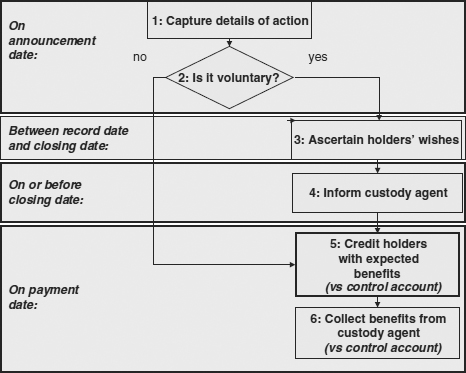

The steps involved in processing corporate actions are illustrated in Figure 23.4.

Figure 23.4 Corporate action workflow

Step 1 (announcement date) Capture details of the action: The firm will receive details of the corporate action from its settlement agent very shortly after it is announced by the issuer. In addition, a large number of information vendors supply corporate actions information in electronic form.

Step 2 (announcement date) Decide whether it is voluntary: This step involves reading the message content. If it is voluntary, and the firm processing it has a large number of clients affected, then it needs to go to Step 3, else it goes to Step 5.

Step 3 (between record date and closing date) Ascertain the holders’ wishes: This step may be broken down into the following:

- Step 3a Identify the holders: Firms that use a stock record (see Chapter 15) will identify the holders from this part of the settlements application.

- Step 3b Decide how to communicate with the holders: If this firm’s holders are retail investors, it might decide to send them a letter or an email, paraphrasing the information that it has received. If, in turn, these clients are advisory clients (refer to section 7.4), then it may go further and make a recommendation to them. If on the other hand the firm’s clients are institutional investors, then it may simply forward the messages that it has received in substantially the same form. However, the message carrier may change on a case-by-case basis; for example, this firm may have received notification by a SWIFT message, but not all of its investors are SWIFT members.

This message needs to include a closing date – the latest date that it is possible for the firm to execute the holders’ instructions. This may need to be earlier than the closing date that was advised to this firm by its own settlement agent in order for the firm to be able to complete Step 4 in time.

- Step 3c Send the message to the holders and await responses

- Step 3d Follow up any missing or ambiguous responses: The modern corporate actions packages usually provide workflow-based facilities to support this stage.

Step 4 (on or before closing date) Inform the settlement agent of the actions that it needs to take: This step usually involves responding to the electronic message that the settlement agent sent in Step 1 with an appropriately formatted electronic message.

Step 5 (payment date) Process the corporate actions: This step involves crediting the holders’ accounts with the benefits that are due to them and ensuring that the settlement agent credits our firm. The other side of these accounting entries is the corporate actions suspense account.

Relevant SWIFT messages for corporate actions

The relevant messages are as shown in Table 23.3.

Because of the textual complexity involved in describing corporate actions, the MT568 is used to provide any supplementary information that cannot be contained within the structural constraints of the other messages.

Business applications used to process coupon, dividend and corporate action activity

Traditionally, coupons, maturities, dividends and corporate actions processing capabilities have been provided by the firm’s main settlement system. In the past 10 years several software vendors have produced dedicated corporate action processing applications to provide these facilities. Most of these new dedicated applications are based on workflow technology.

23.7 LISTED DERIVATIVES – CONTRACT EXPIRY AND DELIVERY DATES

23.7.1 Listed options

Listed options have an expiry date. If the option is not exercised before this date, then it expires and has no value. The exchange that developed the contract will provide details of the expiry dates of each option, and the relevant clearing house that services the exchange will provide message formats that are used to exercise the option if required. If the holder wishes the option to lapse, then it need take no action.

23.7.2 Listed futures

Expiry date is the time when the final price of the future is determined. For many equity index and interest rate futures contracts (as well as for most equity options), this happens on the third Friday of certain trading months. After the expiry date of a futures contract the key date is known as delivery date or final settlement date. Because a futures contract gives the holder the obligation to deliver or receive the underlying instrument, when delivery date is reached the holder of a long position must deliver, and the holder of a short position must receive. In practice, delivery occurs only on a minority of contracts. Most are cancelled out by purchasing a covering position – that is, buying a contract to cancel out an earlier sale (covering a short), or selling a contract to liquidate an earlier purchase (covering a long).

Settlement is the act of consummating the contract, and can be done in one of two ways, as specified by the exchange concerned for each futures contract that it lists:

- Physical delivery: The amount specified on the underlying asset of the contract is delivered by the seller of the contract to the exchange, and by the exchange to the buyers of the contract. Physical delivery is common with commodities and bonds.

- Cash settlement: A cash payment is made based on the underlying reference rate, such as a short-term interest rate index such as EURIBOR, or the closing value of a stock market index.

The exchange that developed the contract will provide details of the expiry dates, settlement prices and delivery dates of each futures contract, and the relevant clearing house that services the exchange will provide message formats that are used to make cash or physical settlement as required.

23.8 MARKING POSITIONS TO MARKET

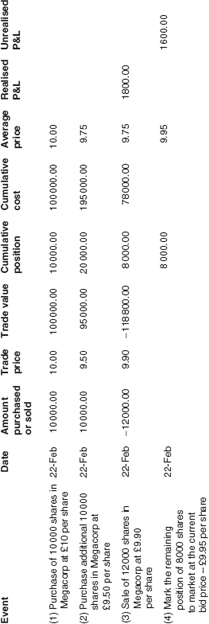

Mark to market is an accounting procedure by which assets are “marked”, or recorded, at their current market value, which may be higher or lower than their purchase price or book value. As a result of a mark-to-market calculation, all investments are valued in the dealing system at their current market value, and all profits and losses that result from price rises or falls are recognised on the day that they happen. This is accounting “best practice”. Consider the following example.

On 22 February, ABC Investment Bank carries out three trades in Megacorp plc:

1. It buys 10 000 shares at £10 each at 9am.

2. It buys an additional 10 000 shares at £9.50 each at 10am. At this point its position is 20 000 shares and its average price per share is £9.75.

3. It sells 12 000 shares at £9.95 per share at 11am. Its position is now 8000 shares, and it has made a realised profit of £1800.00. This is calculated as:

![]()

At the close of business the bid price of Megacorp on the exchange is 9.95 per share and the offer price is £10.00 per share. Because ABC has a long position in Megacorp, it marks the trade dated position to market at the bid price. If the position were short, it would mark it to the offer price. As a result, it calculates an unrealised profit of £1600.00. This is calculated as:

![]()

In addition, as a result of the mark-to-market calculation, it is now holding the position in its book at a new price – £9.95 per share, the current bid price.

If it were to sell some or all of its holding in Megacorp on 23 February, then it would calculate the realised P&L for that day as:

![]()

In other words, the close of business mark-to-market price on day 1 becomes the opening average price on day 2. The profits and losses (both realised and unrealised) are posted to the firm’s general ledger on the day that they occur.

In this example, the revaluation (or marking to market) of the portfolio was based on the weighted average price (WAP) method of revaluation, which is usually expressed by the following formulae:

For a long position:

![]()

And the cost of an amount sold (which reduces the long position) is expressed as:

![]()

For a short position:

![]()

And the cost of an amount purchased (which reduces the short position) is expressed as:

![]()

When a transaction takes the position from long to short, or from short to long, then the weighted average price of the resulting position is the same as the price of the trade.

The transactions in this example are summarised in Figure 23.5.

Figure 23.5 Mark-to-market example

23.8.1 Mark to market: practical issues

Which transactions and positions are normally marked to market?

Positions in bonds, equities and listed derivatives are normally marked to market in the manner described in this section, using closing bid and offer prices for the instrument concerned. FX positions also need to be marked to market in the same way, this time using the closing exchange rates of the currencies concerned to the firm’s FX base currency. Swaps are marked to market using the procedure described in “Marking swap transactions to market”, page 232

Determining accurate bid and offer prices

The closing bid and offer prices of liquid equities are published each day by the stock exchanges on which the shares are quoted. For illiquid equities that are traded over the counter, and for many corporate bonds, finding an accurate independently verifiable source of bid and offer prices is more difficult. MiFID (see “Post-trade transparency”, Section 8.4.2) introduced requirements for market makers to publish pre-trade quotes and also mandated post-trade publication of all executed OTC trades, and a number of exchanges and central matching engines collect such data and publish the results in summary form. The information that they publish may be used to ascertain realistic bid and offer prices for many instruments.

As far as illiquid corporate bonds are concerned, many investment firms will base their decision as to what the accurate closing price of an individual security is by referencing the individual bond to a liquid government security denominated in the same currency. For example, if the yield on a 30-year US Treasury bond is currently 4.5%, then the yield on all AAA rated straight corporate bonds with a similar maturity might be 60 basis points higher, while the yield on AA rated straight corporate bonds might be 90 basis points higher. FRNs are usually benchmarked to the swap curve for the index on which their interest rates are based.

Most debt instrument front-office systems include the facilities to track individual issues to a benchmark bond issue or benchmark interest rate in this way. If the firm has a dedicated risk management department (section 24.1.5), then this department will monitor the accuracy of the sources of bid and offer prices that the firm is using, and the assumptions about benchmark issues that are used as reference points.

Alternatives to using weighted average price

The weighted average price method of calculating P&L is probably the most widely used method of calculating P&L and valuing positions, but there are other methods that may be used, including:

- FIFO (First-In-First-Out): In this method of P&L calculation, the 12 000 shares that were sold at 11am are deemed to comprise the 10 000 bought at 9am and 2000 of the 10 000 shares bought at 10am. This method is not widely used because of its complexity – it needs a history of the price of every trade that has taken place since the position last went flat, which could, in theory, be many years ago.

- LIFO (Last-In-First-Out): In this method of P&L calculation, the 12 000 shares that were sold at 11am are deemed to comprise the 10 000 bought at 10am and 2000 of the 10 000 shares bought at 9am. Firms such as private client stockbrokers that handle investments on behalf of UK resident private individuals will need to take into account the investor’s liability to pay capital gains tax if and when investments are sold. Note that UK tax law requires them to use the LIFO P&L method when calculating liability to pay this tax.

Marking swap transactions to market

Swaps are marked to market by calculating their present value (PV). The present value of a plain vanilla (i.e. fixed rate for floating rate) swap is calculated using standard methods to determine the present value of the fixed side and the floating side. The steps in the computation are as follows:

1. Calculate the present value of the fixed side. The value of the fixed side is given by the present value of the fixed coupon payments known at the start of the swap, i.e.:

![]()

where:

- C is the swap rate

- M is the number of fixed payments

- P is the notional amount

- ti is the number of days in period i

- Ti is the basis according to the interest calculation method

- dfi is the discount factor.

2. The value of the floating side is given by the present value of the floating coupon payments determined at the agreed dates of each payment. However, at the start of the swap, only the actual payment rates of the fixed side are known in the future, whereas the forward rates (derived from the yield curve) are used to approximate the floating rates. Each variable rate payment is calculated based on the forward rate for each respective payment date. Using these interest rates leads to a series of cash flows. Each cash flow is discounted by the zero-coupon rate for the date of the payment; this is also sourced from the yield curve data available from the market. Zero-coupon rates are used because these rates are for bonds that pay only one cash flow. The interest rate swap is therefore treated like a series of zero-coupon bonds. Thus, the value of the floating side is given by:

![]()

where:

- N is the number of floating payments

- fj is the forward rate

- P is the notional amount

- tj is the number of days in period j

- Tj is the basis according to the day count convention

- dfj is the discount factor.

The discount factor always starts with 1. It is calculated as follows:

[Discount factor in the previous period]/1 + [(Forward rate of floating side asset in previous period * No. of days in previous period/360 or 365)]1

3. The fixed rate offered in the swap is the rate which values the fixed rates payments at the same PV as the variable rate payments using today’s forward rates, i.e.:

Therefore, at the time the contract is entered into, there is no advantage to either party, i.e:

![]()

Thus, on the value date of the start leg the swap requires no upfront payment from either party. During the life of the swap, the same valuation technique is used, but since, over time, the forward rates change, the PV of the variable rate part of the swap will deviate from the unchangeable fixed rate side of the swap.

The daily mark-to-market accounting entry is the sum of

![]()

Accounting entries for mark-to-market activity

Tables 23.4 to 23.6 show the accounting entries to be posted in the general ledger for mark-to-market profits. If the process results in a loss, then the signs are reversed.

Table 23.4 Posting entry for unrealised profit on securities and listed derivatives

Table 23.5 Posting entry for unrealised profit on FX position

Table 23.6 Posting entry for unrealised profit on swap transactions

Securities and listed derivatives

Each individual position within each book for which the firm holds a position, the entry shown in Table 23.4 should be passed.

Foreign exchange positions

Each currency within each book for which the firm holds a position, the entry shown in Table 23.5 should be passed.

Swaps

Each outstanding swap contract for which the firm holds a position, the entry shown in Table 23.6 should be passed.

23.9 ACCRUAL OF INTEREST

When a firm enters into any of the following types of transactions:

- Purchase or sale of bonds

- Stock borrowing, lending and repos

- Money market loans and deposits

- Swaps

it needs to account for the interest that will be paid on the next coupon date of the bond or the termination date of the other types of contract. This process is known as interest accrual.

Accrual is an accounting term. It is defined as a method of accounting in which each item is entered as it is earned or incurred regardless of when actual payments are received or made.

Accrued interest is defined as the interest that has accumulated on a transaction since the last interest payment date or start date, up to but not including the current date.

23.9.1 Example of accrued interest calculation

On trade date 5 March 2007, value date 7 March 2007, ABC Investment Bank borrowed GBP 1 000 000 for 30 days at 5% interest; calculated on the actual/actual basis. The maturity date is therefore 6 April 2007.

On 6 April, ABC will repay the principal amount of GBP 1 000 000 + 30 days’ interest: Repayment amount = 1 000 000 + (1 000 000 * 30/365 * 5%) = GBP 1 004 109.59.

However, as part of the mark-to-market process ABC needs to account for this interest expense on each day that it occurs – not all in one amount at the end of the loan period.

The firm is therefore required to process the interest accrual amounts shown in Table 23.7 on each working day between 7 March and 6 April, so that the interest cost is recorded in the general ledger on the day that it is incurred.

Table 23.7 Daily interest accruals

The following business rules apply to interest accruals:

1. It is the convention that no interest is payable or receivable on the start date of a transaction, but it is payable for the end date. For money market loans and deposits the practice is to accrue interest from (and not including) the value date of the start leg of the transaction to (and including) the effective date of the accrual. For bonds, the practice is to accrue from (and not including) the date of the start of the current interest period to (and including) the effective date of the accrual.

2. For bonds, the accrual is based on the value dated position (according to the stock record used).

3. When making an accrual it is necessary to use the correct interest calculation method for the currency or debt instrument concerned. The different methods were examined in section 3.2.

4. Most financial sector firms have their statistical month ends on the same day as the calendar month end, and most systems that are concerned with interest accrual do not run at weekends.

5. Because of item (3), the daily accrual convention is one day’s interest on Tuesdays through Thursdays, and three days’ interest is to be accrued on Fridays, unless any or all of the days of the weekend following fall into the next month. If that is the case, the system should accrue to the month end date – Saturday 31 March in this example. The date that is used is the effective date of the accrual.

6. On Mondays, the practice is to accrue interest from the previous day, or from the start of the month, whichever is earlier. Hence if three days’ interest (to Sunday) had been accrued on the previous Friday, then one day’s interest would be accrued on Monday; if two days’ interest (to Saturday) had been accrued, then two days’ interest would be accrued on Monday; and if only one day’s interest had been accrued on Friday, then three days’ interest would be accrued on Monday.

Therefore, if the firm had a financial month end of Saturday 31 March, then the firm would account for the total interest of GBP 4109.59 as:

- 24 days – GBP 3287.67 forming March expenses; and

- 6 days – GBP 821.92 forming April expenses.

The daily interest accruals for the example transaction are therefore as shown in Table 23.7.

23.9.2 Accrual and de-accrual

In practice, most applications that accrue interest will, each working day:

1. De-accrue (i.e. reverse) any interest that was accrued the previous day

2. Accrue interest from the relevant start date to the relevant effective date.

In other words, in the example transaction, on Friday 9 March the application would reverse the previous day’s accrual of GBP 136.99 and re-accrue GBP 547.95, instead of accruing an additional GBP 410.96. The reason that most applications work in this way are:

1. This methodology allows for the automatic correction of any processing errors. For example, if this money market transaction had been entered into the system with the wrong interest rate, principal amount or interest calculation method, and the transaction had not been corrected until 9 March, then the process of de-accruing automatically corrects any consequent interest mispostings.

2. On the maturity date, it is not in fact necessary to make an accrual, because on this date the firm will actually pay (in this example) or receive (if it were a loan placed instead of a deposit attracted) the interest for the entire transaction. If the accrual were not reversed, then the interest expense would be duplicated in the profit and loss account. This point is illustrated in Table 23.8 for the accounting entries for the month of April that would be passed in the firm’s general ledger account for interest expense for the example transaction.

Table 23.8 Interest P&L account postings

23.10 OTHER ACCRUALS

Dividends and corporate action proceeds can also be accrued, but such accruals cannot be made before the record date for the dividend or corporate action concerned.

23.11 RECONCILIATION

Reconciliation is the process of proving that the firm’s books and records are accurate. It is an essential tool in controlling operational risk, in particular the risks caused by operational errors, as well as the risks of internal and external fraud. For this reason, the UK FSA recommends that reconciliation is usually carried out by persons who have not played any role in processing the transactions.

External reconciliation is the act of reconciling data such as cash movements on nostro accounts and stock movements on depot accounts with the settlement agents that operate those accounts on the firm’s behalf.

Internal reconciliation is the act of reconciling data held in one of the firm’s business applications (such as its settlement system) with data held on one or more of its other business application systems.

23.11.1 External reconciliation

Each firm needs to decide what information it needs to reconcile with third parties such as exchanges, central counterparties and settlement agents, but the following are the minimum requirements that apply to all firms:

- Bank reconciliations – with settlement agents and other banks that service the firm.

- Depot reconciliations – covering all depot positions for which the firm is responsible, i.e. both its own proprietary positions as well as any client positions that it may be responsible for. The regulators in most countries have specific rules that require firms to reconcile client assets.

Bank reconciliations

The purposes of a bank reconciliation are to ensure that:

- All the receipts and payments that the bank customer has posted to its general ledger account are reflected by the bank that is providing the account

- There are no entries on the bank statement that were not expected

- The balance of the account in the ledger – open transactions in the ledger and open transactions in the statement – is equal to the balance of the account on the bank statement.

In high volume financial institutions, bank reconciliations are usually performed daily. The bank that is providing the account normally sends the statement in electronic form and the statement is then passed to a dedicated reconciliation application that compares it with data provided by the appropriate internal system – usually the main settlement system. Section 23.11.3 provides more details about how these applications work.

The relevant SWIFT messages for bank reconciliation are the MT940 and the MT950. The MT950 message was examined in section 11.1.3. The difference between the two forms of statement is that the MT940 provides a longer narrative tag. The equivalent data needs to be extracted from the appropriate internal system (either the main settlement system or the corporate general ledger) so that the two sets of records may be compared.

When extracting balance data from the general ledger it is important that the value dated balance is used and not the forward balance, and that only account postings that have reached value today or earlier are extracted, or else the data that is extracted will include items that have not yet been posted by the external party. Refer to section 14.3.3 for an explanation of the difference between the trade dated balance and the value dated balance.

In a bank reconciliation, both the account balances and the individual transactions are compared. There may be many transactions of the same amount on the same day, and the aim of the reconciliation is to “tick off” the correct transaction in the internal record against its external equivalent. Consider the example shown in Table 23.9.

Table 23.9 Bank reconciliation – all items

All the items that are shown on both sides of the reconciliation, which have the same amount, reference number and value date, are “good matches”. The importance of the unique reference number was examined in section 12.2.7. If we use automated reconciliation software to eliminate the good matches, we are left with the items shown in Table 23.10, which require user inspection.

Table 23.10 Bank reconciliation – unmatched items

Depot reconciliation

The purposes of a depot reconciliation are to ensure that the firm’s record of the depot position is the same as that of the institution providing the depot account. In addition, some firms will also wish to reconcile and compare the values of any unsettled instructions with the depot institution.

In high volume financial institutions, depot reconciliations are usually performed daily. The bank that is providing the account normally sends the data in electronic form and the statement is then passed to a dedicated reconciliation application that compares it with data that is provided by the appropriate internal system.

The relevant SWIFT messages for depot reconciliation are the MT535 (Statement of Holdings), MT536 (Statement of Transactions) and MT537 (Statement of Pending Transactions). The equivalent data needs to be extracted from the appropriate internal system (usually the main settlement system) so that the two sets of records may be compared. Firms that use a stock record would extract the data from the stock record and make the comparisons in the following manner.

- Balance information: This is found by extracting all the depot balance records from the value dated stock record and comparing it to the data on the MT535 messages from each settlement agent.

- Transaction information: This is found by extracting all the individual stock record entries of the day and comparing them to the entries shown on the MT536 messages for each settlement agent. In order to perform this reconciliation, the unique reference number described in section 12.2.7 is used to link the two record sets.

A potential problem within depot reconciliation is that most settlement agents identify securities in their messages by ISIN code. In section 10.4.1 it was pointed out that where securities are traded in more than one market, there is only one ISIN code allocated to that security, but that single ISIN code may be used by more than one unique instrument in the firm’s internal records. This can lead to ambiguity, where, for example, an MT535 message is quoting the ISIN code of Sony Corporation shares, but the firm has perhaps four or five unique instruments with that ISIN code, depending on which markets Sony shares are traded and in which currency the shares are quoted.

23.11.2 Internal reconciliation

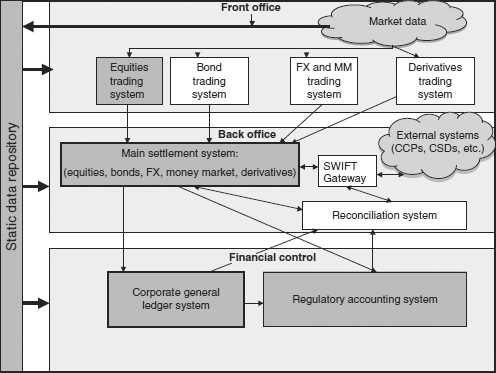

The purpose of internal reconciliation is to ensure that data that is represented in more than one business application is represented consistently across all those applications. Consider the affect of a single equity principal trade being executed and settled in the applications in the configuration diagram in Figure 23.6.

Figure 23.6 Flow of an equity trade through the configuration

The elements of this trade shown in Table 23.11, and the position that results from it, will be represented in the applications coloured in grey in the figure.

Table 23.11 Flow of an equity trade through the configuration

| Application | Trade elements | Position elements |

| Equities trading system | Nominal amount Principal value Trade price Fees such as stamp duty Consideration |

Trade dated position Value dated position |

| Settlement system | Nominal amount Principal value Trade price Fees such as stamp duty Consideration Settlement (cash) amount Settlement (stock) amount |

Trade dated position Value dated position Settled position Depot position Bank account balance |

| Corporate general ledger | Principal value Fees such as stamp duty Consideration Settlement (cash) amount |

Bank account balance |

If these amounts are not consistent across the applications, then the firm may be exposed to operational risk, as users of the systems that are showing the incorrect data will base decisions on that data. Therefore each firm has to decide which trade and position elements it needs to reconcile between applications. Making such decisions may be one of the responsibilities of the centralised risk management department, which is discussed in Chapter 24. The equivalent data needs to be extracted from the appropriate internal systems so that the two or more sets of records may be compared.

23.11.3 Reconciliation software applications

There are a number of specialised reconciliation packages on the market that perform automated internal and external reconciliations of both cash and stock. The components of such systems usually include:

1. The ability to process the relevant SWIFT messages required for reconciliation

2. Defined APIs to extract equivalent data from internal systems

3. The ability to define data relationships between systems, e.g.:

- The general ledger account code 123456 is the same entity as the nostro account number 654321 with JP Morgan

- The depot account code “Euroclear Main” in the stock record is the same as the depot account number 77665544 with Euroclear

4. A security cross-reference table that provides a cross-reference between the ISIN code used by most external agents and the internal identifiers of each security

5. The ability for users to create business rules that the system will use to match transactions on combinations of data fields such as amount, value date, description, reference number, etc.

6. The ability to display items that cannot be matched automatically and for users to manually match them and investigate them

7. The ability to escalate items that are user defined thresholds such as transaction age and transaction size.

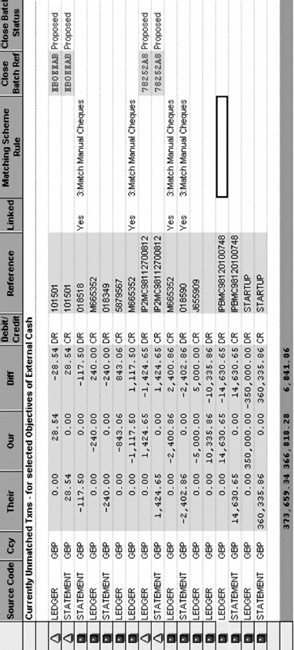

Figures 23.7 and 23.8 are provided by City Networks Limited and reproduced with their permission, in order to show some of these abilities.

Figure 23.7 Reconciliation business rules development.

Reproduced by permission of City Networks Limited.

Figure 23.8 Reconciliation user interface for manual matching and investigation.

Reproduced by permission of City Networks Limited.

Figure 23.7 shows a user developed business rule. The problem that it is designed to solve is that the one application provides cheque numbers as unique reference numbers with six digits (e.g. 005645) while the other one does not provide leading zeros. In order for the transactions to match on reference the data supplied by the second application must be manipulated to be presented in the same format as the first application.

Figure 23.8 shows a list of the items in a bank reconciliation that could not be automatically matched. Users are able to work through this list and either:

- Manually match some items for which their was not an appropriate business rule

- Propose matches for another senior user to approve or

- Commence investigation and follow-up of unmatched items that cannot be explained.

The different symbols in the first column show the status of each item. Items with the rectangular symbol are currently unmatched, while items with the triangular symbol have been proposed as matches, and await approval from another user.

1 The divisor of 360 for all currencies except GBP and JPY which use the 365-days convention. Refer to section 4.1.1.