With every new hire, an organization acquires that new employee's knowledge, which may include knowledge that is completely new to the organization and very valuable. But while the organization acquires this knowledge asset, it also takes on the employee's knowledge vacuum of job-specific operational knowledge. To fill this vacuum, organizations attempt to teach, train, and mentor their new hires and, thus, to inject new employees' existing knowledge bases with the job-specific operational knowledge they need to attain high productivity levels quickly. It is in this process of knowledge transfer (from the organization's standpoint) and knowledge acquisition (from the new employee's standpoint) that continuity management makes a major contribution.

"In every new job I start," confessed a midlevel manager, "I encounter the 'freshman effect.' The freshman effect occurs when the knowledge I have depended upon for success is no longer relevant, and I enter a condition of job ignorance. Job ignorance, however, is not an acceptable state. Not to me because I don't like to appear foolish or inept, and not to the organization because I don't appear productive. So what happens? I counter the freshman effect by attempting to pass as a 'senior,' which is what many organizations ask their new hires to do. They expect you to perform like a senior, but with a freshman's knowledge. It doesn't work. Only once have I ever been hired by a company that honored its freshmen by respecting their ignorance and offering them knowledge. It was the most exhilarating experience of my working career. It may also have been the most productive."

The lower productivity level of new hires is commonly recognized, of course, as is its cost to the organization. It is also commonly recognized that lower productivity results from inadequate operational knowledge. The increase in knowledge and experience that allows employees to increase their productivity over time has been depicted in a graph known as the learning curve. The learning curve was developed by the Boeing Company in the 1930s as a method for predicting the cost of building new aircraft (Anthes, 2001, p. 42). It illustrates the effect of improved productivity, over time, on the unit cost of production. Hence, the graph relates unit cost to time and productivity.

Boeing discovered that the unit cost dropped for each aircraft built after the first aircraft. Furthermore, it dropped at a predictable rate. With each subsequent aircraft, employees learned to work faster, make fewer mistakes, and waste less material until they reached a point of maximum productivity. The increased speed and improved accuracy of these employees resulted directly from their acquisition of operational knowledge. The learning curve of Boeing's aircraft workers was plotted as a graph, with the x (vertical) axis showing the cost of production and the y (horizontal) axis showing the units of production, as illustrated in Figure 4.1.

The steeper the negative slope of the curve (the faster the curve falls), the faster the unit cost of production falls. Boeing created the learning curve to predict the cost of future aircraft production based on early production data. This learning curve is a critical forecasting tool in manufacturing industries because it allows a company to predict its break-even point, how much cash it will consume to reach breakeven, and how much profit it will make thereafter at a given price for each unit produced. Although the learning curve is essential in estimating production costs and in setting product prices, it can be used analogously in nonmanufacturing industries to describe the learning process that occurs on any job. Employee efficiency and effectiveness improve over time as a result of on-the-job experience that increases employee and organizational knowledge and hence produces employee and organizational learning. The importance of the learning curve is its recognition that on-the-job knowledge acquisition improves efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity.

The Boeing learning curve was very much a product of the Industrial Age, but it still has its use in manufacturing. The curve's original purpose in the 1930s was to predict the unit cost of producing something, a purpose it retains. The direction of the curve emphasized that it was a reduction in the cost of the manual labor required to produce a product that was important. Therefore, lower (and falling) learning curves were preferable to higher (and rising) learning curves because they meant lower costs from on-the-job learning. But people intuitively think of knowledge and learning as something that should be increasing, not decreasing. Ironically, Boeing's learning curve went down when learning went up. The counterintuitive nature of the Boeing curve resulted in the popularization among managers of a different kind of learning curve: one that rose with learning—that is, with the acquisition of job-critical operational knowledge.

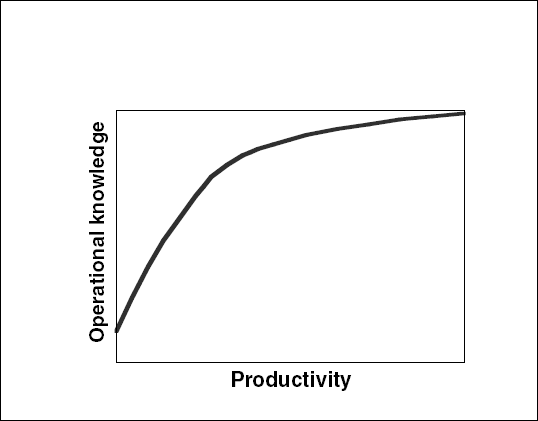

This new learning curve for the knowledge economy might be called the knowledge learning curve. It is a curve that managers and executives frequently talk about and use as a common frame of reference, even though, as far as we know, it has not technically been described before its appearance in this book. The knowledge learning curve can be graphed as illustrated in Figure 4.2.

While the knowledge learning curve takes the same concept of learn-ing over time as the Boeing curve, it applies that concept to increased productivity rather than to a drop in the unit cost of production. The knowledge learning curve depicts the increased productivity that develops as a function of the acquisition of critical operational knowledge. It illustrates the relationship between operational knowledge and productivity and between learning and productivity gain. As opposed to the learning curve, the knowledge learning curve starts on the x axis at a point near the y axis and rises with the acquisition of knowledge. The desired slope is positive rather than negative. The steeper the slope, the more desirable it is, because it indicates more rapid acquisition of operational knowledge and hence greater productivity.

With the knowledge learning curve, the objective is to move up the curve, because the higher the point on the curve, the greater the operational knowledge acquired and the higher the productivity. When executives say that they hope the learning curve isn't too steep, they mean that they hope the new employee doesn't have to acquire too much operational knowledge to get up to speed. When executives say with pride that new employees are quickly moving up the learning curve, they mean that the new hires are acquiring operational knowledge and proficiency at a rapid pace, which is bringing them quickly up to speed and high productivity.

The knowledge learning curve is not intended to be specifically predictive (as was the original learning curve in projecting actual per-unit costs), but descriptive of a process and predictive of a trend line. In theory, each new hire would have his or her own knowledge learning curve, a unique curve shaped by the characteristics of the job and by those of the new hire assuming it. Some employees might start higher on the curve and others might have a steeper curve, but the general shape of the curve should be something like the one shown in Figure 4.2.

Interestingly, the slope of the knowledge learning curve can be negative (the curve falls rather than rises). When the knowledge learning curve is dropping, it means that negative learning is taking place. Performance, of course, is deteriorating, and productivity is falling. The slope of an organizational learning curve is negative when organizational "forgetting" occurs, meaning that the organization is actually "unlearning." An unlearning organization will know less tomorrow than it did today. Organizational unlearning occurs on the micro level whenever an employee leaves and that employee's operational knowledge has not been harvested for transfer to the successor. It takes place on the macro level when knowledge discontinuities from downsizing or high employee turnover creates a net loss in the organization's knowledge base. Knowledge depletion from organizational forgetting can afflict a department, a business unit, or an entire organization, leaving the knowledge base in shambles and the organization vulnerable.

The knowledge learning curve illustrates a central point: new-employee (and, ultimately, organizational) productivity is a function of the amount of operational knowledge available to new employees and the rate at which that operational knowledge can be acquired. This relationship between operational knowledge and productivity powers the potential of continuity management to create significant competitive advantage. If increased operational knowledge is equal to increased productivity in the early phases of a new job, then the more operational knowledge available to a starting employee, the higher that employee's productivity will be from the beginning and the shorter will be the time necessary to reach maximum productive capacity (everything else being equal).

Another way to express this principle is to say that knowledge continuity makes it possible to move up the learning curve at a faster rate. The knowledge learning curve explains the powerful effect of continuity management on productivity. Because continuity management increases the amount of operational knowledge transferred to a new employee and the rate at which that transfer occurs, an organization that employs continuity management will suffer less productivity loss from retirements and recurring job turnover than one that does not. The more critical operational knowledge is to an employee's performance, the greater will be the negative impact on productivity of that employee's departure. When organizations hemorrhage knowledge from departing employees whose operational knowledge has not been transferred to their successors, they hemorrhage productivity.

Just 1 additional hour of productivity per employee per day adds up to an average of 220 hours of additional productivity per employee per year. Assuming that it takes about a year to become fully productive in a new job, the annual effect of a daily 1-hour productivity gain on the organization's performance is impressive. When this gain is multiplied by the number of replacement employees hired each year, the cumulative effect on an organization can be substantial. In a firm with an annual turnover of 100 employees earning salaries and benefits averaging $45 per hour, a net increase in productivity that generates just 1 additional hour of productivity per day equals about $1 million per year of productivity gain. The value of that productivity increase, however, is even higher because the revenue derived from employee production is greater than the cost of production once the employee has passed the break-even point.

But the productivity gains are still greater than these figures suggest. Because new employees disrupt the productivity of their coworkers until they have acquired the operational knowledge they need to become productive, the sooner they reach full productivity, the sooner their coworkers' productivity will be restored. Hence, the value of operational knowledge that raises a new employee's productivity level is greater than the value of the employee's productivity itself. It also includes the value of the increase in coworker productivity that would otherwise have been lost because of the new employee's interference with the coworkers' productive capacities.

In addition to the added productivity of the new hire and the restoration of coworker productivity levels, there is a third source of increased productivity from rapid knowledge acquisition and application. That source is group synergy. Through synergy, the group's knowledge learning curve is greater than the sum of its individual curves. Therefore, the sooner new employees can achieve meaningful productivity, the sooner they can make a contribution to the group's synergy, which raises the whole group's productivity level. By the same token, the loss of a valued employee can have a greater negative impact on the team's total productivity than the loss of one employee might suggest. In this case, the positive effect of synergy turns negative. The faster that synergy can be reestablished, the sooner its productivity contribution to the group and its members can be restored. Lost productivity cannot be made up. Like an unsold seat on an airplane flight, the profit generated by the employee is lost, and, like the fare for the empty seat, it cannot be recouped. It is gone forever.

A new group member—no matter how capable—creates negative productivity for the group in the first few weeks. Negative productivity occurs because the new group member lacks the necessary knowledge to contribute to the team's productivity, while draining productivity from other group members, who are distracted from their primary work by their attempts to orient and instruct the new employee. If the new member's period of service is relatively short, his or her positive effect on productivity may never exceed the initial negative effect, and so the new employee may never have performed productive work for the organization. Indeed, the employee will have drained productive work from the group and the organization.

A new employee's journey up the learning curve can be one of increasing exhilaration or of crushing frustration—or something in between. One of the single most important factors in determining a positive or a negative outcome is the employee's access to job-critical operational knowledge. When new hires start out, they confront a series of knowledge-based problems that stand between them and peak performance. It is the organization's responsibility to provide them with the operational knowledge they need to solve those problems and become productive.

Knowledge acquisition is not a random process. It occurs in recognizable phases. Research confirms the conventional wisdom that the productivity of new employees begins at a low level, increases over time, and finally plateaus as employees come to understand the job and bring their knowledge and competency to bear. This journey up the knowledge learning curve can be described conceptually in terms of four phases of increasing productivity—orientation, assimilation, productivity, and high performance—and a fifth phase of productivity decline that occurs as an employee prepares to leave the organization. Although the phases can be described as if they were discreet, they actually form a continuum. The length of time an employee spends in each phase depends on a variety of factors, such as intelligence, motivation, competency, and job complexity. But the key element on which all these factors act is the amount of operational knowledge transferred to the new employee.

The five productivity phases provide a framework for understanding productivity and the role of operational knowledge in achieving it. They can help new hires appreciate the limitations imposed on their performance by the knowledge learning curve, gauge the validity of performance expectations placed on them by others (as well as by themselves), and mark their progress along the productivity curve through recognizable achievements that characterize each phase. An understanding of the phases helps a new employee ask the right questions and seek the right answers. An appreciation of the phases breaks the journey up the curve into manageable segments, so that a new employee's motivation is not impaired by undue frustration or self-perceived failure. Indeed, success in each phase can provide motivation for moving to the next phase. By designing short-term wins into the early productivity phases, an organization can motivate its employees, reduce their stress, and speed their passage to high performance.

The phases of productivity are based on how operational knowledge in that phase is acquired by new employees and applied to increase their competency and improve their productivity. Several caveats are warranted regarding these phases.

First, there is no set timetable for the phases; their occurrence is dependent on a number of highly variable organizational, situational, and individual factors. The moment at which an employee can be said to enter a new phase does not depend on the passage of time per se, but on the level of productivity achieved. The phases, in other words, are productivity-dependent, not time-dependent.

Second, in an ideal scenario, employees progress through the first three phases into the fourth phase of high performance. But such is not always the case. Employees may get stuck in an earlier phase and never advance beyond it. Or they may leave the organization before reaching the high-performance phase.

Third, the lines of demarcation between the phases are subjective, fuzzy, and often difficult to determine other than in a general sense. In part, this is due to the fact that productivity is a complex phenomenon encompassing many complicated subtasks and affected by many interacting factors. At any given time, an employee might be in the orientation phase in one part of his or her work, in the high-performance phase in a second, and in the productivity phase in a third.

Finally, there is a window of opportunity in the early phases of productivity when a new employee's feedback becomes critical to the organization and should be solicited and honored. This feedback is important for two reasons:

It allows the organization to better respond to the employees' learning needs.

It encourages employees to suggest innovative procedures, policies, approaches, and solutions based on their fresh perspective before that perspective is extinguished by organizational pressures to conform. New employee feedback is an important source of creative ideas that lead to increased productivity and refinements in processes, products, and services.

"The objective," says Major General Michael McMahan, commander of the U.S. Air Force Personnel Center, "is to give everyone the opportunity to excel. You can't do that unless you also give them knowledge and unless you give it to them in an organized way" (McMahan, 2001).

The orientation phase begins on the first day of employment as new hires start the process of assimilating a formidable amount of job-related data, information, and knowledge. New-employee productivity is low, and the productivity of established coworkers is adversely affected. Experienced employees are distracted from their primary tasks by the dependency of the new hires and the need to answer their questions or otherwise instruct them.

This phase generally includes formal and informal orientation sessions that introduce new employees to the organization and to the objectives, resources, skills, procedures, activities, performance measures, best practices, and so forth associated with their jobs. Special skills training, if required, begins in this phase. The more comprehensive and personalized the orientation, training, and knowledge-acquisition program, the more likely it will be to increase the new hires' productivity.

Continuity management provides the structured, job-critical operational knowledge that enables employees to progress quickly from the low productivity of the orientation and assimilation phases to the high productivity of the productivity phase. Without continuity management, new employees' progress in the orientation phase will be difficult and halting, as the novices struggle to figure out what knowledge they need and then how to acquire it. The vast reservoir of data, information, and knowledge in contemporary organizations is meaningless to newcomers without an organized means to sort through the overload. Continuity management is a Rosetta stone for interpreting and selectively accessing this ocean of information, helping new hires determine what they need to know, based on their needs and priorities. Metaphorically, continuity management is a Geiger counter that allows new employees to identify the "radioactive" knowledge they need and to find it in the knowledge landscape.

Continuity management makes it possible for new employees to exploit fully the existing knowledge management capabilities of their organization. Critical operational knowledge provided by the predecessor acts as an organizing framework, much like an index or catalog, that enables successor employees to identify and access the additional knowledge they need through existing knowledge management tools. Continuity management equips new employees with the operational knowledge their positions require by answering such questions as: What do I need to know? How can I find out what I need to know? And how can I find out what I don't know that I need to know?

EMC Corporation uses a knowledge management tool that it calls My Sales Web, which is an internal Web site for salespeople, directed toward their day-to-day needs. My Sales Web is a repository of product information, competitor analyses, training opportunities, how-to-sell techniques, best practices, productivity tools, solutions to specific sales problems, market news, late-breaking bulletins, and so forth. Its focus is on the practical and the successful. My Sales Web provides salespeople with a macrounderstanding of the corporation, its market, and its competitors as well as direct access to detailed information on the micro level. The site is refreshed continually and accessed frequently throughout the day by each salesperson.

My Sales Web could form the basis for a sophisticated continuity management system. By combining its existing data, information, and knowledge with job-critical operational knowledge transferred by predecessor employees, My Sales Web would deliver comprehensive knowledge continuity and knowledge creation capabilities to knowledge workers at EMC. It would link the operational knowledge captured by continuity management to the expanded knowledge captured by knowledge management, integrating the two into a seamless whole of guided knowledge acquisition and creation.

During the assimilation phase, employees become familiar with their jobs and begin to get a handle on them. They have progressed from the absorption of data and information to the acquisition of knowledge and competence. They are no longer a significant drain on organizational productivity, because their knowledge and productive capacity have reached the point that coworkers no longer have to do part of their job or spend significant time instructing them. Yet, the new employees are still not making major productivity contributions. Nonetheless, the insights, lessons learned, contacts, and knowledge analyses provided by continuity management form the basis for a quick ascension to the next phase: productivity.

A window of opportunity exists in the assimilation phase during which to harvest new employees' insights, perspectives, and ideas and, when appropriate, incorporate them into organizational operations. It is easy—perhaps inevitable—for established employees to accept the status quo, buy into how things are done, and fall into a rut that is resistant to challenge and change. Recent hires in the assimilation phase are not yet in that rut. They retain an outsider's perspective on their job that can now be integrated with an insider's understanding of that job's parameters, demands, and opportunities. This integration uniquely positions them to make objective judgments about the effectiveness of the status quo. From such judgments come innovation, increased productivity, and new ideas that keep the organization responsive and sharp—but only if the organization listens. Once new hires have been fully acclimated to their positions and have entered the productivity phase, they will be less likely to challenge basic assumptions or to propose new ways of doing things. As their routines become established and powerfully influenced by peer pressure and organizational culture, they will find it increasingly difficult to think outside the box that the organization is constructing around them. The pressures for conformity will be too strong.

Because a new hire's challenge to the status quo may be perceived as a threat and met with resistance, a formal mechanism needs to be established in this phase to encourage innovations, challenges to the status quo, and suggestions for change. Such a mechanism will ensure that the new employee's ideas are heard, evaluated, and acted on by adoption, modification, or rejection (with reasonable cause). This process of incorporating new insights and fresh perspectives into an organization's operational knowledge pool is the means by which knowledge continuity leads to excellence rather than to mediocrity. Through the infusion of new knowledge, employees create knowledge to add to the knowledge base to which they are heir, steward, and contributor. This challenge to the knowledge pool ensures its revitalization and therefore its currency and its value. There is nothing sacred about operational knowledge; it is always subject to change as the conditions in which it is relevant change. In the Information Age, the competitive edge belongs to those who take advantage of this potential to invigorate the knowledge pool.

In the productivity phase, new employees convert the knowledge acquired in the orientation and assimilation phases into job-specific competencies that produce productivity gains for the organization. They are no longer net consumers of knowledge; they are producers. Knowledge of effective practices, critical cause-and-effect relationships, crucial knowledge networks, key resources, lessons from past failures, and an expansion of skills create the productivity levels that characterize this phase. Effective problem solving, sound decision making, and innovative solutions are the result. The phase is also marked by a strong motivation to add to existing knowledge, to build on previous successes, and to produce impressive operating results. Using a sports analogy, the phase begins with the new recruit on the bench, insisting, "Hey, Coach, put me in the game." It ends with the recruit saying, "I'm in!"

In the high-performance phase, employees are at the top of their game, and exceptional productivity occurs. Elevated synergy levels, extensive operational knowledge, broad knowledge networks, comprehensive exchanges of knowledge in communities of practice, and cohesive groups all contribute to extraordinary performance. The commitment of these high performers to innovative approaches and creative solutions generates improved procedures, processes, products, and services. These employees create new knowledge at an accelerating rate, and they increase the productivity of others through the operational knowledge they share.

Since the level of productivity achieved in the high-performance phase depends on comprehensive operational knowledge and high levels of individual competence, continuity management's major contributions to this phase are the preservation of critical insights from generations of previous incumbents and the ongoing knowledge analysis that continuity management requires. That analysis facilitates continuous learning and skill building, more adept application of operational knowledge, and greater and greater knowledge integration.

Employees enter this phase when they decide to leave the organization or else discover that they will be forced to leave because of layoffs, terminations, or transfers. In the departure phase, motivation drops, productivity declines, quality of work suffers, and innovations cease as employees turn their attention to the next job, to finding the next job, or to retirement.

This productivity decline affects coworkers' productivity levels both because group synergy drops and because coworkers have to assume some of the work abandoned by the departing employees, perhaps even before they have left. If the departure is an angry one, or coworkers see the departing employees as having been mistreated, their productivity may also decline in response to that negative emotional reaction. Even if the departure is friendly, surviving employees will experience sadness and, to some degree, anger about the loss. All the parties affected by the departure must grieve the loss of the departing employees. Psychological and emotional withdrawal by either the departing employees or their coworkers or both may begin, defensiveness may increase, avoidance reactions may develop, and relationships will change as all parties attempt to adjust emotionally to the loss.

Continuity management's major contribution to this phase is its preservation of each departing employee's operational knowledge even if that employee's departure is on unpleasant terms. Since the operational knowledge captured by continuity management has been built up over time, it remains valuable to the organization, because its contents reflect the productivity or high-performance phases of the employee's tenure as well as the operational knowledge of previous employees in their productivity and high-performance phases.

The five phases of productivity provide a conceptual framework for understanding the process through which operational knowledge is acquired by new hires and how the acquisition of that knowledge relates to their productivity. The phases emphasize that the knowledge acquisition rate of new hires has a profound effect on productivity and organizational performance. The phases explain why high job turnover without knowledge continuity reduces the knowledge asset, impairs productive capacity, and disables high performance. Continuity management maintains the operational knowledge base between incumbent and successor employees that sustains productivity and, at the same time, enables the generation of new knowledge that adds still more productive capacity. This relationship among knowledge, knowledge continuity, and productivity is one key to deciphering the mysteries of gaining competitive advantage in the Information Age.

Effective management in the knowledge economy requires a reorientation that focuses attention on the key role of knowledge and its preservation across employee generations. Chronic knowledge loss exacerbated by baby-boomer retirements threaten corporate productivity across the economic spectrum, and the situation is worsening. Yet the negative effects of knowledge discontinuity have persisted as a blind spot in the management field of vision. A new vision, however, is replacing the old as the crisis of knowledge loss comes into sharper focus, impairs productive capacity, and casts its red shadow toward the numbers on the bottom line.