Introduction

It may be helpful to provide some context for this book by beginning with a brief summary of the discipline of security law and a description of the historical, theoretical, and situational factors that have led to our current circumstances in security and policing.

SECURITY LAW AS A DISCIPLINE

The concept of security law requires an understanding of many diverse legal disciplines. These disciplines range from negligent and intentional torts to contract and insurance provisions, agency and vicarious liability theories, and constitutional and criminal laws. Despite their obvious diversity, these disciplines are linked in this context by the impact of crime and misconduct. Hence, this legal analysis should be supplemented with “security sense” and experience.

As with any discipline or endeavor, experience in private security law is critical. In my hundreds of contract negotiations involving security matters, I have often been struck by the attorneys’ unfamiliarity with security issues and with the security industry in general. This should not surprise anyone. Indeed, attorneys, like most other professionals, typically develop a niche or an area of practice that focuses on a particular legal discipline. For example, family law attorneys focus on divorce, support, child custody, and like matters. Similarly, personal injury attorneys litigate negligent and intentional torts. In this sense, I advocate thinking about security law as a discipline.

As recently as three decades ago, there was little interest in the notion of elder law. Those who practiced family law were relegated to the category of “divorce lawyers.” Similarly, the discipline of environmental law had not yet been conceived. Since then, new legal disciplines have emerged to serve the changing needs of the marketplace and of society. Currently attorneys practice in niches devoted to the aging population, to changing family norms, and to the protection of the environment.

In post 9/11 America, the emphasis on security has been heightened. While some people continue to question the extent of the threat facing this country, those who study terrorism and security know that the threat remains real. Indeed, the threat of violence, particularly from terrorism, violent gangs, and lone psychopaths, is likely to persist. Violence is as old as human nature. I see no end to violence as long as human nature exists.

As with any trend, those who are closer to the issue see the picture with more clarity. In addressing this area of the law, I have been blessed with a rather unique set of skills and experiences. As a young police officer in the early to mid-1980s, I attended law school with the intention of focusing on public safety and security. While I did not fully realize the importance of this legal training at that time, it enabled me to be a better police officer. As a tactical police officer in the gang crime unit, I patrolled the South Side of Chicago on “missions” designed to actively seek out crimes committed by gang members. I arrested hundreds of gang members, mostly for crimes involving drugs, illegal gun possession, and violence.

My law school experience helped me understand the legal limits of my role as a police officer. It helped me grasp the legal principles surrounding search and seizure, the nuances of warrant requirements, and other police procedures. In this sense, being a good police officer requires knowledge of the law. The better a police officer understands the law, the more effectively he or she can perform the job.

The same holds true for the security professional. In many ways, the issues confronting security personnel are actually much more complicated than those facing the average police officer. Unlike the typical police officer, the security professional must be equipped to prevent as well as temper the consequences of occurrences such as workplace violence, sexual harassment, internal theft, and threats from criminals and even terrorists. Simply put, to deal appropriately with the many diverse and complex legal issues within this field, the security professional needs to possess expertise that extends beyond the rather narrow confines of criminal law.

This maze of legal issues is further complicated by the unfortunate, but inevitable, lack of consistency created by differing state laws. Unlike criminal law, which involved numerous U.S. Supreme Court decisions, the subject areas within security law are largely based on state court decisions. Because so few U.S. Supreme Court decisions relate to security law, security professionals, and their legal advisors, tend to focus much more on state laws within their particular environment. The many variations in security laws among different states present a real challenge to corporations with properties and service provisions in different states. This situation also complicates the task of developing a comprehensive book on security law.

By now some readers may be asking: Why should I care about court decisions—made by judges and juries—who have little understanding of security methods and principles? The short answer is liability. Liability often drives the implementation of security methods. Stated another way, the exposure of potential liability—often in damage awards reaching six, seven, or even eight figures—has motivated many corporations; either private, public, or municipal, to worry about security. Of course, some organizations continue to insist that it “won’t happen here.” Nonetheless, many unfortunate businesses and property owners find themselves on the wrong end of a lawsuit, faced with substantial potential exposure or actual liability. Hence, court decisions have provided substantial incentive for organizations to face the impact of crime and misconduct. The old adage of “pay me now or pay me later” has been a powerful motivator to take the threat of crime and misconduct seriously.

Let me clarify a key point. I do not advance or subscribe to the notion that security methods are directly related to liability exposure. To do so would equate life with money. This is not my intention. My point is that the legal system has shaped security methods and even, to a large degree, the security industry. This is so in a number of ways. Since the consequences of security breaches vary, or are not directly quantifiable prior to the incident, the typical property or business decision maker may believe that little or no security is sufficient. When no crime is committed, the decision proves correct. This mind-set gives rise to the inevitable questions: Why spend money on security? Why inconvenience your employees, tenants, or customers with security protocols that seem unnecessary? Coupled with the natural human tendency to believe that bad things happen only to others, this attitude leads many to assume, often incorrectly, that their environment or workplace is safe.

Now add hefty and highly publicized court decisions to the mix. At this point, many people will sit up and take notice. While some may still cling to a false sense of security, reasonable and prudent decision makers now see the implications much more clearly. The implications, of course, are more than just money damages. Loss of reputation, goodwill, business continuity, and of course, the lives and property of those affected by a workplace crime are also involved. The need to prevent such losses is a strong incentive to pay attention to security. With these implications in mind, I will provide an overview of the historical and theoretical underpinnings of this book.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES

Centuries of history related to security and policing can be summarized in one overriding human theme: survival. The security of the individual, the family, the community, and even the nation-state are all tied to this basic need. As an indicator of its importance, Maslow classifies security as a second-tier need in his hierarchy of needs, just above food, clothing, and shelter.1 Given the importance of security, it is understandable that humans have developed various mechanisms designed to foster this goal. While this summary represents only a cursory view of the historical complexities of security, the issues raised in this overview are intended to provide a pointed and appropriate framework for private security law.

For centuries, people in the community have acted as the security force within the community. Indeed, the “job” of security was not even a job. It was the duty of all able-bodied men to protect their homes and their community.2 There were no police to call. Instead, the people acted in self-defense or in defense of their community. Through much of history, security was seen as the province of the people. This viewpoint was so entrenched that it even served as one of the guiding principles of the founder of Britain’s first professional police force, Sir Robert Peel, who asserted: The people are the police, the police are the people.3

Before the formation of public police, self-help and self-protection were considered the foundations of law enforcement and public order.4 Throughout much of recorded history, kings were primarily concerned with conducting warfare and protecting their land from invaders. This changed when the legal system or the justice process came to be regarded as a cash cow.5 The subsequent expansion of the internal justice process was justified by the concept of the king’s peace. The term king’s peace equated to law and order.

As the power of the king evolved, many offenses that were previously regarded as intentional torts (wrongs subject to civil action) were deemed crimes against the king’s peace.6 Reynolds observes this key fact: “Whereas the spoils of tort law belonged to the victims, the spoils of criminal law went to the king.”7 Based on this principle, acts previously considered torts such as arson, robbery, and murder could be declared crimes. The incentive to expand the king’s peace was clear. If people could be declared criminals, their property could be confiscated by the king.8 Such declarations allowed the king to collect property or revenue from the “criminal.” Likewise, the criminal could be punished (or even executed) for deeds against the king, his sovereignty, and his people.9

The change from a tort-centered to a crime-centered system directly affected those who were to be compensated. Traditionally, the injured person (or his or her family) was to be financially compensated by the person who caused the injury. Many victims favored treating offenses as civil torts, because this provided them with a way to collect financial compensation.10 The typical compensation involved some financial or property transfer to the victim or the family of the victim from the person who caused the injury. However, once the act was declared a crime, the financial benefit through fines, confiscation of property, and the like was transferred to the king.

It is important to note, however, that this increasing expansion of the criminal law was not without justification. Those who favored increasing sovereignty of the king believed it would reduce the incidence of retribution by private citizens, as well as provide for legitimate sanctions by government.11 Government sanctions against criminals were deemed legitimate because they removed the need for the victim (or his or her family) to retaliate against the offender.

Traditional codes of family honor could lead to bloody feuds that persisted for generations. By assuming the right to avenge harm on behalf of all the people, the state (or king) also assumed the obligation to ensure swift, sure justice, as well as to protect the rights and safety of the public. This type of system promised not only to limit the scope of retributive violence, but also to transfer the costs of seeking justice to the state, while assuring victims that they could rely on state’s vast powers to redress their grievances.

The desire to limit the use of power or coercion to the government rested on sound reasoning. Naturally, there was a desire to reduce the amount of violence. Many believed that responding to violent acts based on the “eye for an eye” code of justice served only to perpetuate violence. Notwithstanding the potential for deterrence, or even the justification of retribution, the notion that government should be the arbitrator of violence had compelling logic. According to this way of thinking, putting the government in charge of retribution would help limit the use of violence by private citizens. As a consequence, government was increasingly saddled with the burden of controlling crime and capturing and punishing criminals.

Notwithstanding this gradual transfer of authority to government (or to the throne), the burden of law and order rested on the citizenry for a large part of recorded history. In early times, crime control of the town or community was provided by people through the use of the “hue and cry.”12 A hue and cry was a call to order. It was designed to alert the community that a criminal act had occurred or was occurring. Upon this call to order, able-bodied men responded to lend assistance, or to pursue the criminal. This ancient crime protection system is remarkably similar to the “observe and report” function of private security, absent the pursuit and capture of the criminal. The theory behind observe and report is that the security officer should act as a deterrent to crime. When a crime is observed, the task of the security officer is to gather information about the criminal (or the crime), and then immediately report such to the public police—in effect, serving as the “eyes and ears” of the police. 13

Over time, however, the custom of hue and cry gave way to a more defined system of crime prevention. This system, known as “watch and ward,” entailed more formalized crime prevention methods. It was headed by shire reeves appointed by the king.14 The shire reeves, in turn, appointed constables to deal with various legal matters. Both the shire reeve (later shortened to sheriff) and the constable were the forerunners of modern sworn law enforcement officers.15 This system furthered the legitimacy of public officers in crime prevention and control, with the appointment of individuals who reported directly to the king.

Early American colonies adopted this watch-and-ward system. Partly due to the deficiencies inherent in this system, however, some towns supplemented this method with night watches conducted by citizens appointed by the local government.16 Unfortunately, these unpaid, ill-trained, and ill-equipped constables often failed to control crime. As a result, businessmen hired their own security to protect themselves and their business or property.17 These early security providers, however, did not protect the general population. Most people had to fend for themselves. Towns and villages were largely unprotected, except by those who lived there.

Based on these circumstances, some criminologists and historians believe that the emergence of municipal police forces were a direct result of the growing levels of civil disorder within society.18 Indeed, Miller emphasized that in 1834, known as the “year of riots,” legislators in New York decried the need for order. This outcry for order translated into more “security” forces. It became increasingly clear that the established system of crime prevention was not working. In this sense, the riots acted as a trigger, helping to bring about the institution of municipal police departments.

The emergence of public police, as with any societal initiative, was not without its problems and detractors. Many people argued that a full-time police force was too expensive. Certainly, the traditional methods were less costly because the major portion of these protective services was provided by unpaid volunteers.19 Another economic objection was based on the argument that the newly created public police agencies were unable—or unwilling—to provide for the security needs of the commercial sector.20 To support this assertion, critics of public policing could point to the situation in America’s “Wild West.” The western territories had few government-employed police officers. This lack of police officers was especially problematic for newly developing mobile commercial enterprises, such as the railroad industry. Labor unrest, especially in the steel, coal, and railroad industries, further drove the demand for security.21 Not surprisingly, this growing need for security significantly drained resources from already overextended municipal police departments.22 In order to serve this growing market, Allan Pinkerton formed the first contracted private security firm in America.23 This occurred in 1850, at a time when many municipal police departments were in their infancy. Thus, paid security forces were developing even while the growth of public police departments was still in its early stages.

Other criticism of early policing pointed to the dangers of a government monopoly on policing,24 fearing that it could lead to the development of excessive police power.25 To these people, the cop on the beat represented an “ominous intrusion upon civil liberty.”26 To others, the concern for security overrode the integrity of constitutional provisions. Thus, the tension between the desire for security and the desire to maintain constitutional protections became critical in the debate over this policing initiative. Likewise, the difficulty of balancing public safety with individual rights continues to fuel controversy over current security initiatives—whether public or private.

As public policing began to take hold, certain legal decisions carved out the specific duties of the government in regard to the safety and security of its citizens. As noted earlier, the historical roots of policing stemmed from the notion that citizens were obligated to maintain law and order. This notion was consistent with the ideals of the framers of the U.S. Constitution. They assumed that law-abiding people would be largely responsible for their own safety.27 As a result, the framers of the Constitution did not define any specific governmental obligation to protect citizens from crime. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the principle that government does not have a specific duty to protect individuals in the famous case entitled South v. Maryland (1856). In its decision, the Court refused to create this duty based on the belief that it would “impose a crushing economic burden on government.” Instead, the Court held that government had a general duty to enforce laws, but not to protect any particular person. Significantly, the South v. Maryland Court held that:28

There is no constitutional right to be protected by the state against being murdered by criminals…. The constitution is a charter of negative liberties, it tells the state to let people alone, it does not require the federal government or the state to provide services, even so elementary a service as maintaining law and order.29

This decision provided the intellectual principle that the government is not responsible for the safety of its citizens—as it related to criminal activity. Accordingly, citizens are expected to secure their own safety from criminals, independent of the protection from government. This basic principle has not changed. Absent the duty from a third party, usually imposed on a corporation or a property owner, the burden is on each individual to provide for his or her own safety and security.30

This brief historical perspective illustrates the impact of crime on civilized society. In days of old, security was the province of the people. In contemporary times, “the people” typically pay others for protection. Citizens pay taxes for municipal policing. Clients pay contracted fees to security firms. Both of these methods of maintaining public safety and providing security services are accepted as contemporary norms. However, as will be more fully articulated later, there is a growing trend for citizens to pay security firms for protection within the public realm. This creates a sort of back to the future circumstance, where “the people” are taking more responsibility for their own security.

The payment of monies for private security services raises an important question: Is it appropriate for clients, who are citizens of a governmental entity, to pay a private firm for security, or even public safety services? My answer is yes. To answer this question for yourself, you might begin by asking yourself these questions: Is it wrong to pay for personal protection? If public police cannot or will not provide for your personal protection, is it inappropriate to pay a security firm to do so? Viewed from this perspective, affirming the individual’s right of self-defense seems the only reasonable approach.

Because the job of private security professionals involves the imminent threat of violence, their effectiveness almost inevitably depends on their ability to use appropriate tactics, including the use of force. Regardless of the situation that prompts the use of force or the mere imposition of verbal commands, the use of coercive measures is subject to monitoring by the legal system, either through judicial and legislative pronouncements. Thus, those who are in the business of security have a responsibility to stay informed about the legal limits of their power and authority. As the role of security providers in society continues to expand, the need to understand private security law becomes increasingly important. This book attempts to address that need.

CRIME, CRIMINOLOGY, AND SECURITY LAW

Security personnel seek to prevent crime by attempting to predict reasonably foreseeable crime and develop precautions against it.31 Whether a crime is foreseeable and whether it can be prevented is often based on an understanding of the environment and of the offender.

A substantial body of law has grown around the notion of the environmental aspects of crime. Many researchers believe that an area often undergoes a transition from relatively few crimes toward a high incidence of crime or a heightened fear of crime, caused in part, by lack of order.32 For example, order maintenance theories contend that crime problems initially arise from relatively harmless activities, such as drinking on the street, graffiti on buildings, and youths loitering on street corners. If these activities go unchecked, the level of fear and incivility in the area begins to rise and more serious crimes, such as gang fights or even drive-by shootings, may take place. The underlying theory is that the presence of disorder tends to reduce the social controls previously present in the area. This results, at least in theory, in the increased incidence of crime, particularly serious crime. Increased crime, in turn, contributes to the further deterioration of the physical environment and economic well-being of the community.

The development of order maintenance theories can be traced to a line of thinking that developed over time. These theories focused on conditions in cities, particularly in the slums. In these areas of the city, conditions included “physical deterioration, high density, economic insecurity, poor housing, family disintegration, transience, conflicting social norms, and an absence of constructive positive agencies.”33 Over time, researchers began to focus less attention on socioeconomic factors, and more on the physical characteristics of the community, or on the environment. The focus on the physical characteristics of the space where crime occurred resulted in a substantial body of scientific research, including that of Cohen and Felson. They argued that the completion of a crime requires the convergence in time and space of an offender, a suitable target, and the “absence of guardians capable of preventing the violation.”34 The guardians include police, security, citizens, and “place managers” who are either formally or informally responsible for a particular property or location.35

This focus on environmental factors is seen in a number of studies. For example, Gibbs and Erickson found that the daily population flow in large cities “reduces the effectiveness of surveillance activities by increasing the number of strangers that are routinely present in the city, thereby decreasing the extent to which their activities would be regarded with suspicion.”36 The implication was that the more crowded an area became, the less likely it was for strangers to be noticed. Thus, with less natural surveillance from community residents, more crime might develop. Consequently, Reppetto concluded that the social cohesion and informal surveillance declines with the large number of people living in a given area.37

Similarly, Lewis and Maxfield focused their research on specific physical conditions within the environment. They sought to assess how the environment affected the level of crime and the fear of crime. Their research design took into account such factors as abandoned buildings, teen loitering, vandalism, and drug use. They believed these factors draw little attention from the police partially because the public police have limited resources to effectively deal with these problems.38 The researchers noted that such problems, nonetheless, are important indicators of criminality within any community.

These problems are considered indicators of the “level of incivility” in an area and are thought to contribute to a sense of danger and decay. The presence of danger and decay, in turn, increases the perceived risk of victimization.39 In this sense, the presence of incivility may lead to crime, or it may simply cause an area to seem dangerous. Indeed, while some incivilities are not even criminal, they are disconcerting nonetheless. For example, groups of teens walking through a neighborhood may be legal but still raise fears within the community. As such, these studies concluded that policymakers should focus on “neighborhood level” approaches to reducing crime and fear.

This research was supported and further validated by subsequent studies. Covington and Taylor conducted research into what they termed the “incivilities model.” They argue that people perceive “cues” to the underlying level of disorder in their immediate environment. When people sense negative cues in their environment, they feel more vulnerable and fearful.40 In essence, they become more aware that they may be at risk of being criminally victimized. Consequently, cues representing incivility may serve as an early warning or an indicator that the environment may be ripe for serious crimes.

What are these cues, or the signs of crime? According to Covington and Taylor, there are several indicators or cues. They fall into two distinct categories: social and physical. Social cues include public drinking, drug use, loitering, and disturbances such as fighting and arguing. These activities may be deemed disturbing to some people, and dangerous to others. Physical cues include litter, graffiti, abandoned buildings and vacant lots, and deteriorating homes and businesses.41 While these conditions may not be inherently dangerous, they create the impression that the neighborhood is declining. This impression, in turn, may foster an attitude that the people in the neighborhood do not care about their homes or their community. As a consequence, those intending to commit crime may view the perceived lack of care as an invitation for criminal activity.

Subsequent research by Fisher and Nasar further validated this logic. They studied the effects of “micro-level” cues. Micro-level clues involve a specific place or location. The authors found that such cues relate to fear in three specific criteria:42

• Prospect—openness of view to see clearly what awaits you.

• Escape—ease of departure if you were confronted by an offender.

• Concealment—extent of hiding places for an offender

Based on an analysis of these criteria, the authors concluded that areas that lack open views and avenues of escape for potential victims while offering criminals effective hiding places are ripe for crime. When faced with these conditions, individuals tend to feel a greater exposure to risk, lose their sense of control over their immediate environment, and are more aware of the seriousness or the consequences of attack.43 This conclusion further advanced the concept of “situational crime prevention.” This approach advocates the examination of the actual criminal event or incident. When doing so, it is considered key to assess how the “intersection” of potential offenders connected with the opportunity to commit crime. This level of analysis focuses on how to prevent this “intersection” from occurring. According to this way of thinking, reducing the criminal’s opportunity to commit crime should enable individuals to avoid crime. Consequently, the commission of a particular crime could be prevented through specific measures designed to reduce the offender’s ability (or even propensity) to commit crimes at a specific location.44

The conclusions from these studies have been echoed by a number of other authors, including Kelling, who asserts that citizens regularly report their biggest safety concerns to be activities such as “panhandling, obstreperous youths taking over parks and street corners, public drinking, prostitution, and other disorderly behavior.”45 All of these factors have been identified as precursors to more serious crime. Moreover, the failure to correct these behaviors is often perceived by potential offenders as a sign of indifference—which may lead to more serious crime and urban decay.46 According to this thinking, the most effective way to reduce crime is to address both the physical and social conditions which foster criminal behavior and to prevent such conditions from festering into more serious levels of incivility and decay.

The logic behind and conclusions derived from these studies have been embraced by both public police and private security. The key component of these studies, in both the public and private sectors, is order maintenance. Order maintenance techniques are designed to improve physical conditions within a specific geographic area. This can be accomplished in a number of ways, including the rehabilitation of physical structures, the removal or demolition of seriously decayed buildings, and the improvement of land or existing buildings by cleaning and painting. Other environmental improvements, such as planting flowers, trees or shrubs, and various other methods to enhance the “look and feel” of an area are also recommended.47 These physical improvements are then coupled with efforts to reduce or eliminate certain anti-social behaviors. The reduction or the elimination of problematic social behaviors is at the core of an order maintenance approach to crime prevention. The objective is to address these behaviors before more serious crimes occur.

Viewed from this broad environmental perspective, the topic of security becomes wide ranging. It can encompass services as seemingly diverse as trash collection and private police patrols that are in fact linked by the common goal of improving conditions within a neighborhood. Given the important role of the environment in the development of crime, the need to control physical conditions and public activities within a particular environment is paramount. The advent of terrorism will only magnify this environmental focus. In today’s world, many formerly unremarkable occurrences can seem ominous. An unattended package left on a street corner might turn out to be a lethal bomb. The illegally parked vehicle in your neighborhood could be a tragedy in the making. In this new reality, the importance of an orderly and clean environment cannot be understated. Of course, these perceived or potential threats are difficult to remedy. Nonetheless, this growing emphasis on the environment has been echoed by Kaplan, who views the environment as the security issue of the early twenty-first century.48

In public policing, these order maintenance techniques are encompassed in the concept of “community policing.”49 The core of community policing is for policing efforts to extend beyond the traditional goal of crime fighting. It is to focus on fear reduction through order maintenance techniques.50In this way, crime and fear reduction through order maintenance are in accordance with the environmental theories articulated above.

This focus on prevention has traditionally dominated the decisions of security industry officials.51 Indeed, the similarity of private security techniques and community policing techniques can be narrowed to one core goal: both are intended to utilize proactive crime prevention that is accountable to the customer or the citizen.52 Private security’s traditional “client focused” emphasis on preventing crime—not merely making arrests after a crime has occurred, directly relates to this approach. With community policing seeking to achieve this same goal, the functions of police and security have or will inevitably move closer together. Of course, private security is particularly well suited to serve in a crime prevention or order maintenance role. This has been its role for generations. At least partly because of its focus on the property and financial interests of their clients, private security has long since replaced public police in the protection of business facilities, assets, employees, and customers.53 This is because private security personnel provided what the public police could not accomplish. Specifically, the industry provided services for specific clients, focusing on the protection of certain assets, both physical and human, as their primary and even exclusive purpose.

The increase in tort causes of action, known as either premises liability or negligent security, has fueled explosive growth in the security industry, and in the business of personal injury attorneys.54 These lawsuits stem from negligence based legal theories, which question whether the business or property owner knew or should have known that a criminal would come along and commit a crime within the property. Hence, the crime victim could sue the business or property owner (and indirectly its insurance company) for the actions of the criminal. The logic of this cause of action rests on the theory that the owner contributed to the crime, or at least, allowed the crime to occur by failing to take remedial action. According to this logic, the property or business owner, who did not commit the crime, is nonetheless guilty of negligence by allowing the conditions conducive to crime to occur or to fester. Thus, the failure to cure the conditions served to “invite” the criminal act.

These causes of action are based on two contemporary developments. First, the impact of crime has created substantial damage—in human and economic terms. Faced with these financial and human tragedies, courts began to develop the logic and reasoning to support these lawsuits. Second, these lawsuits were intellectually justified by the previously described body of knowledge relating to crime. This thinking was further supported by the Restatement of Torts 2nd, Section 344, which provides the crime victim (plaintiff) must prove both of the following conditions:55

1. Owner knew (or should have known) the premise was not secure.

2. Negligent features of premises allowed the crime to occur.

Scientific studies relating to the relationship between crime and the environment are compelling. As noted previously, numerous studies have provided a wealth of evidence that criminals do not act arbitrarily and randomly. Indeed, despite the public’s abhorrence of criminal conduct, criminals tend to view the decision to commit a crime as a rational choice. The offender may weigh the risk of being caught versus the benefit from the crime. If the potential gain outweighs the risk, then it is more likely the crime will occur. Based on this logic, it seems reasonable to infer that crimes tend to occur in locations that minimize the criminal’s risk of being caught while maximizing his or her advantage. Indeed, criminological research has demonstrated that certain factors may lead to crime. These factors include: disorderly conditions, diminished lighting, high prospect for escape, increased ability to conceal the crime, and various other factors related to the criminal decision process.56 Such factors may even invite crime. For example, Gordon and Brill argue that poor lighting not only fails to prevent crime, but acts as a “crime magnet.”57 For these reasons, it was not a great leap for courts to begin to accept the counterintuitive notion that the property or business owner should pay for the actions of the criminal.

A significant consequence of this thinking was to extend legal exposures to a new class of defendants: property and business owners. This exposure, in turn, became a motivator for many owners to institute security measures within and around their property or business location. In this sense, potential liability served as both a carrot and a stick. The carrot was the advantage that promised to accrue to property or business owners who established a safe and secure place in which to do business, and to live or work in. Certainly, maintaining a safe and secure environment could not hurt the reputation of the business, or the viability of the property. Conversely, the stick was substantial potential liability, with large jury awards, that could occur in the event of a crime on their property. In addition, media exposure stemming from such incidents could create a reputational and public relations nightmare for the owner of the business or property where the crime occurred. Clearly these factors provided substantial negative motivation to secure the premises from criminals.

This carrot and stick approach led to the growing use of private security personnel and methodologies. This boded well for the security industry. Business and property owners started to think and worry about security. They became more proactive in their approach to a safe and secure environment. For security firms, the need for increased vigilance created a larger and larger market of potential clients. It brought security further and further into the realm of the average citizen. Security personnel began to be routinely used at businesses and large corporations, now often focusing on the protection of employees and clients, instead of simply preventing them from stealing. In this sense, security became more mainstream. It is part of the hospital you visited, part of your workplace, and part of the apartment building you live in. Consequently, the security industry moved into the lives of average people. No longer was it just the public police who serviced the people; now there was another service provider, this one operating out of the private realm. Now private security was “the people.” This closeness to mainstream society also increased the scope of the services provided by private security.

As premises liability and negligent security lawsuits developed, the liability of business and property owners extended farther and farther beyond the “protected facility.” The seemingly ever-expanding perimeter was the result of court decisions. It was not uncommon for incidents in parking lots to create liability exposure. Indeed, liability exposure may even be claimed to apply to attacks that occur beyond the perimeters of the property or business.58 In fact, lawsuits have succeeded in cases of criminal attacks that occurred down the street from the property or business held liable. As liability exposure expanded, so did the security perimeter and methodologies. Consequently, it is now common for security patrols and hardware for properties and businesses to extend into the streets and other public areas, in the quest to prevent crime and to provide a safe and secure environment.

Conversely, public police have a much more difficult task incorporating crime prevention into their organizational structure as a result of the broader societal mission to universally enforce laws throughout society, as well as to preserve democratic and constitutional ideals. Considering that the already overburdened public police are also faced with economic and operational constraints, it is not unreasonable to conclude that the role of private security will continue to increase. This relationship between crime and security has been pointedly summarized by Thompson. In addition to the criminological theories summarized previously, he outlines the increased incidence of security liability to the following factors:59

• Increased crime

• Growth of private security

• Greater public awareness of litigation

• Greater number of attorneys

• Increased publicity about criminal incidents

CONTEMPORARY CIRCUMSTANCES

The relative size and scope of policing and security are well known in industry circles. Much of this data is derived from the groundbreaking Hallcrest studies. These studies reveal that in 1981, the security industry spent approximately $21.7 billion, compared to the $13.8 billion spent on public policing. In 1991, these expenditures rose to $52 billion for private security, compared to only $30 billion for public policing.60 By the year 2000, private security spent approximately $104 billion, while public policing spent only $44 billion.61 This ratio of expenditures reveals that about 70 percent of all money invested in crime prevention and law enforcement is spent on private security. Furthermore, statistics reveal that the annual growth rate for private security is about double the growth rate of public policing.62 Through the year 2004, private security grew at a rate of 8 percent per annum.63 Most of this growth was prior to September 11, 2001. These figures illustrate that private security is one of the fastest growing industries in the country.64

Following the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, some security firms predicted revenue growth in the range of 10 to 12 percent per year.65 One verifiable example of this growth is the increased presence of private security officers in New York City since 9/11. In September 2001, there were 104,000 security officers in New York City. By October 2003, the number of security officers there had risen to 127,006.66 This level of growth is not atypical of the expansion of the security industry in other parts of the country.

The number of security employees in relation to police further emphasizes the growing predominance of the security industry in the crime reduction arena. Consider some historical trends. From 1964 to 1991, employment in private firms increased by an astonishing 750 percent, with the number of firms providing security and investigative services increasing by 543 percent.67 Public policing agencies also grew their number of full-time sworn police personnel to about 700,000. The number of police personnel, however, pales by comparison of recent security industry estimates of 2 million people employed by security firms.68 In some urban areas, such as El Paso, Texas, the number of private police is estimated to exceed that of public police by a ratio of 6 to 1.69

The growth of private security is reflected in recent financial and hiring data from two huge international firms that dominate the security industry. Securitas, a Swedish based firm, had revenues of $5.8 billion with a net income of $115.2 million in 2001.70 It employs 220,000 people worldwide, with 98,000 in the United States. Since 9/11, they have hired more than 10,000 additional guards to serve U.S. accounts. Similarly, the Danish firm Group 4 Securicor had revenues of $2.81 billion dollars, with a net income of $3.7 million dollars in 2001. This firm employs 400,000 full- and part-time personnel worldwide, with 53,000 in the U.S., of which about 3 to 5 percent are directly attributable to 9/11.71 By any account, these are impressive numbers, both in terms of revenue and employee growth. Overall, the data suggest that the private security is so disproportionately large compared to that of public policing, some observers argue that private security is now the primary protective resource in the nation.72 Based on expected additional terrorist incidents, these numbers will likely grow—possibly substantially.

Likewise, the ratio of public police officers to reported crimes has undergone a dramatic change. In the 1960s, there were about 3.3 public police officers for every violent crime reported. In 1993, there were 3.47 violent crimes reported for every public police officer.73 While crime levels have decreased since then, these statistics illustrate that each public police officer in contemporary America must deal with 11.45 times as many violent crimes as police from previous eras. Walinsky notes that if this country were to return to the 1960s ratio of police to violent crimes, about 5 million new public police officers would have to be hired by local governments.74 This has not occurred and will not occur. Instead, the security industry has stepped in to serve this growing market need.

Justice Department data reveal that despite the decreasing ratio of the number of police to that of violent crimes, the economic costs of public policing increased from $441 million in 1968 to about $10 billion in 1994. This represents a 2,100 percent increase in the cost of public policing, while the number of violent crimes exploded 560 percent from 1960 to 1992.75 Thus, as crime rates increased, the tax monies used to “combat” crime also dramatically increased. While more recent Justice Department data reveals that crime has decreased from 1994 to 2004, one obvious question begs to be answered: Would spending additional money on public policing, in fact, reduce crime? Based on this short historical and statistical overview, the answer appears to be no. The most obvious conclusion to be drawn from these statistics is this: Over the last generation, the relationship between the amount of crime and the amount of money spent on public policing has changed radically.

As dramatic as these statistics may seem, numerous authors assert that the security industry should not be assessed on data alone. Indeed, the sheer and undeniable growth of the industry can be viewed by its involvement in businesses, homes, and communities throughout the country.76 This involvement stems from such diverse services as alarm systems, security guard services, and investigative and consulting services. Indeed, the impact of the security industry may even be more substantial than what this data suggests. For example, one observer noted, “We are witnessing a fundamental shift in the area of public safety. It’s not a loss of confidence in the police, but a desire to have more police.”77 Indeed, there are appropriate comparisons being made of the security industry in relation to the advent of public policing in the mid-1850s. In light of the historical summary, this comparison of private security to the advent of public police seems right on the mark.

Numerous authors have argued that there is a need for more police, or at least more protective services.78 Other authors have a more critical view. They doubt the capability of the public police to provide an appropriate level of protection.79 In either case, private policing may be seen as the “wave of the future.”80 Similarly, another author observed, “People want protection, and what they cannot get from the police, they will get from private security companies.”81 This statement has particular significance in light of the current increased terrorist threat. The authors of the National Policy Summit suggest a connection between this threat and the conflicting roles facing modern police departments. In their analysis, police are finding that in addition to the crime-fighting duties, they now have significant homeland security duties.82

The impact of crime on average people suggested by a 2004 survey conducted by the Society of Human Resource Managers (SHRM) is worth considering. The researchers asked, “Do you feel safe at work?” The majority of respondents answered no. Indeed, for almost every demographic and industry category, safety at work ranked at the top or near the top in terms of employee priorities. Specifically, safety was the number one issue for women, and tied for first with benefits for older employees. Overall, “feeling safe at work” was ranked “very important” by 62 percent of the respondents, up from about 36 percent two years previously.83

Business leaders also need to assess the current threat environment and consider security countermeasures. A Booz-Allen Hamilton study conducted in 2002 surveyed seventy-two CEOs from firms with more than $1 billion in annual revenues. This study revealed their post-9/11 security concerns. This survey found that 80 percent of respondents believed that security is more important now than it was prior to 9/11, with 67 percent actually incurring or anticipating substantial new security costs.84 In addition, expenditures for security-related personnel and hardware were tracked and summarized in another study (see Table I-1).85 The data in this table reveal an increase in the use of various security methods as well as a reduction of security expenditures by some firms. This trend in the data seems to suggest that despite the threat posed by crime and terrorism, some organizations still remain content to believe that “it won’t happen here.”

Other more recent studies conducted after the London train bombings and Hurricane Katrina reveal that “there is an increased focus on domestic safety and security.”86 One study revealed that 56 percent of companies have revised their disaster preparedness plans, while 44 percent have not. Again, the statistics suggest that while some people will seek to prepare for or prevent a disaster, others prefer to merely to hope for the best.87 As previously asserted, this mind-set will always exist in some measure—despite the liability exposure and security threats facing society.

Considering the impact of liability exposure upon business, the incentive to provide security is substantial. In 2004, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce reported that small businesses incurred more $88 billion annually in litigation expenses.88 An employment law firm’s annual survey in 2003 reported that 57 percent of companies had an employee file a lawsuit against the company, up 8 percent from 2002.89 The EEOC itself collected more than $420 million dollars from employers who had violated discrimination laws. Of course, regardless of whether a lawsuit has any legal merit, litigation has both direct and indirect costs to the employer. These costs may include attorneys’ fees, lost productivity, decreased employee morale, increased turnover, and poor public relations. Clearly, it is important to provide a secure workplace environment, since crime prevention and misconduct reduction have wide-ranging implications.

NEGLIGENCE ELEMENTS AND PRINCIPLES

In order to assess the liability exposure related to crime and misconduct, one must consider the tort of negligence. Negligence can be defined as the failure or omission to do something that a reasonable and prudent person would do, or doing something a reasonable and prudent person would not do. Negligence causes of action have four elements: duty, breach of duty, causation, and damages. As was explained previously, government has no constitutionally defined duty to prevent crime. Crime has traditionally been considered a superseding cause that broke the causation connection in a negligence-based claim. This superseding cause in a negligence action is illustrated in Figure I-1.

Duty

Duty is the standard of care that a reasonable and prudent person is required to maintain. This standard is objective. Unfortunately, it is difficult to definitively determine an objective standard. It is based on what a reasonable and prudent person would do or not do.90 The logic is that the imposition of a duty often affects an individual’s behavior, since people tend to conform to the duty in order to avoid potential liability.91 In the context of crime, the imposition of a duty is designed to keep people safe from crime. This does not require preventing the crime from occurring. Sometimes crime cannot reasonably be prevented. In a perfect world, no crime would occur. Of course, this world is far from perfect. It is clear all crime cannot be prevented, even if the property and business owner tried to prevent it. Indeed, courts do not require perfection. What is typically required is the institution of reasonable security methods in order to diminish the probability that crime will occur. In achieving this standard, security methods can stem from a brighter light bulb to Fort Knox—and anywhere in between. How then does a reasonable and prudent person assess what security methods would be sufficient? The answer is the proverbial million dollar question. Indeed, in security litigation, it is often a multi-million dollar proposition.

Figure I-1 Crime as a superseding cause in negligence.

Fortunately, there are principles that can be used to assess the appropriate level of duty. Broadly speaking, duty can be defined by particularized relationships and by the concept foreseeability.92 Courts typically consider duty of care as being based on three broad factors: the circumstances, the terms of the contract (if any), and the expectations of the “special relationship” between the parties (if any). Before considering these factors, some additional explanation is necessary.

First, the notion of a special relationship imposes a duty on the business or property owner. Such relationships include that of common carriers, such as trains and buses, to their passengers. The relationship between hotels and their guests is another example. Implicit in these relationships is a circumstance in which the safety and security of the subordinate party (the passenger and the guest) are in the hands of the business owner and proprietor. In the logic of this relationship, the superior party (owner and proprietor) has an increased or enhanced duty to protect those who depend on that party for their safety and security. Since the existence of a special relationship is often posed in security litigation, these issues will be developed throughout this book.

The second aspect of duty relates to the terms and conditions of the contract, if one exists. This assessment is typically straightforward. Generally, what is articulated in the contract is what is required by the respective parties. In this way, the duty is based on the language of the contract, or the agreement of the parties. These issues will be more fully developed in Chapter 9.

The third aspect of duty is the most difficult to assess because it is based on the circumstances surrounding the incident. With this assessment, the operative facts often dictate whether a duty exists, or the extent of the duty imposed. In this thinking, a general principle is relevant to the assessment. As danger increases, the actor (owner or proprietor) is required to exercise caution commensurate with the risk. For example, if the risk of crime is particularly great, then the required security measures to prevent crime may increase. The appropriate relationship between the risk of danger and the commensurate duty, however, is tricky to definitively define. Indeed, doing so can be construed as both an art and a science. This is what makes the analysis contained in this book pertinent and relevant. Performing a reasonable and prudent analysis to determine the appropriate security precautions for addressing a particular level of risk requires an understanding of both legal principles and security methods.

The typical approach to such an analysis is based on foreseeability.93 The concept of foreseeability can include what the actor (owner or proprietor) actually knew, as well as what that actor reasonably should have known. Thus the actor may be required to anticipate the risk of harmful acts of third persons. This thinking mirrors the description of a landowner’s duty of care in the Restatement (Second) of Torts, which provides that reasonable care must be exercised to discover what harmful acts are being committed or are likely to be committed, give an adequate warning, or otherwise protect the visitors against the harmful acts.94 In this sense, foreseeability may be determined in terms of past experience and future probabilities. It is based on whether the likelihood of conduct by third parties will endanger the safety of those within the particular environment. This assessment takes into account a number of factors, including the following:

1. Crime rates and prior similar crimes 2. Lack of customary security measures (by business in area or by particular location)

3. Statutory violations (repair or maintain building)

4. Nature of the business

5. Area or neighborhood where the business is located

6. Standard of security methods in the particular industry

7. Hours of business operation for the business

8. Specific complaints about crime, misconduct or suspicious behavior at the location

9. Expert advise from police or security consultants 10. Relationship between owner’s conduct or action and the injury incurred

11. Extent of injury incurred by the victim (plaintiff) 12. Moral blame attached to the conduct or inaction of the business proprietor

13. Public policy considerations related to preventing harm, including the magnitude and consequence of burden of preventing such harm

14. Availability and cost of insurance for the risk involved

Obviously, these factors are detailed and fact specific. They are also complex to assess and difficult to predict. This list demonstrates the diverse factors that courts may use to assess foreseeability. However, it is important to distinguish factors from tests. Factors are facts or situational assessments. Tests are legal standards. Typically, tests will often focus on certain specific factors, as being more important to the particular test. For example, in a prior similar incidents test, the lack of any previous crime would defeat the claim. Conversely, in the totality of the circumstances test, the court would consider all factors, not just previous crimes. Consequently, the particular test used by the court is a, or even the, critical determination of liability.

There are various tests that courts use to determine foreseeability. Specific tests include: (1) the specific harm test, (2) the prior similar incidents test, (3) the totality of the circumstances test, (4) the balancing test, (5) the known aggressor/imminent danger test, (6) the actual or constructive knowledge test, (7) the special relationship/special circumstances test, and (8) blending of various tests. While these tests have some overlap, their basic characteristics can be described.

Under the specific harm test, a landowner owes no duty unless the owner knew or should have known that the specific harm was occurring or was about to occur. As this is a very restrictive standard, most courts are unwilling to hold that a criminal act is foreseeable only in these situations.

Under the prior similar incidents test, a landowner may owe a duty of reasonable care if evidence of prior similar incidents of crime on or near the landowner’s property shows that the crime in question was foreseeable.95 Although courts differ in the application of this rule, all agree that the important factors to consider are the number of prior incidents, their proximity in time and location to the present crime, and the similarity of the crimes.96 Courts differ in terms of how proximate and similar the prior crimes are required to be as compared to the current crime. Courts can apply more liberal or more conservative standards for this test. For example, in a gun assault case, one court held that although there were 57 crimes reported over a five-year period, only six involved a physical touching. In this conservative jurisdiction, the assault with a gun was deemed unforeseeable. Conversely, in a liberal jurisdiction, two prior burglaries of apartments were sufficient to make a rape in an apartment foreseeable. Notwithstanding this difference, this test typically depends on the location, nature, and extent of those previous criminal activities and their similarity, proximity or other relationship to the crime in question.

While this approach establishes a relatively clear line when landowner liability will attach, some courts have rejected this test for public policy reasons. The typical public policy criticism is that the first victim in all instances is not entitled to recover. As such, if there were no prior similar incidents, landowners have no incentive to implement even nominal security measures. Hence, some argue this test incorrectly focuses on the specific crime and not the general risk of foreseeable harm. Indeed, one can make the logical argument that the lack of prior similar incidents relieves a defendant of all liability. This is so, even when the criminal act was, in fact, foreseeable due to generalized crime within the community. However, advocates of this standard argue that merchants should be responsible only for the dangerous conditions they created. In this sense, prior similar incidents would act as “constructive notice,” which protects the interests of the customer, while giving the property or business owner a fair opportunity to take steps to shield them from liability.97

Under the totality of the circumstances test, a court considers all of the circumstances surrounding an event to determine whether a criminal act was foreseeable. This may include the nature, condition, and location of the property and the larger community, as well as prior similar incidents in and around the property in question.98 Courts that employ this test may do so out of dissatisfaction with the limitations of other tests, such as the prior similar incidents test. The thinking behind this test is that all relevant factors associated with the crime should be taken into account. The wide scope of this test is favored by those who seek to prevent crime—and by those who advocate liability for those who fail to prevent crime.

A frequently cited limitation of this test is that it tends to make fore-seeability too broad and unpredictable, effectively requiring that landowners anticipate crime. Indeed, the numerous factors cited above are difficult to assess and predict. Sharp argues that foreseeability alone does not create a duty. Rather, the ability to have foreseen and prevented the harm is the key determinative of responsibility inherent in this duty.99 Nonetheless, this test is very popular with courts as it gives a wide-ranging analysis to all relevant factors related to the incident. Hence, this test is useful because it can incorporate all relevant factors. However, it is difficult to apply for the same reason.

Under the balancing test, courts balance “the degree of foreseeability of harm against the burden of the duty to be imposed.”100 In other words, as the foreseeability and degree of potential harm increase, so does the duty to prevent it. However, the burden of preventing foreseeable crime must also be considered. For example, in high-crime areas, the burden of preventing crime may become too onerous as to drive away all commerce. Hence, this test seeks to balance the foreseeability of crime against the burden of preventing crime. In this assessment, the burden is considered in various ways, including the cost of security measures, the economic impact of a “hardened” business environment, and the feasibility of security measures to actually prevent crime. Because this is a difficult “balancing act,” this test still relies heavily on prior similar incidents in order to ensure that an undue burden is not placed on business or landowners.

Under the known aggressor/imminent danger test, courts assess whether the owner or proprietor had reason to know that a particular assailant is aggressive, belligerent, or prone to violence against customers or patrons. This is a very factually specific test, where knowledge of the particular offender’s actual violent propensities is critical to imposing liability. If this knowledge is not shown, then liability for the crime will not attach.

In a similar test, the actual or constructive knowledge test, the owner or proprietor must have knowledge, either actual or constructive, of the threat posed by an offender or of the crime that was likely to occur. As with known aggressor/imminent danger test, this is a very restrictive test. It requires a high level of knowledge and specificity of the offender or of the crime. One distinction between this test and the known aggressor/ imminent danger test, is that actual or constructive knowledge test provides for a longer temporal assessment. In order for liability to attach, the former focuses more on the time frame between the knowledge and the crime. The latter allows for liability with less emphasis on time considerations, with more emphasis on what the business or property owner knew—or should have known—about the potential for crime to occur. While this is not a definitive distinction between the two tests, it is a way to frame the logic of both.

As mentioned earlier, the special relationship/special circumstances test focuses on the relationship of the parties, such as hotel-guest, carrier-passenger, and the like. This test, however, also looks at the circumstances surrounding this relationship. In this way, the status of the parties (special relationship) is coupled with relevant factors (special circumstances) in the assessment of liability.

As shown by the short descriptions of these different tests, there is substantial variance in how liability assessments are made. The fact that different states use different tests further complicates the task of assessment. Consequently, the following table was developed as a reference to facilitate the process.101 Before using this table, a few caveats are in order.

First, the table lists tests applied in each state. While this information appears straightforward, the fact that some states have developed standards that are difficult to characterize in any definitive manner creates some ambiguity. For example, some states will use a defined test, such as prior similar incidents, but will differ in its application. In this way, a particular state may use a more liberal view versus others that may use a more conservative approach. Hence, even when the test is defined, the application of the test may vary based on a liberal or conservative bend or mind-set of the court.

Second, the chart lists tests that are sometimes adaptations from several different tests that are often also difficult to characterize in any defined way. For example, when one compares the actual or constructive test to the aggressor/imminent danger test, the distinctions are fine or slight. In the former, the test seems to combine knowledge of the offender and of a particular crime, while the latter focuses much more directly toward the particular offender who may commit a particular violent crime. This assessment also takes into account the temporal factor discussed previously. In fact, the distinctions between these tests may be so fine as to be legally and factually meaningless. Notwithstanding this assertion, the test articulated by the court is the one listed in the chart.

A third issue related to this caveat is that sometimes a particular state will not articulate a particular test or it will change from one test to another. Since legal standards are very fact specific, courts may tend to frame the legal analysis around the facts of a particular case. Hence, sometimes there is a “chicken and an egg” scenario. Stated another way, it is difficult to assess which is paramount, the legal standard or the facts. The interrelationship between the two sometimes makes it hard to distinguish which has first priority.

Given these complicating factors, the reader should review Table I-2 with some caution. Despite these caveats, this table nevertheless remains a valuable tool. Indeed, the value of this table is that it attempts to define a difficult, often fluid, area of the law. To the best of my knowledge, no other author has developed a table of this type. Hopefully, the attempt to place clear distinctions between the varying state laws into an easily reviewable table can be a useful tool for those who need to get a sense of the law in a particular state, or of the broader concept of security law. While it may appear that the caveats mentioned above “swallow” the table, the reality is that the chart reflects the difficulty in assessing security law generally. That is, security standards, just like legal standards, are very fact specific. Sometimes facts are difficult to neatly categorize. As a result, security and legal standards are also hard to categorize. This is one of the reasons why books such as this one are useful and necessary. Stated another way, the value of the table (and this book) are that they shed light on difficult and fluid subject matter.

The table includes three general categories: the state, the legal test, and the legal authority. When using the table for litigation or security purposes, please check the case authority and research the law of the state to assess its current legal standard.

Breach of Duty

Breach of duty is characterized by a failure to act or by conduct that falls short of the applicable standard of care. In essence, the actor failed to do what a reasonable and prudent person would do in the circumstance. Alternatively, the actor did something that a reasonable and prudent person would not do in the circumstance.

For example, consider the hypothetical case of a security officer assigned to guard a movie theater. If a fire started in the theater, the security officer would be required to take some affirmative act, such as calling 911, notifying supervisory personnel, or escorting patrons from the facility. If the security officer failed to carry out any such act, this omission would likely be deemed a breach of duty by a court. Alternatively, if the security officer yelled “fire” in the crowded theater and then ran out of the facility, this conduct would also likely be deemed a breach of duty by a court. In either case, there is an affirmative duty to act in a reasonable and prudent manner under the circumstances. The failure to do so may result in the breach of the duty of care.

Generally, in the context of security personnel, the standard of care is based on how a reasonable officer confronted with a similar situation would act. Absent some affirmative misconduct by a security officer, the failure to prevent a criminal act is usually not considered a breach of duty. The key issue is whether the security officer promptly reported the incident, and took other appropriate measures to secure people and property in and around the crime scene. In the context of property or landowners, the standard of care is the duty described in the discussion and in Table I-2. If this duty is not adhered to, it is deemed breached.

Causation

The legal term for causation is proximate cause. This element imposes rational limits on liability based on some cogent connection between the conduct and the harm suffered. Generally, the closer the connection between the conduct and the harm (damage), the most likely the conduct will be deemed the proximate cause of the harm. This connection is assessed in terms of time, space or distance, sequence of events, and the like. A typical assessment of causation is through the substantial factor test. In this test, the question is whether the defendant’s conduct (or omission) was a substantial factor of the incident causing (or contributing) the injury or the harm. For example, if a crime would have occurred despite any reasonable security precautions, then the causation element was not satisfied.102 The question of causation in security cases typically involves two key issues:

1. Whether certain security measures would have likely dissuaded the offender from committing the crime

2. Even if the offender would not have been deterred, whether certain security measures would have enabled security or police officers to interdict the offender

Damages

The damage element stems from the breach and is connected by causation to the harm or injury. In the elements of negligence, the harm or the injury is called damage(s). There are many types of damages and many ways to calculate damages. Types of damage claims include:

1. Compensatory (general) damages entail the non-tangible impact, including:

a. Mental anguish

b. Emotional distress

c. Pain and suffering

d. Loss of enjoyment

2. Special (economic) damages entail the tangible impact, including:

a. Medical expenses

b. Lost earnings

c. Lost earning capacity (future earnings)

d. Rehabilitative expenses

e. Future medical expenses

3. Exemplary (additional) damages entail supplementary penalties, including:

a. Punitive (for punishment and deterrence)

b. Treble (three times)

4. Wrongful death relates to the damages created by the death of the person

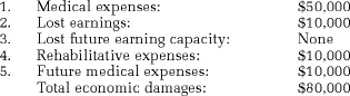

While there is no set calculation of damages, my experience is that the following formula is typical in a negligent tort claim. Typically the economic damage amount can be calculated to a rather precise figure. Remember this aspect of damages is the most tangible. This figure will be the total of each subsection of this category. For example, consider these damage amounts:

Using this figure as a baseline, the formula requires this amount be multiplied to represent the general (non-economic) damages. This calculation is as follows:

$80,000 (economic damages) × 3 or 5 or 7 (general damages) = Total demand or total value of claim.

Here the intangible aspect is the appropriate multiple to be used in this equation. If the multiple is three (3), then the equation is: $80,000 × 3 = $240,000. If the multiple is five (5), then the equation is: $80,000 × 5 = $400,000. If the multiple is seven (7), then the equation is: $80,000 × 7 = $560,000. The numbers would change depending upon the multiple used in the formula. In this way, the higher the multiple, the higher the recovery. In my experience, it is unusual to obtain a multiple in double digits. While this does occur, it is not very frequent. The key to the amount of the multiple depends on a number of factors, including the negotiation or litigation skills of the attorneys, the sympathy generated by the plaintiff (or lack thereof), the ease of demonstrating liability (or stated in the opposite way—the difficulty in proving liability), the forum where the case was filed, the existence and amount of insurance coverage, and the other factors which are relevant to the particular case.

Finally, if punitive or treble damages are relevant, these would be applied as a separate category. For example, treble damages are three times the total damages. Treble damages are damage provisions derived from specific statutes. They are designed as incentives to increase the likelihood that the statute would not be violated. In essence, treble damage clauses triple the value of the claim. This can be a real motivation in potential litigation.

Punitive damages are designed to punish the bad conduct of the defendant, and act as an example to deter others from similar bad conduct. Two key U.S. Supreme Court cases govern the standard of punitive damages.103 These cases provide that punitive damages should be framed within three “guideposts.” These are the degree of reprehensibility, the ratio between compensatory and punitive damages, and of awards in similar cases. These guideposts were summarized by Stamatis and Muhtaris.104 As to the degree of reprehensibility, it is generally considered the most important indicator. This indicator has great significance in security law claims, as it looks at the defendant’s conduct in light of the following:105

1. Whether the defendant caused physical as opposed to only economic pain

2. Whether the defendant showed indifference to or reckless disregard for health or safety of others

3. Whether the defendant was involved in repeated acts or omissions

4. Whether the injury or harm was caused by an intentional act, not simply an accident

As to the other two indicators, the ratio between compensatory and punitive damages is deemed the least important factor.106 Indeed, the case of State Farm Auto Insurance Co. v. Campbell, 538 U.S. 408 (2003) stands for the proposition that there is no “bright line” mandate between these types of damages. In this way, the court held that there is no one standard, no “one size fits all formula.” Consequently, the range of damages that could be applied is based on the facts and circumstances of the case.

Whatever the “correct” amount is deemed to be, the key in this regard is to understand the formula used to assess the “value” of these cases. Of course, value does not just equate with money. The damage done to crime victims often is not corrected by money. What is the value of losing a loved one? Can a woman who was brutally raped be adequately compensated? What about the victim of an armed robbery who has to return to work—the scene of the crime—to continue to serve his clients? Can these people be “fixed” by money? Many, if not most, would answer no. Unfortunately, the legal system can do little more for these victims other than to award money damages. Money is intended to make the victim whole. As inadequate as this may be, this is the best that the system can achieve. Of course, the better answer is to prevent the crime from occurring. Hopefully this book will help serve to achieve this goal, even in some small measure.

When considering how to limit crimes by third parties, or at least limit the liability exposure from such, there are three basic approaches: pre-incident assessments, post-incident investigations, and legal defenses and theories. Each approach is distinct. Each approach, however, is interrelated to the others. For example, if there was no pre-incident assessment, then this will affect the post-incident investigation, which in turn relates to the legal defenses and theories tied to the case. Each of these approaches will be presented independently, but keep in mind that they are interrelated. This will become more obvious when the legal defenses and theories are presented.

PRE-INCIDENT ASSESSMENTS