CHAPTER 10

Rethinking Anger

Anger. Some of us fear it. Some of us thrive on it. Understanding it better can help us to manage it.

Stretching across the Chesapeake Bay just east of Annapolis is the broad expanse of a bridge. If you are riding across that bridge on a clear Sunday afternoon in the spring, you can catch glimpses of a hundred sailboats. Some are headed up the bay, some down. Others are aiming for shore, on either the southern bank or the northern. All of them are using the same wind. Sailors know they need the wind to keep them moving. Too little wind and the boat sits becalmed in the water; too much wind and the boat is in danger of capsizing. But a good, steady breeze? The sailor knows how to set the sails, capture the energy, and move the boat in any direction he or she wants to go.

Think of your emotions as that same vital force. Your thoughts, your reasoning power, function as the rudder, giving direction to that emotional energy. Though you may often be unaware of your emotions, they are generating energy that affects the cognitive, thinking parts of your brain.

Here is an experiment to try with friends or family, or yourself. Ask them, “How do you feel about … [insert your own topic or idea]?” Notice the words that each person uses to describe his or her “feelings.” How often is the answer, “I think …” or “I believe …”? The phrase that follows “I think” or “I believe” is not a feeling—it is a thought. If the answer is, “I feel that …” then what follows the word that is also a thought, not a feeling. But the answer that begins with “I feel” or “I am” and uses words like happy or sad or scared or upset is describing feelings.

Emotions—feelings—are partly mental, partly physical responses marked by pleasure, pain, attraction, or repulsion. They are not the enemy to be overcome; rather, they are an important source of information, energy, and guidance when we are aware of them. For many of us, most of the time our emotions are unconscious. Learning to be aware of our feelings, to put appropriate words to our emotions, is a skill to be learned and practiced on a daily basis. You may not know what your feelings are, yet they may be driving your thoughts and your actions without your even realizing what is happening.

It is easy to see how positive feelings move us. The sun is out this morning, the sky is blue, and a cool breeze whispers through new spring leaves. I wake up happy, excited to move into the day and find out what it might hold. The wind is in my sails, and it is a very good thing! It is sometimes harder to see how negative emotions like fear, sadness, envy, frustration, and anxiety can also give us energy to get things done. When the deadline is approaching, a little bit of fear-generated adrenaline gives us the energy to take action, to put aside the distractions and get to work. A healthy dose of fear can keep us from taking risks that are dangerous. Frustration can be an energizer, as well as an immobilizer.

In conflict, those negative emotions come to the fore. When what you want, need, and expect is getting in the way of what I want, need, and expect, emotional energy stirs inside both of us. How we manage that energy determines the direction in which the conflict will go. Often, when I am dealing with a workplace conflict, someone explains to me, “We don’t have emotions here; this is the office. That stuff is for home.” Or maybe, “If we could just keep the emotions out, we could resolve this and get back to work.” But is this truly the case?

We must shift our thinking about emotions. They are a part of our reality at every moment, in every place, and it is dangerous to ignore that reality. Not only are emotions intimately tied to our thoughts and create the energy for our responses, but like those boats out on the bay, we need that energy to move us through conflict productively.

The Physiology of Emotions

Here’s a disclaimer: I am not a neuroscientist. However, I do know that our knowledge about how the brain functions is expanding at a phenomenal rate. Daniel Goleman brought public attention to the world of emotional intelligence in his book of the same name.1 In an early chapter, he begins to explain the physiology of our emotional reactions, which gave me my first introduction to many of these concepts.

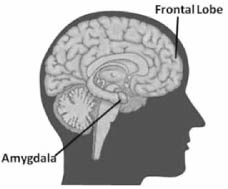

Here is my brief summary of how your brain works: Just behind your forehead are the prefrontal lobes, that part of the brain we are so proud of. This is where we “think”—problem-solve, plan, build positive relationships. Surrounding the top of the brain stem are several centers that generate emotional responses. Sometimes people call this the “lizard brain.” It functions powerfully and often unconsciously (see Figure 10-1).

Back between your ears, near the top and on either side of the brainstem, there is an almond-sized area of the brain called the amygdala. This emotional response center has stored memories of our emotional life history and is primed to kick the body into action when it senses a similar moment coming around again. Small as it is, the amygdala is a powerful response center that controls our fight or flight reactions. It triggers the release of powerful drugs into our systems—adrenaline and norepinephrine. And it responds some 1,000 times faster than the frontal lobes.

One way you might understand how this happens is to remember what happens when you watch a scary movie. You sit safely in the theater, intent on the screen. Nothing much is happening at the moment. The camera slowly pans from room to room. Your palms are sweaty, your heart is pounding, you can hardly breathe. Your amygdala has triggered an alert: “Something is about to happen,” and you are primed for action. You have not consciously thought (in the frontal lobes), “Oh, listen, the music is increasing in intensity, I think something is about to happen.” Maybe you remember the scene in Alfred Hitchock’s Psycho, when the woman is showering, or the ominous theme from Jaws. Your amygdala, without any conscious thought, has picked up the cues from the music and has triggered the release of adrenaline and norepinephrine, which are now coursing through your system. You are fired up, ready to go!

Most of the time, there is a healthy flow of information between these two centers—the frontal lobes and the amygdala. The frontal lobes work in synch, helping to calm the amygdala by taking appropriate action as needed. The amygdala gives the frontal lobes energy and information about what is important to us and how much it might matter. That balance is right where we want our brains to be.

Much research has been done on people whose amygdalas no longer function: they are not able to identify fear in themselves or in others. This inability can cripple a person’s ability to take action when he or she needs to, to hold onto relationships that the individual cares about, and to be able to connect with other people. People need the response mechanism of the amygdala to generate energy for the cognitive areas of the brain to be able to make decisions. In other words, with no amygdala, we are those boats on the Chesapeake Bay, stranded in the middle of the water, desperately in need of a little wind.

Emotional Hijacking

Picture one of those boats on the bay when a sudden summer storm blows up. The wind takes the sails broadside, and before we know it the boat is heeling hard over, with water washing over the gunwales. The hand at the tiller struggles to maintain control of the boat. Most of us have been there emotionally at one time or another. Sparking from zero to sixty in seconds flat, suddenly we are in the middle of a heated argument, popping back hot responses. Maybe we slam the door on our way out. We no longer have access to the frontal lobes—to the thinking, reasoning part of our brains. The phrase that is often used to describe this is so accurate: emotional hijacking. The thinking part of the brain has been taken over by the emotions. Some people spend a lot of time in this zone; others rarely venture there.

Briefly, here is what happens. When the amygdala triggers an emotional response, it sends a strong dose of those chemicals through the system. The cortex (in the thinking part of the brain, the frontal lobes) gets reduced to making up justifications, or rationalizations for the emotions that have just erupted. The cortex’s ability to think clearly, to create, to explore, is reduced or eliminated. When I have been emotionally hijacked, asking me to “calm down” or to think rationally is an exercise in futility—that attempt may make me even more irate. I no longer have access to the frontal lobes.

Rational thought stops. Gone is the ability to problem-solve or think creatively. Here is what I have instead:

![]() Flawed judgment

Flawed judgment

![]() Confused perceptions (seeing or hearing things inaccurately)

Confused perceptions (seeing or hearing things inaccurately)

![]() Impaired ability to learn or remember

Impaired ability to learn or remember

![]() Reduced ability to say what is true and accurate

Reduced ability to say what is true and accurate

![]() Deadened creativity (except for finding creative reasons to stay angry)

Deadened creativity (except for finding creative reasons to stay angry)

![]() Misreading of social cues (assuming that others are hostile or angry)

Misreading of social cues (assuming that others are hostile or angry)

![]() Defensiveness

Defensiveness

![]() Polarized thinking (people take more extreme positions than they really believe, and hold onto them tightly)

Polarized thinking (people take more extreme positions than they really believe, and hold onto them tightly)

![]() Increased energy for blame (whatever has happened it is your fault, or somebody else’s; I have no responsibility for the situation)

Increased energy for blame (whatever has happened it is your fault, or somebody else’s; I have no responsibility for the situation)

Before people in conflict can productively work to resolve differences, they must recover from the negative effects of emotional hijacking. If the amygdala is not retriggered, in most people these chemicals will usually dissipate in the brain in about twenty minutes. For some people, however, the effects last much longer—hours or even days.

![]() Before you read any further, think of specific examples when you or someone you know has lost their temper, either staying to fight or storming out in flight mode.

Before you read any further, think of specific examples when you or someone you know has lost their temper, either staying to fight or storming out in flight mode.

Anger as a Secondary Response

Anger is not automatic. It is a secondary response to other feelings. Think of anger as the lid on a jar. To manage anger—yours or someone else’s—begin by understanding what is inside the jar, what’s underneath that lid.

Confused about my own anger, dealing with my teenage children’s anger, working with people who were frequently angry, I volunteered as a facilitator with my county’s spouse abusers program to understand more about anger: what triggers it, and how to manage it more effectively.2 Each week for eighteen weeks, a group, mostly men, filed into the room. Early in the program, we worked with the participants to connect their anger with their beliefs about themselves—often patterns that had been laid down early in life.

One brave man volunteered to participate in front of the class. The group leader asked him to close his eyes, clear his mind, and remember a moment when he was really upset. The man then told a story, as if it had happened yesterday, of a lamp that was broken in his home when he was a teenager. In a rage, his father blamed him for it, hit him, and sent him to his room.

Our group leader asked, “How did you feel?” He, in tears, responded, “I felt blamed for something I didn’t do. I didn’t do it. I wasn’t even there when it happened.” After identifying these feelings, the leader led him though the process of unhooking that experience from the truth about himself. That feeling of unworthiness had followed him for all those years.

My eyes as well as the students’ were opened. By the end of the class they were saying, “We should have learned this in high school.” So much of what they learned—what I was teaching, and what, ultimately, I learned—opened my eyes and my heart to what was happening between me and my children. This translated well to the situations I deal with in the workplaces I enter.

In Chapter 13, I tell a story from my own experience to describe a solution-seeking process. But here is the beginning of that story, as another example of understanding the feelings that undergird anger.

Anger starts with an Ativating event. Somebody says something or does something. Maybe it’s nonverbal and barely visible—when you speak, he rolls his eyes, or maybe you make a statement and someone shrugs her shoulders. In that moment, the amygdala picks up the verbal or nonverbal cue and triggers an emotional response. Nearby, the hippocampus, the storage center for previous fearful situations, works closely with the amygdala, calming or intensifying the amygdala’s responses. The amygdala translates these impulses into Beliefs: I am being attacked, or I am being accused, or I am being disrespected. When the amygdala sends those chemicals into the rest of your system, and you react—fight, flight, or freeze, depending on your own disposition, or maybe depending on your mood that day—you are experiencing the emotional Consequence. These are the ABCs of anger.

What are the beliefs that cause anger?

![]() I have been accused—falsely or not.

I have been accused—falsely or not.

![]() I have a reason to feel frightened.

I have a reason to feel frightened.

![]() I have been treated unfairly or cheated.

I have been treated unfairly or cheated.

![]() I am not valued.

I am not valued.

![]() I am powerless or I have no control.

I am powerless or I have no control.

![]() I have been disrespected.

I have been disrespected.

![]() I am unlovable.

I am unlovable.

Consider This

![]() Think about the situations you identified at the beginning of this chapter. What are the beliefs that caused the anger you experienced?

Think about the situations you identified at the beginning of this chapter. What are the beliefs that caused the anger you experienced?

![]() If the situation you identified was someone else’s anger, what might have caused the person to react the way he or she did?

If the situation you identified was someone else’s anger, what might have caused the person to react the way he or she did?

People Use Anger

People use anger to control, to win, to get even, to protect themselves. You probably know people who yell to get their way. Others respond by jumping into action, saying, “Just don’t yell at me.” And we all know someone who uses tears the same way. Those around the teary person are quick to respond, “Whatever you want, just don’t cry!” How do you handle these situations?

The amygdala is fully formed sometime between the ages of two and five. The frontal lobes that govern rational thought and decision-making skills are not fully developed until our mid-twenties, however, so it isn’t always easy going, especially when dealing with children. Remember the energy it took to control the sailboat in a heavy wind? All our lives, we practice how to respond to the amygdala’s emotional energy. By the time an adult is functioning in the workplace, the patterns of response are deeply set in his or her brain. Addressing those patterns as adults requires attention and energy over a significant period of time. To begin, just consider the challenge of dealing with children’s emotional responses.

Addicted to Anger

That child wanting the candy bar in the grocery store learns his lessons very well. He grows up and gets a job. His pattern of behavior—yelling or crying or stomping out of the room—honed over twenty years, is deeply etched into the brain’s neural pathways. Changing these patterns, creating new synapses and paths in the brain, is not an easy thing to do. Whether you are the person with a negative pattern you want to change, or you are working with someone with such negative habits, know that change will be slow in coming.

For example, my granddaughter has learned to put on her own pants by now. And like the rest of us, she has developed her own pattern for getting dressed. She holds up the pants and pushes her right foot through the pant leg first. Then, the left. Some of us do it the other way around, but we all develop a pattern that is comfortable, day in and day out. After the pattern is set, we don’t stop to think about it, about which leg goes in first. If we wanted to change that habit, though, first we have to be aware of it. Then, we have to consciously think each morning as we are getting dressed, “Oh, yes, I am going to switch to the other leg.” We have to do that over and over and over again, until we create a new pattern, a new habit.

How much harder it is to change our anger patterns and habits! This is true particularly if they seem to be working for us a lot of the time. Particularly if we are not even aware of them.

![]() When do you experience anger in your own work life?

When do you experience anger in your own work life?

![]() What feelings are behind the anger that you feel?

What feelings are behind the anger that you feel?

![]() What effect does your expression of anger have on others?

What effect does your expression of anger have on others?

![]() Are there patterns of behavior you would like to change?

Are there patterns of behavior you would like to change?

![]() Think of a situation when an employee was angry. What did he or she do to express that anger?

Think of a situation when an employee was angry. What did he or she do to express that anger?

![]() What might have been the feelings behind the anger that you witnessed?

What might have been the feelings behind the anger that you witnessed?

The natural, powerful chemicals I mentioned earlier—adrenaline and norepeniphrine—are serious drugs. Norepinephrine is used medically as an injection to get the heart going again if it has stopped. Realizing how powerful these drugs are helps us understand that sometimes people can be addicted to their anger. For them, it may be difficult to get moving in any direction without the shot of adrenaline or norepinephrine that the amygdala produces.

There is some good news on this topic, however. Several years ago, a conference brought together Buddhist scholars with Western psychologists, neuroscientists, and philosophers.3 The neuroscientists confirmed what Tibetan monks have experienced in practice for millennia. They reported that their research demonstrated a change in areas of the brain: through a consistent practice of meditation, an area of the frontal lobes behind the right side of your forehead enlarges. That area controls and mitigates the reactions of the amygdala. Over time, with this discipline, people are better able to manage fear, anxiety, rage, and anger. When neuroscientists reported this remarkable discovery, the Dalai Lama nodded (I paraphrase here), “Yes, of course. We have known this for thousands of years.” Obviously, Tibetan monks have learned a lot about how to control their own anger. How can we manage ours?

How to Manage Your Own Anger

Any anger arousal produces physiological changes. Usually these occur before we are consciously aware of our anger. So the wise manager practices becoming aware of the changes as early as possible so he or she can understand personal emotions and begin to regulate them.

Where do you first begin to notice your responses when you are getting angry?

When you feel yourself getting angry, wherever it might start for you, here are steps you can take to manage your response.

Breathe Deeply

When you feel the first flush of anger rising, take a deep, slow breath or, better yet, take several breaths. Oxygen to the brain helps to counteract the chemical rush of adrenaline and other drugs. This practice alone can shift your response, and can give you time and space and the ability to think. A daily practice of quieting your mind through focusing on your breath, even briefly, can help you manage those moments when you begin to feel angry. The practice itself is helpful in bringing equanimity to your system generally. Then, in those moments when you do experience that rush of emotion, the daily practice helps you to remember to breathe.

Take a Break

If you need to, take a break. There are a number of ways to do this. Excuse yourself for a few minutes. Suggest coming back to the discussion tomorrow or after lunch. If you can’t do that, at least inhale, count to ten, and mentally slow yourself down. Some jobs do not permit this option. If you are in one of those occupations, more practice is required to be able to respond effectively in the moment.

Take Stock of the Situation

Understand what is going on. Spend some time identifying the feelings that are behind the anger. Ask yourself, What is going on here? Why does this bother me so much? What am I afraid of? What specifically am I feeling? What need do I have that is not being met? What principles of mine have been violated? Try to put into words what is going on inside you: I feel hurt, or scared, or anxious … about. … Sometimes you can say it out loud, depending on who else is involved. Other times, just thinking it through or writing about it can help.

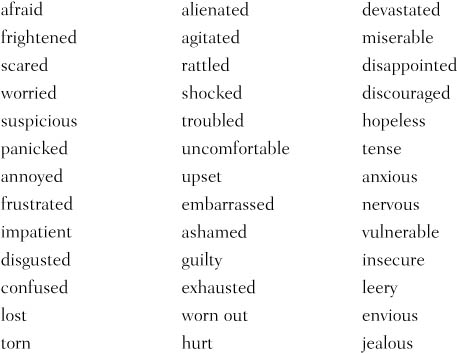

The process of putting your feelings into words moves some of the energy from the amygdala to more rational thought. Here are a few “feeling” words that may be useful:

After you’ve identified the feeling, think about the underlying beliefs or needs that are creating those feelings.4

How often is your anger not really about this person or this incident? Sometimes an event happening elsewhere in your life ramps up your emotions overall. Consider this scenario.

Create a Safe Place

Find a neutral space to hold that difficult conversation (for more on this, see Chapter 13). Find a private spot to talk and a mutually agreeable time, when neither of you is rushed or distracted. It can help to talk through the issues with a trusted, uninvolved friend. Sometimes you will get more clarity about what is going on and how you can respond by writing your thoughts in a journal. Or you can write a letter, put it in a drawer for a few days, then reread it before deciding whether to act on it.

Find a Physical Outlet for Your Anger

Try exercise. Take a walk. Go for a run. Dance. Practice yoga. Dive into the pool and swim a few laps. Go fishing. Build a deck or drive a golf ball. Become physically involved in some form of recreation that will get your mind off the situation. Warning: Pounding an imaginary foe does NOT reduce intense emotions. You are simply practicing being angry.

Avoid Personal Attacks

When raising an issue, focus on the problem, not on personalities. Take the No-Name-Calling Pledge: “I will not call other people names, no matter how angry I am.” Repeat the pledge as often as you need to. While you are at it, avoid the “You don’t ever …” or “You always …” argument, too. Name calling and personal attacks only create bigger messes that will require even more time later trying to clean up. The old saying, “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is not true. Words count: they sting and can ring painfully in someone’s ears long after physical wounds have healed.

Deal with the Current Issue

Throw away the baggage. Put grudges, resentments, and old hurts away. This resolution has to start with an understanding of what you are angry about. If you are not clear in your own mind about what triggered your anger, the other stuff—the old stuff—piles on pretty quickly, before you realize what has happened.

Keep Talking

If you take a break, be sure to come back and address the topic after the emotions have cooled. Continue, even when the relationship is strained, to talk to the other person, to say good morning or hello, in a civil way.

How to Respond to Someone Else’s Anger

Suddenly, someone is in your face, blaming you for whatever… . How do you keep your cool? Often, your first reaction is to fight back—or to leave the scene. But you can turn a potential argument into a discussion if you can hold on to your own sense of calm and stay determined not to be sucked into the other person’s negative energy.

When tempers flare, the better approach is for the boss to reprimand the employee for his actions—the language he has used as an employee. Instead, in this showdown, we can speculate that the employee walked away feeling he had won that round. What had he won? What had the boss accomplished? Remember: You can’t change another person, you can only change yourself. By shifting how you respond to others when they are angry or upset, you can begin to shift the dynamics and patterns between you and others.

Here are some tips for handling the anger of others:

Understand Your Own Responses

Know and understand your own responses to anger, your defensiveness, your hot buttons. This is the first step in developing empathy for others. It also helps you to be aware of, and less likely to be caught by, your own triggers.

Listen

Give others the opportunity to be heard—this is a profound and powerful experience. Allow the other person to let off steam, to explain his/her perspective, to vent. This can be really hard—to listen to someone who is angry at you. But when you can do it, the results are stunning. One way to practice is to mentally remove yourself from the immediate picture. Imagine you are looking and listening through a picture window, watching a story unfold, observing a scene without judgments or opinions. The other person might be surprised that you actually want to hear what he or she has to say. You might be surprised at what the person has to tell you. Remember: What they are saying is not about you. It is about the other person—what he or she thinks, how he or she sees things. You can decide later what you might want to do about what you have heard, whether you agree with it or not.

Check It Out

“It sounds like you might be feeling frustrated, or upset, or anxious … or…? I want to know more about it.” Ask it as a question, and be willing to listen to the answer. Making a flat statement such as, “So, you feel frustrated…” cuts off discussion rather than allowing it to proceed. Simply saying, “I understand” really doesn’t say anything at all. On the other hand, when you can put a “feeling” word onto what you are hearing and confirm it with the speaker—“Is that it?”—the two of you can connect on a deeper level. If you are making a sincere effort to listen, the other person is likely to think, “She really is listening to me and trying to understand.” Additionally, accept the person’s right to be angry. Acknowledging difficult feelings does not mean that you agree with them. (There’s more on this in Chapter 14.)

Take a Break

Interrupt the pattern and allow tempers to cool, without judgments or negative comments. Sometimes a short break (15 to 20 minutes) is sufficient. Other times a longer one may be needed. Perhaps you can come back after lunch, or the next day. Just be sure to come back to the topic and resolve it in a calmer moment. If someone loses his or her temper and that ends the discussion for good, then that anger has effectively controlled the outcome.

Create a Safe Place to Talk It Through

Take time to regroup, to think through your reactions and your response. Provide privacy and a neutral space within which you can work it through. Allow enough time for both sides to be heard and some resolution found. (More on this in Chapter 13.)

Consider the Source

Don’t take it personally. The other person may be angry about something or someone else. There may be other issues going on with co-workers or outside of work. Keep the conversation focused on the issue at hand.

Set Boundaries

Establish ground rules or guidelines for discussion, either before a difficult conversation or along the way as needed. Propose ground rules with shared responsibility and without judgments: “I cannot hear you when you are yelling. Can we agree to use respectful language?”

When a difficult conversation comes up, when you feel your own emotions swinging into anger, or you sense that the other person might be ready to blow, remember the boats on the Chesapeake Bay. Keep a steady hand on the tiller, guide the rudder in a positive direction, and don’t let a gale of anger capsize the boat.

Anger and Violence in the Workplace

News accounts of violence in the workplace amplify our fears about anger. We know that wherever people interact with one another there is the opportunity for anger to turn to violence. According to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, only 7 percent of violence that occurs in the workplace is caused by disgruntled employees.5 Still, any employee violence in the workplace is unacceptable.

What is a manager to do? Observing and reporting changes in people’s behavior are the best defense against this possibility. Know the policies and procedures within your own organization for handling potentially violent employees. The better you know your employees and coworkers, the easier it is to notice the warning signs. Here is a list of behaviors that indicate larger problems of anger and violence.6

1. Verbal threats. The person makes direct, veiled, or conditional threats of harm.

2. Constant negativity. The person is never happy with what is going on. He or she is consistently unreasonable and overreacts to feedback or criticism. The individual blows everything out of proportion and is unable to accept criticism of job performance; rather, he or she takes comments personally and turns them into a grudge.

3. Intimidation. The person uses intimidation of others to get his or her way (can be physical or verbal intimidation)—for example, fear tactics, threats, harassing behaviors including phone calls, stalking, and the like.

4. Paranoia. The employee thinks other employees are out to get him or her. The individual feels persecuted or the victim of injustice.

5. Not accepting responsibility. The person does not accept responsibility for own actions, makes excuses, blames others, the company, the system, for problems, errors, and disruptive behaviors.

6. Angry, argumentative, and confrontational. The person is frequently involved in confrontations and arguments with others, including supervisors, co-workers, and neighbors. He or she has low impulse control, slams doors, pounds fist, or is verbally aggressive.

7. Fascination with violence. The person applauds certain violent acts portrayed in the media, such as racial incidences, domestic violence, shooting sprees, or executions. He or she is fascinated by the killing power of weapons and their destructive effect on people, coupled with an excessive interest in guns, particularly semi-automatic or automatic weapons.

8. Vindictive. The person makes statements like, “He will get his” or “One of these days I’ll have my say.” The individual openly hopes for something bad to happen to the person against whom he or she has a grudge.

9. Desperation. The person expresses extreme desperation over recent family, financial, or personal problems.

10. Substance abuse. The person shows signs of alcohol and/or drug abuse.

If you are concerned about an individual’s behavior, if you notice these tendencies, talk with someone in the human resources office, an Employee Assistance Program (EAP), or a mental health professional to determine what steps to take. While the occurrence of workplace violence is rare, sometimes we read about tragedies in the newspaper in which others had noticed negative behavior earlier but had failed to take any action until it was too late.

Notes

1. Daniel Goleman, Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ (New York: Bantam Books, 1995).

2. Steven Stosny, Treating Attachment Abuse: A Compassionate Approach (New York: Springer, 1995).

3. Daniel Goleman, Destructive Emotions: How Can We Overcome Them? (New York: Bantam Books, 2003).

4. Marshall B. Rosenberg, Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life (Encinitas, Calif.: PuddleDancer Press, 2003).

5. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006, http://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2006-144/#a11; accessed November 15, 2010.

6. Adapted from “The Unlucky 13: Early Warning Signs of Potential Violence at Work,” National Institute for the Prevention of Workplace Violence, http://www.ncdsv.org/images/The%20Unlucky%2013_Early%20Warning%20Signs %20of%20Potential%20Violence%20a%E2%80%A6.pdf; accessed November 15, 2010.