RULE # 4

Interviews: They’re About the Value You Demonstrate

THE NEXT STEP in getting your job requires that you ace those interviews. Being invited for an interview is good news because it means you have moved to a higher rung on the Job-Search Pyramid, which was shown in Figure 3.1. You have piqued the interest of the hiring organization, and it is willing to explore your credentials further. Congratulations! In this era of supercompetition among white-collar workers, you have put your best foot forward. But you will need to do it again during the interview process.

You will likely have to interview with more than one person, and possibly go through several rounds, before a decision is made. Companies know how important selecting a new hire is and that the process is more art than science. Several key people may want to size up the applicants, which is why the multiple rounds of interviewing are used to whittle the pile down to the final candidate. Even then, you may be invited to another round as a final check—just to make sure they have made the right choice. Don’t be surprised if along the way you are also asked to take a written assessment test. There are tests that measure everything from aptitude to personality, and companies use them often.

Before you run the gauntlet, however, you should understand what hiring organizations are trying to accomplish when they interview candidates. Here again, the process is not about you. The companies want certain attributes in the person they hire, and they try to determine which of the candidates will most likely deliver for them. At the end of the day, they make their best guesstimate of who can provide the most value at the price they are willing to pay. Your job is to convince them that that person is you.

Be Relaxed and Be Prepared: The Job Interviewee’s Motto

An interview is a form of examination. Employers test candidates to see which one best meets their needs. Experts on testing agree that to achieve your maximum performance, you must relax. That is, you should go into interviews with an uncluttered mind. This advice is given for every kind of test, from driver’s licenses to college entrance exams to employment tests.

How do you relax? One of the keys to relaxation is feeling the comfort that comes from being well prepared. Solid preparation breeds the confidence that you will perform at your highest level. It also helps you be flexible so that you can answer any type of question thrown your way.

For example, Gail was midway through a daylong set of interviews before she realized a major flaw in her preparation. The interviewers’ questions were unexpectedly negative. “What have you failed at in your career and why?” “What kind of people do you least like working with?” “What is the best way to fire someone?” After a while she could not remember what answers she gave or whom she gave them to. Her prep time had been spent reading books on interviewing and memorizing what the authors promised would be “winning answers to tough interview questions.” Yet her rehearsed answers felt disconnected from her personal experiences. “There has to be a better way,” she thought.

You can divide the preparation for interviews into three categories: interview protocols (accepted etiquette), structures (the different kinds of interviews you are likely to encounter), and content (the questions themselves). Preparation for the first two types requires minimum memorization. The third takes advantage of the work you did when you developed your résumé and saw yourself in terms of the value you create. But let’s examine each of these types in turn.

Protocols: Accepted Etiquette

This section covers some rules of the road that most companies abide by and contains helpful hints that are easy to remember. Now is also a good time to clear up some common misconceptions.

BE ON TIME

Sometimes people are confused about what “on time” means. The safe answer is that being on time means getting to the interview somewhere between fifteen minutes and an hour before the interview is to start. You may intuitively sense that showing up an hour early is inappropriate and potentially awkward. For instance, you could accidentally bump into candidates who have been scheduled ahead of you, with appointment spacing far enough apart to avoid chance meetings. Similarly, you risk having the normal operations of the office conducted around you, as you sit and wait for an extended time. Arriving too early also gives you too much time to kill, especially if the interview starts late. That extra waiting time will likely heighten your anxiety. Yet you don’t want to cut it too close or you’ll risk being late.

Confused? Don’t be. “On time” means more than one thing. In one sense, it is the time you need to be available to the interviewers. In another sense, it is the time you should be near the facility but beyond the immediate physical environment of the interview location.

Barney had to rush to catch a taxi and, upon arrival, he made a mad dash up two flights of stairs to be “on time” for his 2:00 interview. He made it with three minutes to spare—or did he? A normal level of pre-interview anxiety and the summer heat combined to produce a shower of sweat dripping from his face during the entire interview. His careful preparation evaporated in the swelter of physical discomfort. He was on time but too late to interview effectively.

Take the time before the interview starts to get the physical lay of the land and do last-minute preparation, such as reviewing your notes and making sure your cell phone is turned off. Under these more relaxed circumstances you can plan your arrival to the general vicinity of the facility, beyond the immediate physical environment of the interview and up to as much as an hour ahead. Then, be at the interview location about fifteen minutes before the interview is scheduled to begin. Of course, that brief time should be adjusted if you have been told to arrive early to fill out paperwork. If the interview is located in another city or is in an unfamiliar part of town, you may want to make a dry run to the interview site the day before.

APPROPRIATE ATTIRE

What to wear? Dress guidelines for an interview vary slightly for men and women. Men have fewer choices—generally, a dark business suit, a white long-sleeve shirt, a color-coordinated tie, black socks, and black lace-up dress shoes. Modest variations to this standard are generally acceptable (e.g., blue shirt and dark loafers) but are less safe. It is, of course, possible to show your personality or fashion sense and still be appropriate. That could be something as small as the color of your tie or even the type of knot. But the advisability of this depends on the industry—some corporate settings are more rigid or conservative than others. Generally, self-expression is welcomed in less conservative industries. The best approach is to consult someone in human resources for advice on what is appropriate. When in doubt, however, it is better to be too conservative than too casual.

Other grooming tips include being clean shaven or with neatly trimmed facial hair (no facial hair is the safest), having neatly groomed hair, and wearing no flashy jewelry or loud cologne. If you visit any reputable men’s clothing store, you’ll get good advice about what to wear. If you are shopping, tell the salesperson you need a suit and coordinating components for a job interview, and the sales associate will help you pick an appropriate wardrobe.

For women, whose choices are broader, a dark business suit (with knee-length skirt) usually works best. Hair should be worn off the face and neatly pinned, as needed. An interview is neither the time nor the place for frilly blouses or a display of cleavage. As with men, skin-piercing decorations, save for modest earrings, are no-no’s. Strong perfume or cologne is also to be avoided.

Finding the appropriate dress for an interview is tricky because we are a diverse society, with different cultural and religious norms. If your clothing and grooming habits differ from generally accepted norms, check with the company so personnel will not be surprised by your appearance—at least they can communicate what they understand to be acceptable. If you already have multiple piercings of the ear or other visible parts of your body and/or tattoos, you may want to dress in a way that does not draw attention to them. Remove any adorning jewelry and cover tattoos, if possible.

What should you do if a company’s official dress code is business casual or less? You will, from time to time, encounter this situation, as Bill did when he interviewed to be a project leader at a Silicon Valley company. When asked, the recruiting manager and search consultant told him that business suits were specifically forbidden, and that the company’s president and all the others he would meet would be wearing blue jeans. High-tech companies in particular often go to considerable lengths to create informal work environments at every level in the organization, and this also applies to visitors. And these companies are not shy about informing visitors about their dress code. Most companies have not gone that casual, but many do allow employees to come to work dressed “business casual.”

So what does “business casual” mean? Claudia thought she covered the subject when she asked a representative from HR what the company’s dress code was. “Business casual,” he said. She ended up inappropriately dressed for her interview. A better approach would have been to inform HR how she intended to dress and get a specific sign-off on that. “I understand your work attire is business casual. Is that the expectation for those coming in for interviews?” Absent more specific information, play it safe and dress in the more formal business style.

Also, remember that companies mean dramatically different things by “business casual”—it can be anything from dress slacks and sport jackets to blue jeans. At all times, however, it means crisp, neat, and appropriate, even for a chance meeting with company VIPs or the CEO. In any regard, avoid the extremes. You should not look as if you are headed for either a night at the opera or a day at the beach. Likewise, avoid the extremes of tight or baggy clothing. When you think about business casual, think classic rather than trendy.

On occasion, you may have a job interview after normal working hours. If the dress required for the interview is different from your current working environment’s and you don’t have time to change, different attire at work could be a telltale sign you’re headed for an interview. Let the interviewer know how you will be dressed and why. The person will likely understand.

What about job fairs? Job fairs are an economical way for companies to search for talent, especially for entry-level white-collar positions. The expected attire is usually listed on the promotional materials accompanying the fair. When “business attire” is specified, the aforementioned guidelines should suffice. A “business casual” designation can, however, lead to all sorts of difficulties. Because recent graduates often go to job fairs, many college and university placement centers have published guidelines for students to follow. The one presented in Figure 4.1 is that offered by Career Services, at Virginia Tech University. (For any updated version for the dress code visit www.vatech.edu and search “business casual dress code.”)

FIGURE 4.1 Business casual dress guidelines.

Business Casual Guidelines for Men and Women

Business casual is crisp, is neat, and should look appropriate even for a chance meeting with a CEO. It should not look like cocktail or party or picnic attire. Avoid tight or baggy clothing.

Basics: Khaki or dark pants, neatly pressed, and a pressed long-sleeved, buttoned solid shirt are safe for both men and women. Women can wear sweaters; cleavage is not business-appropriate (despite what you see in the media). Polo/golf shirts, unwrinkled, are an appropriate choice if you know the environment will be quite casual, outdoors, or in a very hot location. This may not seem like terribly exciting attire, but you are not trying to stand out for your cutting-edge look, but for your good judgment in a business environment.

Shoes/belt: Wear a leather belt and leather shoes. Athletic shoes are inappropriate.

Cost/quality: You are not expected to be able to afford the same clothing as a corporate CEO; however, do invest in the quality that will look appropriate during your first two or three years on the job for a business casual environment or occasions.

Details: Everything should be clean, well pressed, and not show wear. Even the nicest khakis after 100 washings may not be your best choice for a reception. Carefully inspect new clothes for tags, and all clothes for dangling threads, etc. (as with interview attire).

Use common sense: If there is six inches of snow on the ground and/or you are rushing to get to an information session between classes and you left home 12 hours earlier, no one will expect you to show up looking ready for a photo shoot—they’ll just be happy you made it. Just avoid wearing your worst gym clothes and jeans. If you show up at an event and realize you’re not as well dressed as you should be, make a quick, pleasant apology and make a good impression with your interpersonal skills and intelligent questions.

SPECIFICS FOR MEN’S BUSINESS CASUAL

Ties: Ties are generally not necessary for business casual, but if you are in doubt, you can wear a tie. It never hurts to slightly overdress; by dressing nicely, you pay a compliment to your host. You can always wear the tie and discreetly walk by the room where the function is held; if no one else is wearing a tie, you can discreetly remove yours.

Shirts: Long-sleeved shirts are considered dressier than short-sleeved and are appropriate even in summer. Choosing white or light blue solid, or conservative stripes is your safest bet. Polo shirts (tucked in, of course) are acceptable in more casual situations.

Socks: Wear dark socks, mid-calf length so no skin is visible when you sit down.

Shoes: Leather shoes should be worn. No sandals, athletic shoes, or hiking boots.

Facial hair: Just as with an interview: Facial hair, if worn, should be well groomed. Know your industry and how conservative it is; observe men in your industry if you are unsure what’s appropriate or are considering changing your look.

Jewelry: Wear a conservative watch. If you choose to wear other jewelry, be conservative. Removing earrings is safest. For conservative industries, don’t wear earrings. Observe other men in your industry to see what is acceptable.

SPECIFICS FOR WOMEN’S BUSINESS CASUAL

Don’t confuse club attire with business attire. If you would wear it to a club, you probably shouldn’t wear it in a business environment. Also, most attire worn on television is not appropriate for business environments. Don’t be deluded.

WHAT TO TAKE TO AN INTERVIEW

Keep it simple. You’ve been called to the interview and your desired impression is of an organized, streamlined person. Trying to quickly retrieve what you need from a cluttered briefcase filled with papers is awkward. Rustling through loose papers gives the appearance of disorganization and forgetfulness.

Start with a black leather portfolio binder; a pad of lined notepaper; two ballpoint pens (in case one fails); a schedule of whom you are to meet and their titles; your notes; a list of references; extra copies of your résumé; and business cards, if appropriate. Using business cards can be tricky if your current employer doesn’t know you are interviewing, or if the information on the card is no longer accurate—that is, you no longer work at the address listed on the card. People generally understand if you tell them to contact you at work “with discretion.” Remember, if you are using a company phone, or computer, some employers track Internet and phone usage. In fact, having old business cards is a constant reminder that you are between jobs. If you are just starting out in your career, nobody will expect you to have a business card. Allow the contact information on your résumé to suffice.

If you decide to take more items to your interview, use a briefcase. But don’t use the extra space as an invitation to add clutter.

YOUR LIST OF REFERENCES

You should have your list of references available at the interview, even though you will usually be allowed additional time to submit them. If it is too early in the process, you may not be asked. But having such a list handy shows organization and forethought.

Sometimes companies will specify that they want references from those who have played particular roles in your professional life—supervisor(s), colleagues, and the like. When particulars are not specified, the most desirable references include your direct supervisors, clients, colleagues, and subordinates—all people who will have firsthand knowledge of your work.

Students preparing for an interview have roughly the same priority order, but with a little more flexibility. For example, deans and other university officials with whom you may not have worked directly or had only limited contact can be valuable additions to a list of references. The same is true for parents of roommates and other college-related acquaintances. However, references from your parents or from other kinship relations won’t help your cause and are considered inappropriate.

Reference checkers fully understand that you will ask for references only from those you trust will give you positive recommendations. That is why a negative or even a lukewarm recommendation quickly becomes a red flag that could signal problems and destroy your chances of getting the job. Be sure you get permission from people ahead of time before adding them to your list, and make sure they are willing to give you a positive recommendation. Don’t be afraid to ask them directly, “I am in the process of applying for jobs at a number of companies and was wondering if you are in a position to give me a strong recommendation?” If they are willing but you sense hesitation, accept the offer to help but think twice about adding them to your final list.

You should also let your references know that you will use them only when you are a serious candidate for a position. Companies do not enjoy reference checking and will do it only for those candidates who are on the short list. However, it has become common practice to check candidates’ online profiles (Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, etc.) at the very beginning of the interview process.

Otherwise, when the company checks your references, take that as a strong signal you have made the final list and a job offer could be forthcoming, although there are exceptions. For example, Teach for America requires reference letters for candidates before they are invited for interviews. From there, it is still a steep climb to a final offer. Regardless, a request for references indicates that you have moved up the Job-Search Pyramid, and your chances of acceptance have improved accordingly.

COACH YOUR REFERENCES

Don’t be shy about coaching your references on what to say. Return to the exercises you used to prepare your résumé. Here is another opportunity to put value creation to work on your behalf. The match between your value-infused accomplishment statements and the position description will likely tell you what the hiring organization wants to hear from a reference. For example, if the position calls for someone with strong project-management skills, leadership, and/or political savvy, you should coach your references to comment about your strengths in those areas as they experienced them.

Especially, be sure to thank your references for their help at the same time as you prompt them. A typical note from you might read: “Thanks for serving as a reference. I understand they are particularly interested in strong leaders with good project-management skills—you know, someone who has the political savvy to get things done. Any comments you could make about these would be helpful. Also, let me know if you need additional information about what I have accomplished in these areas.”

Additionally, encourage your references to use the language companies use when they describe the characteristics they are looking for in the candidates. That is the value they look to create, and your references can help you greatly if they describe your strengths in those terms.

OBTAIN SECONDARY REFERENCES

Staffing pros know that the deck is stacked against finding out anything of significance from references that are volunteered by the candidates. Candid references are hard to come by. Consequently, they rely on secondary references to provide more accurate assessments. These are often found through the initial list you provide. After the call to a reference has been completed, an interviewer may ask, “Are there other people you know who might be familiar with his [her] work?” It does not happen often, but it is a good possibility and you want to be aware of and deal with this possibility ahead of time if you think it is appropriate.

One way to accomplish this is to provide your references with a secondary list in the event they are asked. These people should be treated the same as those on your primary list. That is, you get their permission, you make sure they are able to give you a strong reference, and you coach them to cover things of value to the hiring organization. Don’t delineate the two lists for your references or the company. Do not refer to them as “primary” and “secondary,” or even mark them with an “A” or a “B.” Just tell all your references that they will be contacted only for positions for which you are a serious candidate. It is okay to refer to your secondary list as “Additional References.”

The header for your list of references is usually the same as the header for your résumé except that it specifies that what comes below are “Personal References.”

MICHELLE STREET, CPA

9501 Any Street

Chicago, Illinois 60600

312-555-0000

[email protected]

Personal References

The contact information for each reference should be formatted as follows:

Mr. Paul Neumann

Director, Financial Analysis

IBM

123 Big Blue Drive

Ossining, New York 12345

(555)555-5555

Former Supervisor

Notice that the e-mail address is not included. Safety walls will sometimes make it difficult for outsiders to connect with your references if they have not previously exchanged e-mails. That is, company spam filters often do not allow these e-mails through to the intended recipient. Check with each of your references to see if that is the case. If not, include their e-mail addresses on your reference list.

FOLLOW-UP THANK YOU

You should follow up every interview with written correspondence to the hiring manager and/or whoever formally represented the company during the interview process. Differences of opinion exist on the way to do this, varying from formal written letters to e-mails and even handwritten notes. The main point is that the medium used is less important than the content and intent. The purpose of follow-up communication is to thank company representatives for their time, confirm the next steps and time frames, review any points that need to be emphasized, and deliver on commitments made during the interview.

The sample follow-up letter in Figure 4.2 is in the format of a formal typewritten letter and contains all of these elements. If the company’s culture accepts e-mails as formal communications (many do), then an e-mail response will suffice. If you are unsure, however, a formal typewritten letter is the safest approach. Handwritten notes are generally not recommended, but it is up to you. Sometimes a handwritten note to a “behind-the-scenes” coordinator is a nice touch and contributes to the overall positive impression. This can also be an effective way to stand out at job fairs, where company recruiters meet as many as 100 different candidates.

Structure: Interviews, Tests, Tours

Your objective in each interview situation is the same: to stand out. If you are an effective listener, your chances are greatly improved. However, listening is hard work, and not everyone knows how to do it effectively. The best technique is to listen to the interviewer’s question all the way through, pause briefly, and articulate an answer. Far too many people start formulating an answer before the interviewer has finished asking the question. It is as if they are afraid there will be a moment of silence during the course of the interview.

FIGURE 4.2 Sample follow-up letter.

Michelle Street

9501 Any Street

Chicago, IL 60600

Mr. John Wayne

Vice President, Financial Planning

ACME Corp. 1111 A Street

New York, NY 00000

March 12, 2011

Dear John:

I just wanted to drop a quick note to thank you and your team for the opportunity to interview with ACME. The position sounds interesting and is very much in line with my career interest and ambition.

During the course of the interview a question came up as to whether the position is large enough in scope to hold my attention for an extended period of time. I think there is plenty to learn and would have no reason to try to rush to another assignment. My commitment will be to add value for as long as possible in any assignment I have. If you have questions about this, or other aspects of the interview, please feel free to contact me. I would be pleased to continue our discussion.

I understand you will finish interviewing next week and anticipate a final decision shortly thereafter. I will touch base with you the week of April 5 to see if the process is still on track.

Again, thank you for your time and interest.

Regards,

![]()

Michelle Street

Impatience creates problems that do not help your candidacy. First, you may rush forward with half-baked answers that do not respond to the intent of the question. Poor listeners also give the appearance of not being able to understand the question. There is a difference between offering assured answers that demonstrate command of the subject and shooting from the hip. Finally, some interview situations absolutely demand that you listen to the entirety of what is being asked before responding (video interviews are an example). You must incorporate good listening habits into your overall approach to interviewing.

Here is a practice tip. The next time you are among friends (perhaps giving someone an update on your job search), practice listening to each of their questions through to the end, pause for a moment to think about what you want to say, and say it. You will likely have a smoother, more fully satisfying conversation than normal. When you listen to questions all the way through, you will discover that many of them were asked rhetorically—that is, the listener sees the answer as selfevident. It is important to avoid trying to answer rhetorical questions, and the best way to do that is to listen to the entire question. This simple exercise will help you make your answers more organized, concise, and on target—all desirable outcomes in an interview.

Interviews can be structured in several ways, and you have to perform well in all of them. Kara expected that her day of interviews would feature a series of traditional one-on-one conversations. She knew several other candidates were interviewing that day, but she never thought they would be brought together for a group session that pitted them against one another. Totally surprised, she could not help showing her dismay about the situation, and she performed poorly in the balance of the one-on-one interviews. When you are preparing for an interview, expect the unexpected. Your familiarity with the different types of interviews can help you manage the unexpected.

The types of interviews mentioned here represent the vast majority of types you are likely to encounter. The message is, do not be surprised by the different ways you may be assessed, always be on guard, and go with the flow.

TRADITIONAL ONE-ON-ONE INTERVIEWS

The interviews you are most likely to encounter will be one-on-one conversations. In fact, an entire day can be taken up with speaking to various company representatives about the job opening. Don’t be surprised if the first interview is with someone from human resources whose sole responsibility is to determine if you should be passed forward to others that day or not. When candidates come across as particularly well suited for the opening, they can be passed forward to other interviewers right away (very often to those who can make immediate hiring decisions). Other times, there will be a series of interviews, beginning with the initial screening. Companies use this screening method to avoid wasting management time with candidates who obviously won’t work out. Why should a company schedule a full slate of interviews for candidates who will not make it through the first round?

Interviews with multiple interviewers sometimes are opportunities for the company to screen successively for different things, including technical competence, organizational fit, background, familiarity with industry issues, and even overall likeability. The initial care you took to develop a focused résumé that linked your past accomplishments to a company’s needs pays additional dividends at this point. You are well prepared and you understand how your experiences fit with the value being sought by the company. You just need to present that value in a calm, collected manner.

INTERVIEWS OVER DINNER OR LUNCH

This is not a time to relax. Even over a meal, you are still in an interview situation. Companies often want to know how you act in social settings. Pay attention, listen, and follow the lead of your host, especially when it comes to alcohol consumption. For lunch, you should avoid alcohol altogether, even if your host chooses to imbibe.

The situation is slightly different for dinner. Follow the lead of your host by consuming alcohol only if he or she does. If your table of interviewers makes split decisions (some do and others don’t), you should abstain. You want to continue to concentrate on the questions asked, hear them all the way through, and formulate thoughtful answers. That works best when you are as sober as the person asking the question. If you do drink, try to stick with wine and a maximum of two servings.

By the way, don’t be overly concerned if you are dining at a formal restaurant with more knives and forks than you know what to do with. Most likely, the others are not sure, either. Generally, the way utensils are laid out intends that you use the outermost fork or spoon with each course, and proceed in toward the plate as each course is offered.

PRESENTATION INTERVIEWS

More common in academic settings or where intellectual property is an important part of the product the company or department produces, the presentation interview can be an ideal situation because (theoretically, at least) you are in charge of what you want to say. On the flip side, such an interview can be difficult if someone in the audience is hostile to your candidacy or insists on interrupting in a way that disturbs the flow of the points you want to make.

The best tactic for this interview type is to encourage interruptions and simultaneously explain, “I prefer that we cover things you are interested in rather than get through my presentation.” Most audiences will understand when interruptions are unreasonable and will side with the presenter.

GROUP COMPETITIONS

Companies sometimes organize a group session as a way to measure individuals’ performance under pressure. Usually, a group of candidates is given conflicting objectives, such as “win the group over to your particular point of view but help the group come to a decision within a specified time frame.” The advice is to play it straight. Make contributions to the group as you can, explain your point of view clearly, and do not force the issue. Dominating the group to the detriment of others or to the group as a whole is not the right approach, nor is failing to make any contribution at all.

GOOD COP/BAD COP INTERVIEWS

Some interview situations are intentionally structured to see how you react under a different kind of pressure. Sometimes an interviewer will be hostile and aggressive toward you. For example, you might hear:

![]() “Not sure why you came all the way for this interview. I hear the job’s already been filled.”

“Not sure why you came all the way for this interview. I hear the job’s already been filled.”

![]() “That last answer of yours was the worst I have ever heard.”

“That last answer of yours was the worst I have ever heard.”

At other times, more than one interviewer at a time is involved (usually two), in which one is hostile and the other is accommodating to see if they can goad you into inappropriate behavior, especially when the “bad cop” leaves the room. Generally speaking, you should underreact. That is, do not return the hostility or forget that you must do well on the interview, regardless of what new information is received or the demeanor of the interviewers.

TELEPHONE INTERVIEWS

The telephone is used most frequently to screen applicants before going to the expense of inviting them in for additional consideration. Still, congratulations are in order here because you have undoubtedly advanced further than many other candidates. The one major disadvantage of a telephone interview is that you do not receive feedback from the interviewer’s body language to help you interpret the situation. Careful listening becomes even more important.

For such an interview, choose a private room (at home, if possible) away from background noise and interruptions. The rules about clutter still apply. If your phone has a high-quality speaker, use it so your hands are free to take notes and retrieve documents as they are needed. The same is true if you are using a cell phone with a headset. However, when the call is first initiated, you should not use the speaker feature until you have received permission from the interviewer to do so. You can ask, “I would like to have my hands free to take notes. Do you mind if I put you on the speakerphone?”

VIDEO INTERVIEWS

Video interviews can be tricky because of the delay between the audio and video displays. If one participant does not wait until the other is done talking before responding, it throws the entire interview off, and it has the effect of people’s stepping on one another’s conversations. Waiting until the other person is finished speaking before answering usually avoids this problem. Also, be sure your surrounding environment is neat and uncluttered, and look directly into the camera when speaking. Dress as if the interview is being conducted in person.

OTHER INTERVIEW TYPES: ASSESSMENT TESTS, COMPANY TOURS, PANELS

Candidates may be asked to take an assessment test as part of the interview process. Some tests measure personality characteristics to determine if you will fit with the culture. An alternative test is a skills/intelligence tool that measures your ability to learn. You should play it straight and not try to “psych” the tests out. Answer the questions honestly and do not give answers you think they are looking for. You either have what they are looking for or you do not. You too want to know that the situation is the right one.

Similarly, serious candidates may be given a grand tour of a facility to meet with various heads in groups, who will likely be asked to provide feedback before the final hiring decision is made. This is a bit of a beauty contest in which employees are given the opportunity to ask questions. In these situations, your listening skills are fully needed to pick up on any issues the questioners consider important. This is not the time for bold proclamations or idle promises. A simple acknowledgment of the issues raised and a commitment to be responsive are usually sufficient.

In a variation of the grand tour, you may be interviewed by a panel. If possible, find out ahead of time who the panel members are, what roles they play, and what issues are important to them. You may want to jot their names down in order of how the panel is arrayed around the table. It will help you recall their names as you respond to various questions.

Content: Interview Questions

Interviewing is more art than science. The overwhelming number of interviews you participate in will not be conducted by highly trained experts. Even staffing professionals who fill positions for a living seldom have enough training to classify as expert interviewers.

Don’t think, however, that they do not know what they are doing. The lack of expertise simply means they don’t use the data taken from interviews to make scientifically valid distinctions between candidates. Savvy staffing professionals know that the impressions they get from interviews need to be verified in other ways. Much of the data garnered from interviews is used to eliminate people rather than to verify whether they are best for the job at hand. Interviewers are assessing such qualities as listening skills, general appearance, and one’s level of personal organization—all factors you should be able to handle if you have followed our advice.

Given the interviewer’s lack of interviewing expertise, don’t think that all questions are equally focused on distinguishing one candidate from another. Some questions are simply icebreakers—a way of getting started with little, if any, evaluative meaning intended, such as, “How was your trip in?” “Before we start, do you have any questions about what we have planned today?” “Do you have any questions about the materials I e-mailed you?”

Nevertheless, all questions should be taken as opportunities to add to an overall impression that stands up well against other candidates. Don’t engage in idle chatter about how you got lost on the way to the interview. If you need additional information, now is a good time to get it. If not, move on.

You should also be aware that some questions (more than interviewers like to admit) are just fillers. That is, they are asked for purposes of filling the time an interviewer has been given to complete the interview. These are largely unrelated to the information needed to make a hiring recommendation.

For every interview, however, there is a core group of questions that directly relate to determining if you are the right candidate for the job. These are the questions for which you must be prepared. For those who understand the principles of value creation, this is good news, on two counts. First, all the answers to these questions are the same, in that they are opportunities to talk about things of value to the employer. Second, you have already learned what those valued things are and have the language to describe them; you did this when you focused your résumé on the job at hand. But let’s return to those exercises and use them to prepare for the interview.

GENERAL INTERVIEW PREPARATION

Above all else, avoid overdoing your preparation. Do not try to be ready for every possible question you could be asked. An interview is not an exercise in rote memorization. If you treat it as such, you will likely come across as stiff and mechanical in your answers. You also stand a good chance of being unable to recall details on demand.

Your answers to questions need to reflect your own experiences and not be fabricated. Besides moral considerations, the truth is always easier to remember than a lie. In addition, when you tell the truth, the weight of being ethical is on your side. Similarly, interviewing is like most things in life: the more practice you have, the better you will become. Once you have experience interviewing, the answers will flow naturally and you will find the comfort and relaxation that comes with being well prepared.

Remember that jobs in the same industry or function have a certain degree of overlap. Preparing for one job interview goes a long way toward preparing for others. That is why, to gain experience, you should sometimes interview for jobs even if you suspect you will not become a final candidate or accept an offer.

SPECIFIC INTERVIEW PREPARATION

The best preparation for an interview involves three steps: (1) visit what a company is trying to accomplish when filling the job for which you are applying, (2) match your background against its interests, and (3) align your experiences to answer potentially difficult questions.

An interview is a test in which you demonstrate the relevance of your résumé to the job. Interviewers want to know what you have done and whether you can perform with distinction. Though there are many average performers, no company intentionally fills a position expecting average performance. The distinctions between candidates are based largely on price and performance expectations. Your chances of being noticed are improved if your résumé is written using the same language the company uses to describe the value it wants in filling the position. That is, an interview is an attempt to confirm that what’s on paper will be reflected in your performance on the job. Preparation for an interview should focus on the links between the experiences captured in your résumé and the expectations of the job. You can accomplish this in three relatively easy steps, as mentioned above.

QUESTIONS OF RELEVANT EXPERIENCE If you have been through interviews before, you may have noticed that interviewers have a copy of your résumé in front of them and they use it to structure the interview. A typical question might be: “I noticed that you were a project manager for ACME for five years. Tell me about that experience.” How do you answer this question?

First, listen to the question all the way through, pause, and formulate an answer. The answers to all interview questions should be regarded as opportunities to talk about things of interest to the interviewer. For example, if the position description calls for “strong project-management skills with a minimum of five years’ experience,” your answer might be as follows: “That’s where I developed strength in the area. A couple of projects in particular were important steps along the way….” Recall projects that were particularly challenging and describe the required additional skills, including leadership and political savvy.

Once you create the connection between your accomplishments and their interests, you will be able to bring these to life in the stories you tell about past jobs. These stories, though, should reflect what you have actually accomplished. They will be easier to remember and will stand the test of reference checking.

But what if the position description did not mention project-management skills? Suppose the question catches you by surprise? Relax and give a straightforward answer to the best of your ability. If project management is a subject you are uncomfortable discussing, ask for further clarification from the interviewer, such as, “What aspect of project management would you like me to speak to?”

At first, interview preparation may feel a little awkward. But you will get the hang of it quickly, especially when you use your alignment sheets as a guide rather than trying to commit them to memory. Your familiarity with the links between your background and their requirements can give you a substantial edge over other candidates. And the more you prepare, the more you can relax and perform at your highest level.

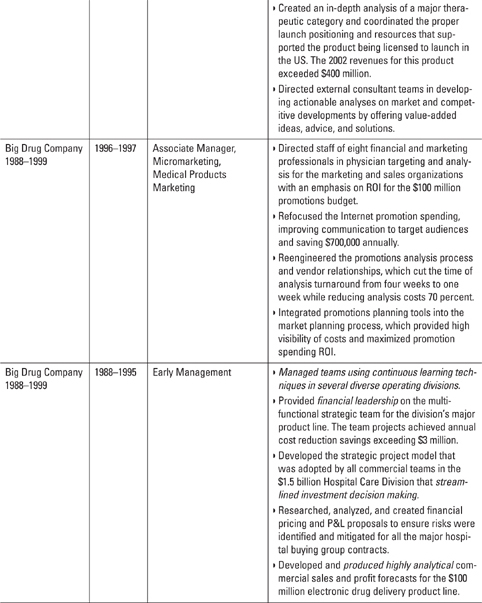

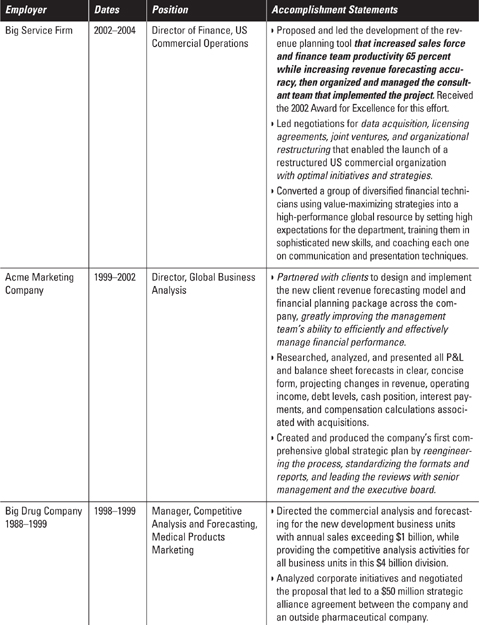

Let’s revisit the “key word” exercise and resume the examples of Michelle Street used in Chapter 2. Figure 4.3 lists ACME’s key words.

Michelle’s experiences in her accomplishment statements line up as indicated in Figure 4.4.

Again, notice the italicized portions of the accomplishment statements as they represent the use of key words to describe what the candidate has done. However, you should not try to force all questions to fit into your alignment. Interviewers are notorious for wandering off in directions unrelated to the task at hand. Your job is to recognize every opportunity to demonstrate that you are the best candidate for the job. And you accomplish that by good answers to the pertinent questions.

FIGURE 4.3 Key words from ACME Bank position description.

ACME Bank is an integrated financial services organization providing personal, business, corporate, and institutional clients with banking, lending, investing, and financial management solutions. We are deeply committed to a high-performance culture, one that values , and .

We reward our talented professionals with a base salary and competitive compensation package, life, health, dental, pension plan, 401(k), and an exceptional working environment.

SPECIFIC ACCOUNTABILITIES

Strategy

Understanding the corporate initiatives of the Bank, participate in or develop future-oriented strategies to maximize shareholder value as required

![]() to to .

to to .

Advisory

![]() Provide and by continually .

Provide and by continually .

![]() Work in partnership with the client to assist in optimal structuring of new initiatives and strategies. Ensure that structures comply with regulatory rules and guidelines.

Work in partnership with the client to assist in optimal structuring of new initiatives and strategies. Ensure that structures comply with regulatory rules and guidelines.

![]() Work as a valued business partner to , , and value-maximizing strategies—.

Work as a valued business partner to , , and value-maximizing strategies—.

![]() to clients on impacts of various business transactions (, etc.).

to clients on impacts of various business transactions (, etc.).

Governance and Analysis/Results

![]() .

.

![]() Prepare both formal and informal reports and analysis for the client as required to support strategic objectives, decision making, and solution resolution.

Prepare both formal and informal reports and analysis for the client as required to support strategic objectives, decision making, and solution resolution.

![]() Responsible for ensuring that .

Responsible for ensuring that .

![]() the annual .

the annual .

![]() and provide financial concurrence related to the approval of a .

and provide financial concurrence related to the approval of a .

![]() Attest as required to with applicable policies, including corporate policies and accounting policies. Provide input and concurrence to new policies impacting LOB.

Attest as required to with applicable policies, including corporate policies and accounting policies. Provide input and concurrence to new policies impacting LOB.

Support

![]() as required for new initiatives, process improvements, or technology implementation and development.

as required for new initiatives, process improvements, or technology implementation and development.

![]() Provide by , developing, and maintaining high-quality , and ensuring that processes are in place to do this.

Provide by , developing, and maintaining high-quality , and ensuring that processes are in place to do this.

![]() Responsible for providing ongoing and ensuring timely completion of annual review process.

Responsible for providing ongoing and ensuring timely completion of annual review process.

![]() Ensure that skill levels remain commensurate with the requirements of the position. Responsible for and taking appropriate actioaps.

Ensure that skill levels remain commensurate with the requirements of the position. Responsible for and taking appropriate actioaps.

![]() Key contacts: , Controllers Bank of Montreal Group of Companies, Finance departments.

Key contacts: , Controllers Bank of Montreal Group of Companies, Finance departments.

![]() Internal/external auditors, Regulatory agencies VBM.

Internal/external auditors, Regulatory agencies VBM.

![]() Support VBM initiatives by understanding , providing financial information, and performing as required.

Support VBM initiatives by understanding , providing financial information, and performing as required.

Knowledge & Skills

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

To explore this opportunity to join ACME Bank, visit our website and apply for position Job ID 55555 at www.acmebank.com.

QUESTIONS OF SHORTCOMINGS AND FAILURE You prep for tough questions a little differently because the wrong answer can have disastrous consequences. However, let’s be clear about what we mean by “tough.” A question that requires additional thought does not necessarily qualify as tough. For our purposes, a question is “tough” when a wrong answer can sink your candidacy. These are usually questions that attempt to solicit unprepared or spontaneous responses. If you are well prepared, they will be easy to handle. Yet giving a quick, unthinking response will cause an interviewer to pause in any consideration of your assets. Here is an example:

FIGURE 4.4 Examples of accomplishment statements.

Tough Q: “Tell me about your most significant failure on a job.”

Wrong Answer: “I can’t remember anything I have ever failed at.”

This common answer is a big loser. People who say they have never failed can be divided into two categories: those who have never tried anything challenging enough that failure was a possibility, and those who do not have good self-awareness. Companies usually do not want anything to do with people in either category. Fortunately, you do not have to memorize the answers to tough questions because there is no single, best answer. Knowing how to approach them is a far superior technique.

As much as possible, for answers to these difficult questions, keep your answers simple, direct, and positive—make them affirmations of your fit with or interest in the position. In the example above, acknowledge the failures or difficulties that you have since corrected. For example, “Early in my career, I needed better project-management skills. These developed as I took project-management courses and gained more practical experience….”

There are variations on this line of questioning. For example:

![]() Tell me about a time when you failed to deliver.

Tell me about a time when you failed to deliver.

![]() What is your greatest weakness?

What is your greatest weakness?

![]() What do you need to improve the most?

What do you need to improve the most?

In each case, the interviewer wants to know what action you took to improve your skills and whether there are any lingering issues. You answer all questions about failures and shortcomings as examples of ways you became better over time. Avoid any suggestion that a weakness or shortcoming still exists to the same extent it did when first brought to your attention. Plus, this is an excellent time to return to your alignment sheet and mention a specific example of something you accomplished, putting it in the context of the value the company is seeking in filling the position.

For example, Michelle Street’s résumé was, in part, written in response to the “key word” requirements that the successful candidate needs experience in training a staff. Here’s her response to the question, “What is your greatest weakness?”:

“Early in my career I was not as strong a leader as I needed to be. This showed up as impatience with staff any time we were under pressure to perform. Later, when I received the award for management excellence, it was obviously a team award. I led the team, but they did the work. I’m not sure we could have accomplished that earlier in my career.”

From time to time, an interviewer will persist and ask for something you need to get better at right now. You should pick something that you worked on previously—that is, treat all “weaknesses” as opportunities for continuous improvement. For example, Michelle might respond, “Leadership skills require constant work.”

QUESTIONS OF TIME GAPS Suppose the interviewer wants to know if there is a problem with you—perhaps how you work with people, if you have specific job-related skills, and so on. Because you’ve been out of work for a considerable time, the interviewer may suspect an underlying difficulty. The question may be indirect, but the objective is to find out why you were unemployed for a while.

What is considered a “long” time out of work varies, both with the economy and with individual situations. Recent college graduates can travel for up to a year without raising eyebrows. For more experienced workers, going more than a year between jobs qualifies as a “long” period.

No matter how long you have been out of work, you don’t need to apologize or dwell on the subject. If you suspect your unemployment will last longer than six or seven months (a reasonable time to look for work), stay busy doing jobrelated tasks or volunteer work. All of us want our next jobs to be the right one, so some amount of continued unemployment can be explained as a search for the right job. But you must show that you have stayed busy in areas related to the job. For instance:

Q. “I noticed you have been out of work for fifteen months. Why has it taken so long to find another job?”

A. “Some of the time is the result of looking for the right opportunity with a company like yours. I have also used this time to give back to my church [or whatever institution] as an active volunteer.”

Your answer will be stronger if your out-of-work activities have relevance to the skills required in the job. Again, look to your alignment sheet for guidance.

QUESTIONS ABOUT LEAVING YOUR LAST JOB People either leave a job voluntarily or are terminated. If you were terminated, you must work out with your previous employer how the termination will be characterized. Terminations can easily be positioned as voluntary leaves or job eliminations from restructurings. There is no disgrace in either situation. How you position that and what you say about it in the interview, however, are important.

The interviewer wants to know if you were fired from your last position and whether there is an underlying problem with you.

Q. “Did you leave your last job voluntarily?”

A. “I had a choice to make about whether I wanted to continue in a job with very little career upside. Since I needed to search for better opportunities full-time, I chose to look for a new position. If not, I would not have found this opportunity.”

Of course, you must be ready to comment on the ways in which your opportunities at your old job were limited without bad-mouthing your previous employer.

QUESTIONS ABOUT CONFLICTS WITH FELLOW EMPLOYEES Questions about your working relationships in previous jobs are designed to uncover your familiarity with and use of conflict-management skills. The best skill to have in this area is the ability to bring people together to discuss the issues, assign roles, and move forward toward getting the job done. Even if you are not in a managerial position, potential employers will want to know what you did to help reduce the level and intensity of conflict.

The move toward flatter organizational structures requires greater skills to influence others and manage without authority. The interviewer wants to know how you behave in those environments. For example:

Q. “Tell me about a situation at work in which there was conflict among employees and how you handled it.”

A. “One of our high-performing teams started bickering among themselves. Once I confirmed that others felt this way as well, I sponsored an off-site meeting facilitated by an outsider. It turned out that there was a lot of confusion about roles and responsibilities. Once these issues were clarified, the bickering stopped and productivity improved.”

The suggestions here are not intended to cover every possible question type. There are many more questions you could be asked, and you can’t, and shouldn’t, try to prepare for all of them. Be willing to occasionally be surprised and have to think on your feet. An uncluttered mind is far more important than having practiced the answers to all the questions anyone would ever think to ask.

QUESTIONS OF SALARY Questions about salary can be particularly vexing in an interview because a wrong answer can eliminate you from competition, as well as compromise your bargaining position. If your previous salary was higher than what the company wants to pay, it may pick someone for whom its position would be a nice step up in compensation.

Many companies avoid hiring white-collar workers at lower pay levels than they had previously because of the concern that they will continue to search and use the current job as a temporary position until they find something better. On the other hand, if your previous salary was substantially below the position in question, a company may try to hire on the cheap.

If at all possible, deflect questions about salary and indicate that you would consider any offer the company thinks reasonable. If you are in a position where you can turn down job opportunities and wait until the right one comes along, you can afford to be more open about your salary requirements.

Some companies refuse to play the salary game and insist that you provide previous salary history or they will terminate your candidacy. If so, provide the information and proceed with the interview.

Questions for You to Ask

Always have a few questions ready to ask in return. Most interviewers will signal the end of the interview by asking, “Do you have any questions?” This does not mean you should wait until the end to ask your questions, however. If a question arises in the normal course of the interview, go ahead and ask it. However, hold a few back for the end.

This is not the time to show off your knowledge of recent company events in the news or to cover an arcane aspect of the industry. Follow the axiom to keep it simple. End-of-interview questions serve three purposes: to give you an opportunity to talk about aspects of the job for which you are a good fit but may not have been covered, to clear up any confusion, and to set the stage for follow-up steps. Though called “questions for the interviewer,” the end of the interview is really a time for you to make affirmative statements about your candidacy and obtain the information you need for effective follow-up.

QUESTIONS THAT EMPHASIZE GOOD FIT Perhaps you are satisfied with how well the interviewer understands your fit with the job. If so, no questions in this area are required. The best way to determine that is to consult your alignment sheet. At this point, it is okay to actually pull the sheet out and glance over it to see if anything has been missed. You do not want to rustle through papers looking for the sheet. It should be right at your fingertips. For example:

Q. “I have covered what I need. Do you have any questions for me?”

A. “Let me check my notes.” [Retrieve your alignment sheet and take a few seconds to review.] “I noticed in the position description that you wanted someone with experience in …. That’s one of my strengths, and I want to make sure I have shared those details with you.” [Unless interrupted, provide a brief description of what you accomplished.]

Or, the response might be:

A. “Let me check my notes. Earlier you asked me about …. I would like to add to that answer.”

The second response gives you the opportunity to revisit an answer you want to improve on.

You might also ask questions as a way to clear things up. In a sense this is the same as the second response above. The interviewer’s body language may have shown disagreement or confusion about an answer you gave. Now is your opportunity to clarify any misunderstanding. However, do not accuse the interviewer of misunderstanding or disagreeing, even if you feel he or she is at fault. Take responsibility for it by saying, “Perhaps what I said wasn’t as clearly stated as it needed to be.”

QUESTIONS ABOUT THE NEXT STEP You structure the end of the interview in a way that allows you to take positive action in the event you do not hear back in a timely manner. Hiring decisions are seldom made in the time frame initially laid out by the company. Candidates are often left twisting in the wind—or at least it feels that way. For you, the decision is monumentally important, whereas a company will likely have competing priorities. End the interview in a way that gives you permission to contact the company without appearing to be either overanxious or overbearing. For example:

Q. “I have covered what I need. Do you have any questions for me?”

A. “Let me check my notes [if appropriate]. When do you expect to make a decision?” [Wait for an answer.] “I will follow up in a couple of weeks just to check in.”

Or,

A. “My understanding is that you plan to make a decision by the middle of next month. Meanwhile, feel free to contact me if you have additional questions or something comes up. I will follow up as well.”

![]()

![]()

![]()

You have covered the basics of interviewing in a way that will help you prepare and relax so as to do your very best. The memorization requirements have been kept to a minimum. Nobody will ever know all of the answers to every possible question that can be asked. But if you know what is valued in the position, you can prepare for that moment when you can provide an answer that tells them what they really want to know.