The Shackleton Saga

The saga of Shackleton’s Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition has been told many times. I first encountered the story some fifteen years ago when a friend—knowing my interest in survival accounts—gave me a copy of Alfred Lansing’s Endurance. I was so captivated by the story that I simply could not put it down. I knew that the account, while an engaging tale of adventure, was something more. It was a powerful metaphor that I could use to help leaders who were taking their organizations to The Edge.

A number of other excellent books on Shackleton are listed in Part Three, including Caroline Alexander’s volume with superb photographs. My goal in writing Leading at The Edge is not to duplicate these historical accounts, but rather to examine the story in a different way using the lenses of leadership and teamwork.

Later chapters will highlight important aspects of the story, each one illustrating how Shackleton and others used the ten Leading at The Edge strategies. These illustrations will have more impact, however, if they are understood in the context of the overall story. This account, therefore, provides an overall chronology of key events, many of which will be explored in more detail in subsequent chapters.

Setting the Stage

The Shackleton expedition’s extraordinary tale is one of the most exciting adventure stories of polar exploration. It is a story about a leader and a group of explorers who endured conditions of hardship and deprivation more extreme than most of us can even imagine.

To help frame the story, consider this question: Have you ever been cold? I mean really, really cold? Try to recall the coldest, most miserable time in your entire life. It might have been on a camping trip when you got caught in a hard rain and had to spend the night in a wet sleeping bag. It might have been while waiting for a tow truck in the winter with a dead battery.

Now, hold that feeling and imagine that someone said to you: “You’re going to live this way for the next 634 days. You’ll be out of touch with the rest of the world, your family will have no idea whether you are dead or alive, and you will be hungry to the point of starvation.”

If you can conjure up that feeling of coldness and desolation, it will give you some sense of the conditions faced by Ernest Shackleton and the members of his Trans-Antarctic expedition.

The adventure began with an advertisement, perhaps apocryphal, that appeared in the London papers:

Men wanted for Hazardous Journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.1

Who in the world would volunteer for this journey? Some of you reading this book might feel that this is your job description, and that you have already volunteered. Amazingly, thousands of would-be explorers came forward, each wanting to join Shackleton’s expedition.

But what were they signing up for? Shackleton’s mission was the first overland crossing of the Antarctic Continent. He had a clear vision and a plan for how to achieve it. Shackleton intended to sail from London to Buenos Aires and then to the island of South Georgia. From South Georgia, the expedition would enter the Weddell Sea, cross Antarctica, and exit on the other side, where a ship would be waiting. Having calculated the times and distances, Shackleton believed the transcontinental journey could be completed in 120 days.2 One way of understanding what he was trying to accomplish is to imagine walking from Idaho to Texas, except the geography is dramatically different.

The terrain of Antarctica is depicted well in a passage from Stephen Pyne’s The Ice:

Ice informs the geophysics and geography of Antarctica.… Out of simple icy crystals is constructed a vast hierarchy of ice masses, ice terranes, and ice structures. These higher-order ice forms collectively compose the entire continent: the ice bergs: tabular bergs, glacier bergs, ice islands, bergy bits, growlers, brash ice, white ice, blue ice, green ice, dirty ice; the sea ices: pack ices, ice floes, ice rinds, ice hummocks …; the coastal ices, fast ice, shore ices, glacial-ice tongues, ice piedmonts; the mountain ices: glacial ice, valley glaciers, cirque glaciers …; the ground ices: ice wedges, ice veins, permafrost; the polar plateau ices: ice sheets, ice caps, ice domes …; the atmospheric ices: ice grains, ice crystals, ice dust, pencil ice, plate ice, bullet ice.3

This description makes it clear: The surface of Antarctica is nothing but ice. The continent’s perimeter begins with an ice shelf, in places as tall as a ten-story building. Once past the shelf, there are other obstacles. There are ice hummocks—jagged ridges thrust upward like so many small mountains. Crevasses that can swallow a dog-sled team abound. And, then, there is the climate. The coldest temperature on Earth has been recorded in Antarctica: –128.6°F.

The Leaders and the Crew

Crossing Antarctica was a formidable undertaking. What kind of a person would attempt a feat such as this? Ernest Shackleton believed he was the person to do it.

Shackleton was an explorer who had already gained fame in Britain in 1909, when he came within ninety-seven nautical miles of the South Pole before he was forced to turn back because of physical exhaustion and a shortage of food.4 On that expedition, in a characteristic gesture, he gave one of his last biscuits to a comrade, Frank Wild.

The South Pole was reached in 1911 by Norwegian Roald Amundsen and then early in 1912 by the ill-fated expedition of Robert Falcon Scott. No one, however, had traversed the continent by 1914, and this frontier of exploration remained. Shackleton yearned for a challenge, and this was one of the few remaining arenas in which to test his skills.

Much has been written about Shackleton, but I believe the essence of his character can be found in the values transmitted by his family. The Shackleton family’s Latin motto, Fortitudine Vincimus (By endurance we conquer), was his rallying cry, and the expedition put his motto to the test.

Because he was the leader of the expedition, and because of his forceful personality, much emphasis has been placed on Shackleton. As in any complex enterprise, however, leadership was exercised by many individuals. In fact, a key theme of this book is the importance of mobilizing leadership from multiple sources.

One of the most important sources of leadership came in the form of Frank Wild, Shackleton’s old companion. Wild’s low-key style balanced Shackleton’s bold temperament, and they were so close they would finish each other’s sentences. This partnership, born of deep respect and shared hardship, would serve them well when both would be stretched to their limits to maintain the integrity of the expedition.

Wild and Shackleton selected twenty-five other explorers for the expedition. Complex and diverse, the group was composed of men with a range of temperaments; personalities; and technical skills, including medicine, navigation, carpentry, and photography. The team was also diverse in social class, ranging from university professors to fishermen, and in age. The oldest, McNeish, the carpenter, was fifty-seven.

Officially numbering twenty-seven, the full complement of the ship proved to be twenty-eight with Blackborow, the stowaway. When Shack-leton discovered that there was a stowaway aboard, he was furious and declared, “If we run out of food, and anyone has to be eaten, you will be first.”5 Despite this inauspicious start, Blackborow eventually became fully integrated as a member of the expedition.

Shackleton was also faced with the task of finding a seaworthy vessel to carry them south. He chose a barkentine-rigged ship, which he named Endurance, after his family motto. Built by a famous Norwegian shipbuilding yard, the vessel was powered by both steam and sail.

Endurance was specifically designed for polar travel, constructed of carefully selected wood to withstand the pounding of the ice. Unlike modern icebreakers, however, Endurance was not designed to ride over the ice but was constructed with a V-shaped keel.

The Adventure Begins

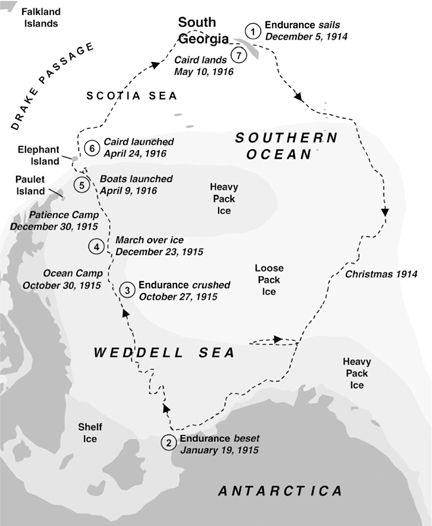

While Shackleton stayed behind to raise money, Endurance sailed at the end of August 1914 under the command of Frank Worsley. Shackleton joined the expedition in Buenos Aires, and they all set out for Grytviken, a whaling station at rugged South Georgia (Figure SS-1, map position 1 at the end of this chapter).

At the whaling station, Shackleton received disturbing reports that the ice had moved much farther north than usual. With these warnings, and knowing that wintering aboard was a distinct possibility, they sailed on December 5, 1914, with extra clothing and a great deal of apprehension.

Shackleton portrayed the scene:

The ship was very steady in the quarterly sea, but certainly did not look as neat and trim as she had done when leaving the shores of England four months earlier. We had filled up with coal at Grytviken, and this extra fuel was stored on deck, where it impeded movement considerably. … We had also taken aboard a ton of whale-meat for the dogs. The big chunks of meat were hung up in the rigging, out of reach but not out of sight of the dogs, and as the Endurance rolled and pitched, they watched with wolfish eyes for a windfall.6

As the ice thickened, the going became more and more difficult. As Worsley enthusiastically rammed the ship through the floes, Shackleton became increasingly worried by the lack of progress. They wormed their way through the “gigantic and interminable jigsaw puzzle devised by nature.”7

Trapped in the Ice

On January 19, 1915—forty-five days after their departure from South Georgia—disaster struck. The ice of the Weddell Sea closed around Endurance like a vise. The expedition was stuck, sixty miles from the Antarctic Continent (Figure SS-1, map position 2).

Working with picks, saws, and other hand tools, the expedition made two attempts to break free. The first time, with all sails set and engines on full ahead, the crew tried for hours and never moved a foot. In a second attempt, working from 8 A.M. to midnight, they advanced 150 yards. But they were still hopelessly stuck. The “elastic” sea ice prevented a solid blow from ramming a passage, and Endurance was trapped.8

On February 24, sea watches were canceled, and the crew resigned themselves to wintering on board. The men moved to a warmer between-decks storage area that they called “the Ritz.” Their only entertainment was a hand-cranked phonograph and Leonard Hussey, the geologist, who played his banjo and a homemade violin. As the days wore on, Endurance became caked with snow and ice. It would be difficult to imagine a colder, bleaker scene. In these extreme conditions, members of the expedition became closer than ever.

How did this happen? I believe the answer lies in Shackleton’s understanding of the absolute importance of managing the dynamics of his crew. He had learned from accounts of previous expeditions of the severe morale problems that could arise, and he made a number of conscious decisions to ensure the cohesion of the team. Foremost, as Endurance sat securely on the ice, Shackleton kept the crew fairly busy until the end of July 1915. At that point, deep in the Antarctic winter, high winds caused the ice pressure to increase. The ship heeled, the bilge pumps began to fail, water poured into the ship, and the stern was thrown upward twenty feet. As the ice moved relentlessly against the hull, both the timbers of Endurance and the crew’s sense of security began to crack.

Worsley, the captain, recalled:

Two massive floes, miles of ice, jammed her sides and held her fast, while the third floe tore across her stern, ripping off the rudder as though it had been made of matchwood. She quivered and groaned as rudder and stern-post were torn off, and part of her keel was driven upwards by the ice. To me, the sound was so terribly human that I felt like groaning in sympathy, and Shack-leton felt the same way. It gave me the horrible feeling that the ship was gasping for breath. Never before had I witnessed such a scene, and I sincerely hope I never may again.9

Endurance Goes Down

Day 327 of the expedition—October 27, 1915—marked the end of Endurance. The masts toppled and the sides were stove in, as shards of ice ripped the strong timbers to shreds. Frank Wild made a last tour of the dying vessel and found two crewmembers in the forecastle, fast asleep after their exhausting labor at the bilge pumps. He said, “She’s going boys, I think it’s time to get off.”10

Imagine yourself in Shackleton’s position. Your ship is crushed, and you are 346 miles from the nearest food depot on Paulet Island (Figure SS-1, map position 3). You have lifeboats and sleds, but they weigh almost a thousand pounds. Now what?

Shackleton proposed to head toward open water by undertaking a march across hundreds of miles of solid pack ice. Men in harness began pulling the lifeboats on sledges. The task was grueling, and after two days of hauling, the team had covered less than two miles.

Ocean Camp

Realizing that it was futile to go on, the men found a large floe more than half a mile in diameter, made camp, and came to a decision. They agreed to stay on the floe until the drift of the ice carried them closer to Paulet Island. They sat at Ocean Camp from October 30, 1915, until the end of December. So far, Shackleton’s leadership had kept the team intact. Now, however, it was more than a year from the time they had set sail from South Georgia. Morale was understandably low, and Shackleton knew that something had to be done to combat the growing sense of futility. On day 384, although they were still a long way from the sea (Figure SS-1, map position 4), they once more attempted to drag the boats across the ice to open water.

The Mutiny

This second sledge march was no more successful than the first, and it set the stage for what has come to be called the “one-man mutiny.” McNeish, the carpenter, refused to go on. He argued that the articles he had signed specified serving “on board” and, since Endurance had sunk, they were no longer binding. Despite a special clause in the articles that bound him “to perform any duty on board, in the boats, or on the shore,” McNeish stood his ground.11 He defied orders to march, so Shackleton was summoned, defused the mutiny, and enabled the expedition to move forward.

Patience Camp

Exhausted and discouraged because the ice was still impassable, the expedition crewmembers again made camp and waited. The men knew they had to get off the ice, but they had no sense of controlling their fate. Reginald James, the physicist, summed it up this way: “A bug on a single molecule of oxygen in a gale of wind would have about the same chance of predicting where he was likely to finish up.”12

They continued to deal with the anxiety of waiting, hoping to drift to open water. As their food supply dwindled, they stayed alive on a diet of seal steaks, stewed penguin, and their favorite: penguin liver. There were some moments of excitement, including a near-fatal encounter between Thomas Orde-Lees, the storekeeper and former Royal Marine, and a sea leopard.

By the beginning of April, the floe had shrunk from a half mile to 200 yards wide. With the floe literally cracking out from under them, the men wanted to launch the boats. But they knew that abandoning the floe prematurely might mean disaster: The unstable ice could close, crushing the boats and their only hope of survival.

Escape from the Ice

Finally, on April 9 (Day 491), the pack opened and the boats were launched (Figure SS-1, map position 5). The men tumbled into the three lifeboats, put out every available oar, and pulled with all their strength for open water. The temperature was so cold that when the waves broke over the boats, the water froze to the rowers’ clothes in an instant. The men bailed furiously, but the water rose quickly to their ankles and then to their knees. Blackborow, who was wearing leather boots, soon lost all feeling in his feet.

They were all emaciated, suffering from diarrhea, and desperately craving fresh drinking water. The first night they camped on a flat, heavy floe and fell asleep. Late that evening, “some intangible feeling of uneasiness” moved Shackleton to leave his tent. He stood in the quiet camp, watching the stars and the snow flurries. Suddenly, the floe split under his feet, and from the darkness he could hear muffled, gasping sounds. Shackleton ran to a collapsed tent and threw it out of the way, exposing a member of the crew who was struggling in his sleeping bag in the frigid water below. With a tremendous heave, Shackleton pulled him onto the ice, just as the two halves of the broken floe came back together with a crash.

As the winds and currents changed, the group was forced to change its destination four times during the five-and-a-half-day voyage. Finally, they found respite on a rocky, barren speck of land known as Elephant Island. The beach was only 100 feet wide and 50 feet deep, but for the first time in 497 days they were on solid ground.

Elated, but on the verge of collapse, the men ate their first hot meal in almost six days. Given their enfeebled condition, even the most basic tasks were painful. They built shelters out of lifeboats, sails, and clothing. Unfortunately, the shelters were constructed on snow that had been mixed with hundreds of years of penguin guano. Body warmth and the heat from a blubber stove melted the guano, and the crew soon found themselves wallowing in a foul-smelling yellow mud of penguin guano. So they had made it to safety—sort of—but what now? There was only a small food supply on the island—a few penguins, some seagulls, shell-fish, and some elephant seals. Still, the chance of rescue was slight and another decision loomed: whether to stay and wait for rescue, or to sail for help. If you sail, where do you go?

The Scotia Sea

There were no good options, and the danger of running out of food also weighed heavily on Shackleton. He confided in Worsley: “We shall have to make the boat journey, however risky it is. I’m not going to let the men starve.”

Shackleton decided that part of the crew would sail for help. Because the region’s gale-force winds blew from west to east, he elected to make the 800-mile run to South Georgia, sailing through the most treacherous stretch of water on the planet, with winds of hurricane intensity and enormous waves.

Shackleton chose the James Caird, the one lifeboat that was the most seaworthy, and attempted to create a vessel that would survive the voyage. Although McNeish was a troublemaker on occasion, he was also a skilled and creative carpenter. His ingenious solution for decking and outfitting the lifeboat for this risky journey proved invaluable. Shackleton selected five members of the expedition to sail with him. After a farewell breakfast, all hands mustered to launch the James Caird on Day 506 (Figure SS-1, map position 6).

The next sixteen days were even more harrowing than the journey to Elephant Island. The boat was constantly pounded by immense waves known as Cape Horn Rollers. Each watch, one of the men was forced to risk his life to chip away ice that was constantly forming on the deck and lines.

On May 10, 1916, the exhausted sailors sighted South Georgia. As they made their landing, the rudder fell off the James Caird, but by late afternoon Shackleton and his companions were standing on the island they had left 522 days earlier (Figure SS-1, map position 7).

Across the Glaciers

A safe landing was the good news. The bad news was that they were on the wrong side of South Georgia, an island abounding with uncharted and treacherous glaciers. Shackleton and the two best able to travel proceeded overland to reach the whaling station of Grytviken at Stromness Bay. It took the men three days and nights—each filled with danger and enormous physical challenge—to reach the station.

The men left behind on the far side of South Georgia were soon rescued. Shackleton and five others were finally safe. Back at Elephant Island, however, conditions were desperate. Frank Wild, whom Shackleton had left in charge, worked desperately to keep up the crew’s spirits. After four months of waiting, however, the men were wondering if they would ever be found.

The Rescue

Shackleton struggled to get help for the rest of his crew, making three attempts in three different ships. Finally, at the end of August—128 days after the launching of the James Caird—he succeeded on the fourth attempt. The timing was providential: The pack ice opened for only a few hours, just enough time to get a boat ashore and to complete the rescue.

Captain Worsley’s final journal entry reads:

Rescued! August 30, 1916

All well! At last! All ahead full.

Worsley13

With that entry, the saga of Ernest Shackleton and the men of the Trans-Antarctic expedition ended, 634 days after their departure from South Georgia.

Every time I relive this story, I want to give these explorers a round of applause. I want to applaud them not just because they made it to safety, but because of the extraordinary leadership and teamwork they exhibited. Not only did they survive, they all survived with a unique level of caring and camaraderie.

What was it, exactly, that made Shackleton such a great leader? What was it that enabled Shackleton and his team to overcome such seemingly insurmountable obstacles? The chapters that follow provide answers to these questions.