11

Learning to Lead at The Edge

It’s never too late to be what you might have been.

—George Eliot

The ten strategies outlined in Part One of this book provide a roadmap for leaders who want to take their organizations to The Edge—to help them achieve their greatest potential. This chapter focuses on the personal dimension of the journey—the behaviors, attitudes, and ways of thinking about life that help individuals to realize their full potential as leaders. Specifically, it outlines a number of qualities and actions that—in my experience—contribute to living, learning, and thriving at The Edge.

Cultivate Poised Incompetence

When my son, Jonathan, turned sixteen, he got his own car, a Toyota Celica that was in good condition for a vehicle with about 90,000 miles on the odometer. Trying to be a good father, I spent a lot of time going over the importance of car maintenance, trying to remember everything my father told me to do.

Each parent stresses certain lessons or tasks as if they are the most important in the world. For my mother, it was choosing exactly the right word and pronouncing words exactly the way they were supposed to be pronounced. For my father, one of the central tasks in life was checking the engine oil and keeping an eye on the dipstick.

I was not as religious about watching the oil as my dad, but in an effort to be a good parent, I did my best to pass on the tradition to Jonathan. As a result, my son put all his teenage energy into getting the Celica into shape: washing; waxing; scraping off rust; dabbing on touch-up paint; and, most important of all, watching the oil.

Jonathan watched the dipstick like a hawk, waiting for his big moment to add oil. When the time finally came, I was inside playing my guitar. Jonathan came in, brimming with excitement, and asked for a funnel. I went out to the garage, got him one, and then went back to playing.

A little while later, he came in and said, “Dad, this one’s too big. I need a smaller funnel.” So I went out to the garage a second time and got another funnel, saying, “This should do it. It’s the smallest I have.” It never occurred to me to ask why he needed such a small funnel.

After a while, I went outside to see how he was doing. He had an extremely frustrated expression on his face. “What’s the problem?” I asked.

He pointed at the engine. I looked down and saw an extraordinary creation. It was a marvel of mechanical engineering. Jonathan had taken a roll of duct tape and attached a piece of glass tubing from his chemistry set to my small funnel. With this contraption, he was pouring oil … can you guess where? He wasn’t pouring it into the normal hole on top of the engine, but into the hole for the dipstick, which is about the size of a pencil. He said, “Dad, this is taking forever!” And it probably would have.

When I showed him the two-inch hole over the manifold that most people use to add oil, it came as quite a revelation. The story did have a happy ending. We finished the job in about three minutes, and we still laugh about Jonathan and the dipstick.

What’s the point of this story? Leaving aside my limitations as an auto mechanics coach, I can think of two. One is that—in the spirit of Strategy 10 (“Never give up”)—with enough creativity and determination, you can accomplish the mission even if your strategy is not perfect. Jonathan was getting oil into the engine, even if it was taking him a while to do it.

A second point is that developing any skill is a journey that starts at the beginning with a certain level of ignorance and incompetence. When we look at people who are exceptional at their craft, we often think they were born with that knowledge. One of the interesting aspects about getting older is that you find that some of your friends actually make it to positions of real responsibility—and you knew them when.

Two of my Naval Academy classmates fit this description. John Dalton became the Secretary of the Navy, and Chuck Krulak became the Commandant of the Marine Corps. Both were talented individuals who showed early promise. But when I saw them at the Pentagon, thirty years after graduation, with everyone saluting, I did a double-take. I knew them both from plebe year at Annapolis, when we were first learning how to spit-shine our shoes, and before they had distinguished themselves as exceptional leaders.

In doing research on Shackleton’s life, I discovered, to my amazement, that before his first trip to the South Pole he had never pitched a tent, he had never slept in a sleeping bag, he had never slept in a tent overnight, and he had never lit a Primus stove. He had never done any of these basic tasks and yet, eventually, he developed the skills to lead an expedition that would triumph over overwhelming obstacles in the most hostile environment on earth.

I do not recommend going to Antarctica without knowing how to set up a tent. I do know, however, that we all have to start somewhere. The first key to learning to lead at The Edge is this: Cultivate poised incompetence. You have to be willing to be incompetent in order to learn. Just because you don’t know what you are doing doesn’t mean you have to be embarrassed or upset or convinced something’s wrong with you.

There are countless stories of people who moved from incompetence to great proficiency: The Red Baron crashed on his first solo landing; Michael Jordan was cut from his high school basketball team; and in the beginning of his administration, Abraham Lincoln was seen as an equivocating, mediocre president.

To achieve the ultimate level of skill in any profession—particularly the profession of leadership—means accepting a level of incompetence. It also means continually raising the bar and learning the next task while maintaining a sense of poise, grace, and good humor.

Learn to Love the Plateau

I once had an opportunity to spend some time with a writer and martial arts expert named George Leonard, and I was impressed by many of his ideas. Leonard, who has studied the topic of mastery, argues that a basic ingredient in the process involves a willingness to live in that most dreaded of all places—the plateau, the level place in the learning process.1

Our culture places tremendous emphasis on instant gratification, quick fixes, and sound bites. We are busy people, and we do not have time for things that take time. In fact, there is no higher compliment than being called a “quick study.” I actually saw an infomercial for a videotape called Become a Zen Master in Thirty Minutes. Presumably, for $29.95 and a half hour of your time, you can compete with the Dalai Lama for enlightenment!

In this culture of ever-increasing clock speed, if events do not move quickly, we are easily convinced that something is seriously wrong. What’s taking this plant so long to grow? Let’s pull it up and see what the problem is.

The truth is that some things do not happen overnight. Yes, there can be spurts of learning, but they often occur after extended periods of practice in that flat place, the plateau. Whether you are learning a martial art or learning to be a leader, you need to develop the patience to stay in that frustrating place when there are no immediate signs of progress.

Now, there are many ways of being on the plateau. You can kick back and coast. You can tune out and pretend it does not exist. Or you can embrace the plateau with the same focus, energy, and passion that you would if you were getting the instant reinforcement and affirmation that we all love.

I believe that the journey of learning to lead means accepting the reality that leadership skills are developed through long periods of striving with only moderate signs of progress. This means that learning to love the plateau is an essential part of learning to lead at The Edge.

Come to Terms with Fear

Although most people don’t like to talk about it, fear seems to be an integral part of life. Every leader that I have been close to—close enough that they would really level with me—has described times that fear has loomed large in his or her life. Dealing with uncertainty, managing ambiguity, and not always knowing what to do come with the territory of being a leader.

In fact, nature has programmed us to be afraid of perceived threats, and this physiological mechanism has an important function: It helps us avoid danger. Biologists have identified a part of the brain called the amygdala whose function is just that—producing the reaction of being afraid.

Thanks to many years of biogenetic programming, we are quite skilled at being afraid. The problem is that to make a difference in the world, you often have to enter into territory where things can go wrong. Where there is risk, you can fail. You can be embarrassed. Sometimes there are more severe consequences: People can lose jobs, and sometimes, people can even die. There are many circumstances or events that trigger fear.

If fear is that much a part of life at The Edge—if it is that important a part of being human—we ought to know something about it. We ought to make a friend of it, as Joe Hyams suggests in his book Zen in the Martial Arts.2 Making a friend of fear means understanding what is most personally intimidating to us and embracing it rather than pulling back.

The things that provoke fear are different for each of us. Some people are afraid to stand up in front of a group of people to deliver a speech. Others are afraid to take a personal financial risk or deal with the unknown. As Virginia Satir, the well-known family therapist, once remarked, “Most people prefer the certainty of misery to the misery of uncertainty.”

Making a friend of fear means, first of all, understanding what it is that scares you. Second, it means understanding your personal reaction to fear. For example, when you are fearful:

![]() How does your body respond?

How does your body respond?

![]() What do you say to yourself?

What do you say to yourself?

![]() How do you feel?

How do you feel?

You might be like Roberto Goizueta, the former CEO of Coca-Cola, who was asked whether he slept well at night, given all the competition in his industry. “Yes, I sleep like a baby,” he replied. “I wake up every two hours and cry.”3

Finally, making a friend of fear means developing a way to detoxify the fear so that you can maximize your own effectiveness. For example:

![]() You can write about it.

You can write about it.

![]() You can talk to other people about it.

You can talk to other people about it.

![]() You can think about ways in which you have successfully dealt with fear in the past.

You can think about ways in which you have successfully dealt with fear in the past.

![]() You can ask friends for suggestions.

You can ask friends for suggestions.

![]() You can do something else so terrifying that you forget about what you were afraid of in the first place.

You can do something else so terrifying that you forget about what you were afraid of in the first place.

A final observation on fear: Sometimes fear is an obstacle that prevents us from accomplishing something. We say to ourselves, “I can’t do that, I’m afraid.” However, I learned in Vietnam just how much people are capable of achieving while being really scared.

Experiencing fear, therefore, does not mean that you cannot accomplish something. It doesn’t even mean that something is wrong. In many circumstances you are supposed to be afraid. It just means that while you are doing it, you are going to be afraid—perhaps even terrified. The more you accept and engage your fears, the less they will stand in the way.

Find an Environment That Supports Learning

If you want to develop the ability to lead at The Edge, then find an organization that promotes good leadership. Robert Scott learned to be a leader at Dartmouth, where he received the best education the Royal Navy could provide. He later honed his skills by observing naval leaders firsthand, drawing his own conclusions about what it meant to be a leader.

As I have noted earlier, however, the Royal Navy of the time was a flawed institution, still basking in the glow of Horatio Nelson’s past victories. Only such a navy would be content with muzzle-loading weapons while others had adopted the cutting-edge technology of breech-loaded guns. A complacent organization will produce complacent leaders.

The Royal Navy of the 1880s is ancient history, but what strikes closer to home are modern examples of complacency and inadequate leadership. David Nadler, in his provocative book Champions of Change, recounts the eighteen months during 1992 and 1993 in which the CEOs of more than a dozen companies were forced to leave their jobs. Some of the most respected CEOs in the country were forced out of their jobs at IBM, General Motors, American Express, Eastman Kodak, Eli Lilly, AlliedSignal, Westinghouse, Digital Equipment Company, and Compaq. Nadler argues persuasively that the common denominator was that each was an industry leader with a sustained record of success. Each CEO was a victim of the “success syndrome.”4

The characteristics of the success syndrome are eerily reminiscent of the old Royal Navy:

![]() Codification. Informal policies once successful become rigid policies.

Codification. Informal policies once successful become rigid policies.

![]() Internal Focus. Threats from outside forces, such as competitors, are ignored.

Internal Focus. Threats from outside forces, such as competitors, are ignored.

![]() Arrogance and Complacency. Competitive problems are viewed as “only temporary.”

Arrogance and Complacency. Competitive problems are viewed as “only temporary.”

![]() Complexity. Internal politics and the preservation of power become primary objectives.

Complexity. Internal politics and the preservation of power become primary objectives.

![]() Conservatism. The culture becomes risk-averse.

Conservatism. The culture becomes risk-averse.

![]() Disabled Learning. New insights are not incorporated into the organizational memory.

Disabled Learning. New insights are not incorporated into the organizational memory.

As history demonstrates, the presence of these factors can have dire consequences for the organization. These characteristics also have direct implications for leadership. “Junior officers” model their successful seniors; and they behave in ways that are reinforced by the dominant culture of the organization.

The essential point is this: If you want to realize your full potential as a leader, look at the culture of the organization where you work. If it fits the characteristics of the success syndrome, find another. In the right environment, you are much more likely to become an Ernest Shackleton—not a Robert Scott.

Practice the Art of Thriving

Chapter 4 dealt with the vital importance of maintaining one’s stamina as a leader at The Edge. There is, however, a more expansive way of thinking about taking care of yourself. I refer to this broader perspective as “the art of thriving.”

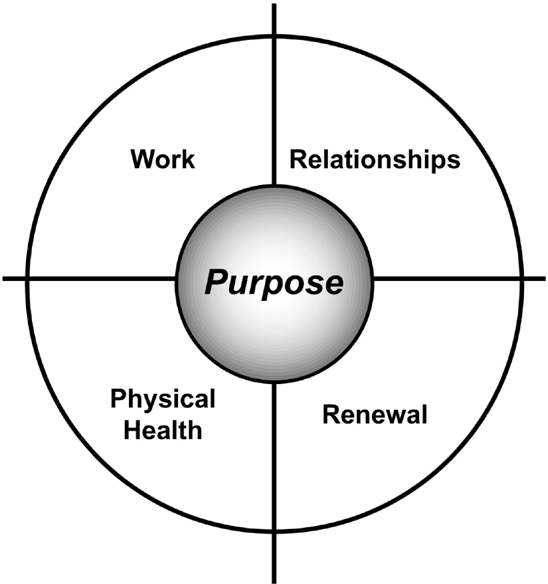

The art of thriving focuses on sustaining career achievement and personal well-being throughout the life cycle. I believe that people who do this successfully are able to integrate the five components of the life structure shown in Figure 11-1.

Each individual has a unique set of needs. The ability to develop a sense of mastery in each of these five areas—work, relationships, physical health, renewal, and sense of purpose—while also establishing a balance among them is essential to personal vitality and thriving.

Work

It is interesting to look at work from the perspective of those who experience it with a sense of passion and excitement. In talking about performing his music, Isaac Stern remarked that playing the violin is not just a “job” but a way of life. “It’s a way of speaking, a way of expressing something … this ecstatic moment when you are at one with the phenomenon of man’s creativity. That’s very special. That’s what is meant by being a musician.”5

Figure 11-1. The “art of thriving” life structure.

You don’t have to be a violinist to experience work as creative expression. On the contrary, I think it can happen in any profession, from computer technology to investment banking. The critical task is to make sure that your unique strengths are brought to bear on a task that provides satisfaction and meaning. In testing the extent to which work contributes to a sense of vitality in your life, here are some questions you might want to ask yourself:

![]() Are you using your unique strengths and distinctive abilities in your work?

Are you using your unique strengths and distinctive abilities in your work?

![]() Are you enjoying what you are doing? Are you having any fun?

Are you enjoying what you are doing? Are you having any fun?

![]() Are you intrinsically interested in the work you are doing? Do you find the substance of the work engaging?

Are you intrinsically interested in the work you are doing? Do you find the substance of the work engaging?

![]() Is your work a creative expression of who you are?

Is your work a creative expression of who you are?

If the answers to these questions are generally yes, then you—like Isaac Stern—are fortunate. If the answers are generally no, however, it is time to rethink this part of your life. The problem might lie with the work itself, or it may be a systems problem, originating somewhere else in the life structure.

Relationships

The importance of supportive social relationships in managing stress and promoting individual well-being has been demonstrated repeatedly. Having others to whom you can turn provides a “psychic balm” that heals many wounds. For high achievers, however, establishing such relationships can be a problem. Life in the fast track leaves little time for developing the kind of mutual relationships that give the greatest support.

This is especially true during times of transition—such as when you are moving, joining a new organization, or starting a new job. During these periods of change, previous social support systems are often uprooted. To make matters worse, the challenges of a new environment and the attendant anxieties about “measuring up” may make it seem as if there is no time for socializing.

Taking the time to develop relationships is more important than ever in times of transition, but you will need to give the relationships in your life special attention. Some questions you might want to ask yourself periodically are:

![]() Where are your sources of support and nurturance?

Where are your sources of support and nurturance?

![]() Who are the people in your life who care about you as a person, rather than simply as a representation of a job title?

Who are the people in your life who care about you as a person, rather than simply as a representation of a job title?

![]() Do you have a sense of belonging in some group or community other than work?

Do you have a sense of belonging in some group or community other than work?

![]() Are you making time to nurture the relationships that are important in your life?

Are you making time to nurture the relationships that are important in your life?

Physical Health

The Spartans had an expression: “You cannot have a healthy mind without a healthy body.” Physical health contributes to good decision making, and many successful leaders I have studied point to sheer energy as an important contributor to their achievement. Unfortunately, the importance of having a sound physical foundation is overlooked when things get hot. Basic needs such as sleep, food, and regular exercise are worth tracking. Some questions to ask:

![]() Are you getting enough sleep, and are you resting well when you fall asleep?

Are you getting enough sleep, and are you resting well when you fall asleep?

![]() Are you eating a balanced diet? Are you using caffeine as a substitute for sleep or exercise?

Are you eating a balanced diet? Are you using caffeine as a substitute for sleep or exercise?

![]() Are you getting enough exercise? Regular exercise is a proven stamina builder. It doesn’t mean you need to participate in a triathlon. Just walking briskly three times a week makes a major contribution, and walking can be done without equipment while you are on the road. The critical point, especially while traveling, is to plan your exercise in advance and to think of it as an important part of your job.

Are you getting enough exercise? Regular exercise is a proven stamina builder. It doesn’t mean you need to participate in a triathlon. Just walking briskly three times a week makes a major contribution, and walking can be done without equipment while you are on the road. The critical point, especially while traveling, is to plan your exercise in advance and to think of it as an important part of your job.

![]() Are you setting aside time—at least fifteen minutes a day—for concentrated relaxation and decompression?

Are you setting aside time—at least fifteen minutes a day—for concentrated relaxation and decompression?

Renewal

Some people attend to all the factors previously mentioned and still experience a sense of burnout and ennui. This problem often originates from a failure to create space for what I call “renewal”—the uniquely personal activities that bring a sense of revitalization into your life. Here are some questions about renewal to examine:

![]() Is there space in your life for you to engage in regenerative activities?

Is there space in your life for you to engage in regenerative activities?

![]() Are there times when you can forget the needs of others and lose yourself in nonwork activities that are absorbing and renewing?

Are there times when you can forget the needs of others and lose yourself in nonwork activities that are absorbing and renewing?

Sense of Purpose

The fifth element in the art of thriving involves the ability to find a deeper sense of meaning in life. This sense of purpose is ultimately grounded in an underlying set of values about what is important, right, or worthwhile. For some people, this purpose has a spiritual basis. For others, it is connected to beliefs about the importance of scientific progress, technological advances, or creating knowledge. For still others, a sense of purpose is rooted in the need to contribute to humanity or to give to others. Once again, I return to Isaac Stern as an example. He said: “I’ve been playing concerts since I was fifteen. The world has been very nice to me, and I’ve taken a lot of things. I have to give something back.”6

Whatever the source, an ability to find meaning and purpose is an extremely important determinant of “stress hardiness” and longevity. Keeping track of the way you are feeling about these deeper issues is important. Lacking this underlying sense of direction, it is extremely difficult to maintain peak performance and personal effectiveness. Spend some time reflecting on the following questions:

![]() How do you feel about the direction your life is taking?

How do you feel about the direction your life is taking?

![]() What are the deeper values that guide your work?

What are the deeper values that guide your work?

![]() Are the other parts of your life—work, relationships, physical health, and renewal—consistent with this sense of purpose?

Are the other parts of your life—work, relationships, physical health, and renewal—consistent with this sense of purpose?

Balance

The final skill in the art of thriving is the ability to find balance among all five elements. Of course, no one can create and maintain perfect balance in life. Personal and professional growth involves change, experimentation, risk, and mistakes. The art of thriving is not based on an artificial attempt to establish rigid equanimity. On the contrary, its essence lies in the ability to know when life is out of balance and when you need to restore balance.

Developing this ability is a lifelong process. Morihei Ueshiba, the famous martial arts teacher, was once asked by a student, “Master, how is it that you are never off balance when you are attacked?” His reply serves as a metaphor: “I am often off center—but I recover so quickly you never notice.”

Mastering the art of thriving, then, means having the courage to explore the unknown, the willingness to risk losing your balance, and the tenacity to find that balance again. It is a demanding journey, but the rewards are great.

Relax … It Takes Time to Play Like Yourself

A final observation on leading at The Edge comes from my ongoing quest to play the tenor saxophone. On this journey I have spent a great deal of time on the plateau—perhaps even at “base camp”—but have yet to be discouraged. One reason for my perseverance is the encouragement of my teacher, Steve, a superb player who brings out the best in everyone.

I always tape my lessons so that I can hear what Steve does, and also so that I can listen to myself and learn what I need to do to perform better. I usually have to grit my teeth when I listen to my own playing, but one day I went to a section of the tape where I had been improvising over a song called “Blue Bossa.” I was amazed. I was incredible. I was fluid. I was creative. I was almost flawless. Then the tape continued and I heard my own voice asking a question. Wow, I was so great I could talk and play the tenor saxophone at the same time.

Then it hit me: I had actually been listening to Steve. It was deflating, to be sure, but I recovered. At my next lesson, I said, “Steve, I’m very discouraged. Am I ever going to be able to improvise like that?” He took out his pencil and wrote out one word on my music: T-I-M-E.

Learning takes time. Once you understand that, you realize that the process of becoming a leader, or a musician, has to unfold. Yes, you need to practice. Yes, you need to work hard. Yes, there are tricks and techniques. But the uniqueness of your personal style has its own timetable. As the great trumpet player Miles Davis once said, “I can always tell when someone is trying to copy me or another musician. Sometimes you have to play for a long time before you can play like yourself.”