CHAPTER 1

Debunking the Myth

New Customers Will Not Save Your Business

In November 2011, Rachel Brown’s bakery, Need a Cake, received the kind of attention many people dream of but never expect to actually get. Feature stories were written about her in The Telegraph and on the Huffington Post, MSNBC, and BBC websites, among others. It was the kind of publicity that would, in almost all cases, be unattainable for a small shop like hers.

After twenty-five years in business, Brown was in the news because her small bakery had done something phenomenal. She had enticed more than 8,500 new customers to her shop in the blink of an eye. But before I share the details about what happened and how Brown got this influx of new customers, I want to ask you a very simple question: Is it really a good thing for a business, of any size, to get 8,500 new customers practically overnight?

Before you answer, let me ask another question: When you hear Brown’s story, are you thinking about the amount of additional revenue your business could receive if you were able to attract 8,500 new customers? Are you envisioning those empty parts of the day when you find yourself wondering whether anyone might actually walk through the door? If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone. Most people—especially small-business owners—think just that. Of course, larger organizations can learn from this story, too, which is my intent.

In this chapter, I’m going to take on the myth that new customers will save your business. It’s a myth that businesses, both large and small, believe wholeheartedly. On the pages that follow, I will demonstrate that new customers are, in fact, a mixed blessing and, further, that putting all your energy into the pursuit of new customers can actually destroy your business. I’m not saying that new customers are inherently bad. Of course not. Obviously, every business needs new customers to grow and thrive. But in almost every case in every company, focusing on getting them takes a tremendous amount of time, effort, energy, and money away from areas where it would be much better spent—like developing deeper relationships with your existing customer base.

The theme of this chapter is simple. If you had the choice, would you want to bring in 100 new customers and watch 50 (or even more) of them run away, never to return again? Or would you rather make a few simple changes to ensure you are consistently strengthening your business relationships with your existing customer base, while also putting new structures in place to make your business entirely Evergreen, where new customers can both flourish and grow with your organization, bringing long-term and perpetual profits? The choice should be obvious.

THE ALLURE OF NEW BUSINESS CAN BE FATAL

Let’s get back to Rachel Brown and her gourmet cake shop, which she owned and operated in Reading, England. Business was good, but business can always be better. She’d heard of this new website called Groupon, where she could offer potential “new customers” a discount to try her service. Groupon offered her a flood of new business—and the company certainly lived up to its promise.1

If you are not familiar with Groupon, here’s how it works: A company will offer a significant discount off its products or services—sometimes as high as 75 percent. Customers then purchase the discounted coupon (called a Groupon). The customer wins by scoring a great discount at a local business. Groupon wins by taking its cut (a percentage of what’s left after the discount—usually another 50 percent). Finally, the business “wins” by attracting new customers. (In reality, though, the business is paid whatever is left over, plus credit card processing fees. In other words, for every $100 Groupon, the business might receive fewer than $25 after all is said and done.)

Brown’s promotion worked—a little too well. She was swamped. In fact, she suddenly found herself inundated with more than 8,500 new customers! She had to hire emergency staff to handle the orders that were coming in, but they had barely a fraction of the training and experience of her regular employees. All of this led to a drop in the quality of her product and the quality of her service. Those new customers likely didn’t walk away from the experience telling their friends about the best red velvet cupcake they’d ever eaten at Need a Cake. Instead, they probably said something like, “I stood in line for so long to get this!”

Many fatal business mistakes can be traced directly back to a company’s focus on acquiring new customers, its lack of appreciation of existing customers, or its lack of understanding customers’ wants and needs. Unfortunately, in Brown’s case, the misstep wiped out nearly a year’s worth of profits and left her deeply regretting her decision. Brown later said, “Without a doubt, it was the worst business decision I ever made.”2

To be fair to Brown, her worst business decision ever wasn’t entirely her fault. The horror stories of companies, especially small ones, side-swiped by the allure of new customers are all too common. Groupon, for example, can be an absolutely wonderful customer acquisition tool for many businesses. But for all the brilliance and effectiveness Groupon brings to getting new customers through its clients’ doors, it is monumentally bad at helping those businesses keep their new customers—an area where I believe Groupon has dramatically underserved its client base.3

WE’RE ALL ADDICTED TO SEX—AND WHAT THAT MEANS FOR YOUR BUSINESS

To understand what really went wrong with Brown’s business, we need to first understand, on a deeper level, why businesses are so focused on getting customers and not on keeping customers. It’s easy to understand the draw for a small business. As the late management guru Peter Drucker often said, “Without customers, there is no business.” Customers are the lifeblood of any business, and for a small business the allure of the new customer is sometimes too great.

Let me share with you a story about an experience I had with my own bank. I had applied for a commercial line of credit for my consulting company and was promised everything would be completed within forty-eight hours. Nearly two months later, my line of credit was finally completed. When I asked the manager why it took so long, he said flat out, “Honestly, Noah, we’re so busy with new customers that we don’t have the time and resources to devote to our existing customers.” Before you scream and pull your hair out, recognize that the manager simply told me what many organizations, including perhaps your own, are going through at this very moment. The reason: We’re all addicted to sex.

Let me explain. In 2012, I presented the closing keynote address to more than 400 publishing executives at their annual conference in Washington, D.C. I began the lunchtime talk with a slide that read, “We’re all addicted to sex!” The clanging of knives and forks went silent as I watched people scramble to find their notebooks, open their laptops, or clean up the water they had just spilled on themselves.

I didn’t plan to start this way, but I had just spent three days sitting in on various sessions at the conference and listening to other speakers. Three out of every four presentations were focused on split testing different text colors and fonts in e-mails (HTML or plain text, size 12 or 14 headlines) as well as optimal sending times (Tuesdays or Wednesdays) and other assorted minutiae of marketing campaigns. The companies presenting this data had certainly done some innovative and creative testing, but it was extremely worrisome to me to see how many businesses, large and small, online and off-line, were more enamored with trying to determine whether it was better to send an e-mail at 9:30 a.m. or 10:26 a.m. than they were with ensuring that the e-mail had something interesting or relevant to say.

The Thrill of the Chase

In the marketing world, retention is boring and optimization (especially around acquiring new customers) is sexy. It feels great, and you get practically immediate feedback on how good your marketing is and if it’s working—very similar to, well, sex. When a large organization steps up to the plate and spends big bucks to run something like a Super Bowl advertisement, it’s pretty simple to measure results almost immediately after the campaign runs. Websites crash, customers tweet, fans like the Facebook page, and sales increase. It often provides instant gratification, and it feels good—again, very similar to, well, sex.

No question about it, the ability to stimulate immediate sales is sexy. But I’m not convinced it is doing us any good in the long run—especially when those same organizations aren’t focused on keeping the customers they just spent Fort Knox to get. I work diligently with all my clients to keep them from getting so wrapped up in their sex addiction that they forget to love their customers. Immediate marketing results—like impressions, conversions, traffic, sales, e-mail open rates, and new subscribers—is all really attractive stuff. The thrill of the chase. The satisfaction of the successful seduction. I get it. But it’s got nothing on long-term customer retention, which is more analogous to love. Love involves having a relationship with your customers, it survives long past the initial glitz and glamour of that first encounter, and it’s ultimately far more fulfilling for both parties.

The Power of an Alternate Mindset

There’s an old analogy in the business world—the Leaky Bucket Theory. This analogy suggests that most businesses operate like a leaky bucket. The idea is that your business is the bucket and the water in your bucket represents your customers. The holes in the bucket are the various areas where you lose your customers. Most businesses tend to focus on adding more water instead of simply fixing the holes. But I digress. We don’t have leaky buckets. We have deciduous trees. Deciduous companies like to invest heavily in marketing, and, more often than not, their marketing works.

My bank was busy. Banks have no problem putting new leaves on the tree. They are swamped with new customers, but like those on a deciduous tree, these leaves stayed temporarily, because as soon as banks close the deal, they move on to bigger and better things—the “more exciting” new customers. My bank was willing to lose me, a loyal, longtime customer with a considerable amount of future value to the organization, because it was too busy focusing on new customers. Instead of banking on an asset, it was gambling with its reserves—no pun intended. Many organizations don’t realize that this mindset is costing them millions and millions of dollars. They fail to recognize the true costs of a new customer focus, such as the additional time, effort, energy, and money required to persuade these customers to buy from them in the first place, and the opportunity costs associated with trying to appeal to these new customers.

My client experience has demonstrated that when an organization can truly understand, and integrate, the relationship between its profit, growth, longevity, customer relationships, employee empowerment, and customer service, then real, impactful, tectonic shifts are generated on its financial statements. This is also the single best way to ensure a business can become Evergreen. Let me say that again:

If you want to experience dramatic growth within your organization, you must truly understand the relationship between profit, growth, longevity, customer relationships, employee empowerment, and customer service.

The cost of ongoing customer engagement is nothing compared with the cost of acquiring new customers.

THE LATEST BOARDROOM BUZZWORD: CUSTOMER-CENTRICITY

I’m sure you’ve heard about the concepts of “customer-centricity” and “big data,” especially if you work in a large organization or read the business section of The New York Times. The problem is that most people use these terms without truly understanding them. I’m bothered by the many organizations that claim to be customer-centric on paper but haven’t internalized the concepts or truly put customer-focused initiatives into action. I can’t state it much better than management consultant and author Jay Galbraith, who wrote that a majority of companies claim to be customer-centric with nothing more than a “cosmetic gloss of customer focus sprinkled around the edges.”4 My goal as a consultant is to help companies go beyond a cosmetic gloss. I’m more interested in your organization getting a permanent tattoo of customer focus. When you are tattooed with a message, you’ve internalized it and there’s no turning back.

What Does It Mean to Be Customer-Centric?

The term customer-centric has been getting a lot of attention lately in the business world, though, as with many business buzzwords, everybody seems to have his or her own definition. In a 2010 article in the Harvard Business Review, Harvard professor Ranjay Gulati defines it as “looking at an enterprise from the outside-in rather than the inside-out—that is, through the lens of the customer rather than the producer.”5

Wharton professor Peter Fader uses this definition: Customer-centricity is “a strategy that aligns a company’s development and delivery of its products and services with the current and future needs of a select set of customers in order to maximize their long-term financial value to the firm.”6

Actually, the ideas behind customer-centricity go back a long time. More than fifty years ago, Peter Drucker was talking about customer-centricity when he made statements like, “A company’s primary responsibility is to serve its customers. Profit is not the primary goal, but rather an essential condition for the company’s continued existence. There is only one valid definition of business purpose: to create a customer.”7

You’ll find Drucker’s books inside almost any executive’s office. Have those executives simply failed to grasp the true meaning of his words? Or is the constant pursuit of new customers with disregard to existing customers a simpler, more exciting ambition for companies? As customer-centricity takes a prominent seat in boardrooms everywhere, I believe we need to get clear on this.

What Will a Customer-Centric Mindset Do for Your Business?

We are living in a new era of how business is conducted. In fact, this is a profoundly revolutionary time to be operating a business. Our customers are more knowledgeable than ever before. Not only that, they have gained the upper hand in their ability to exert, expect, and demand the way they’ll do business and with whom. For an organization to survive it needs to think about its customers and their experiences in an entirely new way. So what’s next?

We need to dig a deeper hole for our Evergreens—to ensure our root systems have the room they need to spread and grow. That’s what’s next. This is why the concept of customer-centricity is so important. In Fader’s definition, customer-centricity is really about customer selection—identifying the most profitable group of customers and focusing attention and resources on them to encourage greater participation, retention, and ultimately profitability. Today, we know more about our customers than ever before. But knowing more or using fancy phrases at our strategy sessions means nothing if we’re not able to use that knowledge wisely.

You’ve probably all heard of the 80/20 rule, also known as the Pareto principle. It states that for many events, roughly 80 percent of the effects come from 20 percent of the causes. In my consulting work, I’ve found that the 80/20 rule remains true in almost every business, of every size, regardless of industry. The top 20 percent of customers generate 80 percent of profits. Our mistake, however, is that we are not spending enough time or resources on the top 20 percent. Remember, just having access to a lot of data and claiming to be customer-centric doesn’t mean you are truly focused on what’s best for the customer.

THE TRUE VALUE OF A CUSTOMER

What’s a customer really worth? Now, this is a tough question—one that many organizations struggle to answer properly, but it is certainly an important one to discuss. Later in the book I’ll bring you back to planet earth and make a few commonsense, on-the-ground suggestions, but for now, let’s explore how most larger organizations determine the value of a customer and expose a number of misconceptions tied to the way it’s currently done.

Understanding the Limitations of the Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) Model

Most organizations focus on measuring customer lifetime value, sometimes referred to as average customer lifetime value. CLV is often seen as the Holy Grail of data analysis. It’s an idea that’s seductively simple and makes great intuitive sense. It’s the reason credit card companies will spend a tremendous amount of money to acquire new customers. They know, with some certainty, what the average customer is worth to them. There are, however, a number of drawbacks to basing a customer’s worth on the CLV model.

One major issue has to do with the idea of averages. The reason that keeping customers can be difficult for companies is directly due, in large part, to their practice of viewing their customer base as this single, amorphous blob that can be understood with simple averages: “Our average customer is 37.34 years old, has 1.38 children, a salary of $53,332, and lives in a city of 100,000 people or more. This customer is expected to spend $237.12 with us this year, but let’s see if we can get a little bit more with some clever social media marketing!” I’m oversimplifying and dramatizing here, of course, but in looking at the bulk of communications between companies and their customers, can there be any doubt that most companies are far less interested in you as an individual than in you as part of “their customer base”?

Step out of your role as a business-minded professional for a minute and into the role of a consumer, which you are as well. Think about your own interactions with various companies: When was the last time you got an e-mail, an auto-responder, or a canned response? Think about the last time you called a customer support line. More to my point, think about the last time you were treated as “average.” How did that make you feel? I very much doubt you are seeing visions of sugarplums!

Here’s the other major issue with CLV. If you just look at the customer lifetime value, which is an average across an entire customer base, you can’t determine the commonalities among those customers who stopped doing business with you early on, in order to address why they left. Nor can you identify the commonalities among customers who continue doing business with you year after year, in order to encourage new customers to follow the same path. Have you ever tried to do this? If so, does it feel as though you are just throwing darts?

Using CLV Data Creatively

Looking only at a single CLV number clouds a lot of useful information. As an example, consider a small to medium-size business that spends $50,000 per year on each of its two primary channels of new customers: Google Pay-Per-Click (PPC) ads and good old-fashioned referrals. With a firm grasp on the average CLV, this company may believe that as long as it is putting enough leaves on the tree, everything will be just dandy. But it might be the case that only 10 percent of referrals end their relationship with the company within the first forty-five days, while 60 percent of PPC customers quit during the same time frame. Knowing this, the company’s managers might decide to dramatically reduce spending on PPCs and increase spending on referral generation. Of course, they don’t know—because they’re using a single number to make important marketing decisions.

There are ways to make customer lifetime value more useful, including finding multiple CLVs across different segmentations of a customer base. For example:

• What’s the customer lifetime value of males under age 30?

• How about females over age 40?

• What about customers who made their first purchase of greater than $100 within the first week?

• What’s the total CLV of all customers vs. the CLV of customers with more than ten purchases?

• What’s the CLV of customers who used a coupon or took advantage of a sale on their first visit vs. the total CLV?

Once we begin to look at subsets, we enter into the territory of data modeling, which brings us straight to this “big data” thing you keep hearing about. Does your head hurt yet? I know mine does.

Recognizing the Truth About “Big Data”

In a nutshell, here’s the truth about big data: It’s not size that matters; it’s how you use it. Seriously! Organizations have more data than ever before. We know more about our customers than we ever thought possible, and we’re beginning to use that data to make some insightful decisions. Some exceptionally customer-centric organizations are making great strides in this regard, using that data to make a more positive experience for their customers.

Amazon, for example, is one of the most customer-centric companies of our time. Some people would argue it is the most customer-centric company on the planet. Amazon is one of my favorite examples of an Evergreen organization. From early on, it focused with laserlike precision on the customer and the customer’s experience. It continues to push the envelope by learning more about its customers and tailoring the experience to them. I’m sure you’ve shopped on Amazon. What happens is that while you’re looking for products, Amazon’s systems are helping products find you. It can be scary and daunting to realize that Amazon knows more about your shopping habits than your own spouse does.

Personal privacy and creepiness factors of big data collection aside, I love telling the story of how Kmart knew a teenage girl was pregnant before her own father did based on how her purchasing patterns matched the company’s models of the purchases of pregnant women. On the other end of the spectrum, the magic of all this data is that it enables companies to be more responsive in not only meeting but also exceeding their customers’ expectations. It allows organizations to create and tailor ongoing conversations with their customers.

Putting Your Equity Where It Matters

When it comes to the various ways of using big data, it’s easy to fall down the rabbit hole. Of course, I fully expect large organizations to continue to improve upon their usage of CLV calculations, but for the sake of this book, I’d like to make a few simpler suggestions.8 Your customer base is the single most valuable asset your business has. Not your employees. Not your products or services. Your customers. As noted earlier in the Peter Drucker quote, “Without customers, there is no business.”

The value of that asset is determined by a number of things, but primarily it is based on the equity you build into the customer relationship and the future value you can derive from that asset. It doesn’t get simpler than that. Big data is important—but only if we use it to support our customers’ needs. We need to start making smart decisions about our investments. When we view everything as an “average,” we often make important business decisions based on only half-good information.

If you were a real estate investor, for example, you wouldn’t buy a dumpy home in a dumpy neighborhood with little future potential. You would look for an investment property with decent current value and lots of potential value. On the other hand, you might look for something with a low current value but the potential for a big future payoff. Just like investing in the stock market, a smart, balanced investment portfolio contains a mix of low-risk investments alongside riskier investments. But why do companies insist on investing almost everything on new customers? These investments have no history. This is seriously risky business. Our customers are not all created equal. Do you believe your marketing dollars are generating their maximum return when you invest equally in all your customers? No.

It quickly becomes obvious that knowing how to use the data to increase the value of a customer, or a group of customers, is much more important than simply acquiring piles and piles of data. Furthermore, if we really want to increase the value of our customers through the use of our data, then the most important kind of data we can collect is behavioral. When a school of fish swims together, all the fish face in the same direction. If a single fish turns, for whatever reason—it might see the shadow of a wading fly fisherman or catch the scent of a tasty morsel, for instance—the other fish often turn as well. They act in unison. Customers act in a similar fashion.

Applying These Concepts to Your Business

Whenever I work with online entities like subscription and paywall sites, I typically show them how to precisely monitor, measure, and track consumption, usage, and participation data of their customers, and how to sort those customers into groups based on their likelihood of future profitability, with each group requiring its own marketing, contact, and communication plans to ensure they receive the most value from the company. Make sense? Any business can apply these techniques, including yours. Just remember: Your primary goal must be to make wise decisions about where to invest your dollars with the highest potential for future value.

As we’ve compiled massive amounts of data, we are in a much stronger position than we’ve been in the past, which means we are less dependent on guessing. There’s a good chance you have an incredibly talented team of marketers and engineers sifting through your customer data. And if you don’t, I’ll show you how small, family-owned businesses have used these concepts on a small scale with massive impact. The rest is really about using a commonsense approach to tie it all together. When you do that, you can make wise decisions about the path your customer travels when conducting business with your organization, and you strengthen both the relationship and conversation between customer and company, never letting that customer stray too far off the path.

Further on in the book, I’ll demonstrate how easy it is to set up Mission: Impossible–style alarms that let the appropriate management or customer care staff know when your customers’ usage patterns indicate that there is a high risk of losing them, and know how to enable personalized contact (or, alternatively, how to set up systems that recognize these patterns and automatically take the appropriate action). Remember that school of fish—when one fish turns, they all turn. I’ll show you how to recognize when this might be happening, and what you can do to stop it.

INTRODUCING THE EVERGREEN MARKETING EQUILIBRIUM

A few years ago, I met with a client whose marketing team was solely focused on “getting” more new customers, while paying almost zero attention to “keeping” existing customers. This client didn’t have a leaky bucket; he had a bottomless bucket! More appropriate to our broader Evergreen analogy, though, his business was like a shriveled-up tree without any leaves and with a rotting root system, yet the gardener insisted that he keep watering it.

This client kept talking about his team’s impressive “sales closing” ratios. Perhaps he had been overly inspired by Alec Baldwin’s classic “Always Be Closing” speech in the film Glengarry Glen Ross. However, I don’t believe you “close” a sale—you “open” a relationship.

The sales transaction is the start of the relationship, not the end. Sales professionals everywhere would instantly become better at what they do if they simply banished the idea of “closing.” This client in particular was leaving millions of dollars on the table by hyperfocusing on the sales closings.

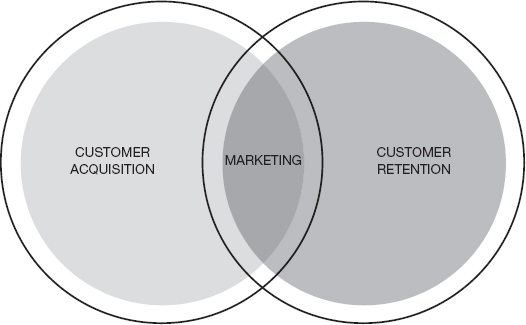

The Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium, shown in Figure 1-1, represents the balance between customer acquisition and customer retention that an Evergreen business must maintain in order to stay healthy. Balance represents stability in your marketing efforts. I created this visual on the spot while talking with my “bottomless bucket” client.

The Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium

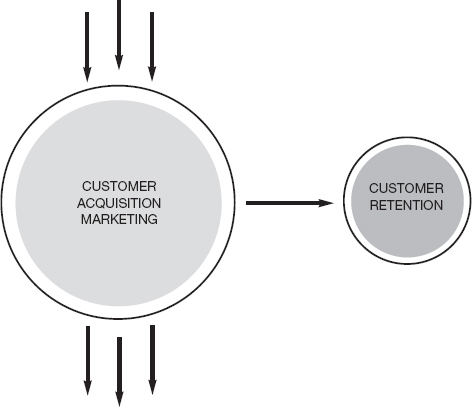

When comparing my client’s operations with the Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium, we concluded that because his customer acquisition and customer retention efforts were two entirely separate processes, the circles weren’t touching. His sole focus was getting new customers, which meant that his marketing efforts were completely out of whack. Figure 1-2 shows what was happening in his operations: He brought in new customers (indicated by the arrows), but most just slipped out the bottom. Through happenstance (and not any deliberate marketing efforts) a few of these customers stayed on, and they moved over to the retention circle. Without proper balance between customer acquisition and customer retention, it’s difficult to market your business effectively. In this situation, gravity seems to have a stronger pull than any “marketing” that’s being done. Unfortunately, Figure 1-2 depicts the situation many organizations are in.

Unsustainable Marketing Scenario

The Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium is a surprisingly simple concept, but it’s worth asking yourself: How would you diagram your organization’s marketing efforts? Since an equilibrium is the balance of two opposing forces, you obviously want to treat them as one. But as a Customer Retention Guy, I tend to focus on adding even more weight to the right-hand side. A little bit of instability is okay, as long as you are more focused on how you’re going to keep the customers once you have them.

Let’s consider what this all means. If your circles aren’t touching, chances are you have:

• Low marketing effectiveness

• High customer acquisition costs

• High churn

• High stress

If you are able to balance the Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium in your business, you’ll experience:

• Higher marketing effectiveness

• Enhanced customer loyalty

• Lower customer acquisition costs

• Less customer attrition

• Increased profits

• Better understanding of your customers

• More referrals

• Greater word-of-mouth

• More valuable customers

• Greater success

The Evergreen Marketing Equilibrium provokes thought, doesn’t it? It is challenging because it hits home for many organizations. Growth is good. New customers are a necessity. Nobody would argue against that. But most organizations don’t understand the true cost of a narrow-minded focus on acquiring new customers.

When we look even deeper into the true cost of lost time, we find an enormous profit killer. This time would be much better spent deepening relationships with existing customers—and the results would be far more fruitful than any customer acquisition escapades could ever offer. I guarantee it. Focusing solely on acquisition (in hopes that you can stop the leaves from dropping, or so that you can continue to add new leaves, as needed) is a wasteful, myopic, and arrogant business strategy—one that is followed and embraced all too often.

This is really the essence of Evergreen. I’m talking to companies all the time that are looking for something more. They are looking to improve conversions. They are looking to write better ad copy and create viral videos. They are figuring out the best time of day to send an e-mail or post to their blog. They’re collecting more data. And all this is happening while their current customers continue to drop like dead leaves.

It doesn’t have to be that way.