INVESTING IN YOUR HOME

Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.

—MARK TWAIN

Bill grew up in Porterville, a small town in California’s great Central Valley. He was valedictorian of his high school class of twelve students. Bette grew up in Indio, a small California desert town that was perhaps best known for its annual date festival, which features camel races and a surprising variety of foods made with dates—including date ice cream.

Bill and Bette married in 1942 and bought their first home in 1946: a 900-square-foot, two-bedroom home, 100 yards from a railroad track in a modest suburban community that was close to Bill’s job in Southern California’s aerospace industry. They paid $4,000 for this home with a $500 down payment and a $3,500 mortgage.

By 1954, they had four children, the oldest age nine, a three-year-old, a one-year-old, and a newborn. They needed a bigger home and Bill’s growing salary allowed them to afford one. They bought a three-bedroom, two-bath tract home in La Habra, another quiet Southern California town. They sold their first home for $8,000 and paid $13,000 for their new home.

They raised their family in this home until their children were grown and Bill and Bette had grown tired of how crowded and congested Southern California had become—not at all like their childhoods in Porterville and Indio. In 1990, Bill retired and they sold their La Habra home and bought a condominium on Golf Course Road in Thatcher, Arizona. Bill taught at the local community college and played golf almost every day; Bette took photography classes at the community college and took pictures of Arizona’s natural beauty.

Bill’s pension from his aerospace employer, his Social Security payments, and the money they netted from selling their La Habra home and buying a home in Thatcher provided them with a secure, comfortable retirement.

Their lifetime of homeownership turned a $500 investment into a comfortable retirement nest egg. In addition, the rent they saved every year for decades paid for college for all four of their children. Their home was the best investment they ever made. I know because they were my parents.

THE INTRINSIC VALUE OF A HOME

The biggest investment that many people will ever make is the house they live in, yet they don’t think of their home as an investment. Homes aren’t like stocks. Homes are just where we happen to live, right? Nope. A home is an investment just like stocks.

Stocks pay dividends. What is the income from a home? A New York Times writer couldn’t figure it out. He said that “houses have no underlying revenue stream (such as a stock’s corporate earnings) on which to base an assumption of true value.” He was completely and utterly wrong. Homes do have income. It’s subtle, but it’s absolutely crucial for understanding how a home can be valued the same way as stocks.

For a landlord, the income is obvious—the monthly rent check from the tenants. If you own your home, there is income, too, but it is harder to see because no one gives you a check each month. The income is the rent you don’t have to pay. If you rent a home for $1,500 a month, this money goes out of your bank account and into your landlord’s account. If you own your home, $1,500 doesn’t leave your bank account. This $1,500 is not theoretical. It is real dollars that you can use for food, clothing, and entertainment. This $1,500 is income from your home.

Home buyers don’t usually think this way. Some homeowners consider their home a “necessary expense,” like food and clothing. They figure their home is worth what other homes are selling for (what are called comps). If a similar house sold for $400,000, that’s what their home is worth. That’s like saying that stocks are a necessary expense and a stock is worth what similar stocks sell for. Value investors know better.

A second, very different type of home buyer thinks real estate is a speculative road to riches. They buy homes to “flip” a short while later for a profit, the way stock traders count on a line of greater fools. They are too quick to assume that however fast home prices have gone up in the past, they will continue doing so in the future. They think they can buy a house for $400,000 and sell it a few months later for $450,000. Money for nothing. Value investors know better.

IF I BOUGHT IT, IT MUST BE WORTH WHAT I PAID

Some financial advisers view residential housing as a foolproof investment that does not require financial analysis. A former managing director at Salomon Brothers argued that “there is no bad time to buy.” A prolific real estate author and professor was only slightly more restrained, stating that “90 to 95 percent of people [who buy a house] will say it is the best investment I ever made.”

Humorist Will Rogers seconded Mark Twain’s argument when he offered this tempting reason for optimism: “Don’t wait to buy land. Buy land and wait, the good Lord ain’t makin’ any more of it.” The same argument could be made about anything with a fixed supply, including many things that would not be taken seriously as investments, including Lisa computers, Chrysler New Yorkers, and last year’s clothing fashions. (If you don’t know what a Lisa computer or Chrysler New Yorker is, that makes my point.)

George and Mary Parker learned this lesson another way. The Parkers live in Naples, Florida, a small city on the southeastern coast of Florida. The Naples beach has been voted the best beach in the United States, and the town itself boasts that it has more golf courses, millionaires, and CEOs per capita than any other city in the country. After the dot-com stock market crash, the Parkers sold their stocks and started investing in real estate by buying small Naples homes in older neighborhoods on the wrong side of the highway—away from the beach.

Home prices in Naples more than doubled between 2001 and 2005 and, along the way, the Parkers made a lot of money flipping homes. They bought their first Naples property in 2001 for $180,000, with a $30,000 down payment and a $150,000 mortgage. They made some cosmetic repairs and sold it nine months later for $210,000. They used the profits to buy two similar homes, which they sold in less than a year. By 2005, they owned thirteen homes, all very much like the first home they bought in 2001. In fact, they bought one home in 2002, sold it in 2003, and bought it back again in 2005 for twice what they had paid in 2002. Sometimes they rented their homes to help make the mortgage payments; other times, they flipped a home before they had time to find a tenant.

The Naples housing market weakened in 2006 and the easy flipping ended. The Parkers’ rental income didn’t cover their mortgage payments and buyers weren’t lining up to buy homes. The Parkers tried to sell one home through a real estate auction, but the highest bid was 30 percent less than the price they had paid. The Parkers refused to accept this bid or to consider the possibility that they had paid too much. George argued that the prices they paid were okay because appraisers valued the homes at close to their purchase prices.

Where did the appraisers’ numbers come from? From comps, of course. The house they bought in 2002 and repurchased in 2005 was appraised at $220,000 in 2002 and at $450,000 in 2005 because that’s what similar houses were selling for in 2002 and 2005. These appraisals didn’t mean that the house was actually worth $220,000 in 2002 and $450,000 in 2005. A Beanie Baby wasn’t worth $500 because some fool paid $500 for it. A dot-com stock wasn’t worth $1,000 because some fool paid $1,000 for it. A Naples rental property wasn’t worth $450,000 because the Parkers paid $450,000 for it. A home isn’t worth $450,000 unless it generates enough income to justify the price. The Parkers’ properties didn’t.

THE HOME DIVIDEND

Peter Lynch, the legendary mutual fund manager, wrote:

Because of leverage, if you buy a $100,000 house for 20 percent down and the value of the house increases by 5 percent a year, you are making a 25 percent return on your down payment.

This fixation with price appreciation is horribly misleading. It is very much like buying a stock because you think the price is going up. That’s what speculators do, but not value investors—either in the stock market or the real estate market. Value investors think about the income from stock and real estate.

Some people recognize that because we have the option of buying or renting, we should compare monthly rent with monthly mortgage payments. For example, in its 2002 housing report, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies estimated that the average renter paid $481 per month while the buyer of the median single-family home paid an $821 monthly mortgage payment. This is another of those apples-and-oranges comparisons that is only superficially relevant. The average rental property may be much smaller than the median home, and in a different place, too. The three most important things in real estate are location, location, location. We need to compare the cost of buying or renting the same property, not the cost of renting a two-bedroom apartment in Detroit with the cost of buying a four-bedroom home in Atlanta.

A 2005 article in Fortune magazine did a better job by using a real example:

[The Olsons] crunched a few numbers. This time they decided to rent—and they’re saving a bundle. For $2,350 a month, they have a four-bedroom, 2,100-square-foot home. If they were to purchase that same home today for $700,000 (the going rate for a similar home in the neighborhood), the monthly payment on a thirty-year, $630,000 mortgage at 6.1 percent would run them more than $3,800.

However, this analysis is flawed too. The monthly mortgage payment depends on the down payment and the length of the mortgage. Suppose, for an extreme example, you pay cash for a house and have no mortgage payments. Is buying therefore guaranteed to be better than renting?

In addition, Fortune neglects the fact that the interest portion of the mortgage payment is tax-deductible and omits property taxes, insurance, and maintenance expenses. It also ignores the fact that rents will probably increase over time, while mortgage payments are constant and then end when the loan is repaid.

Just like stocks, think of a home as a money machine and estimate the cash coming out of the machine. The income that a home generates is the rent a homeowner would otherwise have to pay a landlord. There are expenses, too. Homeowners make mortgage payments and pay property taxes, homeowner’s insurance, and maintenance expenses when a faucet drips and the walls need to be repainted. A home’s net income is the difference between the income and expenses. Because this net income is as real as the dividends from a stock portfolio, I call it the home dividend.

There are surely nonfinancial considerations that make renting and owning different. Renters might not like the pumpkin-orange walls the landlord picked out. Renters don’t get any financial benefit from remodeling a kitchen or landscaping a yard. Renters might have less privacy than homeowners. These are all arguments for why owning is better than renting and, to the extent they matter, why home-dividend calculations underestimate the value of homeownership.

It is not true that you can’t go wrong buying a home. The claim by the former Salomon Brothers director that “there is no bad time to buy” is embarrassingly silly. Everything has a price that is too low and a price that is too high. An apple is a bargain at a penny and too expensive at $100. The question for value investors is whether the home dividend makes the price a bargain or a mistake. It is the same question value investors ask about stocks.

A HOME IN FISHERS, INDIANA

Let’s look at a very specific example. In the summer of 2005, a three-bedroom, three-bathroom, 1,917-square-foot house in Fishers, Indiana, was purchased for $135,000 with a 20 percent down payment ($27,000) and a thirty-year mortgage. Fishers is an attractive Indianapolis suburb. The median family income is over $100,000 and Money magazine ranked Fishers among the top 50 places to live in the United States in 2005, 2006, 2008, 2010, and 2012.

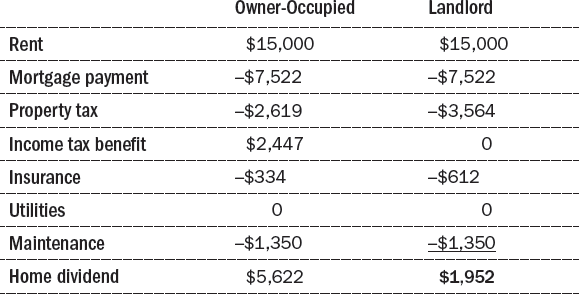

I estimated the home dividend by making a list of the financial benefits and expenses from homeownership—the cash going in and the cash going out. Table 16-1 shows the estimated values for the first year. The details are explained in the Appendix at the end of this chapter.

Rent savings |

$15,000 |

Mortgage payment |

−$7,522 |

Property tax |

−$2,619 |

Tax savings |

$2,447 |

Insurance |

–$334 |

Utilities |

0 |

Maintenance |

–$1,350 |

Home dividend |

$5,622 |

The biggest benefit is the rent saving; the biggest expense is the mortgage payment.

The bottom line is a first-year home dividend of $5,622. After one year, the homeowners will have $5,622 more in their bank account than they would have if they were renting. Just like a stock portfolio that pays a $5,622 dividend, this $5,622 is their home dividend.

Is $5,622 a good return on their investment? As with stocks, we should compare the dividend with the size of the investment. When you buy a home, your investment is the cash you put up for the down payment and closing costs. Here, the down payment is $27,000. We’ll add $3,000 in closing costs to make it an even $30,000 investment. They invested $30,000, which they could otherwise have invested in stocks. The $5,622 first-year home dividend is a 19 percent after-tax rate of return on their investment! Where else could they invest $30,000 and get a $5,622 dividend the first year?

The home dividend will get bigger each year because rents will increase, but the mortgage payments won’t (if it is a fixed-rate mortgage). Let’s assume that rents, property taxes, insurance, and maintenance all grow by 3 percent a year. The home dividend will be $5,942 in the second year, $8,843 in the tenth year, $13,471 in the twentieth year, and $19,478 in the thirtieth year. Then the mortgage payments stop. The home dividend jumps to $27,744 in the thirty-first year and keeps on growing. What a great investment!

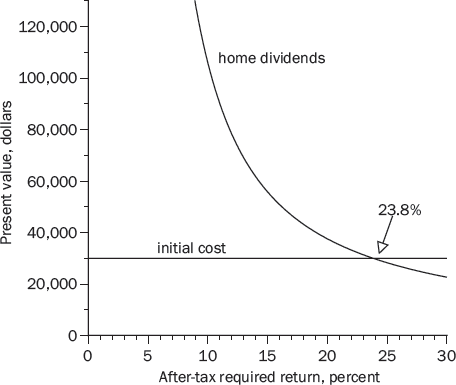

Just like stocks, we can calculate the present value of the home dividends and compare this intrinsic value to the $30,000 cost. Figure 16-1 shows the intrinsic values for after-tax required returns up to 30 percent. The breakeven return is 23.8 percent. This home is an attractive investment for any after-tax required return below 23.8 percent.

For an after-tax required return of, say, 10 percent, the present value of this $30,000 investment is $106,000. This is like buying a stock for $30 a share that is really worth $106. For an after-tax required return of 5 percent, it is like paying $30 for a stock worth $476. These are genuine $100 bills on the sidewalk.

CASH IS KING

When I presented this example at a conference organized by the Brookings Institution, a prominent economics professor said that I was wrong because his sister lives in Indianapolis and home prices there only go up by 2 to 3 percent a year. He missed the point completely. Why is this home in the Fishers suburb such a great investment? Not because I assumed home prices will increase rapidly. I didn’t make any assumptions at all about home prices! Just like the intrinsic value analysis of a stock, I assumed that the home buyer never sells. All the value comes from the income generated by the investment. A home is a money machine just like stocks.

Too many homeowners focus on comps and price appreciation when they should instead be thinking about their home dividend. When you buy a home to live in, you get home dividends equal to your rent savings and tax benefits minus your mortgage payments and other expenses. In the Fishers example, you would have to earn a 23.8 percent after-tax return on a $30,000 stock investment to do as well. Where are you going to find another investment that gives you such a wonderful return? Where are you going to find an investment that gives you as much pleasure as the home you live in?

We can also calculate the future value of your investment if you buy the Fishers home and invest the annual home dividend in a stock portfolio paying a modest 5 percent after-tax return each year. After thirty years, you will have $668,379 and be living in your home rent-free and mortgage-free. After fifty years, you will have $2,948,642.

I haven’t said anything yet about how much home prices increase. Now I will. Table 16-2 shows your total after-tax wealth, invested home dividends plus the value of your home, if home prices increase by zero, 3 percent, or 5 percent a year over the next fifty years.

Even in the case of 5 percent annual price increases, most of the increase in your wealth comes from the home dividends.

Price appreciation can certainly be an added bonus, but it isn’t the most persuasive reason for buying a home. Don’t buy a home because you think the price will be 10 percent higher a year from now. Do buy a home because you plan to live in it for a while and believe that it is cheaper to pay off a mortgage than to pay a landlord.

THE LONG VIEW

Suppose that you live in one area for sixty years. And suppose that you change houses every ten or fifteen years. You marry and divorce. You have children and your children grow up. You change jobs and so on. For whatever reasons, you might own four or five different homes during these sixty or so years. Annual ups and downs in home prices aren’t all that important. If you sell your home for a higher price than you paid for it, you will also pay a high price for your next home. If you sell your home when prices are low, you will also pay a low price for your next home. Over long horizons, the income you get from owning your home—your home dividend—will usually be much more important than zigs and zags in home prices.

Once you focus on years and years of home dividends, a home is not as unpredictable an investment as you might think. While buying a home might seem risky, not buying is risky, too. If you wait too long, you might get priced out of the market and have to pay rent for the rest of your life. Or think of it this way. You need a place to live—which you can pay for with rent or with mortgage payments. Which is riskier: making constant mortgage payments or making rent payments that can change every year?

Some people don’t consider their home to be part of their wealth. They say, “Everyone has to live somewhere.” Yes, everyone has to live somewhere. But you can choose to be a renter or an owner. A home is a place to live, but homeownership is an investment.

Others say, “But I will never sell my home and live in the street, so my home isn’t really valuable like stocks.” You don’t have to sell your stocks for them to be profitable investments. Their value comes from the cash they generate. The same is true of your home. Remember Warren Buffett’s advice: “I never attempt to make money on the stock market. I buy on the assumption that they could close the market the next day and not reopen it for five years.” Think about your home in the same way. Don’t try to predict home prices next week, next year, or five years from now. If it helps, assume that the real estate market closes after you buy your home.

Now you can focus on what really matters—the home dividend. If your mortgage payments (and other expenses) are less than what you would pay in rent, your home is paying you a monthly home dividend. When your mortgage is paid off, you will be living in a home with some relatively low expenses (such as property taxes and maintenance) and saving thousands of dollars in rent. All the money you don’t pay to a landlord is money that you can spend on food, clothing, entertainment, whatever you want. Yes, your home is valuable, like stocks, even if you never sell your home.

RENTAL PROPERTIES

Once you understand that the investment value of a home depends on the home dividend, you also know how to value rental properties. Buy a rental property for the income, not because you think the price will increase rapidly.

We’ve seen that the income from a home comes from the rent savings. If the rent savings are large enough to make a home a profitable investment, then it would seem that buying the home and renting it to someone else will also be a profitable investment. This general idea is correct, but a few details complicate matters.

One detail is that when you buy a home and live in it, you save rent every single month. But if you buy a home and rent it out, you only collect rent if you have tenants. If there is a gap between when one tenant moves out and the next tenant moves in, you lose rent while the home is vacant. You also lose rent if tenants refuse to pay and it takes a while to evict them.

Your maintenance expenses might also increase. If you live in your own home and have a leaky faucet, you can just slip in a new washer. If you are a landlord and the property is not close by, you might have to pay a plumber $75 to slip in a washer. Also, people who own the house they live in are more likely to take good care of it. People living in a stranger’s home are more likely to be careless or destructive. So your maintenance expenses are likely to be larger if you rent a home to someone else than if you live in it yourself. Finally, the tax rules are different for owner-occupied homes than for rental properties.

ADVERSE SELECTION

Adverse selection occurs when high-risk people take advantage of deals intended for low-risk people. For example, if life insurance companies cannot distinguish those in poor health from those in good health, it must offer the same premium to both. Those in poor health are more likely to buy such policies and file claims, and this reduces the insurance company’s profits.

In the real estate market, an adverse-selection problem arises if people choose to rent because they believe they are likely to lose their job, are not handy around the home, are accident prone, or have unruly children and pets. I am not saying that these are universal traits, only that these characteristics might be more prevalent among renters. If they are, landlords might find themselves with tenants who are unemployed klutzes with destructive children and pets.

MORAL HAZARD

There is a moral hazard problem when a person behaves differently if someone else is paying the bills. For example, a person might be less concerned about the cost of medical tests if the insurance company pays for the tests.

In extreme cases, unscrupulous people crash insured automobiles and burn down insured buildings. There’s even a joke that goes like this: Two friends meet each other unexpectedly at a European resort. The first person explains that he bought a warehouse and it burned down; he is using the insurance proceeds to pay for his vacation. The second person responds that he bought a building that was destroyed by a flood and that he, too, is spending the insurance money on a vacation. “Gee,” the first person asks, “how do you start a flood?”

Deliberately causing damage to collect insurance is illegal. But it is not illegal to be less careful. In the real estate market, it seems self-evident that most people will take better care of a home if they own it than if they rent it. Some friends of mine learned this lesson the hard way. They rented out their Vermont home while they spent a year in Scotland with relatives. Their tenants piled mattresses in the front yard so that their children could jump off the roof, roasted marshmallows around a campfire on the living room floor, and ripped a bathroom sink out of the wall and took it with them when they moved out. Would these tenants have done any of these things to their own home?

That story is real. The next is a joke (I hope). Jack lives in New Hampshire and his heating bills have skyrocketed. Seeing all the trees around him, he realizes that he can heat his home by burning logs. One day, he calls his friend Mack to come over and bring an ax and a chain saw. Jack found an old oil drum at the town dump and wants to put it in the basement. The drum won’t fit through the cellar door, so Jack uses the ax to cut some posts and widen the opening. Once the drum is in the basement, the plan is to burn logs in the drum and let the heat rise to warm the house. The next problem is how to get the heat from the basement into the house. No problem. Jack also found an old heating grate at the dump. He walks into the living room, traces an outline of the grate on the wooden floor, and then uses the chain saw to cut a slightly smaller hole that the grate can rest on. He nails the grate in place with two-by-fours. Problem solved. No one will fall through the hole in the floor and the heat from the burning logs will warm the house nicely. Mack admires Jack’s ingenuity, but asks what the insurance company will think of this heating system.

Jack replies, “Insurance? That’s the owner’s problem!”

LONG-DISTANCE LANDLORDS

My wife and I live in Southern California, where home prices make homes in many other parts of the country look like irresistible investments. As in the Fishers example, home prices are so low relative to the home dividend that buying a home to live in has a double-digit after-tax return.

This wasn’t a temporary aberration. We looked at decades of data and found homes to be attractively priced for many years in many parts of the heartland. In the Indianapolis area, homes were a good investment twenty-five years ago and have become an even better investment over time. Rising rents and falling mortgage rates have increased home dividends greatly, while home prices have risen by a leisurely 2.2 percent a year. The average Indianapolis home that we looked at in 2005 cost $14,000 a year to rent but could be bought for only $146,000. People who are going to live in Indianapolis for many years can almost surely look forward to a very rewarding return from buying a home there.

When my wife and I saw these stacks of $100 bills, we looked into becoming long-distance landlords, buying single-family homes in Indianapolis, Atlanta, Dallas, and many other parts of the country and renting them to local residents. But the closer we looked, the less attractive this idea appeared. We would have to research the neighborhoods and fly out to look at the homes before buying them. We would have to pay someone to screen prospective tenants and keep an eye on the houses. We would have to pay someone to do home repairs. (It doesn’t make sense to fly to Indianapolis to replace a washer!) Property management companies will take care of most of the details, but their fees are typically 5 to 10 percent of the rent. We would also need to deal with vacancies, unpaid rent, and damage to the property. The costs just kept piling up.

In addition, the income kept shrinking. If you own your own home, you get lots of tax breaks that landlords do not get. Most important, a landlord’s rent is taxable income, but homeowners don’t pay taxes on the rent they save by living in their own homes. Expenses are also handled differently, and the proverbial bottom line is that the prospective after-tax income is generally much lower when buying a home to rent than when buying the same home to live in.

FISHERS, INDIANA, AGAIN

Let’s look again at the three-bedroom, three-bath house in Fishers, Indiana. Table 16-1 showed that the homeowners’ estimated first-year home dividend was $5,622. Let’s see what the home dividend would be if this home had been rented to someone else for $15,000 a year.

Table 16-3 shows the income and expenses. The details are explained in this chapter’s Appendix. The home dividend is much smaller for a landlord than for someone who buys the house to live in.

The biggest factors that cut into the home dividend are:

1.Many states, including Indiana, levy higher property taxes on rental properties than on owner-occupied homes.

2.Landlords do not receive a tax saving from mortgage interest and property taxes because these must be used (together with depreciation and other expenses) to avoid paying taxes on the rental income. Owner occupiers do not have to give up their tax saving because their rent savings are not considered taxable income. They can consequently use mortgage interest and property taxes to reduce the taxes they pay on their other income.

The landlord numbers in Table 16-3 might be too optimistic. I initially assumed that the maintenance expenses are $1,350, regardless of whether the buyer lives in the home or rents it out. I used the same maintenance expense for each case because I wanted to focus on how the home dividend is affected by the different tax rules for owner-occupied homes and rental properties.

In practice, the maintenance costs are probably going to be higher if the home is rented. Table 16-4 shows that if the maintenance expenses are doubled, from $1,350 to $2,700, the home dividend falls from $1,952 to $602. The home dividend is almost gone!

Rental income |

$15,000 |

Mortgage payment |

–$7,522 |

Property tax |

–$3,564 |

Taxes |

0 |

Insurance |

–$612 |

Utilities |

0 |

Maintenance |

–$2,700 |

Home dividend |

$602 |

If we allow for slightly higher maintenance expenses and/or months when the home is vacant, the home dividend can turn negative. This home might still be attractive as a rental property because we are only looking at the first-year home dividend, and the home dividend is likely to improve over time as rents increase and mortgage payments do not. The point is simply that the home dividend can be a lot lower for a rental property than for an owner-occupied home.

There are two lessons. First, just like the home you live in, the investment value of a rental property depends on the home dividend. Second, a home can look a lot more financially attractive if you are buying a home to live in than if you are buying the home so that you can rent it to someone else.