CHAPTER 4

Down Payments and How They Impact Your Mortgage

Down payments are in essence your very own “earnest money” in the deal. Your down payment tells a lender that you are serious about buying a home and that you’re willing to pony up some cash at the beginning to prove it.

4.1 WHAT EXACTLY IS A DOWN PAYMENT?

A down payment is your initial money into your purchase. A down payment is one of the risk elements lenders evaluate when making a mortgage loan, and it goes a long way in helping a lender make a loan. The more down payment from the borrower, the more risk a lender might take. The less down payment from the borrower, the less risk a lender might take.

TELL ME MORE

A down payment is calculated as a percentage of the sales price. If your sales price is $100,000 and you put 10 percent down, your down payment would be $10,000. Actually, lenders use the lesser of the sales price or appraised value. If your sales price is $100,000 but your appraisal comes in at $95,000, then your lender bases your application on the $95,000 value. Allowing for a 10 percent down payment of $9,500, your loan amount would then be $85,500. Now you’re in a pickle. Since you agreed to pay the seller $100,000, you now have to come up with the difference, or $14,500.

That’s why most sales contracts have something in them that says, “This deal is off if the appraisal doesn’t come in at or above the sales price.” It’s worded a little differently than that, I know, but usually if the appraisal doesn’t come in, the deal either falls through or the seller reduces the price.

Conversely, if your property appraises at higher than the sales price, lenders will still base your loan amount on the lower of the sales price or appraised value. If the property appraises at $110,000 rather than the sales price of $100,000, lenders won’t give you credit for the extra $10,000. After a year they will, when you’ve owned the home for 12 months or more, but not at the very beginning.

A down payment can come from a variety of sources, but primarily it must come from your very own funds; if given as a gift, it must come from a family member or qualified foundation. It is also your very first equity in your home and is basically whatever it takes to get an approved loan amount. As soon as you take ownership, you’ve already got some of your own money in the deal. And a down payment can sway an approval one way or the other.

Let’s say that you really, really want this house that just came up on the market, but it is just out of your reach from a debt ratio standpoint. If you put 5 percent down and your ratios are above 50, then a lender might not approve your loan. If you put 10 percent or even 20 percent down, a lender will allow other risk elements to relax.

4.2 WHAT ARE THE RISK ELEMENTS?

Risk elements are your gross monthly income compared to your monthly obligations. It’s a comparison of your debt ratios and your credit standing, plus the equity in the home. Capacity, credit, and collateral.

If your credit is less than stellar, or if you have some negative items on your credit report, such as late payments or collection accounts, you’ll have a harder time qualifying for a regular loan. To offset negative credit, try putting more money down or reducing your debt load. Or simply buy a smaller home. If your debt ratios are too high for a particular loan program, you may still get approved if you have excellent credit. If one of your risk elements needs work, try offsetting it with other risk elements.

4.3 HOW DO I KNOW HOW MUCH TO IMPROVE ANOTHER RISK ELEMENT?

There’s no formula. You can figure out what works with a little trial and error. If you apply for a mortgage and want to put 5 percent down and don’t get an approval, try the same application with 10 percent down. If that doesn’t work, then try 15 percent. While you may not immediately have those funds available, at least you will know how much you’re going to need in the future.

If you’ve saved up 5 percent of your own money but your lender wants 10 percent, start saving for the other 5 percent, get a gift from a relative, or find other funds to make up the difference.

Remember, the method for getting a mortgage is to get approved first, get the document later. There is no sense in getting every bit of your financial data together only to find out that you can’t qualify.

4.4 WHAT KINDS OF ACCOUNTS CAN I USE TO FUND THE DOWN PAYMENT?

A down payment must be your very own blood, sweat, and tears. Lenders want your down payment to come from your own savings or checking accounts. Other people can’t make it for you, though they can help by giving a gift. Otherwise, it has to come from you. There are programs that require no down payment whatsoever, and loan programs that let you borrow your down payment, but most every loan available will require a down payment of some type.

TELL ME MORE

First and foremost will be the money in your checking or savings accounts. Your lender will typically ask for account statements for the preceding three or more months to verify your funds to close the deal. Why three months? A lender wants to see a pattern or history of an account. If suddenly $20,000 pops into your bank account, the lender wants to know where it came from. Did you borrow it from someone else? Are you obligated to pay it back?

By providing three or more months of statements, you can make it clear to the lender that the funds you’ve saved came from you and you only. Some home buyers are in fact advised by some loan officers to simply “put some money in the bank and call me back in three months,” assuming that the lender won’t care where the funds came from, if in fact they’ve been in an account for that period. Quite true. It’s also quite true that lenders can ask for more than three months. They can mostly ask for whatever they want if they think they’re having the wool pulled over their eyes.

Your funds can come from your job, a bonus, your regular savings, selling something, or borrowing against an asset. Your paycheck can certify that you’re getting a certain amount each month, and you can verify that it’s going into a bank account. Same with any bonus or commissioned income. It’s documented as you make it.

Some people have assets they can sell for down payment money. Do you have a car you can sell? Artwork? Stocks? The key to selling an asset is that, first, you need to document the transaction, and, second, the object sold must be an appraisable asset.

An appraisable asset is an item whose value can be determined by a third-party expert. That car you want to sell? It’s an appraisable asset. Its value is independently appraised by a variety of automobile pricing schedules or even classified advertising. Do you have an expensive watch or heirloom jewelry? If the item can be appraised—in this instance by a gemologist or jeweler—and sold, then you can use those funds to buy the house.

Another form of down payment can come from a pledged asset, which is typically a stock or investment account that you can borrow against for a down payment. The stocks aren’t cashed in; you simply pledge the asset as collateral for down payment funds. If it can’t be appraised, the lender may not be able to use those funds for a down payment.

If you can’t document where your down payment is coming from, many loans won’t allow for that. Lenders want to be absolutely certain that the money you used to buy the house is not borrowed from another source. Borrowing from another source will affect your debt ratios and your collateral. It also affects your equity in the property and increases the risk in the loan. That’s why people can’t take out cash from their credit cards for down payments. The money’s borrowed. Lenders want to see you save your down payment.

4.5 CAN I BORROW AGAINST MY RETIREMENT ACCOUNT?

Sure you can, if your plan allows you to do so. Lenders have allowances to borrow all or part of a down payment from a retirement account, like a 401(k) plan, as long as they get to see the terms of your repayment and they are acceptable to them. Most plans are acceptable to lenders, but typically a lender wants to verify that the loan repayment won’t affect your ability to repay other debts, including your new mortgage.

I’ve personally closed millions in deals where people used their retirement funds to help them buy the home. Another bonus is that even though you now have a 401(k) loan with a new monthly payment, your lender won’t count that new payment in with your debt ratios.

Contact your employer or plan administrator and tell them you’re getting ready to buy a home and would like to explore borrowing against your 401(k). There is typically a time lag of, say, two to four weeks, or even longer. So if you plan to borrow against your 401(k), start this process early. It’s not something that happens overnight.

After you apply for the loan, document that you received the funds and show your lender where those funds are.

There are retirement plans that don’t allow for any loan whatsoever, although those are few. Nevertheless, don’t assume that it’s okay to borrow against your retirement plan. Check into it before you get started.

4.6 CAN MY FAMILY HELP ME OUT WITH A DOWN PAYMENT?

Of course any family member can help you out. If you are one of the chosen few fortunate enough to have relatives who can provide you with money for down payment funds, they are certainly a great source. What a deal, right? No saving, no borrowing, just show up. These are called, oddly enough, gift funds. Recent changes to “gift” requirements allow only immediate family members, churches, government agencies, and labor unions to make gifts to help with down payments and closing costs. Gift funds carry their own rules as well (go figure), but knowing in advance what a lender requires for gifts will help make your closing go a lot smoother.

TELL ME MORE

Most lenders also ask for a gift affidavit, a form signed by the givers swearing that the money they’re giving you is indeed a gift, not a loan, and is to be used for the purchase of a home. Lenders would like to see that form as well as a paper trail of the gift funds. If Mom and Dad are giving you $10,000, lenders want to see the gift affidavit, sometimes a copy of the check or wire transfer, and a copy of the deposit showing the gift funds being added to your own funds.

Even though you’re getting a gift, most loans require that you have additional funds lying around somewhere after the deal is closed. These funds, called cash reserves, typically require you to have up to 5 percent of the sales price of the home of your own money in addition to the gift, regardless of whether you use any of your money. If you buy a $75,000 home and get $7,500 as a present from your folks, the lender will want to verify another $3,750 of your funds in an account somewhere.

This requirement for 5 percent of your own funds is waived, however, if your gift represents 20 percent or more of the price of the home. Now that’s a deal: getting your down payment in the form of a gift, without mortgage insurance or piggyback financing, and no verification of 5 percent of your own money.

4.7 WHAT DO I DO IF I DON’T HAVE A DOWN PAYMENT SAVED?

There are organizations whose job it is to assist people with their down payments. Many times these are nonprofits dedicated to getting people into their first home. Being a first-time home buyer is usually a requirement, but not always. Down payment assistance programs (DPAPs) will either loan you the money for a down payment and/or closing costs or flat out give it to you. The first place to begin looking for a DPAP is to ask your lender about sources of DPAPs in your area. They can be sponsored by a local city, county, or state organization whose sole job is to help people buy their own home.

4.8 WHAT IS A “SELLER-ASSISTED” DPAP?

Organizations that are not government agencies with their very own nonprofit status also have DPAPs. Recent IRS rulings, however, have made such entities rare, putting most out of business. Be aware of the fact that if the DPAP agency is not a government entity, it may be illegal in the IRS’s mind.

TELL ME MORE

When any lender makes a loan that has a DPAP involved, the lender will review the current 501(c)(3) status of the organization to see whether its nonprofit status has been revoked. Organizations ran afoul of IRS rulings, and certain nonprofit agencies were determined to be, in fact, “for profit” enterprises when they would charge a fee to process the transaction.

Sometimes called a “seller-assisted” DPAP, the process worked like this: The sales price of a home would be, say, $200,000, but the buyer wouldn’t have any money for a down payment. If the buyer needed 5 percent of the sales price, or $10,000, the seller would raise the price of the home to $210,000, pay the “nonprofit” a small fee of perhaps $500, and send the $10,000 to the nonprofit, which would forward the $10,000 to closing and keep the $500. In this fashion, the seller wasn’t technically giving the down payment money directly to the buyer—which mortgage loans prohibit. But, in effect, the seller was doing just that, and the nonprofit kept the $500.

Money for these programs can vary from government bond issues that are established for first-time home buyers to participation fees paid to the DPAP by lenders, builders, or borrowers. Although the guidelines can vary from county to county, they are similar in that you either get the money in the form of a gift with no expectation of payback, a second mortgage placed on your new house with deferred payments, or a second mortgage placed on your home that you pay back only when you sell the home.

Most of the bond programs are offered in city or metropolitan areas, so your mileage may vary. That is to say, loans or gifts will usually be limited to 5 percent of the sales price of the home, but since the programs are locally run, their requirements may differ. They may also require that the borrower have a minimum investment in the property of $1,000 or perhaps 1 percent of the sales price. Many of these programs require that the borrowers enroll in and successfully complete a home-buying and home ownership course, and that they must also be approved for their main mortgage.

But in practice, here’s how these programs work: Say you want to buy a $100,000 home and need money for 5 percent down, or $5,000. You make a DPAP application, and the organization will supply you with a gift or a loan that will be used for the down payment. If it’s a loan, it will be in the form of a second mortgage and will remain there until you sell the home, refinance, or otherwise retire the loan. The terms for the second mortgage may differ from plan to plan, but the rates are competitive with most other second mortgages. Some require a minimum monthly payment, some defer the payment, and some have no repayment required at all. At the same time, you apply for a standard mortgage with your mortgage lender. Your lender will approve you based on the new mortgage and the DPAP.

4.9 HOW DO I KNOW IF I QUALIFY FOR A DOWN PAYMENT ASSISTANCE PROGRAM?

You have to contact one of these programs and ask. There are no universal guidelines, but most programs expect you to be a first-time home buyer and to take an educational course (some require it, some suggest it). Many ask that you fall into certain income limitations or live in a certain area, while others have no restrictions at all. Certain communities may in fact have more than one DPAP available, run by different organizations. A municipality may have one program while at the same time the county and state can have their own programs. If you don’t qualify for one DPAP, find another.

4.10 IS THERE AN IDEAL AMOUNT I SHOULD PUT DOWN ON A HOME?

That depends largely on how much you have, or will have, available. The main issue concerning down payments is the amount you actually put down. Historically, mortgages required that the borrower put down a minimum of 20 percent in order to get a mortgage loan. No 20 percent down? No home. You had to wait.

As you can imagine, this requirement locked many people out of the home ownership loop. Then, in 1934, the federal government, through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, established the Federal Housing Administration, or FHA. Guaranteed by the U.S. government, FHA loans asked for only 3 percent to 5 percent down. These loans became a welcome alternative for the home-buying public. But the private sector still asked for 20 percent down. Or more.

In 1957, a private company called Mortgage Guaranty Insurance Corporation (MGIC) stepped into the fray. If a lender required 20 percent down and the borrowers had only, say, 10 percent down, MGIC would issue an insurance policy, payable to the lender, for the remaining 10 percent should the borrower default on the original loan. If the borrower only had 5 percent down, MGIC would issue a policy for the remaining 15 percent, and so on. This is an insurance policy, paid by the borrowers, to guarantee that, should they default, the lender would get the remaining difference. It only covers the difference between what you put down as your down payment and the required 20 percent down.

Mortgage insurance was a big hit, so naturally other companies joined the party. That’s the way it is now. If you put down less than 20 percent, you can expect to pay mortgage insurance. That, more than anything else, can help you decide how much to pay.

4.11 HOW MUCH IS A MORTGAGE INSURANCE POLICY?

Mortgage insurance (MI), also known as private mortgage insurance (PMI), is simply another form of insurance. The cost is based on the type of loan program—fixed or adjustable—and the amount of the down payment. It is not insurance to pay off the mortgage in case you die or become disabled. Like any other policy, it can vary based upon a variety of other risk factors. For example, if you were looking for home insurance, your agent might ask you if your house was made of brick or made of straw. Brick houses don’t burn like straw ones do and they can’t be huffed and puffed and blown down by a storybook character. That’s an exaggeration, I know, but the principle is the same. The more risk, the higher the policy. Rates can also be marginally different based upon geography as well.

TELL ME MORE

If you put 5 percent down, there is a greater risk to the mortgage insurance company because they’re covering more in case you default. Conversely, if you put 15 percent down, the risk decreases, so the premiums are lower. There are even loan programs with nothing down, but again the insurance premium is higher.

Another risk factor is the type of mortgage loan you select. Insurers are more able to project risk if your mortgage loan payments are fixed throughout the life of the loan. If you have a mortgage where the payments can vary throughout the term, then the insurer may charge more due to that added layer of uncertainty. There are also levels of coverage to the lender that can affect price, as well as whether you pay for your insurance premiums up front or monthly.

To get an idea of how much your mortgage insurance premium would be, an average multiplier for fixed rates can help. For most 30-year fixed-rate loans with 5 percent down, the multiplier is 0.75 percent. For 10 percent down it is 0.49 percent, and with 15 percent down it is 0.29 percent. And for loans with zero down the multiplier can be 1 percent or more.

Simply take the multiplier times your total loan amount and divide by 12 to get a monthly payment amount. If your loan is $100,000, a 0.75 percent multiplier is $100,000 × .0075 = $750. Divide that by 12 and your monthly premium is $62.50. With 10 percent down on the same loan, it’s $100,000 × .0049 = $490. Then $490 ÷ 12 = $40.83, which is your monthly payment.

4.12 CAN I DEDUCT MORTGAGE INSURANCE FROM MY INCOME TAXES?

Historically, no. As an insurance policy, mortgage insurance has never been tax deductible as a separate payment—until a recent law was passed making it tax deductible. There are alternatives to mortgage insurance if you have less than 20 percent down, and one of the more common choices is a “piggyback” loan or second mortgage.

A second mortgage is just that, a mortgage behind your first mortgage. Remember that mortgage insurance is required if your loan is greater than 80 percent of the sales price. If you only have 10 percent down, you need to cover that other 10 percent. This can be done using mortgage insurance (as described previously), or you can use a second mortgage to cover the difference. This kind of loan structure is often called by its percentages, or an 80–10–10, with 80 percent being the first loan, 10 percent being the second loan, and the last 10 percent being your down payment.

TELL ME MORE

For a $150,000 home using an 80–10–10, your first mortgage will be for 80 percent of the sales price or $120,000, the second mortgage at 10 percent will be $15,000, and then finally there’s your very own 10 percent down payment of $15,000.

Rates and terms can vary, but a common comparison looks like this for a $100,000 home: For an 80–10–10, the first mortgage is at $80,000 and the second mortgage is for $10,000. Using a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage at 7 percent for the first mortgage, the payment is $532. Using a 15-year fixed-rate second mortgage at 9 percent on $10,000, the payment is $101, with a total monthly payment of $633.

Still using 10 percent down but with mortgage insurance, your first mortgage is at 90 percent of the sales price, or $90,000. A 30-year fixed-rate mortgage of 7 percent yields a $598 payment. Wow, a lot lower than $633, right? But don’t forget your mortgage insurance premium. Using a .0049 multiplier on $90,000 gives you a $36 monthly payment. Now add $36 to $598 and you can compare the two programs. An 80–10–10 loan adds up to $633, while the 10 percent down loan with mortgage insurance yields $634. Hardly a difference, right?

Potential tax deductions are moot for those who do not itemize each year on their income taxes. If you don’t itemize, then mortgage insurance deductions won’t apply to you. If you do itemize, this example gives you an income tax deduction of $432 at the end of the year. Note that this $432 doesn’t come straight off your tax bill; it’s deducted from your income before taxes are calculated. It’s a deduction from income, not a credit to the IRS. This example is a common one.

The 80–10–10 is the most common piggyback scenario, but another common arrangement requires a little more scrutiny. That’s the 80–15–5. It’s a similar transaction but with just 5 percent down from you and a 15 percent second mortgage. There are two increases in cost to the consumer for an 80–15–5 not found in the 80–10–10. The first is the mortgage insurance premium itself. With a 30-year fixed at 5 percent down, the mortgage insurance multiplier jumps from 0.49 percent to 0.75 percent on most policies. In addition, some loans increase the interest rate on the first by as much as 14 percent, so your new first payment goes to $538. Your second mortgage payment, again at 9 percent, will be $152, making your total mortgage payments $690.

Using a straight 95 percent mortgage, with 5 percent down and a mortgage insurance multiplier of .0075, your mortgage insurance payment goes to $50. Without the 80–15–5 scenario there is no add-on for the first mortgage rate, so it would stay at 7 percent but based upon a $95,000 loan amount, or $632. Your total payment with one mortgage and with mortgage insurance would then be $682, or $8 less than the 80–15–5 calculation.

It has to be noted that some lenders do not charge a premium on their rate for an 80–15–5 and instead may charge a fee, say 1 percent to 2 percent of the loan amount. It’s highly important not just to compare the advantages of mortgage insurance to a piggyback, but to compare the various offerings by different lenders on those programs. The trick with mortgage insurance is that the permanent deductibility is an annual event, meaning it has to get authorized by Congress every year. There is no guarantee the deductibility will continue, but when it does there are two qualifications:

1. Your adjusted gross income can be no greater than $100,000 for full deductibility and up to $109,000 for partial deductibility.

2. The loan must be either on your primary residence or second home and not for investment properties.

One consideration when comparing piggyback mortgages and mortgage insurance is that, as mortgage rates in general rise, the attractiveness of mortgage insurance rises. Mortgage insurance rates are set by a multiplier that never changes. A 0.49 percent multiplier on a conventional loan will always be 0.49, regardless of what rates do. When mortgage rates reach 8 percent or more, it will likely be your best choice to choose a loan with mortgage insurance.

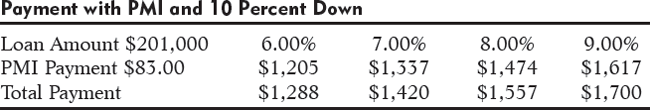

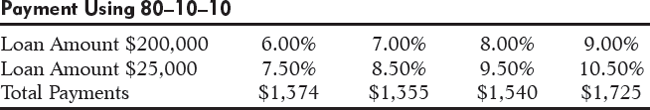

Let’s look at an example using a 30-year fixed rate on a $250,000 mortgage and compare various total payments with 10 percent down.

It used to be that, given a choice, a piggyback loan was hands down the better alternative due to the nondeductibility of mortgage insurance, but no longer.

4.13 CAN I “BORROW” MY MORTGAGE INSURANCE?

Yes, you can, on some policies. You do so by rolling your PMI into your loan. It’s another alternative to piggyback mortgages and mortgage insurance, called a financed premium, which you should review and compare. This program allows for the borrower to buy a mortgage insurance premium and roll the cost of the premium into the loan amount in lieu of paying a mortgage insurance payment every month. The program came about just a few years ago, but for some reason it’s never really gotten off the ground. However, when compared to an 80–10–10 program, it’s worth examining further.

TELL ME MORE

Let’s look at a typical transaction on a $200,000 home with 10 percent down. With an 80–10–10 program, the first mortgage amount would be for 80 percent of $200,000, or $160,000, with the second mortgage at 10 percent of the sales price, or $20,000.

Using a 30-year fixed rate of 7 percent on the first, and a 15-year rate of 8 percent on the second mortgage, the payments work out to be $1,058 and $189, respectively, for a total payment of $1,247. With 10 percent down and a monthly PMI premium, the mortgage payment at 7 percent on $180,000 would be $1,190, with a mortgage insurance premium of $36, for a total of $1,226.

Now look at paying for mortgage insurance with one premium and rolling that premium into your loan. With 10 percent down, the financed premium cost is around $3,780. Add this number into your principal balance of $180,000 and again use the 7 percent 30-year rate. The new loan amount will be higher, and yes, you’re adding to your principal, but now you have one loan at $183,780 and a payment of $1,215 using the same 30-year rate of 7 percent. Two things are happening here. First, the payment is lower than the other two options of 10 percent down with monthly mortgage insurance, and second, the interest on the full $1,215 payment is also tax deductible.

There are some detractors of the program, but really the only drawback is that it adds to your principal balance, and the cost of that $3,780 spread over 30 years gets expensive, adding over $5,000 in additional interest. True, but there are also financed mortgage insurance programs that are refundable when the loan is refinanced. This is such a solid program I’m not certain why it’s not more popular. As a matter of fact, I used this very same program to buy my first home in Austin.

4.14 WILL PMI COME OFF MY MORTGAGE AUTOMATICALLY?

If you had to put less than 20 percent down or otherwise had to come up with a PMI payment each month, it’s not likely that PMI will be on your conventional loan forever. In fact, federal law requires that PMI be dropped from your loan when your loan automatically goes below 80 percent of the original value of your home. That’s a gradual reduction in loan balance made simply by paying the mortgage down. It can take several years for that to happen. But there are other ways you can reach that magical “20 percent” equity position other than with a simple paydown.

As a rule of thumb, most PMI policies will stay on your loan for a minimum of two years before you can do anything; that said, here are some ways to accelerate your equity so you can get PMI off your loan.

TELL ME MORE

The first way is to increase the value of your home by remodeling or making improvements or additions. If you bought a three-bedroom home for $100,000 and a year later added another bath and bedroom, you might very well have increased the value of your home by $15,000 or more—especially if all the other houses in your area are also four-bedroom homes.

Another way to increase your equity position is by appreciation. Have home values increased since you first bought? If you could sell your home for more than what you paid for it, then that increase in appreciation can be used to help remove PMI. Still another way is to simply pay down the mortgage balance by writing a check.

Any combination of any of these methods will also work. Note that, due to seasoning requirements, you won’t be able to affect the equity in any manner if it’s been less than 12 months since you first bought the house. But if you’ve had your loan for more than a year, then the next step is up to you. You have to call your lender and ask them to begin the process to drop PMI coverage. You’ll have to shell out $300 or so for a brand-new appraisal, but it’s worth it if you think you can drop your coverage. If your appraisal comes back and indeed shows that your loan-to-value ratio is less than 80 percent, then your lender will begin the process to drop PMI.

There are various companies that advertise how to get PMI dropped from your loan, and they charge you a fee to disclose all their “secret” ways to drop PMI. Save your money; those secrets were just revealed here.

4.15 WHAT ABOUT “ZERO-MONEY-DOWN” LOANS?

There are two primary zero-money-down loans in today’s marketplace and they’re both government-backed. These two mortgage programs are the VA and USDA options. Both mortgage loan programs do not require a down payment but there are specific qualification guidelines for each loan.

TELL ME MORE

We’ll talk more in depth about these two zero-down loan programs in Chapter 7, but for those who qualify for the VA home loan and want to come to the closing with as little cash as possible, the VA loan is the ideal choice. No down payment, low closing costs, and extremely competitive interest rates.

The USDA loan also asks for nothing down but is restricted by zip code and also has income limitations for those who will be living in the property. Both VA and USDA mortgages are government-backed and the lender is compensated for some or all of the loss should a home go into foreclosure.

4.16 WHAT IS THE CONVENTIONAL 97 OR HOMEREADY PROGRAM?

The Conventional 97 is the conventional loan with the closest resemblance to loans underwritten to Fannie Mae guidelines; it is a mortgage program introduced by Fannie Mae that requires only a 3 percent down payment, even lower than the 3.5 percent down payment requirement for the FHA loan. This program is now referred to as the HomeReady program. It is still relatively little used but is an excellent option for those seeking to buy and finance a home with as little cash as possible but are not eligible for a VA or USDA loan.

TELL ME MORE

With just 3 percent down, the HomeReady program is very competitive and should be looked at as an option when an FHA loan is a consideration. There is no requirement that the borrowers need to be first-time buyers and the entire amount of the down payment and closing costs can come from a gift, a grant, or cash on hand. Most lenders require the credit score to be no lower than 620 for this program.

The loan program also allows for slightly higher debt-to-income ratios as well, even as high as 50. Mortgage insurance is required but the monthly premium is reduced and lower compared to government-backed programs. There are no income limitations for the borrowers as long as the property is located within an area considered to be in or formerly in a disaster area. In an area where minorities make up 30 percent or more of the population, borrower income is limited to 100 percent of the median income for the area.

4.17 HOW DO I BUY A HOUSE IF I NEED TO SELL MY HOUSE FOR MY DOWN PAYMENT?

Get a temporary loan on your current house, called a bridge loan, to cover down payment and closing costs for the new home. More on that below.

It’s also common to buy a new house on a “contingency” basis, meaning “I’ll buy your house if I’m able to sell the house I’m in now.” If the sellers of the property you want to buy have someone who is going to give them cash right now or who doesn’t have a contingency clause, then you may lose out. Much depends upon the condition of the local real estate market; in a slow market, the seller may be willing to accept such conditions. In a brisk market, maybe not, unless you ante up the price a bit.

You need to speak with a real estate agent about local market conditions and whether the market is currently accepting contingency offers. But there are ways to buy the new home without having to sell your current one simultaneously.

TELL ME MORE

For example, say you found a house you want to buy that costs $150,000. The house you’re in would sell for $130,000 and you have about $30,000 in equity. If you sold your house today, you would pay off your mortgage and walk away with $30,000, less associated selling charges. But you can’t sell your home right away. It might take a month or two, or even more. And the house you really, really want has just now come on the market and you don’t want to lose it.

First, use your current equity. You can get what is called a bridge loan, which allows you to borrow, temporarily, on your current house in order to buy the new home. These loans “bridge” the gap between the purchase of your new home and the sale of your present one. Your bridge lender, typically your banking institution or credit union, will loan you the money to buy the new house, place a lien on your current one, and expect to be paid off when your home sells.

Next, how much should you borrow using a bridge loan? Since bridge loans are short term and carry a higher rate, borrow as little as possible, usually just enough for down payment and perhaps for closing or moving costs. If your bridge loan was for $10,000, that would be enough for your 5 percent down payment of $7,500 and leave an extra $2,500 for other expenses.

A common strategy is to use a piggyback loan. An 80–15–5 is a good strategy for the $150,000 purchase price in this example, with a first loan of 80 percent ($120,000), a second loan of 15 percent ($22,500), and the 5 percent down payment ($7,500) coming from your bridge loan. This strategy gets you into the home with minimal investment while also avoiding mortgage insurance. When your old home sells, you pay off the old mortgage, the bridge loan, and the new second mortgage you placed on your new home, leaving just the $120,000 first mortgage.

4.18 WILL I HAVE TO QUALIFY WITH TWO MORTGAGES?

You’ll have to be able to afford both payments. There’s no sense in using this strategy if it’s nearly impossible to pay all the mortgages on time. But yes, both mortgages will be counted against you, and a lender won’t let you use a bridge if your ratios zoom into the stratosphere.

An alternative would be to rent your current property to either offset or entirely pay for your old mortgage. You’ll need to have a 12-month lease agreement signed by your new tenants. But without a renter, if your debt ratios jump from 28 temporarily to 55 or 60, you should still be okay as long as you have good credit. If you’re concerned, the first thing you should do is ask your loan officer to send your application through an AUS using both mortgages to qualify you.

Some loan programs make individual allowances for high debt ratios and don’t use an AUS. Instead, they look to see if the transaction makes sense. If you’re selling your current property, the lender might want to see a copy of the listing agreement showing that your home is in fact on the market and you intend to sell soon.

Do you have solid cash reserves? Are you able to show that you can make these new payments from liquid accounts? Better still, if you can provide a sales contract on the house you’re selling, the lender might not count the new mortgage at all. If this is your situation and you need to leverage your current property to buy a new one, then a bridge loan is a good alternative.