2 Reporting frameworks

The global financial community consists of a number of public and private actors. To begin with, there is the Financial Stability Board that includes the G20 major economies and ultimately endorsed the development of the TCFD. There are also more specialized international banking, insurance, and investor international government collaborations. Within countries, there are financial supervisors and regulators either at the national or subnational level. Among private actors, there are banks that lend capital to consumers for activities such as purchasing private property. There are insurers that issue policies to consumers and reinsurers that hold portions of insurers’ risks for paying out on those policies. There are rating agencies that evaluate these companies to assess their creditworthiness. There are also modelers and third-party data providers that develop and sell analytical tools to these companies.

When the global financial community turned its attention to evaluating carbon risks, analytical tools were already being used. However, those tools were generally not tailored for financial institutions. While informative, the tools allowed for significant variation and predominantly qualitative assessments. This was dissimilar from more precise and quantitative tools typically relied on within the financial community. More recently, though, analytical tools, such as reporting frameworks, have become increasingly sophisticated, with comparable metrics across users.

Reporting frameworks have always had value because, at a minimum, they encouraged companies to internally convene, collect information, set targets, and track progress. However, with more comparable metrics, reporting frameworks are allowing companies to see how they are performing with respect to their peers and garner information on best practices with a range of analytical tools. Reporting frameworks now ask for advanced carbon footprint metrics, allow for discussion on divestment and engagement using brown taxonomies and investment using green taxonomies, and seek information on scenario analysis for assets and stress testing for liabilities.

2.1 Development

With companies starting to track their carbon footprints, a nonprofit organization, CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project), realized that there was value in assembling this information in a central location. It started collecting carbon footprints from companies, building the world’s largest database of carbon footprints. Over time, realizing that other climate-related information was being assembled and had practical value, CDP increasingly sought additional climate-related information from companies. In the process, CDP developed a voluntary reporting framework for companies wishing to report on risks and opportunities presented by climate change.

While the CDP methodology has become somewhat of an industry standard, with other reporting frameworks even emulating it, today there are a number of reporting frameworks covering various sectors and having different focuses. There are a number of established voluntary frameworks managed by nonprofit organizations, such as CDP, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB) with the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB). There are also mandatory frameworks that government financial regulators have been developing, in particular a framework developed for large companies operating in France and insurance companies operating in certain jurisdictions within the United States.

2.2 Harmonization with Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures recommendations

Major reporting frameworks are now embracing the TCFD recommendations. Although reporting frameworks began with a focus on collecting carbon footprints, and the collection of this data remains important, reporting frameworks now seek various metrics on how companies are responding to climate change. The questions are being mapped to the TCFD recommendations. In fact, several of the leading reporting framework developers, including CDP, GRI, and CDSB with SASB, are even collaborating to further map their reporting frameworks to the TCFD recommendations, which cover governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets, as detailed in Table 2.1.

2.2.1 CDP climate change questionnaire

When CDP started collecting climate information in 2002, there were a couple hundred companies providing information. However, now, thousands of companies are reporting through CDP (CDP n.d.a). This accounts for nearly sixty percent of global market capitalization and a significant portion of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions (GRI and CDP 2017).

| Governance | Strategy | Risk Management | Metrics and Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disclose the company’s governance around climate-related risks and opportunities. a) Describe the board’s oversight and b) Describe management’s role. |

Disclose the actual and potential impacts of climate-related risks and opportunities on the company’s business, strategy, and financial planning where such information is material. a) Describe risks and opportunities that have been identified over the short, medium, and long term and b) Describe the company’s strategy when considering climate scenarios such as 2 degrees or below 2 degrees Celsius scenarios. |

Disclose how the company identifies, assesses, and manages climate-related risks. a) Describe the company’s processes for identifying, assessing, and managing risks and b) Describe how these processes are integrated into the company’s overall risk management. |

Disclose the metrics and targets used to assess and manage relevant climate-related risks and opportunities where such information is material. a) Disclose metrics used by the company and b) Describe the targets used by the company (TCFD 2017, 14). |

Following a redesign in 2018, the online CDP climate change questionnaire provides a good example of what kind of information is sought by reporting frameworks and how a reporting framework can map to the TCFD recommendations (CDP n.d.b). First, the questionnaire itself both begins and ends with corporate governance questions. Questions get at who exactly within a company is making decisions on climate-related issues and what their authority is within the company, and whether there are rewards and targets related to any climate-related issues. The questionnaire also asks for details on the person who has approved responses, specifically asking for a job title and the selection of a job category that ranges in status. For some of these questions, a link is specifically drawn to the TCFD recommendations by identifying relevant TCFD recommendations on corporate governance, such as recommended disclosures on the board’s oversight of climate-related risks and opportunities and management’s role in assessing and managing climate-related risks and opportunities (CDP n.d.b).

Second, a focus of the questionnaire is how companies are identifying risks and opportunities, specifically with respect to a 2 degrees Celsius scenario. Questions in this area allow a company to describe how it identifies short-, medium-, and long-term climate-related issues. A company is asked to discuss how climate-related issues are integrated into its business strategy, specifically asking about the use of scenario analysis and what scenarios and other inputs are being used for this analysis. For some of these questions, a link is specifically drawn to the TCFD recommendations by identifying relevant TCFD recommendations on strategy, including describing the climate-related risks and opportunities that a company has identified over the short, medium, and long term; describing the impact of climate-related risks and opportunities on the company’s business, strategy, and financial planning; and describing the resilience of the company’s strategy, taking into consideration different climate scenarios, including a 2 degrees Celsius or lower scenario (CDP n.d.b).

Third, there are questions on how a company is responding to specific risks (e.g., current and emerging regulation, technological advancements, legal concerns, market shifts, reputational considerations, acute and chronic physical stress, and upstream and downstream challenges) and specific opportunities (e.g., increasing resource efficiency, identifying new energy sources, creating additional products and services, market shifts, and improving resilience). The questionnaire further probes whether a company has been employing specific desirable risk management strategies. For example, the questionnaire seeks information on energy consumption practices, value chain assessments, and publication of climate change information in places other than its CDP response. The questionnaire also has optional questions on supply chain assessments for products and services (CDP n.d.b).

Fourth, the questionnaire asks how a company is using metrics and targets, with an emphasis on carbon footprints. CDP maintains the largest collection of companies’ carbon footprints. Therefore, it is not surprising that large portions of its questionnaire are dedicated to collecting and evaluating how a company tracks greenhouse gas emissions. These areas of the questionnaire allow a company to provide Scope 1 emissions, which are direct emissions from owned or controlled sources; Scope 2 emissions, which are indirect emissions from the purchase of electricity; and, where available, Scope 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions that occur in the value chain. The questionnaire asks for a breakdown of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by greenhouse gas type for the six greenhouse gases that are restricted by the international Kyoto Protocol treaty: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, and sulfur hexafluoride. The questionnaire asks for a breakdown of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions by country/region, business division, facility, and activity. Moreover, the questionnaire asks for carbon intensity metrics, which are advanced carbon footprint metrics that quantify emissions in relation to business and investment operations. The questionnaire also asks a company to identify standards, protocols, and methodologies used to calculate emissions, such as the Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (CDP n.d.b). The questionnaire asks about year over year comparisons of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions and reasons for any changes. The questionnaire further asks for verification for emissions data and to discuss any emissions targets and progress against those targets (CDP n.d.b). For some carbon footprint questions, a link is specifically drawn to the TCFD recommendations by identifying relevant TCFD recommendations on metrics and targets, including disclosing the metrics used by the company to assess climate-related risks and opportunities in line with its strategy and risks management process, disclosing Scope 1, Scope 2, and, if appropriate, Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions and related risks and describing the targets used by the company to manage climate-related risks and opportunities and performance against targets (CDP n.d.b). More than ninety percent of the Fortune 500 companies reporting to CDP used the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard or a methodology based on the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard to report their emissions (GHG Protocol 2020).

As far as structure, the CDP climate change questionnaire allows for a broad range of companies to provide responses. However, it can also be tailored to specific types of companies, taking into account any sectors that the company operates in and their ability to provide comprehensive responses. When first entering information for a company, the CDP website prompts whoever is entering data to identify whether the company operates in one or more of a dozen high-impact sectors, which will prompt the user to answer additional questions for those sectors. The CDP website then allows the company to select a minimum or full version. The minimum version contains identical but fewer questions and no sector-specific questions. CDP states that the minimum version can be used by smaller companies or by companies responding to the questionnaire for the first time. A company can also decide to respond to additional supply chain questions. The survey has yes/no, multiple-choice, and open-text questions, allowing for comprehensive, comparable data (CDP n.d.b).

After completing the CDP climate change questionnaire, the person who has entered information for a company will receive an email with scored results for the company. Not all information is made publicly available, but public responses for thousands of companies can still be viewed on the CDP website. CDP also lists over one hundred companies identified as “climate change A list,” an identification which is good for a company’s reputation (CDP n.d.b).

2.2.2 Global Reporting Initiative Sustainability Reporting Standards

Prior to the rollout of the CDP questionnaire, nonprofit organizations, including the Ceres and the United Nations, formed GRI. The GRI has developed Sustainability Reporting Standards (formerly referred to as “Guidelines”). These were first published in 2000 and now have thousands of users that rely on them to publish sustainability reports (GRI 2020).

In 2016, the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards were redone. This redrafting more closely aligns them with the TCFD recommendations that were being developed at the time. Major changes have had to do with an increased emphasis on management’s approach to material disclosures and consideration of supply chain impacts. More minor changes related to modifying terminology so that it more closely reflects usage in the international financial community, such as using the term “disclosure” rather than “indicator” (GRI 2020).

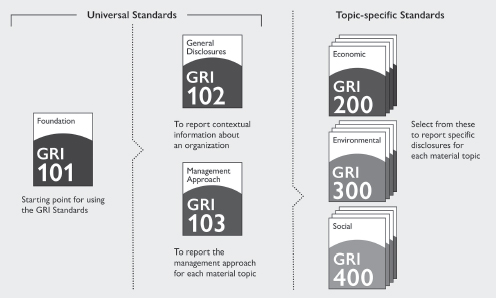

The redrafting of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards also made them easier to use. The GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards now have a modular structure (GRI 2020), making it easier for a company to update information, since attention may only be needed in certain areas, and allowing for reporting only on specific areas. Moreover, the modular structure also allows for reporting on specific areas rather than a single comprehensive report (GRI 2020). Figure 2.1 shows the current modular structure of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards.

As shown in the figure, the modular structure includes three universal standards and a number of topic-specific standards. A comprehensive report would include a report with information for the three universal standards and information on applicable areas of topic-specific standards. A report on a specific area would instead include a report on an applicable topic-specific standard with management approach information discussing material information related to that specific standard (GRI 2020).

Source: Global Reporting Initiative. This image was viewable on July 25, 2020 on the following GRI website: www.globalreporting.org/information/news-and-press-center/Pages/Ready-for-GRI-Standards-The-release-date-is-announced!-.aspx. Per GRI, GRI is the independent international organization – headquartered in Amsterdam with regional offices around the world – that helps businesses, governments, and other organizations understand and communicate their sustainability impacts.

The GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards have a topic-specific standard for greenhouse gas emissions. The standard requires separately reporting gross Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions. In doing so, the standard seeks information on the following greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons, sulfur hexafluoride, and nitrogen trifluoride (GRI and GSSB 2016e, 4). The standard also seeks carbon intensity information (GRI and GSSB 2016e, 13). Moreover, the standard seeks information on methodologies, assumptions, and calculation tools that were used in composing greenhouse information (GRI and GSSB 2016e, 7–8, 11–13). The standard further asks for information on how the company’s initiatives have reduced greenhouse gas emissions (GRI and GSSB 2016e, 14).

Greenhouse gas emissions reporting through the GRI is similar in practice to reporting through CDP. CDP and the GRI worked closely together to ensure harmonization of greenhouse gas emission reporting, with CDP being an active contributor to the revision of GRI’s greenhouse has gas emissions disclosures. Harmonization has been achieved because both reporting frameworks rely extensively on the GHG Protocol Corporate Standard and GHG Protocol Scope 3 Corporate Standard (GRI and CDP 2017, 5). There are some distinctions between the two reporting frameworks, though. In particular, the GRI requires reporting Scope 3 emissions and an additional greenhouse gas beyond those restricted in the international Kyoto Protocol treaty, where doing so is voluntary with the CDP climate change questionnaire, although doing so would presumably lead to more favorable assessments of the reporting practices of companies in the CDP climate change questionnaire.

Other topic-specific standards are relevant to reporting on carbon risks and green finance opportunities. An energy standard seeks information on total energy consumption (GRI and GSSB 2016d, 6–7). An economic performance standard specifically seeks information on the financial implications of corporate actions (GRI and GSSB 2016c, 9–10). A public policy standard asks for information on public policy outreach, covering areas such as the management of carbon risks and potentially green finance (GRI and GSSB 2016f, 5–6).

The management approach standard is extremely relevant to reporting on carbon risks and potentially green finance. This standard asks for information on material topics, which GRI defines as topics that reflect “significant economic, environmental and social impacts, or that substantively influences the assessments and decisions of stakeholders” (GRI and GSSB 2016b, 12). For each material topic, this standard seeks information on how a company manages the topic, including information on specific actions and goals and targets (GRI and GSSB 2016b, 6–11).

The general disclosures standards are also relevant to reporting on carbon risks and potentially green finance when preparing a comprehensive report. This standard seeks a statement from the company’s most senior decision maker, such as the company’s CEO, on the relevance of sustainability to the companies and the company’s sustainability strategy (GRI and GSSB 2016a, 14). This standard also seeks information on the process for delegating authority on sustainability issues (GRI and GSSB 2016a, 18). Further, this standard seeks information on the general composition of companies, including supply chain information (GRI and GSSB 2016a, 9–12).

The GRI allows companies to publish a sustainability reports that cover their entire Sustainability Reporting Standards or a limited scope of their Sustainability Reporting Standards. Companies that publish a sustainability report that covers a limited scope of the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards are asked to identify that they are doing such. All companies using the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards to publish sustainable reports are asked to report doing so to the GRI so that the GRI can track this, even though there are no costs associated with using the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards (GRI 2020).

2.2.3 Climate Disclosure Standards Board framework using Sustainability Accounting Standards Board standards

SASB is an organization that has developed investor-focused reporting standards for financially material environmental disclosures. In 2018, working with CDSB, SASB developed implementation guidance describing how SASB standards and the CDSB reporting framework can be used together to make TCFD disclosures. Doing so allows sections of the reporting framework, referred to as core elements, to specifically align with the TCFD recommendations. For instance, the reporting framework includes sections on governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets (CDSB and SASB 2019, 17–55). SASB states that a company using its standards with the CDSB reporting framework is well positioned to make TCFD disclosures. A SASB and CDSB implementation guide explains that the TCFD recommendations sought to establish common principles to help existing disclosure regimes more closely align over time. According to this guide,

The design of the CDSB reporting framework using SASB standards resembles that of other prominent climate change reporting frameworks. Similar to how the GRI and CDP reporting frameworks operate, a company has the ability to provide both qualitative and quantitative responses. However, this reporting framework is tailored to specific industries and focused on financial material disclosures (CDSB and SASB 2019, 17–55).

2.2.4 French Energy Transition Law

In addition to nonprofit climate change reporting frameworks, there are also government reporting frameworks that require mandatory disclosures. For example, in 2015, the French government adopted the world’s first national climate disclosure law, the French Energy Transition Law. The law went into effect the following year. The law requires companies to consider climate-related financial risks and report on how they are doing so (French Energy Transition Law 2015, Art. 173; 2DII 2015, 7; Mason et al. 2016).

The French Energy Transition Law does not currently map to the TCFD recommendations, but it covers some of the main recommendations. Therefore, a company can satisfy its requirements under the law through TCFD-aligned reporting. To begin with, with respect to strategy, the law asks a company for information on how climate change will present it with financial risks. Next, with respect to risk management, the law asks a company about any low-carbon strategies it is adopting to reduce these risks, in particular with the production of goods and provision of services. The law further requires investors to make certain financial information available to their beneficiaries. This includes information on how their investment decisions incorporate climate-related risks such as greenhouse gas emissions associated with their assets and information on actions taken to contribute to a transition to a low-carbon economy. Furthermore, with respect to metrics and targets, the law requires banks and credit institutions to disclose risks of excessive leverage that are shown through regularly implemented stress tests. If appropriate, institutional investors shall explain why contributions did not meet targets from a prior fiscal year. As far as structure, the French government has stated that listed companies shall disclose this qualitative information in an annual report (French Energy Transition Law 2015, Art. 173; 2DII 2015, 7; Mason et al. 2016). Collected information fits into the core elements of the TCFD-recommended climate-related financial disclosures as follows.

2.2.5 National Association of Insurance Commissioners Climate Risk Disclosure Survey

Some United States government agencies at the state level also have a sector-specific reporting framework, specifically those regulating the insurance sector. Several states in the United States have been requiring larger insurers operating in their jurisdiction to respond to a survey that has been organized in connection with the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), the NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey, modeled at least in part on an earlier version of the CDP climate change questionnaire (NAIC n.d.). The survey and supplemental guidance currently do not specifically map to the TCFD recommendations but cover many areas of the TCFD recommendations, and the most recent survey was sent to insurers with a cover letter explaining how the questions correspond to the TCFD recommendations (IAIS and SIF 2020, 37). To begin with, on governance, the survey is sent directly to the CEOs of insurers, and supplemental guidance asks about the role of the board of directors in managing carbon risk (CDI 2018, 2). Next, with respect to strategy, the survey seeks information on the current or anticipated risks that climate change presents to a company and the degree that climate change risks could impact a company’s business, including financial implications (CDI 2018, 3). Further, with respect to risk management, the survey asks about efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, investment strategies, preventing losses from climate change-influenced events, and public engagement (CDI 2018, 2–5). Finally, with respect to metrics and targets, the survey asks that a company describe actions being taken to manage the risks climate change poses to businesses, including, in general terms, the use of computer modeling (CDI 2018, 5). Supplemental guidance discusses measuring carbon footprints using the GHG Protocol (CDI 2018, 2). Collected information fits into the core elements of the TCFD recommended climate-related financial disclosures as follows.

As far as structure, the NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey allows a company to provide qualitative responses to eight questions covering areas such as efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions, investment strategies, preventing losses from climate change-influenced events, public engagement, and modeling (CDI n.d.). California, which is now taking the lead in implementing the survey, posts the survey results on a searchable database. A nonprofit investor organization, Ceres, has used the publicly available survey information to identify best actors (Messervy and McHale 2016). Results were also cited in California’s Trial by Fire report (Mills et al. 2018, 25–27, 32, 64–65, 67, 70, 73) and the joint TCFD paper of the Sustainable Insurance Forum and International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS and SIF 2018).

2.2.6 Comparing reporting frameworks

When comparing the more established climate change reporting frameworks, there are observable trends. To begin with, nearly all the reporting frameworks ask for information on board oversight. Next, all the reporting frameworks ask how carbon risks will impact a company, and almost all ask about opportunities, too. Nevertheless, not all reporting frameworks ask that the information be divided into disclosures on short-, medium-, and long-term impacts. Further, all the reporting frameworks seek information on how companies are managing carbon risks. Moreover, all the reporting frameworks also ask about metrics and targets, at least in certain instances. The metrics that are specifically identified include carbon footprints, scenario analysis, and stress tests. Table 2.2 compares the content of these different reporting frameworks.

However, while the reporting frameworks seek a lot of similar information, there are some important structural distinctions. First, some reporting frameworks require a submission to the entities overseeing the implementation of the framework. However, others encourage a company itself to publish a sustainability report or direct a company to provide disclosures in an annual report. Second, the reporting frameworks are for different types of companies. Most of the voluntary reporting frameworks are set up for all companies. The mandatory reporting frameworks, however, are for specific types of business. This is because the entity administering the framework has chosen a subset of businesses either to facilitate compliance or to ensure that the entity administering the framework has proper authority. Table 2.3 provides a comparison of the structure of some of the major climate change reporting frameworks.

Building on information sought by and provided through reporting frameworks, London School of Economics researchers have made a major breakthrough in tracking the efforts of companies to address carbon risks. These researchers developed a Transition Pathway Initiative tool that scores a company’s efforts to address carbon risks on a staircase using publicly available information gathered by a third-party data provider. The Transition Pathway Initiative tool assigns climate action ranks based on a company’s efforts, ranging from Levels 0 to 4. Various indicators are used to determine where a company fits within the ranges from Levels 0 to 4. As with the developers of reporting frameworks, developers of the Transition Pathway Initiative tool have mapped these indicators against the TCFD recommendations (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 4–13). This ensures that rankings appropriately consider governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets.

| Governance | Strategy | Risk Management | Metrics and Targets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDP Climate Change Questionnaire | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CDSB Framework Using SASB Standards | Yes | Yes, without timelines | Yes | Yes |

| French Energy Transition Law | No | Yes, without timelines | Yes | Yes, in certain instances |

| NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey | Yes | Yes, for risks without timelines | Yes | Yes |

| Information | Method | Applicability | Requirement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDP Climate Change Questionnaire | Qualitative and Quantitative | Submit to CDP | All Businesses | Must Submit to Receive a Rating |

| GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards | Qualitative and Quantitative | Publish a Sustainability Report | All Businesses | Voluntary |

| CDSB Framework Using SASB Standards | Qualitative and Quantitative | Provide in Annual Report | All Businesses | Voluntary |

| French Energy Transition Law | Qualitative | Provide in Annual Report | Listed Businesses in France | Mandatory |

| NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey | Qualitative | Submit to Regulator | Insurers with US$100 Million or More in Annual Premium Licensed in California, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Washington | Mandatory |

To begin with, a company is ranked at Level 0 when it is unaware of or not acknowledging climate change as a business issue. In particular, a company is ranked at Level 0 when it is not taking one of several actions that show that it is acknowledging climate change as a significant issue for business. This includes, for instance, adopting a climate change policy or making a statement committing it to take action on climate change (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 9).

Next, a company is ranked at Level 1 when it is acknowledging climate change as a business issue but is not necessarily taking tangible steps to address climate change. In particular, a company is ranked at Level 1 when it does both of the following. First, the company adopted a climate change policy or has made a statement committing it to take action on climate change. Second, the company incorporated at least two of several advanced management practices demonstrating that it is recognizing climate change as a relevant risk or opportunity to its business (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 10).

Further, a company is ranked at Level 2 when it develops basic capabilities for addressing climate change, including management strategies and reporting procedures. A company is ranked at Level 2 when it does everything required at Level 1 and does both of the following. First, the company has set greenhouse gas emission reduction targets. Second, the company has published information on its Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gas emissions (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 10–11).

Moreover, a company is ranked at Level 3 when it is integrating addressing climate change into operation decision making. A company is ranked at Level 3 when it does everything required at Levels 1 and 2 and takes several significant actions to address climate change. Among other significant actions, this includes assigning senior management or board responsibilities for climate change and providing comprehensive disclosures that include verified Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions and information on climate change policy efforts (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 11–12).

Finally, a company is ranked at Level 4 when it develops a more strategic and comprehensive understanding of the risks and opportunities related to a low-carbon transition and incorporates this into its business strategy and capital expenditure decisions. In particular, a company is ranked at Level 4 when it does everything required in Levels 1 through 3 and takes several significant calibrated actions to address climate change. The several significant calibrated actions to address climate change include setting long-term quantitative targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, compensating senior executives who incorporate climate change performance into decision making, using scenario analysis, and making sure that trade associations that the company participates in do not take positions that are inconsistent with the company’s climate change policy (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 12).

The Transition Pathway Initiative tool ranks a company as a “four star” company when it achieves all the Transition Pathway Initiative indicators (Dietz, Jahn et al. 2019, 9). Figure 2.2 shows how indicators reveal whether a company should be ranked with as Level 0, Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, or Level 4 in addressing climate change. This is followed by a discussion on how the tool has been applied and what information it has yielded.

Use of this Transition Pathway Initiative tool has grown significantly. It is now used in a major international investment effort called Climate Action 100+ to evaluate whether companies have established long-term quantitative emissions targets and are committed to using climate scenarios in their planning (Climate Action 100+ 2019, 21, 23), and investors can encourage companies to take such action if companies are not appearing to do so. Initial analysis using the tool has revealed that there is generally a largely even spread across Level 1 through Level 4 (Dietz, Byrne et al. 2019, 11). This indicates that the majority of companies are not currently integrating carbon risk considerations into management decisions, especially with respect to recently developed Scope 3 emissions reporting and scenario analysis. However, more companies will likely receive higher level ratings as more companies integrate carbon risk considerations into management decisions, unless the Transition Pathway Initiative significantly modifies its indicators for each level.

Figure 2.2Transition Pathway Initiative Indicators and Rankings

Source: Transition Pathway Initiative

2.3 Emerging efforts

At this time, reporting on carbon risk is largely voluntary. Even in jurisdictions where reporting is mandatory, regulators do not appear to be aggressively forcing companies to report or otherwise pursuing actions against companies for failing to appropriately report information pursuant to a reporting framework. This could change in the near future, however, as the largest financial markets, the United States, Europe, and China, are moving toward mandating reporting carbon risks in standard financial disclosures. With major financial markets having mandates for reporting carbon risks in standard financial disclosures, many international companies will be required to or will simply decide to report on carbon risk in their standard financial disclosures. It is also possible that a private cause of action could develop that would allow shareholders or other parties to pursue litigation against companies that altogether fail to report carbon risks or that do so inappropriately. This could also motivate widescale disclosures.

2.3.1 United States Securities and Exchange Commission requirements

The United States Securities and Exchange Commission currently requires companies to disclose material risks pursuant to the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, but there is not clear guidance as to what extent this entails disclosing environmental risks such as climate-related risks. This could change, though. The United States House Committee on Financial Services has been passing a series of bills that lay a framework for carbon risk disclosures, but counterpart bills are not being passed in the United States Senate.

One of the most notable bills is focused on Environmental, Social, and Corporate Governance (ESG) which is a set of factors that are viewed as central in addressing sustainable and ethical corporate practices. The ESG Disclosure Simplification Act of 2019 states that ESG metrics amount to de facto material risks for the purpose of disclosures under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. Moreover, the Act requires companies to disclose in the notes section of financial filings how ESG metrics are being incorporated into business strategy (ESG Disclosure Simplification Act 2019, §2).

Another important bill is the Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2019. The Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2019 lays out specific climate change reporting requirements for a range of sectors, including the financial sector. The Act explains that companies have a duty to disclose climate-related financial risks and recommends doing so in annual reports to the Securities and Exchange Commission. According to the Act, it increases transparency to make standardized disclosures on material carbon risks that are useful to decision makers. Moreover, the Act explains that disclosures are critical in addressing climate change and help encourage a smooth transition to a low-carbon economy (Climate Risk Disclosure Act 2019, §3).

The Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2019 then seeks to develop what would arguably be the most aggressive and advanced required reporting framework anywhere in the world. It does so by first adding provisions to Section 13 of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 as Section 13(s). These provisions require companies to report on how they identify, evaluate, and manage transition and physical risks (Climate Risk Disclosure Act 2019, §5). The Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2019 then requires the Securities and Exchange Commission to issue rules identifying required disclosures under Section 13(s) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934. For example, these rules would involve reporting on Kyoto greenhouse gases and additional gases. In addition, these rules would require reporting on the specific fossil fuel securities being held. Further, these rules would involve reporting use of a 1.5 degrees Celsius scenario which reflects the large, immediate, and unprecedented global efforts necessary to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions to a level that is currently deemed desirable. Moreover, the rules would involve a discussion of short-, medium-, and long-term management strategies incorporating these metrics and other identified metrics (Climate Risk Disclosure Act 2019, §6). The Act also includes a backstop that becomes effective if the Securities and Exchange Commission does not issue rules identifying required disclosures. This backstop acknowledges that companies will be deemed in compliance with Section 13(s) of the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 if their disclosures satisfy the TCFD recommendations (Climate Risk Disclosure Act 2019, §8).

2.3.2 Additional European disclosure requirements

Since 2018, the European Union has required listed companies, banks, and insurers with more than five hundred employees to make environmental disclosures in their annual reports. This can be done using international, national, or European reporting frameworks (EU 2014; EC n.d.a). Along these lines, the European Commission has been publishing voluntary guidance on environmental disclosures companies can choose to use in order to satisfy their disclosure requirements (EC 2017a, 1, 2017b). In 2019, the European Commission also published supplemental guidelines on reporting climate-related information that it states companies can use starting in 2020 (EC 2019a, 3, 2019b). In making environmental disclosures generally and climate-related disclosures specifically, the European Commission has emphasized that disclosures be material, fair, balanced, understandable, and comprehensive but concise (EC 2017a, 3, 2017b, 2019a, 1, 2019b). A supporting document for the guidelines recognizes the TCFD recommendations as “authoritative guidance on the reporting of financially material climate-related information” and states that its new guidelines integrate the TCFD recommendations (EC 2019a, 2). As part of efforts connected with a European Green Deal, the European Commission has also launched a public consultation on disclosures (EC n.d.b).

Meanwhile, economies similar in size to France may start creating their own financial reporting frameworks, too. For instance, there have been multiple indications that mandatory disclosures are likely to be forthcoming in the United Kingdom. For instance, the Government of the United Kingdom recently published a green finance strategy, where it stated that “[t]he Government expects all listed companies and large asset owners to be disclosing in line with the TCFD recommendations by 2022” (HM Government 2019, 23). Then, only a few months later, the United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority proposed that listed United Kingdom companies will have to start disclosing their carbon risks next year. The framework for this reporting is not entirely clear, but the Financial Conduct Authority states that the expectation is for reporting to initially be done on a “comply or explain” basis (Binham and Hook 2019). This seems to be a similar strategy to that undertaken by France, allowing for the development of best practices while still pushing for disclosure.

2.3.3 Chinese disclosure requirements

For the past several years, the Chinese government has been exploring disclosure requirements. In 2017, the People’s Bank of China started collaborating on a multiyear climate and environmental disclosure pilot with the Bank of England, the City of London, and the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), which oversees its own investor-focused PRI Reporting and Assessment Framework (PBOC 2019). The Hong Kong stock exchange is requiring that exchange-listed companies, with fiscal years beginning in July 2020, prepare a statement explaining how their boards evaluate ESG risks and materiality (HKEX 2020; Temple-West and Liu 2020). Other Chinese stock exchanges are expected to follow Hong Kong’s lead, and the China Securities Regulatory Commission has announced its intention to implement broader action on this front (Temple-West and Liu 2020).

References

2 Degrees Investing Initiative. 2015. Decree Implementing Article 173-VI of the French Law for the Energy Transition. Paris: 2 Degrees Investing Initiative.

Binham, Caroline, and Leslie Hook. 2019. “Markets Watchdog Seeks to Force Companies to Disclose Climate Risk.” Financial Times, October, 16. www.ft.com/content/837eea82-f02d-11e9-ad1e-4367d8281195.

California Department of Insurance. 2018. Climate Risk Disclosure Survey Guidance Reporting Year 2018. Sacramento: California Department of Insurance.

California Department of Insurance. n.d. “NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.insurance.ca.gov/0250-insurers/0300-insurers/0100-applications/ClimateSurvey/index.cfm.

CDP. n.d.a. “CDP.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.cdp.net/en.

CDP. n.d.b. “CDP Climate Change 2020 Questionnaire.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://guidance.cdp.net/en/tags?cid=13&ctype=theme&gettags=0&idtype=ThemeID&incchild=1µsite=0&otype=Questionnaire&page=1&tgprompt=TG-124%2CTG-127%2CTG-125.

Climate Action 100+. 2019. “2019 Progress Report.”

Climate Disclosure Standards Board and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board. 2019. TCFD Implementation Guide: Using SASB Standards and the CDSB Framework to Enhance Climate-Related Financial Disclosures in Mainstream Reporting. San Francisco: Climate Disclosure Standards Board and Sustainability Accounting Standards Board.

Climate Risk Disclosure Act of 2019, H.R.3623 (2019).

Dietz, Simon, Rhoda Byrne, Dan Gardiner, Valentin Jahn, Michal Nachmany, Jolien Noels, and Rory Sullivan. 2019. TPI State of Transition Report 2019. London: Transition Pathway Initiative.

Dietz, Simon, Valentin Jahn, Michal Nachmany, Jolien Noels, and Rory Sullivan. 2019. Methodology and Indicators Report. London: Transition Pathway Initiative.

ESG Disclosure Simplification Act of 2019, H.R.4329 (2019).

European Commission. 2017a. Frequently Asked Questions: Guidelines on Disclosure of Non-Financial Information. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. 2017b. Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. 2019a. Frequently Asked Questions: Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. 2019b. Guidelines on Non-Financial Reporting: Supplement on Reporting Climate-Related Information. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. n.d.a. “Non-Financial Reporting.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/company-reporting-and-auditing/company-reporting/non-financial-reporting_en.

European Commission. n.d.b. “Non-Financial Reporting by Large Companies (Updated Rules).” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/law/better-regulation/have-your-say/initiatives/12129-Revision-of-Non-Financial-Reporting-Directive/public-consultation.

European Union, Directive 2014/95/EU (2014).

French Energy Transition Law, 2015–992 (2015).

Global Reporting Initiative. n.d. “GRI Standards.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.globalreporting.org/standards.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016a. GRI 102: General Disclosures. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016b. GRI 103: Management Approach. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016c. GRI 201: Economic Performance. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016d. GRI 302: Energy. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016e. GRI 305: Emissions. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board. 2016f. GRI 415: Public Policy. Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative and Global Sustainability Standards Board.

Global Reporting Initiative, Global Sustainability Standards Board, and CDP. 2017. Linking GRI and CDP: How Are the GRI Sustainability Reporting Standards and CDP’s 2017 Climate Change Questionnaire Aligned? Amsterdam: Global Reporting Initiative, Global Sustainability Standards Board, and CDP.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol. n.d. “Greenhouse Gas Protocol.” Accessed July 25, 2020. http://ghgprotocol.org/about-us.

Hong Kong Exchange. 2020. How to Prepare an ESG Report. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Exchange.

HM Government. 2019. Green Finance Strategy. London: HM Government.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors and Sustainable Insurance Forum. 2018. Issues Paper on Climate Change Risks to the Insurance Sector. Geneva: International Association of Insurance Supervisors and Sustainable Insurance Forum.

International Association of Insurance Supervisors and Sustainable Insurance Forum. 2020. Issues Paper on the Implementation of the Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Geneva: International Association of Insurance Supervisors and Sustainable Insurance Forum.

Mason, Amy, Will Martindale, Alyssa Heath, and Sagarika Chatterjee. 2016. French Energy Transition Law: Global Investor Briefing. London: Principles for Responsible Investment.

Messervy, Max, and Cynthia McHale. 2016. Insurer Climate Risk Disclosure Survey Report & Scorecard: 2016 Findings & Recommendations. Boston: Ceres.

Mills, Evan, Ted Lamm, Sadaf Sukhia, Ethan Elkind, and Aaron Ezroj. 2018. Trial by Fire: Managing Climate Risks Facing Insurance in the Golden State. Sacramento: California Department of Insurance.

National Association of Insurance Commissioners. n.d. “Climate Risk Disclosure.” Accessed January 10, 2019. https://content.naic.org/cipr_topics/topic_climate_risk_disclosure.htm.

People’s Bank of China, Bank of England, City of London, and Principles for Responsible Investment. 2019. UK-China Climate and Environmental Information Disclosure Pilot. Beijing: People’s Bank of China, Bank of England, City of London, and Principles for Responsible Investment.

Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. § 78a et seq (1934).

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. 2017. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. Basel: Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures.

Temple-West, Patrick, and Nian Liu. 2020. “Chinese Companies Get to Grips with Tougher ESG Disclosures.” Financial Times, January 13. www.ft.com/content/b06291aa-3251-11ea-9703-eea0cae3f0de.