4 Brown taxonomies

Because of advancements with monitoring greenhouse gases and determining their global warming potential, it has become possible to estimate how much greenhouse gas could be emitted in the atmosphere before exceeding the Paris Agreement temperature objectives, although admittedly there is significant room for disagreement on the precision of the estimates, as there are numerous factors that need to be taken into account to make such estimates. Moreover, because of these same advancements, it is possible to project how different sectors of the economy and their associated greenhouse gas emissions could achieve or fail to achieve the greenhouse gas budgets needed to meet the Paris Agreement temperature targets. Again, there could be disagreement on the precision of estimates with different sectors of the economy, too. There are also various ways that energy can be deployed to achieve the same objectives. Nevertheless, despite the risk-management challenge, this kind of analysis has provided a framework for tracking investment activities for alignment with the Paris Agreement.

4.1 Carbon bubble hypothesis

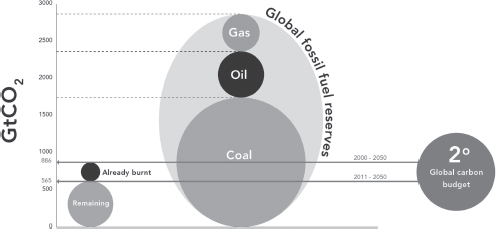

In 2011, Carbon Tracker published its report entitled Unburnable Carbon that introduced the “carbon bubble” hypothesis. This hypothesis warned about an inflating carbon bubble if more capital is invested in carbon emission–producing assets, which could crash in value. According to the carbon bubble hypothesis, the desire to restrict climate change creates a carbon budget of the amount of emissions that the world can afford. And, according to estimates, such a budget only allows for the use of a fraction of the world’s fossil fuel reserves, making the remaining vast majority of reserves unusable or stranded (Carbon Tracker 2011, 6).

Carbon Tracker explained that the Potsdam Climate Institute calculated that in order to appropriately reduce the chance of exceeding 2 degrees Celsius, there was a limit on the amount of emissions that could be released into the atmosphere between 2000 and 2050. Even less could be emitted if it was desired to limit temperature increases to 1.5 degrees Celsius. At the same time, using corresponding emissions factors for coal, oil, and gas, the Potsdam Climate Institute calculated the total foreseeable emissions from burning the earth’s identified coal, oil, and gas reserves. This revealed that burning all of these reserves would result in carbon being released into the atmosphere far in excess of the amount of emissions that could be released into the atmosphere while still likely achieving 2 degrees Celsius or lower targets by 2050. According to Carbon Tracker, at most, one-fifth of the Earth’s reserves could be used by 2050 if the world wanted to reduce the chance of exceeding 2 degrees Celsius to twenty percent (Carbon Tracker 2011, 6). Figure 4.1 details the carbon bubble hypothesis.

Both international environmental and financial regulators have acknowledged the credibility of the carbon bubble hypothesis. Similar to Carbon Tracker, the IPCC concluded that in order to limit global temperature rise to 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels, only between one-fifth and one-third of the world’s proven oil, gas, and coal reserves could be burned (Carney 2015; IPCC 2014; Hill and Martinez-Diaz 2019, 56–58). Governor Carney referenced the carbon bubble hypothesis in his Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon speech. He said that financial markets were not appropriately valuing fossil fuel assets and other assets tied to them. As Governor Carney explained, the desire to restrict climate change creates a carbon “budget” of the amount of emissions that the world can “afford.” And, according to estimates, such a budget only allows for the use of a fraction of the world’s fossil fuel reserves, making the remaining vast majority of reserves unusable or “stranded” (Carney 2015). However, assets tied to these reserves are being valued as if all the reserves can be used. A quick realization that these reserves are unburnable and therefore in fact stranded could lead to a market shock, that is, what some have equated to the bursting of a “carbon bubble” (Carney 2015; Carney, Villeroy de Galhau, and Elderson 2019). The Dutch Bank also discussed the carbon bubble hypothesis in a comprehensive climate report (Regelink et al. 2017, 12). While there is debate over how significant of an impact a reevaluation of carbon assets could have and what assets in particular are most at risk of becoming stranded in a transition to a low-carbon economy (Carbon Tracker 2019), it is becoming generally accepted within the global financial community that certain assets may become stranded without significant advancements in carbon storage or other technologies limiting emissions from the burning of fossil fuels.

Figure 4.1Carbon Bubble Hypothesis

Source: Carbon Tracker. This image was viewable on July 25, 2020 on the Carbon Tracker website: www.carbontracker.org/reports/carbon-bubble/

In fact, shifts in the global economy are already observable. In the last several years, coal has experienced major losses. The Dow Jones United States Coal Index decreased over ninety percent in value from April 2011 to June 2017 (S&P Global n.d.). Dozens of coal companies filed for bankruptcy between 2012 and 2015 (Kuykendall 2015). In the United States, the percentage of electricity generated from coal has dropped significantly (Levisohn 2017), and coal production has plummeted (Krauss 2016). In 2020, for the first time, coal will likely have produced less electricity in the United States than renewable energy (Plumer 2020). Moreover, major banks are refusing to invest in new coal infrastructure (Buckley 2019), and major insurance companies are restricting underwriting for coal infrastructure (AXA 2020, 30). Financial support in Asia may even be stemmed, with Japan’s environment minister vowing to slash financing that has supported construction of coal infrastructure in India, Vietnam, and Indonesia (Harding 2020).

Other fossil fuel assets also appear likely to face challenges in the near future. Major economies, such as the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, California, China, and Singapore, are planning to ban the sale of gasoline and diesel-powered vehicles in the coming decades (Petroff 2017; Newsom 2020; BBC 2017; Aravindan and Geddie 2020). Shareholders are suing oil companies over their failure to disclose their knowledge on the connection between climate change and their business operations (Savage 2019). Oil prices have dropped to historic lows during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gladstone 2020), and while prices are likely to rebound, the price drop has clearly revealed the asset’s volatility. Utilities are also facing mounting infrastructure challenges that they themselves are attributing to climate change (Brody, Rogers, and Siccardo 2019).

To help ensure a smooth transition to a low-carbon economy, Governor Carney and other leading financial thinkers believe that it is important to divest from, engage with, or at least monitor assets that could potentially become stranded. Along the same lines, to replace lost energy production, there needs to be more investment in sustainable or green energy. Indeed, there have been a number of efforts to track specific equity and fixed income investments to determine whether they are connecting with sectors of the economy in a manner that would ensure achievement of sustainability ambitions, such as the Paris Agreement objectives.

4.2 Classifications

As fossil fuel assets could potentially become stranded, the financial community is increasingly monitoring these assets and in some cases is encouraging either divestment or engagement as a means of addressing carbon risk. To do so the government and nonprofit organizations have developed classification systems for identifying fossil fuel investments which can be viewed as brown taxonomies or precursors to such if the government or nonprofit organizations managing them do not formally or informally view them as brown taxonomies. The development and application of these classification systems has been made possible through already established financial practices for labeling securities with unique numerical identifiers (CUSIP Global Services n.d.; ISIN Organization n.d.). These unique numerical identifiers reflect the issuer of securities and whether they are debt or equity. The numerical identifiers have also allowed third-party data product providers to sell data products that can provide additional information for specific numerical identifies, including information on the sectors, industry groups, and subindustry groups that specific securities fit into (MSCI n.d.). There are now also third-party data providers, such as Trucost, that provide information on the percentage of revenue that companies are generating from fossil fuel enterprises and the percentage of electricity that utilities are generating from fossil fuel sources. Together, the numerical identifiers and third-party data products can be used to run an automated analysis across an investment portfolio to quickly identify the prevalence of fossil fuel investments.

Monitoring greenhouse gas emissions is helpful in informing a company how to act in reducing its own emissions. However, there are challenges when aggregating this information across an investment portfolio or communicating specific actions that can be taken to decision makers based solely on this information. Tracking investments using security information, on the other hand, either in combination with or separately from greenhouse gas emissions, allows for easier aggregation of data and more specific guidance that can more easily be communicated for investment decisions.

4.2.1 California pension funds

California has been a leader in advocating for divestment from what is believed to be one of the assets most as risk of becoming stranded: thermal coal. This is the type of coal that is burned to generate electricity rather than metallurgic coal that is used to make steel. As it is generally accepted that coal power plants will have to be retired in order to meet global emissions targets (Yanguas et al. 2019), and coal plants are now closing as countries such as the United Kingdom, France, the Netherlands, and Germany move forward with phasing out coal power (Johnson 2020; Reuters 2019; Netherlands 2019; BBC 2020), there is a decreasing need for this fuel source under most future energy projections.

California’s initial push to limit investment in thermal coal was through state legislation signed into law by Governor Jerry Brown in 2015. This legislation directed the state’s two largest pension funds, the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), managing over three hundred billion dollars in assets (CalPERS n.d.), and the California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), managing over two hundred billion dollars in assets (CalSTRS 2020), to completely divest from thermal coal companies and not make future investments in those companies unless the companies showed that they were transitioning to a clean-energy future (Public Divestiture of Thermal Coal Companies 2015). The legislation, however, did not require the CalPERS and CalSTRS boards to take any action unless the boards determined in good faith that such action was consistent with the board’s fiduciary responsibilities (Public Divestiture of Thermal Coal Companies 2015, §1).

The state legislation added a section to California’s Government Code, reading in part:

Thermal coal companies were identified as those companies that derive fifty percent or more of their revenue from the mining of thermal coal (Public Divestiture of Thermal Coal Companies 2015, §1). This pension fund classification system, which has a fairly straightforward coal classification, is detailed Table 4.1. This is followed by a discussion on how both the CalPERS and CalSTRS boards acted with respect to this classification.

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Thermal Coal Enterprises – Percentage | Companies that derive fifty percent or more of their revenue from the mining thermal coal |

Both the CalPERS and CalSTRS boards subsequently found that divestment was consistent with their fiduciary duties and voted to take such action. The CalPERS investment committee made its decision to divest in closed session. Although minutes are not available for that session, agenda materials are available and reveal actions taken by staff. These materials show that staff engaged seventeen coal companies. Fourteen offered no transition plan away from coal, and three offered a transition plan to a cleaner energy model. The CalPERS investment committee decided to remain invested with the three companies that offered a transition plan and divested from those that did not (CalPERS 2017, 3).

The CalSTRS board publicly voted to divest from thermal coal companies (CalSTRS 2017). Board members made the following statements when doing so. California State Controller Betty Yee stated:

California State Treasurer John Chiang further stated:

CalPERS ultimately divested approximately fourteen million dollars from thermal coal assets (CalPERS 2017, 3), and CalSTRS ultimately divested approximately ten million dollars from thermal coal assets (CalSTRS 2017). Both amounts were relatively small, with a total of over five hundred billion dollars that they collectively manage, most of that being publicly traded stock (CalPERS 2020; CalSTRS 2020). The California pension fund effort mirrors similar efforts taken by smaller government pension funds elsewhere in the United States and Europe. Nordic countries such as the Norwegian Government Pension Fund were the first to divest, with guidance from a European-based NGO with divestment expertise, Urgewald (n.d.b).

4.2.2 Climate Risk Carbon Initiative

A second push for thermal coal divestment came from California’s insurance regulator, the California Department of Insurance. Unlike elsewhere in the world, insurance is regulated at the subnational level in the United States (McCarran-Ferguson Act 1945). This provides larger states with unique regulatory authority akin to countries in other parts of the world. The California Department of Insurance, as the largest insurance regulator in the United States and one of the largest in the world, asked all insurance companies operating in California to voluntarily divest from thermal coal. In doing so, then California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones wrote to insurance companies stating the following in an effort he described as the California Department of Insurance’s Climate Risk Carbon Initiative:

Moreover, then-Commissioner Jones asked all insurance companies to answer questions on any plans to divest from thermal coal and asked larger insurance companies to disclose a list of their fossil fuel investments (Jones 2016). Guidance for disclosing fossil fuel investments explained that the fossil fuel investments that should be disclosed included any investments meeting the following criteria: investments in companies generating over thirty percent of their revenue from thermal coal, investments in utilities generating over thirty percent of their electricity from the burning of thermal coal, investments in companies generating over fifty percent of their revenue from oil and gas combined, and investments in utilities generating over fifty percent of their electricity from the burning of coal, oil, and gas combined (CDI 2016, 4, 7–8). Table 4.2 details the classification system.

Using responses from over six hundred of the largest insurance companies operating in California and supplemental data provided by a consultant, the California Department of Insurance built a searchable database of fossil fuel investments being held by all insurance companies operating in California. The database can be searched for a specific company, the total assets that the company has under management, the amount of those assets that are thermal coal or other fossil fuel investments, and whether the company has any plans to divest from thermal coal. Clicking on certain categories also provides more detailed information, such as information on the types of investments being held and the names of those investments. Queries can also be run that reveal outliers, such as those companies holding the greatest amount of categorized thermal coal investments. Certain companies have much larger concentrations of such assets than other companies (CDI n.d.).

The California Department of Insurance has continued to supplement its database. However, in subsequent years, the Department worked with a consultant to obtain all financial data from annual filings rather than seeking responses from the largest insurance companies operating in California and supplementing that data. Information for subsequent years can be accessed through the same searchable database by selecting the year for which data is desired (CDI n.d.).

The California Department of Insurance also provides aggregate fossil fuel numbers and charts comparing annual data. This data reveals that insurers doing business in California have over five hundred billion dollars, or approximately eleven percent, of their assets under management invested in fossil fuels. Of this over five hundred billion dollars, over a hundred billion is invested in thermal coal. The majority is in utility investments. The minority, approximately twenty-one billion dollars, is invested in thermal coal enterprises (CDI n.d.).

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Thermal Coal Enterprises – Percentage | Companies that derive over thirty percent of their revenue from thermal coal |

| Utility Coal Power Generation | Utilities that generate over thirty percent of their electricity from burning thermal coal |

| Fossil Fuel Enterprises Excluding Coal – Percentage | Companies that derive over fifty percent of their revenue from oil and gas combined |

| Utility Fossil Fuel Power Generation | Utilities that generate over fifty percent of their electricity from burning thermal coal, oil, and gas combined |

The amount of total fossil fuel investments and thermal coal investments has stayed relatively flat across the years analyzed by the Department (CDI n.d.). Nevertheless, there is reason to believe that divestment is taking place. To begin with, this is because the price of these assets has increased slightly since former Commissioner Jones first called for divestment. For several years, the Dow Jones United States Coal Index decreased dramatically, but then increased slightly (S&P Global n.d.). Following a dramatic price decrease, the slight price increase could make the aggregate coal numbers look similar across years even if less of that asset is being held in subsequent years. Moreover, another reason to believe that divestment is taking place is because a supplemental survey conducted in 2018 showed that the number of insurers divesting from thermal coal has increased since the initial call for divestment and the survey conducted in connection with that call (CDI 2018).

4.2.3 Global Coal Exit List

On their own, companies are also moving forward with divesting from thermal coal, asserting both financial and environmental reasoning. While some of these companies originally classified thermal coal the same as or similar to the classifications used by the California Department of Insurance, some of these companies have since expanded that classification to also include companies that generate significant revenue from coal in the aggregate and utilities that are expanding their ability to generate electricity from the burning of thermal coal. Major international companies are reporting thermal coal divestment in their TCFD and French Energy Transition Law reports. Divestment classifications are becoming more aggressive, too. For instance, in a TCFD and French Energy Transition Law–aligned report, one of the world’s largest insurers, AXA, explained its thermal coal divestment strategy as follows.

AXA then explained that in 2017, it decided to increase its thermal coal divestment to reach billions of dollars by expanding its coal exclusion criteria by several means. To begin with, the criteria were expanded to include enterprises deriving over thirty percent of their revenues from coal and utilities generating over thirty percent of their electricity from the burning of coal, which is more inclusive than its original fifty percent thresholds. According to AXA, this captures long-term financial risks related to “stranded assets.” Further, AXA expanded its coal exclusion criteria to include companies with significant coal-based power “expansion plans.” According to AXA, such companies are constructing new coal power plants that are locking economies into coal power for decades, which clearly contradicts the Paris Agreement. Moreover, AXA expanded its coal exclusion criteria to include mining companies that annually produce large quantities of coal (AXA 2018, 15–16). AXA has continued to expand its coal criteria (AXA 2020, 26, 30).

Some companies that are divesting from coal may hire their own consultants to identify coal securities in their investment portfolios. At least some companies that are divesting from thermal coal use the Global Coal Exit List, though, or related resources to identify thermal coal investments, including AXA and other major reinsurers such as Swiss Re and Zurich (Urgewald n.d.b). The Global Coal Exit List, constructed by Urgewald, contains hundreds of companies identified as being connected with the coal industry. Along with information identifying each company and some background information on that company’s activities if they are in the power sector, there is data corresponding to categories of activities that asset owners can use to identify a company as a coal investment. These categories include the revenue and power thresholds used by the California Department of Insurance to identify thermal coal, companies with over thirty percent of their revenue derived from coal, and utilities generating over thirty percent of their electricity from coal. The categories also include aggregate numbers, such as coal companies producing large quantities of coal and utilities with the capacity to generate large amounts of electricity from burning coal. There is also information on companies expanding their thermal coal activities. This includes companies significantly expanding their thermal coal mining or infrastructure development and utilities that are planning substantial increases in their capacity to generate electricity from coal, for example, by over three hundred megawatts (Urgewald n.d.a). Table 4.3 details the classification system.

Urgewald hosts a public version of its Global Coal Exit List on its website. Asset owners can also obtain a list with security identification numbers from Urgewald. This will further facilitate matching securities within asset owners’ portfolios with thermal coal designations in case the asset owner has difficult identifying securities from the companies identified in the public version of the Global Coal Exit List (Urgewald n.d.a).

| Classification | Description |

|---|---|

| Thermal Coal Enterprises – Percentage | Companies that derive a certain percentage of their revenue from thermal coal |

| Utility Coal Power Generation – Percentage | Utilities that generate a certain percentage of their electricity from burning thermal coal |

| Thermal Coal Enterprise – Aggregate | Companies that derive a certain amount of revenue from thermal coal |

| Utility Coal Power Generation – Aggregate | Utilities that generate a certain amount of electricity from burning thermal coal |

| Thermal Coal Expansion | Companies significantly expanding their thermal coal mining or infrastructure development and utilities that are planning substantial increases in their capacity to generate electricity from coal |

4.2.4 Additional taxonomies

In addition to divesting from thermal coal assets, there are also efforts to divest from or otherwise restrict investments in specific subset of oil assets, tar, or oil sands. Oil sands potentially pose unique regulatory and environmental risks that could impact their price in the long run. Depending on reserves and processing capabilities, they may also be more expensive to extract and refine than other oil sources, making them more exposed to price decreases. For example, the San Francisco State University Foundation, which manages the university’s endowment, voted to make no new investments in “direct ownership of companies with significant exposure to production or use of coal and tar sands” (Examiner Staff 2014). A number of companies have also stated that they will divest from and no longer invest in oil sands. In its TCFD and French Energy Transition Law–aligned report, in addition to explaining its coal divestment strategy, AXA explained its oils sands divestment strategy. This included divesting from the main oil sands producers, which it defined as producers with at least thirty percent of their reserves relying on oil sands, and from the primary companies involved with the development of oil sands pipelines. AXA explained that it was taking these steps because oil sands are “an extremely carbon-intensive form of energy and a serious cause of local environmental pollution” (AXA 2018, 16). AXA credits its coal and oils sands divestment with brining its investment portfolio more in line with the Paris Agreement (AXA 2020, 19).

In addition to targeted coal and oils sands divestment efforts, there are also increased efforts to divest from or restrict investment in fossil fuel assets more generally. In 2019, citing “financial risk,” the University of California system stated that it would no longer invest in fossil fuel assets. The classifications that the University of California will use to identify what constitutes a fossil fuel asset are not entirely clear (Mello 2019). Presumably, further fossil fuel restrictions could include refraining from investments in those assets that the University of California has already divested from, other types of fossil fuels, or expanded definitions of thermal coal and oil sands. The University of California previously divested from both coal and oil sands (Mello 2019).

While companies themselves as asset managers continue to divest from fossil fuel assets, some government entities are also asserting that they will not hire companies invested in or doing business with certain fossil fuel industries. For instance, in 2018, the Paris City Council passed a motion asking insurers to stop any support for the coal industry (Insurance Business 2018; Resolution Urging Coal Divestment 2018; Paris City Council Motion 2018). Later that year, the City and County of San Francisco took the position that it would also no longer do business with insurers that are invested in specific fossil fuel–related assets, in particular coal and oil sands, or underwriting their operations. The City and County of San Francisco Board of Supervisors passed a resolution urging the City and County of San Francisco to screen potential insurers for thermal coal and oil sands investments and to end any formal relationship with insurers that are not taking steps toward full divestment from thermal coal and oil sands (Resolution Urging Coal Divestment 2018). The classifications that the City and County of San Francisco Board of Supervisors will use to identify thermal coal and oil sands have not currently been released publicly.

4.2.5 Comparing classifications

With continued efforts to monitor assets that could potentially become stranded, there have been increasing divergences in what constitutes fossil fuel assets. Some of these divergences are observable, for instance, on the face of the classifications for the three efforts that were previously discussed: the California pension fund classification, the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications, and the Global Coal Exit List classifications. The California pension fund classification, the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications, and the Global Coal Exit List classifications all assert they are tracking coal. However, each effort defines what constitutes a coal asset slightly differently.

Both the California pension fund and Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications specifically apply to thermal coal and exclude metallurgic coal. In principle, the Global Coal Exit List follows the same approach. However, if companies do not differentiate between revenue generated from thermal coal and metallurgic coal, the Global Coal Exit List calculates the total coal share of revenue. While a classification system including all coal is presumably more inclusive, it is unclear how many companies would fit into a classification system tracking all coal and not one tracking simply thermal coal. That may also depend on what business activities the classification system tracks and what threshold percentage is applied.

The California pension fund classification specifically states that it applies to mining operations. The Climate Risk Carbon Initiative and the Global Coal Exit List do not just track mining operations. They also track other upstream and downstream activities. Other upstream activities include coal exploration and the development of coal mines. Downstream activities include the transportation, trading, and burning of coal.

The California pension fund classification includes companies generating at least fifty percent of their revenue from thermal coal. The Climate Risk Carbon Initiative and the Global Coal Exit List instead look at where revenue is at least thirty percent. The latter presumably includes a more extensive list of companies. Also, the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative and the Global Coal Exit List track all coal-related business activities. There may, however, be variation between the lists with regard to how much business activity is being generating from these lines of activities, for instance, where a mixed mining operation is mining different types of metals, an equipment manufacturer is providing equipment to different types of business activities, or a transportation company is moving various goods. Such distinctions may depend on available data and could change over time.

The Global Coal Exit List tracks mining operations that produce large quantities of coal. For instance, this could include large international companies with various lines of business, one of which is significant coal mining, even where coal is not responsible for thirty percent or more of revenue. The California pension fund and the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications do not specifically track this.

Both the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative and Global Coal Exit List classifications include utilities that generate thirty percent or more of their electricity from the burning of thermal coal. The California pension fund classification does not track utilities, however. The California pension fund classification only looks at the mining of thermal coal.

The Global Coal Exit List tracks utilities that generate a large amount of electricity from coal. For instance, this could include large utilities that do not generate nearly thirty percent of their electricity from coal because they rely on a diversified energy mix, but they nonetheless still generate a significant aggregate amount of electricity from the burning of thermal coal. The California pension fund and the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications do not specifically track this.

The Global Coal Exit List tracks utilities that are building new coal power plant facilities. The California pension fund and the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative classifications do not track this. It is unclear to what extent this classification draws in additional companies. It may depend on the global reach of covered investments, because the limited coal power development taking place is primarily located in Asia.

There are also differences among efforts to track other types of fossil fuel assets. For instance, the Climate Risk Carbon Initiative uses a threshold approach for tracking other fossil fuel assets that is similar to how the Initiative tracks thermal coal assets, with revenue and power generation thresholds. However, other efforts that are still developing are specifically targeting oil sands. The classifications for determining what companies constitute oil sands companies are still unclear, but there will likely be divergences, as has been seen with coal, if targeting this asset becomes more widely accepted.

As discussed previously with respect to coal, aggregate classifications for enterprises and utilities are not always used in systems for monitoring assets that could potentially become stranded. They are also not necessarily explained as incorporated, because they are viewed as identifying at-risk investments. Quantification systems exist for oil and gas but are not as widely adopted as those for coal. When oil and gas are included, they are sometimes a subset of assets such as oil sands. The California Department of Insurance, for instance, applied a threshold classification to oil and gas. Reinsurers and the City and County of San Francisco have specifically identified oil sands.

There seems to be the most agreement in classifying most upstream fossil fuel enterprises, such as extraction, production, and transportation of fossil fuels, as brown assets. However, even within this area, there are contentions about specific companies. Some classifications, such as those used by California pensions, are narrow. They only include companies’ mining operations or those generating over fifty percent of their revenue from thermal coal.

When applying only threshold classifications, it can also be difficult to classify companies that are involved in a range of activities. This includes certain companies transporting various goods or manufacturing equipment for a range of activities, not just fossil fuel enterprises. Also, categorizing fossil fuel enterprises as a specific type, such as thermal coal, can also be difficult when there are companies that operate mixed mining facilities or the raw materials could be used for separate activities, such as the production of steel rather than the generation of electricity.

There is disagreement in classifying utilities at fossil fuel companies that extends beyond the distinctions discussed previously. The two most established databases, California’s Climate Risk Carbon Initiative database and the Global Coal Exit List, both recognize utilities as fossil fuel companies, although both identify that as one particular classification among several for identifying fossil fuel assets. Alternatively, some rating agencies include energy mix as one particular classification among several in categorizing a utility as at risk. However, they also view other factors, such as market position and local regulator policies, as important in understanding at-risk conditions. There is the thinking that some facilities have the ability to transfer away from the burning of coal, so in one year, they could be labeled thermal coal, and that labeling would not necessarily be appropriate in the following year. For example, Moody’s has incorporated energy mix as part of the rating criteria for regulated electric and gas utilities. In particular, the rating looks at generation and fuel diversity. Utilities with lower exposure to penalties and taxes typically connected with the fossil fuel industry are typically rated higher. However, the generation and fuel diversity factor only composes five percent of a utility’s rating (Moody’s 2017, 33). A number of other factors are weighted more heavily (Moody’s 2017, 4).

With efforts to monitor fossil fuel assets, there are additional challenges that present themselves. To begin with, the organizational structure of a company is not always clear. This can become an issue when applying threshold classifications that may not identify a parent company as a fossil fuel asset but instead identify a subsidiary company. To address this concern, the California Department of Insurance issued specific guidance indicating that its efforts applied to all companies, regardless of their status as a parent or subsidiary (CDI 2016, 5). The Global Coal Exit List also specifically states that it includes both parent and subsidiary companies, listing information for both (Urgewald n.d.a).

It is difficult to identify the investment holdings of specific companies from publicly available information. In many countries, companies are not required to publicly release their investment holdings. Even in those countries where certain companies are required to publicly release this information, such as the United States, it is still not easy to identify all investment holdings. For instance, it is not easy to identify private placement information that is not publicly traded with corresponding security identification numbers. At a minimum, private placement information needs to be culled manually from disclosures and cannot simply be uploaded along with information for publicly traded investment holdings.

Threshold information is proprietary. With respect to revenue, companies may take issue with how they are being classified, but it would be difficult for them to identify a concern, because it may not be clear to them how they are being categorized and how such a distinction is being made. With respect to power generation, there is not even a readily available public list of how all utilities are generating their electricity.

Tracking divestment of specific types of assets is extremely difficult. It is not difficult to observe the total aggregate amount. However, aggregate amounts can fluctuate based on the price of the assets rather than the amount of securities being held. Moreover, a company could report divesting from one fossil fuel security only to purchase another fossil fuel security.

In addition to how monitoring is conducted, there are multiple means to address concerns with assets at risk of becoming stranded assets. While some companies believe that divestment is the best means for addressing concerns with at-risk assets, other entities believe that, at least in certain circumstances, it is more appropriate to engage companies rather than simply divest from them. This make sense, for instance, in circumstances where a current stock position makes it difficult to currently divest without suffering significant losses or where a company investee is positioned in such a manner that it could modify its business operations to address the factors that make the company an at-risk asset. While smaller investors may be unable to exert necessary influence on a company investee, a larger investor may be able to do so.

As two of the world’s largest pension funds and asset holders, CalPERS and CalSTRS have significant influence on impacting market behaviors. As seen simply with its coal effort, CalPERS reached out to seventeen companies asking that they divest from thermal coal if the company wished for CalPERS to remain invested in it. While it is unclear to what extent these outreach efforts impacted the investee companies’ decision making, three of the companies that CalPERS engaged provided a plan to transition away from thermal coal (CalPERS 2017, 3). CalPERS is also now leading a larger corporate engagement strategy known as Climate Action 100+ where it and other large asset holders are asking investee companies to address climate change on an even more robust scale.

The NGFS explained that it is important to have clear standards for monitoring investments at risk of becoming stranded, such as investments in fossil fuel companies. Such standards, which the NGFS hinted at as a “brown” taxonomy, could help identify the assets that will be impacted by the Paris Agreement and a transition to a low-carbon economy (NGFS 2019, 35). A recent publication by the Bank of International Settlements and Bank of France also discussed the idea of a brown penalizing factor that would increase capital requirements where there is greater exposure to investments at risk of becoming stranded (Bolton et al. 2020, 52). At this time, however, financial regulators have not collectively endorsed such a taxonomy or a penalizing factor.

References

Aravindan, Aradhana, and John Geddie. 2020. “Singapore Aims to Phase Out Petrol and Diesel Vehicles by 2040.” Reuters, February 18. www.reuters.com/article/us-singapore-economy-budget-autos/singapore-aims-to-phase-out-petrol-and-diesel-vehicles-by-2040-idUSKBN20C15D.

AXA. 2018. Climate-Related Investment & Insurance Report. Paris: AXA.

AXA. 2020. 2020 Climate Report: Renewed Action in a Time of Crisis. Paris: AXA.

Bolton, Patrick, Morgan Despres, Luiz Awazu Pereira da Silva, Frédéric Samama, and Romain Svartzman. 2020. The Green Swan: Central Banking and Financial Stability in the Age of Climate Change. Basel: Bank of International Settlements and Bank of France.

British Broadcasting Corporation. 2017. “China Looks at Plans to Ban Petrol and Diesel Cars.” British Broadcasting Corporation, September 10. www.bbc.com/news/business-41218243.

British Broadcasting Corporation. 2020. “Germany Agrees Plan to Phase Out Coal Power by 2038.” British Broadcasting Corporation, January 16. www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-51133534#:~:text=The%20German%20government%20and%20regional,depending%20on%20the%20progress%20made.

Brody, Sarah, Matt Rogers, and Giulia Siccardo. 2019. “Why, And How, Utilities Should Start to Manage Climate-Change Risk.” McKinsey & Company Electric Power & Natural Gas, April. www.mckinsey.com/industries/electric-power-and-natural-gas/our-insights/why-and-how-utilities-should-start-to-manage-climate-change-risk#.

Buckley, Tim. 2019. Over 100 Global Financial Institutions Are Exiting Coal, With More to Come. Cleveland: Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

California Department of Insurance. 2016. Climate Risk Carbon Initiative Questions & Answers. Sacramento: California Department of Insurance.

California Department of Insurance. 2018. Survey Results of Insurer Investments Tied to Thermal Coal Released. Sacramento: California Department of Insurance.

California Department of Insurance. n.d. “Climate Risk Carbon Initiative.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://interactive.web.insurance.ca.gov/apex_extprd/f?p=250:1:0.

California Public Employees’ Retirement System. 2017. Public Divestiture of Thermal Coal Companies Act Report to the California Legislature and Governor. Sacramento: California Public Employees’ Retirement System.

California Public Employees’ Retirement System. n.d. “Investments.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.calpers.ca.gov/page/investments.

California State Teachers’ Retirement System. 2017. “CalSTRS Takes Action to Divest of All Non-U.S. Thermal Coal Holdings.” Modified, June 7. www.calstrs.com/news-release/calstrs-takes-action-divest-all-non-us-thermal-coal-holdings.

California State Teachers’ Retirement System. n.d. “Investments Overview.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.calstrs.com/investments-overview.

Carbon Tracker. 2011. Unburnable Carbon – Are the World’s Financial Markets Carrying a Carbon Bubble? London: Carbon Tracker.

Carbon Tracker. 2019. Balancing the Budget: Why Deflating the Carbon Bubble Requires Oil & Gas Companies to Shrink. London: Carbon Tracker.

Carney, Mark. 2015. “Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – Climate Change and Financial Stability.” Speech at Lloyd’s of London, London, September.

Carney, Mark, Francois Villeroy de Galhau, and Frank Elderson. 2019. Open Letter on Climate-Related Financial Risks. London: Bank of England.

CUSIP Global Services. n.d. “CUSIP Global Services.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.cusip.com.

Examiner Staff. 2014. “SF State Joins Campaign to Divest Money from Fossil Fuels.” San Francisco Examiner, April 8. www.sfexaminer.com/news/sf-state-joins-campaign-to-divest-money-from-fossil-fuels/?oid=2757805.

Gladstone, Rick. 2020. “Oil Collapse and Covid-19 Create Toxic Geopolitical Stew.” The New York Times, April 22. www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/world/middleeast/oil-price-collapse-coronavirus.html.

Government of the Netherlands. 2019. Climate Agreement. The Hague: Government of the Netherlands.

Harding, Robin. 2020. “Japan Vows to Slash Financing of Coal Power in Developing World.” Financial Times, July 12. www.ft.com/content/482fa9e4-5eb5-4c61-a777-998993febae0.

Hill, Alice C., and Leonardo Martinez-Diaz. 2019. Building a Resilient Tomorrow, How to Prepare for the Coming Climate Disruption. New York: Oxford University Press.

Insurance Business. 2018. “Paris City Council Calls on Insurers to Ditch Coal.” Insurance Business, May 3. www.insurancebusinessmag.com/uk/news/breaking-news/paris-city-council-calls-on-insurers-to-ditch-coal-99578.aspx.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

ISIN Organization. n.d. “ISIN Organization.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.isin.org.

Johnson, Boris. 2020. “PM Speech at COP 26 Launch.” Speech at Prime Minister’s Office, London, February.

Jones, Dave. 2016. Coal Divestment & Carbon-Based Investment Data Call. Sacramento: California Department of Insurance.

Krauss, Clifford. 2016. “Coal Production Plummets to Lowest Level in 35 Years.” The New York Times, June 10. www.nytimes.com/2016/06/11/business/energy-environment/coal-production-decline.html.

Kuykendall, Taylor. 2015. “Roster of United States Coal Companies Turning to Bankruptcy Continues to Swell.” SNL Energy, June 4. www.snl.com/InteractiveX/Article.aspx?cdid=A-32872208-12845.

Levisohn, Ben. 2017. “Why Paris Pullout Is No Cure All for Coal.” Barron’s, June 6. www.barrons.com/articles/why-paris-pullout-is-no-cure-all-for-coal-1496762504.

McCarran-Ferguson Act of 1945, 15 U.S.C. §§ 1011–1015 (1945).

Mello, Felicia. 2019. “Citing ‘Financial Risk,’ University of California Pledges to Divest from Fossil Fuels.” Cal Matters, September 17. https://calmatters.org/education/higher-education/2019/09/uc-divests-fossil-fuels-citing-finance-renewable-energy-climate-change/.

Moody’s Investors Service. 2017. Regulated Electric and Gas Utilities. New York: Moody’s.

MSCI. n.d. “The Global Industry Classification Standard.” Accessed July 25, 2020. www.msci.com/gics.

Network for Greening the Financial System. 2019. A Call for Action, Climate Change as a Source of Financial Risk. Paris: Network for Greening the Financial System.

Newsom, Gavin. Executive Order N-79-20 (2020).

Paris City Council Motion. 2018.

Petroff, Alanna. 2017. “These Countries Want to Ditch Gas and Diesel Cars.” CNN Business, July 26. https://money.cnn.com/2017/07/26/autos/countries-that-are-banning-gas-cars-for-electric/.

Plumer, Brad. 2020. “In a First, Renewable Energy Is Poised to Eclipse Coal in U.S.” The New York Times, May 13. www.nytimes.com/2020/05/13/climate/coronavirus-coal-electricity-renewables.html.

Public Retirement Systems: Public Divestiture of Thermal Coal Companies, S.B.185 (2015).

Regelink, Martjin, Henk Jan Reinders, Maarten Vleeschhouwer, and Iris van de Wiel. 2017. Waterproof? An Exploration of Climate-related Risks for the Dutch Financial Sector. Amsterdam: Dutch Bank.

Resolution Urging Insurance Industry Companies to Divest from Coal and Tar Sands Industries; And to End the Underwriting of Activities in Furtherance of the Extraction or Use of Coal and Tar Sands, Resolution No. 273–18 (2018).

Reuters. 2019. “France’s EDF to Close Le Havre Coal-Fired Power Plant in Spring 2021.” Reuters, June 7. www.reuters.com/article/france-electricity-coal/frances-edf-to-close-le-havre-coal-fired-power-plant-in-spring-2021-idUSL8N23E254.

Savage, Karen. 2019. “Shareholders Sue Exxon for Misrepresenting Climate Risks.” Climate Liability News, August 7. www.climateliabilitynews.org/2019/08/07/exxon-shareholders-climate-risks-lawsuit/.

S&P Global. n.d. “Dow Jones U.S. Coal Index.” Accessed 2020. www.spglobal.com/spdji/en/indices/equity/dow-jones-us-coal-index/#overview.

Urgewald. n.d.a. “Global Coal Exit List.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://coalexit.org.

Urgewald. n.d.b. “Urgewald.” Accessed July 25, 2020. https://urgewald.org/english.

Yanguas, Paolo A., Gaurav Ganti, Robert Brecha, Bill Hare, Michiel Schaeffer, and Ursula Fuentes. 2019. Global and Regional Coal Phase-Out Requirements of the Paris Agreement: Insights from the IPCC Special Report on 1.5°C. Berlin: Climate Analytics.