Chapter 02

Stage 7 in use

Stage 7

In use

CHAPTER 02

Overview

This chapter is about Stage 7 In Use, which can be both the first stage in a potential project or the final stage in an existing project and is when:

- An existing project is reviewed to improve use or review ongoing viability.

- A building (or buildings) are reviewed to inform a subsequent Stage 0 for a potential new project.

The key purpose of this stage is to understand how well a building performs in use. It might also be to assess how well it met desired outcomes that established it as a project – and to learn and inform future projects of a similar, or related, nature.

This chapter explains how Stage 7 links the circular process of the Plan of Work 2013, and is both the start and end of this circular process.

The chapter sets out the different issues to consider in undertaking an In Use review of a project. Stage 7 is entirely about diagnosis and review; there are no design activities or tasks involved in it.

What is Stage 7 in Use?

Stage 7 In Use is a renewed and substantially expanded stage in the Plan of Work 2013. It is unique in that it can be both the first and last stage of a project, depending on how it is used, completing the circular process of planning, designing, constructing and use over time. Stage 7 is the organised study and analysis of a building in use, and includes all aspects of that building and the uses taking place within it.

At the end of Stage 5, the project moves toward independent life. At Stage 6, handover is completed and the client and users live and work with it. Stage 7 In Use is when clients and users, and project teams, discover:

- How well the building supports the needs and desires of all its stakeholders.

- How easy and sustainable it is to operate, maintain and understand.

- Specifically, how well it accommodates the requirements of an organisation or, for example, the lifestyle of a family.

These are the true measure of the success of all the preceding stages, 0 to 6 inclusive – yet historically, and still all too commonly today, project teams are not engaged to return to projects post-Stage 6 unless there are specific claims or defects to resolve, or externally set performance targets. Indeed, it would seem that few clients ever assess or analyse how well their building performs for them or benchmark it against the objectives they had for it at the outset. Stage 7 addresses this disconnection.

Stage 7 is also when the long-term cost and function of a building is assessed, which in turn affects its viability in terms of whether:

- It is still suitable for the stakeholders.

- It is sustainable.

- It offers value in operation.

Such assessment critically informs work on Stage 0 Strategic definition, whether used to inform a new project or to assess the ongoing viability and purpose of an existing building. It is when critical questions are asked, such as:

- Can or should the building be modified?

- Can or should it be refurbished?

- Can or should it be repurposed?

- Is it time to demolish?

The stage provides robust real-world evidence, allowing clients and project teams to make better-informed decisions.

Because it is running during the entire life of a building, Stage 7 is the longest stage. Over such a period, much can be learned; this should be recorded as asset information and also used for Research and Development. It constitutes a review of the building in the form of building performance evaluation (BPE) correlated with an assessment of the impact on user wellbeing and use effectiveness. For example, it could reveal that a building is very energy efficient yet the users are frequently uncomfortable. It is important to understand both how the building is performing and how well it is supporting the needs and desires of its users and operators.

BPE focusing on internal environmental quality and energy have been undertaken for a number of years. The Building Services Research and Information Association (BSRIA) runs the initiative supporting a specific process called Soft Landings for the design, construction and commissioning, and the initial period of operation, of building-services systems. Stage 7 provides the opportunity to integrate this proven effective process into the wider review, study and analysis of a building in use, which includes all aspects of the building and the uses occurring within it.

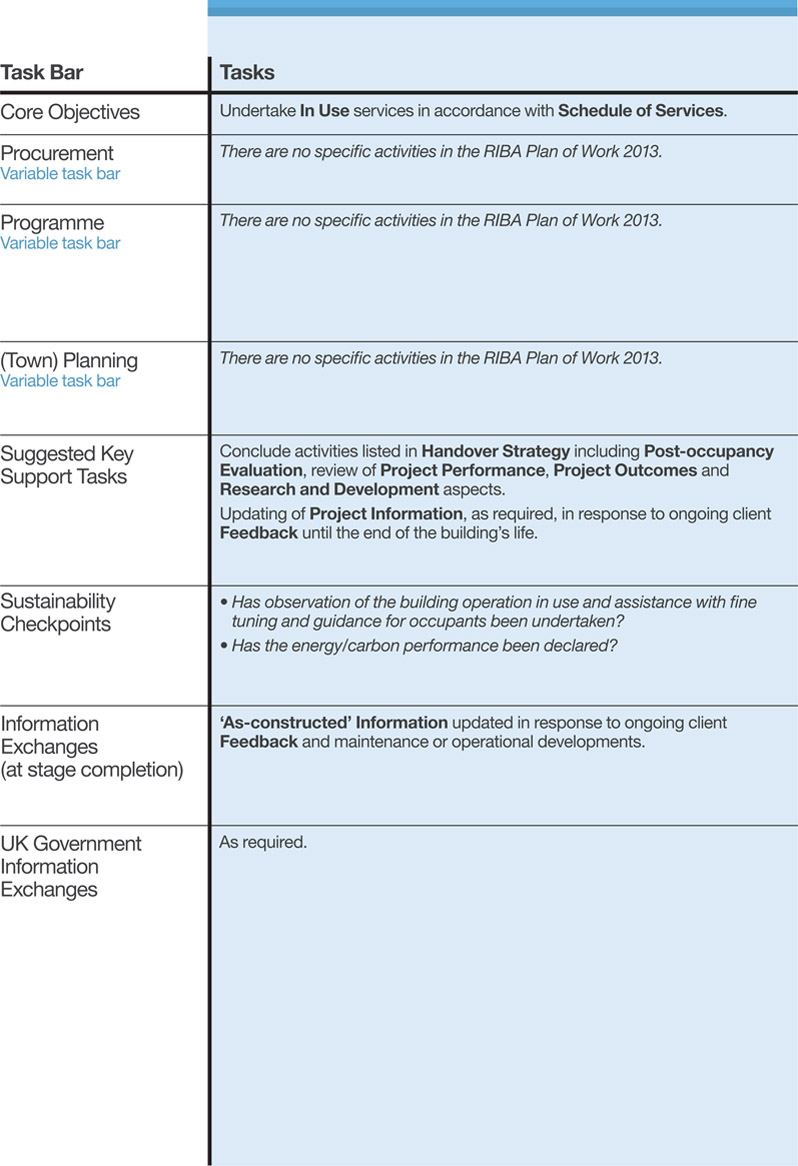

![]() The Circular Plan of Work

The Circular Plan of Work

What is learned at Stage 7 is valuable, both to improve the operation and use of an existing building (feedback, following Stage 6) and to inform a new project (feedforward, informing Stage 0). This is how Stage 7 forms the link in the circular RIBA Plan of Work 2013; it deals both with going forward and reviewing what has gone before.

What Happens at Stage 7?

Although Stage 7 applies to the entire useful life of a building this does not necessarily mean constant activity. Rather, it is likely to comprise targeted interventions at specific intervals, although data on aspects of building performance may well be collected constantly. When undertaking a Stage 7 process, one of the first activities is to develop and agree what such targeted interventions will review, at what frequency, and what data is or could be made available and for what purpose.

For example, on a domestic property this might involve reviewing energy use and comfort levels over changing seasons, whilst in a large, complex building such as a hospital, it would involve assisting and informing the facilities-management team who operate the building for the benefit of medical users and patients alike.

2.1

Feedback and feedforward are rooted in Stage 7 and converge in Stage 0.

The tasks and activities undertaken during Stage 7 are generally the same whether they are performed at the end of a project or to inform the start of a new project, however context for these changes dependent on whether they are performed after Stage 6 or before Stage 0.

Stage 6 into Stage 7

Stage 7 should not be confused with the commissioning and handover implemented in Stage 5 and completed in Stage 6. The Handover Strategy established and implemented in Stage 6 must be concluded and the Project Information completed such that the building can be optimally operated and used. This is the starting point for Stage 7.

Used in this way, the primary purpose of activities in Stage 7 is to provide feedback.

![]() Feedback

Feedback

Feedback occurs when the outputs and outcome of a building project are ‘fed back’ as inputs of a review of cause and effect that forms a circular process. Refining and fine-tuning the operation of a building project can be seen as feedback into itself: examining why something happened, and what happened as a result.

![]() Building Performance Evaluation

Building Performance Evaluation

Building Performance Evaluation (BPE) is a form of Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE) which can be used at any point in a building’s life to assess energy performance, occupant comfort and make comparisons with design targets (source: BSRIA).

Stage 7 into Stage 0

Stage 7 can also be used to provide information and evidence for Stage 0 Strategic Definition and Stage 1 Preparation and Brief. This may relate to a client’s own building or operations, or to those of others.

In this use, the primary purpose is to feed forward into new projects.

This is informed by the review and analysis of a similar operation, activity or building, and is likely to include a review of:

- The procurement strategy for the design team and the contractor.

- Construction methods.

- Capital costs versus operational cost.

- How it is performing, or has performed, in use:

- ~ Efficiency.

- ~ Functionality.

- ~ Environmental performance.

- Levels of user satisfaction.

- Maintainability.

- Durability of materials and engineering systems.

In this context, Stage 7 data is collated and analysed for use in Stage 0.

Feedforward

![]()

Feedforward is a method of briefing that illustrates or indicates a desired future outcome. Feedforward provides information and data about what a project could do correctly in the future, based on review of previous or immediate experience, either in contrast to what one has been done in the past or to repeat or improve upon. The feedforward method of briefing is informed by feedback, thereby understanding why something happened and what actually happened. It may be decided to plan for repeating that outcome, or to develop a plan for what needs to happen to provide a different outcome.

What do we Mean by a ‘Building in Use’?

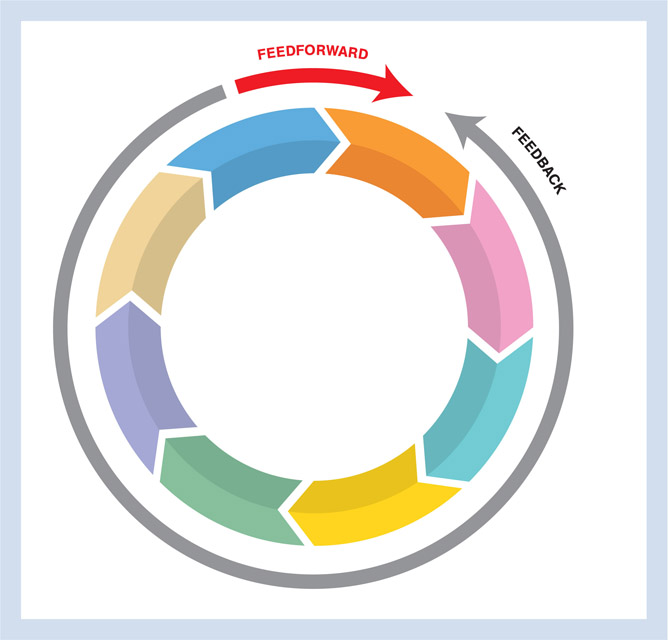

Initiatives such as Soft Landings and CarbonBuzz (both explained later in this chapter) highlight issues of the performance gap between building-systems targets and the actual energy consumed. Stage 7 takes an even wider view of the issue, and looks at all aspects of a building’s performance and its users, taking a whole-system approach. A building in use can be understood and described as a ‘complex adaptive system’.

2.2

A patient-centric hospital viewed as a complex adaptive system showing the factors influencing its performance.

Complex Adaptive Systems

![]()

Complex adaptive systems are defined as ‘complex macroscopic collections’ of relatively ‘similar and partially connected micro-structures’, such as similar rooms or spaces in a building. In the case of a building in use at a macro scale, this comprises the architecture, the building services and the occupants who use and operate it. Such a system is complex because these combined elements form an ever-changing network of interactions; the relationships between each are not simple aggregations of the individual, static entities; rarely can one aspect of a building system be considered without appropriate consideration of all others. People in buildings are adaptive in the way that individual and collective behaviour changes and reorganises itself in relation to how the building influences what they do and how they interact with it.

For example, many domestic environments are controlled with simple thermostats and heating systems turned on and off by a timer clock. Such simple systems have no direct connection with external environmental conditions or variations in occupancy and user behaviours. A colder than expected morning could mean that occupants wake to a cold house, so they adjust the thermostat. During the day, temperatures return to seasonal norms but the thermostat is not adjusted back, and the following morning the home is too hot. Thermostats are not designed to be used as a switch, yet frequently they are used as such. Such reactive actions can all too easily trigger a chain of unintended consequences, impacting users’ comfort, wellbeing and the real and perceived effectiveness of a building.

At the time of writing, we are entering the era of the Internet-of-Things, Sensors, Big Data and Machine Learning. The ways in which people interact with buildings is changing fast, both at the scale of ‘smart buildings’ and ‘smart cities’. These technologies enhance insight and understanding of how buildings work ‘in use’, making analysis and responsiveness easier, and improving insight into actual human behaviour through both quantitative and qualitative data. As these technologies become ever more pervasive, so will the insight available from data and the potential impact of Stage 7, from its application to a family home through to the most complex of buildings.

![]() Definitions

Definitions

Internet-of-Things (IoT) is the interconnection of digital devices within the existing internet infrastructure. Typically, IoT is expected to offer advanced connectivity of devices, systems and services that goes beyond machine-to-machine (M2M) communications. In a building, this would, for example, mean that every aspect of a Building Management System (BMS) would also be linked with the business systems used by the occupant company. In a domestic environment, it could mean ‘smart’ thermostats, which learn occupants’ behaviours and preferences, that are connected to weather forecasts and live, external environment conditions.

Sensors will detect many factors of a building system in use, offering bi-directional information triggering automatic system adjustment and reaction in real-time or even proactively. Sensors in this context would be integral to an IoT environment.

Big Data is an all-encompassing term for any collection of large data sets that were once difficult to process. Recent advances in computing power allow such data to be processed – and at super-efficient speeds. Such data is characterised by being:

- Large to enormous in volume.

- Typically very varied in nature.

- Often available at a near real-time velocity.

Big Data is already being used to better understand and predict traffic and pedestrian flows, to inform retail, enhance web browsing, to better manage and predict emergency rescue situations and even to predict aspects of human behaviour. There is no reason that similar solutions should not soon emerge for the better management and operation of buildings.

Machine Learning is a scientific discipline exploring the construction and study of algorithms that can ‘learn’ from data. Such algorithms operate by building a model based on inputs and using that to make predictions or decisions, rather than following only explicitly programmed instructions. In the example of the smart thermostat, this means that requesting a higher or lower temperature will not directly control a heating system. Rather, it will inform the home system of the occupants’ desire to be warmer and then make an intervention based on all available Big Data from Sensors connected in a system of IoT – in turn, learning the occupants’ preferences and providing more consistent and optimal levels of comfort.

The Performance Gap: Why Don’t Buildings: perform in use as indicated in the brief?

The performance gap is when a building’s performance is not that predicted during design. This can manifest itself in a variety of ways, but some of the most obvious include unexpectedly high utility costs and fluctuating, uncomfortable internal environments. Some matters will have become evident and been resolved during stage 6, but others may not show up until later and can persist for much of the life of a building. Performance gaps that relate to specific Project Outcomes not being optimally met may negatively impact on productivity in an office building, learning in a school or wellbeing in a home. Such gaps will almost always only become apparent over time, or indeed may not be apparent until specific studies or a review are undertaken.

During Stages 0 and 1, a building users’ needs are established. During Stages 2 or 3, when the project team develop design solutions to meet these needs, a cause of subsequent performance gap can manifest itself from decisions made without reference in-use data. Problems may appear later, in Stages 4 and 5. Value engineering by contractors or subcontractors can have a major effect on system efficiency and ease of use. What appears to be a saving on capital expenditure can (and, all too often, does) result in a building that may have been cheaper to construct but is significantly more costly to run and/or negatively impacts on the users and erodes the value of the Project Outcome that caused it to be built in the first place.

Stage 7 addresses this gap through feedback review that reveals the cause of performance gaps in buildings in use. It can address problems in an existing building – or, as feedforward, inform future projects.

Therefore, to mitigate performance gaps Stage 0 and 1 should always be informed by Stage 7 evidence. Then all subsequent decisions during design and construction should be made with this knowledge and insight. Doing so will firstly avoid repeating known performance-gap-inducing decisions and, as the Stage 7 knowledge base grows, result in better-performing buildings that are Project Outcome focused.

Stage 7: The Value for Clients

Stage 7 provides value for clients because it helps them understand how their asset is working for its intended purpose, through insight and knowledge of how well their building works and how best to operate and use it. A continual, regular review process can greatly assist a client in understanding the effectiveness and appropriateness of a building to support their and the building users’ needs and wants. It assists better-informed decisions, whether a client is considering a new project or looking to ensure optimal Project Outcomes from an existing building.

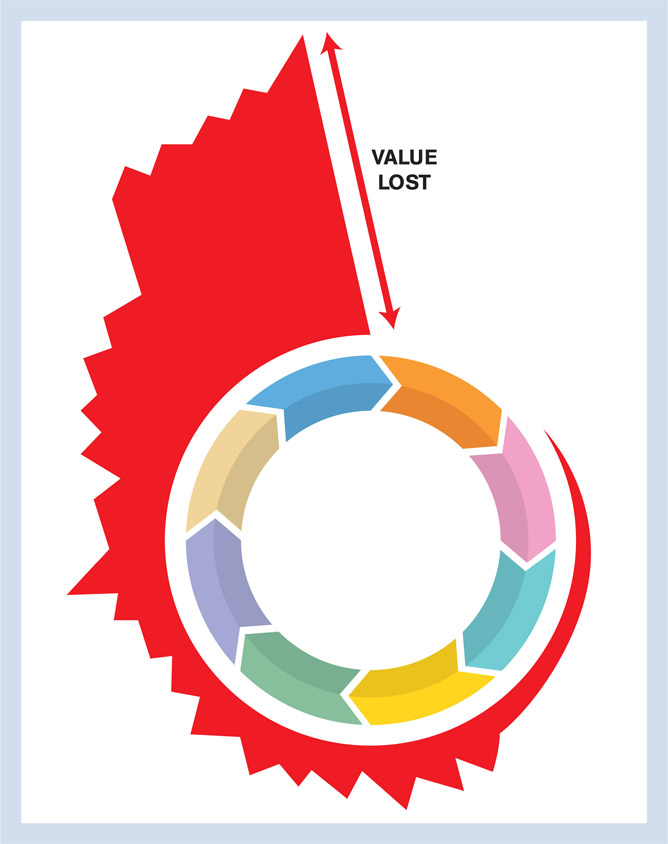

2.3

If Stages 0 and 1 are done poorly or inadequately, resultant costs are likely to rise and be unpredictable – with a resultant loss in value.

Deciding to start a new project and to progress beyond Stage 0 is a big step that involves considerable financial commitment, and the expenditure of time and resources. Good Stage 7 information provides the evidence to support sound decisions and helps ensure the decision is made and the information informing those decisions is comprehensive and robust. The best decisions are made with the best information.

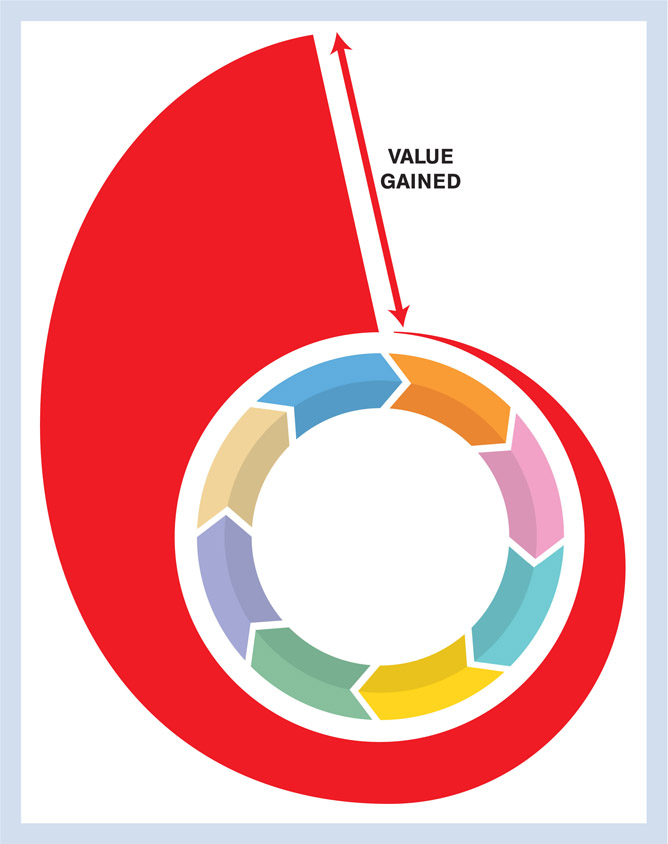

2.4

If Stages 0 and 1 are done robustly, resultant costs are appropriate and as planned – with a resultant net gain in value.

![]() System Control Interfaces

System Control Interfaces

Regardless of the scale or complexity of a building and the associated building-services systems, it need not be complicated to operate. A frequent problem, especially in buildings with complex environmental requirements, is that systems-control interfaces are too complex for the operatives involved, and as a result do not get used to full efficiency. Stage 7 can be instrumental in identifying this, developing retrospective interventions as appropriate and, most significantly, avoiding the issue arising again in subsequent projects.

During a building’s lifetime, the Stage 7 value lies in optimising and refining its operation to best suit the client’s Project Outcomes and their ongoing and potentially evolving requirements.

Such knowledge should be captured in the evolving asset information (based on the previous Project Information), which over time will become ever more valuable to building owners, operators and users alike. Asset information can greatly assist with ongoing maintenance, repairs or substantiating warranty issues in addition to scheduled routine cleaning, maintenance and replacement regimes. It is conceivable that, just like a second-hand car that has been maintained and serviced regularly retains more value than one that has not, the same will be the case for a building.

Hence, Stage 7 also is the correct and logical point of reference for financial decisions about the relationship between capital and operational expenditure, and for assessing the true value of a building.

![]() The Value of Stage 7 to One-Off Clients

The Value of Stage 7 to One-Off Clients

Many building projects are the first (and often only) project a client will undertake. In such cases, the value of Stage 7 lies in bringing knowledge and information from related projects, either through specific study, from the designers’ own database or from the ever-growing sources of data available both in written form and online, such as CarbonBuzz.

Stage 7 is not an Entirely New Stage

Prior to the Plan of Work 2013 this post-project work stage existed as Stage L ‘Post Practical Completion’. This consisted of:

- L1 - Administration of the building contract after Practical Completion and the carrying out of final inspections.

- L2 - Assisting the building user during the initial occupation period.

- L3 - Review of project performance in use.

However, in practice the main focus of this stage was contractual, and was undertaken by a contract administrator without the input of designers or other members of the project team who had been involved in the Briefing or design stages of a project. Stages L2 and L3 were, all too often, token gestures – if done at all. Certainly, it was uncommon for output from these stages to inform subsequent projects. Much of the former stage L1 is now within Stage 6. L2 is effectively the transition from Stage 6 into Stage 7, which builds upon and expands the former Stage L3.

Who is Best Placed to Undertake Stage 7?

Stage 7 is client- and end-user-focused, comprising the study, analysis and diagnosis of a building in use. As the awareness and benefit of the value of Stage 7 grows, the diversity of experts involved is likely to expand – along with a growing interest and willingness of Stage 2–6 project teams to proactively engage in Stage 7 activity. Expertise in architecture and building physics is necessary, but those professions with understanding of human behaviour, both physiologically and psychologically, are becoming increasingly relevant. As Big Data becomes more prevalent in buildings, experts in data collection and processing will also be likely members of the project team for Stage 7.

![]() Engaging in Stage 7 Activity

Engaging in Stage 7 Activity

Anyone involved in the design and construction of buildings should, and can, meaningfully engage in Stage 7 activity. What is required is a shift in emphasis from ‘problem solving’ through design and construction to one of the ‘diagnosis’ of cause and effect. The willingness and participation of the building users is critical, but equally important is the necessary shift in industry attitudes to properly learn from previous projects and to embed that learning in subsequent projects.

Although it is typically a client who will instigate and support Stage 7 activities, there is huge opportunity for project teams to offer periodic review of a building that they designed and constructed. Such reviews provide valuable material for Research and Development, promote ongoing client relationships and may well lead to future project opportunities.

The client and users are therefore at the heart of this stage, and it cannot be undertaken without them. Clients may set the agenda for Stage 7, but in many cases they will need support and advice to get the best from this stage and to understand the tools and methods most appropriate to their circumstances and needs. Services provided by a project team or specific advisors should be provided in accordance with the Schedule of Services, agreed as early as possible in the project.

There are many different types of client, and an even greater diversity of building types and users. Who or what a client is – an individual or an organisation – and the end users that their building accommodates will determine the services appropriate at Stage 7. Sometimes this work is carried out in-house within the client organisation, at other times it will need other project team members. It is vital to have a clear understanding of some of the challenges and activities that building owners and operators face.

For instance, the client at Stage 7 might be:

- The end user of the building or project (eg a householder or a business).

- An individual or an organisation wishing to develop a building for the use of others (a developer).

- The owner of a site wanting to find a viable and deliverable use for it (a landowner).

On a domestic project, the owner-occupier will undertake the vast majority of Stage 7 tasks personally – but may require, and will certainly value, support and advice from their project team. There is an ever-growing availability of IoT devices, such as smart thermostats, that allow households to better operate and control their environments to suit their needs. Energy suppliers are also providing such technologies as an incentive to existing and new clients.

![]() Smart IoT Devices

Smart IoT Devices

Smart IoT devices were a nascent market only a few years ago, but today are experiencing exponential growth. Such devices are very likely to have a huge long-term impact on building users’ understanding and expectations of the environments they live and work in. Design Team Members would be well advised to familiarise themselves with these devices and technologies; advising on and understanding ‘smart buildings’, and especially ‘smart homes’, is both a real opportunity and likely near-future everyday expectation.

As the task of operating and maintaining a larger building has become more complex and time consuming the discipline known as facilities management (FM) has evolved. By definition, FM is the practice of coordinating a physical workplace with the people and work of an organisation. It integrates the principles of business administration, architecture and the behavioural and engineering sciences. The opportunity offered by Stage 7 here lies in linking the skill and knowledge of those who operate and manage a building with those who design and construct it.

What are the Core Objectives of Stage 7?

The core objectives of this stage are to undertake comprehensive building-performance evaluation (BPE) combined with Post-Occupancy Evaluation (POE). Both are tried and tested process methodologies that are instrumental in undertaking Stage 7.

BPE typically focuses on the performance of the whole building understood through a study and review of its constituent systems, with an emphasis on building physics. Conversely, POE focuses more on building operators and users and their perception of building operation, and how well it supports their needs and aspirations. Both of these methodologies have individual merit run separately; however, the greatest possible value from Stage 7 is achieved through their combined use. For instance, a BPE might be commenced during Stage 6, with the findings then used to inform a POE run later in Stage 7. Equally, in feedforward scenarios both are valid methodologies for collecting and analysing information to use at Stage 0 Strategic definition and Stage 1 Preparation and Brief.

The specific in-use services that will be defined in the Schedule of Services will depend on the scale of project and building, and also on whether the form of procurement or contract includes for in-use status. Such services will also be aligned with operator and user experience, ranging from simple homeowner to FM team in the case of a complex building with many diverse users, such as a large office, university or hospital.

![]() Post Occupancy Evaluation

Post Occupancy Evaluation

Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) is the process of obtaining feedback on a building’s performance in use. POE is valuable in all construction sectors, especially where poor building performance will impact on running costs, occupant well-being and business efficiency. (source: BRE)

Procurement Issues, the Project Team, Contracts

Rather than (merely) commission the design and construction of a building or simply renting a building based on floor-area rate or location, certain clients and end users are seeking procurement of assured Project Outcomes. Although still a nascent market, procurement is changing to support this process, leading to more performance-related clauses in building contracts, a preference for payment structures based on demonstrable performance, and a greater emphasis on ongoing FM contracts.

This could lead to the emergence of more forms of design-build-fi nance operate (DBFO) contracts. It is also possible that, in the near future, the built-environment ‘market’ will shift towards procurement of service or Project Outcome in preference to commissioning the design and construction of a building – or that, when procuring a building, the emphasis will be on the value derived during Stage 7 In Use.

![]() Service-Based Procurement

Service-Based Procurement

Is where a client is buying specified outcomes rather than specified products. For example future healthcare could see a shift toward procurement of assured healthcare outcomes rather than a specific building typology. An example of a new market where this is evident is Google being the third largest manufacturer of servers, yet they sell none. An example of an evolved market being Rolls Royce who continue to manufacture jet engines but sell ‘thrust’ rather than the engines themselves.

In Design and Build Financial Operative (DBFO) projects and similar schemes, much of the building management and operation is not the direct responsibility of the user. A main contractor, as part of a special purpose vehicle (SPV), takes on the management for many years after completing the design and construction. This means that all the decisions about what the client expects and needs from a well-managed building will have to have been set down and planned in Stages 0 and 1. Doing so should enable clients to make an informed choice of SPV to carry out all aspects of the project, and if done robustly and comprehensively for an SPV to clearly understand the client’s expectations during resultant Stage 7. Therefore for this form of procurement, the circular relationship of Stage 7 into Stage 0 and 1 is particularly valuable. Indeed, in such procurement methods Stage 7 becomes a contractual obligation.

The operation of all but the smallest buildings and individual domestic properties will require some degree of facilities management for day-today operation, and ongoing repair and maintenance. It is not the purpose of this book to provide guidance on building operation or FM. However, an awareness of the nature and diversity of tasks and activities that comprise typical FM processes can be useful in understanding the Stage 7 In Use context.

Responsibilities for Building Operation and Facilities Management

![]()

Space management

This is a comprehensive system for centralising and storing real-time information about the building(s) and space to be managed, along with the groups and people that will occupy them.

Strategic (organisational) planning

Strategic planning within an organisation aims to anticipate and accommodate changes in the market, such as global expansions, workforce reductions and/or use of contract workers.

Asset management

This enables the ability to track multiple classes of assets – office equipment, furniture, laboratory apparatus, or corporate artwork. Assets can be linked to BIM databases, with location, ownership and access to product information. The system can be integrated with other systems, barcodes or enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems.

Real-estate portfolio management

Relevant to portfolio-holding clients, this is a way to view properties, floor areas and other building information within an organisation, giving management the tools and resources to make decisions and reduce costs.

Lease administration

This centralises all lease information for both owned and leased properties, enabling lease data to be shared within an organisation.

Move management

This process can manage the move of one or more employees within an organisation as well as co-locating a cross-functional group or reorganising an entire location, while delivering better customer benefits through a reduction of move costs and improved service.

Project management

FM or other building maintenance teams use project management methodologies in order to operate on time and budget with facilities projects. Key concepts and deliverables within this form of project management (as distinct from, but with clear similarities with the project management required in Stages 2–6).

Preventive maintenance

Preventive maintenance, scheduling and work orders enable staff and organisations to extend the life of equipment by keeping an inventory and detailed history of the building equipment – both HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) and MEP (mechanical, electrical and plumbing) – and the associated maintenance requirements. Project and Asset Information forms the basis for maintaining an inventory of building equipment with maintenance and cost history.

The Programme Drivers for Stage 7

2.5

A truer representation of the stages’ correlation to actual time.

It is unrealistic to consider that a Project Programme would span the entire useful life of a building, as typically this will be decades in duration. However, it is entirely appropriate that the transition from Stage 6 into 7 establishes the basis for a Stage 7 regime of review and Feedback at planned key intervals – for example, one year into stage 7 and again five years later. Equally, a Stage 7 review could be instigated because of a desired change of use or change in a user’s requirements. Therefore, a Stage 7 programme will often evolve and develop during the life of a building in response to the needs of the owners, operators or users. The exceptions are PFI and DBFO contracts, which will necessarily have specified contractual Project Outcomes for Stage 7 over defined timescales as discussed earlier in the context of the DBFO.

![]() Feedback Sessions

Feedback Sessions

Feedback sessions involving the project team are becoming more established, and are proving very valuable to many organisations – client, design and construction alike. They may take the form of regular or one-off workshops. These seek to identify the best aspects of the Project Outcome, in both process and product, and to identify things that did not work well – not in order to apportion blame, but to correct mistakes where possible and to avoid repeating them in future projects

When Stage 7 is being used to inform Stage 0 for a new project, information might be obtained from a building with a review and Feedback regime in place or a regime might be implemented in a building to assess its viability or performance. Such a study could be done over as little as a period of weeks, but could easily be over months or even years. Stage 7 data can also be sourced from online resources such as CarbonBuzz.

![]() Carbonbuzz

Carbonbuzz

A free, online platform for comparing the design and operational energy performance of a variety of building types, jointly developed by RIBA and CIBSE (the Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers).

As Stage 7 links the circular process of the Plan of Work, it can be either the start of a Project Programme or the conclusion of one – or, indeed, both.

Are Planning Issues Relevant at Stage 7?

Most planning issues will be resolved long before a building is in use, but, increasingly, projects are required to demonstrate that they have achieved the performance standards that were required by the planning approval process.

These requirements will often be set out in planning conditions or in Section 106 legal agreements related to planning approval. In order to fulfil these requirements, data and performance information will need to be collected and presented in an appropriate form.

Common areas in which performance may need to be monitored for planning purposes include:

- Energy performance – demonstrating in use that the building is achieving the standards that it set out to, and that were agreed.

- Travel plans – checking that agreements that encourage sustainable modes of transport are in place.

- Phased projects – where the outcomes of one phase affect what needs to be delivered in subsequent phases, or where standards or planning policy may have changed; for example, on housing projects this may include unit numbers, mix or tenure.

It also worth ensuring that all planning conditions have been discharged and that legal obligations are, and continue to be, complied with. Some of these will require action well after the building or project has been handed over and is in use.

The Key Support Tasks at Stage 7

Post-Occupancy Evaluation

Following user occupation, it is important to check whether the Project Outcomes, as established in Stages 0 and 1, have actually been met. Measuring and evaluating against the Strategic, Initial Project and Final Project Briefs is an important part of checking that the Business Case has been met, and it may well be a condition of funding or planning. Such measurements should not be restricted to purely building-specific systems such as meter readings but, critically, should also include the activities of the building users and their wellbeing.

Examples of POE questions for different building types include:

- Is the school achieving the intended educational and behavioural outcomes?

- Is the new sports facility helping to meet sport-development goals as planned?

- Is the new headquarters office allowing the company to expand and develop as necessary?

- Have the low-energy-use targets been attained in operation, so that the display energy certificate (DEC) information can be verified?

These questions cannot be fully answered in the first few weeks of a project, or by looking at operations on a superficial level. They can only be addressed by implementing an effective Stage 7 process that is related to the specific Project Outcomes and Project Performance.

Studies could require a building to go through a full year of seasons or to have completed specific series of activities, such as a school term or academic year or production or processing of the product of an organisation. A house designed to accommodate the needs of a growing household will potentially take years to demonstrate and realise its full potential.

On simpler projects, such as a single family home, POE can be carried out using basic, informal questionnaires. On larger and more complex schemes, a range of specific, focused and structured tools such as Building Use Studies (BUS) methodology or the Construction Industry Council’s (CIC’s) Design Quality Indicators (DQI) are best deployed. Questions about user satisfaction, energy efficiency, space efficiency and whether the procurement process gave value for money all need to be measured differently, with specific tools and techniques. Knowing which to use and how is becoming a specialist area of expertise, with a growing number of consultants developing and offering specific BPE and POE services.

Definition

![]()

Building Use Studies Methodology (BUS)

A standardised approach to BUS aims to provide feedback on how well a building and its systems are performing from the users’ perspective. The analysis of surveyed information is benchmarked against other buildings that have also carried out BUS, therefore allowing for useful comparisons of different performance metrics. The BUS methodology can be a valuable tool for discovering and understanding comfort problems within buildings.

Design Quality Indicators (DQI)

These can be applied to any project, and are very useful at Stage 7. Whether or not it was used earlier in the project to define design objectives, it can be used now to assess how well the building is performing under each of the categories.

Project Performance

Project Performance is, in essence, a measure and assessment of both how well the building is working in use and how effective the processes of developing that building through Stages 0 to 6 were in achieving that outcome. How this Project Performance is shaped and presented will depend on who is using it and at what stage – from a project team reviewing their performance to a client assessing the viability of a building, to a client and project team jointly gathering evidence to inform Stage 0 for a new project.

Project Outcomes

Project Outcomes are, in essence, what you get once the building is complete and in use. At Stage 0, the desired Project Outcomes are established; at Stage 1, this is translated into a brief that drives and informs Stages 2 through to 6. It is at Stage 7 that you learn how well this was done, and what could be learned to ensure that subsequent projects are as good or better.

Research and Development

Stage 7 provides a rich source of information, data and insight for the Research and Development of better building systems, designs and technologies. Through accessing existing Stage 7 information or specifically seeking new Stage 7 information, much can be learned about how buildings actually operate in use, allowing Research and Development of new and improved methods of procurement, design, construction and operation. In both healthcare, education and the workplace, studies have been carried out exploring the impact and effectiveness of these environments in-use. Where this becomes most valuable is when it is applied to subsequent project in Stage 0, 1 and onwards.

Asset information

At Stage 7, Project Information becomes asset information, and should be continually updated throughout a building’s life. This will inform future changes and interventions, and allow for refinement and fine-tuning of operation. Updating the information can be an ad hoc or structured process, to suit the needs and requirements of the client or users. As Sensors and Big Data become ever more pervasive, information (data) will be collected constantly, with algorithm-driven machine learning updating asset information dynamically. Clients will benefit from maintaining and regularly updating asset information in order to better understand their buildings and to inform future building projects; project teams will benefit from enhanced design and construction knowledge; and building operators from better insight into repair, maintenance and operation strategies that are evidence based.

Tools and Tasks that Support BPE and POE

For BPE and POE activities, there is an ever-growing number of methodologies, processes and tools. Some of the more established and common include:

- Focus groups, exploring the specific experience of user groups or activities.

- Monitoring of organisational activities (how well is the organisation able to perform its business in the building?).

- Observation of use patterns, including use of sensors for detecting patterns of use.

- Tracking the project’s successes and failures, using methods including social media.

- Matching areas used for different activities to those planned at Stage 1.

There are several established tools and methodologies, including;

- BSRIA Soft Landings.

- BUS (Building Use Studies) Methodology (ARUP).

- Specific BPE energy tools;

- ~ TM22 Energy Assessment and Reporting Methodology (CIBSE).

- ~ TM31 Building Log Book Toolkit (CIBSE).

- ~ TM39 Building Energy Metering (CIBSE).

- ~ Model Commissioning Plan (BSRIA).

- Design Quality Indicators (CIC).

- Key performance indicators – KPIs.

- CarbonBuzz (RIBA and CIBSE).

- BRE Environmental Assessment Method – BREEAM (Building Research Establishment).

- Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design – LEED (US Green Building Council).

As with Stage 7 itself, BPE and POE constitute an evolving and growing area of interest and specialism; they will continue to improve, and new tools and approaches will emerge.

![]() Definitions

Definitions

Model commissioning plan

A guide to developing a comprehensive commissioning plan that aims to ensure that relevant commissioning takes place and is recorded correctly.

Key performance indicators (KPIs)

KPIs are simple numeric metrics of energy usage or observed building characteristics that can be associated with better or worse performance. Much like KPIs in other business organisations, these are intended to yield the best information for the least cost and analysis time. This process helps to keep energy usage as low as possible by providing specific KPI feedback to those who influence energy usage. Ideally, KPIs allow:

- Designers to better understand the impact of their design choices as distinct from operator or occupant choices.

- Designers and owners to have a simple framework to reference when defining requirements for energy-monitoring equipment and analysis for their new or existing building project.

- Building operators or building auditors to have standard KPIs to assist.

- Tenants or owner-occupants to compare their energy use against other, similar spaces in order to determine their impact on the overall building energy use.

LEED

LEED is a set of rating systems for the design, construction, operation and maintenance of ‘green’ buildings, homes and neighbourhoods.

BSRIA Soft Landings

Soft landings merits specific reference; it was developed, by BSRIA, primarily for the design, specification, commissioning and operation of building-engineering systems, such as heating, cooling and lighting. BSRIA runs the Soft Landings initiative, developing and publishing the official guidance and arranging training. The Soft Landings process mapped to the Plan of Work starts in Stage 1 and continues into Stage 7 but is commonly known in Plan of Work terminology as the Handover Strategy. The process enables design engineers and constructors to improve the operational performance of buildings and provide valuable feedback to project teams. Soft Landings also requires designers and constructors to remain involved with buildings beyond Stage 6, to assist the client during the first months of operation and beyond, to help fine-tune and debug the systems, and to ensure that the occupiers understand how to control and best use their buildings.

In essence, Soft Landings involves:

- Achieving greater clarity at the inception and briefing stages about client needs and required outcomes.

- Placing greater emphasis on building readiness, by designer and constructor having greater involvement during the pre-handover and commissioning stages.

- A resident Soft Landings team located on site during the users’ initial settling-in period.

- Remaining involved after occupation, during and beyond the defects liability period to resolve outstanding issues.

Soft Landings requires designers and constructors to spend more time on constructive dialogue with the client, and in setting expectations and performance targets on energy and end-user satisfaction.

During Stage 7, Soft Landings typically envisages continued involvement by the client, design and building team over a three-year aftercare period. This can greatly assist the operators to get the best out of a building; it also is an ideal framework from which to establish a whole-building-life regime of review and Feedback from users and operators alike.

The Soft Landings process allows everybody involved to benefit from the lessons learned from occupant-satisfaction surveys and energy monitoring. The worksteps in Soft Landings enable operators and users to spend more time on understanding interfaces and systems before they occupy the building. The designers and key contractors are tuned to understand and support the end users in the critical, early period of occupation.

Adopting the Soft Landings approach is an excellent basis for longer-term Stage 7 activities.

The Benefits of Research and Development

Stage 7 is the ideal time for project teams to learn how well their projects have worked. Through research on a building in use and analysis of Project Performance, very valuable Feedback can be acquired. Such activities are not only hugely valuable in understanding what worked well and what could be improved on a subsequent project, but also present one of the best ways for more junior and less experienced members of any project team to understand the impact and effect of their actions during Stages 2 to 6. The process can also have a very real and positive benefit in fostering ongoing client relationships. Any client who sees that their project team has a continuing interest and commitment to the building that they designed and constructed is very likely to consider that team favourably for any subsequent projects.

Project teams can also learn much about their own performance, how well they communicated and responded to the needs of each member of the team and, most especially, to the client. Such research could lead to the development of new and preferred working methods that the team and clients can benefit from on subsequent projects.

Equally, by providing information to internet portal sites such as CarbonBuzz, the whole industry has an opportunity to research and develop better methods and solutions through the study and analysis of buildings in use.

Sustainability Checkpoints: at Stage 7

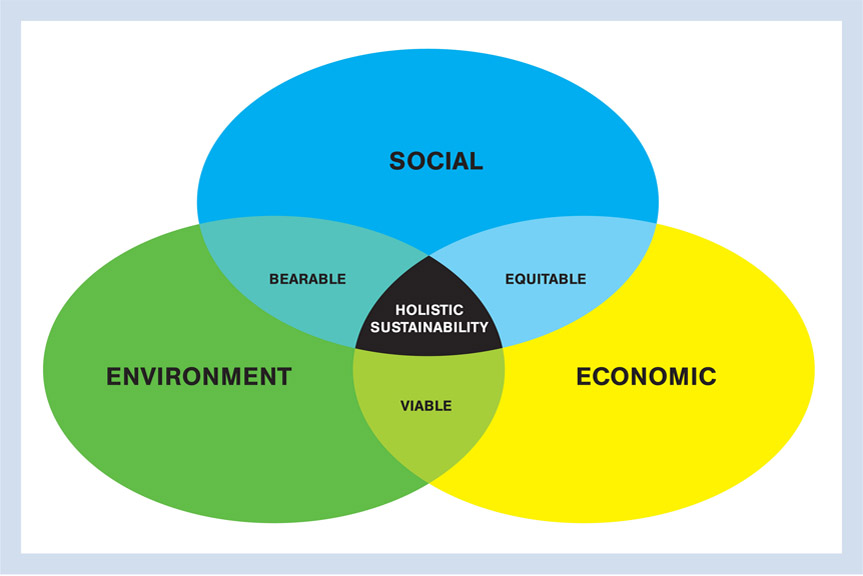

Stage 7 is when you find out and understand just how sustainable a project actually is. At this time the impact of holistic sustainability – which includes social, economic and environmental factors – can be fully assessed. When setting the sustainability aspirations of a building during Stage 1, much can be learned from Stage 7 information from previous projects.

2.6

Holistic sustainability unifies factors of society, economics and environment.

Stage 7 is where the effectiveness of all the previous stages is fully understood. The building is in use, and its performance, effectiveness, value and overall ability to support the project outcomes defined at Stages 0, 1 and 2 can be confirmed, measured and assessed, providing the fullest indicator of whether or not it is sustainable. This Stage 7 information is also a vital source of data for subsequent Stage 0 activities on new projects or opportunities. This could be through specific study of existing buildings, from a client’s property database, from a project team’s individual or collective knowledge base, from professional-institute databases or from open public sources such as CarbonBuzz and BREEAM.

Sustainability measurement during Stage 7 assists clients in bringing environmental performance and financial impact into balance – on, for example, managing critical information; energy performance; water usage; or energy-specific retrofits.

Sustainability measurements could include:

- Analysis of building environmental impacts (energy, water, greenhouse-gas emissions, recycling, waste and others).

- Integration with the display energy certificate (DEC), to calculate carbon footprint and energy-use costs.

- Forecasting the project’s financial impacts (net present value, internal rate of return, return on investment, payback period) and environmental impacts.

- Structured building assessments and certifications using rating systems like those offered by LEED or BREEAM.

- The participation of both occupants and management in the understanding of and access to sustainability information.

Information Exchanges: Who needs to know about the outcome of Stage 7?

Information Exchange at Stage 7 for a specific building will occur between client, operator and end users, the project team responsible for both the design and construction and any ongoing Stage 7 services. Through portals such as CarbonBuzz, exchanges are occurring within the construction industry at large, and ultimately with the whole of society. It is not overstating the case to say that Stage 7 is the most important stage in the Plan of Work 2013 because of its ability to influence and shape the evidence used to operate existing buildings, and also to shape the Briefing of new ones. It is both the start and end of the process of delivering the most holistically effective built environment possible.

During Stage 7, the ‘As-constructed’ Information will, in all likelihood, be updated and refined to suit the needs of in-use building operation, becoming, in the process, asset information. This is the case whether we are talking about 2D CAD drawings or a more comprehensive Building Information Modelling (BIM) database.

In the same way that BIM is impacting on Stages 2 through 5, information technologies systems are relevant to Stage 7 in the form of computer-aided facilities management (CAFM). CAFM systems can provide much information and data for Stage 7.

![]() Computer-Aided Facilities Management (CAFM)

Computer-Aided Facilities Management (CAFM)

CAFM systems assist organisations with meeting their compliance obligations through ensuring that assets are inspected, tested and certified in accordance with statutory and corporate regulations, rules and best practice, and that corrective actions are taken to correct any faults. Records are maintained, and can be readily located and made available for inspection. Typically, they track and maintain the following core facilities items:

- Strategic organisational planning – real estate, business operations, headcount requirements and forecasting future space.

- Space planning and management – allocations, inventory and classifications.

- People management – occupants, vendors and staff.

- Maintenance management – demand and scheduled (preventive maintenance).

- Emergency management – disaster planning and recovery, safety information.

- Capital project management – construction/renovation and move management.

- Lease management – property financial data.

- Asset management – depreciation, equipment, furniture, telecommunications and cabling.

- Building Information Modelling integration – interaction with other programs.

- Sustainability – energy performance, building certifications and sustainable projects.

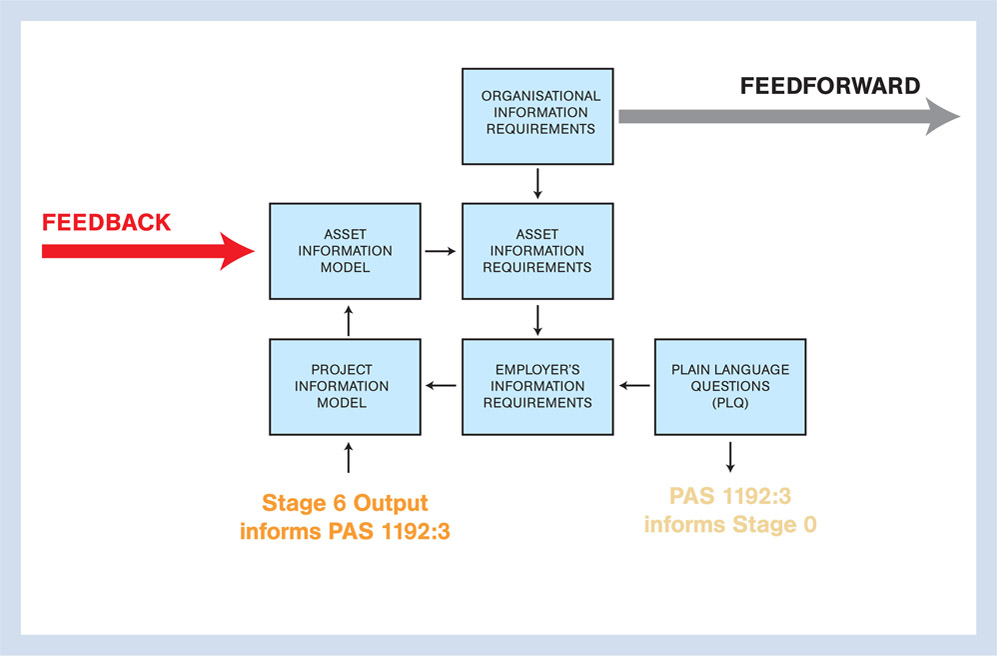

UK Government Information Exchanges

The UK Government (UKG) has a strategic objective to achieve Level 2 Building Information Modelling (BIM) on all public-sector asset procurement, with equal applicability to private-sector building, infrastructure, refurbishment and new-build projects. Publicly Available Specification (PAS) 1192:2 specifies an information-management process to support BIM Level 2 in the capital/delivery phase of projects, setting out a framework for collaborative working on BIM-enabled projects that relates to Plan of Work Stages 2–5. Particularly relevant to Stage 7 is PAS 1192:3 – Specification for information management for the operational phase of assets using building information modelling.

PAS 1192:3

![]()

PAS (Publicly Available Specification) 1192:3 is a partner to PAS 1192:2 Level 2 BIM that sets out a framework for Project Information management for the whole life cycle of asset management. PAS 1192:3 addresses the operational phase of assets irrespective of whether these were commissioned through major works, acquired through transfer of ownership or already existed in an asset portfolio. The framework includes the creation of an asset information model in order to manage Information Exchanges to and from a Project Information model created in accordance with PAS 1192:2; external asset information models, such as CAFM systems; direct supplier inputs, such as digital surveys; or other enterprise information systems, such as financial and portfolio reporting. PAS 1192:3 applies to all UKG-constructed assets, and is therefore key to Stage 7 on such projects.

PAS 1192:3 provides an approach to support the objectives of asset management through the use of asset information.

The requirements within PAS 1192:3 build upon the existing code of practice for governance defined within BS1192:2007 and the content of BS ISO 55000 series and PAS 55.

2.7 Stages 6, 7 and 0 in relation to PAS 1192:3.

Chapter 02

Summary

Stage 7 In Use is about developing a clear and evidenced understanding of how a building works in use, for the purposes of:

- Refining and improving the building’s effectiveness and performance.

- Establishing how well the outcomes established in Stage 0 were met as assessed through in-use study and analysis.

- Post-Occupancy Evaluation and building performance evaluation.

- Assessing, through Project Performance, how effective Stages 1–6 were.

- Capturing that learning to apply, for positive benefit, to subsequent projects through Research and Development.

Stage 7 is not a design stage – it is about information, analysis and learning, in order to enable understanding of the impact of design decisions made earlier in the project. It is often a client-led process and may include specialist advisors or key members of a project team, and be undertaken in accordance with a Schedule of Services. Specific tasks and activities of Stage 7 are often relatively short processes conducted over a day or week, but ideally these are revisited and redone in a Stage 7 which runs through a building’s entire useful life. It is the correct mechanism by which decisions to refurbish, renovate, repurpose or decommission and demolish a building should be made.

Stage 7 is about being clear what the client has achieved and how well the building in use provides an environment that supports their reason for needing the project in the first place.

Stage 7 logically follows Stage 6. Activities commenced and first done during Stage 6 are likely to be revisited at regular planned intervals during a whole Stage 7 period, which is very likely to last many years. This, in turn, informs subsequent Stage 0 activity on new projects, completing the circular nature of the Plan of Work 2013.

Scenario Summaries

WHAT HAS HAPPENED TO OUR PROJECTS BY THE END OF THIS STAGE?

A Small residential extension for a growing family

A year after the family took full occupation, their energy supplier offered them a complimentary smart thermostat in return for changing their tariff. Interested in the smart thermostat but not wanting the energy firm’s input, they contacted their architect to discuss what was available on the market. Although aware of the growing availability of various smart home devices, it was not an area of particular expertise for the architect; however, they had worked previously with an engineer who had specialised in such things. The engineer was introduced to the family, and what started as an initial interest grew into a full domestic BPE and the implementation of an array of sensors and control devices that allowed the family to take charge of the control of their environment and use of energy. The project was so successful that the family have recommended both the engineer and architect to friends of theirs. Both are now engaged on Stage 0 activity for a purpose-built smart home, using the knowledge from this project and others gained through research.

B Development of five new homes for a small residential developer

Two years after the handover of keys from the developer, three owners remain and two new ones have arrived. The buildings are starting to show some signs of wear and tear, especially in the two in new ownership as maintenance was not done by the original owners (they were bought as buy-to-let properties). One of the new owners is particularly keen on reducing energy use in their property. Eager to learn how other owners were using their homes, this owner encouraged the other homeowners to participate in a collective BPE study. Wanting to learn more about how their homes were constructed, the owners discover that the construction firm no longer exists but they do locate the architect. They are now working, with the advice of the architect, to improve heating and control systems and are using their collective buying power to full effect. Involved in the project some years after their commission had ended, the architect realises the value of working with buildings in use, and, as a result, develops a new business model of revisiting all previous projects at two-, fi ve- and ten-yearly intervals.

C Refurbishment of a teaching and support building for a university

Whilst negotiating the retainer, the practice took on a Part III (professional qualification) student with specific experience in BPE and POE. The design team develop a proposal, incorporating this new knowledge and skill into the Feedback methods that they are familiar with. The university are particularly interested in this more comprehensive offering, have now retained the design team for ongoing BPE studies across all the buildings on the campus and are currently using this information for Stage 0 work on a new centralised, sustainable energy system for the campus. The POE team are working with academics and students to assist in aligning research aspirations with best use of the available spaces.

D New central library for a small unitary authority

The new library is working well, and the community are making great use of the space and availability to access books and other resources. The links between BMS and BIM are proving both clumsy and overly complex for the authority librarians. Funding cuts mean that a dedicated BMS operator is unaffordable. However, a local firm specialising in Internet-of-Things solutions offers to roll out a low-cost CAFM system. Integrating the BIM data, connecting to the sensors and controls of the BMS in combination with the book-lending (barcoded) system now means that the building BMS is ‘learning’ about the patterns of occupation, self-adjusting and modifying to provide optimal comfort. The library staff are able to focus on the task of supporting the community and managing the library assets as an integral part of the whole building system. The library soon becomes one of the most effective and efficient assets that the unitary authority own.

E New headquarters office for high-tech internet-based company

Rebalancing of the BMS occurred after the required three-month period stipulated at the end of Stage 6. Since then, the company has developed online tools linking the building’s BMS to an outsourced CAFM facility, which, in turn, they have linked to their own enterprise workflow systems. This has facilitated a building environment that is aware of the activities and location of every single person working for the firm. This has brought massive benefits in terms of whole-life holistic sustainability, as energy used (environmental), overhead cost per employee (economic) and quality of the workplace flexibility and effectiveness (social) all have added value benefit. The building is now adjusted to suit and accommodate the dynamic working practices of the company. Interested in a Research and Development project to explore just how far this could be taken, the company have re-engaged the original project team and brought in Internet-of-Things expertise combined with hydrogen energy experts. They are currently exploring how surplus heat can be harvested as hydrogen, and be provided to employees to power hydrogen vehicles and to heat schools in their immediate neighbourhood.