Chapter 1 I Know I Can Finish Most of This (If I Stay Late)

I Know I Can Finish Most of This (If I Stay Late)

In This Chapter

- Designing a campaign to win back your time

- Making subtle changes that you can stick to

- Feeling good about leaving work on time

- Establishing a plan—and following it

For the heck of it, let’s begin this book at the beginning. One of the most insidious time traps you can possibly fall into is believing that by working a little longer (or taking work home on the weekend) you can finally “catch up.” This is a fallacy that will keep you perpetually chasing the clock for at least the rest of your career—and maybe the rest of your life.

Hey, I sympathize with you if you’ve found yourself staying at the office later, or toting a bulging briefcase home with you. At face value, these maneuvers probably seem to be the logical response to the pressures you face. For too many people, however, they are also a trap.

Staying Longer Ain’t the Answer

If you find yourself perpetually taking work home or working a little longer at the office, putting in overtime becomes the norm. Soon you’re taking another 30 i(40 pages of reading material home at night as if this habit were simply the way it is.

Chronos Says Now and then it makes sense to take work home from the office. All career achievers do. During specific campaigns (such as the launch of a new business, product, or service), when you change jobs, or when you’re approaching a significant event, it makes sense to bone up and spend a few extra hours at work. But this should be the exception, not the rule.

When you consistently work longer hours or take work home from the office, you begin to forget what it’s like to have a free weeknight—and eventually a free weekend. I’ve observed the working styles of some of the most successful people in Eastern and Western society: multimillionaires, best-selling authors, high-powered corporate executives, association leaders, top-level government officials, educators, people from all walks of life. The most successful people in any endeavor maintain a healthy balance between their work and non-work lives.

Americans are working longer hours, but not everybody puts in marathon work days. The typical German worker, by comparison, works 320–400 fewer hours per year than his American counterpart. A journalist for U.S. News and World Report observed that Europeans are shocked to discover that most Americans get only two weeks of annual vacation time. The norm in Germany (as well as France and Great Britain) is five weeks off annually. American entrepreneurs, as a whole, work the longest: an average of 54 hours a week, if you believe they’re reporting their true work time (they probably work many more hours than they reported).

Americans, in general, also are sleeping less (the subject of Chapter 8, “To Sleep, Perchance to Not Wake Up Exhausted”), which significantly affects work performance. In fact, all aspects of life are becoming more complex. As a result, you may be enjoying your life a bit less these days (Chapter 3, “With Decades to Go, You Can’t Keep Playing Beat the Clock,” discusses five mega-realities that may tell you why).

Time Out! U. S. Department of Labor statistics reveal that in the past quarter century, the amount of time Americans have spent at their jobs has risen steadily.

People aren’t just working more and scurrying more because they feel like it: Our society as a whole has become more competitive and demanding. Employers require more. Kids seem to have to be part of more activities. There are kabillions of entertainment options. So we work more hours, try to keep up, quietly go nuts, and consider it normal.

Part-timers, Students, and Homemakers Are Not Exempt

Doesn’t anybody get a break in this world? Nearly all the time-pressure problems that plague the denizens of the full-time working world will visit you as well. While you may have extra moments to yourself here and there, everyone who holds any position of responsibility today—and those responsibilities include studying, managing a home, caring for others, and nearly any other pursuit you can think of— faces pressures unknown to previous generations (as you’ll learn in Chapter 3).

A Stitch in Time Your quest becomes accomplishing that which you seek to accomplish within the eight or nine hours you call the workday.

Your key to reducing the time pressure you feel is not to stay longer at work. Indeed, to reclaim your day you cannot stay longer. This will become clear shortly.

The Workday Does End, Just Like Careers and Lives

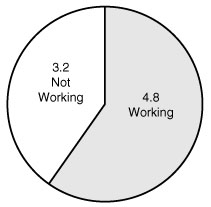

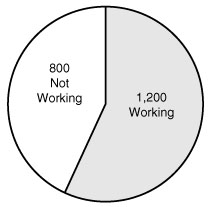

Suppose your workday is 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with an hour for lunch, yielding a total working time of eight hours. Studies show that most people are working only about 60 percent of those eight hours for which they were hired. Even in downsizing times, most people work a daily average of only four hours and 48 minutes on the tasks, assignments, and activities for which they were hired. Notable exceptions include the self-employed and the fanatically driven. When everyone around you is fanatically driven, whoa boy, that can seem normal!

Per 8-hour work day.

Per 2,000-hour work year.

Many people don’t work a full eight hours a day, even though they spend eight hours on the job, as these charts illustrate.

Excuse me! So maybe you’re not among those who dawdle—and you certainly don’t goof off for 40 percent of your day. Still, it’s unlikely that you’re working the full eight hours. Among the many factors that inhibit your inclination to work a solid eight hours every day are these:

- Too many domestic tasks. See Chapter 7, “Money Comes and Goes—Time Just Goes,” to learn how easy it is to get stuck thinking that if you spend a few minutes here and a few minutes there taking care of domestic tasks yourself, you can 1) stay on top of it all, 2) save a little money, and 3) cruise into work in high gear.

- Not getting enough sleep. Zzzz. See Chapter 8, “To Sleep, Perchance to Not Wake Up Exhausted,” which discusses why you’re probably not getting enough sleep, and how this leads to lack of efficiency and effectiveness.

- Overcommitting. See Chapter 9, “Volunteering a Little Less—and Liking It,” about how widely available technology gives managers and businesses the opportunity to get more done—and also to expect more from their employees. Much more.

- Not being sufficiently organized. See Chapter 10, “Making Your Office Work for You,” which explains that a desk is not a filing cabinet, and that window sills and the corners of your room are not permanent storage locations. You can rule an empire from a desk if you know how to do it correctly.

- Lacking effective tools. See Chapter 12, “Neat and Uncomplicated Tools to Manage Your Time,” on how you can put new technology to work for you—and how to avoid being overwhelmed by what you acquire.

Beyond these factors, over-socializing is the norm in many offices. Some professionals develop elaborate rituals, such as sharpening three pencils, refilling the coffee cup, making a personal call, or waiting until the clock on the wall is at the top of the hour before they get down to work. (I know, that’s not something you would ever do, but some people do this.)

2,000 Hours to Make a Difference

Eight-hour workdays, of which you have about 250 a year, yield a work year of 2,000 hours. Can you get done in 2,000 hours that which you want to do (or for which you were hired)? Yes—2,000 hours, 200 hours, eight hours, even one hour, can be a great deal of time if you have the mindset, the quiet environment, and the tools you need to be productive.

Leaving and Feeling Good About it Takes Discipline ( . . .at First)

To sustain the habit of leaving work on time, start with a small step. For example, decide that on every Tuesday you will stop working on time and take no extra work home with you. After freeing up Tuesdays for an entire month, perhaps add Thursdays. In another month, add Mondays; in the fourth month, add Wednesdays. I’m assuming there’s no way you work late on Friday! (Or do you? If you do, then start with Fridays!)

Time Out! If you deplete yourself of crucial elements to high productivity by coming to work feeling exhausted or mentally unprepared—or if you keep getting interrupted—one hour, eight hours, 200 hours, 2,000 hours, or more won’t be sufficient for you to do your work. (See Chapter 18 for a simple system to minimize interruptions.)

What transpires in the first month when you’ve decided that each Tuesday will be a normal eight- or nine-hour workday and nothing more? Automatically you begin to be more focused about what you want to get done on Tuesdays. Almost imperceptibly, you begin to parcel out your time during the day more judiciously.

By midday, stop and assess what you’ve done and what else you’d like to get done. Near the end of the day, assess what more you can (realistically) get done and what’s best to leave for tomorrow.

You begin to set a natural, internal alignment in motion. (Sounds exciting, doesn’t it?) Your internal cylinders fire in harmony to give you a vibrant, productive workday on Tuesday so you can leave on time.

Chronos Says For some reason that only the gods of Mount Olympus can explain, once you’ve solidly made the decision to leave on time on Tuesdays, every cell in your body works in unison to help you accomplish your goal.

Preparing for the Unforeseen: Marking Out Boundaries

Okay, so you’re thinking that these resolutions look good on paper, but what about when the boss comes in and hands you a 4-inch stack of reports at 3:45 in the afternoon? Or what about when you get a fax, an e-mail message, or a memo that upsets the applecart? These things do happen—and not just to you!

Take a real-world approach to your time, your life, and what you’re likely to face during the typical workday. Consider how to approach the predictable impediments to leaving on time on Tuesday.

Rather than treat an unexpected project that gets dumped in your lap late in the day as an intrusion, stretch a tad to view it as something else. You got the project because you were trusted, accomplished, or, in some cases, simply there.

Many government workers have no trouble establishing their time boundaries at work. They leave on time because that’s what their government policy manual says, right there in clause 92-513-ak7-1, subclause 8-PD 601-00 07, paragraph 6.12, line 8—no overtime, pal. If you’re in the private sector, however, you may not have such regulations on your side. (See Chapter 9 for some options you do have.)

Overworked, Underproductive

If you’re concerned that staying late and putting in ridiculous hours is de rigueur in your organizational culture, you need data and special strategies. First the data! Professor Carey Cooper, an American at Manchester University in England, is one of Europe’s foremost stress specialists. He has found that performance declines by 25 percent after a 60-hour workweek. He also calculated that the annual cost of stress-related illnesses attributed to overwork topped $80 billion in the United States—more than $1,600 a year for every other worker in America. Other studies show that work output is growing faster in Germany than in the United States—even though (as you’ve seen) Germans work fewer hours than Americans.

Stated bluntly, excess work hours put in by already overtaxed employees are of negative value to an organization when viewed in the context of overall work performance, direct health-care costs, and productivity lost to absenteeism and general lethargy on the job.

Strategies for Survival

Now that you know the downside of overwork, it’s time to learn the strategies for avoiding it:

- Let it be known that you maintain a home office where you devote countless hours to the organization after 5:00 each evening. Then take most evenings off.

- Invite bosses and coworkers to your home for some other reason, and conveniently give them a tour of your command-center-away-from-the-office.

- When you discuss your work, focus on your results (as opposed to the hours you log after 5:00). It is exceedingly difficult for anyone to argue with results.

- Find role-models—outstanding achievers within your organization who leave at (close to) normal closing time at least a few nights a week—and drop hints about those role-models’ working styles in conversation with others in your organization.

- Acquire whatever high-tech tools (see Chapter 12) you can find that will help you be more productive. If your organization won’t foot the bill, do it yourself. Often your long-term output and advancement will more than offset the upfront cost.

- On those evenings you do work late at the office, be conspicuous. Make the rounds; let yourself be seen. After all, if you’ve got to stay late, at least make sure it’s noticed.

- On those evenings when you take work home, use oversized containers or boxes to transport your projects. You may even choose to bring boxes back and forth to the office even when you have no intention of doing any work at home (this makes you look productive).

- If zipping out at 5:00 carries a particular stigma in your office, leave earlier. Huh? Yes, schedule an appointment across town for 3:30 p.m. and when it’s completed, don’t head back to the office. This is a tried-and-true strategy for laggards, but it can work as well for highly productive types like you. If you feel guilty, work for the last 30 or 45 minutes at home.

Watch Words A dynamic bargain is an agreement you make with yourself to assess what you’ve accomplished (and what more you want to accomplish) from time to time throughout the day, adjusting to new conditions as they emerge.

For now I’m only discussing ending work at a sane hour one night a week. If this represents too much of a leap for you, either stop reading this book and continue suffering the way you have been, or change jobs and try to find a more enlightened employer. Otherwise begin to plot your strategy now: It’s your job and it’s your life.

Bring on Da Crunch Time

On the way to developing Microsoft Windows 98 and getting it out the darn door on time, the elite Seattle nerd corps found themselves working progressively longer hours each day. For some, it became unbearable. Some went into a robot phase (you know, work, work, work, work. . . ). Some quit. Some will be added to the ranks of the millionaires. All got the opportunity to chill out afterward. Yes, there are exceedingly tough campaigns, but they are always of finite duration.

Crunch times come and go, and they’re often unavoidable. Still, you don’t want to get into the bind of treating the typical workday like crunch time. When you do, you start to do foolish things—like throwing more and more of your time at challenges instead of devising less time-consuming ways to handle them—and that means not leaving work on time tonight, tomorrow, or any other night in the foreseeable future.

Make a Great Bargain with Yourself

A master stroke for winning back your time at any point in your day—Tuesdays or any other day—is to continually strike a dynamic bargain with yourself. It’s a self-reinforcing tool for achieving a desired outcome that you’ve identified within a certain time frame, as in the end of the day! Suppose it’s 2:15 and you’d like to accomplish three more items before the day is over. Here’s the magic phrase I want you to begin using:

“What would it take for me to feel good about ending work on time today?”

This is what I mean when I talk about a dynamic bargain. I have this powerful question as a poster on my wall in my office. It can give you the freedom to feel good about leaving the office on time because, when you answer it each morning, you’re making that bargain with yourself—you’re stating exactly what you’ll need to accomplish to feel good about leaving on time that day.

Suppose that today your answer to the question is to finish three particular items on your desk, after which you can feel good about leaving on time. Now suppose that the boss drops a bomb on your desk late in the day. You automatically get to strike a new dynamic bargain with yourself, given the prevailing circumstances. Your new bargain may include simply making sufficient headway on the project that’s been dropped in your lap, or accomplishing two of your previous three tasks and x percent of this new project.

Thank God It’s Friday, and I Feel Good About What I’ve Done!

The same principle holds true for leaving the office on Friday: feeling good about what you accomplished during the work week. Here is the question to ask yourself (usually sometime around midday on Friday, but even as early as Thursday):

“By the end of work on Friday, what do I want to have accomplished so I can feel good about the weekend?”

By employing such questions and striking these dynamic bargains with yourself, you get to avoid what too many professionals in society still confront: leaving, on most workdays, not feeling good about what they’ve accomplished, not having a sense of completion, and bringing work home. If you’re like most of these people, you want to be more productive. You want to get raises and promotions, but you don’t want to have a lousy life in the process!

A Stitch In Time Regardless of projects, e-mail, faxes, phone calls, or other intrusions into your perfect world, continually strike a dynamic bargain with yourself so you get to leave the workplace on time, feeling good about what you accomplished.

Rather than striking dynamic bargains with themselves, most people frequently do the opposite. They’ll have several things they wanted to accomplish that day—and actually manage to accomplish some of them, crossing them off the list. Rather than feel good about their accomplishments and accept the reward of the freedom to leave on time, they add several more items to the list—a great way to guarantee that they’ll still leave their offices feeling beleaguered. Here you have the perfect prescription for leaving the workplace every day not feeling good about what you’ve accomplished: If you always have a lengthy, running list of “stuff” you have to do, you never get a sense of getting things done, and you never get any sense of being in control of your time.

A Self-Reinforcing Process

When you’ve made the conscious decision to leave on time on Tuesday and strike the dynamic bargain with yourself, almost magically the small stuff drops off your list of things to do. You focus on bigger, more crucial tasks or responsibilities. On the first Tuesday—and certainly by the second or third—you begin to benefit from a system of self-reinforcement, whereby the rewards you enjoy (such as leaving the office on time and actually having an evening free of work-related thoughts) are so enticing that you structure your workday so as to achieve your rewards.

Watch Words A system of self-reinforcement is a series of rewards you enjoy as a natural outcome of particular behaviors.

Eventually, when you add Thursdays, then Mondays, then Wednesdays to the roster of days that you leave work on time, you begin to reclaim your entire work week. A marvelous cycle is initiated. You actually

- leave the workplace with more zest.

- have more energy to pursue your non-work life.

- sleep better.

- arrive at work more rested.

- are more productive on the job.

And as you increase the probability of leaving another workday on time, you perpetuate the cycle and its benefits.

Choosing to Leave on Time at Will

How do you get this ball rolling? Declare that the following Tuesday will be an eight-or nine-hour workday and nothing more. You leave on time that day feeling good about what you’ve completed. That’s it—no grandiose plan, no long-term commitment, no radical change, and ’nary any anxiety.

If you’re having trouble giving yourself permission for this one-day, no-overtime treat, recall how long you’ve been in your profession, and remember that you’re in your present position for a lengthy run. On no particular day and at no particular hour are you truly rooted to your desk. After all, you’re a professional. You’ve gotten the job done before; you’ll get it done now as well. Feel free to trust your own judgment about when it’s okay for you to go home.

Now it may be that on a given day when you’ve decided you’re going to leave on time, something happens to upset your workload so that you have more to do than you can get done that day (and when won’t that happen?). The temptation will be to stay late and deal with the new task. Resist it! Instead, map out exactly what you’re going to begin on the next morning to handle this addition to your workload. Preparing a plan for tomorrow will reduce any anxiety or guilt you feel about leaving on time today. Ultimately, you’ll have little anxiety or guilt. After all, you have a right to a personal life, don’t you?

Let everyone in your office know that you’re leaving at five, or whatever closing time is for you. Announce to people, “I’ve got to be outta here at five today,” or whatever it takes. People tend to support another’s goal when that goal has been announced. Some people may resent you for leaving on time; fortunately, most will not. You have to decide whether to let the resentful attitudes of a few control your actions.

If you must have a list of “steps,” here’s what you can do on that first Tuesday, or any other day, to leave on time when you choose to:

- Announce to everyone that you have a personal commitment at 5:30 that evening. If you have a child, you could say your child is in need of your assistance.

- Mark on your calendar that you’ll be leaving at five.

- Get a good night’s rest the night before, so you’ll feel up for the effort of fulfilling your dynamic bargain with yourself.

![[image]](http://imgdetail.ebookreading.net/detail/detail3/9781101198735/9781101198735__the-complete-idiots__9781101198735__Images__extra_time.jpg) A Stitch in Time

Silently repeat to yourself, “I choose to easily leave at closing time today and feel good about it.” Never mind if at first you think this mantra doesn’t have any power. Do it. You’ll find yourself leaving more often, more easily, and on time.

A Stitch in Time

Silently repeat to yourself, “I choose to easily leave at closing time today and feel good about it.” Never mind if at first you think this mantra doesn’t have any power. Do it. You’ll find yourself leaving more often, more easily, and on time. - Eat a light lunch; it keeps you from being sluggish in the afternoon.

- Strike a dynamic bargain with yourself at the start of the day, in late morning, in early afternoon, and in late afternoon. (Remember, it’s okay to modify the bargain to accommodate a changing situation.)

- Regard any intrusion or upset as merely part of the workday, deal with it as you can, and plan tomorrow’s strategy for coping. Do not let it change your plans about leaving on time today.

- After striking the dynamic bargain with yourself, don’t be tempted to add more items to your list at the last minute.

- Envision how you’ll feel when you leave right at closing time (but there is no reason for you to be staring at the clock for the last 45 minutes).

- If you want support, ask a coworker to walk you out the door at closing time.

Chronos Says This chapter is intentionally simple, if for no other reason than this: The more you have to do and have to remember, the less you’ll do and the less you’ll remember. Your only assignment, boiled down to four words: Leave workontime.

Ensuring that you leave the workplace on time may seem too involved to accomplish. If you engage in only two or three of these steps, however, you’ll still get the reinforcement you need.

The Least You Need to Know

- You deserve to leave on time—atleast occasionally—and to feel good about it.

- Depending on your organization’s culture, you may have to use one or more of the strategies discussed in this chapter to leave on time.

- The changes you need to make have to be easy to follow. If they’re too difficult, they won’t hold. Winning back your time requires only small steps, but a progression of them.

- To leave on time, start with one day per week (such as Tuesday) and strive to leave on time every Tuesday for an entire month.

- You can strike a dynamic bargain with yourself to feel good about what you’ve done, choose what else you want to accomplish, and feel good about leaving.

- As you develop the habit of leaving on time, you develop a positive cycle of high productivity, even while leaving on time more often.