Chapter 3

The Risk Arbitrageur

Nothing is right in all markets at all times.

—John Paulson, May 2011 Midyear Investor Conference

Hedge fund manager John Paulson had traveled from New York to Capitol Hill to address the Committee on Oversight and Government Reform on November 13, 2008. A series of well-executed complex trades at the height of the financial crisis had made Paulson a very rich man at a time when many banks and institutions were on the brink of collapse. Among these was a trade that has been widely hailed as far and away the greatest trade in financial history, one that earned his firm a record $15 billion by the end of 2007. Now Congress wanted to hear what he had to say about the systemic risks that hedge funds posed to financial markets, and to listen to proposals for regulatory and tax reforms.

Paulson was not the only hedge fund manager who had been summoned by the Committee that day, although he was certainly the best performing over the past year. Joining him was fellow subprime winner Phil Falcone, as well as George Soros, the head of Soros Fund Management, Jim Simons of Renaissance Capital, and Ken Griffin of Citadel, all industry legends and billionaires in their own right. Each of these industry titans would have his turn to address the Committee, but right now the floor was Paulson’s. The entire room, indeed, the entire financial world, wanted to hear what this man had to say; his remarks were running live on CNBC, Bloomberg, and, of course, C-SPAN.

“Chairman Waxman,” he began, calm and unruffled, peering through his dark-rimmed glasses at Henry Waxman, the liberal Democratic congressman from California who was presiding over the hearing, “the problem in the U.S. financial system is one of solvency. In general, financial institutions are undercapitalized and have insufficient tangible common equity to support their overlevered and deteriorating balance sheets.” Perfectly silent, the room hung on his every word. “Remarkably, the average tangible common equity to total tangible assets for the 10 largest U.S. banks is only 3.4 percent, or 30 percent leverage. The solution to solve the problem is to strengthen their balance sheets by raising equity both privately and publicly.”

Addressing Congress was an uneasy moment for Paulson. He didn’t like being called onto the carpet, so to speak, to justify his successes. He’d been in the business for over 15 years focusing on event-driven transactions, and the financial crisis of 2008 happened to be the biggest event-driven trade since the Great Depression.

Paulson began his testimony with a synopsis of his background— graduating summa cum laude from New York University (NYU) in 1978, attending Harvard Business School as a Baker Scholar in 1980, and working as a managing director of mergers and acquisitions at Bear Stearns. He opened his hedge fund in 1994, and by 2008, it was the fourth-largest such fund in the world. He then explained how it happened that his firm managed to pull off a $15 billion trade. He explained that, in 2005, he and his team had become concerned about weak credit underwriting standards and excessive leverage among financial institutions believing that credit was fundamentally mispriced. “To protect our investors against the risk in the financial markets, we purchased protection through credit default swaps on debt securities we thought would decline in value due to weak credit underwriting. As credit spreads widened and the value of these securities fell, we realized substantial gains for our investors.”

Paulson explained this as if it were just that simple. The funny thing is, to Paulson, it was that simple.

He concluded his testimony with some recommendations for steps the government could take to relieve the credit crisis. The top idea, one that he had just offered in a Wall Street Journal op-ed article, was for the U.S. government to “purchase senior preferred stock in selected financial institutions, which provides for maximum taxpayer protection.” Following his op-ed, the Troubled Asset Recovery Program (TARP) was reoriented to focus on the purchase of preferred stock. When John Paulson speaks, people listen.

The Making of a Risk Arbitrageur

Sitting with John Paulson on an April afternoon, it is easy to see why people—friends and investors alike—have always flocked to him. He is a financial genius, of course, but socially savvy as well. People feel safe around him and trust him.

On the fiftieth floor of 1251 Avenue of the Americas, we talk easily over Diet Cokes in a long conference room with plush cream carpeting overlooking the midtown skyline, skyscrapers surrounding us. Paulson looks right at home. An avid runner, the 55-year-old is fit and slightly tanned.

“Let me tell you a little about what I think I do. I think what I am is a risk arbitrageur,” he tells me. From a small beginning as a $2 million fund with just one analyst and a receptionist in 1994, the Paulson & Co. portfolio has risen to a gargantuan $38.1 billion as of June 2011 with 51 investment professionals. It is the fourth-largest hedge fund in the world, according to a recent ranking by hedge fund trade publication AR Magazine. The portfolio is divided across the $6.5 billion Paulson Merger Funds, the $9.7 billion Credit Opportunities, the $3.0 billion Recovery funds, and the $1.1 billion Gold funds, and the $17.9 billion Advantage funds.

Paulson & Co. specializes in three types of event arbitrage: mergers, bankruptcies, and any type of corporate restructuring, spin-off, or recap litigation that affects the value of a security.

In merger arbitrage, a major focus of the firm’s proprietary research is to anticipate which deals may receive another bid, and then to weight the portfolio toward those specific deals. The goal of the Paulson funds, like any fund, is to produce above average returns with less volatility and low correlation to the broader equity markets. Their correlation with the S&P 500 since 1994 has been 0.07 percent.

But finding arbitrage opportunities is not where the science kicks in. In fact, Paulson says he often learns about big mergers and bankruptcy filings on the front page of the Wall Street Journal just like everyone else. What gives his team an edge over the competition, he believes, is having the skills and special expertise to evaluate both the potential return and the various risks of a potential deal. “It’s very easy to compute what the returns are from a spread,” he says, “but what’s not easy to compute is what the risks of the deal breaking apart are. There’s financing risk. There’s legal risk. There’s regulatory risk, amongst others.”

Other corporate events are also in the news, but Paulson looks beyond the face value of these events to find the bigger impact. As an example, he points to the Macondo oil spill that devastated the Gulf of Mexico during the summer of 2010. The event depressed the prices of BP, Anadarko Petroleum Corporation, and offshore drilling contractor Transocean. “We established that the decline in the price of these securities exceeded the ultimate liabilities,” he says, “and an arbitrage opportunity exists between where the securities trade today and where we estimate they’ll trade once this liability is settled.” As a result, Paulson purchased shares in Anadarko in late 2010 and early 2011, according to 13-F filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and hedged these positions with short positions in oil exchange-traded funds (ETFs). The short positions should insulate the portfolio from swings in the oil sector or broader stock market isolating the potential return to the settlement of the liability.

Risk arbitrage investing, a specialty of the New York financial community, began in the 1930s with investors buying bankrupt bonds and swapping them into other securities when the company emerged from bankruptcy. The arbitrage spread is the difference in the value of the bonds purchased in bankruptcy and the value of the securities post-reorganization. Because of the complexity, the risks, and the specialized skills needed to invest in this area, the spreads can be wide and the annualized returns high. Over time, risk arbitrage evolved to include other types of corporate restructurings such as mergers, spin-offs, restructurings, and litigation that could affect the value of a security independent of the market.

A risk arbitrageur, Paulson explains, typically gets involved when others want to get out. “Say you get a $50 offer from a company that was trading at $35 and it immediately jumps to $49,” he offers. “Now most investors don’t want to stick around for the last dollar and risk losing $14 if the deal breaks. They made a good profit and want to take the property and go home. On the other hand, the arbitrageur steps in, and for that extra dollar, takes the $14 risk of deal completion. Now a dollar may not sound like a lot. But a dollar over 50 is roughly a two percent return. And let’s say it’s a tender offer and will close in 60 days. That means you can do that deal six times a year so six times two is a 12 percent rate of return. That can be an attractive rate of return for a relatively short-term investment.”

But a 12 percent return isn’t outsized by any means, let alone by hedge fund standards of excess. There are other reasons to invest, namely the fact that risk arbitrage is not correlated with the market. “Let’s use that same example,” he says. “If you bought the stock at $49, and the market fell 10 percent over the next two months—you would still earn that 12 percent annualized return, just as long as the transaction closed. The beauty of arbitrage is you can earn good returns that are noncorrelated with the market. A deal like this could get exciting if another bidder came in and offered $60. That would be a 20 percent bump, or $10. That would boost the return from 12 percent annualized to 120 percent annualized. It doesn’t happen all the time but it happens often enough that we spend a lot of time trying to determine which of the announced deals could get a competitive bid to capture that potential excess return.”

Traditionally, there were three major specialists in risk arbitrage: Goldman Sachs, Bear Stearns, and Gruss Partners. All three of these institutions would end up leaving their mark on Paulson as he climbed the sky-high ladder on Wall Street.

Paulson, in many ways, developed his core risk arbitrage skills well before he landed on the Street. When he was five, his grandfather Arthur bought him a pack of Charms candies during a visit. The next day, he sold the candies to his kindergarten classmates. After they counted the proceeds, Arthur took his grandson to a candy store where the six-year-old bought a pack of Charms for five cents. The difference between the sales proceeds and the cost of the pack was the profit. His grandfather instilled in him an appreciation of math and numbers. It worked. “I liked buying and selling. I would take the profits I made and put them in a piggy bank—that was what I called ‘the bank.’ Eventually, I filled up the bank and that’s what I thought banking was. So at a very young age, I wanted to be a banker.”

A good student, by eighth grade, Paulson was taking high school–level courses in calculus and Shakespeare as part of a program for gifted students. But he also thrived on independence and soon started to dabble in stocks with some money his father had given him when he was about 14. He was instantly hooked and spent time every day poring over the New York Times stock pages. Paulson recalls: “They had the high and low for the year column, so I said, ‘I’ll go find the stocks that are trading at their lows with the widest discrepancy.’ I found that in a stock called LTV.”

At the time, LTV had a high of $66, a low of $3, and was trading at $3. Paulson bought it with the idea that he would buy, trade, and then sell it as soon as the stock went back to $66. It just wasn’t going to be that easy—instead of going up, LTV went bankrupt. So how did it end up yielding some of the largest returns he ever made in a stock? Paulson kept the worthless stock in his portfolio, and when the company emerged from bankruptcy, he received out-of-the-money warrants in LTV Aerospace. LTV Aerospace took off like a rocket ship. While Paulson was at Harvard, the company was bought out and his stock was suddenly worth around $18,000.

Accidentally, he had received his first lesson in bankruptcy investing and warrants through LTV. Paulson says: “It was a portfolio position I barely even knew I had and it couldn’t have been more speculative, but it turned into a high multiple return. Those warrants are tricky little instruments.” He taught himself some very valuable basic lessons early on like how to read stock tables, earnings reports, and account statements; a little bit about bankruptcy reorganization; and, of course, what a warrant was.

When Paulson entered college in 1973 he had no interest in business. With antiwar and civil rights protests front and center, “Nothing in business was fashionable. It was all about counterculture.” As a freshman, he worked on fulfilling his general curriculum requirements with classes in creative writing, philosophy, and film production. But school wasn’t enough to keep him focused; he needed a break.

When his father, Alfred, bought him a plane ticket to South America to help brighten his mood, Paulson readily embarked on what would become an extended journey through Panama and Colombia that finally ended in Ecuador, where he would stay for over two years. Initially, at 18 he took a job with an uncle who developed condominium projects along the coastal city of Salinas. At first, Paulson was enamored with his uncle’s glamorous lifestyle and his responsibilities but realized he couldn’t make much money on a salary; if he wanted to succeed, he would have to venture out on his own. At 19 years old, he started a business manufacturing children’s clothing and made his first big sale to Bloomingdale’s. He liked being successful, being independent, making money, and having employees, and this exposure gave him his first taste of what it would be like to run his own firm. Gradually, however, he realized that if he wanted to succeed in business, he would have to go back and finish college.

He entered NYU. Two years behind his classmates, Paulson felt a certain pressure. This time, though, he was keenly focused on business and pushed himself to excel, getting straight A’s. As a senior, Paulson took a course that changed his life forever. It was called The Distinguished Adjunct Professor Seminar in Investment Banking, a semester-long course that was led by John Whitehead, who, at the time, was chairman of investment banking at Goldman Sachs.

Whitehead brought in other senior partners of Goldman Sachs to the class including Stephen Friedman, the former head of mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and Robert Rubin, the former head of risk arbitrage, which were described as two of the most profitable areas of Goldman Sachs. Rubin had a reputation as the smartest guy at the firm, and Paulson learned that his department hired only the best and the brightest. He had heard the risk arbitrage department produced the most profitable partners, and Paulson remembers, “That’s when I got very intrigued with both M&A and risk arbitrage.”

But like all good things in life, it just wasn’t that easy. The executives advised the students that if they wanted to work in risk arbitrage, they’d have to first prove themselves in mergers and acquisitions. But they wouldn’t get a job in M&A without an MBA. So Paulson made a decision. He says, “I decided I’d go to Harvard, get my MBA, and then work in M&A and then risk arbitrage. That was my strategy.”

He tactfully executed just that. When the dean of NYU suggested he apply to Harvard Business School, Paulson leapt at the opportunity, and John Whitehead, who was a member of the Harvard Board of Trustees, offered to write his recommendation. After gaining admission, he received the prestigious Sidney J. Weinberg/Goldman Sachs scholarship, an endowment started in 1950 for exceptional students. He was elated.

It was at Harvard that Paulson really hit his stride. After graduating summa cum laude from NYU business school as valedictorian of his class, he felt that he had really earned his spot with the rest of the world’s brightest business-minded students. He joined the investment club and even wrote a guide to investment banking. As a part of the finance club, he sent out surveys to all the major banks asking them specific questions about the firm’s culture and specialties. To his surprise, he got enough responses back to publish the guide. A copy still sits in his office.

Paulson thrived on being challenged in the classroom and felt excited about his future for the first time in a long time. The case study approach made attending class fun for him, and the lively, interactive environment it created appealed to the young student. But it wasn’t until years later that Paulson realized the case study method had instilled in him a better approach to testing potential investments. “When I look back on the experience, it taught me how to analyze situations quickly and how to articulate myself to other people. It showed me how to try and convince people to my way of seeing things.”

When his firm started to hit its stride in the early 2000s, Paulson drew on some of the skills he’d learned in the nonfinance courses he had taken at Harvard: simple concepts like product/market segmentation. In fact, Paulson credits his marketing knowledge for some of his recent success. He says: “You know, one of the ways we grew was not by coming up with more products but by reformulating the same product.”

Paulson Partners originally started out with a domestic merger arbitrage fund in 1994. “While we were not pioneers in the hedge fund space, we still were early in its evolution. By 1996, we thought it may be the right time to launch an international product.”

It was the same product, just targeted to different investors. Paulson says: “It was the same portfolio; Paulson International just targeted a foreign investor base and added all the bells and whistles to appeal to international clients.” The fund today is about four times the size of the domestic fund.

Then they came up with another idea to further extend their offerings: an enhanced version. “You know, ‘enhanced,’ ‘new,’ and ‘improved,’ the name was right out of consumer product marketing,” he says. “And ‘Paulson Enhanced’ is the same exact portfolio as the merger and international funds, only it’s twice as much leverage. These marketing terms helped me create new products for new markets and differentiate the product without more work.” Today, the Enhanced and International funds combined are 11 times the size of the original Paulson Partners Fund.

Paulson & Co. launched the Advantage fund in 2003 and the Advantage Plus in 2004. These funds added to the merger arbitrage base by including bankruptcy, distressed, and other forms of event investing.

Initially, Paulson & Co. grew slowly, but once it had a five-year track record and proved steady performance, making money in both 2001 and 2002, when many other funds were feeling the strain of the post-9/11 market collapse, it started grabbing investors’ attention. In 2002, Paulson was managing $300 million. By the end of 2006, the firm was up to $6.5 billion, and that was before it made any money on its legendary subprime trade. That trade hit in 2007 and earned them $15 billion in profits, bringing Paulson & Co. to $28 billion in assets under management by the end of the year.

One day at Harvard Business School in 1979, a classmate told Paulson to skip squash club for a day, telling him: “You got to hear this guy Kohlberg speak. Jerry Kohlberg’s the one making all this money in leveraged buyouts.” Paulson didn’t know who Kohlberg was, but his interest was piqued and he went along, entering a class of only about 15 people, expecting “nothing special.” Kohlberg, founder of legendary private equity firm Kohlberg, Kravis, & Roberts Co. (KKR), meticulously went into the details of how a leveraged buyout worked, complete with an impressive example of how the firm made a $17 million profit on a $500,000 investment purchasing a company for $34 million. They financed the acquisition with $20 million in bank debt, $14 million in subdebt, and $500,000 in equity. The bank debt was secured, while the subdebt got 16 percent plus warrants. KKR was able to sell the firm for $51 million two years later, pocketing the $17 million profit.

These numbers seemed staggering to Paulson. As he says: “It was a wild amount of money to be making on an investment at that time.”

It was at that point that Paulson decided against investment banking, choosing instead to focus on leveraged buyouts because, as he says, “The principal firms were smaller but they made a lot more money. And the principals were a lot richer.”

At the time, the firms that were doing well in this area were KKR, Odyssey—the former partnership of Oppenheimer—E. M. Warburg, Pincus & Co., and Allen & Co. “They were very different than the big investment banks like Goldman,” says Paulson. “I think the wealthiest man on Wall Street at the time was Charlie Allen, who ran a small bank and made exceptional returns. Like Charlie Allen, Leon Levy and Jack Nash were far wealthier than the senior partners at the other banks. They were the ones on the Forbes 400 list, not the presidents of the investment banks. Although their corporate finance businesses were tiny and they didn’t have the prestige that the larger banks did, for me, I found these people fascinating. I was more attracted to the principal business than the agency side.”

Envisioning himself among those luminaries on the Forbes 400 list seemed impossible to Paulson, but he at least wanted to work for them. As he says: “I called them the financial entrepreneurs. Those are the people I gravitated to, and I wanted to learn what they were doing.”

Upon graduating from Harvard Business School as a Baker Scholar, Paulson accepted a job at Boston Consulting Group (BCG). It was a tough economic period, and the firm paid a large salary, but Paulson soon realized consulting wasn’t for him. While intellectually interesting, he wouldn’t be making deals like Jerry Kohlberg’s or earn the leveraged buyout–type paydays. Despite that, he valued his first job. Paulson says: “Although it wasn’t ultimately where my heart was, my experience with BCG was very useful to me in terms of understanding business strategy and what makes one business better or more valuable than others.”

When he saw Jerry Kohlberg at a tennis match, Paulson approached him, telling him how much he enjoyed his presentation at Harvard, and asked for help finding a job. While KKR didn’t have any openings at the time, Kohlberg introduced him to Leon Levy of Odyssey Partners. Like Kohlberg, Leon was famous among the cognoscenti for making widely successful deals, including the late 1970s’ $40 million buyout of Big Bear Stores, which produced a $160 million gain on a $500,000 investment. He was equally admired for buying one million shares in the bankrupt Chicago & Milwaukee Railroad for $6 per share and selling it several years later for $160 per share.

After a visit to Leon’s posh apartment on the Upper East Side, Paulson earnestly argued why he should work for the hedge fund titan. Odyssey was expanding and needed hardworking young talent. He got the job. Odyssey was one of the original hedge funds, and working for Leon and Jack Nash in their 10-person office helped Paulson build a solid foundation. In fact, most of what he learned there, Paulson still does at his own firm: risk arbitrage, bankruptcy investment, and corporate restructuring of public companies.

Paulson was drawn to Leon and Jack Nash’s tough character and “get it done” attitudes and felt he had the type of thick skin needed to keep up with them. He didn’t realize, though, how his lack of experience in investment banking would hold him back, and he was the first to acknowledge that he needed to learn the business from an agency perspective.

“When they wanted to do a buyout, it was ‘Okay, call some bankers and arrange the financing.’ But coming from consulting, I didn’t know any bankers. I’d never raised any money and I really wasn’t yet equipped to handle that type of responsibility. I realized I’d skipped a very important stage between school and being a principal; I needed to learn the business from an agency perspective. As much as I wanted to avoid earning my dues, being the bottom associate at an investment bank, I realized that the skills learned during that training was what I was lacking. And there was no way around it. If you wanted to be a principal, you had to learn the investment banking business first.”

Nevertheless, Paulson learned a lot about investing at Odyssey and remained in contact with Leon and Jack. In fact, in the late 1990s, Leon and affiliated foundations became the largest investors in his hedge funds.

Paulson felt fortunate to land a job as an associate at Bear Stearns in 1984 right when M&A was taking off. He says: “I felt very lucky to be there, when Ace Greenberg was at the helm running Bear. They didn’t have a lot of people in M&A but had a lot of business. So I worked very hard and advanced fairly rapidly. Associate vice president, limited partner, then managing director all within the span of four years.”

Bear Stearns was the perfect place for Paulson to grow at his own supercharged pace. They placed no limits on how quickly he could climb the ladder or how long he had to remain at each level. They told him they would promote him as fast as he could handle the next level of activity, and they did. Another reason Paulson was able to accelerate so quickly was that he felt he had to play catch-up. Some of the friends he graduated with were four years ahead of him in pay and position at other banks, while he was back at the bottom.

And after four years of learning the ropes at Bear, Paulson felt prepared to play in the big leagues. “Once I got to the point where I had gained the experience advising in mergers, negotiating merger agreements, underwriting common stock, preferred stock, subordinated debt, and senior debt offerings, and having a Rolodex full of capital providers, I felt then I was ready to move back to the principal side. My experience at Bear gave me the building blocks that I needed to act as principal.”

In the late 1980s, Gruss Partners and Bear Stearns together made a large gain on the sale of Anderson Clayton Company and Paulson became close with Marty Gruss, son of Joseph Gruss, the founder of Gruss Partners and the current senior partner. The firm was founded in 1938 and had built an enviable long-term track record in risk arbitrage. Paulson left Bear Stearns in 1988 to become a general partner at Gruss Partners. At that point, the merger business was slowing as Drexel failed and the economy dropped into a recession. Bankruptcy reorganizations were rising, however, so Paulson focused most of his time at Gruss on distressed and bankruptcy investing. As much as he liked working at Gruss, though, he realized that he ultimately wanted to be in business for himself.

“I’m Sort of an Independent Person”

Paulson wasn’t afraid of the challenge of building his own business. “People kept saying that if you start your own business you’re going to fail,” he says, “but I never thought I would. I thought that in order to do well, all I needed to do was compound at above-average rates of return, and I thought, ‘Why shouldn’t I be able to do better than average?’ That seemed to be the easy challenge. So all you had to do was minimize losses and make more than average. If you could do that, you could be successful. And I already had the skills to do that in risk arbitrage, mergers, and bankruptcies.”

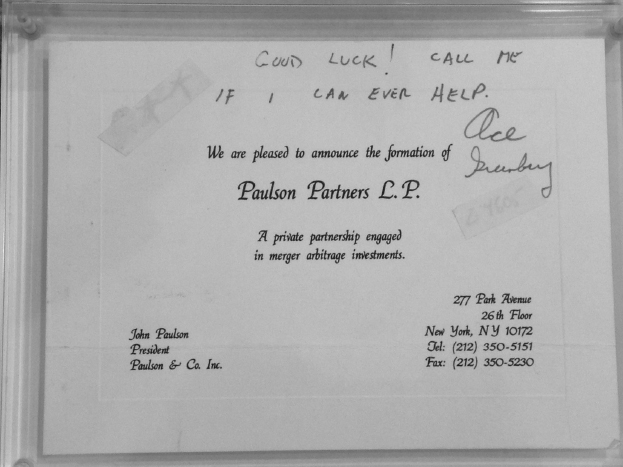

So he launched Paulson Partners in 1994. He started with $2 million of his own money and waited for the phone to ring. He sent out 500 announcement cards to potential investors, saying, “We’re pleased to announce the formation of Paulson Partners,” and told his lawyer he expected “to open” with $100 million.

But raising money was tough. “Although I had a lot of contacts,” he says, “I didn’t have a lot of money. I sent those announcement cards out to everyone I knew, and I thought the phone would ring and everyone would be calling to invest. Well, the phone never rang. I got only one card back from Ace Greenberg offering congratulations.” So Paulson picked up the phone and was met with a mix of indifference, skepticism, and occasional curiosity. “Some did provide a sliver of encouragement and said, ‘John, you know, I like you but you don’t have a track record, so come back when you do.’ ”

Source: Paulson & Co.

Paulson knew he had to build a track record. But this was a daunting task given the small capital he had and it took not a small amount of effort to stay positive. He recalls: “It was so very tough coming to work every day, making calls, having meetings, and then getting rejected. People would avoid my calls or make appointments and then cancel. Some of the junior analysts at Bear when I was there were now partners. I’d call them and they wouldn’t see me—guys that worked for me!”

In an effort to broaden his investor base, Paulson waived the $1 million minimum investable amount, and some encouraging conversations buoyed his hopes. He was disciplined and says: “I started managing the small amount of money I had as professionally as I could. I sent out monthly reports with our performance data to anyone with a vague interest.” After receiving the same letter for 12 months showing very positive results, some of those people who had put Paulson off were now ready to invest.

That arduous process took an entire year before Paulson & Co. finally landed its first investor. Paulson had grandiose expectations that weren’t quite met. “I was like, okay, here comes $10 million! And then it was . . . $500,000,” he said, shrugging.

The allocation came from Howard Gurvitch, a friend and former associate of his at Bear Stearns. Gradually, some other friends began to pile in and Paulson built up his investor base. Then one day he got his first $5 million investor. “This was a very wealthy guy; he had at least $200 million, and he sent me $5 million,” Paulson recalls. “That more than doubled my capital. I was so excited—I was finally at $10 million. He was reading all of these letters and thought that from the way I spoke that I managed more than $100 million. He later told me that if he knew I only managed $5 million, he would never have put in $5 million, since he has a policy against being more than 5 percent of any manager.”

Barely raising enough capital to run his tiny fund took a toll on Paulson. “I had to swallow my pride, buckle down the hatches, and just be patient. I ran the firm professionally in terms of research, portfolio management, monthly reporting and audited results, and doing all the work you needed to do even though the position size was small,” he says. Bear Stearns was a great supporter and lent him office space at 277 Park Avenue on a high floor with nice views, conference facilities, and administrative support. As the fund continued to grow, Paulson gradually started building up a staff, focusing on marketing and administrative personnel.

Eventually, Paulson & Co. started to rack up a good performance record compared to other hedge funds. “We stacked up pretty well, within the top quartile. And being in the top quartile allowed us to steadily raise capital. What distinguished us most was making money in 2001 and 2002 just doing conservative spread deals. We took down our equity exposure and were able to show positive returns when most managers lost money in 2002.”

Although the Paulson Funds only made 5.1 percent in 2001 and 5.4 percent in 2002, it was enough to make Paulson & Co. the top-performing merger manager over that two-year period. Then, in 2003, when the economy picked up, Paulson had returns of 22.7 percent in Partners and International and 45.2 percent in Enhanced.

With a seven- to eight-year track record that proved they could operate well in an up market as well as a down market, Paulson & Co. started getting serious investor attention that brought it to the billion-dollar level. But Paulson & Co. was still a little late to the game. Hedge fund industry growth was slowing, and there were other, well-established managers out there like Farallon, Perry Partners, Angelo Gordon, and Och-Ziff. These firms also had excellent track records, had started earlier, and had a loyal investor base. Paulson wanted to find a way to stand out from the pack. He also knew he could not grow through marketing alone as he could never compete with the extensive global marketing operations that firms like Goldman Sachs or J. P. Morgan had. “I realized that if I wanted to get into the top leagues, it would have to be by performance,” he says. “In 2003, we had our first taste of 40 percent performance, and with very little volatility. That was the magic.”

Once Paulson & Co. got into 2005 and 2006, its assets steadily grew to $4, $5, $6 billion and above but it still wasn’t enough to be considered one of the biggest players in the field. Paulson says: “We realized it’s a very competitive landscape. Other event managers were also very good, and the largest funds were in the $20 billion-plus range. I realized if I was to move up, it would have to be through performance—but performance that could be achieved without taking undue risk. There was no reason to jeopardize this fabulous business we had created and our track record just to grow bigger.”

So he went in search of low-risk, high-return investments that would give the fund the boosts they needed to enter the top brackets.

One of the unique skills that Paulson had developed through his career was in shorting bonds. He first practiced this strategy while at Gruss Partners in the early 1990’s when it shorted the bonds of bank holding companies that were at risk of a downgrade or of failing. The holding companies’ bonds were particularly vulnerable to a decline. Unlike the operating company bonds, which had direct access to the assets as collateral, the holding company’s primary asset was the equity in the operating company, which would almost always be wiped out in the event of insolvency.

The attraction of shorting bonds is the asymmetrical nature of the returns. If you could short a bond at par or close to par at a tight spread to Treasuries, then the downside would be limited if you were wrong, but the upside could be substantial if the company defaulted. The trick, though, was in finding mispriced credit that traded at par, which could default. This is no easy task. In addition to banks with two-tiered capital structures, Paulson also found opportunities in other financial companies with a holding company structure, such as insurance companies, and in leveraged buyouts. Almost all investors hated shorting bonds because most of the time the bonds paid out, and the negative carry from paying the interest on the short bond was a drag on performance.

Paulson had not been dissuaded from this challenge. He liked the asymmetrical risk/return potential, and continued to pursue this area as an investment strategy with periodic success over time.

By the spring of 2005, Paulson became increasingly alarmed by weak credit underwriting standards and excessive leverage being used by financial institutions. Credit quality had deteriorated to the point where the worst-performing companies could readily raise financing. And banks had fostered this trend by adding vast quantities of credit assets to their balance sheets and by increasing their leverage. When measured against common equity, the largest banks had leverage ratios of 30 to 40× and in some cases 50×. With that type of leverage, it wouldn’t take much for a loss to wipe out the equity, and with the credit quality deteriorating as it was, this appeared increasingly likely.

At the same time, as credit markets were spinning out of control, Paulson also felt the residential real estate market could be in a bubble. Prices had gone up rapidly and continuously for an extended period, and almost everyone was euphoric about the easy money to be made in housing. Paulson’s own home in Southampton, purchased at a bankruptcy auction in the last real estate downturn in 1994, had appreciated six times in value by 2005, well in excess of the long-term growth rate on home prices. Furthermore, John didn’t adhere to the theory that residential real estate prices only went up, having experienced previous real estate downturns.

The bubble nature of the real estate market, the frothiness of the credit market, and Paulson’s focus on shorting bonds led Paulson to investigate short opportunities in the mortgage market. While Paulson had no previous experience in the mortgage market, he knew it was the largest credit market in the world, larger at the time than the U.S. Treasury market. He asked Paolo Pellegrini and Andrew Hoine, two analysts at the firm, to take a look at the structure of the mortgage market.

Paolo quickly came back and said there were prime, midprime, and subprime segments. “Since we were interested in shorting, we decided to focus on the subprime segment,” explains Paulson. “Although the smallest of the mortgage segments, the market was so large that there was over a trillion dollars of subprime securities outstanding. When we dived deeper into the residential real estate market, the subprime market, and the securitization market, we began to believe that this area could implode.”

At that point, Paulson asked Paolo to focus exclusively on subprime securities. Paulson began to suspect that shorting credit could be the strategy that could give him the outsized performance he was looking for without taking excessive risk. Slowly, Paulson and his team were able to piece together how housing prices, and the trillion-dollar market built around them, were doomed to collapse like a house of cards. This gave Paulson the green light to begin purchasing protection through credit default swaps on debt securities he felt would decline in value due to weak credit underwriting.

The subprime mortgage securitization market was uniquely suited to buying credit protection. The typical subprime securitization was divided into 18 tranches, ranging from “AAA” to “BB,” with each lower tranche subordinate to the one above. The “BBB” tranche traded at par with a yield of about 100 basis points more than U.S. Treasuries. On average, they had only 5 percent subordination and were only 1 percent thick, meaning a loss of 6 percent in the pool would wipe out the “BBB” tranche. “In other words, by risking a 1 percent negative carry, we could make 100 percent if the bond defaulted,” says Paulson. “That was the precise asymmetrical investment we were looking for. We would lose very little if we were wrong, but could make a 100:1 return if we were right. And given the low quality of subprime loans and the deteriorating collateral performance, we thought the probability of success was very high. Yet, the credit markets at the time were in such a state of exuberance and the global demand for ‘BBB’ subprime securities was so strong that we could buy protection on virtually unlimited quantities of the securities.”

In the end, Paulson bought protection across his funds on about $25 billion of subprime securities. As spreads widened, and the value of those securities fell, Paulson and his team cashed in at an increasingly accelerated pace. Paulson & Co. had amassed $15 billion in profits off these trades by the end of 2007 with the Paulson Credit Fund up 600 percent that year. The firm’s assets under management grew from a respectable $6.5 billion in 2006 to a monstrous $28 billion by year-end 2007.

Paulson’s credit fund returned 20 percent, 30 percent, and 20 percent in 2008, 2009, and 2010, respectively. Paulson liked the neighborhood. “I think I always wanted to be in the top bracket,” he says. “I never imagined we’d get this big but I always liked and aspired to be successful. You can have a goal. You can try. But, you know, at the end of the day unplanned things can happen, too. I had a broad tool kit in the event area: mergers, bankruptcy, distressed, restructurings, which we could apply from either a long or short perspective. I had a great deal of experience working with a lot of brilliant people—Leon Levy, Ace Greenberg, and Marty Gruss—and had seen a lot of great investments including 100-to-1 investments.”

In its year-end 2010 investor letter, Paulson & Co. acknowledged that the fund participated as the lead or one of the lead investors in 10 of the top 14 bankruptcies, highlighting that because of its size and expertise, it was invited by numerous corporate management teams to provide capital on favorable terms to repay debt, strengthen equity, and/or restructure their balance sheets.

While most of the deals Paulson & Co. take on are intricate enough to warrant outsized returns, some stand-alone event-arbitrage investments are so treacherously complex, they brought the firm high prestige and enormous profits in their own right.

Mispriced Risk: Dow/Rohm & Haas

On February 4, 2009, in a letter addressed to Andrew N. Liveris that was made public, Paulson urged Dow’s chief to complete the $15 billion acquisition of the nearly hundred-year-old specialty chemical manufacturer Rohm & Haas. Their agreement had been made on July 10, 2008. Between June 30 and September 30 of that year, Paulson bought 15 million shares of Rohm & Haas, according to documents filed with the SEC, at which time the investment was worth $1.05 billion. Since then, numerous obstacles had delayed the deal, and a significant amount of Paulson & Co.’s wealth was on the line. Paulson was doing everything he could to encourage Dow to execute.

Paulson feels it is easy to compute returns from a spread, but his and his team’s expertise comes into play when evaluating the risk-return trade-off for a deal in trouble.

Deal completion risks are exacerbated when the economy and market weaken. When the economy slipped into a deep recession after Lehman failed, Dow found that the price it had agreed to pay for the company was too high and it wanted to exit the transaction. The spread went from $2 when the deal was announced to $25 as the stock fell to the low 50s. This raises the legal question for investors: can Dow exit the transaction? Luckily for Paulson, his years of experience in mergers and acquisitions gave him a leg up on the market in answering that question.

But even having read and having negotiated scores of them, Paulson wouldn’t consider himself an expert on merger agreements. This is where Michael Waldorf, a Harvard-educated merger lawyer, comes into the picture. “He had the perfect background that I wanted: an expert lawyer to understand all the nuances in various merger agreements,” says Paulson. “Dow was saying, ‘Oh, the economy had changed.’ It was a very different environment than it was when we announced this in June. Rohm & Haas’s earnings fell dramatically. There was a material adverse change in the business. And Dow actually sued Rohm & Haas in Delaware to void the merger agreement.”

In this case, a firm needs to be an expert in Delaware law in order to get involved and understand the legalities. Paulson & Co. is an expert, having observed or been a part of any significant merger agreement that has been litigated in Delaware. Paulson credits this know-how, from having his own attorneys at the courthouse to knowing the judges and their propensity to rule in Delaware court, as being a big part of his competitive advantage. He says: “We can make an estimate . . . with relatively high probability of what the outcome of that lawsuit will be. That is an extremely valuable skill. It’s a very narrow, very focused skill that very few organizations have.”

After closely reviewing the agreement, Paulson & Co. concluded that Dow did not have a case. Based on this background and analysis, Paulson & Co. insisted there were no fundamental obstacles to completing the deal and suggested several financing options that could make both sides content. But Dow continued to back away from its bid to buy Rohm & Haas, asserting that current economic conditions made it impossible to close “without jeopardizing the very existence of both companies.”

Paulson’s team saw that the agreement featured a material adverse change clause, but they felt the fact that Rohm & Haas’s earnings decline since they announced the deal was not a material adverse change. The deal was not dependent on Rohm & Haas’s earnings, and the fact that the economy had dipped into a recession was not a condition of the merger agreement. Paulson repeats: “The fact the stock market fell was not a condition. The fact that Lehman fell was not a condition. The fact that Dow was no longer making money, or that Dow may not be able to raise financing was not a condition to the merger agreement.” Only fraud would apply as a material adverse change, and there was no fraud. Dow had no out.

Why was it such a tight merger agreement? The attorneys representing Rohm & Haas were the best in the merger business: Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz. Says Paulson: “Generally, you don’t know you have a good attorney until you run into a problem.”

When Dow signed the merger agreement, there were no apparent problems on the horizon for the two strong companies. Even though Bear Stearns had fallen just months earlier, earnings at both companies were still growing, and the firms mistakenly felt that the economy would continue to grow.

That was in June 2008. By January 2009, the picture had changed completely. But by then Rohm & Haas was already protected by an agreement that allowed no wiggle room. Paulson says: “There was a steel door that didn’t allow you to get through. And these steel doors were put in place when no one was even thinking you needed any protection. That’s why Wachtell’s so good at what they do.”

Because there had been another bidder who wanted to buy the company—the world’s largest chemical maker, BASF—Rohm & Haas was not looking for a contingent transaction but an ironclad deal. With BASF hovering nearby, Dow agreed to Rohm & Haas’s terms. And at the time, Dow wasn’t overly concerned about the economy.

When searching for investments, Paulson & Co. looks for situations in which the risk is being mispriced. In the Dow/Rohm deal, Paulson & Co. was very confident in its assessment of the legal risks, which led it to take a large position. However, Paulson says: “What we overlooked or what we didn’t pay enough attention to was not the legal ability of Dow to exit the transaction but ultimately Dow’s ability to consummate its financing.”

To fund the acquisition, Dow had a $2.5 billion investment from Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway in convertible preferred, and $2.0 billion in preferred from Kuwait Investment Authority. It was also going to sell its joint venture business to Kuwait to fund the balance of the transaction. If, for whatever reason, the Kuwaiti deal fell apart, Dow had negotiated a safety net: a term loan from banks to bridge the facility. It seemed to Paulson that Dow was adequately protected.

Even when Kuwait did ultimately back out of the agreement and Dow sued them, Paulson had little expectation for Dow to succeed. The team had already looked into whether Dow had any legal right to force Kuwait to uphold its end of the bargain. It turned out it had only signed a letter of intent, so Paulson didn’t expect Dow to go through with suing Kuwaitis in a Kuwaiti court. And he was right. Dow had no choice but to drop the suit.

Despite this, Paulson knew that Dow had a backstop. The banks that committed to fund the deal had accepted a commitment fee from Dow, which would make it very difficult for them to back out on providing the financing. If they did, those banks could be liable, depending on the terms of that commitment, for the entire amount of the Rohm & Haas transaction. But in an extraordinary crisis like the one facing the financial system in late 2008, the banks were dying to get out of any and every financial commitment they could. The last thing they wanted to do was fund what could be a failing combination, because by the fourth quarter of 2008, both Dow and Rohm & Haas were no longer making money. If Dow had to borrow money to buy Rohm & Haas, they could go bankrupt.

Because Dow stock in January had fallen from $55 when they announced the transaction down to $6 a share, bankruptcy was looking more and more likely. Every day, more companies were filing for bankruptcy. Lehman Brothers now was the largest bankruptcy in the world. In January 2009, LyondellBasell—one of the largest chemical companies in the world, with $18 billion in debt—filed for bankruptcy as well. And all those same banks were debt holders. And those banks were trading for 40 cents on the dollar.

However, in the bank commitment letter, there was a back door. As a condition of funding, Dow Chemical needed to have an investment grade rating at the time of the drawdown. And in the midst of the crisis, Dow’s earnings turned into a loss and its sales had plummeted. Moody’s had downgraded Dow to triple B minus on negative watch, one notch above junk.

If Moody’s downgraded Dow to junk, the banks could walk away. Dow would not be able to complete the transaction. It would likely lose in Delaware court and be forced into bankruptcy. Moody’s, in its meeting with Dow, said unless Dow raised $1.6 billion of equity and reduced the term loan by $1.6 billion, it would downgrade Dow to junk.

One week before the court case, Paulson met with Dow and its bankers and told them that if they needed equity to complete the transaction, Paulson & Co. would consider investing in Dow to help it finance the Rohm & Haas deal. He says: “There were not too many people around willing to buy equity in Dow Chemical, when their stock was at six and other chemicals were filing for bankruptcy and the world was falling apart. But we said we would be willing to buy a preferred stock.”

If Paulson was going to get involved in such a risky investment he would only buy preferred stock, giving him seniority in the capital structure. When Paulson & Co. structured the preferred, its expertise in capital structures came in to play. “We had to invent a preferred that would give us the protection we wanted and allow Moody’s to consider it equivalent to common equity,” says Paulson. “We came up with what’s called a deferred dividend preferred—a preferred that does not pay cash dividends but pays dividends in additional shares of preferred. Since there was no cash requirement, a deferred dividend preferred could be considered equivalent to common equity in terms of supporting the debt above it.”

Paulson didn’t care whether he got dividends in cash or additional shares of preferred, just as long as he was senior to the common. But the next issue became the ranking of the new preferred relative to the existing preferred outstanding. The company proposed the new deferred dividend preferred would be senior to the common, but junior to the existing preferred outstanding, which was owned by Berkshire Hathaway and others.

Paulson knew that if he were junior to the existing preferred he could get wiped out in the event of a bankruptcy. But if he was pari passu with the existing preferred, the total preferred class would likely become the new common class. So he decided that as long as he could be on equal footing with existing preferred holders such as Buffett, he’d invest. “I don’t mind being in that position with Buffett,” Paulson explains, “where in the event of bankruptcy we’re both on the same side. And also, I said, ‘As long as you’re paying the dividend on our preferred in additional shares of preferred and not paying in cash, then no other preferred can get cash dividends.’ That, combined with the 15 percent dividend rate, created an overwhelming incentive for them to redeem the preferred once financing markets improved.”

In the end, Paulson’s team was able to negotiate the deal for preferred stock, allowing Moody’s to give Dow equity credit for it. It also gave Paulson & Co. the protection it needed to collect a decent return on its money. Paulson & Co., together with the Rohm & Haas families, funded the preferred shares, which allowed Dow to maintain its credit rating, raise the bank financing, and close the acquisition.

On March 6, 2009, once the financing was locked in, Dow dropped the lawsuit and announced that it would close the deal on April 1, causing the Rohm & Haas stock to shoot up from $55 to $78 a share.

When the transaction closed on April 1, 2009, Paulson & Co. netted a $600 million profit in the Rohm & Haas stake, which was the most amount of money the fund ever made in a merger arbitrage transaction. Fortunately, the economy soon recovered, the credit and equity markets rallied and Dow was able to sell investment-grade bonds, redeem the preferred, and refinance the bank loans. While a harrowing experience for Dow, the acquisition was ultimately a success and Dow’s stock revived to a high of over $40 per share in 2011.

Jumping into the Deep End: Citigroup

About the time the Rohm & Haas/Dow deal closed, another exceptional event-arbitrage opportunity presented itself, this time in how-the-mighty-have-fallen financials. As the crisis picked up steam and it became clear which banks were saddled with billions of dollars in toxic assets and which were doomed to fail, the financial system was playing a dangerous game of doomsday musical chairs. On January 16, 2009, the U.S. Treasury Department triggered the TARP, which had been announced that past October as a part of the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008, by purchasing a total of $1.4 billion in preferred stock from 39 U.S. banks under the Capital Purchase Program. The same day, the U.S. Treasury Department, Federal Reserve, and Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) finalized terms of their guarantee agreement with Citigroup. About a month later, on February 27, Citigroup announced the U.S. government would be taking a 36 percent equity stake in the company by converting $25 billion in emergency aid into common shares. Citigroup shares dropped 40 percent on the news. In aggregate the aid provided to the bank totaled $45 billion.

Because banks are highly leveraged, it is crucial to thoroughly analyze their assets, as a small percentage loss can quickly wipe out the equity. During the financial boom, Citigroup made many speculative investments, particularly in collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), mortgages, derivatives and other types of structured products. When the value of these assets deteriorated, they took enormous write downs, which in turn required them to raise more equity. Investors lined up to purchase equity in Citigroup starting in October 2007 as they thought the decline in the stock price represented a good buying opportunity.

However, as the losses mounted and the write-downs increased, the stock price collapsed. Citigroup’s stock price fell from a high of $56 per share at the end of 2006 to a low of $1 per share in March 2009. Many early investors in Citigroup and other banks subsequently saw their investments either wiped out or severely diminished. As Paulson explained, referencing the lifeline TPG threw to Washington Mutual in the spring of 2008: “They put in $7 billion and they lost it all within six months. Investing in banks at the wrong time is very risky.”

Paulson & Co. stayed away from investing on the long side of any banks until after the government commenced the stress tests and put forth an accurate appraisal of how much capital the banks needed.

Paulson had been scrutinizing the industry closely since 2006. When Paulson’s team saw the first signs of the asset-backed security market falling, it tried to figure out which banks were most exposed to losses on these same securities. Paulson estimated the losses banks would take and then compared those losses to the common equity in each. Ranking them from high to low, the list revealed which banks were in the most trouble. “Fannie and Freddie were in the worst shape,” Paulson says. “We projected losses of 400 to 600 percent of their equity. But Lehman was also high on the list. We predicted they would fail, and Citigroup was at risk as well. Citigroup without government help would have failed like Lehman failed.”

However, commencing in the second quarter of 2009, we sensed a turning point in bank valuations. Bank stocks were oversold and, due to the write-downs and capital raising, were unlikely to fail. We ranked the top 50 banks by the return potential and started acquiring bank stocks with the most potential upside.

Paulson & Co. quietly bought its initial 2 percent stake, or 300 million shares, in Citigroup in the third quarter of 2009. “Citigroup has some very valuable franchises. It’s the most global of the large U.S. banks. It has the largest U.S. banking operation in emerging markets, where the growth is. They have very good capital markets businesses, a valuable regional banking franchise, as well as a global transaction services business, which is almost unparalleled in banking anywhere in the world. So when all of those came together, it made Citigroup a very attractive situation.”

In buying Citibank, Paulson & Co. primarily bought preferred stock, which they then converted into common at a cost of around $2.50 a share. “We felt that once the government preferred and the existing preferred was converted into common that there wouldn’t be a need for additional common equity. We felt at that point we could invest without fear of further dilution.”

By the fourth quarter of 2009, Paulson upped his bet on Citi to over 500 million shares according to SEC filings. But by the end of the third quarter, Paulson & Co. trimmed its holdings to 424 million shares. “It’s not a reflection on our view of the stock specifically,” says Paulson, “but we have size limitations in our funds. As the share price doubled from $2.50 per share to $5 a share, the position size grew to $2.5 billion. That became too big for our portfolio. We pared that position down to keep the weighting in the portfolio below 8 percent as we don’t want to be too concentrated on one name.”

Paulson acquired a second billion-dollar-plus investment in a bank that received government bailout funds during the credit crunch. He had acquired 168 million shares of Charlotte, North Carolina–based Bank of America Corporation in the second quarter of 2009.

Paulson and his team then realized they were underweight in other banks with similar strong upsides like Wells Fargo and Capital One. They decided to further scale back on Citigroup and Bank of America, and increase their position in Wells Fargo and Capital One. But Paulson made the decision to keep the total allocation the same, just shifting the financials portion to other names to “broaden out the portfolio.”

In January 2011, Paulson & Co. reported its stake in Citigroup gained 43 percent, earning it over $1 billion in gains since initiation in mid-2009, according to Paulson’s 2010 year-end letter to investors, and was the largest position in their flagship Advantage funds.

Though they continued to reduce their position, reportedly down to 414 million shares as of February 2011, Paulson and his crew see much upside potential over the next two to three years, particularly if Citi’s losses continue to decrease and earnings grow. “Growth in the rest of the bank plus the elimination of the negative drag on those earnings from the legacy portfolio should allow Citi to make good profits,” he says. “When you convert these profits into a per-share estimate and then apply a modest multiple to those earnings, you could see somewhere between 50 and 100 percent upside in Citigroup’s stock over a two- to three-year period.”

At the time, it was one of Paulson’s most successful investments. “The Citigroup trade was very complicated,” Paulson says. “People were afraid to invest. People that invested early lost a lot of money and they wouldn’t invest any more. The valuation was low. We were correct to assume the government recap plan was the right plan and that would be the last capital they needed. We thought that the valuation of Citigroup was well below what it would have traded at on a normalized earnings multiple, and that it was the most discounted of all the banks. We did the analysis on the banks with the most return potential and Citigroup came out on top.”

Paulson & Co. initiated a gold share class for all of its investors in April 2009. Paulson says, “Of all the investments we made in all the bankruptcies, all the events, all the mergers, etc., the single most important investment I made was switching to the gold share class.” While the holdings of each portfolio would mirror those of the other Paulson funds, the investments would be denominated in gold as opposed to dollars, allowing for investors to benefit from both the expected rise in value of the portfolio as well as the expected rise in the value of gold versus the dollar over time. Investors that opted for the gold share class earned any dollar returns, plus any incremental returns in the appreciation of gold versus the dollar.

In 2009, Paulson and his credit team were closely monitoring government actions to stimulate the economy and aid the recovery. When the Fed adopted quantitative easing as a tool for monetary stimulus Paulson became concerned about the potential for future inflation and dollar depreciation.

Quantitative easing historically had not been used in the United States and was a very unorthodox monetary tool, but the United States had entered into a financial crisis that was deeper than any since the Great Depression. And it required innovative and unusual thinking in order to stem the crisis and return the country to recovery. “Due to our concerns about the dollar, we started to look for another currency in which to denominate our investments,” says Paulson. “But in our search, we found other countries, such as the United Kingdom, were also printing money, and we had separate concerns about the stability and long-term viability of the euro. We thought that, given all the uncertainties regarding paper currencies, gold would be the best currency.”

He stresses, however, that gold as a currency has a three- to five-year time horizon. “Gold is very volatile in the short term and could as easily go down in the near term as go up. But if you’re invested over a three- to five-year horizon, I think you’d be much safer in gold as a currency rather than the dollar.”

A Little Help from His Friends

Paulson is the first to tell you he gets by with a little help from his friends. Over the years he has benefited from sage advice from influential advisors to the fund, one of whom is a rather famous former chairman of the Federal Reserve.

In the spring of 2007, Deutsche Bank’s global head of investment banking, Anshu Jain, threw a dinner in the firm’s executive dining room on the forty-sixth floor of 66 Wall Street. The dinner was hosted by special adviser to the bank Dr. Alan Greenspan, and the guest list comprised a selective group of the firm’s biggest trading clients. Among those invited were Paulson, Bruce Kovner of Caxton Associates, Henry Swieca of Highbridge, Israel “Izzy” Englander of Millenium Partners, and Boaz Weinstein, the firm’s hot-shot head of credit-focused proprietary fund Saba Capital. Anshu’s department historically generated 70 to 80 percent of the firm’s profits and these relationships needed to remain intact.

Dr. Greenspan at the time said he’d take on only three clients when he retired from the Fed. He already had two: one was a bank, Deutsche Bank; another an asset manager, PIMCO; and the third would be a hedge fund. “I met him at that dinner, we got along well, and he said he would consider taking on one more client. We were fortunate to be that client.”

Before Greenspan joined the advisory board in January 2008, Paulson admits that he did not have a good understanding of how the monetary system works, what the Fed does, or how money is created. “I was very focused on individual companies and had never looked at a Fed balance sheet,” he admits. “I didn’t know what the monetary base was or what money supply was. I didn’t know the relationship between the Fed and other banks nor their relation to the Treasury.”

Once a month or so, Dr. Greenspan flies up for the day from D.C. with his director of research, Katie Broom, to attend meetings with Paulson in New York, where they spend the day discussing current monetary policy and economics with regard to the portfolios. They often have a lunch of Diet Cokes and turkey sandwiches together at the Paulson & Co. offices. “When the financial crisis started to evolve, the government was a very important player in the restructuring of the financial system, so I really wanted to learn how the system worked,” says Paulson. “I couldn’t have found a better adviser than Dr. Greenspan for that.”

Says Dr. Greenspan, “John Paulson has an uncanny ability to judge relative risk, and to capitalize on such judgments. He may slip from time to time—we all do. But with the discipline he brings to investments, continued success is far more likely than not.”

As another record year ended and he sent out his annual 2010 letter to investors, Paulson announced he’d begin hosting various fund-specific conferences for investors in addition to his June and November reviews and workshops. Though Paulson & Co. did see some redemption, on the whole investors were quite pleased. At the end of 2010, LCH investments conducted an independent study of hedge funds that produced the greatest net gains for investors since inception. It ranked Paulson & Co. number three, behind only George Soros’s Quantum Endowment Fund (started in 1973) and Jim Simons’s Renaissance Medallion Fund (started in 1982). In his 2010 year-end letter to investors, Paulson proudly included a graphic that listed the top 10 managers, stating, “We are proud that we are number three on the list with over $28 billion in net gains, even though we started our funds 12 and 21 years after Renaissance and Quantum, respectively.”

In 2011, Paulson’s strategy had shifted to one that emphasized long restructuring investments. As Paulson said, “No one strategy is correct all the time. We shifted from short credit in 2007, to short equities in 2008, to long credit in 2009 and 2010, to now long restructuring equities. We believe at this point in the economic cycle the greatest gains will come from post-reorganization equities and companies that came close to bankruptcy but were able to raise equity or otherwise restructure capital structure to avoid bankruptcy.”

Paulson’s bank investments fit this strategy, as do his investments in insurance companies, other financial firms, hotels, select automobile companies, and other industrial companies.

A stakeholder in both MGM Resorts and Caesar’s Entertainment, both acquired via restructurings to increase equity and reduce debt, he held the Advantage Funds meeting in Las Vegas in April to showcase those investments. In addition, Paulson held his annual midyear workshops in Paris this year, instead of the customary London, to highlight the importance of Paris as a financial center. Carlos Ghosn, CEO of Renault—another large Paulson & Co. position—kicked off the all-important opening dinner ceremony.

Last year’s meeting was more uneasy than the past. While the Advantage funds started the year in positive territory, by June they had drifted to a loss. A loss in the flagship fund following recent news of fraud by the Chinese paper manufacturer Sinoforest had been splashed across the papers for the past week. Paulson originally invested in the company on the basis of it being an acquisition candidate, as well for the potential that the company would relist from the Toronto Stock Exchange to either Hong Kong or Shanghai, where it would receive a higher valuation. Paulson & Co. had issued a brief letter to all investors explaining the origination of the position and the actual size relative to the portfolio: two percent. Still, there were many outstanding questions. It was time for Paulson to reassure investors face to face. He was the largest investor in the Advantage funds, after all.

When asked about Paulson’s position in Sinoforest, his former boss Ace Greenberg said: “People seem to be making a big deal about this but they are not giving him enough credit. You can’t fly with the eagles and poop with the canaries, as I said to a newspaper reporter once. It’s a relatively small position in a very big fund. One of the things that makes investing difficult is that you are relying on management to have the same ethics and principles as you do.”

Despite some short-term setbacks, the mood was overall jovial. Paulson & Co. had made the people at this conference a lot of money. Some of Paulson’s longest investors and dearest friends had come to this meeting. Back in London a week or so later, Paulson called his friend Rick Sopher. Sopher is the Managing Director of LCF Edmond de Rothschild Asset Management Ltd. and Chairman of three investment vehicles, which are fully listed on the Euronext Exchange. They include Leveraged Capital Holdings, the first multimanager fund of hedge funds, which was launched in 1969. He has a senior role in the Edmond de Rothschild Group that had been responsible for deploying over $10 billion in investments all over the world and was a big player that had purposely stayed under the radar.

After a busy couple of weeks, Paulson was looking forward to a relaxing dinner with his good friend. But a few of London’s power players had already heard that Paulson would be in town and were asking for an introduction. Instead of a quiet evening, Sopher organized a dinner for Paulson at Spencer House at the bequest of Lord Rothschild, inviting London’s finest dignitaries and investing elite.

“When John travels now, the world’s most impressive names clamor for the chance to meet with him, see what he’s all about,” Sopher says. LCH had started investing with Paulson & Co. in 2006. They had identified problems in the credit markets but were having difficulty finding suitable investments to capitalize on the downside opportunity. When LCH came across Paulson & Co.’s research, it knew it had found a like-minded firm and joined forces.

Though Sopher was a believer in his strategies from the beginning, he notes the significant change in his countrymen’s perception of John Paulson. “This wasn’t the story a few years ago,” he said. “It’s really quite incredible. John is undoubtedly one of the greatest investors of all time.”

But an unexpectedly high degree of global economic uncertainty can betray even the most methodical strategies and well-positioned investors at certain points in time. The continuing weakness of the U.S. economy and fiscal standing, headline inflation risk, and the subsequent downgrade of the U.S. credit rating to one notch below “AAA” for the first time in history all applied intense pressure on the markets. Combined with the European debt crisis and the potential fallout from all of the underlying exposures across the globe, it manifested huge swings of volatility during the summer of 2011, sometimes by as much as over 500 points a day in the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

Paulson & Co., like most other funds, weren’t immune to the instability, which threw the fundamentals of some of their core positions off target. In his third quarter letter to investors, Paulson apologized for the fund’s year to date 2011 performance, acknowledging it was the worst in the firm’s 17-year history. “We are disappointed and apologize for these results,” the letter started. “We have learned from the 2011 experience and are committed to returning investors to their high water marks and to producing above average returns for the long term.”

Says Paulson, “Volatility in our portfolio in 2011 was caused by macroeconomic events that negatively effected capital markets, such as the Standard & Poor’s downgrade of the United States’ credit rating and sovereign debt issues in Europe. Despite this, many event plays across our portfolio have been performing at record levels in terms of earnings, but have not yet been rewarded by the marketplace, resulting in portfolio losses.”

Paulson would also go on to concede that the firm’s expectations for economic growth were overly optimistic coming into 2011, causing them to position the funds for a strong economic rebound. When global markets fell sharply midyear, Paulson & Co. was hit particularly hard given the economically sensitive nature of some of their holdings—including bank stocks. Bank of America, another prominent position that Paulson & Co. had been steadily reducing over the past year but was still a meaningful holding, continued to face headwinds from mortgage problems and related lawsuits.

In Paulson’s third-quarter letter to investors, he addressed his outstanding banking sector exposure as well. “Despite the negative perception of the banking sector and the considerable difficulties faced by Bank of America, three of these banks in our portfolio, Wells Fargo, J. P. Morgan, and Capital One have reported record trailing 12-month earnings as of 3Q 2011,” said Paulson. “These banks have high capital levels, strong operating earnings, and high reserves. The strength of their earnings in this unfavorable environment highlights the potential for profits in a better economic environment.”

Hewlett-Packard, the world’s number one PC vendor by unit shipments and another position in the flagship Advantage funds, took a big hit mid-August on the announcement that it would be considering shedding the PC business and discontinuing its line of handhelds to focus on higher-margin businesses. In response to shareholder anger over the company’s puzzling moves, Leo Apotheker, CEO of Hewlett-Packard for just 11 months, was ultimately ousted and replaced by former eBay CEO Meg Whitman. The company later reaffirmed its commitment to the PC business.

Paulson’s main Advantage funds ended the year down 36 percent with the gold share class of the same fund losing 24 percent. With losses incurred across most of his other funds as well, assets dropped to approximately $25 billion by the end of 2011. To help the firm better analyze macroeconomic conditions going forward, Paulson & Co. added on Martin Feldstein, President Emeritus of the National Bureau of Economic Research, to their Economic Advisory board.

“Entering 2011, I thought we had a positive macro outlook that gave us the confidence to increase our net exposure,” Paulson explains back in his office in mid-December as we reflect on the year. “In retrospect, we were too overconfident with this scenario and the macro risks effected the market and our overall portfolio. Though the draw downs have been more extreme than we are used to, as fear subsides, we believe our positions offer great upside and are poised to outperform,” he says.

Even though the losses of 2011 were extreme, Paulson is optimistic he can gain significant ground in the year ahead. “I continue to believe the equity market is oversold for several reasons,” he starts. “For one thing, price-to-earnings ratios are at historic lows, which has created great buying opportunities where companies are trading at extremely low valuations irrespective of strong performance,” he says. “Moreover, the discrepancy between earnings yields and Treasury yields is at an all time high,” he adds, noting the further discounts the market has been pricing in. He explains. “The dividend yield of the S&P 500 exceeds that of 10-year Treasuries, even though equity dividend yields grow over time while treasury yields are fixed,” says Paulson.

“Similar fear-driven periods in the past have been used as buying opportunities for savvy investors. Unfortunately, many investors make the mistake of buying high and selling low while the exact opposite is the right strategy to outperform over the long term,” he explains.

For all of last year’s losses, Paulson & Co. started 2012 on an encouraging note with all of the funds in positive territory for the month of January. The merger arbitrage fund, Paulson Partners, closed the month up 2.34 percent and Paulson Enhanced, 4.84 percent. The fund’s flagship Advantage funds were up 3.95 percent with the levered Advantage Plus up 5.4 percent. The Paulson Gold fund gained 13.4 percent with the gold share classes for the respective funds outperforming the dollar share class by an additional 4 to 6 percent across the board.