Chapter Seventeen

Ethical Considerations

- Introduction

- Introductory Case Study: Political Contributions

- Ethics and Engineering

- Codes of Ethics

- Ethical Decision-Making Framework

- Case Study

- Corruption

- Outro

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define engineering ethics.

- Apply the ASCE code of ethics to ethical decisions.

- Compare and contrast ethical situations that students face to situations faced by practicing engineers.

- Summarize, from memory, the seven Fundamental Canons of the ASCE Code of Ethics.

- Define corruption and list various types of corruption.

- Describe the negative effects that corruption has on society.

Introduction

The study of engineering ethics is the study of “moral values, issues, and decisions involved in engineering practice” (Martin and Schinzinger, 2004). In even more simple terms, engineering ethics is knowing what you ought to do, and doing it.

Engineers are among the most respected and trusted members of society. This claim is based upon numerous public opinion polls that rate engineers as much more trusted than many other professions. This trust and respect has been earned over many years, thanks not only to the profession's contributions to increased quality of life, but also to the ethical behavior of the vast majority of practicing engineers.

For many of the ethical choices with which you are faced, the separation between right and wrong will be quite distinct; that is, the decision will be a matter of choosing between black and white. Of course, this does not infer that the choice will be an easy choice for you. For example, you may be inspecting a job site and be asked to “look the other way” as the contractor uses substandard materials or methods. Or, you may fail to save a spreadsheet of collected data, and to cover up your mistake, you might be tempted to fabricate data. In each of these cases, the ethical decision is relatively easy to identify but not necessarily easy to implement.

On the other hand, for many ethical decisions, it is much more difficult to differentiate between right and wrong and you will be faced with making choices in the “gray” area. For example, perhaps you own some unimproved land and are involved with an infrastructure construction project that will potentially bring utilities (and therefore add value) to your land—what should you do about this potential conflict of interest? The introductory case study also presents a situation in which the right thing to do is not immediately obvious.

Is this chapter a waste of time? In other words, is it possible to “teach” students to be ethical? Instructors cannot make students act ethically; indeed, some people simply do not respect or observe the norms of ethical behavior. Rather, the goal of this chapter is to ensure that you know what ethical behavior “looks” like and where to find guidance to help you make ethical decisions. Then, we hope you will choose to act ethically in your future work.

Introductory Case Study: Political Contributions1

Engineers from a variety of engineering firms were invited to participate in a fundraising barbeque held by the deputy secretary of the state Department of Transportation (DOT) for the governor's re-election campaign. Some of the engineers were designated as “sponsors” because they gave $250, $500, or $1,000 at the fundraiser. Among the individuals invited were a number of engineers who work for engineering companies that do business with the state DOT. When questioned, the engineers indicated that their contributions would have no bearing on their firm's selection to do business with the state. At the time of the fundraiser, some of the firms were in the process of negotiating contracts with the state DOT. The deputy secretary of the state DOT has no role in approving engineering contracts. This situation begs the question: was it ethical for the engineers to participate in the fundraiser?

Ethics and Engineering

You should note that many of the ethical challenges faced by practicing engineers are very similar to the challenges faced by engineering students. Table 17.1 compares a few of those challenges. Many more examples exist; indeed, most likely every ethical decision with which a student is confronted has a corresponding ethical decision in the “real world.”

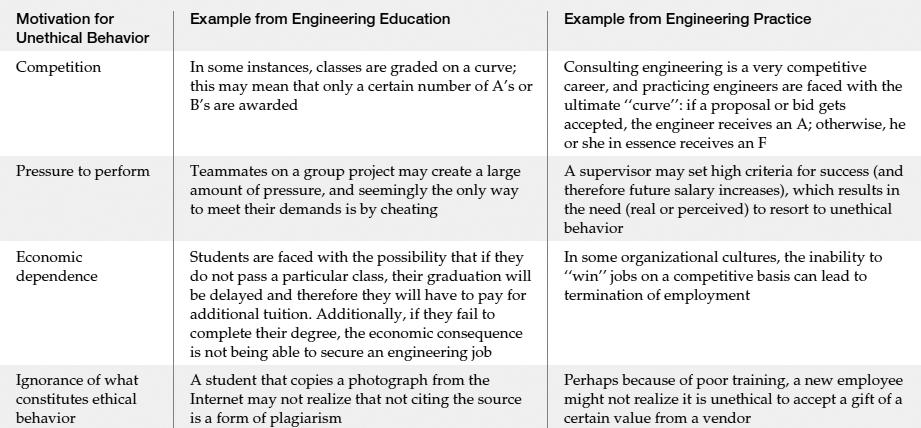

Nearly every unethical decision can be justified by the person carrying out the decision. And just as the unethical decisions are similar for student and practicing engineer, so are the motivations and justifications for the unethical choice. Table 17.2 provides motivations for unethical behavior and illustrates how they might apply to both practicing engineers and students. The reasons (or perhaps excuses?) provided in Table 17.2, can be justified in a number of ways. Common justifications include “no one will find out about it,” “everyone else is doing it,” or “I'll only do it once.”

Ethics in Higher Education

As a student, you expect your university professors and administrators to act ethically. In October 2009, the Chancellor, the President, and several trustees of the University of Illinois Champaign-Urbana resigned amidst a scandal involving the special admission of students connected to university trustees, lawmakers, and other influential businesspeople.

“Get Out as Fast as You Can…”

At a commencement ceremony for the University of Michigan College of Engineering, Jerry Levin, Chairman and CEO of American Household, Inc. gave the following advice, “You must have the highest ethical and moral standards to succeed over the long term. Shortcuts are dangerous and eventually will place you in jeopardy. And if it becomes impractical to maintain your integrity, get out—get out as fast as you can.”

Table 17.1

Comparison of Unethical Behavior of Students and Practicing Engineers

| Unethical Behavior by a Student | Corresponding Unethical Behavior by a Professional |

| Copying a classmate's homework assignment | Copying and pasting a diagram from the Internet into a report without receiving permission or citing the source |

| Collaborating with a classmate on a take-home exam even though such collaboration is forbidden | Participating in bid rigging, in which bidders conspire among each other to “take turns” winning bids, thus removing competition from the bidding process and increasing cost to the project owner |

| Altering data obtained from a lab exercise, thereby ensuring that results appear to be as expected and that the lab work will not have to be repeated | Falsifying data in any number of ways; for example, overbilling a client for the amount of excavation that occurred or not constructing a below-ground utility properly and literally “covering up” the mistake |

Table 17.2

Examples of Motivations for Unethical Behavior

Codes of Ethics

In deciding what type of behavior is ethical, engineers can rely on codes of ethics for guidance. Codes of ethics are provided by nearly every professional engineering society. In this chapter we have included the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) Code of Ethics. This code contains four Fundamental Principles and seven Fundamental Canons. You should become very familiar with the Fundamental Canons. The majority of the code is devoted to providing guidance on each of the canons.

Code of Ethicsa

Fundamental Principlesb

Engineers uphold and advance the integrity, honor and dignity of the engineering profession by:

- using their knowledge and skill for the enhancement of human welfare and the environment;

- being honest and impartial and serving with fidelity the public, their employers, and clients;

- striving to increase the competence and prestige of the engineering profession; and

- supporting the professional and technical societies of their disciplines.

Fundamental Canons

- Engineers shall hold paramount the safety, health and welfare of the public and shall strive to comply with the principles of sustainable developmentc in the performance of their professional duties.

- Engineers shall perform services only in areas of their competence.

- Engineers shall issue public statements only in an objective and truthful manner.

- Engineers shall act in professional matters for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees, and shall avoid conflicts of interest.

- Engineers shall build their professional reputation on the merit of their services and shall not compete unfairly with others.

- Engineers shall act in such a manner as to uphold and enhance the honor, integrity, and dignity of the engineering profession and shall act with zero-tolerance for bribery, fraud, and corruption.

- Engineers shall continue their professional development throughout their careers, and shall provide opportunities for the professional development of those engineers under their supervision.

Guidelines to Practice Under the Fundamental Canons of Ethics

CANON 1

Engineers shall hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public and shall strive to comply with the principles of sustainable development in the performance of their professional duties.

- Engineers shall recognize that the lives, safety, health, and welfare of the general public are dependent upon engineering judgments, decisions and practices incorporated into structures, machines, products, processes and devices.

- Engineers shall approve or seal only those design documents, reviewed or prepared by them, which are determined to be safe for public health and welfare in conformity with accepted engineering standards.

- Engineers whose professional judgment is overruled under circumstances where the safety, health, and welfare of the public are endangered, or the principles of sustainable development ignored, shall inform their clients or employers of the possible consequences.

- Engineers who have knowledge or reason to believe that another person or firm may be in violation of any of the provisions of Canon 1 shall present such information to the proper authority in writing and shall cooperate with the proper authority in furnishing such further information or assistance as may be required.

- Engineers should seek opportunities to be of constructive service in civic affairs and work for the advancement of the safety, health, and well-being of their communities, and the protection of the environment through the practice of sustainable development.

- Engineers should be committed to improving the environment by adherence to the principles of sustainable development so as to enhance the quality of life of the general public.

CANON 2

Engineers shall perform services only in areas of their competence.

- Engineers shall undertake to perform engineering assignments only when qualified by education or experience in the technical field of engineering involved.

- Engineers may accept an assignment requiring education or experience outside of their own fields of competence, provided their services are restricted to those phases of the project in which they are qualified. All other phases of such project shall be performed by qualified associates, consultants, or employees.

- Engineers shall not affix their signatures or seals to any engineering plan or document dealing with subject matter in which they lack competence by virtue of education or experience or to any such plan or document not reviewed or prepared under their supervisory control.

CANON 3

Engineers shall issue public statements only in an objective and truthful manner.

- Engineers should endeavor to extend the public knowledge of engineering and sustainable development, and shall not participate in the dissemination of untrue, unfair, or exaggerated statements regarding engineering.

- Engineers shall be objective and truthful in professional reports, statements, or testimony. They shall include all relevant and pertinent information in such reports, statements, or testimony.

- Engineers, when serving as expert witnesses, shall express an engineering opinion only when it is founded upon adequate knowledge of the facts, upon a background of technical competence, and upon honest conviction.

- Engineers shall issue no statements, criticisms, or arguments on engineering matters which are inspired or paid for by interested parties, unless they indicate on whose behalf the statements are made.

- Engineers shall be dignified and modest in explaining their work and merit, and will avoid any act tending to promote their own interests at the expense of the integrity, honor, and dignity of the profession.

CANON 4

Engineers shall act in professional matters for each employer or client as faithful agents or trustees, and shall avoid conflicts of interest.

- Engineers shall avoid all known or potential conflicts of interest with their employers or clients and shall promptly inform their employers or clients of any business association, interests, or circumstances which could influence their judgment or the quality of their services.

- Engineers shall not accept compensation from more than one party for services on the same project, or for services pertaining to the same project, unless the circumstances are fully disclosed to and agreed to, by all interested parties.

- Engineers shall not solicit or accept gratuities, directly or indirectly, from contractors, their agents, or other parties dealing with their clients or employers in connection with work for which they are responsible.

- Engineers in public service as members, advisors, or employees of a governmental body or department shall not participate in considerations or actions with respect to services solicited or provided by them or their organization in private or public engineering practice.

- Engineers shall advise their employers or clients when, as a result of their studies, they believe a project will not be successful.

- Engineers shall not use confidential information coming to them in the course of their assignments as a means of making personal profit if such action is adverse to the interests of their clients, employers, or the public.

- Engineers shall not accept professional employment outside of their regular work or interest without the knowledge of their employers.

CANON 5

Engineers shall build their professional reputation on the merit of their services and shall not compete unfairly with others.

- Engineers shall not give, solicit, or receive either directly or indirectly, any political contribution, gratuity, or unlawful consideration in order to secure work, exclusive of securing salaried positions through employment agencies.

- Engineers should negotiate contracts for professional services fairly and on the basis of demonstrated competence and qualifications for the type of professional service required.

- Engineers may request, propose, or accept professional commissions on a contingent basis only under circumstances in which their professional judgments would not be compromised.

- Engineers shall not falsify or permit misrepresentation of their academic or professional qualifications or experience.

- Engineers shall give proper credit for engineering work to those to whom credit is due, and shall recognize the proprietary interests of others. Whenever possible, they shall name the person or persons who may be responsible for designs, inventions, writings, or other accomplishments.

- Engineers may advertise professional services in a way that does not contain misleading language or is in any other manner derogatory to the dignity of the profession. Examples of permissible advertising are as follows:

- Professional cards in recognized, dignified publications, and listings in rosters or directories published by responsible organizations, provided that the cards or listings are consistent in size and content and are in a section of the publication regularly devoted to such professional cards.

- Brochures which factually describe experience, facilities, personnel, and capacity to render service, providing they are not misleading with respect to the engineer's participation in projects described.

- Display advertising in recognized dignified business and professional publications, providing it is factual and is not misleading with respect to the engineer's extent of participation in projects described.

- A statement of the engineers' names or the name of the firm and statement of the type of service posted on projects for which they render services.

- Preparation or authorization of descriptive articles for the lay or technical press, which are factual and dignified. Such articles shall not imply anything more than direct participation in the project described.

- Permission by engineers for their names to be used in commercial advertisements, such as may be published by contractors, material suppliers, etc., only by means of a modest, dignified notation acknowledging the engineers' participation in the project described. Such permission shall not include public endorsement of proprietary products.

- Engineers shall not maliciously or falsely, directly or indirectly, injure the professional reputation, prospects, practice, or employment of another engineer or indiscriminately criticize another's work.

- Engineers shall not use equipment, supplies, laboratory, or office facilities of their employers to carry on outside private practice without the consent of their employers.

CANON 6

Engineers shall act in such a manner as to uphold and enhance the honor, integrity, and dignity of the engineering profession and shall act with zero tolerance for bribery, fraud, and corruption.

- Engineers shall not knowingly engage in business or professional practices of a fraudulent, dishonest, or unethical nature.

- Engineers shall be scrupulously honest in their control and spending of monies, and promote effective use of resources through open, honest, and impartial service with fidelity to the public, employers, associates, and clients.

- Engineers shall act with zero-tolerance for bribery, fraud, and corruption in all engineering or construction activities in which they are engaged.

- Engineers should be especially vigilant to maintain appropriate ethical behavior where payments of gratuities or bribes are institutionalized practices.

- Engineers should strive for transparency in the procurement and execution of projects. Transparency includes disclosure of names, addresses, purposes, and fees or commissions paid for all agents facilitating projects.

- Engineers should encourage the use of certifications specifying zero tolerance for bribery, fraud, and corruption in all contracts.

CANON 7

Engineers shall continue their professional development throughout their careers, and shall provide opportunities for the professional development of those engineers under their supervision.

- Engineers should keep current in their specialty fields by engaging in professional practice, participating in continuing education courses, reading in the technical literature, and attending professional meetings and seminars.

- Engineers should encourage their engineering employees to become registered at the earliest possible date.

- Engineers should encourage engineering employees to attend and present papers at professional and technical society meetings.

- Engineers shall uphold the principle of mutually satisfying relationships between employers and employees with respect to terms of employment including professional grade descriptions, salary ranges, and fringe benefits.

aThe Society's Code of Ethics was adopted on September 2, 1914 and was most recently amended on July 23, 2006. Pursuant to the Society's Bylaws, it is the duty of every Society member to report promptly to the Committee on Professional Conduct any observed violation of the Code of Ethics.

bIn April 1975, the ASCE Board of Direction adopted the fundamental principles of the Code of Ethics of Engineers as accepted by the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology, Inc. (ABET).

cIn November 1996, the ASCE Board of Direction adopted the following definition of Sustainable Development: “Sustainable Development is the challenge of meeting human needs for natural resources, industrial products, energy, food, transportation, shelter, and effective waste management while conserving and protecting environmental quality and the natural resource base essential for future development.”

Ethical Decision-Making Framework

When faced with an ethical decision, you should consider the following questions, which are based on the American Society of Civil Engineer's PLUS (Policies, Legal, Universal, Self) decision-making process:

- Does the action hold paramount the safety, health, and welfare of the public?

- Does the action serve the best interests of the client?

- Is the action consistent with the ASCE code of ethics?

- Is the action compliant with the letter and the spirit of applicable laws and regulations?

- Does the action satisfy your own personal definition of right, good, and just? Will you be able to sleep at night with your decision?

You should not make ethical decisions in isolation, and should share your concerns with trusted co-workers and friends. Be discrete in these discussions. Professional societies often have an ethics board or a help line to which you can ask questions in anonymity.

If your decision leads to having to report an activity or situation, use the proper chain of command when doing so. For example, if you are certain that a co-worker has falsified data on an environmental permit application, your first place to report this probably is not the state environmental protection agency, the local newspaper, or your Facebook or Twitter account. Rather, you may want to first discuss this unethical behavior with your direct supervisor.

In some (rare) instances, the ethical decision you are faced with may involve keeping your job or not. But walking away and “washing your hands” of the situation is not always the ethical choice either. In some cases, the ethical choice is walking away and at the same time reporting the unethical behavior to appropriate authorities. Few people want to be labeled a “whistle-blower,” and such actions are rare in engineering and should be considered a last resort; however, whistle-blowing may be the only ethical decision to make in certain situations.

Student Cheating

Some research has shown that engineering students are more prone to cheating than students pursuing degrees in other disciplines. This is likely due to many factors, the most significant of which are the demanding workload associated with engineering curricula and the competitive culture in some undergraduate engineering programs. In one study, 96 percent of engineering students reported that they had cheated at least once in one form or another (Carpenter et al., 2006). Forms of cheating included copying from someone else's homework, allowing one's homework to be copied, copying an old term paper, etc. These results are very disturbing, as other research has shown that cheating in school carries over to cheating in the workplace. That is, students that cheat throughout their undergraduate studies are more likely to behave unethically in the workplace. If such carryover occurs in engineering such that 96 percent of engineers behave unethically, the effect on the reputation of the profession will be disastrous.

Case Study

Case studies based on real ethical decisions can be very helpful in highlighting the fact that the ethical decisions associated with real situations are, rather than being black or white, often “gray.” Ethical decisions are full of competing variables, and ethical case studies help you appreciate this. For example, the engineer has to be an “agent” or trustee to the client, yet must abide by all regulations, while at the same time not forgetting that public welfare must be held paramount. The remainder of this section is the continuation of the Introductory Case Study and illustrates that some interpretation of the code is necessary in real situations. This case study refers to the National Society of Professional Engineers (NSPE) Code of Ethics, which is very similar to the ASCE Code of Ethics.

Ethical and related issues involving political contributions by individual engineers and firms has been an issue that the engineering profession has addressed and continues to address. The issue has a variety of facets, including the well-acknowledged need for professional engineers to become actively involved in the political process to affect legislative, legal, and regulatory policy. This need is contrasted with the perception of individuals and companies making political contributions with the expectation of, or at least in anticipation of, favorable consideration for future public engineering work. Clearly, this is a complicated issue with no easy solution.

Whistle-Blowing in Reality

The possibility of whistle-blowing is a very disconcerting proposition for practicing engineers. Consider the following situation, based on the reality in which a young engineer found himself. This engineer was working on a project that was running over budget. Rather than bill his hours to that project, his employer repeatedly required him to bill the hours to a different project that was under budget. As a result, work on the overbudget project was billed to a different client. This young engineer was faced with a dilemma; it was clear that this unethical practice was supported by company management, and that questioning the practice might lead to termination of employment. Ultimately, rather than reporting the activity to authorities (the “correct” but difficult choice of action), the engineer chose to find employment with another firm.

Online Case Studies

Links to several repositories of case studies are available on the textbook website

NSPE Board of Ethical Review Case Studies

NSPE Board of Ethical Review Case Studies

Numerical-Based Case Studies

Numerical-Based Case Studies

Center for the Study of Ethics in Society Website

Center for the Study of Ethics in Society Website

Online Ethics Center Website

Online Ethics Center Website

Over the years, NSPE has studied the issue in significant depth and taken a position to encourage all engineers to support political candidates who have demonstrated through their activities a commitment to ethical professional practices. NSPE cautions, however, that consistent with the NSPE Code of Ethics, that it is unprofessional for engineers, either on their own behalf or on behalf of their firms or employers, to make political contributions in the form of either cash or services in a manner intended to influence the award and administration of contracts involving a public authority, or which may have the appearance of influencing the award and administration of contracts involving a public authority. Therefore, consistent with its values, goals, and Code, NSPE:2

- Encourages, endorses, and supports the enactment of public disclosure laws, which identify political contributions to federal, state, and local candidates.

- Endorses the enactment of laws and rules, administered by state ethics and election commissions and professional and trade licensing boards, which are intended to assist candidates for public office and professionals in avoiding ethical and legal conflicts relating to political contributions.

- Endorses the establishment of state ethics and election commissions to monitor these laws in those states where such commissions do not currently exist, and advocates that state ethics and election commissions and licensing boards for all professions and trades be empowered to establish rules and limits for contributions.

Furthermore, NSPE endorses that these boards and commissions be empowered to establish penalties and take appropriate enforcement action against parties that fail to follow the requirements of the laws and rules.

It would appear that a $250 contribution or contributions in the range of $250 are well within the definition of nominal contributions to a state gubernatorial campaign and, therefore, clearly fall within what is acceptable under the language of the Code. Notwithstanding the facts and circumstances involved, it is difficult, if not impossible, to believe that a political contribution of this magnitude could create any expectation or other basis to affect the selection or receipt of future state or other engineering work. The board's view might be altered if there was some suggestion in the facts that there was a coordinated effort to have a large number of individuals from one firm make individual contributions to a candidate for public office, resulting in a large contribution from what would be perceived as a special commercial interest. However, those facts do not appear to be present in this case.

In conclusion, it was ethical for the engineers to participate in the fundraiser, given that (1) the contribution amounts were not excessive, (2) there was no linkage between the contributions and the selection of the firms for state work, and (3) the contributions are publicly disclosed.

International Corporate Ethics

The World Economic Forum publishes a biannual Global Competiveness Report. As part of the report, a survey is given to over 10,000 corporate executives. The table to the right summarizes the results from the following question, “How would you compare the corporate ethics (ethical behavior in interactions with public officials, politicians, and other enterprises) of firms in your country with those of other countries in the world?” (highest ranking is most ethical):

World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report

World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report

Transparency International Webpage

Transparency International Webpage

Corruption

According to Transparency International (an international society dedicated to stopping global corruption), corruption is the “misuse of entrusted power for private gain.” Corruption includes bribery, extortion, fraud, collusion, and money laundering.

Bribery is making payment to people in authority as a means of influencing their decisions. The payment may be in cash, but also may consist of a vacation or other gifts.

Extortion is a type of blackmail, where threats are made unless demands are met. The threats may include release of embarrassing information, a refusal to grant permits, or physical harm. Demands are often for payments. Yielding to such threats may make you guilty of bribery.

Fraud is simply deception. It includes concealment of defects or fabricating or falsifying evidence.

Collusion occurs when two parties cooperate to deceive another party. Bid rigging is an example of collusion.

Money laundering is the conversion of money from an illegally-obtained source (e.g. from fraud) into a form that appears to be legitimate.

One of the industries worldwide in which corruption is most common is the construction industry, which is intertwined with engineering practice. A report entitled “Corruption Prevention in the Engineering and Construction Industry” provides reasons why the construction and engineering industry is at high risk for corruption (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009). The reasons include:

- large projects (multi-year and multi-million dollar)

- long supply chains (many companies involved)

- interaction with government officials

- work through third-party intermediaries

- work in expanding markets (developing nations) that do not have appropriate anti-corruption regulatory frameworks and cultures.

Ethical case studies often focus on the gray areas as mentioned previously. But in reality, a significant amount of corrupt activities are carried out by individuals who are well aware that their actions clearly violate every code of ethics as well as some laws. For example, consider this description of a type of corruption known as “price fixing,” from the Anti-Corruption Training Manual (Stansbury and Stansbury, 2008).

“A group of contractors who routinely compete in the same market secretly agree to share the market between them. They will each apparently compete on all major bids, but will in advance secretly agree which of them should win each bid. The contractor who is chosen by the other contractors to win a bid will then notify the other contractors prior to bid submission as to its (the pre-selected contractor's) bid price. The other contractors will then bid at a higher price so as to ensure that the pre-selected contractor wins the bid. The winning contractor would therefore be able to achieve a higher price than if there had been genuine competition for the project. If sufficient projects are awarded, each contractor would have an opportunity to be awarded a project at a higher price. This arrangement is kept confidential from the project owners on respective projects, who believe that the bids are taking place in genuine open competition, and that they are achieving the best available price. The project owners therefore pay more for their projects than they would have done had there been genuine competition.”

Corruption Perception Index

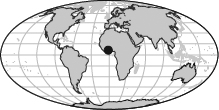

Transparency International publishes an annual Corruption Perception Index (CPI), an index that ranks countries according to the extent to which corruption is perceived to exist among public officials and politicians.

The CPI is based on a scale of 0 to 10; the lower end of the scale indicates a perception of high level corruption, while the high end represents a perception of low level corruption. The CPI results have shown over the years that the incidence of corruption is higher in Africa and in war-ravaged countries. New Zealand is perceived to be the least corrupt while the United States ranks 19th in the 2009 rankings.

Corruption Perception Index

Corruption Perception Index

Unfortunately, in some countries, engineers do not uphold an ethical code. A lack of an ethical code combined with corrupt governments results in widespread corruption. This corruption can take many forms, but as Transparency International points out, regardless of which form it takes, it always results in projects that are unnecessary, unreliable, dangerous, and/or over-priced. This can lead to loss of life, enhance poverty, and negatively affect the economy.

Transparency International estimates that 10 percent of all construction activity worldwide is lost to corruption. Given a worldwide construction activity valued at $5 trillion, the losses add up to a staggering $500 billion annually; this money could potentially fund schools, hospitals, roads, water projects, etc. ASCE has taken a strong stand against corruption, and the ASCE code of ethics Fundamental Canon 6 now reads: “Engineers shall act in such a manner as to uphold and enhance the honor, integrity, and dignity of the engineering profession and shall act with zero-tolerance for bribery, fraud, and corruption” (emphasis added).

ASCE's Combating Corruption in Engineering and Construction Charter

ASCE has created the following “Engineer's Charter.”

We, the undersigned, as leaders in the global engineering community, recognize that corruption of all forms diverts resources from projects intended to raise living standards, threatens sustainable development, impoverishes communities, and tarnishes the reputation of the profession. We hereby join in the battle against bribery, fraud, and corruption in engineering and construction worldwide. We acknowledge, as fundamental principles of professional conduct that engineers as individuals must:

- Ensure that they are not personally involved in any activity that will permit the abuse of power for private gain.

- Recognize that corruption occurs within the public and private sectors, in the procurement and execution of projects, and among employers and employees.

- Refuse to condone or ignore corruption, bribery, or extortion; or payments for favors.

- Urge professional engineering societies and institutions to adopt and publish transparent, enforceable guidelines for ethical professional conduct.

- Enforce anti-corruption guidelines by reporting infractions by any participant in the engineering and construction process.

Further, we pledge to support the formal adoption of these principles by our professional organizations; build professional and public support for zero tolerance for bribery, fraud and corruption; seek transparency in all dealings with public officials and private owners; and coordinate our efforts with the work of Transparency International, the Partnership Against Corruption Initiative of the World Economic Forum, the World Bank, World Federation of Engineering Organizations, FIDIC (International Federation of Consulting Engineers), and other local or global organizations seeking the same goal.

Thankfully, the widespread culture of corruption that exists in many developing countries does not exist in the United States. As Transparency International points out, “People are as corrupt as the system allows them to be. It is where temptation meets permissiveness that corruption takes root on a wide scale.” The “system” in the United States and many other developed countries is such that clear codes of ethical conduct are part of the engineering culture and meaningful penalties exist for unethical behavior (e.g., having one's Professional Engineer's [PE] license revoked or being sentenced to jail time).

This is not to say that corruption does not occur in the United States and other developed nations. New York City, Chicago, and New Orleans are but three of many cities notorious for such activity, often centered around organized crime in construction, trucking, and solid waste management. Note, however, that organized crime's success is often dependent on corrupt local officials and law enforcement personnel.

Corruption also occurs at the corporate level. Price-fixing schemes are often uncovered. In 2005, executives from two construction companies in Wisconsin pleaded guilty to bid-rigging over $100 million in state road contracts. This sent shock waves through the industry in a state that prides itself on its “squeaky clean” reputation. In October of 2009, an investigation began into price-fixing in Montreal, Canada, after a media report that construction costs may be as much as 35 percent higher than competitive “fair market” prices. In September 2009, the Office of Fair Trading in London imposed $200 million (U.S. dollar equivalent) in fines to over 100 construction firms in England that colluded on building contracts. In 2008, the FBI indicted over 60 individuals from the Mafia, construction companies, and labor unions in New York City for extortion in several large construction projects (amongst other charges such as money laundering and illegal gambling). These, and similar acts, serve to lessen the public trust of engineers and the construction industry. It is particularly maddening to discover that elevated prices are paid during periods of economic downturn when limited funding is available.

Public Perception of Corruption in New Orleans

New Orleans has a notoriously corrupt local political and legal system. As a former editor of the major New Orleans newspaper put it, “Corruption in New Orleans had long been a spectator sport, a point of roguish civic pride in a decadent town” (Horne, 2010). But post-Katrina frustration has led to less acceptance of the “old way of doing business.” In 2008–2009 as part of the development of a community Master Plan, residents were asked to rank their top concerns. You might think that given that the city was recently devastated by Hurricane Katrina, that levees and taxes would top the list; yet results shown in the accompanying table revealed that corruption was much more important than levees or taxes (American Planning Association, 2010).

| Concern | Percent of Respondents Ranking as Highest or Second Highest Priority |

| Crime | 54 |

| Education | 30 |

| Corruption in city government | 23 |

| Jobs and economic growth | 21 |

| Affordable housing | 13 |

| Neighborhood development | 13 |

| Levees | 12 |

| Health care | 9 |

| Race relations | 6 |

| Local road conditions | 5 |

| Taxes | 2 |

Corruption and Organized Crime in the United States

The World Economic Forum's biannual Global Competitiveness Report, cited in a previous sidebar, also surveys corporate executives regarding corruption and organized crime. Results suggest that extensive corruption occurs in the United States. For example, for the following question, “In your country, how common is diversion of public funds to companies, individuals, or groups due to corruption?”, the United States ranked 28th. New Zealand was ranked 1st (least corrupt), Venezuela was ranked last, 133rd (most corrupt). For the following question, “Does organized crime (mafia-oriented racketeering, extortion) impose costs on businesses in your country?”, the United States ranked 72nd. Luxembourg was ranked 1st (least influenced by organized crime), and El Salvador was ranked last.

Corruption Humor

Three contractors were visiting a tourist attraction on the same day. One was from Illinois, another from Wisconsin and the third from Minnesota. At the end of the tour, a security guard asked what they did for a living. When they all replied that they were contractors, the guard said, “Hey, we need one of the rear fences redone. Why don't you guys take a look at it and give me a bid?” So they all went to the back fence.

The Minnesota contractor took out his tape measure and pencil, did some calculations and said, “Well I figure the job will run about $900: $400 for materials, $400 for my crew, and $100 profit for me.”

Then the Wisconsin contractor took out his tape measure and pencil, did some quick figuring and said, “Looks like I can do this job for $700: $300 for materials, $300 for my crew, and $100 profit for me.”

Without so much as moving, the Illinois contractor said, “$2,700.” The guard, incredulous, looked at him and said, “You didn't even measure like the other guys! How did you come up with such a high figure?”

“Easy,” he said. “$1,000 for me, $1,000 for you, and we hire the guy from Wisconsin.”

(This joke has circulated for years, with different states substituted depending on the joke teller.)

Personal Experience with Corruption in Ghana

Dr. Sam Owusu-Ababio, a professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, returns often to his native Ghana. The following are his observations on what he has learned of corruption in the transportation sector in Ghana.

Unlike the other sectors of development, the transportation sector always has large capital expenditures involved, and as a result, it is more susceptible to corrupt practices. It is easier to manipulate or hide some transactions given the absence of information and communication technology that could otherwise be used to improve outdated financial and project monitoring or auditing processes. Electronic databases or integrated database systems that can facilitate record keeping and the monitoring process are lacking. This makes it difficult to find the trail of specific fraudulent transactions, especially in agencies where poor practices exist in keeping records.

Whenever there is a change in government, there is always a massive overhaul of the transportation sector. High-level responsibilities and appointments that deal with planning and funding of transportation infrastructure are sometimes allocated to people with no expertise in transportation planning or administration. Consequently, policy decision-making processes lack the depth of any rigorous planning process that encourages community-wide involvement and seeks to address long-term travel demand forecasting needs, environmental, economical, and social impacts. The political appointments are also perceived to come with a hidden agenda in the form of selecting people who can make decisions that provide more opportunities for funds diversion for personal gain. Eventually, substantial amount of public resources are sunk into projects that fail to adequately address the immediate and long-term transportation needs.

Some specific observations of corruption follow.

- Workplace recruitment, transfers, assignments, and promotions are often based on favors and connections with people in power rather than merit. One can get promoted by being cooperative with corruption practices within an agency. This approach leads to more opportunities for corruption to surface and blossom.

- There is a lack of supervision and adequate record keeping when it comes to usage of public assets. It is not uncommon to have public assets such as construction equipment or vehicles put to use on a private job to benefit the engineer who oversees the equipment. Vehicles assigned to public officials for public work are frequently used outside the prescribed hours of use. Where materials and parts are not well inventoried, some get stolen by agency employees and sold on the market.

- During the feasibility and design phases of a project, consultants can overdesign or purposefully expand project feasibility components if the fee for consultancy services is tied to some percentage of the overall cost.

- When it comes to contracts allocation, a contractor's expertise may not count; rather, it is the connection with the decision-makers or political figures and ability to pay a bribe that can often determine one's success in securing a contract. The contractor with the connections may receive inside information about the bidding process to help tip the decision in his/her favor. In some cases the contractor may be advised to deliberately lower the bid price to win the contract and then after the contract is won, change orders can be submitted to make up for the bid deficiency. In return, the provider of the inside information can get a bribe, which is often negotiated in terms of a percentage of the contract sum. The negotiation process can create a delay in the awards of the contract and the ultimate start of the project.

- Some contractors may choose to lie about their qualification requirements in order to secure a contract. They borrow construction equipment while attempting to conceal the identity of the owner. They can make financial arrangements with corrupt bankers to provide them with financial documentation to demonstrate their financial capacity, all done to create an illusion of their ability to compete in the bidding process. Occasionally, some contractors after collecting mobilization funds can abandon the project.

- Some contractors may conspire with corrupt engineers to falsify quantities in change orders during project construction. In addition, work certification for compliance may also be compromised to aid the contractor in return for a bribe.

- Processing of claims for payment of completed project work is one of the stages where bribing is practically inevitable. The process is cumbersome and slow; it is set up to require multiple approvals. If one wants to accelerate the process, then some negotiations in the form of bribes will take place along the approval paths to avoid significant delay in payment.

- Road infrastructure maintenance requires periodic assessment of conditions to help identify maintenance needs and prepare corresponding budgets. The field conditions data are sometimes not collected due to unavailability of tools for conducting the survey and lack of trained personnel. However, the corrupt engineers are able to prepare the budget either based on a specified percent increase of previous budgets or use fictitious condition data.

As a result, corruption steals resources from the transportation system and directly or indirectly affects the quality of the system components. The main impacts as observed in Ghana are as follows:

- Roads are built to less desirable standards and tend to deteriorate rapidly (Figure 17.1).

- There is overcrowding of public transportation systems since the road system is poor.

- There is increased potential for more accidents because of inadequate resources to manage incidents when they happen; this can further create congestion.

- There is constant flooding and washing away of roads and bridges (Figure 17.2).

- Maintenance of deteriorated systems components is deferred, requiring more money to fix them at a future date.

Figure 17.1 Deteriorated Roadway in Ghana.

Source: Courtesy of S. Owusu-Ababio.

Figure 17.2 Impassable Roadway in Ghana.

Source: Courtesy of S. Owusu-Ababio.

Outro

It is important to keep in mind that you are always accountable for your decisions, and that your decisions often affect others. Unethical engineering decisions may not only negatively affect you and your career, but also your coworkers, your employer, your client, and the general public.

chapter Seventeen Homework Problems

- 17.1 Print out a copy of the NSPE Code of Ethics Examination (available at www.wiley.com/college/penn) and take the test without looking at the answers before completing the exam. Self-grade the exam after you have taken it and hand in the graded copy to your instructor.

- 17.2 For each of the quiz questions from Homework Problem 17.1, state the pertinent section of the NSPE code of ethics that addresses each question.

- 17.3 Why do some students cheat? List five reasons/excuses.

- 17.4 How do students justify cheating? List five ways.

- 17.5 Which portion(s) of the ASCE code of ethics would you violate by looking at the answers prior to taking the online ethics exam in Homework Problem 17.1 and not reporting that you did so?

- 17.6 The NSPE's Board of Ethical Review (available at www.wiley.com/college/penn) contains hundreds of case studies. For one of these case studies selected by your instructor, answer the following questions.

- For the ethical question(s) stated in the case study, what are two possible unethical responses. For each response, provide justifications and counter these justifications with specific text from the ASCE Code of Ethics.

- Do you agree with the conclusion reached by the Board of Ethical Review? Why or why not?

- 17.7 The ASCE defines sustainability as “the challenge of meeting human needs for natural resources, industrial products, energy, food, transportation, shelter, and effective waste management while conserving and protecting environmental quality and the natural resource base essential for future development.” This definition is provided in the ASCE Code of Ethics. Do you think that an engineer that does not practice in a sustainable manner is unethical?

- 17.8 Cite specific violations of the ASCE Code of Ethics reported in the “Personal Experience with Corruption in Ghana” section of this chapter.

- 17.9 Are the reported practices in Ghana unethical if no professional code of ethics exists in that country?

- 17.10 Other than adopting a code of ethics, what can be done to change engineering practice in Ghana to make it more compliant with a code of ethics such as that of ASCE?

Key Terms

- bribery

- code of ethics

- collusion

- corruption

- extortion

- fraud

- money laundering

- whistle-blower

References

American Planning Association. 2010. “By the Numbers.” Planning: 76(1), 37.

Carpenter, D. D., T. S. Harding, C. J. Finelli, S. M. Montgomery, and H.J. Passow. 2006. “Engineering Students' Perceptions of and Attitudes Towards Cheating.” Journal of Engineering Education, 95(3): 181–194.

Horne, J. 2010. “Trump Card.” Planning, 76(1), 35–36.

Martin, M. and R. Schinzinger. 2004. Ethics in Engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill.

PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2009. Corruption Prevention in the Engineering & Construction Industry. http://www.pwc.com/en_GX/gx/engineering-construction/fraud-economic-crime/pdf/corruption-prevention.pdf, accessed August 29, 2011.

Stansbury, C. and N. Stansbury, 2008. Anti-Corruption Training Manual. Global Infrastructure Anti-Corruption Center/Transparency International (UK). http://www.giaccentre.org/documents/GIACC.TRAININGMANUAL.INT.pdf, accessed August 29, 2011.