10

THE ROAD MORE TRAVELED

Like boring, predictable paths? The sure and steady way could be yours.

The least sensational, but most reliable, road to riches is saving linked to good investment returns. This is very American—the Calvinist catechism, rooted in Judeo-Christian values of virtue. Frugality and industriousness do pay. This road is wide enough for anyone with a paycheck. It has spawned thousands of how-to books over the decades, ranging from Suze Orman to The Millionaire Next Door.

The first step is saving. Fact: Some folks just can’t—regardless of income. Some make half a million a year and blow it all. Some are naturally frugal. Some folks can improve. Others never will. But saving is a must here.

Step two is getting OK, but not phenomenal, investment returns. The magical power of compound interest assures even the lowliest part-time garbage collector can do this if he or she saves a few thousand a year. Forbes list? No. But anyone can be a multimillionaire.

Note: A million isn’t much anymore! A million invested well kicks off about $40,000 a year in cash flow (see why later)—not enough to feel rich. But it isn’t a stretch to hit maybe $10 million-plus with an OK job and discipline. This road isn’t sexy. Frugal isn’t known for sexy! But the good news: This road doesn’t require degrees—or even high school (but education helps with better- paying jobs). This is the exact reverse of the road less traveled. It is the road more commonly traveled to riches.

INCOME MATTERS

Earn more to save more—easy as that. Garbage collectors can’t save as much as a doctor may. That doesn’t mean doctors save more—they’re notoriously bad savers—but the possibility is there. Find a job in a well-paying, relevant field you like. If you’re in a sinking industry, get a different job. If you live in a low-paying geography, move. Where? Preferably to Texas, Florida, or Washington! All have no state income taxes and in 10 years will have more better-paying jobs than high tax states. (Read more about why some states are just better, and others worse, in Chapter 9.)

In any career, consider the cost/benefit payoff. How long must you go to school and intern? Is it worth it? Review Chapters 1 and 7 on sectors likely to become or remain relevant. Some may bristle and say, “But you should do what you love!” Yes, but like Marilyn Monroe would say—my goodness, doesn’t it help if what you love pays a lot, too? If your passion is truly social work, teaching kindergarten, or quilting—fine. Then focus on frugality. It can be done! I have clients who were postal carriers, teachers, cops, and so on. They did it. Frugal!

The Job Hunt

Whether starting your career or farther along, read What Color Is Your Parachute?, the classic by Richard Nelson Bolles. First published in 1970, this annual publication helps determine what exactly you want/need from a career. Maybe you find you don’t want riches at all! You may land a high-paying job, but if you’re miserable, you won’t stick with it.

OK! You know what you want to do—now find a firm paying better than its peers. Ignore job-hunting online blogs and chat rooms. They’re patrolled by job hunters knowing nothing about the firm and disgruntled current and former employees with motivation to mislead. I know a guy whose son told me he gets all his job-seeking tips from chat rooms. I haven’t figured a graceful way yet to tell the father his son is an idiot.

Instead, think like a private equity manager. Pick up the Wall Street Journal and read about your target industry. Find folks you know in the industry. Interview them. They’ll have insight and likely help with interview material—and have the skinny on who pays what. An added benefit: When you ask people for advice, you appeal to their ego. Now, they’re invested and want to help. If they help you land a job, that’s great for you and an ego boost for them!

Making the Pitch

A job hunt is just a sales pitch—you’re the product. You must sell on every road! The better you sell, the faster you get a bigger paycheck. Get Guerrilla Marketing for Job Hunters 3.0 by Jay Conrad Levinson and David Perry. Ignore its nonsense about “outsourcing” being a problem. Overall, it’s a good job-hunter’s book. Also, The Job Search Solution by Tony Beshara has unique and helpful insights.

Post your resume on Monster, Indeed, LinkedIn—all those places. But that’s not enough. You must sell. Network. Call firms that aren’t hiring and request an informational interview. Have lunch with friends of friends and friends of friends of friends. Ask what they do. Find it fascinating. Ask them for help. Don’t forget, you need a good, professional resume, so read The Elements of Resume Style by Scott Bennett.

Before you interview, practice with a friend. Don’t volunteer personal information. Talking personal stuff is (1) creepy and (2) turns off your interviewer. To ace an interview, leave your personal stuff at home.

Once you get the job, you’re not done. Keep selling yourself. See yourself as a ride-along or potential CEO (read those chapters for tips on being a well-compensated standout). You may need to choose—will you go deep as a specialist, or broad as a manager? Both can pay well, but in your field one may pay better. Never stop researching and selling yourself. Maybe you don’t want to work this hard—your choice, but the more you earn, the more you can save. And the more you save, the more your money works for you and the richer you get on this road.

SAVING GRACE

How much should you save, realistically? Pick a retirement age, then calculate what you need. A financial calculator or Excel helps. (If you’re afraid of either, ask a teenager’s help.) Figure how much you want by date X. Is $2 million enough? $10 million? (Much above that and you need a really high-paying job or another road.) Will you need more or less income (inflation-adjusted) than you need now? Will your kids be done with school and life be cheaper? Can you skip the vacation home to save more? Or travel? What about other income sources? Some advisers suggest you assume 70 percent of your income postretirement. No! It’s all personal—some need more, some less. Pick a number in today’s dollars—be a touch generous to be safe. Then, adjust for inflation for date X.

But how? Easy, even if the following formulas look scary. Basically, you assume an inflation rate. Then, pick a time in the future—say, 30 years. Then, calculate how much inflation increases the value of money today (i.e., compounding interest). To do it, use this formula:

![]()

For those who’ve forgotten their statistics, FV is the future value—how much a dollar today will be worth later after compounding interest does its trick. PV is present value—money today. R is the interest rate—what we’re using for inflation. n is the number of years between now and then.

To live on $100,000 in today’s dollars, figure how much that is in 30 years with inflation averaging 3 percent. Multiply $100,000 by 1 plus 3 percent, raised to the power of 30. Use Excel (it has an FV shortcut) or a calculator:

![]()

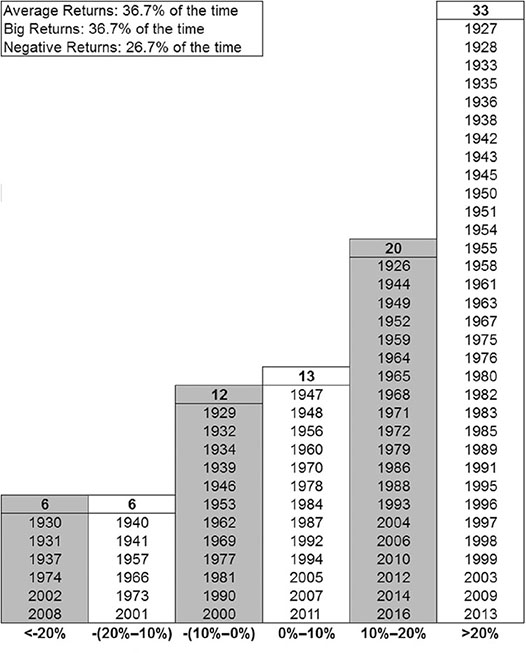

Figure 10.1 Average Returns Aren’t Normal .

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., and FactSet; S&P 500 Total Return, 12/31/1926–12/31/2016. May not sum to 100% due to rounding

You need about $243,000 (more if you assume higher inflation). But how much must you save to get there? That’s easier. For your portfolio to last as long as you do, you generally shouldn’t take more than 4 percent in cash flow each year. So divide $243,000 by 4 percent to get $6,075,000. So go save $6 million.

Saving $6 Million???

Seems too much. How can you save so much? That would be salting away $200,000 annually for 30 years. Few folks can do that. So you save less and invest en route. Over time, through the magic of compounding interest, you get to $6 million. So how much to really save each year?

![]()

PMT is your payment—how much you must save each year. This is the number we’re trying to figure out. The interest rate is i—your assumption of what rate of return you will get. The number of years between now and when you want to start taking money is n. And, again, FV is your desired future value—in this case $6 million. (If this terrifies you, Excel has a function you can use—just remember future value—or you can ask your teenager for help.)

For this exercise, assume i is 10 percent (about what I expect the long-term stock market average to be). FV is $6 million, and you retire in 30 years (n):

![]()

So for $6 million, save $36,000 a year for 30 years—$3,000 a month. Still seems like a lot? That’s why a high-paying job helps. But it’s not hard to get to $36,000:

- Contribute the 2017 401(k) maximum—$18,000 (plus, that cuts your tax liability!).

- If your employer matches 50 percent as my firm does, that’s another $9,000 (free!).

- Contribute the 2017 IRA maximum—$5,500.

That’s already $32,500. Now save another $3,500 a year—$292 a month—in a taxable account. Easy! If married, get your spouse to save via a 401(k) and/or IRA. Maybe you can save every dime tax deferred!

Maybe saving $36,000 per year is out of reach now. Should you give up? No! Use Excel and make assumptions about how you can increase savings each year, assume a rate of return, and tinker until you hit your end value. Stick to the plan. Remember the time value of money—earlier saving is simply worth more. Save as much as you can as early as possible and you’ll have an easier time later. Can’t say it any simpler!

What difference do a few years make? Tons. A 25-year-old saving $6 million by age 60 need only save $22,000 a year (assuming 10 percent returns). Max your 401(k) with a partial employer match, max your IRA, and you’re done. But start at 40 and you must save $105,000 a year, or not retire at 60, or give up your $6 million dream. Your call.

The 3 percent inflation and 10 percent returns are just assumptions. Play with those a bit. For example, maybe you’re a pessimist who thinks the stock market will only average 6 percent over the next 30 years. Then you must save more. I’m not saying saving $36,000 a year is easy. I’m saying know how much you need and create a plan to achieve it. Then stick to it.

How the Heck Should I Save?

A high-paying job helps. Being frugal helps, too. There are plenty of books preaching how to be frugal—I don’t even need to name them. They’re all variations on the same theme: Skip mocha-caramel-triple-lattes. Pay off credit card debt. Avoid designer labels. Shop at discount stores, thrift shops, or eBay. Buy used cars. Eat in more, out less. Total no-brainers. Some can’t do this—just can’t. If you can, great! If you can’t, reprogram yourself (very difficult) or get a better-paying job.

Here’s an eye-opener if you don’t think you can save that much. Figure what you’re saving and see where you’ll be after 30 years. Suppose last year you saved $2,000. Solving for future value (you’re a pro at these by now):

![]()

You promise yourself you’ll save more next year. Will you? Use the previous assumptions for i and n. Your PMT (amount saved each year) is $2,000:

![]()

Saving $2,000 gets you to $329,000—kicking off about $13,000 a year in 30 years (about $6,150 in 2015 dollars). That’s no road to riches.

GET A GOOD RATE OF RETURN (BUY STOCKS)

We keep using 10 percent as our assumed return. Fact is, few folks do that well. Most professionals don’t, even though it’s not hard.

How can you? Easy—invest in stocks, pretty much all the time. Diversify globally, using something like the MSCI World Index or ACWI Index as your guide (www.msci.com). While you must be sure of your goals, time horizon and cash flow needs, I am a huge fan of stocks because they have superior long-term returns. An all-equity approach is wrong for people with short time horizons. But that’s not you on this road, presuming you aren’t saving to buy a house in the next five years (for the roof over your head, not an investment). This chapter, by definition, means you have a long growth goal and need stocks. Almost always.

There may be times when, to sidestep an upcoming prolonged market downturn, you step into cash and bonds—that can help put serious spread against stocks. If your benchmark is the global MSCI World Index, and it’s down 20 percent one year, but you’re down just 5 percent, you’ve beat stocks by 15 percent—that’s awesome. But true bear markets are more rare than the media wants you to think and if you really know how to time them you should go into OPM instead (see Chapter 7).

Most folks have a far longer time horizon than they think (we’ll get to that in a bit), and if you weren’t interested in growth, you wouldn’t be reading a book about getting rich.

Life Expectancy Tango

Does being all in stocks scare you? It’s less risky than most people think because they envision their time horizon all wrong. People think, “I’m 50. I want to retire at 60. That’s 10 years, so I’ve got a 10-year time horizon and should invest that way.” Very wrong! Unless you want to run out of money, your time horizon is as long as you need your assets to last—usually your life or your spouse’s (at least as long as both of you)—longer if you leave money to kids.

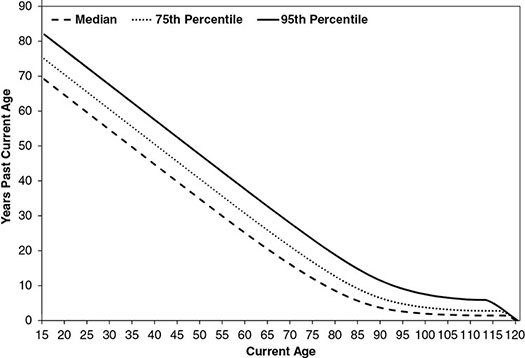

Even those who get that right usually err—they underestimate how long they’ll live. Figure 10.2 shows median life expectancy as well as 75th and 95th percentile expectancies from IRS mortality tables. The x-axis shows current age. The y-axis shows years past current age. The dashed line is median life expectancy—85 for a 65-year-old.

Figure 10.2 Life Expectancy .

Source: IRS Revenue Ruling 2015-53 Mortality Table

The average 65-year-old will live another 20 years—if you’re average. Half live longer. If you’re healthy and from a long-lived family, you may live much longer! Plus, you should assume on the long-lived side so you won’t hit age 85 and run out of money. A healthy 65-year-old should plan on at least a 35-year time horizon. And life expectancy keeps rising. If you’re young now, by the time you hit 65, median life expectancy will be much longer.

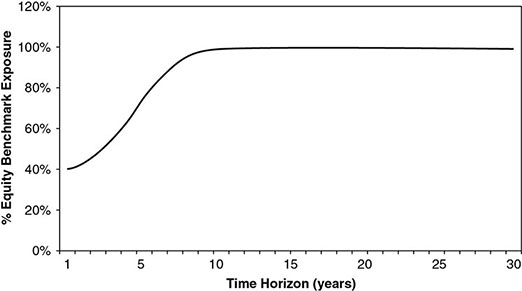

So? Longer means holding more stocks longer. Figure 10.3 shows how to think about equity exposure based on your time horizon. For time horizons greater than 15 years (like you), you want all-equity if this is your road to riches.

Figure 10.3 Benchmark and Time Horizon

Goal Confusion

Another factor where investors err is determining goals. Most can’t articulate their goals in a few short words. We think we’re unique (we are—just like everybody else) and our goals must be, too. No. The finance industry likes to confuse with complicated surveys and questionnaires—from which they can justify expensive services. There are only three prime investing goals:

- Growth. You need your money to grow as much as possible to cover living expenses later, or stretch now to cover current cash flow needs. Or maybe you just want to leave a bundle to kids, grandkids, or albino snow leopards, or whatever you’re into.

- Income. You need cash flow now or soon to cover living expenses, and you don’t really care about growth so long as you get your cash flow.

- Growth and income. Some combination of the first two.

One of these goals fits 99.993 percent of you. I didn’t include capital preservation. It sounds nice! But it means you take no risk and get no growth—not helpful on this road. A true capital preservation strategy means losing money at inflation’s pace. Capital preservation and growth is a finance industry fairy tale. Calorie-free cake. Not possible. Ever! For growth, you take risk, and capital preservation is total absence of risk. Someone selling you this strategy is conning you, whether he knows it or not. If you’re on this road, the more equities you can stomach, the better.

THE RIGHT STRATEGY

So, you know you need stocks, preferably global, like the MSCI World. Now what? Invest like your benchmark, most of the time. Sounds simple, right? But I can’t tell you how often I hear, “Yes, I need an equity benchmark, but stocks scare me right now. I’ll be safer for a while with bonds and cash.” People see being safe as having big allocations to cash or bonds. Bonds reduce volatility. That’s safe—right?

Wrong! Cash and bonds when you need an all-equity benchmark is about as risky as can be! You are seriously deviating from your plan—increasing the odds you’ll miss your goal, maybe by a lot. That’s not safe, that’s dangerous. If your benchmark is up 30 percent one year, but holding bonds you’re up only 6 percent, you may be comfy but you lagged by 24 percent. You’re behind now—huge. You need to beat the market by an average of 1 percent every year—tough to do—for the next 24 years to make up for that.

Go Global

Why the global emphasis? Isn’t the S&P 500 enough? US stocks are only about 41 percent of the overall world if you include emerging markets (and you generally should).1 By not investing globally, you miss opportunities—and a chance to reduce volatility. Why? The broader your index, the smoother the ride.

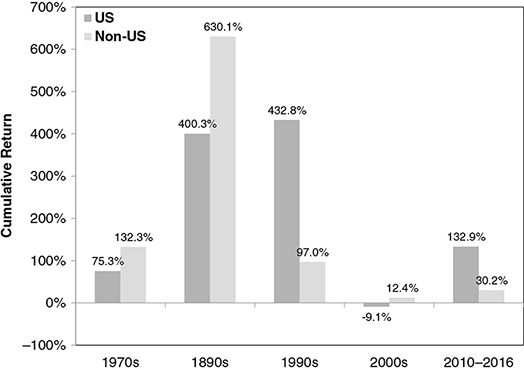

Think of the super narrow and very volatile NASDAQ—it had a steep ride up in the late 1990s and a steep ride down after. It only just broke even. World stocks, meanwhile, are up 78.9 percent since the tech bubble’s peak.2 Broader indexes are smoother, and nothing’s broader than global. Plus, US and foreign stocks trade leadership, as shown in Figure 10.4—one leads the other for years, by a bunch. You just don’t know which will lead next. So own both by going global. If you do know which will be best; again, be an OPMer.

Figure 10.4 Domestic and Foreign Leadership Trades Off .

Source: FactSet, as of 1/12/2017. S&P 500 Total Return Index and MSCI EAFE with net dividends from 12/31/1969 to 12/31/2016

Passive or Active?

Now what? How much time do you want to spend on investing instead of focusing on your job to earn as much as you can so you save and then invest? If a lot, I’d say, “Really?” If you’re on this road to get rich, you probably don’t have the spare time to become expert at a very difficult activity where most folks fail. If you’re determined, then read my 2007 New York Times best seller, The Only Three Questions That Count. It covers the turf.

Avoid anything suggesting a “magic formula” or “all you need is these types of stocks and not those.” Most investing books lead you astray because they’re largely based on faulty assumptions that one size, style, or type of stock is best forever. Untrue! (I give heavy detail why in my aforementioned book, too.) Fact is, the only way to beat the market in the long term is knowing something others don’t, repeatedly. And that is very hard to accomplish. Just a warning.

If time for you is scarce, as it should be on this road, what you do depends on how much money you have and whether you want to be passive or active. (Passive means getting market-like returns investing just like the market, active means trying to beat the market by varying from it somehow.) With less than $200,000, just be passive.

Many try to be active, but odds are 4-to-1 or more you lag markets—huge. Most who try, fail. With under $200,000 you’d mostly use mutual funds. Many people do, but they’re costly and tax inefficient. You can actually have a loss and receive a tax bill for gains—very perverse tax-wise. You own the fund but get taxed on realized gains inside the fund. Only in America! Overseas, they don’t do this.

Next, most funds lag the market. And there’s no way to know which will and won’t, so the odds are stacked heavily against you. Diversify into a handful of active mutual funds and you are almost guaranteed to lag a passive strategy.

Doing Passive Right

You can do passive easily! As I write, the whole world market is about 41 percent US, 47 percent developed foreign, and 12 percent emerging markets.3 Open a brokerage account somewhere cheap—I don’t care where. A discount online broker is fine. Now, buy index funds or exchange traded funds (ETFs—pure passive slices of the market but taxed like a stock instead of a fund) to match the weights of the world. Buy about 41 percent of a cheap S&P 500 index fund or ETF; 47 percent Europe, Australasia, and Far East (EAFE); and 12 percent Emerging Markets. Buy more in the same percentages as you save. Then leave it alone. The idea is, like Chapter 8’s Ron Popeil would say, “Set it and forget it.” Hands off, for decades.

Make sure your funds have low expenses. For the S&P 500, you could buy the “Spider” ETF (stock symbol, SPY), an iShares ETF (IVV), or Vanguard’s index fund (VFINX). Whatever you choose, make sure you buy a cheap, plain, vanilla ETF or index fund. Some fund families label pricier strategies as “index” funds. Don’t be fooled. Be frugal. For EAFE, consider the iShares ETF (EFA), Vanguard’s ETF (VEA), or their VDMIX. For Emerging Markets, you could buy the iShares ETF (EEM) or Vanguard’s ETF (VWO). Your broker may have differing additional fees for these, or not. There’s scant difference between ETFs and index funds except maybe 30 basis points of costs—pick the cheaper one.

I can’t stress the importance of picking boring, vanilla index funds or ETFs enough. The more popular passive funds get, the more active strategies try to masquerade as passive. It’s all branding. Some shops create new niche “indexes,” then launch a fund to mirror them. Presto, an index fund! There are newfangled indexes for companies surpassing a minimum book value, companies that invest a certain percentage of free cash flow back into the business, companies run by women, and other niche—often arbitrary—criteria. Some of the indexes are even actively managed. No disrespect to any of these strategies, but they aren’t passive. They’re active, presuming one type of company is superior for all time. But everything has its day in the sun and the rain. My advice: Forget the gimmicks, and remember, boring is best in the long run.

Help or DIY?

Have much over $200,000? (Good for you! You’re making the world a better place.) Now you belong in individual stocks. It’s cheaper and more tax efficient—hands down. Folks rarely notice, but lump in expense ratios, broker fees, and so on, and you can give away 2.5 to 3.5 percent or more on mutual funds.

If you’re in the $200,000 to $500,000 range, you’ll do less harm and be more efficient with an ETF strategy. (Remember, ETFs track indexes but act and trade like single stocks.) Under $500,000 you really can’t diversify enough with individual stocks; but above $200,000, you can begin making country and sector decisions via ETFs that, done right, can add to your bottom line. And if you have over $500,000, you absolutely belong in individual stocks. No mutual funds! Too expensive for you.

But that question again: Passive or active? Passive beats most who try to manage money actively. To be passive, you want to own stocks best representing the world. To do this, you can go to http://www.ft.com/ft500 and download the Financial Times 500—this is a list of the world’s 500 largest stocks by market cap, updated regularly. You needn’t own all 500—that would be very pricey—but you could buy the largest 100 or so and get good global coverage. To round out your portfolio, you could buy some percentage in a small-cap global ETF (like State Street’s International Small Cap ETF—ticker GWX)—the cheapest way to go. That’s passive. As you save more, keep buying in the same percentages. Otherwise, leave everything alone.

Whether you have a smaller asset pool in ETFs or have graduated to individual stocks, to be active and try to beat the market, you must hire a money manager. This isn’t easy, either. You must ask the right questions. You don’t want anyone who suggests he “manages” a portfolio of mutual funds or “selects” a stable of discretionary money managers. All you’re doing is layering cost on more cost, eating into return. Don’t hire an intermediary—hire a decision maker who knows what he/she is doing. Few do. On the following pages I list questions to ask the potential caretaker of your assets. Memorize them. Type them up. Take them with you.

Stick with Your Stocks, Unless . . .

Stocks sometimes fall a lot, but most years they’re up. For almost the entire bull market that started in 2003, folks griped about how terrible stocks were and how bad they would do. Yet stocks rose each year: 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, and 2007. We’ve seen similar during the bull market that began in 2009, shaping up to be history’s least loved. Take most five-year periods and they’ll be up, too. The 1990s bull market ran nearly the entire decade, as did the 1980s. The 2009 bull is eight years young. During all that time, you belonged in stocks. And you will in the future.

Believe me, staying in stocks is harder than it sounds. You will absolutely be tempted to bail when the market gets bumpy. Don’t do it unless you’re really, really, really darn sure stocks will fall a lot for a significant period. Don’t do it after they’ve fallen a lot. Ask yourself, what do you know about market timing that everyone else doesn’t? My guess is, nothing. Again, if you do you should start an OPM firm (see Chapter 7).

How can you know if it’s a bear market? It’s tough. It’s certainly not when everyone expects one. Professionals are terrible at forecasting bear markets. The media is worse. So if folks are commonly predicting bad times, know you should own stocks. Again, to become a bear scholar, go read my 2007 book, The Only Three Questions That Count. If you won’t do at least that much individual study, you shouldn’t try to make these decisions yourself.

Bearing with Bears

Even if you suffer a bear market fully invested, it’s OK. Stocks’ long-term superior averages include bear markets. You needn’t miss every bear market. True passive investors rigidly remain invested in good times and bad, no matter what! And they overwhelmingly beat those who try to time markets. To time markets, you really must know what you’re doing, and precious few do. That’s really hard.

One warning: Corrections are different from bear markets. They are short, sharp shocks—big, sudden drops designed to scare the pants off you. They can happen once or twice a year. Don’t be fooled. Remain invested and it will be over in a few months. Real bear markets start slow and calm. People are optimistic after the peak. Anyone pessimistic then is seen as nuts. Stocks drop a little month-to-month, but nothing dramatic. Meanwhile, fundamentals unravel and few notice. Bear markets don’t start violently—not even in 1929—if measured correctly. (See my 1987 book, revised in 2007, The Wall Street Waltz, on this.)

BONDS ARE RISKIER THAN STOCKS—SERIOUSLY

But wait! Can’t stocks be down huge? Isn’t it better to give up some return for a sleep-at-night factor? No. Remember, this is The Ten Roads to Riches, not The Nine Roads to Riches and One Road to a Comfy Night’s Sleep. In the long term, stocks aren’t risky. In the short term, they’re volatile, which scares people. Ignore the caveman in you wanting to hide from scary things. Investors fail with long-term returns because they can’t get this in their bones: The near term doesn’t matter—hardly at all! The roads to riches are long. The following box shows the stock-versus-bond decision over 20 years. It’s a no-brainer. Since 1926, there have been 72 twenty-year rolling periods. In 70, stocks beat bonds—848 percent to 246 percent! The first period bonds beat stocks, January 1, 1929, through December 31, 1948, saw the Great Depression and World War II. But bonds barely beat stocks—1.4 to 1. The second, January 1, 1989, through December 31, 2008, saw the tech bubble burst and the global financial crisis. Then, too, bonds just barely won—1.1 to 1. And both times, stocks were still up overall. So it isn’t worth the risk with bonds at all, long-term.

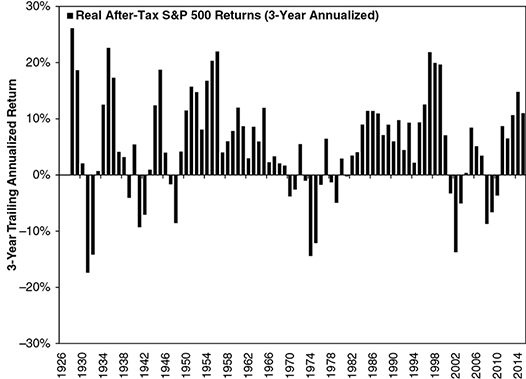

Still unconvinced stocks are better? Most folks think bonds are safer. They are, if you just consider volatility risk over short periods. Fact: Given just a bit of time, stocks not only have far better returns, but more consistent ones. Figure 10.5 shows three-year trailing returns, adjusted for inflation and taxes, for bonds. Compare that with stock returns in Figure 10.6.

Figure 10.5 Real After-Tax US 10-Year Treasury Returns, 1926–2016

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., and FactSet, as of 1/31/2017

Figure 10.6 Real After-Tax S&P 500 Returns, 1926–2016

Source: Global Financial Data, Inc., and FactSet, as of 1/31/2017

Given a bit of time, stocks have fewer negative periods than bonds. Even supposedly safe US Treasuries have periods of multiple, consecutive negative returns. And three-year returns over 10 percent are rare. Yes, stocks’ negative periods are bigger, but they’re blown away by the bigger, more consistently positive periods. If you have a longer time horizon (you do), stocks are less risky.

Maybe you’re one of the many who believe “everything’s different now” and the world’s worse, and capitalism is horrible, and stocks are done. Forever! That was a fringe view when this book first came out, but post-crisis, it’s everywhere. No system is perfect, but capitalism took us from subsistence farming to high-tech space-age prosperity. It still works. Moore’s law hasn’t run out yet. Your smartphone does more than the world’s most powerful computers did in the 1980s. Drones have started delivering pizza in Australia. With new technology come boundless opportunities for creative users to spinnovate tech into some product or service you can’t live without. All fuel for future earnings—and stocks.

There are some people who, no matter what, won’t ever hold 100 percent stocks. If this is you, that’s fine! Just remember, when calculating for how much to save each year, use a lower return expectation. It will be tougher and slower to get rich on this road if you don’t use the magical power of stocks’ superior compounding returns. It can be done, though it takes longer. From our earlier example, to get $6 million over 30 years with less stocks, maybe you assume an average 7 percent return. That means saving $63,500 a year with a better-paying job. If you can, great! If not, maybe retire later, start saving earlier (you get to $6 million at 7 percent in 40 years saving only $30,000 a year). Or maybe die sooner. It’s up to you.

Stocks, Stocks, and More Stocks . . .

I spend no time telling you how to pick winning stocks because, first, no one can teach you to do that in one chapter. For that, go to my first and fourth books (Super Stocks and The Only Three Questions That Count). Next, the decision whether to hold stocks, bonds, or cash, and in what percentage, determines most of your portfolio return. Stock-picking, done right, still doesn’t add that much to your returns. My firm does that for a living. Trust me.

LIKE HETTY?

On this most common road there are few famous folks to learn from. One famous character and one of my favorites was too frugal—Hetty Green. Hetty didn’t much do stocks. She rarely sought big returns—aiming for 6 percent (before income taxes existed) via mostly bonds. She bought stocks only at the height of panic when stocks were cheap. She had ice water for blood—she was sanguine during market crises that made somber men sob in fear.

In 1916, she died with about $100 million.4 She saved every penny. Hetty didn’t need higher returns. She was neurotically frugal. She didn’t spend on clothes—she wore the same black dress endlessly. She sewed securities (before online trading!) into her dress and shawl for safekeeping—they kept her warmer. She had her son resell her newspapers. She lived in a cold-water, unheated apartment. She could afford anything but ate mostly oatmeal and graham crackers. When her young son injured his leg sledding, she wouldn’t pay for a doctor. She stood in line for a free clinic and used a homemade poultice. It didn’t work. Her son’s father (whom she ditched—he wasn’t good with money) stepped in to pay to have the gangrenous leg amputated. She wouldn’t.

For a woman to build a portfolio over $100 million in those days wasn’t rare—it was unheard of. Her financial prowess and shabby attire earned her the nickname “the Witch of Wall Street.”

So no, you don’t need stocks’ superior returns on this road. But I bet you won’t let your kid’s leg get so bad it needs to be amputated. You can do it like Hetty, or you can ignore your fears and handle more stocks. Or you calculate what you’ll need to save given a lower return expectation.

READING FOR DOLLARS

There are thousands of books on saving and investing. Most aren’t so good—it’s the same advice over and over again. If the advice worked in the first place, you wouldn’t need the same old advice regurgitated countless times—just the one book would suffice. But don’t be discouraged. You can read the ones I recommended earlier, or one of these.

- The Ultimate Gift by Jim Stovall. I gave a copy to each of my sons—a story with a key message—not only how to think about money, but how to be a better human being.

- The Millionaire Next Door by Thomas J. Stanley and William D. Danko. This one won’t tell you how to save or invest, but it was pretty eye-opening for a lot of folks when it first came out. It’s true: Most millionaires are Average Joes.

- If you can’t tell a stock from a bond from cattle futures, read Investing for Dummies by Eric Tyson. Here you’ll learn how to open an account, navigate a broker, and start buying stocks.

- The Only Three Questions That Count: Investing by Knowing What Others Don’t by yours truly. Fact: Most investing books are bad for your health. They tell you to “only buy these stocks, not those” or imply there’s some magic equation. Nonsense. You can’t beat the market by doing some trick a million other people can read about. To beat the market, you must know something others don’t. Tough to do! My book shows you how to figure out what most others don’t know using just your noggin and some statistics. For that matter, try any of my other stock market books: Super Stocks, The Wall Street Waltz, Beat the Crowd, or 100 Minds That Made the Market (with a Hetty Green biography).