Chapter 8

Why We Buy the Things We Buy

In This Chapter

![]() Summarizing how nonconscious processes impact consumer decision making

Summarizing how nonconscious processes impact consumer decision making

![]() Digging deeper into how System 1 and System 2 thinking contribute to consumer choice

Digging deeper into how System 1 and System 2 thinking contribute to consumer choice

![]() Understanding the differences between explicit and implicit decision making

Understanding the differences between explicit and implicit decision making

![]() Clarifying why consumers may not be rational but can still be predictable

Clarifying why consumers may not be rational but can still be predictable

![]() Introducing judgment heuristics as an important nonconscious source of consumer decisions

Introducing judgment heuristics as an important nonconscious source of consumer decisions

![]() Explaining why persuasion often fails to play its expected role in influencing consumer choices

Explaining why persuasion often fails to play its expected role in influencing consumer choices

Up to this point in Part II, we’ve been constructing the background of brain science facts and findings that we need in order to answer the two big questions at the heart of neuromarketing: How do consumers decide what to buy? And why do we need neuromarketing to understand these decisions?

In this chapter, we answer these questions by, first, taking a deeper dive into Daniel Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2 models, with a specific focus on the very different ways these two systems operate in decision making. Then we look at two types of decisions — explicit and implicit — and examine their relative importance for consumer choice. Next, we introduce judgment heuristics (shortcuts and biases built into human decision-making systems), and show how these elements make consumer decisions both less rational and more predictable than previously realized. Finally, we take a fresh look at the topic of persuasion, and consider how all these new insights about decision making change our understanding of the role of persuasion in consumer choice.

How People Make Decisions

Decision making is the great mystery of human behavior. Every decision is a choice that, in principle, could have gone differently. It’s a fork in the road of behavior. Standing before that choice, you can choose to go one way or the other, but after you’ve chosen, you can’t go back. Every human being knows what it feels like to make a decision. But what we generally don’t realize is why we make the choices we make. We’re very poor at identifying the sources of our decisions, especially when they’re the everyday choices we continually make as consumers.

The mystery of decision making drives market researchers nuts. A consumer stands at the shelf in the grocery store, and chooses to put product A in her shopping cart instead of product B. Why did she make that choice? Until recently, the only one way a researcher could answer that question was to ask the consumer directly.

![]() Our conscious brains are lazy controllers of our nonconscious minds, preferring fast, efficient, and easy solutions to deep deliberation.

Our conscious brains are lazy controllers of our nonconscious minds, preferring fast, efficient, and easy solutions to deep deliberation.

![]() We’re naturally curious and drawn to novelty, but we don’t quite trust it.

We’re naturally curious and drawn to novelty, but we don’t quite trust it.

![]() We do trust familiarity and make many of our decisions based on what’s most familiar.

We do trust familiarity and make many of our decisions based on what’s most familiar.

![]() We like things that are easy to process, to such an extent that we often mistake processing fluency for inherent goodness, truth, persuasiveness, safety, and likeability.

We like things that are easy to process, to such an extent that we often mistake processing fluency for inherent goodness, truth, persuasiveness, safety, and likeability.

![]() Our thinking is highly reliant on a process called priming, which links one idea to another both consciously and nonconsciously, and has a large impact on our chain of thought and reactions to the world around us.

Our thinking is highly reliant on a process called priming, which links one idea to another both consciously and nonconsciously, and has a large impact on our chain of thought and reactions to the world around us.

![]() Our judgments and preferences are highly influenced by emotional markers that operate largely below our conscious awareness and have significant impacts on what we notice and what we remember.

Our judgments and preferences are highly influenced by emotional markers that operate largely below our conscious awareness and have significant impacts on what we notice and what we remember.

![]() We’re often motivated by goals we aren’t aware that we’re pursuing, the success or failure of which affects our moods and performances in ways that are inaccessible to us.

We’re often motivated by goals we aren’t aware that we’re pursuing, the success or failure of which affects our moods and performances in ways that are inaccessible to us.

![]() Much of our behavior is governed by habits, which get triggered by environmental cues and play out without conscious thought, goals, or intentions.

Much of our behavior is governed by habits, which get triggered by environmental cues and play out without conscious thought, goals, or intentions.

Given all these nonconscious and automatic forces that operate outside the traditional domain of logical, thoughtful decision making, we shouldn’t be too surprised that consumer choice remains a mystery, and that the nice stories consumers tell market researchers often fail to match up with what actually happens in the marketplace.

Digging down into Kahneman’s System 1 and System 2

Daniel’s Kahneman’s System 1–System 2 model is a dual-process theory of mental activity that distinguishes between two very different types of thinking and deciding, corresponding roughly to the everyday concepts of intuitive response (System 1) and logical reasoning (System 2).

System 1: The fast and the furious

The defining features of intuitive System 1 decisions are spontaneity and effortlessness:

![]() Spontaneity: Intuitive thoughts seem to come to mind on their own, without any prompting or effort on our part. For instance, we can instantly recognize a face we haven’t seen in 20 years. We can put together a sentence without stopping to think about syntax or grammar. We can see a certain iconic red color and instantly think of Coca-Cola. Most thoughts and actions are normally intuitive in this sense and can be classified as products of System 1.

Spontaneity: Intuitive thoughts seem to come to mind on their own, without any prompting or effort on our part. For instance, we can instantly recognize a face we haven’t seen in 20 years. We can put together a sentence without stopping to think about syntax or grammar. We can see a certain iconic red color and instantly think of Coca-Cola. Most thoughts and actions are normally intuitive in this sense and can be classified as products of System 1.

The key to spontaneity is accessibility, the ease with which an idea comes to mind in our natural moment-to-moment flow of thought. We’ve identified several mental mechanisms that operate in System 1 to improve accessibility, such as priming, processing fluency, nonconscious goal pursuit, and habits.

The key to spontaneity is accessibility, the ease with which an idea comes to mind in our natural moment-to-moment flow of thought. We’ve identified several mental mechanisms that operate in System 1 to improve accessibility, such as priming, processing fluency, nonconscious goal pursuit, and habits.

![]() Effortlessness: Effortlessness is a very interesting quality of System 1 thinking, because only some properties of objects or situations are accessed effortlessly. These are called natural assessments. For example, System 1 experiences many physical properties such as size, distance, and loudness effortlessly. It also experiences many abstract properties effortlessly, such as similarity, cause and effect, and expectancy violation (surprise).

Effortlessness: Effortlessness is a very interesting quality of System 1 thinking, because only some properties of objects or situations are accessed effortlessly. These are called natural assessments. For example, System 1 experiences many physical properties such as size, distance, and loudness effortlessly. It also experiences many abstract properties effortlessly, such as similarity, cause and effect, and expectancy violation (surprise).

The effortlessness of System 1 thinking has an important implication for decision making. Ambiguity and uncertainty are suppressed in System 1. When only a single option comes to mind, and it does so rapidly and automatically, the “choice” it represents is practically foreordained. Often it isn’t seen as a choice at all, but as a natural next step in a linear and effortless flow of actions.

System 2: The slow and the methodical

The defining features of System 2 decisions are deliberate control and effortfulness. Compared to System 1, operations of System 2 are slower, require explicit mental effort, and are initiated and controlled voluntarily. Nothing happens spontaneously or automatically in System 2; all processes are consciously invoked and monitored.

The results of System 2 deliberation usually take the form of judgments or evaluations. System 2 is involved in all judgments, whether they originate in impressions (intuitive judgments) or reasoning (deliberate judgments).

An important quality of System 2 processes is that they’re single-threaded (that is, they come to mind one at a time). When a new deliberative thought occurs, it disrupts or interrupts the previous thought. So-called “multitasking” can only be accomplished in one of two ways: Either we consciously switch back and forth between different tasks within System 2, or we relegate a task to System 1 through practice or habit formation.

A key question is how System 1 and System 2 interact. The short answer is: System 2 monitors and sometimes overrides the activities of System 1. The interesting feature of this relationship is that this monitoring is usually very lax. System 2 allows many intuitive judgments generated by System 1 to be expressed, without doing a lot of error checking. This is another feature that is critical to understanding how consumers decide.

Understanding explicit and implicit decisions

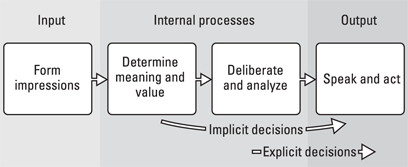

Figure 8-1 shows how explicit and implicit decisions map onto our model of brain processes from Chapter 2.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-1: Explicit and implicit decisions.

Explicit decisions result from conscious, System 2 deliberation. Of the many types of conscious thinking we engage in all the time, the mental activities of planning, reasoning, evaluating, simulating, and, of course, the experience of deciding itself, all play a role in explicit decision processes.

Implicit decisions, in contrast, bypass conscious deliberation. They’re driven by automatic, effortless System 1 processes that often don’t feel like decisions at all. Two types of implicit decisions are discussed in the academic literature on choices and behavior:

![]() Reflexive implicit decisions: Both the trigger and the resulting choice are nonconscious and automatic, such as when we automatically jump out of the way when we see a shape that might be a snake in the grass.

Reflexive implicit decisions: Both the trigger and the resulting choice are nonconscious and automatic, such as when we automatically jump out of the way when we see a shape that might be a snake in the grass.

![]() Intuitive implicit decisions: We’re aware of making the choice, but we can’t quite determine why or how we made it. For example, the decision to “like” or “not like” a new acquaintance is often intuitive in this sense. This type of implicit decision is more relevant to consumer decision making.

Intuitive implicit decisions: We’re aware of making the choice, but we can’t quite determine why or how we made it. For example, the decision to “like” or “not like” a new acquaintance is often intuitive in this sense. This type of implicit decision is more relevant to consumer decision making.

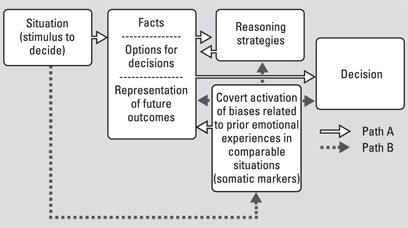

Explicit decisions: Emotions are still behind the wheel

In the traditional rational consumer model, emotions and intuition are often viewed as obstacles to making rational decisions. They’re seen as getting in the way of good decisions, luring consumers to make bad choices based on temptation and irrelevant decision criteria. What the new brain sciences tell us is that emotions and intuition are actually essential to explicit decision making. As we describe in Chapter 6, studies of patients with damage in the emotional processing centers of their brains show that their ability to make decisions is severely compromised. Instead of being rational Mr. Spocks, they’re perpetual ditherers, unable to make up their minds and settle on a choice.

The dilemma for market researchers is obvious: Emotions drive decisions — even explicit decisions — but we don’t have conscious access to many of those emotional drivers. When researchers ask people why they made a particular decision, they query their memory and come up with a plausible answer, but that answer will most likely be wrong.

![]() Treat people’s self-reports about why they made decisions with extreme caution. They’re probably rationalizing their decisions, not explaining them.

Treat people’s self-reports about why they made decisions with extreme caution. They’re probably rationalizing their decisions, not explaining them.

![]() Find and adopt measurement techniques that give you access to the nonconscious drivers of decisions. This is the only way you’ll have any chance of understanding why people actually make the decisions they make.

Find and adopt measurement techniques that give you access to the nonconscious drivers of decisions. This is the only way you’ll have any chance of understanding why people actually make the decisions they make.

Implicit decisions: The bread and butter of consumer decision making

One of the hardest things for traditional market researchers to accept is that much of the time consumers make decisions with very little conscious thought. Not only are emotions an important driver of these decisions, but emotions essentially are the decision.

Human brains are cognitive misers. Thinking is hard and we try to avoid it if we can. Emotional cues and triggers are attractive decision-making aids for our cognitive-miser brains because they provide easy shortcuts that allow us to make a decision quickly, without a lot of cognitive exertion. Easy decisions are fast decisions, and fast decisions give our brains time to do other things, like daydream, replay past experiences, and ponder our destinies.

This is the problem that market researchers face every day. Consumers simply don’t play the game the way they “should.”

Why Consumer Decisions Aren’t Rational

The traditional view of marketing and consumer choice goes something like this: People have preferences. When faced with choices, they consult their preferences in memory and make judgments about what to do. Then they make their choices based on those judgments. If you’re in the business of trying to influence people’s choices — that is, if you’re in marketing — you’re taught to do this by sending people messages containing arguments that you hope will persuade them to change their preferences and judgments and, as a result, change their choices.

There are two weak links in this chain of reasoning:

![]() The assumption that preferences are stable, persistent over time, and available before a choice opportunity appears

The assumption that preferences are stable, persistent over time, and available before a choice opportunity appears

![]() The assumption that these stable preferences produce equally stable judgments, which can be recorded reliably in surveys and will translate into consistent and predictable choices and behaviors

The assumption that these stable preferences produce equally stable judgments, which can be recorded reliably in surveys and will translate into consistent and predictable choices and behaviors

The verdict of extensive brain science research is that neither of these assumptions is correct. Instead:

![]() Consumer preferences are seldom stable and persistent. On the contrary, they tend to be constructed in the moment of choice and are highly context sensitive, meaning they can be easily reversed by changing the context of the choice, the alternatives presented, or other factors external to the choice itself.

Consumer preferences are seldom stable and persistent. On the contrary, they tend to be constructed in the moment of choice and are highly context sensitive, meaning they can be easily reversed by changing the context of the choice, the alternatives presented, or other factors external to the choice itself.

![]() Similarly, judgments and choices are highly sensitive to seemingly minor differences in context, such as presence of other people, cognitive distractions, time pressures, and nonconscious primes. In addition, they’re subject to predictable biases imposed by judgment heuristics (discussed in the next section) that appear to be built into our System 1 decision-making processes.

Similarly, judgments and choices are highly sensitive to seemingly minor differences in context, such as presence of other people, cognitive distractions, time pressures, and nonconscious primes. In addition, they’re subject to predictable biases imposed by judgment heuristics (discussed in the next section) that appear to be built into our System 1 decision-making processes.

An example of the fragility of preferences and choices is provided by a study published by Jonah A. Berger and Gráinne Fitzsimons in The Journal of Marketing Research in 2008. In one experiment, participants were asked to complete a survey of product preferences that included some products that were orange in color, some that were green, and others that were neither orange nor green. Participants were randomly given a pen with either orange or green ink to complete the survey. Those who filled out the survey using green-ink pens chose more green than orange products, and those who used orange-ink pens chose more orange than green products.

Judgment heuristics: The way we’re wired

Beginning with Kahneman and Tversky in the 1970s, behavioral economists have studied how we use judgment heuristics (evaluative shortcuts) to size up situations in which we make decisions. Here are some examples and implications for consumer marketing and behavior:

![]() Loss aversion: We don’t value gains and losses equivalently. On average, stock traders sell gaining stocks sooner than they should, and hold losing stocks longer than they should. For consumers, offers expressed in terms of avoiding losses — such as “limited-time” offers — are more likely to be accepted than the same offers expressed in terms of achieving gains.

Loss aversion: We don’t value gains and losses equivalently. On average, stock traders sell gaining stocks sooner than they should, and hold losing stocks longer than they should. For consumers, offers expressed in terms of avoiding losses — such as “limited-time” offers — are more likely to be accepted than the same offers expressed in terms of achieving gains.

![]() Anchoring: We like to make relative, not absolute, estimates. Put a $30 bottle of wine next to a $130 bottle, and we’ll probably buy it. Put the same bottle next to a $20 bottle, and we probably won’t buy it. Anchoring is used regularly in consumer product pricing, such as when an infomercial announces, “You would expect to pay $49 for a knife like this!”

Anchoring: We like to make relative, not absolute, estimates. Put a $30 bottle of wine next to a $130 bottle, and we’ll probably buy it. Put the same bottle next to a $20 bottle, and we probably won’t buy it. Anchoring is used regularly in consumer product pricing, such as when an infomercial announces, “You would expect to pay $49 for a knife like this!”

![]() Framing: Put a message in the right frame, and it practically sells itself. Call a tax an “estate tax,” and 80 percent of the public are for it, because only rich people have estates. Call it a “death tax,” and 80 percent are against it, because the government shouldn’t be able to tax people just because they died. Consumers show consistent biases based on linguistic framing. For example, consumers will consistently prefer “75 percent lean ground beef” to “25 percent fat ground beef” even though the two options are equivalent.

Framing: Put a message in the right frame, and it practically sells itself. Call a tax an “estate tax,” and 80 percent of the public are for it, because only rich people have estates. Call it a “death tax,” and 80 percent are against it, because the government shouldn’t be able to tax people just because they died. Consumers show consistent biases based on linguistic framing. For example, consumers will consistently prefer “75 percent lean ground beef” to “25 percent fat ground beef” even though the two options are equivalent.

![]() Default bias: We’re suckers for defaults. Countries where people have to check a box to volunteer to be organ donors average about 5 percent participation. Countries where people have to check a box to not volunteer to be organ donors average about 80 percent participation. For consumers, defaults are particularly effective for subscription services in which the default is to renew the subscription but special action is required to cancel the subscription.

Default bias: We’re suckers for defaults. Countries where people have to check a box to volunteer to be organ donors average about 5 percent participation. Countries where people have to check a box to not volunteer to be organ donors average about 80 percent participation. For consumers, defaults are particularly effective for subscription services in which the default is to renew the subscription but special action is required to cancel the subscription.

![]() Affect heuristic: If we like something, we use that liking as a substitute for more difficult assessments. People use emotional responses as stand-ins for more complex risk assessments, frequency estimates, safety evaluations, and even predicting future economic performance of different industries. For consumers, affect (simple liking or disliking) is often used to avoid considering complex combinations of risk and benefit, substituting positive or negative feelings for making the difficult logical calculations.

Affect heuristic: If we like something, we use that liking as a substitute for more difficult assessments. People use emotional responses as stand-ins for more complex risk assessments, frequency estimates, safety evaluations, and even predicting future economic performance of different industries. For consumers, affect (simple liking or disliking) is often used to avoid considering complex combinations of risk and benefit, substituting positive or negative feelings for making the difficult logical calculations.

![]() Endowment effect: We treat things we have as more valuable than things we don’t have. People were asked how much they would pay for an ordinary coffee mug. The average answer was $3. Other people were given an identical coffee mug as a gift, and then asked how much they would sell it for. The average answer was $7. For consumers, this effect is often seen in bundling sales strategies. Car buyers end up buying more options if they start with a fully loaded model and remove options they don’t want, as opposed to starting with a no-options model and adding the options they do want.

Endowment effect: We treat things we have as more valuable than things we don’t have. People were asked how much they would pay for an ordinary coffee mug. The average answer was $3. Other people were given an identical coffee mug as a gift, and then asked how much they would sell it for. The average answer was $7. For consumers, this effect is often seen in bundling sales strategies. Car buyers end up buying more options if they start with a fully loaded model and remove options they don’t want, as opposed to starting with a no-options model and adding the options they do want.

Including judgment heuristics in consumer decision-making models

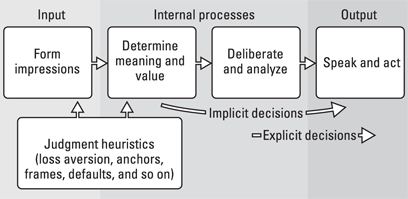

Judgment heuristics are so important to understanding consumer decisions that we’re going to have to supplement our conscious-nonconscious processing model from Chapter 2 to include them.

As illustrated in Figure 8-2, judgment heuristics impact the first two phases of cognitive response: impression formation and determining meaning and value. As aids to judgment, heuristics are particularly influential in the nonconscious attribution of value. They help consumers intuitively assign value to options and alternatives, thereby making decisions easier and faster, and encouraging immediate action (fulfilling our wants and needs right now) over time-consuming deliberation.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-2: Including the impact of judgment heuristics on consumer decision making.

An important feature of judgment heuristics is that they work well most of the time, but because they bypass conscious deliberation, they sometimes produce suboptimal results. Another way to say this is that heuristics introduce errors and biases into our decision making that can cause us to come up with choices that differ from what a perfectly rational consumer would do. Loss aversion, for example, causes us to pay more to avoid losses than we “should” be willing to pay if we were completely rational.

The upshot is that human beings may not be rational decision makers, but they are predictable decision makers. This is the idea behind the title of Dan Ariely’s popular book on behavioral economics, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions (Harper Perennial). Because judgment heuristics seem to be universally built into our System 1 processing machinery, we all respond pretty much the same to similar situations. Clever marketers who are aware of these heuristics can modify a consumer’s environment to encourage decisions that favor their brands and products over competitors’. This is one of the main avenues of marketing innovation that neuromarketing is currently supporting.

Careful exploitation of anchors, frames, defaults, and other heuristic stimuli in a shopping environment can have at least as much impact on sales as the most persuasive advertising message. All these tactics can be derived from an understanding of how the brain actually perceives and interprets the world and makes decisions. As such, they’re all targets in the research sights of neuromarketing.

The Limits of Persuasive Messaging in Consumer Decision Making

To directly persuade a consumer to buy your product, you need to grab her attention, make her listen to what you have to say, and then get her to remember your argument the next time she has an opportunity to make a purchase. That’s a tall order with many steps, quite a bit of cognitive responsibility required from consumers, and many potential points where the process can break down.

The new perspective that brain science brings to this challenge is twofold:

![]() It tells marketers and market researchers why persuading people with arguments and claims is so hard to do, given how the intuitive consumer actually thinks and makes decisions.

It tells marketers and market researchers why persuading people with arguments and claims is so hard to do, given how the intuitive consumer actually thinks and makes decisions.

![]() It presents the intriguing possibility that all this effort may be beside the point. Persuasive messaging may be overrated as a marketing mechanism.

It presents the intriguing possibility that all this effort may be beside the point. Persuasive messaging may be overrated as a marketing mechanism.

In this section, we consider some of the challenges that persuasive messaging faces as a mechanism for influencing the attitudes and behaviors of intuitive consumers.

Persuasion versus implicit consumer decisions

Implicit consumer decisions bypass conscious deliberation. These decisions are experienced without any internal questioning or weighing of arguments, leaving no opportunity for persuasive messaging to influence the decision’s outcome, at least not in a way the consumer would be consciously aware of and would be able to articulate to a researcher.

Persuasion certainly can play a role in such decisions, but its impact is likely to be nonconscious and situational, not conscious and logical. For example, consumers may be persuaded to buy a product because they believe it’s in short supply or because it’s endorsed by an authority figure, but they’re more likely to rely on situational and environmental cues in coming to these conclusions, not persuasive arguments.

Given the onslaught of persuasive messaging that consumers are exposed to in their everyday lives, there is evidence that explicit persuasion efforts may generate an automatic and nonconscious counter-persuasion reaction in many consumers. Even an innocuous persuasive message like a retail store slogan has been found to trigger counter-marketing goals and behaviors in consumers (see the discussion of this research in Chapter 7).

These findings have important implications for advertising, which is viewed by many practitioners as first and foremost a marketing vehicle for persuasive messaging. According to this view (a part of the rational consumer model described in Chapter 2), the purpose of an ad is to deliver a persuasive message in a creative way so viewers will notice and remember the message at a later point in time when they’re considering a purchase.

The most surprising thing about these influences is how non-logical they are. To decide to buy a product because it satisfies a nonconscious goal, triggered by a random prime, encountered in a logically unrelated context, is the height of irrationality. Yet such misattribution seems to be a pervasive source of consumer decisions and actions — when they’re driven by System 1 thinking.

![]() It must activate System 2 processing, which is a difficult task in itself, due to the lazy control that System 2 provides over System 1.

It must activate System 2 processing, which is a difficult task in itself, due to the lazy control that System 2 provides over System 1.

![]() When System 2 is awakened, the argument must pass the logical filters, if-then rules, experience matching, simulation, and counter-arguments that System 2 will apply to it.

When System 2 is awakened, the argument must pass the logical filters, if-then rules, experience matching, simulation, and counter-arguments that System 2 will apply to it.

All in all, a tough sell.

Gary Klein is a researcher who has studied implicit decision making (which he calls “intuitive decision making”) in a wide variety of occupations — business executives, firefighters, nurses, soldiers. In his book, The Power of Intuition: How to Use Your Gut Feelings to Make Better Decisions at Work (Crown Business), Klein estimates that about 90 percent of our decisions are intuitive. Assuming that this ratio holds for consumer decision making as well, marketers and market researchers are faced with the challenge that their traditional model of persuasion is relevant in only about 10 percent of the decisions they want to understand and influence. For the remaining 90 percent of consumer decision making, different measurement techniques are required, and that’s where neuromarketing comes into the picture.

Persuasion versus judgment heuristics

Judgment heuristics operate as a part of System 1 processing. Because they impact decisions and actions below the level of conscious awareness, they aren’t subject to the limits encountered by persuasive messaging. Judgment heuristics are essentially unfair competitors of persuasive messaging. By simplifying decision making with intuitive shortcuts and estimations, they make mental escalation to conscious deliberation unnecessary, thus providing an alternative path to choice and action that can easily render the most earnest persuasion effort irrelevant.

As behavioral economics has become more mainstream in the last decade, thanks to the popularity of books like Daniel Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) and Dan Ariely’s Predictably Irrational (Harper Perennial), marketers have become more aware of judgment heuristics and more sophisticated in their use. This is especially true in shopping, retail, and dining contexts, where immediate consumption or acquisition can be channeled in desired directions with careful attention to factors such as store layout, the proximity of competing products, the order in which items are viewed, pricing options, or the availability of decoy alternatives (alternatives offered for the sole purpose of making other offers appear more attractive). Such manipulations of choice architecture (the way in which choices are presented to encourage different selection outcomes) can be used to trigger judgment heuristics and steer consumer choice in one direction or another.

Here are some examples using the anchoring heuristic:

![]() In an experiment conducted in a convenience store where the average purchase was $4, some customers were given a coupon that offered $1 off any purchase of at least $6, while others were given a coupon that offered $1 off any purchase of at least $2. Not only did customers who received the $6 coupon spend more than average, but customers who received the $2 coupon actually spent less. The coupon created an anchor effect from which people nonconsciously adjusted their spending.

In an experiment conducted in a convenience store where the average purchase was $4, some customers were given a coupon that offered $1 off any purchase of at least $6, while others were given a coupon that offered $1 off any purchase of at least $2. Not only did customers who received the $6 coupon spend more than average, but customers who received the $2 coupon actually spent less. The coupon created an anchor effect from which people nonconsciously adjusted their spending.

![]() In fast-food restaurants, the introduction of extreme food sizes (for example, five-patty hamburgers) has been found to increase the choice of slightly less “supersized” options (such as three-patty hamburgers) by providing a new anchor point that makes the previously most extreme option seem less extreme.

In fast-food restaurants, the introduction of extreme food sizes (for example, five-patty hamburgers) has been found to increase the choice of slightly less “supersized” options (such as three-patty hamburgers) by providing a new anchor point that makes the previously most extreme option seem less extreme.

![]() A similar logic is often used in pricing, in which an anchoring effect is created by including an extremely high-priced alternative in the consideration set, thereby making alternatives that were previously viewed as high-priced appear more moderately priced in comparison.

A similar logic is often used in pricing, in which an anchoring effect is created by including an extremely high-priced alternative in the consideration set, thereby making alternatives that were previously viewed as high-priced appear more moderately priced in comparison.

![]() Warehouse stores often use the technique of conspicuously displaying high-priced items like large-screen TVs and jewelry at the front of the store to reduce resistance to purchase less-expensive items elsewhere in the store.

Warehouse stores often use the technique of conspicuously displaying high-priced items like large-screen TVs and jewelry at the front of the store to reduce resistance to purchase less-expensive items elsewhere in the store.

In each of these cases, consumer choice is influenced nonconsciously, via activation of a judgment heuristic as part of an implicit decision process. As long as the consumer isn’t aware that his or her decision is based on a nonconscious heuristic, persuasive messaging is likely to be irrelevant to the decision. Asking consumers if an ad or other persuasive message had an impact on their choice is, therefore, beside the point. They may say yes or no, but the answer is probably unrelated to the decision process that actually occurred.

Although there is evidence that consumers can activate nonconscious correction goals to resist persuasive messaging (discussed in Chapter 7), the same correction mechanisms may not work for resisting nonconscious judgment heuristics or other decision influences like priming and processing fluency. Evidence from hundreds of nonconscious processing experiments supports the conclusion that System 2 override is necessary to counteract the effects of System 1 heuristics. In other words, if consumers aren’t consciously aware of the impact of judgment heuristics on their choice behavior, they can’t compensate for those impacts.

Persuasion versus habit

Finally, persuasion must compete with habit.

As described in Chapter 7, habits don’t require supporting goals — conscious or nonconscious — or intentions to be activated. Habits arise from repetition, are triggered by environmental cues, and play out in an automatic way without conscious oversight. Changing habits through persuasive messaging has generally been found to be ineffective, to a large degree because of the misalignment between trying to impact a nonconscious process by activating a conscious process. The two do not connect.

Research on habits reveals that about 45 percent of people’s day-to-day activities is repeated almost daily, usually in the same physical location. Repetition is also extremely prevalent in consumer behavior. As summarized by researchers Wendy Wood and David T. Neal in “The Habitual Consumer” (Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2009):

![]() Consumers tend to buy the same brands of products across different shopping episodes.

Consumers tend to buy the same brands of products across different shopping episodes.

![]() Consumers purchase the same amounts at a given retail store across repeat visits.

Consumers purchase the same amounts at a given retail store across repeat visits.

![]() Consumers eat similar types of foods at a meal across days.

Consumers eat similar types of foods at a meal across days.

![]() These habits have significant financial impacts for product companies. Increases in repeated purchase and consumption are linked with increases in market share of a brand, customer lifetime value, and share of wallet.

These habits have significant financial impacts for product companies. Increases in repeated purchase and consumption are linked with increases in market share of a brand, customer lifetime value, and share of wallet.

The key characteristic of habits is that they’re rigid. They tend to be carried out in the same way even if goals or contexts change. As a result, habits change only slowly over repeated experiences.

Ehrenberg’s views were not well received by the marketing community when he presented them, and they remained a minority opinion for several decades. But recent brain science, including our understanding of System 1 and System 2 processing, provides a stronger foundation for ideas such as Ehrenberg’s. We address these issues in our discussion of neuromarketing and advertising in Chapter 11.

Market researchers used to believe that consumer decisions were based on rational calculations using available information to balance costs and benefits. According to this rational consumer model (introduced in

Market researchers used to believe that consumer decisions were based on rational calculations using available information to balance costs and benefits. According to this rational consumer model (introduced in

Modern brain science tells us two important things about explicit decision making:

Modern brain science tells us two important things about explicit decision making: The brain science research we’ve reviewed does not support this view. It paints a very different picture of advertising effectiveness, in which priming (not attention) is the primary mechanism by which advertising influences us. The way consumers infer the relevance of an ad to their needs and interests is not by deliberately processing a persuasive argument, but by picking up clues and cues from attributes such as familiarity, processing fluency, emotional markers, and nonconscious goal activation.

The brain science research we’ve reviewed does not support this view. It paints a very different picture of advertising effectiveness, in which priming (not attention) is the primary mechanism by which advertising influences us. The way consumers infer the relevance of an ad to their needs and interests is not by deliberately processing a persuasive argument, but by picking up clues and cues from attributes such as familiarity, processing fluency, emotional markers, and nonconscious goal activation.