Chapter 9

Brands on the Brain

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding how connections in the brain build strong brands

Understanding how connections in the brain build strong brands

![]() Seeing how successful brands influence us

Seeing how successful brands influence us

![]() Discovering how strong brands create lasting market impact

Discovering how strong brands create lasting market impact

![]() Identifying ways to test and build stronger brands

Identifying ways to test and build stronger brands

One of the most elusive concepts in the field of marketing and advertising is the notion of a brand. Ask consumers to describe what a brand means to them, and you’ll get a wide range of responses. Traditional market research must make a leap from those stated responses to predicting the outcomes of interest to marketers, such as how brands impact product impressions, choices, and ultimately, purchasing behavior. Because much of the impact of brands on consumer choice and behavior is nonconscious, this exercise in interpreting the tea leaves of consumers’ articulated utterances can easily go astray — too often, consumers simply don’t act the way they say they’re going to act.

In this chapter, we show how brands are represented in the brain, and how those representations can be reinforced or changed by marketing. We begin with a discussion of brands and memory, describing how people’s experiences with brands get converted into long-term brand associations and loyalty. We then consider how consumers can be influenced by brands at a nonconscious level and how brand-building occurs over time. Next, we look at why leading brands are so hard to displace, and how upstarts can still sometimes displace them. Finally, we summarize how neuromarketing measures can be used to study the impact of brands on the brain.

Brands Are About Connections

A brand has physical aspects, like a logo or slogan or spokesperson, but at its core, it’s an idea that exists in the minds of people. The most important element of this idea is how it’s connected to other ideas and feelings in people’s minds. And those connections, in turn, are a function of a lifetime of experience with the brand, both direct (through actual usage) and indirect (through exposure to advertising, marketing, and the experiences of others).

Seeing brands everywhere

Studies have shown that children recognize hundreds of brands by the time they’re 3 years old and have opinions about thousands of brands by the time they reach their teens. By the time people become adults, they’ve amassed an enormous library of associations and impressions relating to brands.

Brands are deeply embedded in our brains because they help us make sense of the vast variety of products and services we’re exposed to every day in our lives as consumers. Because our brains are cognitive misers that seek out shortcuts to avoid deep, deliberative thinking and decision making, brands provide attractive alternatives to rethinking product decisions every time we’re faced with a choice. In effect, brands roll up a lifetime’s worth of experience (or at least an extended period of repeated direct and indirect experience) into a single summary representation of a variety of products under a single brand umbrella. They perform this semi-miraculous feat because marketers invest years of repetitive and carefully crafted exposures to teach us what their brands stand for. And we learn, even if we’re unaware of learning.

Understanding brand “equity” and connections in memory

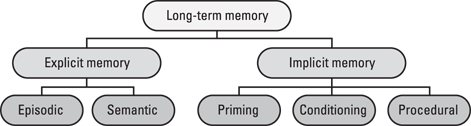

![]() Some brand memories are explicit and accessible. These are the memories a consumer can talk about when a researcher asks him for his opinions on brands and products.

Some brand memories are explicit and accessible. These are the memories a consumer can talk about when a researcher asks him for his opinions on brands and products.

![]() Other brand memories are implicit and inaccessible. These are the memories that influence a consumer’s behavior even though she isn’t aware of their influence, or even of their existence.

Other brand memories are implicit and inaccessible. These are the memories that influence a consumer’s behavior even though she isn’t aware of their influence, or even of their existence.

![]() These memory systems differ in two important ways. First, explicit memory is improved with attention, while implicit memory works just as well in the absence of attention. Second, explicit memories must be refreshed regularly to avoid being overwritten by new memories, while implicit memories can be much longer lasting without reinforcement.

These memory systems differ in two important ways. First, explicit memory is improved with attention, while implicit memory works just as well in the absence of attention. Second, explicit memories must be refreshed regularly to avoid being overwritten by new memories, while implicit memories can be much longer lasting without reinforcement.

Memories, both explicit and implicit, are highly networked. Each memory is associated with other memories — for example, your memory of the Coca-Cola brand (a semantic memory) may be associated with memories of quenching your thirst with an ice-cold bottle of Coke on a hot summer day when you were a young child in your hometown (an episodic memory). Experiencing the iconic Coca-Cola Santa Claus throughout your youth may have created an indelible connection in your mind (through conditioning) between Coke and Christmas. These associations are formed, strengthened, or weakened in memory every time you experience the brand — in an ad, in a store, or by using a product.

Brand equity is the value a company realizes from a product with a memorable brand name and positive, strong brand associations. Economic evidence shows that building brand equity leads to additional sales and better margins. A strong brand opens doors to intermediaries and potential partners and, thus, enables opportunities that are not available to brands with limited or no brand equity. Strong brands lift the value of the firms that own them, help those companies to attract the best talent, and provide them with a clear focus for marketing initiatives.

For example, the core concept of Red Bull (the brand) is the idea of an energy drink, a caffeinated beverage that is consumed for the purpose of boosting energy. This idea is associated in memory with a particular taste sensation, likely points of sale, preferred drinking occasions, various visual images (logo, colors, design concept, container), and other consumption-related memories, both semantic and episodic. But the brand has also carefully built broader connections in the minds of its consumers, such as an association with a daredevil attitude toward life, a love of extreme sports, and sponsorship of adventure events and promotions connected to the brand’s tag line and chief metaphor, “gives you wings.”

Marketers want to understand and, in many cases, change the content of those associations, their strength, and their connections to other concepts. Because of these associations, it’s possible to activate the brand memory indirectly (by activating a concept or emotion that is strongly linked to the brand memory). For example, viewing a TV program on adventure holidays may activate the Red Bull brand concept. The consumer may be aware of this, by consciously thinking of Red Bull, or it may be a nonconscious process.

Experiencing a brand

In the brain, neurons that are frequently activated together develop stronger connections, helping the memory become stronger in the consumer’s mind. But the reverse is also true: The connections between sets of neurons that are not activated together over a long period of time will get weaker. From the marketing perspective, this means that the brand memory needs to be activated regularly to ensure that the consumer doesn’t forget the brand. But the marketer also needs to activate desirable associations frequently in order to strengthen them.

Memory, as discussed in Chapter 6, is constructed, not simply retrieved. When the brand memory is activated, the brain re-assembles it by bringing the bits of information together. Some links, however, may be somewhat weak, and elements of the memory may be missed. The mind may fill holes in the memory by making assumptions and may embellish a brand memory that carries strong emotions.

This is why we can say with certainty that no memory is accurate. As time passes, it changes. The marketer’s challenge is to actively shape the consumer’s brand memory to increase the likelihood of purchase.

There are two ways brand memories can be updated:

![]() By direct experience with the brand, such as drinking Red Bull, wearing Nike shoes, or using an Apple iPad

By direct experience with the brand, such as drinking Red Bull, wearing Nike shoes, or using an Apple iPad

![]() By exposure to messaging about the brand, such as viewing advertising on TV, seeing other kinds of marketing messages like billboards or print ads, or talking with your friends about their experiences with the brand

By exposure to messaging about the brand, such as viewing advertising on TV, seeing other kinds of marketing messages like billboards or print ads, or talking with your friends about their experiences with the brand

The mechanism by which this effect occurs is expectations: Experiences and exposures to marketing create and update the consumer’s expectations about experiencing the brand in the future. Some researchers call this the placebo effect of brand expectations on product experience, because these expectations act like a placebo pill in a drug effectiveness test. In such tests, placebos often provide the same relief as the real drug, simply because people expect them to.

The classic neuromarketing demonstration of this effect was conducted by a team of Baylor University researchers in 2004. While study participants had their brains scanned in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanner (see Chapter 16), they performed a test made famous in Pepsi advertising in the 1980s called the “Pepsi Challenge.” In the advertising version of the test, people did a taste comparison of the two colas, not knowing which was which, and more often than not preferred the taste of Pepsi to Coke, even if they were loyal Coke drinkers. In the experiment, the researchers also conducted a slightly different test. They told participants they were drinking Coke (or Pepsi) and then compared brain scans of Coke loyalists and Pepsi loyalists while tasting the soft drinks.

Whichever cola participants were really tasting (the researchers mixed them up), when people thought they were drinking Coke, different areas of their brains were activated than when they thought they were drinking Pepsi. When tasting what they believed was Pepsi, areas of their brains associated with immediate reward, such as experiencing sweetness, were activated. But when tasting what they thought was Coke, additional areas were activated that were associated with positive emotions and explicit episodic memories.

The researchers’ interpretation: People’s associations of positive emotional memories with Coke, often formed over a lifetime of direct experience and marketing exposure, had a greater impact on their tasting experience than did the actual taste of the cola. Brand expectations affected brand experience more than brand experience affected brand expectations.

How Brands Impact Our Brains

Consumers may not be aware of the influence brands have on them, but encountering a known brand has significant effects on what consumers think and do. Exploring how brands impact nonconscious processes provides marketers with new insights they can use to raise the effectiveness of their brand strategies.

Activating nonconscious thinking with brands

In 2008, behavioral economists Dan Ariely and Michael Norton published an important article called “Conceptual Consumption,” in which they argued that academics and marketers could benefit from thinking about consumers as consuming not products but concepts.

Applying this idea specifically to branding, and changing their terminology just a bit, we can identify four categories of brand concepts that consumers can consume above and beyond physical consumption:

![]() Expectations: As we illustrate in the previous section, brand expectations can affect physical consumption at a level that can be observed in brain imaging studies. This effect can occur even if consumers are completely unaware of it.

Expectations: As we illustrate in the previous section, brand expectations can affect physical consumption at a level that can be observed in brain imaging studies. This effect can occur even if consumers are completely unaware of it.

![]() Goals: Brands can activate both conscious and nonconscious goals, and goals can have a big impact on people’s behavior (as we described in Chapter 7). Again, this effect can occur completely outside conscious awareness.

Goals: Brands can activate both conscious and nonconscious goals, and goals can have a big impact on people’s behavior (as we described in Chapter 7). Again, this effect can occur completely outside conscious awareness.

![]() Fluency: When people associate processing fluency with truth, beauty, liking, and familiarity (see Chapter 5), they are, in effect, gaining a sense of satisfaction from consuming that fluency rather than consuming a product that is presented fluently. This usually happens without any awareness of the effect.

Fluency: When people associate processing fluency with truth, beauty, liking, and familiarity (see Chapter 5), they are, in effect, gaining a sense of satisfaction from consuming that fluency rather than consuming a product that is presented fluently. This usually happens without any awareness of the effect.

![]() Values: When a brand is strongly associated with a value in people’s minds, such as the association between Red Bull and a daredevil attitude toward life, people may really be consuming that value when they’re consuming the product. Following research pioneered by psychologist E. Tory Higgins, Ariely and Norton call this regulatory fit between a value and a consumption experience. Values are like goals but more general. People feel better about themselves when the goals they pursue fit in well with larger values they embrace.

Values: When a brand is strongly associated with a value in people’s minds, such as the association between Red Bull and a daredevil attitude toward life, people may really be consuming that value when they’re consuming the product. Following research pioneered by psychologist E. Tory Higgins, Ariely and Norton call this regulatory fit between a value and a consumption experience. Values are like goals but more general. People feel better about themselves when the goals they pursue fit in well with larger values they embrace.

In each of these types of conceptual consumption, we often find explanations for consumer behavior that, on the surface, appear to be less than ideal from a purely rational consumer perspective. For example, people may happily consume food that’s objectively less tasty because they expect it to taste better (due to a strong brand association with tastiness), because it helps them to achieve a goal (like weight loss), because it comes in an especially easy-to-prepare form (ease of use), or because it represents a commitment to a higher value (such as promoting local food growers).

Faced with the problem of identifying nonconscious sources of consumer behavior, marketers and researchers have two paths open to them:

![]() Measure direct brain or body responses that provide clues about how people are responding nonconsciously to brands and related marketing materials.

Measure direct brain or body responses that provide clues about how people are responding nonconsciously to brands and related marketing materials.

![]() Measure behavioral responses, such as the actions people take in real or simulated buying situations after exposure to brands and related marketing materials.

Measure behavioral responses, such as the actions people take in real or simulated buying situations after exposure to brands and related marketing materials.

We discuss many examples of both approaches throughout this book, including the last section of this chapter. In the nearby sidebar, “Testing the Apple brand and creativity,” we describe a particularly innovative experiment that used a behavioral approach to assess brand associations and their impact on goal activation.

Brand-building over time

A brand is a concept stored in memory within a network of associations. Those associations must first be established; then they’re strengthened over time. It follows that brand-building is a long-term investment to establish the brand concept in the consumer’s memory and to create and strengthen the desired associations.

A new brand must stand out if it’s going to create a unique concept in the consumer’s mind. It must be seen as novel rather than familiar. But it can’t be seen as too novel, or it will trigger emotional resistance. The brand marketer must walk a fine line: Present the new brand concept as different enough to draw attention, but link it to positive emotional reactions by showing how it can address consumers’ goals and needs more effectively than competing brands already on the shelf.

Connecting brands to positive concepts in memory is time-consuming and expensive. Some brands try to take shortcuts around this process, and may achieve short-run successes as a result — for example, the brand that wins sales by copying the leading brand rather than differentiating, the brand that wins through distribution advantages rather than through its positioning, the brand that is simply bought on price, and so forth.

But the vast majority of new brands don’t succeed unless they manage to develop a distinctive brand concept in the consumer’s mind with strong, positive, and relevant associations connected to that concept. The well-known statistic on new product introductions — that 80 percent of new products fail — is testimony to the difficulty of this task.

![]() Exposure to the brand

Exposure to the brand

![]() Association with an emotionally positive concept

Association with an emotionally positive concept

![]() Reinforcement through repetition

Reinforcement through repetition

If you’re thinking, “That sounds like Pavlov’s dogs,” you’re right. This is the classic approach to conditioned learning. Just as Pavlov’s dogs were taught to salivate when they heard a bell ring, consumers are taught to associate brands and positive concepts, like the Apple and creativity example in the sidebar earlier in this chapter. After a brand and a concept are connected, that connection is strengthened every time either the brand or the concept is encountered, either directly (through experience) or indirectly (through messaging).

Growing brain-friendly brands

Conditioned learning is an implicit memory process. It occurs effortlessly and nonconsciously, so people aren’t aware of whether or how it’s operating. This means that marketers can’t ask people directly about the associations they’re forming with their brand.

![]() To trigger buying goals, make sure the brand and its associated concept are represented visually in close proximity to each other. Nonconscious processing is more readily activated by visual cues, which are more easily processed than written messages (due to processing fluency).

To trigger buying goals, make sure the brand and its associated concept are represented visually in close proximity to each other. Nonconscious processing is more readily activated by visual cues, which are more easily processed than written messages (due to processing fluency).

![]() A successful conceptual connection with a brand is often facilitated by strong, positive emotional associations. Motivating goals are the main drivers of purchase intention, but emotional connections are often key ingredients in the specific choice ultimately made.

A successful conceptual connection with a brand is often facilitated by strong, positive emotional associations. Motivating goals are the main drivers of purchase intention, but emotional connections are often key ingredients in the specific choice ultimately made.

![]() When a brand has strong associations with a purchase occasion, such as a holiday or lifecycle event, this is a good indication that it’s successfully reinforcing conceptual connections in its marketing and advertising.

When a brand has strong associations with a purchase occasion, such as a holiday or lifecycle event, this is a good indication that it’s successfully reinforcing conceptual connections in its marketing and advertising.

![]() High levels of customer satisfaction and loyalty are indicators that a brand is delivering consistently on consumer expectations whenever a purchase or consumption takes place.

High levels of customer satisfaction and loyalty are indicators that a brand is delivering consistently on consumer expectations whenever a purchase or consumption takes place.

![]() The more often and more radically a brand changes the conceptual connections communicated in marketing and advertising, the less likely it is to achieve reinforced long-term brand associations in memory. Conditioned learning is easily disrupted when one connection is replaced with another.

The more often and more radically a brand changes the conceptual connections communicated in marketing and advertising, the less likely it is to achieve reinforced long-term brand associations in memory. Conditioned learning is easily disrupted when one connection is replaced with another.

![]() Mature brands that depend only on familiarity to sustain their conceptual connections are at risk. Even established category leaders need to refresh their brand connections regularly in their consumers’ minds, either by strengthening existing associations or by developing new ones. A mature brand that isn’t skillfully combining novelty and familiarity in its messaging is at risk of seeing its conceptual connection deteriorate or be co-opted by upstart brands.

Mature brands that depend only on familiarity to sustain their conceptual connections are at risk. Even established category leaders need to refresh their brand connections regularly in their consumers’ minds, either by strengthening existing associations or by developing new ones. A mature brand that isn’t skillfully combining novelty and familiarity in its messaging is at risk of seeing its conceptual connection deteriorate or be co-opted by upstart brands.

Why Leading Brands Are So Hard to Displace

All the brand memory and activation processes we’ve been discussing in this chapter conspire to make leading brands extremely hard to displace.

Taking advantage of brand leadership

Brands fulfill a wide range of important functions. They increase familiarity and fluency for branded products. They provide shortcuts to choice when alternatives are difficult to compute. They shape expectations that can influence consumption and usage experiences. They provide assurances of consistency and quality for future purchases. And finally, they can invoke implicit emotional connections that impact attention, attraction, and memory activation.

A leading brand takes advantage of all these functions in a kind of self-reinforcing cycle: It has at its disposal a strong set of positive associations in consumers’ minds that make it more accessible in more circumstances than other brands in its category. Greater accessibility translates into more sales, which create wider distribution opportunities, greater word of mouth (including in social media), more editorial media coverage, superior product placement, shelf and display space in retail environments, more recommendations by sales staff, greater promotional activities by retailers and brand owners, and even access to better talent when it comes to recruiting members of the marketing team or appointing a creative agency. These advantages, in turn, increase the frequency and quality of the leading brand’s exposure to consumers, allowing it to produce more frequent and effective activations of the brand concept and its associations in consumers’ memory, resulting in even greater accessibility for the brand over time.

Leveraging habitual buying

One of the most powerful benefits leading brands have is their ability to take advantage of habitual buying. Habits, as discussed in Chapter 7, arise from repetition and are largely automatic. Unlike motivated behavior, driven by either conscious or nonconscious goal pursuit, habits do not require any form of intention or goal activation. Once the right situational cue is encountered, the habitual behavior script is triggered, and the action is carried out.

Much of everyday shopping is habitual. Although retail experts often say that 90 percent of purchase decisions are made in-store (see Chapter 12), in fact a large proportion of those purchases are not based on decisions (implicit or explicit) but instead are a function of habit. Even major purchases are often habitual. For example, many consumers automatically gravitate to the same automobile brand, or the same appliance brand, or the same mortgage provider. As the top seller in a category, the leading brand captures the lion’s share of this habitual buying.

Habits must be learned. There is always an initial choice process, which may even include some experimentation with different brands or product variations. The consumer then settles on a particular selection and, over time, habitual buying develops. Product selection becomes automatic: When supplies of brand A run low, the consumer “thoughtlessly” picks up more brand A on his or her next shopping trip. There is no considered decision.

![]() Maintain consistent triggers at the point of sale. Don’t change the situational cues that trigger habitual buying. Changing in-store displays and promotions can disrupt habitual behavior.

Maintain consistent triggers at the point of sale. Don’t change the situational cues that trigger habitual buying. Changing in-store displays and promotions can disrupt habitual behavior.

![]() Don’t ask your consumers to think. If they start thinking about the purchase, they may start thinking about alternative brands.

Don’t ask your consumers to think. If they start thinking about the purchase, they may start thinking about alternative brands.

![]() Don’t violate the habitual buyer’s expectations. Any change in any aspect of the product — price, placement, packaging, or ingredients — can disrupt habitual buying. Novelty attracts attention, attention leads to conscious deliberation, and deliberation can lead to consideration of alternatives.

Don’t violate the habitual buyer’s expectations. Any change in any aspect of the product — price, placement, packaging, or ingredients — can disrupt habitual buying. Novelty attracts attention, attention leads to conscious deliberation, and deliberation can lead to consideration of alternatives.

![]() Trigger behavior, not attitudes. Habitual buying is about activating a behavior with a situational cue, not remembering an attitude. Activating an attitude produces much less predictable results than activating a behavior.

Trigger behavior, not attitudes. Habitual buying is about activating a behavior with a situational cue, not remembering an attitude. Activating an attitude produces much less predictable results than activating a behavior.

As these guidelines imply, habitual buying can be disrupted. While the leading brand usually wants to maintain its own habitual buyers, and the upstart brand wants to disrupt the leader’s habitual buyers, disruption can be used by both leaders and upstarts. The challenge for either is to devise a strategy that disrupts the competitors’ habitual buyers, but not your own.

Understanding the upstart’s dilemma

So, what can a challenger brand do to deal with the habitual buying that favors the leading brand? Neuromarketers look to brain science for clues.

Disrupting a habitual buying cycle requires understanding the triggers and associations by which that cycle operates to the advantage of the leading brand.

According to product innovation expert Jean-Marie Dru, when the triggers and associations used by the leading brand are understood, the upstart’s objective should not be to disrupt that mental picture; instead, it should be to provide the consumer with a different set of desirable qualities that are not strongly associated with the leading brand, but can be associated with the upstart brand. This new set of concepts and associations then become mental territory that the upstart brand can dominate, creating and reinforcing a new network of associations that directs consumers to the upstart rather than the current leader.

One way to perform this neat trick is to take a page out of the conceptual consumption playbook — associate your upstart brand with a set of higher-order values that are important to consumers in the category, but are not referenced by other competing brands.

An example is provided in the dog-food category. For years, dog food was promoted on the basis of product qualities like vitamins, minerals, size of chunks, and meat content. The Pedigree brand disrupted this marketing convention by positioning itself at a higher level, declaring itself the “We’re for Dogs” brand with an emotional advertising campaign that said, in effect, “We love dogs more than any other dog-food brand does; if you love dogs, too, buy our brand.”

It would’ve been nearly impossible and probably self-damaging for Pedigree to try to unseat the leading brand by emphasizing even greater product quality. After all, the leading brand had developed strong product-quality associations in consumers’ minds, which were frequently activated and strengthened through extensive advertising, promotions, sponsorships, and packaging. To question these associations would’ve been risky, because it would’ve disrupted habitual buying throughout the category, including opening up questions about Pedigree’s own associations with product quality.

Instead, Pedigree focused its messaging on a new association with a value that was not linked to the leading brand (or to any other major brand), yet had a strong emotional connection to dog lovers. The resulting campaign was highly successful.

Often, disruption is not an option. In those cases, new brands are unlikely to succeed when simply following the strategy of the leader, which can maintain its “top of mind” status through simple emotional conditioning, using emotional connections, often in low-attention contexts, to reinforce positive associations and habitual buying triggers with its brand.

Although there are exceptions, like the early Pepsi follow-the-leader strategy (see “Experiencing a brand,” earlier in this chapter), more often than not, new brands need to adopt a different approach, one that shifts consumers from an implicit decision-making process to an explicit decision-making process:

![]() They must grab conscious attention.

They must grab conscious attention.

![]() They must explain why they should be considered for purchase, using deeper, more cognitively oriented messaging.

They must explain why they should be considered for purchase, using deeper, more cognitively oriented messaging.

![]() They must engage and satisfy counterarguments that regularly accompany conscious analysis of marketing claims. They don’t have the luxury of using reinforcement through low-attention processing.

They must engage and satisfy counterarguments that regularly accompany conscious analysis of marketing claims. They don’t have the luxury of using reinforcement through low-attention processing.

Using Neuromarketing to Test Brands

As we observed at the beginning of this chapter, branding is a natural research area for applying brain science insights and neuromarketing methods. In this section, we introduce some of the methods being used by neuromarketers today. We include a section like this at the end of each of the next five chapters in which we explore different application areas.

Measuring brand equity the old-fashioned way

Unfortunately, traditional market research has not produced a generally accepted way to measure brand equity. Many vendors are promoting their own proprietary brand-equity measures, but because brands end up with vastly different scores for each measure, none is considered definitive.

Most brand-equity measures depend in large part on accounting metrics such as market share, relative price, and lifetime customer value. Such measures are very useful for monitoring the progress of a brand’s marketplace performance, but they don’t shed light on the evolution of brand equity where it lives, in the mind of the consumer.

Some explicit brand concept mapping methodologies are available, but these are limited by their dependence on conscious consumer deliberation to identify associations with brands in memory. Such approaches introduce biases into the association-mapping process, because they encourage consumers to think about what connections should be made with a particular brand, instead of connections that naturally occur at a nonconscious level.

This is why the study of brand equity in the consumer mind, along with its consequences for consumer behavior, is such an ideal fit for neuromarketing tools and techniques.

Probing brand connections with neuromarketing

For neuromarketers, three key elements serve as a starting point for measuring brand equity:

![]() Associations: The nature and strength of the brand’s associations in memory

Associations: The nature and strength of the brand’s associations in memory

![]() Emotions: The emotional responses (positive-negative, arousal) triggered by the brand

Emotions: The emotional responses (positive-negative, arousal) triggered by the brand

![]() Motivations: The link between the brand and the consumer’s conscious and nonconscious goals

Motivations: The link between the brand and the consumer’s conscious and nonconscious goals

Neuromarketing provides several ways to measure brand associations. Some of these approaches measure behavioral responses; others measure changes in brain states that accompany activating strong associations in memory.

Behavioral approaches take advantage of a key property of associative activation in the brain (discussed in the section on priming in Chapter 5). When two ideas are closely associated in memory, activating one with an external cue (like presenting a word on a screen) makes activating the other easier and faster. So, the strength of association can be inferred behaviorally from various kinds of response-time studies (for more details on these techniques, see Chapters 16 and 17):

![]() Semantic priming: Two words are presented in rapid succession. The task is to classify the second word in some neutral way, such as whether it’s a real word or a fake word. The greater the association between the first and second words, the faster the participant will be able to classify the second word.

Semantic priming: Two words are presented in rapid succession. The task is to classify the second word in some neutral way, such as whether it’s a real word or a fake word. The greater the association between the first and second words, the faster the participant will be able to classify the second word.

![]() Implicit Association Test (IAT): A more complex classification test in which words or images are associated with different combinations of brand attributes at the same time, using a forced choice task. Response times are faster when the brand and attributes are positively associated in memory, and slower when they conflict with each other.

Implicit Association Test (IAT): A more complex classification test in which words or images are associated with different combinations of brand attributes at the same time, using a forced choice task. Response times are faster when the brand and attributes are positively associated in memory, and slower when they conflict with each other.

Brain state approaches measure changes in brain activity relating to the memory processes that get activated by strong associations in memory:

![]() Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): Studies using fMRI, such as the “Pepsi Challenge” study (see the “Experiencing a brand” section, earlier in this chapter), identify brain regions that attract greater blood flow when strong associations are triggered.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI): Studies using fMRI, such as the “Pepsi Challenge” study (see the “Experiencing a brand” section, earlier in this chapter), identify brain regions that attract greater blood flow when strong associations are triggered.

![]() Electroencephalography (EEG): Studies using EEG measure electrical signals in the brain associated with memory activation. A specialized application of EEG, called event-related potential (ERP) analysis, identifies brain-wave patterns — called ERP components — that emerge when sequentially presented words or images are strongly associated in memory. Several neuromarketing vendors use ERP components as part of their product offerings (for more on EEG and ERP, see Chapter 16).

Electroencephalography (EEG): Studies using EEG measure electrical signals in the brain associated with memory activation. A specialized application of EEG, called event-related potential (ERP) analysis, identifies brain-wave patterns — called ERP components — that emerge when sequentially presented words or images are strongly associated in memory. Several neuromarketing vendors use ERP components as part of their product offerings (for more on EEG and ERP, see Chapter 16).

Emotions are hard to measure with traditional verbal reporting, but several approaches to measuring emotional responses to brands are used by neuromarketers. Most nonconscious emotional responses to brand-related materials are immediate and automatic, so their valence (positive or negative direction) and arousal (intensity or level of stimulation) are best measured in the moment, rather than in later behavior. Neuromarketing methods for measuring emotional responses to brands include the following:

![]() Affective priming: Similar to semantic priming, this behavioral technique uses pairs of words rapidly shown one after the other. The second word is classified as positive or negative. The speed with which it is classified is a function of the emotional response to the first word.

Affective priming: Similar to semantic priming, this behavioral technique uses pairs of words rapidly shown one after the other. The second word is classified as positive or negative. The speed with which it is classified is a function of the emotional response to the first word.

![]() Electromyography (EMG): Studies using EMG measure facial micro-muscle movements that occur below the level of observable expressions. Certain muscles (such as the “frown” muscle and “smile” muscle) are especially sensitive to emotional reactions.

Electromyography (EMG): Studies using EMG measure facial micro-muscle movements that occur below the level of observable expressions. Certain muscles (such as the “frown” muscle and “smile” muscle) are especially sensitive to emotional reactions.

![]() Facial expression analysis: Automatic classification of observable facial expressions is available through several software programs, some of which can be implemented through webcams, with more or less reliable results (see Chapter 16).

Facial expression analysis: Automatic classification of observable facial expressions is available through several software programs, some of which can be implemented through webcams, with more or less reliable results (see Chapter 16).

Motivational goal activation by brands can be measured by neuromarketers both behaviorally and via brain measures:

![]() Behavior studies: As shown in Chapter 7 and the “Apple and creativity” study mentioned earlier in this chapter, participants can be primed with a brand in various ways and then exposed to an experimental situation in which their behavior indicates the extent to which that brand triggered specific types of goal seeking, either consciously or nonconsciously.

Behavior studies: As shown in Chapter 7 and the “Apple and creativity” study mentioned earlier in this chapter, participants can be primed with a brand in various ways and then exposed to an experimental situation in which their behavior indicates the extent to which that brand triggered specific types of goal seeking, either consciously or nonconsciously.

![]() EEG measurement of approach-avoidance: Neuroscientists have found that relative activation of certain brain-wave frequencies in the left and right frontal areas of the brain are reliable indicators of approach and avoidance motivation. Both academics and neuromarketers have developed metrics that use this indicator to measure degree of motivation in response to exposure to brands. This technique measures the activation of an approach-avoidance response, but it does not directly measure behavioral results of the activation.

EEG measurement of approach-avoidance: Neuroscientists have found that relative activation of certain brain-wave frequencies in the left and right frontal areas of the brain are reliable indicators of approach and avoidance motivation. Both academics and neuromarketers have developed metrics that use this indicator to measure degree of motivation in response to exposure to brands. This technique measures the activation of an approach-avoidance response, but it does not directly measure behavioral results of the activation.

These approaches can be used separately or combined in studies that use multiple measurement techniques to increase reliability by comparing different responses with each other.

Because consumers are largely unaware of how brands influence them, branding is a natural research area for applying brain science insights and neuromarketing methods.

Because consumers are largely unaware of how brands influence them, branding is a natural research area for applying brain science insights and neuromarketing methods.

You may assume that experiencing a brand directly would be the most powerful source of changing or reinforcing memory associations with the brand, but a large body of research shows that, surprisingly, it’s the experience that is often shaped by the existing memories, not the other way around.

You may assume that experiencing a brand directly would be the most powerful source of changing or reinforcing memory associations with the brand, but a large body of research shows that, surprisingly, it’s the experience that is often shaped by the existing memories, not the other way around. Over time, brands build connections in memory through the implicit memory process called

Over time, brands build connections in memory through the implicit memory process called  The marketing goal is to move a brand from novelty to familiarity and, ultimately, to an established habit, represented by habitual buying. As the process proceeds, the brand becomes associated with a promise in the mind of the consumer — to deliver on the expectations the consumer has developed through past exposures to the brand and the associated consumption experiences. The successful brand stands for consistency and satisfying established expectations.

The marketing goal is to move a brand from novelty to familiarity and, ultimately, to an established habit, represented by habitual buying. As the process proceeds, the brand becomes associated with a promise in the mind of the consumer — to deliver on the expectations the consumer has developed through past exposures to the brand and the associated consumption experiences. The successful brand stands for consistency and satisfying established expectations.