CHAPTER 4

Investing Responsibly

The Search for Similar Benefits for Ethical and Shariah Forms of Investing

Work not confusion in the earth after the fair ordering (thereof).

(Al Araf: 7)10

When the preclusive and the necessitated conflict, preference shall be given to the preclusive.

(Islamic legal maxim)10

INTRODUCTION

In June 2006, legendary investor Warren Buffett, the second richest man in the world after Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates, announced that he was giving most of his wealth to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, a foundation set up by Gates and his wife.1 The Gates Foundation asset trust endowment was $36.2 billion in September 2012, including $11 billion spread over seven installments to date.2

Subsequently, Buffett and Gates announced the Giving Pledge. Those who took it up committed to giving away at least half their fortune during their lifetime or after their death, and to publicly state their intention with a letter explaining their decision. Among those who signed the pledge were New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg; international fashion designer Diane von Fürstenberg; filmmaker George Lucas; and young billionaire Mark Zuckerberg, founder and CEO of global social networking phenomenon Facebook. Even China’s best-known philanthropist, Chen Guangbiao, joined the ranks and was the first of the country’s wealthy moguls to commit to giving away his money.

As societies become more affluent, they experience a migration of values. There appears to be a shift away from “materialist” values, which emphasize economic and physical security, toward “post-materialist” values, which emphasize self-expression and quality-of-life.

According to Boston Consulting Group’s (BCG) 11th annual Global Wealth report (May 2011), the world’s millionaires represent 0.9 percent of the world’s population but control 39 percent of the world’s wealth, up from 37 percent in 2009. Their wealth now totals USD47.4 trillion in investible wealth, up from USD41.8 trillion in 2009.3

These high-net-worth individuals, along with foundations and institutional investors, are keenly aware of the high social impact of ethical investments. In 2011, greenamerica.org reported that 85 percent of the money managers surveyed indicated that their clients have urged them to select more socially responsible or ethical investments for their portfolios.4

Socially responsible investing (SRI), which gives investors the opportunity to invest their money in alignment with their core beliefs, is an increasingly popular avenue for individuals who want to support and promote social good while achieving a good financial return on their investment. The interest in SRI extends to the average investor, who is able to see concretely what his or her savings will be invested into and ensure that the investment style is congruent with his or her ethical, consumer, and social values.

The concept of assimilating such ethical qualities into investment portfolios has always been the core of Shariah investing. Shariah investing can be considered a form of SRI because it excludes investment in businesses that are deemed unethical, such as those involved in gambling, alcohol, tobacco, pornography, and weapons. Interestingly, Shariah investing then goes beyond the traditional ethical investment screening approach to further integrate an additional layer of risk management with SRI ethical screening.

The Shariah-compliant investment process exercises prudence by excluding investments in highly leveraged companies from the portfolio. The screening process reinforces the principle that acceptable Shariah-compliant stocks should not be involved in excessive risk taking, high leverage, or exploitation of trade and commerce (muamalat) contracts. This investment approach is arguably more fiscally ethical, as it screens out financially risky stocks for a more stable and prudent alternative investment style. Overall, a Shariah-compliant portfolio will be less exposed to deleveraging and insolvency.

Having observed that most U.S., European, Japanese, and Australian pension houses have provided specific allocation to be invested in ethical and SRI portfolios, this chapter is designed to capture the interest of these pension houses and other ethical investors to benefit beyond a pure ethical investment. Shariah investing provides an additional quantitative filter by applying financial ratios to further qualify the suitability of securities whose business nature is Shariah-compliant. These financial ratios ensure that investible companies have low borrowing, manageable receivables, and productive use of cash. Those investible Shariah companies are therefore not only ethically screened but also financially stable and well-managed. A case-in-point was during the meltdown of global equity market in 2008, as an outcome of the crisis having caused a meltdown in the financial landscape. It also precipitated high global inflation as an outcome of increase in oil prices. The screening beyond ethical responsibility showed that during this period (October 2007 to March 2009), the Dow Jones Islamic Markets World Index performed a total return of 7.27 percent higher (down 43.21%) than the Dow Jones world Index (down 50.48%).4

This chapter looks at ethical and Shariah-based investing, giving an insight on how investors can invest using both investment methodologies in the future. Both faith (Shariah) investing and ethical investing involve the process of screening. While the Shariah screening is monitored by the Shariah scholars of the fund houses or index houses, the screening for ethical investments funds is monitored by a panel or committees responsible for setting the criteria and establishing an approved list of companies from which the portfolio manager can select investments. Ethical Investment Research Services (EIRIS), the United Kingdom’s leading independent provider of research into the ethical status of companies, also helps ethical funds with the ongoing monitoring of investments.

One factor in the growth of both SRI investment and Islamic investment is that the corporate world is becoming more sensitive toward shareholders’ increasing social awareness, and for it to operate by contributing toward increasing real economic activities. These are reactions toward challenges such as climate change, plus greed and extreme capitalism that have lately confronted the world into a combined environmental and economic crisis. Wal-Mart, for example, plans to reduce the amount of solid waste it creates, and to also sell sustainable products, such as energy-saving, low-mercury compact fluorescent light bulbs. Another example is Toyota, which issued Islamic bonds (Sukuk) in 2008. It is at the same time an International Organization for Standardization (ISO)–certified company supporting the growth of ethical investment by manufacturing energy saving and clean environment cars.

When it comes to Islamic fund portfolio management, similar to an ethical fund management portfolio, Islamic funds’ portfolios are managed using investment process philosophy, style, strategies, and themes based on Shariah principles and guidelines. Generally, these investment approaches are based on a solid, basic screening methodology by index providers or a custom made by investment managers themselves. These houses are further advised by their own boards of Shariah scholars, to ensure the investment parameters are indeed compliant. Presence of Shariah advisory boards is what makes Islamic funds’ portfolios perceived as credible investment.

Comparing the two platforms of fund management, Islamic fund management and ethical, there are a close parallels between Islamic and the ethical screening principles of fund management, notably with respect to the stock selection criteria for inclusion in portfolio.

SCREENING CRITERIA

The Shariah screening process encompasses two screening categories—namely, the qualitative sector screening using prohibited sectors and the financial screening using financial ratios.

Qualitative Sector Screening

When investing in Islamic funds, it is important for investors to be aware of the key principles guiding Islamic equity investment at all times. These include the legitimacy of investing in stock markets given the inherent uncertainty of equity prices and concern over ambiguity (gharar) in the information provided to investors. Investors also worry about the immorality of speculative activity and awareness of the temptation to get involved in restricted (haram) activities such as insider dealing, where those involved in buying and selling shares try to profit from information denied to other investors. As with ethical investment selection, both positive and negative criteria can be used. The Shariah screening will exclude nonpermissible activities (e.g., companies with major purpose of producing or distributing of alcohol, tobacco, gaming, pork products and conventional banking and insurance). Also, investment in conventional interest (riba)-based financial institutions is regarded as prohibited (haram).

Shariah advisory panels have made serious efforts to introduce screening criteria for investments to be able to meet the Shariah-compliance requirements. Shariah screening is generally made available by index houses such as FTSE, S&P Dow Jones, and MSCI, who in turn provide a wide spectrum of Islamic indices to be used as a benchmark by investment managers.

The Shariah Advisory Council (SAC) of the Securities Commission of Malaysia has drawn up detailed criteria for qualitative screening on companies to enable compliance with Shariah principles. Its criteria largely reflect those already adopted by the FTSE Islamic and S&P Dow Jones Indices. (The Dow Jones Islamic Market Index [DJIM] was the first attempt by any global index provider to create a measurement tool for Shariah-compliant investors and to reduce the research costs of ascertaining and measuring Shariah compliance by creating a global universe of Shariah screen companies approved by a Shariah supervisory board.) Investments are also prohibited in companies involved in production or sale of animal meat not slaughtered according to Islamic rituals. For example, the DJIM excludes any industry group that represents an incompatible line of business with Islamic principles. Those activities include tobacco, alcoholic beverages, pork, gambling, arms, pornography, hotel and leisure industry, and conventional financial services (banking, insurance, etc.).

The criteria for selection are essentially qualitative in the sense that they involve judgment rather than precise management. Similar to FTSE Islamic and DJIM financial ratio screening, the securities commission of Malaysia (SAC) has also implemented financial ratio for screening equities to ensure that they are Shariah compliant. These involve calculation of ratios, such as the proportion of interest-bearing debt to assets or the ratio of total debt to the average market capitalization of a company.

Financial Screening

In addition to qualitative sector screening, there are also concerns about investing in financially unhealthy companies (i.e., excessively indebted companies or firms that have significant treasury holdings and therefore substantial interest-based income).

The philosophy behind financial screening is to avoid trading in debt-embedded securities. Debt is not allowed to be traded other than at par. Therefore, in applying the Shariah principle, cash receivables and debt are not considered as an asset permitted for trade at discount or premium.

For a start, most listed global companies borrow from conventional banks and based on Shariah principles are meant to be excluded from Shariah compliance list. The Shariah scholars have therefore taken a pragmatic approach. They defer to reasoning (ijtihad), since there is no explicit reference to indicate the course of action in the Qur’an or Sunnah in limiting companies dealing with their financial transactions. Under such circumstances, Shariah requires that we “exercise your learned opinion,” or use reasoning to arrive at a ruling.5 Take S&P Dow Jones for example; it is now widely accepted by contemporary Islamic scholars advising S&P Dow Jones that if a company has bank borrowings that are in excess of one third of its market capitalization, then it is no longer Shariah compliant. This one-third ratio is also used to exclude firms that receive more than one third of their income from interest, usually in practice borrowing from conventional banks, but these are excluded in any case under the sector criteria.

Receivables are also an issue, as companies that extend significant supplier credits are in practice operating like banks, especially as receivables can be sold at a discount through factoring, with the discount given usually determined by interest rates. Firms with receivables that exceed one half of their market capitalization are therefore excluded.

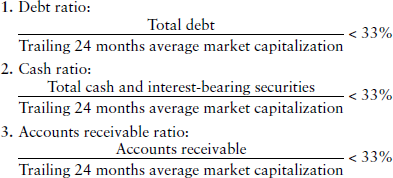

S&P Dow Jones Islamic Market Index has three (3) financial screens that must be administered for companies being Shariah compliant:6

In tandem with the financial ratios practiced by S&P Dow Jones, the FTSE Islamic index also adopts close to similar ratios, with the major difference that the base of ratios uses total assets, instead of market capitalization.

Using these ratios is very important for index providers because frequent changes in stock constituents without any underlying change in the nature of the business are likely to distort the index and its utility for benchmarking purposes. This approach gives investors the comfort that stocks do not pass the screening criteria as a result of market price fluctuation, allowing the methodology to be less speculative and more in keeping with Shariah principles.

To avoid distortion from compliance of the indices’ eligible components, both indexes are reviewed quarterly according to a consistent methodology. The review process is carried out by repeating the universe creation and component selection processes. In addition, the index is reviewed and audited on an ongoing basis, especially in case of new issues, crisis, bankruptcies, mergers, and so on.

Using S&P Dow Jones Islamic Market Indices ratios, it is therefore the Shariah board of S&P Dow Jones Islamic indices who are responsible to ensure that the investments are permissible (halal), but as specialists in this area of finance, with almost a decade of experience, they are arguably better qualified. Of course, the S&P Dow Jones Islamic Market Index does not have a monopoly in this area, as there are also the Financial Times Islamic Index, MSCI Islamic and FTSE Islamic Index.

As for Shariah advisory boards, there are banks like CIMB-Islamic based in Kuala Lumpur and Yasaar Limited with offices in Dubai and London who have expertise in this area through their composition of Shariah advisers.

The concept of equity investment is not, of course, Islamic, but it is permissible under Shariah, provided the companies selected are screened to ensure they are permissible (halal). Under the oversight of the Shariah advisory board, Islamic funds investment in most sectors is permissible, the major exclusions being conventional banks and insurance companies, companies involved in alcohol or port production, and media companies distributing pornographic content. S&P Dow Jones Islamic Finance Indices also exclude defense and weapons companies, whereas other index houses deal on these on a case-by-case basis.

Generally the exclusion of conventional banks in the screening contributes to the outperformance or underperformance in comparison to unscreened funds. When conventional banks are under distress and underperform the market, Shariah investment is expected to perform better. The case in point is the subprime crisis in the United States in 2007, which precipitated banks into a banking crisis during 2008–2009. The DJIM index, which excludes banks anyway, did outperform its conventional index DJ World Index.

SCREENING PROCESS FOR ETHICAL FORM OF INVESTING

Ethical investment funds use a screening process to ensure that the companies they invest in are the right ones to meet their ethical policy. The screening will remove companies considered to be negative and will encourage investment in “positive” companies. Examples of negative and positive criteria are examined along the following lines:

- Animal testing; for example, cosmetic finished products

- Genetic engineering

- Health and safety breaches

- High environmental concern, improvement, and management

- Human rights for basic social and economic rights

- Intensive farming with antibiotic residue

- Military and nuclear power

- Pesticides causing damage and death

- Pollution convictions

- Pornography and adult films

- Sustainable timber against deforestation

- Third-world concerns: profits before principles

- Community involvement via donations

- Corporate governance for accountability

- Disclosure of sufficient information

- Equal opportunities

- Positive products and services to build a safer world

- Supply chain issues, including working conditions

(For more information, refer to the Appendix at the conclusion of this chapter.)

The above criteria are oriented toward the support of recycling, renewable energy, cooperative housing, sustainable timber production, complementary health care, good workplace relations, and education. When we compare the qualitative investment restrictions for SRI and Islamic investment funds, similar companies whose principal activity is in weapons/war, products related to aborted human fetuses, pornography and obscenities in any form, and human cloning are also prohibited in Shariah. For ease of investors’ understanding, the Shariah ratio results in a second level of performance filter if compared to an ethical investing screening process. Naturally, the extra financial ratio screening will benefit the investors by bringing them to the next level, potentially getting better, sustainable, superior performance of their investments.

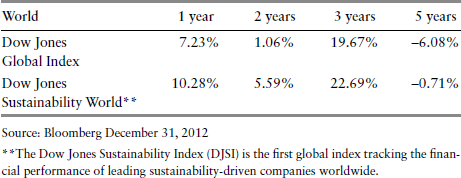

The Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) was launched in 1999 by Dow Jones indices and Sustainable Asset Management (SAM), a Swiss asset management company specialized in investing business and committed to social responsibility. The DJSI uses the methodology known as best in class that selects companies in each sector. The outperformance of DJSI relative to the global stock market indices supports the growing argument that practicing sustainability increases the value of the firm. Table 4.1 reflects better annualized returns derived from DJSI, which tracks SRI funds with the conventional Dow Jones Global Index.

Table 4.1 Total Return of Dow Jones Global versus SRI Index

SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE INVESTMENT VERSUS SHARIAH-COMPLIANT INVESTMENT

Socially responsible investment (also called ethical investment) focuses on good human, environmental, and social values. Islamic finance, by contrast, is the only example of a financial system directly based on the ethical precepts of a major religion; it provides not only investment guidelines, but also a set of unique investment and financing products.7 Therefore, Shariah investment is based on religious principles that include all values covered in SRI. Accordingly, if an investor is deemed comfortable with investing in SRI, the same investor will naturally become comfortable in investing in Shariah funds, which technically means investing in more financially stable companies considering that the financial ratios for the screening of Shariah companies is taking the process a step further than ethical screening by ensuring that the Shariah companies are low-leveraged, well-managed companies with limited downsides in a down-trending market. This means there is a quantitative risk overlay embedded in the equity investment process of a Shariah portfolio.

Both methodologies of investing have also established respective indexes. Although the benchmarks used for equity Shariah investment funds and Islamic indexes provided by S&P Dow Jones Islamic, FTSE Islamic, and MSCI Islamic, the indexes used by ethical investors and fund houses are created by international specialists in corporate responsibility (CR) and socially responsible investment (SRI) in the region. For example, the OWW Responsibility SRI Asia Index Series allows fund managers to offer passive management or index tracking products to their clients to bring Asian and Global SRI stocks into their portfolios quickly and at low transactions costs.8 Funds can track the constituents of this SRI Asia Indices in 100 percent Asia SRI Funds or can combine them with existing portfolios to create Global SRI Funds with an Asian component.

Just like faith (Shariah) investing, more and more people are taking an interest in ethical issues, covering subjects as diverse as environmental improvement, climate change, genetically modified food, gambling, and the destruction of rain forests. Nowadays, it’s possible to choose to actively support or avoid these causes through everyday activities such as buying organic food, donating to particular charities, or using recycled products. There are also increasing opportunities to make ethical choices when it comes to your finances.

If investors ever worry that the companies in which they invest might be exploiting the third-world countries or damaging the environment, or if they have concerns that they may be supporting company activities that they don’t approve of, they may be interested in ethical investment, or SRI. The similarities between Shariah-compliant investing and ethical investing provide an opportunity to use Shariah-compliant screens as a base for other ethically based investment strategies.

This goes to show that investors are able to have the best of both worlds by obtaining excellent financial returns while also supporting socially responsible companies.

Although there are many similarities in methodology between ethical and Shariah investing, there are also differences in executing the screening of the values—differences that are very marginal. In spite of these differences, the idea of excluding companies according to a set of ethical constraints is of mutual interest. Following is an easier read for investors in identifying more similarities than differences in investing in ethical and Shariah investments.

Similarities—Ethical and Shariah

There are indeed very little differences between investing in ethical and Shariah investments. If anything, Shariah investment is focused more on structures and faith-endorsed process, which at the end grants close to similar outcomes.

Whatever minimal differences in their approach, social investors share intent to act responsibly with their money and to try to achieve social objectives while reaching their financial aims. From being a value-based investing, aligned to one’s beliefs, the approach has now progressed toward value-seeking, which from a Shariah standpoint is derived from the strict limit in the financial ratios of investible companies.

Investors have also lately risen to the next level, seeking value-enhancement by engaging the shareholders of these companies to concentrate on corporate governance. Some of the differences are listed below.

Differences—Ethical and Shariah

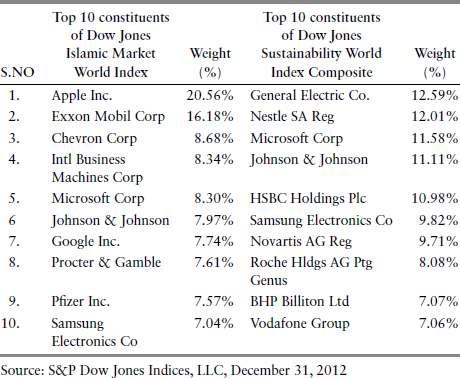

Having accepted these slight differences in methodology, let’s take a sample analysis of the constituents of the two indices, Dow Jones Sustainability World Index Composite and Dow Jones Islamic Market World Index (see Table 4.2). Worth noting is that 3 out of 10 constituents of both indices find their way into both Shariah and ethical investing.

Table 4.2 Top 10 Constituents for Shariah-Compliant and Ethical Investment Index under Dow Jones

A SIMILAR APPROACH TO YOUR INVESTMENT?

Islam is a blending of material and spiritual aspects of life. Therefore, Islam and all that stems from it frame a modus vivendi (lifestyle) to be observed in every aspect of life. So, if your modus vivendi states that gambling is forbidden, then investments in such, and in all other businesses that run contrary to Islam (alcohol, drugs, pornography, pork products, and financial services due to the prohibition on making money out of money) are also forbidden.

Similarly, ethical investment (SRI) can be considered as a modus vivendi for certain people, but only in temporal aspects of life, focusing on responsible investing that can take many similar forms. It is also important to bear in mind that different investors have different principles, and not all ethical investment funds have the same objectives. Some look to invest in companies that make a positive contribution, while others specifically avoid certain companies. Ethical investors may avoid companies involved in activities believed to be harmful, such as tobacco production and pornography, while others may wish to support companies that make positive contributions to society (by being environmentally friendly, for example). There are also ethical investment strategies that try to balance the avoidance of some activities with the proactive support of others.

However, for ease of reference, according to the Ethical Investment Association of Australia, the most established ways of investing ethically are:

- Negative screening. This means avoiding some types of investments, for example gambling companies or weapons manufacturers.

- Positive screening. This involves a preference for activities or characteristics deemed desirable (e.g., future-oriented industries such as renewable energy and health care).

- Best of sector. Leading firms in every business sector are selected based on their environmental and social performance or sustainability.

- Social responsibility overlay. Shares for a portfolio are selected in the usual way, but a process is added for addressing issues related to social responsibility.9

There are ethical funds that go further still by using shareholder pressure to bring about changes in company policy. By joining forces with other investors, some ethical funds have successfully influenced several companies to change their practices.

AVAILABILITY OF CHOICE FOR INVESTORS

Investors are spoiled with choices when deciding between ethical and Shariah investing because in an uncertain investment market, both have shown better performance than non-ethical and non-Shariah. For example: Between December 2007 and December 2012, the FTSE SRI Index (FTSE KLD 400 Social Index “TKLD400U”) outperformed the FTSE World Index (FTWI01) by 13.33 percent. In the same tone, Dow Jones Sustainability Index (W1SGI), which is a good measure of CSR companies around the world, outperformed the Dow Jones Global Index (W1DOW) by 5.13 percent.10

Interestingly, CSR-oriented companies in Malaysia returned more than three times the amount returned by CSR-oriented companies elsewhere in the world.

These high returns are creating huge demand from overseas investors for SRI investment vehicles in Malaysia, but unfortunately, there is not sufficient supply to meet this demand. This is a gap that investors can benefit from.

Although Shariah investing has progressed into establishing standards, index, research, accreditation, and transparency and covenants, ethical and SRI investment funds have also managed to operate within an established global framework. Examples of the larger international specialists who are offering research, forms of reference, and reporting for the ethical and SRI investing communities are shown in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3 International Specialist in Ethical and SRI

| Name | Role |

| Vigeo, Europe | The largest provider of Corporate Responsibility (CR) and SRI Research in Europe. |

| Bureau Veritas | The world leader in CR assurance services |

| Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI) | The international standard agency for CR reporting |

| United Nations Principles for Responsible Investment (UNPRI) | Terms of reference for CR investment |

Australian Ethical Investment Ltd., a publicly listed company in Australia Stock Exchange since 2002, is a pioneer in the ethical/SRI field. It is a success story of one of the longest established ethical fund managers. Operating with the sole purpose of ethical investment, the Canberra-based company commenced in 1986 and currently offers four public unit trusts.

For investors’ comfort, transparency is carried through by the company’s investment activities, guided by the Australian Ethical Charter.

BROADER PORTFOLIO DIVERSIFICATION

As an additional choice to bring Asian and Global SRI Investors into appreciating ethical portfolios quickly and at a low transaction cost, the OWW Responsibility SRI Asia Index Series allows investors to invest in passive management or index-tracking products. Investors can also seek fund houses that use this index series as a benchmark.

Just like Shariah-compliant investing, Active Asia Ethical Funds can be created as thematic funds, such as:

- Regional or country-specific Asia SRI Funds, covering all or specific sectors and firms

- Asia clean-tech funds, focusing on firms using or developing zero carbon emission technologies

- Asia Environment Funds, focusing on firms with environmental footprints and/or demonstrably good environmental performance

- Asia Good Governance Funds, focusing on firms with excellent and transparent corporate governance records and reporting practices

- Asia Human Rights Funds, focusing on firms that actively promote human rights in Asia

Like its Shariah counterpart, ethical investing covers broader portfolio diversification in vehicles—namely, mutual funds, structured products, feeder portfolio, commingled funds, managed accounts, institutional funds, discretionary portfolio, and subadvised portfolio.

CONCLUSION

For investors selecting an ethical manager, it is important to remember that one person’s ethics are not necessarily the same as another’s. However, in Shariah investing, the Shariah Advisory Panel of the Investment House determines what investments are Shariah compliant, which simplifies this decision from the investor’s perspective. A decision to invest in SRI or Shariah investment products will nevertheless depend on the investor’s own values as well as the investor’s overall portfolio and financial planning goals. For this reason, ethical and Shariah-compliant investors often seek fund managers offering a high level of disclosure and transparency in terms of investment process, portfolio listings, and detailed reporting.

Investing ethically or by following the Shariah way does not mean one has to sacrifice investment performance. As with any investment, some perform better than others. Ethical funds tend to hold a higher percentage of shares in small to medium-sized companies and a smaller percentage in larger companies than their nonethical equivalents.

High-profile accounting scandals at companies such as Enron (which was not in the Islamic index anyway, due to high leverage) have only added to the desire for corporations to focus not only on financial obligations but also on the social and environmental ones.

Shares in small companies can sometimes be more volatile than those of larger companies. For this reason, ethical funds are often perceived as being a riskier investment than their nonethical counterparts. Using this argument, the Shariah investing way will be more broad-based, with a larger market cap, thus granting more chances for stability and performance of the investor’s money compared to the “dark green” strict criteria of ethical funds.

Also, it is worth reminding investors that, for both ethical and Shariah investing, the investment tenor should be long term, 10 years or more, of which the net desired outcome will show that the performance of both ethical funds and Shariah funds are just as reliant on good management techniques as that of mainstream funds.

Indeed, there would seem potential for collaboration between Islamic and ethical managers and possibly room for multimanager funds that combine both approaches.

A matched-pair analysis between Islamic (Shariah compliant) and ethical funds demonstrated that they have similar performance abilities. The bottom line is that more and more investors adopt and use both ethical and Islamic investment strategies, not only because such investments allow a focus beyond the bottom line but also because returns of both are comparable to, if not better than, those from mainstream investments.

NOTES

1. Carol J. Loomis (2006, June 25). “Warren Buffett Gives Away His Fortune,” Fortune, http://money.cnn.com/2006/06/25/magazines/fortune/charity1.fortune/.

2. “Foundation Fact Sheet,” Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, www.gatesfoundation.org/about/Pages/foundation-fact-sheet.aspx.

3. Jorge Becerra, Peter Damisch, Bruce Holley, Monish Kumar, Matthias Naumann, Tjun Tang, and Anna Zakrzewski, “Global Wealth 2011: Shaping a New Tomorrow: How to Capitalize on the Momentum of Change,” BCG Perspectives (May 31, 2011): www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/financial_institutions_pricing_global_wealth_2011_shaping_new_tomorrow/.

4. Yusuf Talal DeLorenzo, “Shariah Screening” Muslim Investor (February 5, 2002).

5. www.djindexes.com/Islamicmarkets/

6. Talal DeLorenzo.

7. OWW Consulting, “Passive Management Options for SRI in Asia.” http://oww-consulting.com.my/sri/passive-management-options-asia

8. Direct Advisers, “Research.” www.directadvisers.com.au/Financial%20Planners%20Research.htm

9. Bloomberg LP, “Comparison between TKLD400U vs. FTWI01 and W1SGI vs. W1DOW,” December 31, 2007–December 31, 2012 (2012).

10. This verse, along with the legal maxim, explains that the investment should be streamlined in a way that realizes the wellbeing of the human through an ethical process of wealth accumulation and responsible investment. This is done by agreed-upon screening criteria, which realize the interest of the general public.

General Reading

Islamic Finance News supplements, “Islamic Investor: Equities vs. Commodities.” Red Money Publication, 2011.

Jaffer, Sohail, and Kamar Jaffer, Investing in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA Region): Fast Track Opportunities. Euromoney Institutional Investor Plc, 2012.

Jaffer, Sohail, Islamic Wealth Management: A Catalyst for Global Change and Innovation. Euromoney Books, 2009.

Landier, Augustin, and Vinay B. Nair, Investing for Change: Profit from Responsible Investment. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Lewis, Michael, The Money Culture. Hodder & Stoughton UK, 2011.