24 ASC 350 INTANGIBLES—GOODWILL AND OTHER

Amortization and impairment testing

Determining the fair value of a reporting unit

Recognition of impairment loss

Example of the goodwill impairment test

General Intangibles Other Than Goodwill (ASC 350-30)

Determining the useful of life of intangible assets

Amortization of intangible assets

Indefinite-Lived Intangible Assets

Quantitative impairment test for indefinite-lived intangible asset

Recognition of impairment loss for indefinite-lived intangible asset

Software Developed for Internal Use (ASC 350-40)

Costs subject to capitalization

Internal-use software subsequently marketed

Example of software developed for internal use

Website Development Costs (ASC350-50)

PERSPECTIVE AND ISSUES

Subtopics

ASC 350, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other, consists of five subtopics:

- ASC 350-10, Overall, which provides guidance for accounting and reporting on intangible assets

- ASC 350-20, Goodwill, which provides guidance on accounting for goodwill subsequent to acquisition and for the cost of internally developed goodwill

- ASC 350-30, General Intangibles Other Than Goodwill, which provides guidance on accounting and reporting for intangible assets other than goodwill acquired individually or with a group of other assets

- ASC 350-40, Internal-Use Software, which provides guidance on accounting for software developed for internal use and determining whether that software is for internal use

- ASC 350-50, Website Development Costs, which provides guidance on accounting for costs associated with the development of a website, including costs incurred:

– In the planning, application development, infrastructure development, and operating stages

– To develop graphics and content.

Scope exceptions

All of the subtopics above adopt the following scope limitations of ASC 350-10, the overall subtopic. The guidance does not apply to:

- Accounting at acquisition for goodwill acquired in a business combination (see ASC 805-30) or in an acquisition by a not-for-profit entity (see ASC 958-805).

- Accounting at acquisition for intangible assets other than goodwill acquired in a business combination or in an acquisition by a not-for-profit entity (see ASC 805-20 and ASC 958-805).

ASC 350-10-15-4 goes on to list locations that are not changed by the guidance in ASC 350:

- Research and development costs under Subtopic 730-10

- Extractive activities under Topic 932

- Entertainment and media, including records and music under Topic 928

- Financial services industry under Topic 950

- Entertainment and media, including broadcasters under Topic 920

- Regulatory operations under paragraphs 980-350-35-1 through 35-2

- Software under Topic 985

- Income taxes under Topic 740

- Transfers and servicing under Topic 860.

Issues

For manufacturing companies, the primary assets typically are tangible, such as buildings and equipment. For financial institutions, the major assets are financial instruments. For high-technology, knowledge-based companies, however, the primary assets are intangible, such as patents and copyrights, and for professional service firms the key assets may be “soft” resources, such as knowledge bases and client relationships. Overall, enterprises for which intangible assets constitute a large and growing component of total assets are a rapidly growing part of the economy, and there is pressure to improve the relevance of financial reporting in light of changing business and economic conditions.

Intangible assets are defined as both current and noncurrent assets that lack physical substance. Specifically excluded, however, are financial instruments and deferred income tax assets. The value of intangible assets is based on the rights or privileges to which they entitle the reporting entity. Most of the accounting issues associated with intangible assets involve their characteristics, valuation and amortization. Adequate consideration must be given to the economic substance of the transaction.

Note: For a summary and comparison of accounting and impairment rules for property, plant and equipment and intangibles, see the Perspectives and Issues section of the chapter on ASC 360.

Technical Alerts

In September 2011, the FASB issued ASU 2011-08, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Testing Goodwill for Impairment and amended the guidance on testing goodwill for impairment. The ASU was issued in response to concerns expressed by preparers about the cost and complexity of goodwill impairment testing. Testing for goodwill had been a two-step process. This update gives entities the option of performing a qualitative assessment before calculating the fair value in Step 1 of the impairment test. For more information, see the section in this chapter on impairment testing for goodwill.

In July 2012, the FASB issued ASU 2012-02, Intangibles—Goodwill and Other (Topic 350): Testing Indefinite-Lived Intangible Assets for Impairment. Intended to reduce costs, the ASU mirrors the guidance issued in 2011 for goodwill impairment testing. For more information, see the section in this chapter on impairment testing for indefinite-lived intangible assets.

DEFINITIONS OF TERMS

Source: ASC 350 Glossary sections

Acquiree. The business or businesses that the acquirer obtains control of in a business combination. This term also includes a nonprofit activity or business that a not-for-profit acquirer obtains control of in an acquisition by a not-for-profit entity.

Acquirer. The entity that obtains control of the acquire. However, in a business combination in which a variable interest entity (VIE) is acquired, the primary beneficiary of that entity always is the acquirer.

Acquisition by a non-for-profit entity. A transaction or other event in which a not-for-profit acquirer obtains control of one or more nonprofit activities or businesses and initially recognizes their assets and liabilities in the acquirer's financial statements. When applicable guidance in ASC 805 is applied by a not-for-profit entity, the term business combination has the same meaning as this term has for a not-for-profit entity. Likewise, a reference to business combinations in guidance that links to ASC 805 has the same meaning as a reference to acquisitions by not-for-profit entities.

Business. An integrated set of activities and assets that is capable of being conducted and managed for the purpose of providing a return in the form of dividends, lower costs, or other economic benefits directly to investors or other owners, members, or participants. Additional guidance on what a business consists of is presented in ASC 805-10-55-4 through 55-9.

Business combination. A transaction or other event in which an acquirer obtains control of one or more businesses. Transactions sometimes referred to as true mergers or mergers of equals also are business combinations. See also Acquisition by a not-for-profit entity.

Defensive intangible asset. An acquired intangible asset in a situation in which an entity does not intend to actively use the asset but intends to hold (lock up) the asset to prevent others from obtaining access to the asset.

Goodwill. An asset representing the future economic benefits arising from other assets acquired in a business combination or an acquisition by a not-for-profit entity that are not individually identified and separately recognized. For ease of reference, this term also includes the immediate charge recognized by not-for-profit entities in accordance with ASC 958-805-25-29.

Intangible asset class. A group of intangible assets that are similar, either by their nature or by their use in the operations of an entity.

Intangible assets. Assets (not including financial assets) that lack physical substance. (The term intangible assets is used to refer to intangible assets other than goodwill.)

Legal entity. Any legal structure used to conduct activities or to hold assets. Some examples of such structures are corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies, grantor trusts, and other trusts.

Mutual entity. An entity other than an investor-owned entity that provides dividends, lower costs, or other economic benefits directly and proportionately to its owners, members, or participants. Mutual insurance entities, credit unions, and farm and rural electric cooperatives are examples of mutual entities.

Nonprofit activity. An integrated set of activities and assets that is capable of being conducted and managed for the purpose of providing benefits, other than goods or services at a profit or profit equivalent, as a fulfillment of an entity's purpose or mission (for example, goods or services to beneficiaries, customers, or members). As with a not-for-profit entity, a nonprofit activity possesses characteristics that distinguish it from a business or a for-profit business entity.

Nonpublic entity. Any entity other than one with any of the following characteristics:

- Whose debt or equity securities trade in a public market either on a stock exchange (domestic or foreign) or in the over-the-counter market, including securities quoted only locally or regionally

- That is a conduit bond obligor for conduit debt securities that are traded in a public market (a domestic or foreign stock exchange or an over-the-counter market, including local or regional markets)

- That makes a filing with a regulatory agency in preparation for the sale of any class of debt or equity securities in a public market

- That is controlled by an entity covered by 1, 2, or 3.

Conduit debt securities refers to certain limited-obligation revenue bonds, certificates of participation, or similar debt instruments issued by a state or local governmental entity for the express purpose of providing financing for a specific third party (the conduit bond obligor) that is not a part of the state or local government's financial reporting entity. Although conduit debt securities bear the name of the governmental entity that issues them, the governmental entity often has no obligation for such debt beyond the resources provided by a lease or loan agreement with the third party on whose behalf the securities are issued. Further, the conduit bond obligor is responsible for any future financial reporting requirements.

Not-for-profit entity. An entity that possesses the following characteristics, in varying degrees, that distinguish it from a business entity:

- Contributions of significant amounts of resources from resource providers who do not expect commensurate or proportionate pecuniary return

- Operating purposes other than to provide goods or services at a profit

- Absence of ownership interests like those of business entities.

Entities that clearly fall outside this definition include the following:

- All investor-owned entities

- Entities that provide dividends, lower costs, or other economic benefits directly and proportionately to their owners, members, or participants, such as mutual insurance entities, credit unions, farm and rural electric cooperatives, and employee benefit plans.

Operating segment. A component of a public entity that has all of the following characteristics:

- It engages in business activities from which it may earn revenues and incur expenses,

- Its operating results are regularly reviewed by the public entity's chief operating decision maker to make decisions about resources to be allocated to the segment and assess its performance.

- Its discrete financial information is available.

Preliminary Project Stage. When a computer software project is in the preliminary project stage, entities will likely do the following:

- Make strategic decisions to allocate resources between alternative projects at a given point in time. For example, should programmers develop a new payroll system or direct their efforts toward correcting existing problems in an operating payroll system?

- Determine the performance requirements (that is, what it is that they need the software to do) and systems requirements for the computer software project it has proposed to undertake.

- Invite vendors to perform demonstrations of how their software will fulfill an entity's needs.

- Explore alternative means of achieving specified performance requirements. For example, should an entity make or buy the software? Should the software run on a mainframe or a client server system?

- Determine that the technology needed to achieve performance requirements exists.

- Select a vendor if an entity chooses to obtain software.

Public entity. A business entity or a not-for-profit entity that meets any of the following conditions:

- It has issued debt or equity securities or is a conduit bond obligor for conduit debt securities that are traded in a public market (a domestic or foreign stock exchange or an over-the-counter market, including local or regional markets).

- It is required to file financial statements with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

- It provides financial statements for the purpose of issuing any class of securities in a public market.

Reporting Unit. The level of reporting at which goodwill is tested for impairment. A reporting unit is an operating segment or one level below an operating segment (also known as a component).

Residual Value. The estimated fair value of an intangible asset at the end of its useful life to an entity, less any disposal costs.

Useful Life. The period over which an asset is expected to contribute directly or indirectly to future cash flows.

Variable interest entity. A legal entity subject to consolidation according to the provisions of the Variable Interest Entities Subsections of Subtopic 810-10.

CONCEPTS, RULES, AND EXAMPLES

Goodwill (ASC 350-20)

Goodwill is not considered an identifiable intangible asset, and accordingly, under ASC 350-20, it is accounted for differently from identifiable intangibles. The lack of identifiability is the critical element in the definition of goodwill. Accordingly, identifiable intangible assets that are reliably measurable are recognized and reported separately from goodwill.

Costs of internally developed goodwill are expensed as incurred (ASC 350-20-25-3) Accounting at acquisition for goodwill acquired during the acquisition of an entire entity is accounted for under the provisions of ASC 805-30. Accounting at acquisition for goodwill acquired at acquisition by a not-for-profit entity is accounted for under the provisions of 958-805.

Amortization and impairment testing.

Goodwill is considered to have an indefinite life and, therefore, is not amortized. Goodwill is, however, subject to unique impairment testing techniques. Goodwill is impaired when its implied fair value is less than its carrying amount. The fair value of goodwill cannot be measured directly; it can only be “implied,” that is, measured as a residual.

Reporting unit. The impairment test for goodwill is performed at the level of the reporting unit. A reporting unit, as detailed in ASC 350-20-35-33 through 46, is an operating segment or one level below an operating segment. In the chapter on ASC 280, the diagram entitled “Alternative Balance Sheet Segmentation” illustrates how different groupings in a business can be characterized as reporting units. The diagram is accompanied by definitions of reporting units, operating segments, and other organizational groupings. The reporting entity may internally refer to reporting units by terms such as business units, operating units, or divisions.

Determination of reporting units is largely dependent on how the business is managed and its structure for reporting and management accountability. An entity may have only one reporting unit, which would, of course, result in the goodwill impairment test being performed at the entity level. This can occur when the entity has acquired a business that it has integrated with its existing business in such a manner that the acquired business is not separately distinguishable as a reporting unit.

On the date an asset is acquired or a liability is assumed, the asset or liability is assigned to a reporting unit if it meets both of the following conditions:

- The asset will be used in or the liability is related to the operations of a reporting unit

- The asset or liability will be considered in determining the fair value of the reporting unit.

The methodology used to determine reporting units must be reasonable and supportable and must be applied similarly to how aggregate goodwill is determined in a purchase business combination.

Net assets include assets and liabilities that are recognized as “corporate” items if they, in fact, relate to the operations of the reporting unit. Examples of corporate items are environmental liabilities associated with land owned by a reporting unit, and pension assets and liabilities attributable to employees of a reporting unit. Executory contracts (e.g., operating leases, contracts for purchase or sale, construction contracts) are considered part of net assets only if the amount reflected in the acquirer's financial statements is based on a fair value measurement subsequent to entering into the contract. To illustrate, if an acquiree had a preexisting operating lease on either favorable or unfavorable terms as compared to its fair value on the date of acquisition, the acquirer would recognize, in its purchase price allocations, an asset or liability for the fair value of the favorable or unfavorable terms, respectively. ASC 350 distinguishes between accounting for this fair value of an otherwise unrecognized executory contract and prepaid rent or rent payable, which generally have carrying values that approximate their fair values.

Implied fair value. The implied fair value of goodwill is the excess of the fair value of the reporting unit as a whole over the fair values that would be assigned to its assets and liabilities in a purchase business combination.

Timing of testing. The annual goodwill impairment test may be performed at any time during the fiscal year as long as it is done consistently at the same time each year.

Each reporting unit is permitted to establish its own annual testing date. ASC 350-20-35-30 indicates that additional impairment tests are required between annual impairment tests if:

- They are warranted by a change in events and circumstances, and

- It is more likely than not that the fair value of the reporting unit is below its carrying amount.

ASC 350-20-35-30 references ASC 350-20-35-3C to provide examples of events or circumstances that require goodwill of a reporting unit to be tested for impairment between annual tests.

- Macroeconomic conditions, such as a deterioration in general economic conditions, limitations on accessing capital, fluctuations in foreign exchange rates, or other developments in equity and credit markets

- Industry and market considerations, such as a deterioration in the environment in which city an entity operates, an increased competitive environment, a decline in market-dependent multiples or metrics (consider in both absolute terms and relative to peers), a change in the market for entity's products or services, or a regulatory or political development

- Cost factors, such as increases in raw materials, labor, or other costs that have a negative effect on earnings and cash flows

- Overall financial performance, such as negative or declining cash flows or a decline in actual or planned revenue or earnings compared with actual and projected results of relevant prior periods

- Other relevant entity-specific events, such as changes in management, key personnel, strategy, or customers; contemplation of bankruptcy; or litigation

- Events affecting a reporting unit, such as a change in the composition or carrying amount of its net assets, a more-likely-than-not expectation of selling or disposing all, or a potion, of a reporting unit, or recognition of a goodwill impairment loss in the financial statements of a subsidiary that is a component of a reporting unit

- If applicable, a sustained decrease in share price (consider in both absolute terms and relative to peers).

This list is not intended to be all-inclusive. Other indicators may come to the attention of management that would indicate that goodwill impairment testing should be performed between annual tests. Goodwill must also be tested for impairment if a portion of goodwill is allocated to a business to be disposed of.

If indicators exist requiring impairment testing of goodwill, impairment testing of nonamortizable intangibles, and/or recoverability evaluation of tangible long-lived assets or amortizable intangibles, the other assets are tested/evaluated first and any impairment loss is recognized prior to testing goodwill for impairment.

Performing the impairment test. In September 2011, the FASB issued ASU 2011-08 and amended the guidance on testing goodwill for impairment. To what had been a two-step process, the FASB has, in effect, introduced “Step 0.” Step 0 gives entities the option of performing a qualitative assessment before calculating the fair value in Step 1. In the qualitative assessment, entities determine whether it is more likely than not that the fair value of the reporting unit is less than the carrying amount. The qualitative assessment is optional and entities may bypass it for any reporting unit in any period.

The factors listed previously that indicate impairment testing should be done between annual tests are the same as those that should be considered in the qualitative assessment. (See ASC 350-20-35-3C examples above.)

ASC 350-20-35-3F goes on to say that these examples are not all-inclusive, and offers other events and circumstances than an entity must consider:

An entity shall consider the extent to which each of the adverse events and circumstances identified could affect the comparison of a reporting unit's fair value with its carrying amount. An entity should place more weight on the events and circumstances that most affect a reporting unit's fair value or the carrying amount of its net assets. An entity also should consider positive and mitigating events and circumstances that may affect its determination of whether it is more likely than not that the fair value of a reporting unit is less than its carrying amount. If an entity has a recent fair value calculation for reporting unit, it also should include as a factor in its consideration the difference between the fair value and the carrying amount in reaching its conclusion about whether to perform the first step of the goodwill impairment test.

ASC 350-20-35-3G advises that the events and circumstances should be considered in context and no one event necessarily requires the entity to perform Step 1.

If it is not more likely than not that the fair value of the reporting unit is less than the carrying amount, further testing is not performed. If it is more likely than not the fair value of the reporting unit is less than the carrying amount, the entity proceeds to Step 1.

Step 1. Compare the fair value of the reporting unit as a whole to its carrying value, including goodwill.

- If the reporting unit's carrying amount is greater than zero and its fair value exceeds its carrying value, goodwill is not impaired and no further computations are required.

- If the reporting unit has a zero or negative carrying amount, then the entity must proceed to the next step if it is more likely than not that a goodwill impairment exists. In making this evaluation, the entity should consider whether there are significant differences between the carrying amount and the estimated fair value of the assets and liabilities, and the existence of significant unrecognized intangible assets. (ASC 350-20-35-8)

- If the carrying value of the reporting unit exceeds its fair value, the second step of the impairment test is required.

Step 2. Determine whether and by how much goodwill is impaired as follows:

- Estimate the implied fair value of goodwill.

- Compare the implied fair value of goodwill to its carrying amount.

- If the carrying amount of goodwill exceeds its implied fair value, it is impaired and is written down to the implied fair value.

Consistent with long-standing practice in GAAP, upon recognition of an impairment loss, the adjusted carrying amount of goodwill becomes its new cost basis, and future restoration of the written down amount is prohibited.

Determining the implied fair value of goodwill. The fair value of a reporting unit is defined in the ASC 350 Glossary as the price that would be received to sell the unit as a whole in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date. The determination of the implied fair value of goodwill is based on the assumption that the fair value of a reporting unit as a whole differs from the fair value of its identifiable net assets. This is the general principle that gives rise to goodwill in the first place. The acquirer assigns additional value to the acquiree (as evidenced by a purchase price that exceeds the collective fair values of the assets and liabilities to be acquired) based on the acquirer's perceived ability to take advantage of synergies and other benefits that flow from its control over the acquiree.

Determining the fair value of a reporting unit.

Quoted market prices in active markets are considered the best evidence of fair value and are to be used if available. However, market capitalization of a publicly traded business unit is computed based on a quoted market price per share that does not consider any advantages that might inure to an acquirer in a situation where control is obtained. For this reason, ASC 350-20-35-23 cautions that the market capitalization of a reporting unit with publicly traded stock may not be representative of its fair value. Presumably, estimating the fair value of a privately held business using earnings multiples derived from publicly traded companies in the same line of business might have the same limitation.

ASC 350 also prescribes that when a significant portion of a reporting unit is comprised of an acquired entity, the same techniques and assumptions used to determine the purchase price of the acquisition are to be used to measure the fair value of the reporting unit unless such techniques and assumptions are not consistent with the objective of measuring fair value.

If quoted market prices are not available, the estimate of fair value is to be based on the best information available, including prices for similar assets and liabilities or the results of applying available valuation techniques. Such techniques include expected present value methods, option pricing models, matrix pricing, option-adjusted spread models, and fundamental analysis. The weight given to evidence gathered in the valuation process must be proportional to the ability to objectively observe it. When an estimate is in the form of a range of either the amount or timing of estimated future cash flows, the likelihood of possible outcomes should be considered (i.e., probability weightings are assigned in order to estimate the most likely outcome).

The measurement techniques and assumptions used to estimate the fair values of the reporting unit's net assets should be consistent with those used to measure the fair value of the reporting unit as a whole. For example, estimates of the amounts and timing of cash flows used to value the significant assets of the reporting unit are to be consistent with those assumptions used to estimate such cash flows at the reporting unit level when a cash flow model is used to estimate the reporting unit's fair value as a whole.

For the purposes of determining the fair value of a reporting unit, the relevant facts and circumstances are to be carefully evaluated with respect to whether to assume that the reporting unit could be bought or sold in a taxable or nontaxable transaction. The factors to consider in making the evaluation are set forth in ASC 350-20-35.

- The assumptions that marketplace participants would make in estimating fair value

- The feasibility of the assumed structure considering

- The ability to sell the reporting unit in a nontaxable transaction, and

- Any limits on the entity's ability to treat a sale as a nontaxable transaction imposed by income tax laws or regulations, or corporate governance requirements.

- Whether the assumed structure would yield the best economic after-tax return to the (hypothetical) seller for the reporting unit.

If a reporting unit is not wholly owned by the reporting entity, the fair value of that reporting unit and the implied fair value of goodwill are to be determined in the same manner as prescribed by ASC 805. If the reporting unit includes goodwill that is solely attributable to the parent, any impairment loss would be attributed entirely to the parent. If, however, the reporting unit's goodwill is attributable to both the parent and the noncontrolling interest, the impairment loss would need to be allocated to both the parent and the noncontrolling interest in a rational manner. The same logic applies to gain or loss on disposal of all or a portion of a reporting unit. When that reporting unit is disposed of, the gain or loss on disposal is to be attributed to both the parent and to the noncontrolling interest.

For the purpose of goodwill impairment testing, the carrying value of a reporting unit includes deferred income taxes irrespective of whether fair value of the reporting unit was determined assuming taxable or nontaxable treatment.

Measuring Fair Value.

Implied Fair Value Computation. For the purpose of computing the implied fair value of reporting unit goodwill, assumptions must be made as to the income tax bases of the reporting unit's assets and liabilities in order to compute any relevant deferred income taxes. If the computation of the reporting unit's fair value in Step 1 of the goodwill impairment test assumed that the reporting unit was structured as a taxable transaction, then new income tax bases are used. Otherwise the existing income tax bases are used (ASC 350-20-35).

Recognition of impairment loss.

If the carrying amount of the reporting unit's good will exceeds the implied fair value of that goodwill, an impairment loss in the amount equal to the excess is recognized. The recognized loss cannot exceed the carrying amount of goodwill. The new carrying amount of the goodwill is the adjusted amount after recognizing the loss. Once the loss is recognized, it cannot be reversed subsequently.

If the second step of the impairment test is not completed before the financial statements are issued and a loss is probable, the entity should recognized the loss and disclose the fact that it is an estimate. Upon completion of the test, the entity may make an adjustment to that estimated loss in the subsequent period.

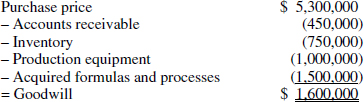

Spectral Corporation acquires FarSite Binocular Company for $5,300,000; of this amount, $3,700,000 is assigned to a variety of assets, with the remaining $1,600,000 assigned to goodwill, as noted in the following table:

The asset allocation related to acquired formulas and processes is especially critical to the operation, since it refers to the use of a proprietary lens coating system that allows FarSite's binoculars to yield exceptional clarity in low-light conditions. This asset is being depreciated over ten years.

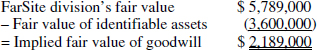

One year after the acquisition date, the FarSite division has recorded annual cash flow of $1,450,000; assuming the same cash flow for the next five years, the present value of the expected cash flows, discounted at the corporate cost of capital of 8%, is roughly $5,789,000. Also, an independent appraisal firm assigns a fair value of $3,600,000 to FarSite's identifiable assets. With this information, the impairment test follows:

Though the implied fair value of FarSite's goodwill has increased, Spectral's controller cannot record this increase.

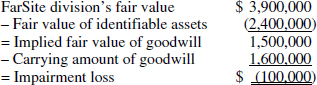

A few months later, Spectral's management learns that a Czech optics company has created a competing optics coating process that is superior to and less expensive than FarSite's process. Since this will likely result in a reduction in FarSite's fair value below its carrying amount, Spectral conducts another impairment test. Management assumes that the forthcoming increase in competition will reduce the expected present value of its cash flows to $3,900,000. In addition, the appraisal firm now reduces its valuation of the acquired formulas and processes asset by $1,200,000. The revised impairment test follows:

Since the implied fair value of goodwill is $100,000 less than its current carrying amount, Spectral's controller uses the following entry to record reduction in value:

![]()

In addition, Spectral's controller writes down the value of the acquired formulas and processes by the amount recommended by the appraisal firm with the following entry:

![]()

A year later, FarSite's research staff discovers an enhancement to its optical coating process that will restore FarSite's competitive position against the Czech firm. However, Spectral's controller cannot increase the carrying cost of the acquired formulas and processes or goodwill to match their newly increased fair value and implied fair value, respectively.

Other goodwill considerations.

Other provisions included in ASC 350 include the following:

- Equity method goodwill continues to be recognized under ASC 323 and is not subject to amortization. This goodwill is not tested for impairment under ASC 350, but rather, is tested under ASC 323. This test considers whether the fair value of the underlying investment has declined and whether that decline is “other than temporary.”

- Goodwill of a reporting unit that is fully disposed of is included in the carrying amount of the net assets disposed of in computing the gain or loss on disposal.

- If a significant portion of a reporting unit is disposed of, the goodwill of that unit is required to be tested for impairment. In performing the impairment test, only the net assets to be retained after the disposal are included in the computation. If, as a result of the test, the carrying amount of goodwill exceeds its implied fair value, the excess carrying amount is allocated to the carrying amount of the net assets disposed of in computing the gain or loss on disposal and, consequently, is not considered an impairment loss.

Presentation.

To provide financial statement users with transparent information about goodwill, ASC 350-20-45 requires separate line item treatment as follows:

- Balance sheet (statement of financial position)—the aggregate amount of goodwill included in assets is captioned separately from other assets and may not be combined with other intangibles.

- Income statement—the aggregate amount of goodwill impairment losses is captioned separately in the operating section unless associated with discontinued operation.

If the goodwill impairment loss is associated with a discontinued operation, the loss should be presented net of tax within discontinued operations.

General Intangibles Other Than Goodwill (ASC 350-30)

Intangible assets, other than goodwill, fall into two categories:

- Those with finite useful lives, which are amortized and subject to impairment testing

- Those with indefinite lives, which are not amortized, but are subject to impairment testing.

Initial recognition of intangible assets. Intangibles acquired individually or with a group of other assets1 are initially recognized and measured based on their fair values. Fair value, consistent with ASC 820 Fair Value, is determined based on the assumptions that market participants would use in pricing the asset. Even if the reporting entity does not intend to use an intangible asset in a manner that is its highest and best use, the intangible is nevertheless measured at its fair value.

Per 805-20-S99-3, the SEC does not allow an entity to assign a purchase price, rather than fair value, to intangible assets, and then allocate the remainder of the acquisition price to an “indistinguishable” intangible asset.

The aggregate amount assigned to a group of assets acquired in other than a business combination is to be allocated to the individual assets acquired based on their relative fair values. Goodwill is prohibited from being recognized in such an asset acquisition (ASC 350-30-25-2).

Although a reporting entity can purchase intangibles that were developed by others, US GAAP continues to maintain a strict prohibition against capitalizing costs of internally developing, maintaining, or restoring intangibles, including goodwill (ASC 350-30-25-3). Exceptions to this general rule are software developed for internal use and Website development costs. Both are discussed later in this chapter.

Determining the useful of life of intangible assets.

An income approach is commonly used to measure the fair value of an intangible asset. The period of expected cash flows used to measure fair value of the intangible, adjusted for applicable entity-specific factors, is to be considered by management in determining the useful life of the intangible for amortization purposes.

Under ASC 350-30-35-3, in estimating the useful life of an intangible asset, the reporting entity is to consider:

- The entity's expected use of the asset

- The expected useful life of another asset or asset group to which the useful life of the intangible asset may be related

- Any provisions contained in applicable law, regulation, or contract that may limit the useful life

- The entity's own historical experience in renewing or extending similar arrangements if such experience is consistent with the intended use of the intangible asset by the reporting entity, irrespective of whether those similar arrangements contained explicit renewal or extension provisions. In the absence of such historical experience, management is to consider the assumptions that market participants would use about the renewal or extension consistent with their highest and best use of the asset, and adjusted for relevant entity-specific factors.

- The effects of obsolescence, demand, competition, and other economic factors such as

- Stability of the industry,

- Known technological advances,

- Legislative action that results in an uncertain or changing regulatory environment, and

- Expected changes in distribution channels.

- The level of maintenance expenditures that would be required to obtain the expected future cash flows from the asset.

If no legal, regulatory, contractual, competitive, economic, or other factors limit the useful life of an intangible asset to the reporting entity, the useful life of the asset is considered to be indefinite (which, of course, is not the same as unlimited or infinite). (ASC 350-30-35-4)

Defensive intangible assets. In connection with a business combination or asset acquisition, management of the acquirer may acquire intangible assets that it does not intend to actively use but, rather, wishes to hold in order to prevent other parties from employing them or obtaining access to them. As noted in ASC 350-30-25-5, these intangibles are often referred to as defensive assets, or as “locked-up assets.”2

To qualify as a defensive intangible asset, the asset must be either

- Acquired with the intent to not use it or

- Used by the acquirer with the intent to discontinue its use after completion of a transition period.

(ASC 350-30-55-1)

Obviously, upon being characterized as a defensive intangible, the asset is precluded from being considered abandoned upon acquisition, regardless of the fact that it is not being used.

Subsequent to the asset being characterized as a defensive intangible, management may decide to actively employ the asset. If so, it would cease to be considered a defensive intangible. (ASC 350-30-55-1B)

At acquisition, defensive intangibles are subject to the same fair value valuation principles as any other acquired intangible asset, including that they be measured considering exit price to marketplace participants that would put them to their highest and best use. In making the measurement, defensive intangibles are accounted for as a separate unit of accounting and are not to be grouped with other intangibles.

It would be rare for defensive intangible assets to have an indefinite life, since lack of market exposure and competitive and other factors contribute to diminish the fair value of these assets over time (AsC 350-30-35-5B).

Defensive intangible assets are, in theory, to be assigned a useful life representing how (and for how long) the entity expects to consume the expected benefits related to them in the form of direct and indirect cash flows that would result from the prevention of others from realizing any value from them. In practice, however, such estimates would be difficult to make and highly subjective; consequently, ASC 350-30-35-5A substituted what it believed to be a more workable determination of useful life based on management's estimate of the period over which the defensive intangible asset diminishes in fair value.

Amortization of intangible assets.

Identifiable intangible assets, such as franchise rights, customer lists, trademarks, patents and copyrights, and licenses are to be amortized over their expected useful economic life with required impairment reviews of their recoverability when necessitated by changes in facts and circumstances in the same manner as set forth in ASC 360 for tangible long-lived assets.

ASC 350-30-35-8 also requires consideration of the intangible's residual value (analogous to salvage value for a tangible asset) in determining the amount of the intangible to amortize. Residual value is defined as the value of the intangible to the entity at the end of its (entity-specific) useful life reduced by any estimated disposition costs. The residual value of an amortizable intangible is assumed to be zero unless the intangible will continue to have a useful life to another party after the end of its useful life to its current holder, and one or both of the following criteria are met:

- The current holder has received a third-party commitment to purchase the intangible at the end of its useful life, or

- A market for the intangible exists and is expected to continue to exist at the end of the asset's useful life as a means of determining the residual value of the intangible by reference to marketplace transactions.

The entity should evaluate the residual value each reporting period.

Amortization and impairment considerations. Many intangible assets are based on rights that are conveyed legally by contract, statute, or similar means. For example, governments grant franchises or similar rights to taxi companies, cable companies, and hydroelectric plants; and companies and other private-sector organizations grant franchises to automobile dealers, fast-food outlets, and professional sports teams. Other rights, such as airport landing rights, are granted by contract. Some of those franchises or similar rights are for finite terms, while others are perpetual. Many of those with finite terms are routinely renewed, absent violations of the terms of the agreement, and the costs incurred for renewal are minimal. Many such assets are also transferable, and the prices at which they trade reflect expectations of renewal at minimal cost. However, for others, renewal is not assured, and their renewal may entail substantial cost.

Trademarks, service marks, and trade names may be registered with the government for a period of twenty years and are renewable for additional twenty-year periods as long as the trademark, service mark, or trade name is used continuously. (Brand names, often used synonymously with trademarks, are typically not registered and thus the required attribute of control will be absent.) The US government now grants copyrights for the life of the creator plus fifty years. Patents are granted by the government for a period of seventeen years but may be effectively renewed by adding minor modifications that are patented for additional seventeen-year periods. Such assets also are commonly transferable.

A broadcast license, while nominally subject to expiration in five years, might be indefinitely renewable at little additional cost to the broadcaster. If cash flows can be projected indefinitely, and assuming a market exists for the license, no amortization is to be recorded until such time as a finite life is predicted. However, impairment is required to be tested at least annually to ensure that the asset is carried at no more than its fair value. (ASC 350-30-55-12)

The foregoing examples all addressed identifiable intangibles, which are recognized in the financial statements when purchased separately or in connection with a business combination. There are other intangibles, which are deemed to not be identifiable because they cannot be reliably measured. Technological know-how and an assembled workforce are examples of such intangible assets. Intangibles that cannot be separately identified are considered integral components of goodwill.

Indefinite-Lived Intangible Assets.

Identifiable intangible assets having indefinite useful economic lives supported by clearly identifiable cash flows are not subject to regular periodic amortization. Instead, the carrying amount of the intangible is tested for impairment annually, and again between annual tests if events or circumstances warrant such a test. An impairment loss is recognized if the carrying amount exceeds the fair value. Furthermore, amortization of the asset commences when evidence suggests that its useful economic life is no longer deemed indefinite.

Testing for Impairment of Indefinite-Lived Intangible Assets. In July 2012, the FASB issued Accounting Standards Update No. 2012-02, Testing Indefinite-Lived Intangible Assets for Impairment. Intended to reduce costs, the ASU mirrors the guidance issued in 2011 for goodwill impairment testing. The standard gives the entity the option to first assess qualitatively whether it is more likely than not (more than 50 percent) that the asset is impaired. The qualitative assessment test can be performed on some or all of the assets, or the entity can bypass the qualitative test and perform the quantitative test.

If it is not more likely than not that the asset is impaired, the entity does not have to calculate the fair value of the intangible asset and perform the quantitative impairment test. If it is more likely than not that the asset is impaired, the entity must perform the quantitative impairment test and calculate the fair value of an indefinite-lived intangible asset.

ASU 2012-02 is effective for annual and interim impairment tests performed for fiscal years beginning after September 15, 2012. An entity can choose to early adopt the revised guidance even if its annual test date is before the issuance of the revised standard, provided that the entity has not yet performed its 2012 annual impairment test or issued its financial statements.

If performing the qualitative assessment, the entity needs to identify and consider those events and circumstances that, individually or in the aggregate, most significantly affect an indefinite-lived intangible asset's fair value. Examples of events and circumstances that should be considered include those listed in ASC 350-30-35-18B:

- Cost factors such as increases in raw materials, labor, or other costs that have a negative effect on future expected earnings and cash flows that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset

- Financial performance such as negative or declining cash flows or a decline in actual or planned revenue or earnings compared with actual and projected results of relevant prior periods that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset

- Legal, regulatory, contractual, political, business, or other factors, including asset-specific factors that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset

- Other relevant entity-specific events such as changes in management, key personnel, strategy, or customers; contemplation of bankruptcy; or litigation that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset

- Industry and market considerations such as a deterioration in the environment in which an entity operates, an increased competitive environment, a decline in market-dependent multiples or metrics (in both absolute terms and relative to peers), or a change in the market for an entity's products or services due to the effects of obsolescence, demand, competition, or other economic factors (such as the stability of the industry, known technological advances, legislative action that results in an uncertain or changing business environment, and expected changes in distribution channels) that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset

- Macroeconomic conditions such as deterioration in general economic conditions, limitations on accessing capital, fluctuations in foreign exchange rates, or other developments in equity and credit markets that could affect significant inputs used to determine the fair value of the indefinite-lived intangible asset.

Any positive and mitigating events and circumstances should also be considered, as well as the difference between the fair value in a recent calculation of an indefinite-lived intangible asset and the then carrying amount, whether there have been changes to the carrying amount of the indefinite-lived intangible asset (ASC 350-30-35-18C).

Determining the unit of accounting. ASC 350-30-35 provides guidance about when it is appropriate to combine into a single “unit of accounting” for impairment testing purposes, separately recorded indefinite-life intangibles, whether acquired or internally developed.

The assets may be combined into a single unit of accounting for impairment testing if they are operated as a single asset and, as such, are inseparable from one another. The following indicators are to be used in evaluating the individual facts and circumstances to enable the exercise of judgment (ASC 350-30-35-21).

Indicators that indefinite-lived intangibles are to be combined as a single unit of accounting. (ASC 350-30-35-23)

- The intangibles will be used together to construct or enhance a single asset.

- If the intangibles had been part of the same acquisition, they would have been recorded as a single asset.

- The intangibles, as a group, represent “the highest and best use of the assets” (e.g., they could probably realize a higher sales price if sold together than if they were sold separately). Indicators pointing to this situation are:

- The unlikelihood that a substantial portion of the assets would be sold separately, or

- The fact that, should a substantial portion of the intangibles be sold individually, there would be a significant reduction in the fair value of the remaining assets in the group.

- The marketing or branding strategy of the entity treats the assets as being complementary (e.g., a trademark and its related trade name, formulas, recipes, and patented or unpatented technology can all be complementary to an entity's brand name).

Indicators that indefinite-lived intangibles are not to be combined as a single unit of accounting. (ASC 350-30-35-24)

- Each separate intangible generates independent cash flows.

- In a sale, it would be likely that the intangibles would be sold separately. If the entity had previously sold similar assets separately, this would constitute evidence that combining the assets would not be appropriate.

- The entity is either considering or has already adopted a plan to dispose of one or more of the intangibles separately.

- The intangibles are used exclusively by different asset groups (as defined in the ASC Master Glossary).

- The intangibles have differing useful economic lives.

ASC 350-30-35-26 provides guidance regarding the “unit of accounting” determination.

- Goodwill and finite-lived intangibles are not permitted to be combined in the “unit of accounting” since they are subject to different impairment rules.

- If the intangibles collectively constitute a business, they may not be combined into a unit of accounting.

- If the unit of accounting includes intangibles recorded in the separate financial statements of consolidated subsidiaries, it is possible that the sum of impairment losses recognized in the separate financial statements of the subsidiaries will not equal the consolidated impairment loss.

NOTE: Although counterintuitive, this situation can occur when:

- At the separate subsidiary level, an intangible asset is impaired since the cash flows from the other intangibles included in the unit of accounting that reside in other subsidiaries cannot be considered in determining impairment, and

- At the consolidated level, when the intangibles are considered as a single unit of accounting, they are not impaired.

- Should a unit of accounting be included in a single reporting unit, that same unit of accounting and associated fair value is to be used in computing the implied fair value of goodwill for measuring any goodwill impairment loss.

Quantitative impairment test for indefinite-lived intangible asset.

This test consists simply of comparing the fair value of the asset with its carrying amount.

Recognition of impairment loss for indefinite-lived intangible asset.

If the carrying amount exceeds its fair value, the entity recognizes an impairment loss equal to that excess. After recognition of the loss, the adjusted carrying amount becomes the new basis for that intangible asset.

Presentation.

To provide financial statement users with transparent information about intangible assets, ASC 350-30-45 requires:

- Statement of Financial Position: All intangible assets must be aggregated and presented as a separate line item in the statement of financial position. The entity may also choose to present individual intangible assets or classes of intangible assets as separate line items.

- Income Statement: As appropriate, the entity should present amortization expense and impairment losses in line items within continuing operations.

Software Developed for Internal Use (ASC 350-40)

ASC 350-40-05-02 and 03 provide guidance on accounting for the costs of software developed for internal use. Software must meet two criteria to be accounted for as internal-use software:

- The software's specifications must be designed or modified to meet the reporting entity's internal needs, including costs to customize purchased software.

- During the period in which the software is being developed, there can be no plan or intent to market the software externally, although development of the software can be jointly funded by several entities that each plan to use the software internally.

To justify capitalization of related costs, it is necessary for management to conclude that it is probable that the project will be completed and that the software will be used as intended. Absent that level of expectation, costs must be expensed currently as research and development costs. Entities that engage in both research and development of software for internal use and for sale to others must carefully identify costs with one or the other activity, since the former is (if all conditions are met) subject to capitalization, while the latter is expensed as research and development costs until technological feasibility is demonstrated, per ASC 985-20.

Costs subject to capitalization.

Cost capitalization commences when an entity has completed the conceptual formulation, design, and testing of possible project alternatives, including the process of vendor selection for purchased software, if any. These early-phase costs (referred to as “preliminary project stage” in ASC 350-40) are analogous to research and development costs and must be expensed as incurred. These cannot be later restored as assets if the development proves to be successful.

Costs incurred subsequent to the preliminary project stage that meet the criteria under GAAP as long-lived assets are capitalized and amortized over the asset's expected economic life. Capitalization of costs begins when both of two conditions in ASC 350-40-25-12 are met.

- First, management having the relevant authority authorizes and commits to funding the project and believes that it is probable that it will be completed and that the resulting software will be used as intended.

- Second, the conceptual formulation, design, and testing of possible software project alternatives (i.e., the preliminary project stage) have all been completed.

Application development stage. Costs capitalized include those of the application development stage of the software development process. These include coding and testing activities and various implementation costs. ASC 350-40-30-1 limits these costs to:

- External direct costs of materials and services consumed in developing or obtaining internal-use computer software;

- Payroll and payroll-related costs for employees who are directly associated with and who devote time to the internal-use computer software project to the extent of the time spent directly on the project; and

- Interest cost incurred while developing internal-use computer software, consistent with the provisions of ASC 835-20.

Costs expensed. General and administrative costs, overhead costs, and training costs are expensed as incurred (ASC 350-40-30-3). Even though these may be costs associated with the internal development or acquisition of software for internal use, under GAAP those costs relate to the period in which they are incurred. The issue of training costs is particularly important, since internal-use computer software purchased from third parties often includes, as part of the purchase price, training for the software (and often fees for routine maintenance as well). When the amount of training or maintenance fees is not specified in the contract, entities are required to allocate the cost among training, maintenance, and amounts representing the capitalizable cost of computer software. Training costs are recognized as expense as incurred. Maintenance fees are recognized as expense ratably over the maintenance period.

Examples of computer software developed for internal use. ASC 350-40-55-1 provides examples of when computer software is acquired or developed for internal use. The following is a list of examples illustrating when computer software is for internal use:

- A manufacturing entity purchases robots and customizes the software that the robots use to function. The robots are used in a manufacturing process that results in finished goods.

- An entity develops software that helps it improve its cash management, which may allow the entity to earn more revenue.

- An entity purchases or develops software to process payroll, accounts payable, and accounts receivable.

- An entity purchases software related to the installation of an online system used to keep membership data.

- A travel agency purchases a software system to price vacation packages and obtain airfares.

- A bank develops software that allows a customer to withdraw cash, inquire about balances, make loan payments, and execute wire transfers.

- A mortgage loan servicing entity develops or purchases computer software to enhance the speed of services provided to customers.

- A telecommunications entity develops software to run its switches that are necessary for various telephone services such as voice mail and call forwarding.

- An entity is in the process of developing the accounts receivable system. The software specifications meet the entity's internal needs and the entity did not have a marketing plan before or during the development of the software. In addition, the entity has not sold any of its internal-use software in the past. Two years after completion of the project, the entity decided to market the product to recoup some or all of its costs.

- A broker-dealer entity develops a software database and charges for financial information distributed through the database.

- An entity develops software to be used to create components of music videos (for example, the software used to blend and change the faces of models in music videos). The entity then sells the final music videos, which do not contain the software, to another entity.

- An entity purchases software to computerize a manual catalog and then sells the manual catalog to the public.

- A law firm develops an intranet research tool that allows firm members to locate and search the firm's databases for information relevant to their cases. The system provides users with the ability to print cases, search for related topics, and annotate their personal copies of the database.

(ASC 350-40-55-1)

On the other hand, software that does not qualify as being for internal use includes software sold by a robot manufacturer to purchasers of its products; the cost of developing programs for microchips used in automobile electronic systems; software developed for both sale to customers and internal use; computer programs written for use in research and development efforts; and costs of developing software under contract with another entity. ASC 350-40-55-2 contains more examples.

Impairment.

Impairment of capitalized internal-use software is recognized and measured in accordance with the provisions of ASC 360 in the same manner as tangible long-lived assets and other amortizable intangible assets. Per ASC 350-40-35-1, circumstances that might suggest that an impairment has occurred and that would trigger a recoverability evaluation include

- A realization that the internal-use computer software is not expected to provide substantive service potential;

- A significant change in the extent or manner in which the software is used;

- A significant change has been made or is being anticipated to the software program; or

- The costs of developing or modifying the internal-use computer software significantly exceed the amount originally expected. These conditions are analogous to those generically set forth by ASC 360, Property, Plant, and Equipment.

In some instances, ongoing software development projects will become troubled before being discontinued. ASC 350-40 indicates that management needs to assess the likelihood of successful completion of projects in progress. When it becomes no longer probable that the computer software being developed will be completed and placed in service, the asset is to be written down to the lower of the carrying amount or fair value, if any, less costs to sell. Importantly, it is a rebuttable presumption that any uncompleted software has a zero fair value.

ASC 350-40-35-3 provides indicators that the software is no longer expected to be completed and placed in service. These include

- A lack of expenditures budgeted or incurred for the project;

- Programming difficulties that cannot be resolved on a timely basis;

- Significant cost overruns;

- Information indicating that the costs of internally developed software will significantly exceed the cost of comparable third-party software or software products, suggesting that management intends to obtain the third-party software instead of completing the internal development effort;

- The introduction of new technologies that increase the likelihood that management will elect to obtain third-party software instead of completing the internal project, and

- A lack of profitability of the business segment or unit to which the software relates or actual or potential discontinuation of the segment.

Amortization.

Paragraphs 4, 5 and 6 in ASC 350-40-35 provided guidance on amortization. As for other long-lived assets, the cost of computer software developed or obtained for internal use should be amortized in a systematic and rational manner over its estimated useful life. The intangible nature of the asset contributes to the difficulty of developing a meaningful estimate, however. Among the factors to be weighed are the effects of obsolescence, new technology, and competition. Management would especially need to consider if rapid changes are occurring in the development of software products, software operating systems, or computer hardware, and whether it intends to replace any technologically obsolete software or hardware.

Amortization commences for each module or component of a software project when the software is ready for its intended use, without regard to whether the software is to be placed in service in planned stages that might extend beyond a single reporting period. Computer software is deemed ready for its intended use after substantially all testing has been completed.

Internal-use software subsequently marketed.

In some cases internal-use software is later sold or licensed to third parties, notwithstanding the original intention of management that the software was acquired or developed solely for internal use. In such cases, ASC 350-40 provides that any proceeds received are to be applied first as a reduction of the carrying amount of the software. No profit is recognized until the aggregate proceeds from sales exceed the carrying amount of the software. After the carrying value is fully recovered, any subsequent proceeds are recognized in revenue as earned.

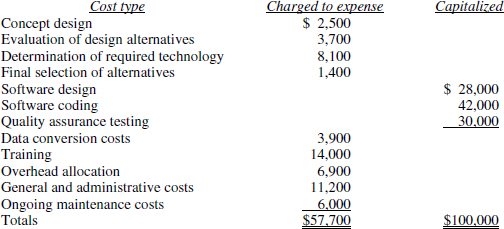

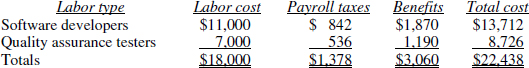

The Da Vinci Invention Company employs researchers based in countries around the world. The far-flung nature of its operations makes it extremely difficult for the payroll staff to collect timesheets, so the management team authorizes the design of an in-house, Web-based timekeeping system. The project team incurs the following costs:

Thus, the total capitalized cost of this development project is $100,000. The estimated useful life of the timekeeping system is five years. As soon as all testing is completed, Da Vinci's controller begins amortizing using a monthly charge of $1,666.67. The calculation follows:

$100,000 capitalized cost ÷ 60 months = $1,666.67 amortization charge

Once operational, management elects to construct another module for the system that issues an e-mail reminder for employees to complete their timesheets. This represents significant added functionality, so the design cost can be capitalized. The following costs are incurred:

The full $22,438 amount of these costs can be capitalized. By the time this additional work is completed, the original system has been in operation for one year, thereby reducing the amortization period for the new module to four years. The calculation of the monthly straight-line amortization follows:

$22,438 capitalized cost ÷ 48 months = $467.46 amortization charge

The Da Vinci management then authorizes the development of an additional module that allows employees to enter time data into the system from their cell phones using text messaging. Despite successfully passing through the concept design stage, the development team cannot resolve interface problems on a timely basis. Management elects to shut down the development project, requiring the charge of all $13,000 of programming and testing costs to expense in the current period.

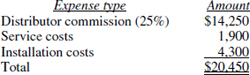

After the system has been operating for two years, a Da Vinci customer sees the timekeeping system in action and begs management to sell it as a stand-alone product. The customer becomes a distributor, and lands three sales in the first year. From these sales Da Vinci receives revenues of $57,000, and incurs the following related expenses:

Thus, the net proceeds from the software sale is $36,550 ($57,000 revenue less $20,450 related costs). Rather than recording these transactions as revenue and expense, the $36,550 net proceeds are offset against the remaining unamortized balance of the software asset with the following entry:

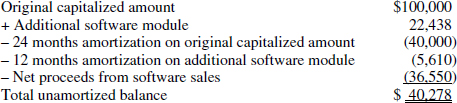

At this point, the remaining unamortized balance of the timekeeping system is $40,278, which is calculated as follows:

Immediately thereafter, Da Vinci's management receives a sales call from an application service provider who manages an Internet-based timekeeping system. The terms offered are so good that the company abandons its in-house system at once and switches to the ASP system. As a result of this change, the company writes off the remaining unamortized balance of its timekeeping system with the following entry:

Website Development Costs (ASC 350-50)

The costs of developing a website, including the costs of developing services that are offered to visitors (e.g., chat rooms, search engines, blogs, social networking, e-mail, calendars, and so forth), are often quite significant. The SEC staff had expressed the opinion that a large portion of those costs should be accounted for in accordance with ASC 350-50, which sets forth certain conditions which must be met before costs may be capitalized.

Per ASC 350-50, costs incurred in the planning stage must be expensed as incurred. The cost of software used to operate a website must be accounted for consistent with ASC 35040, unless a plan exists to market the software externally, in which case ASC 985-20, Software-Costs of Software to Be Sold, Leased, or Marketed, governs. Costs incurred to develop graphics (broadly defined as the “look and feel” of the web page) are included in software costs, and thus accounted for under ASC 350-40 or ASC 985-20, as noted in the foregoing. Costs of operating websites are accounted for in the same manner as other operating costs analogous to repairs and maintenance.

ASC 350-50-55 includes a detailed exhibit stipulating how a variety of specific costs are to be accounted for under its requirements.