Chapter 13

Duties of Public-Company Auditors: The Sarbanes–Oxley Act

In 1970, the Apollo space flight to the moon developed difficulties. As the Tom Hanks' movie Apollo 13 chronicled, the astronauts contacted the Manned Spacecraft Center in Texas, telling them “Houston, we have a problem.”

In the early 21st century, a different type of rocket was launched from Houston. Its name was Enron, and its stock price proverbially soared to the moon.

Eventually, Enron's atmospheric rise came to end. After numerous accounting irregularities were revealed, thousands of employees were laid off, and the Houston economy suffered. The Enron engine of economic prosperity had crashed—leaving Houston with a different kind of problem.

In response to the Enron debacle and growing concerns about accounting fraud, Congress amended the securities laws by enacting the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in 2002. Some hailed it as a cure for a seeming epidemic of accounting scandals; others euphemistically disparaged it as The Accountant Full Employment Act because of the increased number of auditors needed to fulfill its mandates. Other countries in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East soon thereafter enacted their own versions of this law.

Fans and foes alike commonly refer to the Sarbanes–Oxley Act as SOX, which is a contraction formed by the first letter of Sarbanes and the first two letters of OXley.

This chapter will examine the ethics rules enacted by SOX and the accounting body it established, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board. SOX's rules principally affect three core constituencies: publicly traded corporations, their executives, and their auditors. Each of these constituencies, as well as related rules affecting nonprofit organizations, now will be discussed.

HOW SOX AFFECTS PUBLICLY TRADED CORPORATIONS

The federal securities laws traditionally have imposed reporting requirements primarily on publicly traded corporations, called issuers. Although many privately held companies and nonprofit organizations voluntarily have opted to emulate SOX, most SOX rules are mandatory only for issuers.

SOX has imposed new rules on public companies relating to the establishment of Audit Committees, codes of conduct, and document retention policies.

Audit Committees

Long before SOX was enacted, most publicly traded corporations utilized Audit Committees to oversee their financial reporting practices. SOX, along with rules imposed by stock exchanges, have institutionalized the authority of Audit Committees in critical areas of corporate governance.

An Audit Committee is a subcommittee of a company's Board of Directors. Although Audit Committee members are selected from a company's Board of Directors, they otherwise must be independent of the corporation they serve. Therefore, company officers, paid outside lawyers and consultants, and shareholders who own more than 10% of a company's stock may not serve as Audit Committee members.1 In addition, to ensure financial proficiency, at least one member of the Audit Committee should have proven expertise in accounting or financial management.2

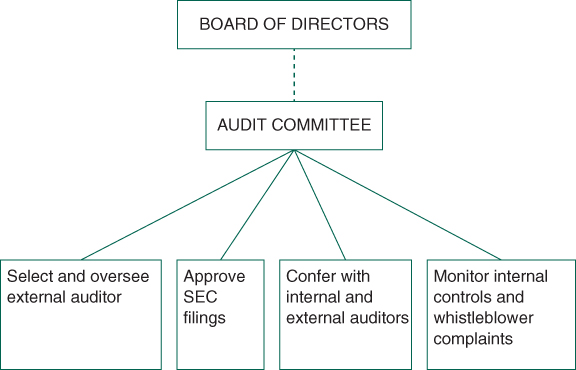

An Audit Committee has several responsibilities:

- It selects and supervises a company's independent auditor. It must preapprove all services provided by an auditor, including nonaudit services such as tax planning.

- It reviews all SEC filings, including financial statements, reports on the adequacy of internal controls, and published earnings forecasts. The most common SEC filings are the Form 10-Q quarterly report, the Form 10-K annual report, and the Form 8-K. Companies are required to file a Form 8-K whenever a major corporate event occurs, such as a merger, acquisition, director resignation, accounting restatement, or change of auditor.

- It meets periodically with internal and outside auditors. Internal auditors inform the Audit Committee about the reliability of company financial reports, the design and operation of its information systems, company risk management practices, and regulatory compliance. In contrast, external auditors principally focus on the content of the company's financial statements. This content includes the selection of critical accounting policies, practices, and estimates underlying the financial statements, significant unusual transactions, difficult or contentious matters, and the array of alternative treatments available to the company for complying with GAAP. To encourage candor, company officers are not allowed to be present during these discussions.3

- It monitors financial reporting risks. These monitoring mechanisms focus on ensuring the reliability of internal controls and reviewing whistleblower complaints about questionable accounting practices.

Figure 13-2 Roles Performed by an Audit Committee.

Despite initial optimism, there is little evidence that SOX's more stringent Audit Committee rules have improved the accuracy of financial reports or led to better stock market performance. In a bitter critique, law professor Roberta Romano refers to SOX as “quack corporate governance” that was enacted at a time when “the business community and the accounting profession had lost their credibility and become politically radioactive.”4 It also should be noted that Enron's Audit Committee was overseen by an independent, world-class accounting expert.5 History records how well that turned out.

Establishing a Code of Conduct

SOX has led to the universal adoption of codes of conduct by publicly traded companies.

To satisfy SOX, a corporation's code of conduct must promote:

- Honest behavior

- Ethical conduct relating to conflicts of interest

- Full, fair, accurate, timely, and understandable financial disclosures

- Compliance with all rules and regulations

- Timely reporting of violations to a designated compliance officer or the Board of Directors

- An impartial mechanism that rarely, if ever, exempts certain individuals or transactions from the code of conduct6

To discourage companies from authorizing exemptions from prescribed rules of conduct, companies granting waivers must promptly identify the person benefited and explain their reasoning in a Form 8-K filing. A company must prominently disclose its code of conduct on its website or in SEC filings, and the importance of the code of conduct repeatedly should be reinforced through periodic employee reminders and training sessions.

Establishing a Document Retention Policy

Campfires are meant for toasting marshmallows, not for burning incriminating documents. Although every camper knows this, members of the Arthur Andersen CPA firm apparently did not because, shortly before their firm's demise, they hosted a proverbial bonfire to destroy numerous documents relating to their Enron dealings. As a result, several Andersen personnel were indicted and imprisoned for criminal obstruction of justice.

To prevent this type of occurrence in the future, SOX has created strict new rules about the types of documents companies must retain and the length of time that they must maintain them.

The securities laws define the word record expansively to include all electronic and paper documents that relate to a company's plans, policies, or performance. Thus, marketing proposals, sales reports, internal memos, emails, and instant messages all must be retained. Furthermore, a company must archive all versions of a spreadsheet, including early versions that later were revised and did not directly influence final conclusions. Archived documents should be stored offsite in a secure location away from the company's premises.

The required retention period varies, depending on the nature of a document. SOX requires companies to retain stock ownership records, bank statements, training manuals, and most contracts forever. Other documents typically should be retained for seven years. Anyone who intentionally alters or destroys company documents to impede an investigation is subject to stiff penalties, including imprisonment for up to 20 years.7

HOW SOX AFFECTS COMPANY MANAGEMENT

SOX has imposed several new responsibilities and limitations on an issuer's management team regarding financial statement verification, executive compensation, auditor coercion, and whistleblower retaliation.

The Certification Requirement

One of SOX's most controversial elements is its requirement that top company officers vouch both for the effectiveness of their company's internal controls and the accuracy of its reported financial statements.

Under SOX, both the CEO and the CFO of a publicly traded company must, under penalty of perjury, certify the following:

- The company's quarterly and annual reports, in all material respects, fairly present its financial results

- The company's internal controls function properly

- They have disclosed to the Audit Committee and outside auditor all significant deficiencies and material weaknesses that could adversely affect the company's reporting

- They have told the Audit Committee and outside auditor about any fraud, whether or not material, involving management or other financial reporting professionals

- They have identified any necessary changes in internal controls and recommended appropriate corrective actions8

In large companies with multiple subsidiaries or divisions, it would be extremely burdensome for a CEO or CFO to be thoroughly familiar with the operations and internal controls of every segment. As a result, SOX permits the top executives of a company to rely on subcertifications signed by the top two executives of each segment.

The Disallowance of Incentive-Based Compensation

Prior to the enactment of SOX, unethical employees sometimes altered company financial results to increase their bonuses and other performance-based compensation. To remove this perverse incentive, SOX requires a company's CEO and CFO to forfeit personal income earned within the 12-month period following the issuance of erroneous financial statements if the error was caused by employee misconduct.9

This provision applies to all forms of income that are tied to reported company results, such as bonuses, sales incentive payments, and the receipt of stock options. Even capital gains earned by these officers from the sale of company stock during this 12-month period must be forfeited.

This forfeiture rule is known as a claw-back provision because the company, like an angry tiger, metaphorically sticks out its sharp claws to ferociously grab back undeserved executive profits.

Like many well-intentioned laws, SOX's claw-back provision creates various perverse consequences. For instance, critics contend that financial statements that should have been corrected might now remain uncorrected because of senior officers' resistance to forfeiting previously received bonuses. Also, commentators note, the affected senior officers can avoid this provision easily by delaying their capital gains from sales of stock beyond the 12-month claw-back period.

The Disallowance of Company-Provided Loans

Traditionally, key executives have relished receiving employer-provided, low-interest loans as a fringe benefit. Many employers gladly encouraged executives to accept this fringe benefit because the prospect of one day having to repay these loans discouraged executives from accepting employment elsewhere.

Even though employers and employees alike found this practice to be mutually beneficial, many members of Congress considered these loans to be inappropriate. As a result, in adopting SOX, Congress prohibited publicly traded companies from granting or arranging loans for directors and officers.10

Prohibitions against Coercion

To fortify auditor independence, SOX prohibits directors, officers, and others acting under their direction from pursuing “any action to fraudulently influence, coerce, manipulate, or mislead” a company's auditor.11

Prohibitions against Whistleblower Retaliation

As the earlier chapter on whistleblowers discussed, SOX protects whistleblowers in two ways.

If a vindictive executive of a publicly traded company retaliates against a worker, such as by denying a deserved pay raise or promotion, the worker can hold the executive and the company liable for monetary damages.12

In addition, SOX makes it a crime for anyone to deliberately retaliate against a whistleblower who truthfully informs a law enforcement officer about the commission of a federal offense, such as securities fraud. As a result, the government may prosecute a company executive who retaliates against a whistleblower. This crime is punishable by up to 10 years in prison.13

THE IMPACT OF SOX ON AUDITORS

SOX has impacted auditing firms by creating the PCAOB, toughening independence rules, and toughening document retention rules.

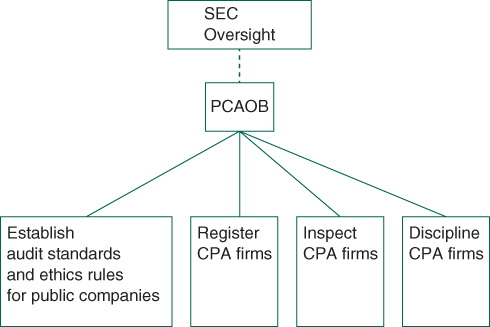

PCAOB Regulatory Oversight

The Jurisdictional Swamp

When Frank Broaker received his CPA license from the state of New York on February 23, 1893, he earned momentary fame by becoming the first CPA in American history. Since that historic date, CPAs, like the far older professions of medicine and law, always have been subject to the license-granting and disciplinary authority of their home state.

Figure 13-3 Roles Performed by the PCAOB.

Furthermore, the accounting profession, through the auspices of the AICPA, largely has set its own ethical and substantive professional standards without governmental interference.

This long-standing regulatory environment of state licensing and professional self-regulation was altered in two major ways when SOX established a national body known as the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board, or PCAOB.14

First, CPA firms wishing to audit public U.S. companies must register with the PCAOB and agree to its mandates. Thus, although individual CPAs still need a state license to practice accounting, CPA firms that wish to audit public companies must, in essence, obtain a second, federally mandated permit.15

Second, SOX has installed the PCAOB as the dominant standard-setter in charge of setting public-company auditing rules. Thus, the PCAOB, as overseen by the SEC, sets the rules that govern audits of public companies, and the AICPA continues to set the rules governing audits of all other companies.16

Registering with the PCAOB

CPA firms that wish to audit publicly traded companies must disclose their fee structures, quality control policies, and audit clients in an initial registration filed with the PCAOB.

Once approved, a CPA firm must submit routine annual reports to the PCAOB that specify the nature and amounts of their fee income. In addition, a firm must file a Special Report within 30 days after a reportable event occurs.

Reportable events are occurrences that potentially provide insights into a firm's competence. For instance, a reportable event arises when a firm withdraws a previously issued audit opinion or a CPA firm or its partners are sued for professional misconduct.

As part of an ongoing qualification process, CPA firms must undergo periodic quality control inspections.17 The PCAOB is authorized to impose disciplinary sanctions on audit firms that do not adhere to its directives.

Independence Rules

To minimize the influence of close personal relationships on professional independence, SOX imposes several new restrictions on auditors of public companies. Thus, the independence rules for auditing public companies incorporate the foundational principles of the AICPA's Code of Conduct, as discussed in an earlier chapter, and add in tougher requirements concerning the use of concurring audit opinions, auditor rotation, CPA firm personnel transitioning to work for their clients, the performance of nonaudit services, and partner compensation relating to nonaudit services.

The Use of Concurring Auditor Opinions

If a doctor ever told you that a disease permanently will enlarge your ears to the size of watermelons, you surely would run to another doctor for a second opinion. In a similar vein, the PCAOB requires the lead auditor on a public-company engagement to also get a second opinion.

The lead auditor may obtain this concurring opinion from another qualified partner within the same firm or, alternatively, from an experienced CPA at another firm. This second auditor is referred to as the engagement quality reviewer or concurring partner.

Auditor Rotation

The American View

Under SOX, the lead partner on an audit engagement and the concurring partner must relinquish their roles every five years. This process, called partner rotation, requires that, after the two top partners on an audit engagement have served a client for five years, they must sit on the sidelines and cannot resume involvement with that client for a subsequent period of five years.18

Figure 13-4 Auditor Rotation.

Although partner rotation is now widely accepted, some have suggested that mandatory audit firm rotation would further improve auditor independence.

According to a recent study, the largest 100 U.S. companies have used the same audit firm for an average of 28 years.19 Because of this longevity, some regulators question whether CPA firms themselves should be rotated to prevent ferocious audit watchdogs from transforming into meek pussycats.

Supporters of audit firm rotation assert that if an auditor knows that a successor eventually will be reviewing its work, mandatory rotation will have a salutary impact on audit quality. In the United States, however, groups such as the Center for Audit Quality oppose this concept.20 Mandatory firm rotation, they claim, would increase audit costs and cause unnecessary client disruption. A scarcity of qualified auditors might also arise in certain business sectors, especially for companies with global operations.

In 2013, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly approved legislation that would bar the PCAOB from requiring mandatory audit firm rotation. Consequently, mandatory rotation rules are highly unlikely to be imposed in the United States in the foreseeable future.21 As alternatives, two intriguing proposals have been suggested.

One suggestion is that companies should pay audit fees into a centralized fund that would then assign an auditor from a pool of qualified CPA firms. Supporters contend that this approach would prevent companies from choosing an auditor that is likely to be excessively compliant, as can occur under the present system. Opponents, however, scoff at the notion that auditors are as interchangeable as, say, a pair of white socks. Rather, they argue, companies should be allowed to select their auditor because CPA firms have unique skills, talents, and industry expertise that allow them to perform certain kinds of audits with superior accuracy and efficiency.

Another suggestion is that the responsibility for ensuring the accuracy of financial statements should be turned over to the insurance industry. Supporters of this approach say that insurance providers should assess the risks of a company misstating its financial position and then issue an insurance policy guaranteeing that the company's statements comply with GAAP. To minimize policy losses, the insurance provider, in turn, would hire a tough auditor to make sure that companies covered by such an insurance policy meticulously comply with their financial reporting obligations.

The International View

In a significant change to current practices, the European Parliament has just begun limiting auditor–client relationships to a maximum period of 10 years. These new rules apply to audits of publicly traded companies and other so-called public-interest entities that are within its jurisdiction.22 The success or failure of this new audit firm rotation mandate surely will influence the global debate on this issue for years to come.

The Waiting Period before Joining an Audit Client

Figure 13-5 Auditor Waiting Period before Working for an Audit Client.

After an extended period of interaction, it is not uncommon for an audit client to extend a job offer to an impressive member of its external auditor's engagement team. When this occurs, the former audit staff member benefits from a new opportunity, the client obtains a talented new employee, and the CPA firm has a happy member of its unofficial alumni club ascend to a client decision-making role. The apparent success of this arrangement is confirmed by the fact that, roughly one-third of the CFOs heading Fortune 1000 companies previously worked for their company's auditor.23

Despite the apparent benefits of this revolving door policy, it creates a serious familiarity threat to objectivity and independence. Recognizing this threat, SOX prohibits accountants from immediately moving from their auditor's desk to a client's executive suite. More specifically, SOX provides that anyone who “participated in any capacity in the audit of a company” is subject to a one-year cooling-off period before joining a publicly traded client as its CEO, CFO, Controller, or Chief Accounting Officer.24

The Provision of Nonaudit Services

The SEC has observed that, in the modern commercial world, CPA firms have “woven an increasingly complex web of business and financial relationships with their audit clients.”25 Consequently, self-review and management participation threats seem to keep popping up more frequently than critters in a game of Whack-a-Mole. To disentangle auditors from their clients, SOX mandates that CPA firms may not perform the following nonaudit services for their audit clients:

- Bookkeeping

- Financial information system design and implementation

- Valuation and appraisal services

- Actuarial services

- Hiring, leasing, or other managerial decisions

- Legal, investment banking, or expert witness services

- Certain tax services

Partner Compensation for Nonaudit Services

Under SOX, it inappropriate for an audit partner to overtly market nonaudit services to an audit client. To eliminate auditors' incentives to cross-sell other accounting services, audit partners' compensation cannot be based, directly or indirectly, on the amount of nonaudit income that a partner procured for the firm.26

Document Retention

An auditor is required to retain all audit working papers for five years. This mandate requires auditors to retain all versions of their business records, including any documents that are inconsistent with the conclusions ultimately presented in audited financial statements.27

THE IMPACT OF SOX ON TAX PRACTITIONERS

Because SOX was enacted in response to turbulent securities markets, tax practitioners commonly assume that an understanding of SOX is irrelevant to their endeavors. However, this is a misperception because certain SOX provisions, such as those relating to independence, document retention, and Audit Committee preapprovals of tax services, are highly relevant to tax professionals.

Under SOX, audit firms may not provide the following tax services:

- Taxpayer advocacy in a judicial or administrative hearing

- Taxpayer representation in an IRS audit

- Tax return preparation for executives involved in a client's financial reporting oversight process, such as the company CEO, CFO, and Controller28

However, it is noteworthy that an auditor may provide tax return preparation and advisory services to an audit client, as long as the client's Audit Committee preapproves these services. Tax advisers also must proceed with caution when recommending certain types of tax-motivated transactions.

THE IMPACT OF SOX ON NONPROFIT AND PRIVATE ORGANIZATIONS

Financial scandals can have a devastating effect on charitable institutions, as well as private capital markets.

As an example, after the September 11 terrorist attacks, the Red Cross received a veritable avalanche of donations to assist the victims. Out of a desire to satisfy unmet needs elsewhere in the world, the Red Cross diverted these contributions to other purposes, contrary to donors' express desires. Feeling betrayed, outraged donors lobbied Congress to broaden the scope of SOX's accountability rules to encompass charitable organizations. Congress responded by imposing its document retention and whistleblower antiretaliation rules on nonprofit organizations and privately held businesses.29

Furthermore, scandals such as the Red Cross incident and Bernie Madoff's misappropriation of charity funds have forced charities to recognize that their very existence directly depends on public confidence in their integrity and prudent management. As a result, to reassure donors, many nonprofit organizations voluntarily have adopted other aspects of SOX.

EXERCISES

The Audit Committee

- The Audit Committee of a publicly traded company is comprised of three members. One of the members is a retired Chief Financial Officer of a global bank headquartered in New York. She has extensive experience in managerial finance. However, she is not a CPA and never has worked in accounting or auditing.

The other two members of the Audit Committee inherited shares of stock in the corporation from their parents and have no experience in corporate management or accounting. These two members each own 7% of the corporation's stock.

Does this corporation's Audit Committee comply with SOX?

- A company's Audit Committee recently held a three-hour meeting with its internal auditors, its CFO, its Controller, and its external auditors. The meeting was held to investigate reports filed by two internal auditors about deficiencies in the company's internal controls and accounting department personnel policies. Both internal auditors were introduced to the meeting participants and were asked to participate in Question and Answer sessions about their concerns. Did the company do anything wrong?

- The New York Stock Exchange requires all companies traded on it to utilize internal auditors. Commonly, companies do not directly hire their own internal auditors. Rather, internal auditors often are employed by an outside CPA firm, and client companies outsource their needs for internal auditors from these outside CPA firms.

- Why don't companies hire their own internal auditors?

- Although companies outsource their internal auditors from CPA firms, they never outsource them from their own external auditor. Why not?

- When a publicly traded company acquired the operating assets of another company in a cash-for-assets deal, the overall purchase price had to be allocated among the assets. Due to time pressures, the company's CFO decided to retain the company's auditors to perform this asset allocation task. The company's auditors are highly reputable and have substantial experience valuing the kinds of assets that were involved in the acquisition. The auditors submitted a written bid, and they submitted the lowest fee of all bidders who participated. Do you applaud the CFO's efforts for getting all of this done on time and on budget?

- A CPA just left her position as an audit manager at a prominent regional CPA firm to start her own accounting practice. She is interested in marketing herself to serve on companies' Audit Committees. However, she has no interest in serving as a company director because members of Boards of Directors require strategic and marketing skills that she lacks. Are her marketing efforts to get appointed to serve on a company's Audit Committee likely to be successful?

Duties of Managerial Employees

- As the accountant in charge of Current Asset reporting for a publicly traded company, you recorded inventories at historical cost in a draft version of the company's quarterly balance sheet. Just before sending this version to the company's CFO, you realized that inventory had to be recorded at lower of cost or market. As a result, you updated your calculations and submitted a corrected version that reported a loss write-down in inventory value from cost to market. To eliminate possible confusion, you put the heading FINAL in bold letters on the submitted version and deleted the obsolete version from the company's server. You did perform a backup of the final version on the company's server, with a clearly worded description to facilitate later retrieval. Did your actions comply with SOX?

- A publicly traded corporation grants its CEO a bonus of $100,000 for every million dollars by which company annual net income exceeds $60 million, up to a specified maximum bonus. Last year, the company's reported net income was $65 million, so the CEO received a bonus of $500,000.

In performing your duties as an internal auditor, you discovered that company sales were overstated last year by $5 million. Operating expenses were not affected and the company's effective tax rate correctly was reported to be 40% of pretax profits.

When you told the CEO about this misstatement, he shouted in disgust that your proposed restatement of the company's prior-year earnings will “cost him his entire bonus.” Is he correct?

- To entice a new Chief Operating Officer to leave her current job, a publicly traded stock brokerage firm wants to extend credit to her in the following situations:

- The company will lend $100,000 to its COO at the prevailing fair rate of interest, after this loan has been approved by a majority vote of the company's shareholders.

- The company will coordinate with a local bank to arrange a home relocation loan that will help the company attract a new COO by enabling her to afford to buy a home near company headquarters.

- The company will permit the COO to charge up to $10,000 of business expenses to a widely used credit card guaranteed by the firm.

Which of these transactions is permitted under SOX?

- Brett Terrible, your department supervisor, hates you for informing the federal government that he has been taking advantage of his position as the Controller at a publicly traded company to embezzle its funds. As part of his scheme, he sends international wire transfers to secret Swiss bank accounts. He then covers up this embezzlement by labeling the associated disbursements as Bank Fees Expense.

Rather than lower your wages and financial benefits, he simply has given you unchallenging job assignments in the hope that you will quit out of boredom. He confided in an email to a friend that, by “thwarting you from proving financial harm, you won't be able to touch him.” You have obtained a copy of this email, but you know realistically that hiring a lawyer to sue him would be prohibitively expensive.

- Is there a way for you to ensure that Brett will be punished?

- Would your answer be the same to the preceding question if your company was privately owned by a single entrepreneur?

- Would your answer be the same to the question if your company was a nonprofit foundation dedicated to the prevention of climate change?

Duties of Auditors

- “Auditors, like a good set of car tires, need to be rotated every so often.”

- Under what circumstances, if any, must a lead audit partner be rotated?

- Under what circumstances, if any, must a concurring audit partner be rotated?

- Under what circumstances, if any, must an entire audit firm be rotated?

- Should audit firms be allowed to continue as a client's auditor forever, or should audit firms rotate? Identify the pros and the cons.

- PCAOB inspectors discovered that, in making proposals to potential audit clients, a large accounting firm used the following phrases:

- Your auditor should be a partner in supporting and helping you achieve your goals.

- We will help you achieve your desired outcome when our audit teams are confronted with an issue, and we will bring out our best in-house advisors when your matter merits consultation with our National Office.

- We stand by all conclusions reached and will not second guess our joint decisions.

Do any of these marketing-oriented statements concern you?

- You spent the last three months working as part of an engagement team that was auditing Vintage by Jessica, a fast-growing, publicly traded, high-fashion cosmetics company headquartered in the heart of Manhattan and Austin.

One day after the client's financial statements were issued, Alison, the partner in charge of the audit team, called to tell you that she will be accepting a position at this client as its new CFO. The partner also invited you to join “her new team” and relocate to this client's San Francisco office as a junior Financial Forecasting Associate for Asian Operations. You contacted the client to accept this offer on November 5 and plan to resign your current position on November 17. You also called your ace adviser Joyce Howard and attorney Badger Lee for advice. How long do you have to wait before commencing work with this client?

- “A company should be prohibited from removing its auditor without good cause within the first five years of the auditor's service to the client.” Do you agree?

- A CFO and CEO potentially are subject to huge financial penalties if they incorrectly certify to the SEC that their company's internal controls function properly, and they do not. They similarly are subject to huge penalties if they certify that their company's financial statements fairly present its financial position, but they do not.

Should these executives be allowed to obtain insurance that will reimburse them for the amount of these penalties if they mistakenly submit a certification to the SEC that proves to be erroneous? Identify the pros and cons of insurance coverage being available.

- “Before a publicly traded company may terminate its auditor, it should have to present its reasons for termination to the PCAOB and obtain the PCAOB's approval.” Do you agree?

- “After a food inspector examines a restaurant's food safety practices, the food inspector gives the restaurant a letter grade that, by law in my state, must be posted in the front window of the restaurant. Auditors, though, do not have to post their PCAOB inspection reports on their websites. I suggest that the PCAOB should issue auditors ratings that they have to display on the home page of their websites. If restaurant food is deficient, I will never go back there again. But how am I, a simple investor, supposed to know if an auditor's work is deficient?”

- Should the PCAOB give auditors numerical scores or letter grades, so the investing public can better assess audit quality?

- How often are auditors inspected?

SOX and Tax Practitioners

- Under what circumstances, if any, should an accounting firm be allowed to concurrently prepare a corporation's tax return and perform its audit?

Nonprofit Organizations and SOX

- A nonprofit organization called the Preserve Your Hair-Itage Foundation is committed to funding medical research projects aimed at developing a vaccine for male-pattern baldness. The organization believes that its contributions over the long run will be 20% higher if it institutes a code of conduct, an antiretaliation whistleblower policy, and an audit committee comprised of well-regarded financial executives. The CEO of this organization estimates that it will have to spend 5% of its annual revenues to maintain these policies. Some members of the organization's Board of Directors oppose spending a higher percentage of the organization's donation revenue on overhead.

- Is this organization required to adopt these new policies under SOX?

- Should it adopt these new policies?

- Over time, your nonprofit organization, Kidz Against Cancer, has grown to generate over $3 million in annual contributions from donors. One of your donors is a very wealthy individual who has indicated that she is considering creating a trust fund in her grandchildren's name to help fund your organization. If she agrees to donate, the likely amount will exceed $50 million. All of your other donors typically contribute less than $100 to the cause.

- Are there any aspects of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act that your organization is required to adopt?

- Are they any other aspects of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act that you believe your organization should consider adopting?

- Charitable organizations often find that potential donors are hesitant to contribute to charities that spend an excessively high percentage of their donations on fundraising costs rather than their core mission. Knowing this, a charity that is dedicated to helping wounded war veterans deliberately misclassified marketing expenses as War Veteran Service Expenditures. This resulted in a misclassification of expenditures, category by category, but it did not misstate total expenditures.

- Did this charity violate SOX?

- Did this charity commit any other violations?

Comprehensive Problems

- The following individuals all work for a CPA firm with 17 offices located through the United States. Which of these individuals must wait one year before commencing work for their client?

- An audit partner who served as the lead partner on a publicly traded client's audit engagement team over the past three years. The audit partner has been offered a position as the Chief Accounting Officer of this client.

- An audit partner who never served on the engagement team of the client that wishes to hire her, but she did serve recently as the lead partner on several other audits of publicly traded clients that conduct business in the same industry. The audit partner has been offered a position as the Chief Financial Officer of this client.

- A concurring partner who served as this publicly traded client's audit engagement team over the past two years. The audit partner has been offered a position as Head of Investment Portfolio Analysis for this client.

- A junior staff auditor who worked on a family-owned client's audit engagement team over the past three years. This staff auditor has been offered a position as the Chief Accounting Officer of this client.

- A tax partner who served as a tax consultant to a publicly traded client over the past nine years. The tax partner has been offered a position as the Chief Executive Officer of this client.

- When an auditor issues an audit report, it has the discretion to highlight certain items that might be of particular concern to investors. Recently, De Lite, CPAs, informed a client's Audit Committee that it intended to highlight a certain matter in its audit report. The Audit Committee patiently discussed this issue with its auditors and said that it understood that its auditors believed that they had a duty to make this disclosure, but the Audit Committee “respectfully disagreed.” A few minutes later at that meeting, the Audit Committee told De Lite, CPAs, that it was “by the way, seriously thinking about doing a lot more of its tax planning and compliance work in-house.” The representatives of De Lite, CPAs, who were present understood that such an action would jeopardize a significant portion of the revenue earned from providing tax services to this client, which could result in layoffs and unused space at De Lite's local office nearby.

Did the client violate the Sarbanes–Oxley Act?

- A CPA firm requires recent college graduates joining its audit practice to sign an employment contract that specifically prohibits them from accepting “future employment at any time with any audit client for which they participated as a member of the audit engagement team.” Assume that such an agreement is enforceable.

- What are the pros and cons of such a contract term?

- If an audit firm asked you to agree to such a contract term as a condition of employment, would you consider this provision to be reasonable? What factors might make you view it as unreasonable?

- Would you expect a CPA firm to view favorably, or view unfavorably, audit staff members who quit to accept an in-house position employment with an audit client?

- Would your answer to the preceding question depend on whether the employee quit two weeks before the client's audited statements had to be filed with the SEC?

- The Detroit accounting firm of Norman, Braverman, Potvin, and Benjamin, CPAs, has always had a cordial, but frequently contentious, relationship with its publicly traded audit client, Jay-Scott, Inc. Jay-Scott sells beverages and must collect a refundable deposit on every glass bottle and aluminum can sold. Lately, for instance, this audit client angrily accused the firm of “sabotage” for failing to allow it to record a portion of these refundable deposit collections as revenue transactions in the year of collection. According to the management of Jay-Scott, statistics prove that 20% of all deposits will be claimed by customers, and therefore, the forfeited deposits constitute immediate revenue.

Jay-Scott, Inc. retains this accounting firm annually to perform both tax preparation services and its audit. When the CPA firm informed Jay-Scott that its fee for tax services was going to increase by 4% during the upcoming year, Warren Harris, the CEO of Jay-Scott, said, “That's not being fair to you. You work hard, so let's up that to a 30% increase.” Did this client violate SOX?