Chapter 14

Duties of Tax Professionals

The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Jimi Hendrix primarily sang about peace and love, but they also vocalized in unison about their hatred for one thing—taxes. These legendary musicians expressed their outrage about Britain's high tax burden in the classic rock tunes Tax Free and Taxman, and some band members even renounced their British citizenship to move to countries with more attractive tax rates. Soon after singing that he did not “wanna be a tax exile,” Sting felt so stung by England's 95% top income tax rate that he too abandoned his homeland.1

In the following lyrics to Taxman, the Beatles satirized British tax collectors for letting them keep only 1 of every 20 dollars of pretax earnings:

Let me tell you how it will be,

There's one for you, nineteen for me,

Should five percent appear too small,

Be thankful I don't take it all,

'Cause I'm the Taxman

Although few people dislike taxes as much as these British rockers did, it is a universal truth that no one likes paying taxes. As a result, many citizens turn to accountants as guardians who can protect them from the perceived excesses of the Taxman. But do accountants owe their loyalties solely to those who hire them? Or, do accountants have a civic obligation to moderate their client advocacy because, as Supreme Court Justice Holmes reminds us, “taxes are the price we pay for civilized society?”2

According to the AICPA's rules of professional conduct, accountants have dual roles—they have “both the right and the responsibility to be an advocate” and “a duty to the tax system” that sometimes transcends client advocacy.3 This chapter will explore how tax professionals, like acrobats on a tightrope, must achieve a proper balance.

PROFESSIONAL RESPONSIBILITIES IN TAX PRACTICE

The Governing Sources of Guidance

The AICPA's Tax Executive Committee has developed standards that delineate accountants' ethical duties in preparing tax returns, providing taxpayer representation, and rendering tax advice. These enforceable standards are known as the Statements on Standards for Tax Services, or SSTS for short.

The SSTS applies to all aspects of federal, state, and local tax practice and complements federal and state laws regulating tax professionals. The federal government's rules collectively are reflected in U.S. Treasury Circular No. 230, Internal Revenue Code penalty and documentation provisions, court rulings, and various interpretative IRS Regulations and pronouncements.

The SSTS technically only applies to AICPA members. However, as a practical matter, the SSTS effectively has the force of law because many state boards of accountancy have adopted similar rules, and courts apply the policies underlying the SSTS in gauging all tax practitioners' conduct. As a result, in the discussions that follow, we will assume that all tax professionals must adhere both to federal mandates and the SSTS.

The SSTS Framework

The SSTS is comprised of seven standards, each of which has three sections: The Introduction, the Statement, and the Explanation.

These standards guide accountants in their roles as tax return preparers, tax planners, and taxpayer representatives. Moreover, the SSTS applies to accountants who work in public practice, as well as in industry and government.4

DUTIES AS A TAX RETURN PREPARER

Tax return preparation is big business. There are nearly 700,000 paid tax return preparers, with H and R Block alone generating $2 billion annually in fees.5

Tax compliance work involves preparing tax filings for individuals, such as federal, state, and local income tax returns, gift tax returns, and estate tax returns. Business entities also rely on in-house accountants, as well as outside tax return preparers, to complete income, payroll, sales, and property tax returns. Even nonprofit organizations, such as hospitals, colleges, religious groups, and charities, are required to submit tax filings to the IRS.

The tax preparation process involves up to seven steps: Obtaining client information, using estimates to fill in information gaps, formulating tax positions, evaluating uncertain tax positions, completing the tax return, correcting errors on previously submitted tax returns, and returning client documents. Each step will now be examined.

Obtaining Client Information

Before preparing a tax return, accountants have to gather information from their clients. Tax return preparers are not auditors, and they generally do not have a duty to verify that client information is accurate. Rather, to expedite the tax return preparation process, accountants generally may “in good faith rely, without verification, on information furnished by the taxpayer or by third parties.”6

In some cases, however, tax return preparers do have to verify information furnished by a client. This duty arises only when client information “appears to be incomplete, inaccurate, or inconsistent…on its face” or information appears to be unreliable based on “other facts known” to the tax return preparer.7

An interesting dilemma arises when a tax return preparer knows facts that contradict client-provided information, but privacy rules preclude the tax return preparer from utilizing these facts. This type of predicament might arise, for example, when one client rents an entire building to another client, but the landlord's reported rent revenue does not match the buyer's reported rent expense.

Assume, as an illustration, that an accountant provides services to both a Hong Kong manufacturer and its U.S. distributor. The accountant knows from reviewing the manufacturer's books that the U.S. distributor earned $970,000 commissions last year, but this distributor tells the accountant that it only earned $610,000. Should the accountant violate his duty of confidentiality and insist that the U.S. distributor report its full $970,000 of earnings? Or, should the accountant disregard the contradictory information gleaned from the Hong Kong company's books and permit the distributor to underreport its income? Although the SSTS does not provide definitive guidance for resolving this issue, it does firmly remind accountants to never violate the duty of confidentiality.

Filling in Information Gaps

In the early 1920s, Broadway star George M. Cohan sang the blues when the IRS told this show tunes maestro to show documentation. Rather than tap dance around the issue, a federal Court of Appeals chastised Cohan for poor recordkeeping, which created “inexactitude of his own making.” However, convinced that Cohan's expenses were legitimate, the court allowed him to deduct a “close approximation,” noting that “absolute certainty in such matters is usually impossible and is not necessary.”8

In recognition of this long-standing rule, accountants generally may prepare tax returns based on reasonable client estimates. The use of estimates to fill in information gaps, however, is subject to three important limitations.

First, a tax return preparer should not present estimated amounts in a manner that creates a “misleading impression about the degree of factual accuracy” present.9 For example, if a taxpayer sells 100 shares of stock that had an estimated cost of “roughly $7 per share” many years ago, she should not report the stock's total cost as “$702.43” to mask the imprecision of her estimate.

Second, when estimates are so extensive that the overall accuracy of a tax return is in doubt, a tax return should disclose this use of estimates. The SSTS identifies four circumstances in which estimates are so all-pervasive that their use requires disclosure:

- The taxpayer was unavailable to participate in the tax return preparation process due to death or illness

- The taxpayer's records became unavailable due to a computer failure, fire, or natural disaster

- The taxpayer did not receive information from a partnership or other pass-through entity, so the taxpayer's profit share had to be estimated

- Pending judicial proceedings, such as a bankruptcy, may materially affect reported amounts10

Finally, the use of estimates is prohibited altogether for specified expense activities in which taxpayers commonly exaggerate deduction claims. For example, the Internal Revenue Code expressly disallows deductions for business-related meals, entertainment, travel, and automobile usage unless taxpayers satisfy strict documentation requirements.11

| Does Adequate Documentation Exist? | What May Be Claimed on a Tax Return? |

| Yes | A preparer may rely on information furnished by a taxpayer, unless:

|

| No | The taxpayer's estimates generally may be used, but:

|

Figure 14-1 Assessing Tax Return Positions.

Formulating Tax Return Positions

Just about everyone hates the complexity of our tax system. One frustrated commentator compared our tax system to a blood-sucking vampire, proclaiming that we should “drive a stake through its heart, bury it, and hope it never rises again to terrorize the American people.”12 Others salute the Internal Revenue Code for its pursuit of fairness, but acknowledge that, if “all the accountants…and a convention of wizards” were brought together, they still could never figure out the Tax Code's manifest uncertainties.13

Because of the uncertainties inherent in tax analysis, tax return preparers have to exercise sound professional judgment in deciding whether to claim a tax return position. A tax return position is an item or amount that a taxpayer reflects on a tax return after receiving specific advice, or an assertion that a tax return preparer, with knowledge of all material facts, has concluded is appropriate.14 Commonly, a tax return position is the numerical amount of an income, deduction, or credit item that a taxpayer has decided to present on a tax return. However, tax return positions also include subtle determinations concerning the character or tax treatment accorded to elements appearing on a tax return. For example, if an accountant assists a partnership in characterizing whether funds transferred to a partner are compensation, a loan, or an ownership distribution, the resulting tax return presentation is a tax return position.

Evaluating Uncertain Tax Positions

Every gambler dealt a questionable poker hand knows that “you gotta know when to hold 'em and know when to fold 'em.”15 In a manner of speaking, before claiming a questionable tax return position, a tax return preparer also has to assess whether to “hold 'em or fold 'em.”

When a tax position is uncertain, the SSTS requires accountants to make a prediction about the likelihood of the position ultimately being sustained by a court or administrative body. This forecasted chance of success should be based on “a well-reasoned construction of the applicable statute, well-reasoned articles or treatises, widely accepted research tools, or pronouncements issued by the applicable taxing authority.”16

Understanding the Threshold Standards

Traditionally, five alternative labels are applied in characterizing the likelihood of a tax return position being upheld. These benchmarks, in order from least restrictive to most restrictive, are the Not Frivolous standard, the Reasonable Basis standard, the Realistic Possibility of Success standard, the Substantial Authority standard, and the More Likely Than Not standard.

- The Not Frivolous Standard

A tax position is frivolous if a person asserts an obviously improper position out of a desire to “delay or impede” the administration of our tax system. For example, if a taxpayer claims a dependency deduction for a pet turtle as a “beloved member of the family,” this claim clearly would be frivolous. Asserted tax positions should always satisfy the not frivolous standard, both for ethical reasons and because substantial penalties and disciplinary action may result.17

- The Reasonable Basis Standard

A tax position has a reasonable basis if it has been viewed favorably by at least one authoritative source, such as a court decision or IRS pronouncement.18 The reasonable basis standard is satisfied if, as a rough approximation, there is at least a one in five chance that a tax position, if challenged, would be upheld in a judicial or administrative hearing.

To illustrate, assume that a business owner who frequently has been robbed brings her ferocious dog to work to alert her to possible intruders. Feeding and caring for her dog is expensive, so she has decided to claim these costs on her income tax return as a business security warning system expense. The reasonable basis standard would be met if there is at least a 20% chance that a court or the IRS will give an approving “Woof!” to this tax return assertion.19

- The Realistic Possibility of Success Standard

A tax position satisfied the realistic possibility of success standard if a tax practitioner sincerely believes that there is at least a one in three chance that a tax position, if challenged, would be sustained on its merits in a judicial or administrative hearing. To illustrate, assume that a petite nursing home worker wants to deduct her gym membership cost as a job expense because she frequently has to lift heavy patients out of bed. If there is at least a one-third chance that a court or other authority will agree, this tax position satisfies the realistic possibility of success standard.20

- The Substantial Authority Standard

A tax position meets the substantial authority standard only if it has significant authoritative support. The presence of substantial authority is a qualitative, not a quantitative, issue. A tax professional must examine various sources of tax guidance, including court decisions, the Internal Revenue Code, U.S. Treasury Regulations, and other pronouncements issued by taxing authorities. Careful professional judgment is required in making this determination because certain authoritative tax viewpoints must subjectively be weighted more heavily than others. For example, Appeals Court decisions usually are accorded more weight than lower court opinions, recent court opinions trump older opinions that appear to be outdated, and IRS rulings based on fact patterns that are virtually identical to a taxpayer's situation merit greater weight than those that diverge from a taxpayer's circumstances.

Among tax professionals, a tax position is considered to have substantial authority if it subjectively has roughly a 40% or greater chance of being sustained on its merits in a judicial or administrative hearing.21

- The More Likely Than Not Standard

As its name suggests, the more likely than not standard is met when the weight of authority in favor of a tax position exceeds the weight of authority opposing it. Simply stated, the odds of a position being sustained, if challenged, must exceed 50%.

Many commentators do not favor this threshold standard because, they claim, it unduly restricts taxpayers from advocating novel tax positions in good faith. In recognition of this concern, tax rules usually impose this stringent standard only in evaluating potentially abusive transactions that historically have been utilized to evade taxes.22

| REPORTING STANDARD | ODDS OF A POSITION BEING SUSTAINED BY TAXING AUTHORITY OR COURT |

| Not Frivolous | Very low |

| Reasonable Basis | At least 20% |

| Realistic Possibility of Success | At least 33 1/3% |

| Substantial Authority | At least 40% |

| More Likely Than Not | Above 50% |

Figure 14-2 Tax Reporting Standards.

Applying the Threshold Standards

Because tax return audit and penalty rates typically are quite low, conniving taxpayers sometimes gamble that a dubious tax return position will, on average, yield a juicy payoff. An accountant is not a pit boss, however, and an accountant's office is not a casino. Even if a Las Vegas bookie might drool over how the low odds of a tax audit favor taxpayers, accountants must disregard such considerations and act ethically to uphold our tax system.

In deciding whether an uncertain tax return position is permissible, a tax return preparer should, in principle, follow up to three analytical steps.

As a starting point, a tax return preparer ordinarily should apply the substantial authority standard.23 Thus, if a tax position has a roughly 40% or greater chance of being sustained, it usually is ethical to assert it.

Second, though, before claiming a tax position, a tax return preparer must check to see if the taxing authority prescribes a standard higher than the substantial authority standard. If the tax law mandates a standard that is higher than the reporting standard mandated by the SSTS, a tax practitioner must abide by this more rigorous standard. As an illustration, assume that the Internal Revenue Code prescribes the more likely than not test in a particular situation, but the SSTS prescribes the substantial authority standard. Because the more likely than not standard's 50% threshold is higher than the substantial authority standard's easier-to-satisfy 40% threshold, the accountant must apply the tougher more likely than not test.24

Finally, if a tax return position is too weak to meet the requisite reporting standard, what does a taxpayer do? Even if a tax position lacks substantial authority, a taxpayer still may assert it as long as the much lower reasonable basis standard is met and the taxpayer prominently discloses in its tax filing all relevant facts relating to its tax position.25

In summary, as a generalization, tax positions with at least a 40% chance of being upheld usually may be claimed without special disclosures, tax positions with between a 20% and 40% chance of being upheld may be claimed as long as these positions prominently are called to the IRS' attention, and tax positions with less than a 20% chance of success should not be claimed.

If a taxpayer claims a questionable tax position, a tax return preparer must inform the taxpayer about the penalties they may incur and the opportunities they have to avoid penalties by making appropriate tax return disclosures. Preparers who carelessly or willfully commit misconduct by recommending tax return positions that lack adequate authority may incur stiff penalties.26

Claiming Positions That Are Inconsistent with Prior-Year Returns

Under usual circumstances, a taxpayer should treat income and expense items in a consistent manner from year to year. Therefore, for example, if the IRS denied a client's home office deduction claim on last year's tax return, this client generally should refrain from claiming this deduction in subsequent years.

Nonetheless, this consistency rule has several exceptions. As Alice said in Alice in Wonderland, “I can't go back to yesterday because I was a different person then.”27 If circumstances have changed since an earlier period, a taxpayer may assert a previously denied tax position in a later year. Changed circumstances arise in the following situations:

- The taxpayer's position was disallowed in a prior year due to inadequate supporting documentation, but the taxpayer now maintains thorough records

- The taxpayer's position has been approved of in a new court case or IRS pronouncement

- The taxpayer compromised with the taxing authority in a prior year to resolve a minor matter expeditiously, but did not agree with the taxing authority's reasoning28

Completing a Tax Return

At the end of the tax preparation process, a tax return preparer must sign a tax return, attesting that, among other elements, it is complete. This seemingly innocuous requirement poses several issues.

First, a tax return is a summary document that is complete without the inclusion of supporting documentation. Ordinarily, a taxpayer should retain corroborating documentation, such as bank statements and brokerage records, but provide them to taxing authorities only on request.

Second, a tax return generally is not complete unless all nonnumerical questions have been answered. For instance, if an informational question requests a taxpayer's Occupation, a taxpayer generally has a duty to answer this question. Informational questions do not have to be answered, though, if the question is insignificant, inapplicable, confusing, or cannot be answered succinctly.29 For instance, if a state tax return asks a retired, 79-year-old taxpayer to state her occupation, she does not have to answer this inapplicable question.

Correcting Past Tax Returns

It is sometimes said that one should “forgive and forget.” Unfortunately, though, taxing authorities rarely forget or forgive when tax return errors are made.

A tax return preparer's duties do not necessarily end when a tax return is filed. Years later, tax return preparers frequently are requested to perform follow-up work, such as responding to IRS inquiries or correcting inaccuracies in previously filed tax returns.

A tax practitioner's ethical duties concerning erroneous tax returns differ depending on whether the inaccuracy was due to a mistake or an intentional act of deception.

Correcting Unintentional Errors

The impact of an unintentional prior-year tax return error hinges on its significance. Major errors have to be corrected; minor ones do not. Upon discovering a material error in a previously filed tax return, an accountant should inform the taxpayer of the error, the potential consequences, and the recommended corrective action. After being informed about a tax return error, a taxpayer has the ultimate responsibility for filing an amended tax return. If a client refuses to correct an erroneous tax filing, a tax practitioner should consider terminating their professional relationship, but is not compelled to do so.30

If the client relationship survives, a tax practitioner must make sure that the original error is not perpetuated in subsequent years. For instance, if a client in a prior year erroneously capitalized an expenditure into the cost of a factory, the tax practitioner must ensure that factory depreciation on subsequent tax returns is not calculated based on the factory's inflated cost basis.

The presence of a tax return error poses an especially sensitive issue if a tax practitioner, aware of an error, is representing a client in an administrative proceeding, such as a Property Tax Appeals Board hearing. Because a tax practitioner has an absolute duty to be truthful, the tax practitioner should request the client's permission to disclose the error to the administrative tribunal. If the client refuses, the tax practitioner strongly must consider withdrawing as the client's representative.31

Correcting Intentional Misstatements

Upon discovering that a client intentionally filed a false tax return, a tax professional's duties become more extensive. A tax practitioner should inform the client of the penalties associated with filing a fraudulent tax return. However, because tax fraud is a criminal matter, only an attorney should provide legal advice.

Despite the seriousness of the client's conduct, confidentiality duties prevent a tax professional from informing a taxing authority, unless a client grants permission or the law compels disclosure.32

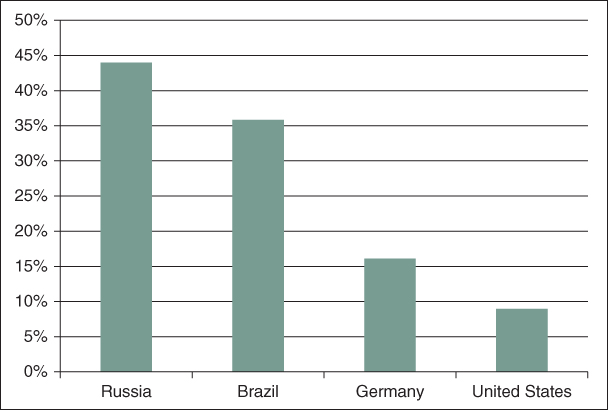

Figure 14-4 Tax Evasion in Selected Countries. (Unreported Income as a Percentage of GNP)34

Completing the Client Engagement

After all requested tasks are completed, a tax practitioner must return all client records to permit the client to fulfill its filing responsibilities. This duty is absolute, even if the client owes unpaid fees to the tax practitioner.35 When fees remain unpaid, though, accountants ordinarily do not have to deliver the finished tax return or other work product that they created, unless the parties' agreement or state law provide otherwise.

Once a client engagement is completed, tax practitioners generally are relieved of all further duties. Accordingly, if a court decision or IRS pronouncement later arises that potentially impacts a client's earlier actions, a tax practitioner is not obligated to provide an update about this subsequent event.

DUTIES AS A TAXPAYER ADVOCATE

As mentioned earlier, tax professionals have both the right and the responsibility to advocate for their clients as long as recommended tax positions comply with established reporting standards. As the former chairman of the AICPA's Committee on Federal Taxation has stated, a tax practitioner is “not expected to approach uncertain tax questions with the same lack of bias that [applies] in expressing an opinion on the fairness of presentation of financial statements.”36

Advocacy has its limits, however.

A tax adviser should never recommend a tax position if it “exploits the audit selection process of a taxing authority.”37 For example, if a tax adviser believes that tax returns that utilize an exact number, such as $100.37, are less likely to be audited than those that appear to display a rounded number, such as $100, the tax adviser should not alter the amounts presented to reduce the likelihood of IRS examination.

Also, a tax adviser should never recommend a tax position to merely create an “arguing point advanced solely to obtain leverage in a negotiation with a tax authority.”38 That is, a tax adviser should never exaggerate its claims or take an unrealistically extreme position in the hope of improving its bargaining position. As an illustration, assume that a state tax agency believes that all 90 of a trucking company's drivers should be classified as employees for payroll tax purposes, but the company's owner sincerely believes that only 65 of these drivers should be considered employees. The tax adviser should not make the unwarranted claim that none of the drivers are employees in the hope of negotiating a compromise that is split down the middle at, say, 45 employees.

DUTIES AS A TAX PLANNER

Tax practitioners often are asked to give clients advice, but not necessarily prepare their tax return. This advice sometimes concerns the tax impact of a previously consummated transaction, and on other occasions, it involves structuring and implementing a proposed transaction.

In rendering advice about an actual or contemplated transaction, a practitioner should follow five steps.

First, a tax adviser should understand the relevant background facts. These facts can be gathered from the client, the client's representative, or a third party who is promoting or entering into the transaction.

Next, a tax adviser should evaluate whether assumptions underlying the transaction are reasonable. Overly optimistic or simplistic assumptions should be challenged and clarified.

Third, a tax adviser should apply relevant sources of tax authority to the facts. Even a small difference between elements of a client's proposed transaction and the factual pattern presented in a prior court decision or published IRS ruling may alter the resulting tax consequences.

Additionally, a tax adviser should consider whether a transaction complies only with the letter of the law, but not with the spirit. Taxing authorities often apply the substance over form doctrine to disallow transactions that lack economic substance. For example, if a parent supposedly loans money to an adult child but never charges interest or demands repayment, the IRS will not hesitate to recharacterize this supposed loan as a gift and subject it to possible gift taxes.

The IRS also may disallow transactions that lack a good faith nontax business purpose or integrate a set of seemingly legitimate steps into an implausible step transaction. To illustrate, assume that a company sells land at a loss to a real estate broker and then the broker sells the land right back to the company for the same price. Although the first sale standing alone appears to result in a deductible tax loss, the end result of these two integrated transactions was a round trip that lacked economic substance. As a result, because only the illusion of a loss was created, the IRS would disallow an attempted loss write-off.

Finally, a tax adviser should reach a well-reasoned conclusion. This conclusion should include an assessment of the likelihood that a taxing authority will examine the transaction, challenge it, and impose penalties. If various alternatives are feasible, each alternative should be carefully considered. Oral recommendations are permitted, but written recommendations are preferable, especially when a transaction is complex.39

GENERAL PROFESSIONAL DUTIES

CPAs are subject to all the broader principles and rules established by the Code of Conduct, in addition to the SSTS and other tax-oriented pronouncements. Therefore, like all accounting professionals, tax practitioners must maintain the highest standards of honesty, integrity, and objectivity, always remaining free of conflicts of interest and preserving client confidentiality.

THE TAXPAYER'S DUTIES

Under our system of taxation, taxpayers have the final responsibility for ensuring that their tax returns are accurate and for correcting errors in previously filed tax returns. An accountant merely prepares a tax return based on taxpayer representations and provides guidance to clients about their responsibilities.

When a taxing authority imposes additional taxes upon discovering inaccuracies in a tax return, clients sometimes blame their accountant, insisting that the accountant bear the cost of the additional taxes owed. These attempts typically are unsuccessful, however, because a client has the ultimate responsibility for the principal amount of tax that should have been paid originally. However, if an accountant's carelessness causes incremental harm to a client beyond the principal amount of tax owed, the accountant is responsible for these so-called consequential damages. Consequential damages usually are limited to the additional penalties and loss of interest that result from an accountant's misconduct.

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRUTHFUL TAX REPORTING

To encourage candid and accurate tax reporting, taxpayers generally cannot be compelled to reveal their tax returns to others beside the taxing authority.

Nonetheless, for individuals and unaudited small businesses, income tax returns provide a convenient and comprehensive portrait of their annual earnings activities. As a result, truthful tax reporting is essential because taxpayers often utilize their tax returns for purposes wholly unrelated to tax collection. For instance, prospective homebuyers submit tax returns to banks in conjunction with loan applications, tenants submit tax returns to commercial landlords to demonstrate their creditworthiness, and sellers of small businesses demonstrate their operating results by providing tax returns to prospective buyers.

Because tax returns are unaudited, sophisticated businesspeople sometimes are concerned about whether a purported tax return is authentic. To assuage this concern, the IRS will directly provide lenders and others with an official copy of a taxpayer's previously filed returns upon receiving a taxpayer's written authorization.40

EXERCISES

The Scope of Tax Standards

- A corporate client incurred substantial penalties for understating its tax liability. As a result, it has accused its tax return preparer in a lawsuit of acting “below the standard of care” and “recklessly” for failing to apply the substantial authority standard in preparing this client's tax return. In support of its claims, the client's attorney has pointed out to the jury that AICPA Standards generally require that a tax position meet the substantial authority standard. The client is suing to recover the penalties imposed by the taxing authority as damages. The tax law did not establish any particular standard of reporting regarding this taxpayer's tax positions.

- Can the tax return preparer successfully defend this lawsuit by pointing out that she is not a CPA?

- If this tax return preparer was a CPA, could she successfully defend this lawsuit by pointing out that she is not a member of the AICPA?

- Does a tax position always have to meet, at minimum, the substantial authority standard?

Tax Return Preparer's Duties

- Your client has given you a list stating that her charitable contributions were $20,000 last year. This amount would constitute nearly 10% of her take-home pay. It also is a larger percentage of income than you customarily see clients giving to charity. Do you have a duty to verify the accuracy of this charitable deduction?

- Your client has given you a list stating that her charitable contributions were $90,000 last year. This amount is more than her take-home pay last year. Do you have a duty to verify the accuracy of this charitable deduction?

- You have prepared tax returns for Christine and Henry Chang for several years. This year, they emailed you, stating that they have finalized their divorce but they “remained friendly” and want you to prepare each of their individual tax returns. They did insist, however, that each's financial affairs be kept confidential from the other.

When Christine brought in her tax records, she listed all three of her children as dependents and provided information showing that they attended school in her neighborhood, which is about 40 miles from where Henry lives. Christine's oldest son, John, is 17 years old. Christine provided you with a photocopy of his driver's license, which shows his address as being Christine's residence. Accordingly, you filed Christine's tax return, claiming all three children as her dependents.

When Henry brought in his tax records, he also listed all three children as his dependents. He brought in a copy of their divorce decree. In a signed document incorporated into this decree, Christine expressly waived her right to claim their children as dependents on her tax return, in exchange for her receiving increased alimony.

Based on your online research, the custodial parent who has physical custody of the children a majority of the time generally is entitled to claim children as dependents unless the right to this dependency exemption has been transferred by a signed writing to the noncustodial parent.

- When you prepare Henry's tax return, may he claim the three children as dependents on his individual tax return?

- What, if anything, should you tell Christine?

- What, if anything, should you tell the IRS?

- Your client qualifies for Head of Household filing status rather than Single status. Head of Household tax rates are lower than the Single tax rates. However, you read that Head of Household rates have a higher IRS audit rate and, after sharing this observation with your client, he has chosen to file as Single.

- If your client qualifies as Head of Household, may you report his filing status as Single?

- Do you have any reasonable speculation about why your client preferred to file as Single?

- During the course of reviewing a client's tax returns for earlier years, you noticed that his reported interest income dropped off substantially this year from prior years. You also did not notice any sales of bonds reported by your client this year, and interest rates have been steady over the past few years. Your client did not ask you to review his prior tax returns. Do you have a duty to ask your client to explain why his interest income changed so much?

Your client is disabled and unable to work. However, the state tax form he is about to file asks for a taxpayer's Trade or Business. How should you answer that question?

- Your client is a well-known fashion designer who has created three successful Internet brands. Each online brand sells a different genre of clothing, and each is profitable. This past year, your client boasted that she “got great pleasure” out of creating a fourth, innovative retail clothing brand. This brand was professionally managed and well capitalized, but it unfortunately generated a large loss due to a lack of customers. Your client wants to deduct all of the expenses incurred by this brand on her tax return, but she has heard that personal expenses may not be claimed and she admits that she got great personal joy out of starting this business. May your client claim all of these expenses?

- In preparing an estate tax return, you listed the deceased's total assets at $2.7 million. This is the amount that the executor of the deceased's estate told you was proper. The executor is the deceased's nephew and, for tax purposes, he is considered to be your client. He also is a major beneficiary of the deceased's will.

The IRS now has selected this estate tax return for examination. Further discussions with the executor reveal that $400,000 of assets were not reported. You have told the executor that you would like to inform the IRS about this omission and correct it. The executor has refused to allow you to do so. What should you do?

The Use of Estimates

- A computer virus destroyed all of your client's files concerning depreciation expense and fixed assets. All other tax records for this manufacturing client remain intact. How should you report depreciation on this client's tax return?

- “Snakeman” Jackson, as his friends call him, is an aging blues guitarist and songwriter. He frequently tours throughout Europe and South America. He requires tour promoters to pay him half of his fee upfront. He then collects the other half of his fee in cash from the performance venue immediately following the performance. He told you that he collects in cash because “once you're gone, they forget you.”

“Snakeman” is a great guitarist, but not a great accountant. He maintains meticulous records of his gigs, including bank deposits, receipts, and copies of his contracts. He pays his backup musicians and roadies in cash, but always gets signed receipts from them. However, he pays for his hotels in cash, and usually checks out quickly without saving his receipts. He explained to you that he does this because, once he has collected in cash for a performance, he wants to minimize the amount of cash he physically carries with him to the next location.

It is clear to you from your client's website that he did in fact perform last year at over 80 venues throughout the world. How should you report the hotel expenses on Snakeman's tax return?

Tax Reporting Standards

- Which of the following reporting standards is higher:

- Substantial Authority versus Reasonable Basis?

- Realistic Possibility of Success versus More Likely Than Not?

- Reasonable Basis versus Realistic Possibility of Success?

- Substantial authority versus More Likely Than Not?

- Assume that the tax law does not prescribe a reporting standard for a particular tax position.

- What threshold standard should a tax return preparer apply to avoid penalties?

- What is the lowest threshold standard for asserting a tax position if the taxpayer is willing to disclose his use of such a standard?

- Assume that the tax law does prescribe a reporting standard for a particular tax position. What threshold standard should a tax return preparer apply to avoid penalties?

- After consulting with a tax adviser, a taxpayer believes that the odds of her state income tax return being audited are 80%. If audited, she believes that the odds of the state taxing authorities detecting and disallowing a certain deduction claim are 80%. If the state authorities disallow this deduction claim, she objectively believes that there is a 30% chance that a state tax court will overturn the state taxing authority's decision and allow this deduction.

- What is the probability that she in fact will ultimately get the benefit of this deduction on her tax return?

- May she claim this deduction, without making special disclosures?

Completing the Reporting Process

- Your client sold stock for $3,059 this year. Her brokerage fees on the sale were $19. The tax schedule for reporting capital gains asks for the Amount Realized, which equals the gross selling price, net of direct selling costs. Accordingly, your client reported the Amount Realized as $3,040. Your client did not submit her brokerage statement as a supplemental schedule to her tax return to corroborate the stock's selling price or the amount of her brokerage fees. Was your client's tax return filed properly?

Duties as a Tax Planner

- Your client operates a small telemarketing company out of her home, and she has one full-time employee who assists in making phone calls to prospective customers. Her teenage daughter also enters data into the company's electronic record-keeping system on a regular basis. Her daughter is somewhat “spoiled,” so your client pays her $40 cash per hour to encourage her to develop a solid work ethic and work diligently. Your client has told you that she wants to “be straight” with the IRS in every way. Are there any issues that you might want to challenge or research?

- Your client owns a 3-bedroom home with a 2-car garage in a suburb of Tucson, Arizona. Although the home office rules are strict on deducting expenses, you have determined that your client satisfies these rules. Her home office occupies the spare bedroom in her home, and it comprises about 480 square feet of her 2,400 square foot home. The garage is an additional 480 square feet.

Your client is interested in claiming the maximum allowable deductions for her home office. In reviewing your client's tax return for last year, you noticed that she claimed a deduction equal to the full amount of her mortgage payment on the house. Your client did not, however, deduct any other expenses associated with her home office. She did not maintain detailed records and was concerned that the IRS might think that she was exaggerating her other expenses if she just “ballparked them” without adequate supporting documentation.

- Are there any issues that you want to challenge or research?

- Should you inform the tax return preparer who filed her return last year about these errors?

- What other advice should you give to your client?

- Assume that the prior-year tax return preparer is a friend of yours, but he really screwed up and should compensate your client if she incurs tax penalties and interest. Would you inform your client about her rights against your friend? Should you inform your friend about this?

Taxpayer's Duties

- Kupan, a famous forensic pathologist, failed to report income from the sale of his mansion on his tax return. His gain on sale exceeded $1.7 million. He also sold stock at a $400,000 gain and did not report that gain either.

In a criminal prosecution against Kupan for tax fraud, Kupan blamed his accountant, Rachel, for the omission, claiming that Rachel knew that the pathologist was a “poor record-keeper.” Kupan admitted that he read the tax return prepared by Rachel and signed it. Will Kupan's defense of shifting responsibility to Rachel in this criminal prosecution be successful?

Comprehensive Problems

- You are a licensed CPA who is a member of both the AICPA and the Oregon Society of CPAs. You work in the Tax Compliance Department of a major publicly traded supermarket chain. The company is considering whether to claim a deduction for food donated to various homeless shelters. According to Internal Revenue Code Section 170(b), “in the case of a corporation, the total deductions under subsection (a) for any taxable year shall not exceed 10 percent of the taxpayer's taxable income,” computed without regard to certain deductions.

Based on your calculations, your employer has already exceeded this limit and cannot claim any deduction for the donated food if it considers the donation to be a charitable contribution. However, this donation earns the company positive news coverage and publicity. As a result, several of your colleagues believe that a full deduction may be claimed under the Tax Code's provisions that allow ordinary and necessary business expenses, such as marketing and advertising, to be claimed.

Your supervisor has asked you to assume that this deduction will save your company $1 million in taxes if it not disallowed by the IRS. You also have been asked to assume that the chance of this item being challenged by the IRS if the company places it on its tax return is 1 in 10, and the probability of the company successfully persuading the IRS about the correctness of its tax position is about 2 in 10. If challenged and your company fails to persuade the IRS that your claimed deduction is allowable, the penalty will be $10 million, on average. Your client is not willing to call attention to this tax position by making any special tax return disclosures.

- Are you personally obligated to abide by the AICPA's Statement of Standards for Tax Services, even though you do not work in public practice?

- Assume that you are not bound by the AICPA Standards. Would it be a rational economic decision for your client to claim these food donations as fully deductible under the Tax Code's ordinary and necessary rules?

- Assume that you are bound by the AICPA Standards. Can you advise your client to claim these food donations as an ordinary and necessary expense?

- Could your client claim this deduction if it was willing to make explicit disclosures about this deduction and attach that disclosure to its tax return?

- Joe Bettalia, a general contractor, has struggled in recent years due to a downturn in the construction market in his region of the country.

During the past two years, Joe has failed to file tax returns. He now has come to your office and asked you to file a tax return for the current year. You have agreed to do so. Joe also made an unusual request. He has asked you to deliberately overstate his income and tax liability on this year's return. When you expressed surprise at his request, he told you that “he feels guilty about not having filed with the government” in recent years. Also, he told you that his father never has “shown him much respect,” so he wants to leave a tax return that shows high income around the house, where his father will see it. “That way, my Dad will think I'm a success and show me at least some of the respect that I'm owed.”

May you intentionally prepare a tax return for Joe that overstates his income and related tax liability?

- Your client is the former lead singer of a famous rock band. He is retired now, but he has numerous financial planning, investment, and tax concerns, and he has retained you as his accountant and financial adviser. When he first hired you, he wanted to know if you would be “around for the long haul” because he was “fed up” with managers, lawyers, and other advisers who frequently were irresponsible and left him in difficult situations. You assured him that you are dependable and loyal.

Over the years, he has been a great client. He has interesting problems, he has referred other clients to you, he always pays your fees on time, and he even has invited you to fun social events and parties where other famous entertainers have mingled with you. In the past few months, however, you have been concerned about his behavior. He seems to be depressed, and you saw him screaming loudly and rudely at his business manager. During that incident, he raised his fist and appeared to be threatening to hit her. However, he did not do so.

- What should you do?

- Assume that you have decided to withdraw from providing services to this client. One year later, however, your client receives an inquiry from the IRS about a tax return that you had prepared several years ago for this client. As the tax return preparer for the tax year under IRS examination, you uniquely are qualified to respond to the IRS's inquiry letter and, if needed, represent your client in an audit examination of his tax return. Should you agree to represent this client for this limited purpose?

- Given the ill will between the client and you when you withdrew, would it be appropriate for you to ask for a retainer in advance of providing him with taxpayer representation, even though you had never required a retainer fee before?

- Your client has a blood type that is so rare and in demand that she earns $300 each time she provides blood. Last year, she earned a total of $15,000 from giving blood. Your client has substantial capital loss carryforwards from stock sales entered into last year. Your client has asked you if the money she receives from selling blood constitutes the sale of an asset or the provision of a service.

- From a federal income tax standpoint, would your client prefer to contend that she is selling an asset or providing a service?

- Under the AICPA Standards, what steps should you take to determine whether your client can claim her income as a capital gain?

- From a state sales tax standpoint, would your client prefer to contend that she is selling an asset or providing a service?

- Do the AICPA Standards apply to the preparation of state sales tax returns?

- Your client has asked you to report her proceeds as the sale of an asset for federal income tax purposes, but as the provision of a service for state sales tax purposes. Is this definitely unethical?