Chapter 3

Dressing Up Your Data Tables

In This Chapter

![]() The principles of table design

The principles of table design

![]() Custom number formatting

Custom number formatting

![]() Applying custom format colors

Applying custom format colors

![]() Applying custom format conditions

Applying custom format conditions

The Excel table is the perfect way to consolidate and relay information. Data tables are quite common — you’ll find one in any Excel report. Yet the concept of making tables easier to read and more visually appealing escapes most of us.

Maybe it’s because the nicely structured rows and columns of a table lull us into believing that the data is already presented in the best way possible. Maybe the options of adding color and borders make the table seem nicely packaged. Excel makes table creation easy, but even so, you can use several design principles to make your Excel table a more effective platform for conveying your data.

In this chapter, you explore how easy it is to apply a handful of table design best practices. The tips found here ultimately help you create visually appealing tables that make the data within them easier to consume and comprehend.

Table Design Principles

Table design is one of the most underestimated endeavors in Excel reporting. How a table is designed has a direct effect on how well an audience absorbs and interprets the data in that table. Unfortunately, putting together a data table with an eye for economy and ease of consumption is an uncommon skill.

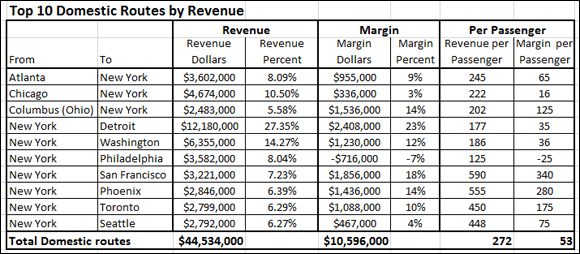

For example, the table shown in Figure 3-1 is similar to many found in Excel reports. The thick borders, the variety of colors, and the poorly formatted numbers are all unfortunate trademarks of tables that come from the average Excel analyst.

Figure 3-1: A poorly designed table.

Throughout this chapter, you improve on this table by applying these four basic design principles:

- Use colors sparingly, reserving them only for information about key data points.

- De-emphasize borders, using the natural white space between the components to partition your dashboard.

- Use effective number formatting to avoid inundating your table with too much ink.

- Subdue your labels and headers.

Use colors sparingly

Color is most often used to separate the various sections of a table. The basic idea is that the colors applied to a table suggest the relationship between the rows and columns. The problem is that colors often distract and draw attention away from the important data. In addition, printed tables with dark-colored cells are notoriously difficult to read (especially on black-and-white printers). They are also hard on the toner budget, if that holds any importance to you.

Colors in general should be used sparingly, reserved for providing information about key data points. The headers, labels, and natural structure of your table are more than enough to guide your audience. There is no real need to add a layer of color as demarcation for your rows and columns.

Figure 3-2 shows the table from Figure 3-1 with the colors removed. As you can see, it’s already easier to read.

Figure 3-2: Remove unnecessary cell coloring.

Figure 3-3: Use the No Fill option to clear cell colors.

De-emphasize borders

Believe it or not, borders get in the way of quickly reading the data in a table. Because borders help separate data in nicely partitioned sections, this may seem counterintuitive, but the reality is that a table’s borders are the first thing your eyes see when you look at a table. Don’t believe it? Stand back a bit from an Excel table and squint. The borders will come popping out at you.

You should always endeavor to de-emphasize borders and gridlines wherever you can. Try to use the natural white space between the columns to partition sections. If borders are necessary, format them to lighter hues than your data; light grays are typically ideal. The idea is to indicate sections without distracting from the information displayed.

Figure 3-4 demonstrates these concepts with the table from Figure 3-1. Notice how the numbers are no longer caged in gridlines and that headings now jump out at you with the addition of Single Accounting underlines.

Figure 3-4: Minimize the use of borders and use the single accounting underlines to accent the column headers.

You can format borders by first highlighting the cells you are working with, right-clicking to bring up the contextual menu, and then selecting the Format Cells option. This will activate the Format Cells dialog box shown in Figure 3-5. From here, take the following steps:

-

Select an appropriate line thickness.

Typically, you should select the line with the lightest weight.

-

Select an appropriate color.

Again, lighter hues are the best options.

- Use the border buttons to control where the borders are placed.

Figure 3-5: Use the Border tab of the Format Cells dialog box to customize your borders.

To apply the single accounting underline, right-click the column headings and select Format Cells. Click the Font tab of the Format Cells dialog box and in the Underline drop-down menu, choose the Single Accounting option, as demonstrated in Figure 3-6.

Figure 3-6: Single accounting underlines effectively call out your column headers.

Use effective number formatting

Every piece of information in your table should have a reason for being there. In an effort to clarify, tables often inundate the audience with superfluous ink that doesn’t add value to the information. For example, you’ll often see tables that show a number like $145.57 when a simple 145 would be just fine. Why include the extra decimal places, which serve only to add to the mass of numbers that the audience has to plow through?

Here are some guidelines to keep in mind when applying formats to the numbers in the table:

- Use decimal places only if that level of precision is required.

- In percentages, use only the minimum number of decimals required to represent the data effectively.

- Rather than use currency symbols (like $ or £), let labels clarify that you are referring to monetary values.

- Format very large numbers to the thousands or millions place.

- Right-align numbers so that they are easier to read and compare.

Figure 3-7 shows the table from Figure 3-1 with appropriate number formatting applied. Notice that the large revenue and margin dollar amounts have been converted to the thousands place. In addition, the labels above the numbers now clearly indicate as such.

Figure 3-7: Use number formatting to eliminate clutter in the table and draw attention to key metrics.

The percentages have been truncated to show no decimal places. Also, the color coding draws attention to the Margin % column, the key metric in this table.

Amazingly, all of these improvements have been made simply with number formatting. That’s right: No formulas were used to convert large numbers to the thousands place, no conditional formatting was used to color code the Margin % field, and there were no other peripheral tricks of any kind.

Subdue your labels and headers

No one would argue that the labels and headers of a table aren’t important. On the contrary, they provide the audience with the guidance and structure needed to make sense of the data within. However, many of us have a habit of overemphasizing labels and headers to the point that they overshadow the data within the table. How many times have you seen a bold or oversized font applied to headers? The reality is that your audience will benefit more with subdued labels.

De-emphasizing labels by formatting them to lighter hues actually makes the table easier to read and draws more attention to the data within the table. Lightly colored labels give users the information they need without distracting them from the information being presented. Ideal colors to use for labels are soft grays, light browns, soft blues, and greens.

Font size and alignment also factor into the effective display of tables. Aligning column headers to the same alignment as the numbers beneath them helps reinforce the column structures in your table. Keeping the font size of your labels close to that of the data within the table helps keep your eyes focused on the data — not the labels.

Figure 3-8 illustrates how the original table from Figure 3-1 looks with subdued headers and labels. Note how the data now becomes the focus while the muted labels work in the background.

Figure 3-8: Send your labels and headers to the background by subduing their colors and keeping their font sizes in line with the data.

Figure 3-9 illustrates the difference these simple improvements can make in the readability of your data tables. It’s easy to see how a few table design principles can greatly enhance your ability to present table-driven data.

Figure 3-9: Before and after applying table design principles.

Getting Fancy with Custom Number Formatting

You can apply number formatting to cells in several ways. Most people simply use the convenient number commands found on the Home tab. By using these commands, you can quickly apply some default formatting (number, percent, currency, and so on) and just be done with it, but a better way is to use the Format Cells dialog box, in which you have the ability to create your own custom number formatting.

Number formatting basics

Follow these steps to apply basic number formatting:

-

Right-click a range of cells and select Format Cells from the menu that appears.

The Format Cells dialog box appears.

-

Open the Number tab and choose a starting format that makes the most sense for your scenario.

In Figure 3-10, the format chosen is Number and the selected options are to use a comma separator, to include no decimal places, and to enclose negative numbers in parentheses.

-

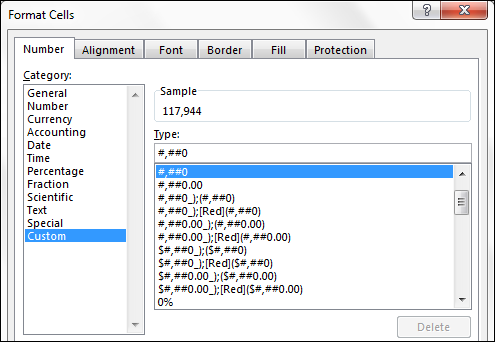

Click the Custom option, as shown in Figure 3-11.

Excel takes you to a screen that exposes the syntax that makes up the format you selected. Here, you can edit the syntax in the Type input box to customize the number format.

Figure 3-10: Choose a base format.

Figure 3-11: The Type input box allows you to customize the syntax for the number format.

The number formatting syntax tells Excel how a number should look in various scenarios. Number formatting syntax consists of different individual number formats separated by semicolons.

In this case, you see

#,##0_);(#,##0)

Here, you see two different formats: the format to the left of the semicolon and the format to the right of the semicolon.

By default, any formatting to the left of the first semicolon is applied to positive numbers and any formatting to the right of the first semicolon is applied to negative numbers. So with this choice, positive numbers will be formatted as a simple number, whereas negative numbers will be formatted with parentheses, like this:

(1,890) 1,982

You can edit the syntax in the Type input box so that the numbers are formatted differently. For example, try changing the syntax to

+#,##0;-#,##0

When this syntax is applied, positive numbers will start with the + symbol and negative numbers will start with the – symbol, like so:

+1,200-15,000

This comes in handy when formatting percentages. For instance, you can apply a custom percent format by entering the following syntax into the Type input box:

+0%;-0%

This syntax gives you percentages that look like this:

+43%-54%

You can get fancy and wrap your negative percentages with parentheses with this syntax:

0%_);(0%)

This syntax gives you percentages that look like this:

43%(54%)

Formatting numbers in thousands and millions

Earlier in this chapter, you format your revenue numbers to appear in thousands. This allows you to present cleaner numbers and avoid inundating the audience with overlarge numbers. To show your numbers in thousands, highlight them, right-click, and select Format Cells from the menu that appears.

After the Format Cells dialog box opens, click the Custom option to get to the screen shown in Figure 3-12.

Figure 3-12: Go to the Custom screen of the Format Cells dialog box.

In the Type input box, add a comma after the format syntax:

#,##0,

After confirming your changes, your numbers will automatically appear in the thousands place!

The beautiful thing here is that this technique doesn’t change the integrity or truncate the numeric values in any way. Excel is simply applying a cosmetic effect to the number. To see what this means, take a look at Figure 3-13.

Figure 3-13: Formatting numbers applies only a cosmetic look. Look on the formula bar to see the real, unformatted number.

The selected cell has been formatted to show in thousands; you see 118. But if you look on the formula bar above it, you’ll see the real unformatted number (117943.605787004). The 118 you are seeing in the cell is a cosmetically formatted version of the real number shown on the formula bar.

If needed, you can even indicate that the number is in thousands by adding “k” to the number syntax:

#,##0,"k"

This would show your numbers like this:

118k318k

You can use this technique on both positive and negative numbers:

#,##0,"k"; (#,##0,"k")

After applying this syntax, your negative numbers also appear in thousands:

118k(318k)

Need to show numbers in millions? Easy. Simply add two commas to the number format syntax in the Type input box:

#,##0.00,, "m"

Note the use of the extra decimal places (.00). When converting numbers to millions, it’s often useful to show additional precision points, as in

24.65 m

Hiding and suppressing zeroes

In addition to formatting positive and negative numbers, Excel allows you to provide a format for zeroes. You do this by adding another semicolon to your custom number syntax. By default, any format syntax placed after the second semicolon is applied to any number that evaluates to zero.

For example, the following syntax applies a format that shows n/a for any cells that contain zeroes:

#,##0_);(#,##0);"n/a"

You can also use this to suppress zeroes entirely. If you add the second semicolon but don’t follow it with any syntax, cells containing zeroes will appear blank:

#,##0_);(#,##0);

Again, custom number formatting only affects the cosmetic look of the cell. The actual data in the cell is not affected. Figure 3-14 demonstrates this. The selected cell is formatted so that zeroes appear as n/a, but if you look at the formula bar, you can see the actual unformatted cell contents.

Figure 3-14: Custom number formatting that shows zeroes as n/a.

Applying custom format colors

Have you ever set the formatting on a cell so that negative numbers appear in red? If you have, you essentially applied a custom format color. In addition to controlling the look of your numbers with custom number formatting, you can control their color.

In this example, you format the percentages so that positive percentages appear blue with a + symbol, whereas negative percentages appear red with a – symbol. Enter this syntax in the Type input box shown in Figure 3-11:

[Blue]+0%;[Red]-0%

Notice that all it takes to apply a color is to enter the color name wrapped in square brackets [ ].

Now, there are only certain colors — the eight Visual Basic colors — you can call out by name like this. These colors make up the first eight colors of the default Excel color palette:

- [Black]

- [Blue]

- [Cyan]

- [Green]

- [Magenta]

- [Red]

- [White]

- [Yellow]

Formatting dates and times

Custom number formatting isn’t just for numbers. You can also format dates and times. As you can see in Figure 3-15, you use the same dialog box to apply date and time formats using the Type input box.

Figure 3-15: Dates and times can also be formatted using the Format Cells dialog box.

Figure 3-15 demonstrates that date and time formatting involves little more than stringing together date-specific or time-specific syntax. The syntax used is fairly intuitive. For example, ddd is the syntax for the 3-letter day, mmm is the syntax for the 3-letter month, and yyyy is the syntax for the 4-digit year.

There are several variations on the format for days, months, years, hours, and minutes. It’s worthwhile to take some time and experiment with different combinations of syntax strings.

Table 3-1 lists some common date and time format codes you can use as starter syntax for your reports and dashboards.

Table 3-1 Common Date and Time Format Codes

|

Format Code |

1/31/2014 7:42:53 PM Displays As |

|

M |

1 |

|

Mm |

01 |

|

mmm |

Jan |

|

mmmm |

January |

|

mmmmm |

J |

|

dd |

31 |

|

ddd |

Thu |

|

dddd |

Thursday |

|

Yy |

14 |

|

yyyy |

2014 |

|

mmm-yy |

Jan-14 |

|

dd/mm/yyyy |

31/01/2014 |

|

dddd mmm yyyy |

Thursday Jan 2014 |

|

mm-dd-yyyy h:mm AM/PM |

01-31-2014 7:42 PM |

|

h AM/PM |

7 PM |

|

h:mm AM/PM |

7:42 PM |

|

h:mm:ss AM/PM |

7:42:53 PM |

If you’re working with a table that contains colored cells, you can quickly remove the color by highlighting the cells and choosing the No Fill option under the Theme Colors drop-down menu on the Home tab. See

If you’re working with a table that contains colored cells, you can quickly remove the color by highlighting the cells and choosing the No Fill option under the Theme Colors drop-down menu on the Home tab. See  Note that the syntax for the positive formatting in the previous example ends with an underscore and a closing parenthesis:

Note that the syntax for the positive formatting in the previous example ends with an underscore and a closing parenthesis: