CHAPTER 4

Capital Adequacy for Islamic Banks: A Survey

Capital isn't scarce; vision is

—Sam Walton

Financial liberalisation, as part of globalisation, has been followed keenly by developing countries since the 1990s. Several restrictions were eased, and self-regulation was considered to be the motivating factor. However, developments show that everything did not work well. There were several instances of malpractice, financial frauds and some failures. In responding to this, regulators started looking at the existing set of standards and ways to overcome the issue of balancing control and freedom. From simple capital provisions to comprehensive frameworks for risk management, the practice of risk management, as a result, has undergone wholesale transformation over the past two decades (Akkizidis and Khandelwal, 2007). More systematic transformation has taken place during the current straitened times. It is a fact that each country has its own set of regulations based on several parameters. The most common among them is the requirement to hold minimum capital indexed to the activities of the bank.

Capital adequacy is at the core of supervisory activities all over the world. It is an important benchmark for the soundness of financial institutions. It is gaining more prominence after the recent credit crunch, which saw numerous financial institutions collapsing because their capital was not big enough to absorb the risks they were taking. Developments have shown that the market turmoil turned out to be deeper and more enduring than previously anticipated and that financial markets are failing to sustain the normal flow of capital. Regulators, banks and industry participants realised that capital is a critical factor for the intrinsic strength of banks. Therefore, this chapter is designated to discuss capital adequacy in Islamic banking, which is explored empirically in the following chapters with the opinions of sample bankers, financiers, Shari'ah scholars and academics.

The fundamental principle that capital is the currency of risk and that adequate capital protects against distress applies equally to all banks. Therefore, the implementation of Basel II is as critical to Islamic banks as it is to their conventional counterparts. With necessary adjustments, the three Pillars of Basel II could be applicable to Islamic banks. The need for supervisory oversight in Pillar 2 can hardly be overemphasised, as market discipline through disclosure will provide greater transparency and benefit to Islamic banks. The capital treatment of Profit-Sharing Investment Accounts (PSIAs) adds complexity to capital requirements for Islamic banks. Notwithstanding the loss-absorbing features of PSIAs, in practice they behave like normal deposits and most regulators do not treat them as having capital features. Hence, the risk-sharing characteristic of PSIAs requires special capital treatment.

The previous two chapters have dealt with the evolution of Islamic banking and the major types of risks in conventional and Islamic banks. The present chapter provides a brief review of the Basel II Accord and is hence largely based on documents issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS). A brief summary of the original Basel I Accord is presented, highlighting the major limitations of the first Accord. A summary of the three Pillars of Basel II and the forthcoming Basel III standards and their applicability for Islamic financial institutions (IFIs) is also presented. The Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) has issued capital adequacy standards for the Islamic financial industry, which are discussed in detail. This chapter, however, does not thoroughly discuss Basel II, nor does it examine every single detail of the IFSB papers, as plenty of literature exists about the Basel Accords and other Bank for International Settlements (BIS) guidelines, and the IFSB papers are brief and simple enough to be self-explanatory. This chapter highlights the specifics of capital adequacy requirements for IFIs, explains the differences between the conventional Basel Accords and the Islamic version provided by the IFSB, and illustrates how the capital adequacy requirement can be used as a tool for risk mitigation for Islamic banks.

SIGNIFICANCE OF CAPITAL IN BANKING

Nearly all jurisdictions with active banking markets require banks to maintain a minimum level of capital. Capital plays an important role in any business but it is critically important in the case of banks, as it serves as a foundation for a bank's future growth and as a cushion against its unexpected losses. Adequately capitalised banks as well-managed banks are better able to withstand losses and to provide credit to consumers and businesses alike throughout the business cycle, particularly during downturns. Hence, capital is one of the key determinants and indicators of the soundness of a bank, not only because adequate capital serves as a safety net, but also because it is the ultimate determinant of a bank's lending and investment capacity. Adequate levels of capital thereby help to promote public confidence in the banking system.

Banks by the nature of their business have a lower capital-to-liabilities ratio than other types of business. This low ratio is a reflection of the nature of the intermediation business and acceptance of large amounts of liabilities in the form of deposits. To encourage prudent management of the risks associated with the unique balance sheet structure, regulators require banks to maintain a certain level of capital. The idea behind such a requirement is that a bank's balance sheet should not be expanded beyond the level of risks its capital can absorb. The technical challenge, however, for both banks and supervisors, has been to determine how much capital is necessary to serve as a sufficient buffer against unexpected losses. If capital levels are too low, banks may be unable to absorb high levels of losses. On the other hand, excessively low levels of capital increase the risk of bank failures which, in turn, may put depositors' funds at risk. Under-capitalised banks are highly prone to the risk of insolvency and can also suffer from retarded growth. If capital levels are too high, banks may not be able to make the most efficient use of their resources. A bank which is over-capitalised will have low return on its capital and will not be able to pay decent dividends to its shareholders (Jorion and Khoury, 1996). Thus, arriving at an optimal level of capital is in the best interest of banks and shareholders. Both financial intermediaries and regulators are therefore sensitive to the dual role of capital. Financial intermediaries tend to focus more on the earnings-generating role, while regulators tend to be focused on the stability-cushion role.

CLASSIFICATION OF CAPITAL

Defining what constitutes capital is a long-debated issue. However, there is a wide acceptance of the capital structure that has been stipulated by the BCBS, which segregates capital into three categories as set out in Table 4.1.

TABLE 4.1 Classification of capital in the Basel Accords

Source: Adapted from Greuning and Iqbal (2008:223)

| Classification | Contents |

| Tier 1 (core capital) | Ordinary paid-up share of capital or common stock, disclosed reserves from post-tax retained earnings, non-cumulative perpetual preferred stock (goodwill to be deducted) |

| Tier 2 (supplementary capital) | Undisclosed reserves, asset revaluation reserves, general provisions or general loan-loss provisions, hybrid (debt-equity) capital instruments and subordinated term debts |

| Tier 3 | Unsecured debt: subordinated and fully paid up, to have an original maturity of at least two years and not be repayable before the agreed repayment date unless the supervisory authority agrees |

In general, according to BCBS (2006), the capital of a bank should have three important characteristics:

- It must be permanent;

- It must not impose mandatory fixed charges against earnings; and

- It must allow for legal subordination to the rights of depositors and other creditors.

STEPS IN THE BASEL ACCORD

One cannot discuss capital adequacy without mentioning the renowned Basel Accord. The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) was established on 17 May 1930; it is the oldest international financial institution. It provides a platform for consultative cooperation among the central banks. The role of BIS has undergone change as per the needs of the international financial sector. BIS now also acts as an institution for collection, compilation and dissemination of economic and financial statistics. It actively promotes global financial stability, and also performs the traditional banking function for the central bank community (gold and foreign exchange transactions). It has several committees working on different aspects of international financial stability. The BCBS, as part of the BIS structure, was formed at the end of 1974 by the Governors of the G10 nations. The BCBS issued a series of documents beginning in 1975 on banking supervision (Akkizidis and Khandelwal, 2007).

The Basel I Accord

The 1988 Basel Capital Accord set out the first internationally accepted definition of, and minimum measure for, bank capital. The Basel Committee designed the 1988 Accord as a simple standard so that it could be applied to banks in several jurisdictions. It requires banks to divide their exposures up into broad ‘classes’ reflecting similar types of borrowers. A minimum capital of 8% of risk-weighted assets (RWAs) was given. For example, 0% for cash, 20% for claims on multilateral development banks, 50% for residential mortgages and 100% for loans to the private sector. These risk-based capital charges roughly attempted to create a greater penalty for riskier assets (Jorion and Khoury, 1996).

While the 1988 Accord was initially applied only to internationally active banks in the G10 countries, it quickly became acknowledged as a benchmark measure of a bank's solvency and is believed to have been adopted in some form by more than 100 countries (KPMG, 2007).

The 1996 Amendment

The 1988 Basel Accord was soon proved insufficient and rendered obsolete by rapid changes in the financial sector. The 1996 amendment covered the four major risk categories of market risk (Akkizidis and Khandelwal, 2007:82–83):

- Interest rate-related instruments;

- Equities;

- Foreign exchange risk; and

- Commodities.

Issues with the Basel I Accord

The world financial system has seen considerable changes since the introduction of the Basel I Accord. Financial markets have become more volatile, and a significant degree of financial innovation has taken place. There have also been incidents of economic turbulence leading to widespread financial crises – for example, in Asia in 1997 and in Eastern Europe in 1998. In addition, advances in risk management practices, technology and banking markets have made the 1988 Accord's simple approach to measuring capital less meaningful for many banking organisations. For example, the 1988 Accord sets capital requirements based on broad classes of exposures and does not distinguish between the relative degrees of creditworthiness among individual borrowers.

In a similar manner, improvements in internal processes, the adoption of more advanced risk measurement techniques, and the increasing use of sophisticated risk management practices, such as securitisation, have changed leading organisations' monitoring and management of exposures and activities – this has been the result of Basel I. However, supervisors and sophisticated banking organisations have found that the static rules set out in the 1988 Accord have not kept pace with advances in sound risk management practices. This suggests that the existing capital regulations did not reflect banks' actual business practices. In other words, it was not sufficiently risk sensitive (KPMG, 2007).

The Basel II Accord

In June 2004, the Basel Committee finalised a comprehensive revision to the Basel Accord. In the European Union, the new Capital Adequacy Directive began to apply to all banks from 2007 onwards, with the most advanced methods being viable from 2008. US regulators decided to apply Basel II to a small number of large banks, with other banks subject to a revised version of Basel I.

How does Basel II differ from the 1988 Basel Capital Accord? The Basel II Framework is more reflective of the underlying risks in banking and provides stronger incentives for improved risk management. It builds on the 1988 Accord's basic structure for setting capital requirements and improves the capital framework's sensitivity to the risks that banks actually face. This will be achieved in part by aligning capital requirements more closely to the risk of credit loss and by introducing a new capital charge for exposures to the risk of loss caused by operational failures (EIIB, 2010c).

The Basel Committee, however, broadly maintained the aggregate level of minimum capital requirements, while providing incentives to adopt the more advanced risk-sensitive approaches of the revised framework. Basel II combines these minimum capital requirements with supervisory review and market discipline to encourage improvements in risk management.

Basel II also covers a wide range of risks which were not previously included in the original Accord, such as operational risk, country risk, legal risk, concentration risk, liquidity risk and reputational risk. Basel II marks a shift from transaction-based supervision to risk-based supervision (KPMG, 2007).

The Three Pillars of Basel II

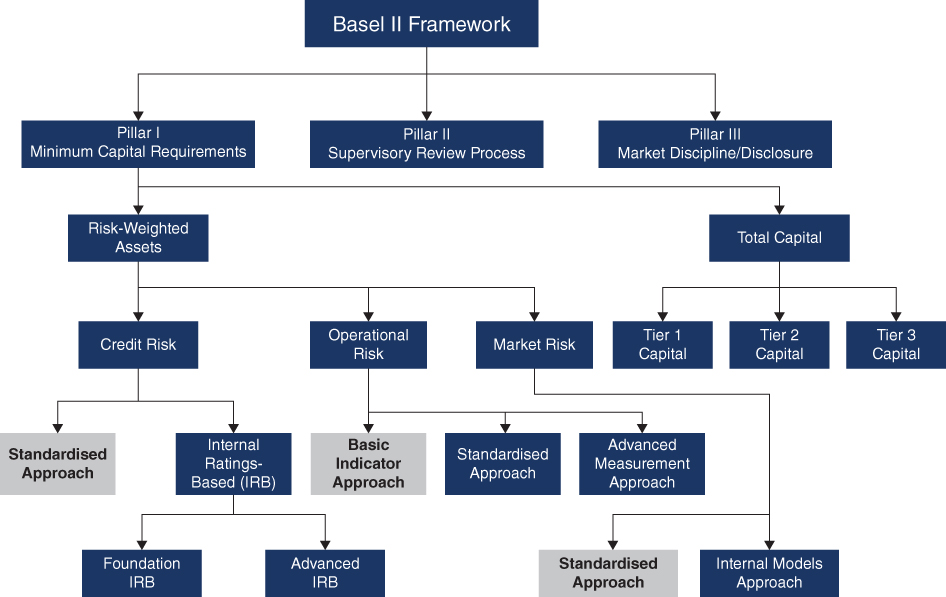

The overarching goal for the Basel II Framework is to promote the adequate capitalisation of banks and to encourage improvements in risk management, thereby strengthening the stability of the financial system. This goal was accomplished through the introduction of ‘three pillars’ that mutually reinforce each other and that create incentives for banks to enhance the quality of their control processes. The first pillar represents a significant strengthening of the minimum requirements set out in the 1988 Accord, while the second and third pillars represent innovative additions to capital supervision. Figure 4.1 provides an overall structure of the Basel II Framework and the sub-components of each of its main three pillars.

FIGURE 4.1 Structure of the Basel II Accord

Note: The shaded Approaches are the ones most commonly used by Islamic banks

When estimating the minimum capital requirements, there are two types of capital that can be calculated by financial institutions: economic capital and regulatory capital. As opposed to regulatory capital, which is set by regulators, economic capital is the amount of capital estimated by the bank's management to be maintained. Setting a higher limit for economic capital provides some room for leverage for banks. Economic capital is covered by Pillar 2, while regulatory capital is covered by Pillar 1 of the Basel II Accord.

Pillar 1 of the new capital framework revises the 1988 Accord's guidelines by aligning the minimum capital requirements more closely to each bank's actual risk of economic loss.

Basel II improves the capital framework's sensitivity to the risk of credit losses generally by requiring higher levels of capital for those borrowers thought to present higher levels of credit risk, and vice versa. The calculation of the minimum capital is presented with the help of the Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR), which is defined by Equation 4.1:

The equation defines the CAR as the ratio of the bank's capital (Tier 1 and Tier 2) to its RWAs, and it should not be lower than 8%. However, the regulators in each jurisdiction are given the discretion to impose a higher percentage if required).

Three options are available to allow banks and supervisors to choose an approach that seems most appropriate for the level of sophistication of a bank's activities and internal controls.

Credit risk capital charge Credit risks are of such great importance to banks from the regulators' perspective that the original 1988 Capital Accord required capital only against credit risks for on and off balance sheet assets. The primary concern of regulators is that banks should be aware of their credit risk and maintain a minimum level of capital to overcome any instability caused by default by a client. Basel II classifies assets into five risk categories (0%, 10%, 20%, 50% and 100%), depending on their rating.

Under the Standardised Approach (SA) to credit risk, banks that engage in less complex forms of lending and credit underwriting and that have simpler control structures may use external measures of credit risk to assess the credit quality of their borrowers for regulatory capital purposes.

Banks that engage in more sophisticated risk-taking and that have developed advanced risk measurement systems may, with the approval of their supervisors, select from one of two Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approaches to credit risk. Under an IRB approach, banks rely partly on their own measures of a borrower's credit risk to determine their capital requirements, subject to strict data, validation and operational requirements (BCBS, 2006).

Market risk capital charge The BCBS described detailed methods for the calculation of capital charges for (i) foreign exchange risk, (ii) interest rate risk, (iii) equity position risk, (iv) commodities risk, and (v) derivative trading. The capital charge for foreign exchange risk may exclude structured foreign exchange positions. The capital charge for interest rate risk is applied to the current trading book items. The Committee has prescribed two alternative models to measure market risk: the SA and the Internal Model Approach (IMA).

Operational risk capital charge Unlike Basel I, which focused on credit risk, Basel II includes an explicit measure for operational risk. This new capital Accord requires all banks to hold adequate capital against potential operational losses. The new framework establishes an explicit capital charge for a bank's exposures to the risk of losses caused by failures in systems, processes or staff, or to losses that are caused by external events such as natural disasters. Similar to the range of options provided for assessing exposures to credit risk, banks will choose one of three approaches for measuring their exposure to operational risk that they and their supervisors agree reflects the quality and sophistication of their internal controls over this particular risk area. Banks have the option to choose from the Basic Indicator Approach (BIA), the SA or the Advanced Measurement Approach (AMA).

By aligning capital charges more closely to a bank's own measures of its exposures to credit, market and operational risks, the Basel II Framework encourages banks to refine those measures. It also provides explicit incentives in the form of lower capital requirements for banks to adopt more comprehensive and accurate measures of risk, as well as more effective processes for controlling their exposures to risk.

While understanding the risks and the allocation of capital under Pillar 1 is a critical step, the core elements of supervision (Pillar 2) and market discipline (Pillar 3) are equally important. The Basel Committee believes that a well-designed capital requirement standard cannot be made effective in the absence of strong and prudent supervision.

Pillar 2 of the new capital framework recognises the necessity of exercising an effective supervisory review of banks' internal assessments of their overall risks to ensure that bank management is exercising sound judgement and has set aside adequate capital for these risks.

Supervisors will evaluate the activities and risk profiles of individual banks to determine whether those organisations should hold higher levels of capital than the minimum requirements in Pillar 1 would specify, and to see whether there is any need for remedial actions.

The Committee expects that, when supervisors engage banks in a dialogue about their internal processes for measuring and managing their risks, they will help to create implicit incentives for organisations to develop sound control structures and to improve those processes.

The Committee cautions that increased capital should not be taken as the only option for addressing risks. It advised the use of other means such as: strengthening risk management, applying internal limits, strengthening the level of provisions and reserves, and improving internal controls. Capital should not be treated as a substitute for adequate control or risk management processes.

Pillar 3 leverages the ability of market discipline to motivate prudent management by enhancing the degree of transparency in banks' public reporting. It sets out the public disclosures that banks must make that lend greater insight into the adequacy of their capitalisation. The disclosure requirements are based on the concept of materiality, i.e. banks must include all information where omission or misstatement could change or influence the decisions of information users. The only exception is proprietary or confidential information, the sharing of which could undermine a bank's competitive position.

The Committee believes that, when marketplace participants have a sufficient understanding of a bank's activities and the controls it has in place to manage its exposures, they are better able to distinguish between banking organisations so that they can reward those that manage their risks prudently and penalise those that do not.

Criticism of and Amendments to the Basel II Accord

As previously mentioned, after the Asian and the Eastern European financial crises in the 1990s, there was increasing concern that the Basel I Accord did not provide an effective means to ensure that capital requirements matched a bank's true risk profile. The risk measurement and control aspects of the Basel I Accord needed to be improved, which led to the introduction of the Basel II Accord. Similar concerns are being raised about Basel II after the financial tsunami that engulfed the world from 2008. As a result, voices have been raised criticising Basel II and requesting a new Accord for measuring and controlling capital requirements (British Bankers' Association, 2009).

“Shortcomings in the Basel II Accord will be definitely addressed” stated Engel (2010). This is essential, as the crisis has revealed that, on its own, without a strong liquidity pillar, Basel II is impotent. The Basel regime, which was always meant to be an evolutionary process, will change. The trend – apparent already before the crisis – toward loosening the definition of regulatory capital will be reversed. Definitions of capital will tighten and regulatory capital requirements will increase. Capital must no longer be looked at in isolation. The regulations must recognise the interplay between liquidity and capital and the ability of liquidity problems to become capital problems. In addition to developing a more prescriptive regime for liquidity risk, future capital rules should make excessive leveraging incrementally more expensive and address procyclicality, potentially by requiring banks to maintain larger capital buffers over the cycle (British Bankers' Association, 2009). It is worth mentioning that even before the crisis Basel II was widely criticised for encouraging pro-cyclicality, which dynamic provisioning is designed to offset.

The Basel Committee met in March 2009 to discuss embracing provisioning and higher capital. A statement on the BIS website stated that “This will be achieved by a combination of measures such as introducing standards to promote the build-up of capital buffers that can be drawn down in periods of stress, strengthening the quality of bank capital, improving the risk coverage of the capital framework, and introducing a non-risk supplementary measure.” On 13 July 2009, the BCBS announced that proposals for enhancing the Basel II Framework have been finalised. The Committee is strengthening the treatment for certain securitisations in Pillar 1 (minimum capital requirements). It is introducing higher risk weights for resecuritisation exposures to better reflect the risk inherent in these products and is also requiring that banks conduct more rigorous credit analyses of externally rated securitisation exposures.

The supplemental Pillar 2 guidance addresses several notable weaknesses that were revealed in banks' risk management processes during the financial turmoil. The areas addressed include:

- Firm-wide governance and risk management;

- Capturing the risk of off balance sheet exposures and securitisation activities;

- Managing risk concentrations;

- Providing incentives for banks to better manage risk and returns over the long term; and

- Sound stress-testing and compensation practices.

The Pillar 3 (market discipline) requirements have been strengthened in several key areas, including:

- Securitisation exposures in the trading book;

- Sponsorship of off balance sheet vehicles;

- Resecuritisation exposures; and

- Pipeline and warehousing risks with regard to securitisation exposures.

On 17 December 2009 the BCBS issued two consultative documents, one entitled ‘Strengthening the Resilience of the Banking Sector’ and the other ‘International Framework for Liquidity Risk Measurement, Standards and Monitoring’. These documents contain proposals to strengthen global capital and liquidity regulations with the goal of promoting a more resilient banking sector (BCBS, 2009b). Together with the measures already approved in July 2009, they form the core of the new Basel III Accord. In fact, Basel II is correct in principle but was wrong in implementation. Regulators should focus more on the implementation side.

BASEL II AND ISLAMIC BANKS

Islamic finance has become part of the global financial industry since the early 1990s; it is therefore subject to international standards and regulations. Capital adequacy will hence remain as a core issue for risk management, whether for conventional banks or Islamic banks, as the concept of having sufficient capital cannot be refuted in Islamic finance. Although the risks in Islamic banks are more contract-centric than the conventional product-centric, Basel II standards can still be applied with some adjustments. Thus, application of Basel II is a matter of adoption of the standards to the needs of Islamic banks.

Pillar 1

Unlike depositors of conventional banks, the contractual agreement between Islamic banks and investment account holders (IAHs) is based on the concept of profit and loss sharing (PLS), which makes IAHs a unique class of quasi-liability holders: they are neither depositors nor equity holders. Although they are not part of the bank's capital, they are expected to absorb all losses on the investments made through their funds, unless there is evidence of negligence or misconduct on the part of the bank. This has serious implications for the determination of adequate capital for Islamic banks as highlighted by Grais and Kulathunga (2007:79) in the following points:

- PSIAs should not be subject to any capital requirements other than to cover liability for negligence and misconduct by the bank, and to winding-down expenses.

- Investments funded by current accounts carry commercial banking risks and should be subject to adequate risk weights and capital allocation.

- Restricted PSIAs on the liabilities side form a collection of heterogeneous investments funds resembling a fund of funds. Therefore, banks holding such funds should be subject to the same capital requirements as are applicable to fund managers.

- The presence of displaced commercial risk and the practice of income smoothing have indirect implications for Islamic banks' capital adequacy, which a regulator may take into account when determining the CAR.

- Islamic banks acting as intermediaries may face a moral hazard issue. Since, as agent, the bank is not liable for losses but shares the profits with the IAHs, it may have an incentive to maximise the investments funded by the account holder and to attract more accounts than it has the capacity to handle. This can lead to investment decisions that are riskier than the IAH is willing to accept. Such ‘incentive misalignment’ may lead to higher displaced commercial risk, which necessitates higher capital requirements.

Grais and Kulathunga (2007) add that capital as it is classified in conventional banking cannot be used in Islamic banking. To be considered adequately capitalised, banks are required to hold a minimum capital (Tier 1 and Tier 2) equal to 8% of RWAs (in most cases). Tier 1 capital is the same for Islamic and conventional banks. However, in Islamic banks the reserves include the shareholders' portion of the Profit Equalisation Reserves (PERs), which is included in disclosed reserves. In Tier 2 capital, there are no hybrid capital instruments or subordinated debts, as these would bear interest and contravene Shari'ah principles. Furthermore, an issue is the treatment of unrestricted PSIAs, which may be viewed as equity investments on a limited term.

In addition, operational risk exposures appear to be higher in Islamic banks. Akkizidis and Khandelwal (2007) argue that the BIA as indicated by Basel II does not appear to be a case of perfect fit for Islamic banks. The 15% provision for operational risk of the average of three years' gross income needs to be examined thoroughly. The use of gross income as the BIA could be misleading in Islamic banks, insofar as the large volume of transactions in commodities and the use of structured finance raise operational exposures that are not captured by gross income. In contrast, the SA, which allows for different business lines, would be more suited, but it would have to be adapted to the needs of Islamic banks as the different risk weights proposed by the SA are not entirely applicable to their needs. In particular, agency services under mudarabah and commodity inventory management need to be considered explicitly. The allocation of 18% risk weight for business lines such as corporate finance, trading and sales, and settlements may not represent the true picture of risk exposures of Islamic banks as trading and sales in Islamic finance may include some murabahah transactions and some exposure from financing large accounts through istisna'a. Also, the SA allocates 12% to retail banking, asset management and retail brokerage, which does not fully apply to Islamic banks. As previously discussed, the risk exposures differ greatly during different stages of the Islamic finance contract and a blanket of 12% does not appear to map the risk exposure completely.

Furthermore, the IRB under credit risk, the IMA under market risk, and the AMA under operational risk are largely not applicable to Islamic banks for several reasons: first, the absence of widespread rating for Islamic finance; second, the changing nature of the relationships during the lifetime of the contract; and third, difficulties in estimating PDs (probability of default), LGDs (loss given default), and EADs (exposure at default) for Islamic finance.

Determination of Risk Weights

Assigning risk weights to different asset classes depends on the contractual relationship between the bank and the borrower. For conventional banks, the majority of assets are debt-based, whereas for IFIs, the assets range from trade financing to equity partnership; this fact changes the nature of risks. In some instruments there are additional risks which are not present in conventional instruments. Therefore, the calculation of risk weights for the assets of IFIs differs from the conventional banks because, according to Iqbal and Mirakhor (2007:126):

- Assets based on trade are not truly financial assets and carry risk other than credit and market risks;

- There are non-financial assets such as real estate, commodities, istisna'a and ijara contracts that have special risk characteristics;

- IFIs carry partnership and PLS assets, which have a higher risk profile; and

- IFIs do not have well-defined risk mitigation and hedging instruments, which raises the overall risk level of assets.

Another complication in risk weightings is explained by Alsayed (2008): as finance provided by Islamic banks is asset-backed, it is connected to the value of tangible assets. These assets are subject to volatility in their values (as distinct from depreciation). Banks are therefore exposed to not only the risk of default by a customer, but also volatility in the amount of credit mitigation available from the asset in the event of the need to realise their value. This means that there are not just RWAs for the book value of the outstanding credit facility, but also so-called ‘market risk charges’ in respect of the value of the assets collateralising the finance facility, at the start of the life of a facility, sometimes during the life of a facility, and at termination of the facility if the customer returns the assets to the bank and does not take title. The regulatory risk-weighting framework for Islamic banks is therefore more complex than that of conventional banks, and Islamic banks need additional risk management policies and procedures to manage these risks.

Pillar 2

The role of supervisors is more critical due to the evolving nature of the Islamic financial industry. Strong regulatory support in the form of monitoring and assistance is needed for Islamic banks. Some of the recommendations of Pillar 2 can be applied to Islamic banks, such as strengthening risk management systems, applying internal limits, strengthening the level of provisions and reserves, improving internal controls, focusing on concentration risk and business cycle risks, etc. A few of the Pillar 2 recommendations, although very relevant for conventional banks, do not hold ground for Islamic banks (Grais and Kulathunga, 2007). For example, liquidity risk, which is classified as residual risk under Pillar 2, is one of the most important risks in Islamic banks. Liquidity risk management is at the core of risk management in Islamic banking.

Ironically, after the recent financial crisis and the failure of some banks due to liquidity issues, the BCBS declared the need for a special directive to address liquidity. Regulators around the world began to introduce stricter liquidity standards and independent measures to monitor liquidity.

Pillar 3

The absence of comparable information is one of the main issues in Islamic financial reporting. Since Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions (AAOIFI) standards are not mandatory, there have been limited implementations, and the problem of non-comparability remains. Basel II recommendations regarding consistent and comparable information are highly applicable to the Islamic financial industry. Due to the social commitment attached to Islamic finance, there is special need for market disclosure, and therefore transparency is considered to be at the core of Islamic financial contracts, and thus should also be reflected in reporting.

The role of information in risk management in Islamic banking is more critical compared to in conventional banking, as PLS contracts are heavily biased toward availability of information for managing the risks. It is therefore mandatory to report the investment of funds, lines of business, activities and sources of revenue. Due to its nature and ethical foundations, social responsibility is of the utmost importance in Islamic finance. Moreover, direct market discipline is embedded in the risk-sharing principle of Islamic finance because IAHs share in the risk of the IFI and are not offered guarantees; incentives are created for a wider range of stakeholders in the bank to monitor its activities and risk-taking, which reduces the moral hazard problem. Along with this, there is greater emphasis on transparency, and thus Pillar 3 of Basel II has more relevance for the Islamic financial industry (Grais and Kulathunga, 2007).

Several recent studies by the World Bank and the IMF such as Greuning and Iqbal (2008), Hasan and Dridi (2010) and others have highlighted the significance of the appropriate balance of prudential supervision and market discipline in Islamic finance; and the related implications for the industry specifically and wider financial stability in general are also discussed.

BASEL III

The new tougher framework for international banking came into being in September 2010, when the new guidelines for risk management were announced by the BIS. This new set of rules was denominated as Basel III requirements and was accepted two months later in November 2010 during the G20 meeting in Seoul, South Korea. G20 leaders endorsed the Basel III capital and liquidity framework, and committed to fully adopt and implement these standards within the agreed timeframe that is consistent with economic recovery and financial stability – a finely judged balance. The new framework will be translated into national laws and regulations, and will be implemented commencing on 1 January 2013 and fully phased in by 1 January 2019.

As a result of Basel III, the capital ratio requirement has increased; the eligibility of capital has been tightened, thus reducing the amount of capital banks have to meet the required ratio; and the calculation of RWAs has changed leading to an increase for many institutions. Although implementing Basel III has its challenges and may ultimately not be sufficient to help banks globally withstand another financial blow, it is hoped that the new Accord will improve banking confidence and increase competition between banks. To achieve these objectives, the BCBS Basel III proposals are broken down into three main areas, as shown in Figure 4.2, that address:

FIGURE 4.2 Main components of the Basel III Accord

Source: Authors' analysis based on Basel III Framework from BIS

- Capital reform (including quality and quantity of capital, complete risk coverage, leverage ratio and the introduction of capital conservation buffers and a counter-cyclical capital buffer);

- Liquidity reform (short-term and long-term ratios); and

- Other elements relating to general improvements to the stability of the financial system.

The implications of Basel III for capital can be summarised as in Equation 4.2:

Equation 4.2 Implications of Basel III for capital

It should be noted that in general Basel III aims at reducing procyclicality and promoting counter-cyclical buffers through a combination of forward-looking provisioning and capital buffers. While considering Basel III directionally positive, Moody's (2011b) does not expect it to cure the structural challenges banks face from a credit perspective, including illiquidity and high leverage levels, as well as the tension between equity holders and bank managers whose focus is on maximising profits, in contrast to risk-averse bondholders.

IFSB PRINCIPLES ON CAPITAL ADEQUACY

Since Basel II did not answer all the risk management issues for IFIs, there has been a need for alternative and supportive standards, as “Basel II was drafted with conventional banking very much in mind”, as observed by Lowe (2010).

With the growing size of IFIs all over the world, there have been efforts to develop prudent supervisory norms. Thinking along the lines of Basel II and recognising the differences in the nature of Islamic banks, AAOIFI drafted a basic standard on capital adequacy of IFIs in 1999. This standard was further enhanced by the IFSB, which in December 2005 released the Guiding Principles of Risk Management for Institutions (Other than Insurance Institutions) Offering Only Islamic Financial Services (IFSB-1). Also in December 2005, the IFSB issued the first Capital Adequacy Standards for Institutions (Other than Insurance Institutions) Offering Only Islamic Financial Services (IFSB-2). This was complemented in March 2008 with the IFSB's Guidance Note in Connection with the Capital Adequacy Standard: Recognition of Ratings by External Credit Assessment Institutions (ECAIs) on Shari'ah-Compliant Financial Institutions (GN-1). Finally, in January 2009 the IFSB issued Capital Adequacy Requirements for Sukuk Securitisations and Real Estate Investment (IFSB-7), which deals with aspects relating to regulatory capital requirements for sukuk that are not covered in the previous issued standards.

Such intensive documentation is well prepared and addresses the relevant issues that are fundamental for the successful application of Basel II to IFIs. Archer and Karim (2007) highlight that, in spite of their high quality, these standards have been adopted in only a handful of countries. As with most standards, the respective banking regulators need to customise some of their own requirements.

The IFSB Standard on Capital Adequacy (IFSB-2) highlights that Islamic banks carry partnership and PLS assets that have a higher risk profile, and that Islamic banks do not have well-defined instruments for mitigating and hedging risks. In the case of partnership-based contracts such as mudarabah and musharakah, the bank is exposed to both credit and market risk that need to be analysed in a similar manner to the methodology of the Basel Accords. When such partnership-based assets are acquired in the form of tangible assets, such as commodities, and are held for trading, the only exposure is to market risk because credit risk is minimised by direct ownership of the assets. However, there is significant risk of capital impairment when direct investment takes place in such contracts and the investments will be held until maturity. Treatment of this risk within the Basel Framework is not straightforward and therefore requires special attention.

The key principle underlying the IFSB's approach is that PERs (and PSIAs overall) have a loss-absorbing feature, the intensity of which would not merit inclusion in eligible capital (the numerator of Basel II's capital adequacy ratio), but rather would allow for some deductions from computed RWAs (the denominator of Basel II's capital adequacy ratio), depending on the conservativeness of the regulator in terms of the degree to which PSIAs and PERs would be deemed capital-like instruments. PERs being a future claim of PSIA holders on the bank, they are not part of capital in accounting terms, and thus are not subject to distribution to shareholders. From a regulatory perspective, however, the treatment suggested by the IFSB is very subtle, particularly in Western jurisdictions.

The IFSB-2 Standard covers minimum capital adequacy requirements based predominantly on the SA for credit risk with respect to Pillar 1 of Basel II, and the various applicable measurement methods for market risk set out in the 1996 Market Risk Amendment. The IFSB is aware of the fact that some Islamic banks are progressively improving their risk management practices to the extent that they will be in a position to meet the requirement for applying the Internal Models Approach for measuring their risk exposures.

The IFSB (2005b) states that: “While this Standard stops short of explaining approaches other than the Standardised approach, supervisory authorities are welcome to use other approaches for regulatory capital purposes if they have the ability to address the infrastructure issues adequately. The IFSB will monitor these developments and plans to consult the industry in the future and eventually to make any necessary revisions.”

In respect of capital charge for operational risk, the IFSB Standard recommends using either the BIA or the SA given the structure of business lines of Islamic banks at the present stage. The Standard also recommends excluding the share of PSIA holders from gross income in determining capital charge for operational risk. This adjustment is necessary because Islamic banks share these profits with their depositors/investors.

Moreover, the Standard does not address the requirements covered by Pillar 2 (Supervisory Review Process) and Pillar 3 (Market Discipline) of Basel II, as the IFSB intends to cover these two issues in separate standards.

This Standard comprehensively discusses the nature of risks and the appropriate risk weights to be used for different assets. It deals with the minimum capital adequacy requirement for both credit and market risks of seven Shari'ah-compliant instruments: (i) murabahah, (ii) salam, (iii) istisna'a, (iv) ijarah, (v) musharakah and diminishing musharakah, (vi) mudarabah and (vii) sukuk. Discussion of each contract includes risk weights to be assigned to each for market and credit risks.

In calculating the CAR, the regulatory capital as the numerator shall be calculated in relation to the total RWAs as the denominator. The total of RWAs is determined by multiplying the capital requirements for market risk and operational risk by 12.5 (which is the reciprocal of the minimum CAR of 8%) and adding the resulting figures to the sum of RWAs computed for credit risk. The minimum capital adequacy requirements for Islamic banks shall be a CAR of not lower than 8% of its total capital. In this, Tier 2 capital is limited to 100% of Tier 1 capital.

The Shari'ah rules and principles, whereby IAHs provide funds to the Islamic bank on the basis of profit-sharing and loss-bearing mudarabah contracts instead of debt-based deposits, mean that the IAHs would share in the profits of a successful operation, but could lose all or part of their investments. The liability of the IAHs is limited to the capital provided, and the potential loss of the Islamic bank is restricted to the value or opportunity cost of its work.

In other words, the assets financed by IAHs are excluded from the calculation of the capital ratio, considering that IAHs directly share in the profits and losses of those assets, and the loss to the bank (as mudarib) is limited to the time and resources spent on the investments, except in the case of negligence or misconduct.

However, if negligence, mismanagement, fraud or breach of contract conditions can be proven, the Islamic bank will be financially liable for the capital of the IAHs. Therefore, IAHs normally bear the credit and market risks of the investment, while the Islamic bank bears the operational risk.

The IFSB Standard is defined in two formulae: standard and discretionary. In the standard formula, depicted by Figure 4.3, capital is divided by RWAs excluding the assets financed by IAHs, based on the rationale explained earlier. The size of the RWAs is determined for credit risk first then adjusted to accommodate for the market and operational risks. To determine the adjustment, the capital requirements for market risk and operational risk are multiplied by 12.5 (which is the reciprocal of the minimum CAR of 8%).

FIGURE 4.3 IFSB standard formula for calculating CAR

The second formula, depicted by Figure 4.4, is referred to as the supervisory discretion formula, and is modified to accommodate the existence of reserves maintained by Islamic banks to minimise displaced commercial, withdrawal and systematic risks. In jurisdictions where an Islamic bank has practised the type of income smoothing for IAHs, the supervisory authority has discretion to require the Islamic bank to include a specified percentage of assets financed by PSIA in the denominator of the CAR (represented by α in the Supervisory Discretion Formula). α is simply the percentage of depositors' risk absorbed by the Islamic bank as a percentage of capital required for assets funded by PSIAs. This would apply to RWAs financed by both unrestricted and restricted PSIAs. Further adjustment is made for PER and Investment Risk Reserves (IRRs) in such a manner that a certain fraction of the RWAs funded by the reserves is deducted from the denominator. The rationale given for this adjustment is to allow central banks and supervisors to decide on the profit-sharing/loss-bearing risk (displaced commercial risk) that IFIs are exposed to. For instance, the Bahrain Central Bank has ruled α to be 30% for the kingdom (Farook, 2008:19–20). This implies that PSIAs will bear up to 70% of their losses, while the remaining 30% will be borne by the shareholders of the bank.

FIGURE 4.4 IFSB supervisory discretion formula for calculating CAR

However, what if an individual IFI is more resistant to shocks in the local economy because it already undertakes pure performance-based PLS with PSIAs, i.e. the IFI has a lower displaced commercial risk? Farook (2008:19) argues that the supervisory discretion formula is applied on a jurisdictional basis, and assumes that all IFIs in that particular jurisdiction fit into the ‘one-size-fits-all’ category. He adds that most central banks that have applied this regulation did so in such a manner, and there is nothing particularly wrong with this in the absence of a better indicator of individual displaced commercial risk exposure. For example, the Central Bank of Kuwait approved the implementation of the amended capital adequacy ratio on local Islamic banks starting from 30 June 2009, aiming to give Islamic banks incentives to improve their ways of managing risks.

Table 4.2 summarises the main differences in Capital Adequacy Standards between Basel II and IFSB

TABLE 4.2 Capital Adequacy Standards: Basel II versus IFSB

Source: Combined analysis based on IFSB (2008b) and BCBS (2006). Reproduced with permission from Islamic Financial Services Board.

| Capital Adequacy Standards for Credit Risk | ||

| Criteria | Basel II | IFSB |

| Risk weight | Calibrated on the basis of external ratings by the Basel Committee | Calibrated on the basis of external ratings by the Basel Committee; varies according to contract stage and financing mode |

| Treatment of equity in the banking book | >= 150% for venture capital and private equity investments | Simple risk weight method (risk weight 300 or 400%) or supervisory slotting method (risk weight 90–270%) |

| Credit risk mitigation techniques | Includes financial collateral, credit derivatives, guarantees, netting (on and off balance sheet) | Includes profit-sharing investment accounts (PSIAs), or cash on deposits with Islamic banks, guarantees, financial collateral and pledged assets |

| Capital Adequacy Standards for Market Risk | ||

| Criteria | Basel II | IFSB |

| Category | Equity, foreign exchange, interest rate risk in the trading book, commodities | Equity, foreign exchange, interest rate risk in the trading book, commodities, inventories |

| Measurement | 1996 market risk amendments (standardised and internal models) | 1996 market risk amendments (standardised measurement method) |

| Capital Adequacy Standards for Operational Risk | ||

| Criteria | Basel II | IFSB |

| Gross income | Annual average gross income (previous three years) | Annual average gross income (previous three years), excluding PSIA holders' share of income |

The following example, depicted by Figure 4.5, demonstrates the difference in calculating CAR between Basel II and IFSB. Let us assume that bank A is an Islamic bank with the following balance sheet structure and that its regulator requires supervisory authority discretion (α) of 25%. The example proves that the risk-sharing characteristic of PSIAs requires special capital treatment. Calculating the bank's capital adequacy requirements according to the IFSB Standard formula lead to a higher CAR than for Basel II, meaning that Islamic banks that invest in partnership and PLS assets will have a better CAR due to the loss-absorbing feature of these asset classes. Figure 4.5 also demonstrates that calculating an Islamic bank's CAR according to the IFSB supervisory discretion formula is more practical, as the supervisory discretion formula is modified to accommodate the existence of reserves maintained by IFIs to minimise displaced commercial and withdrawal. When an Islamic bank has practised income smoothing for IAHs, the supervisory authority has discretion to require the Islamic bank to include a specified percentage of assets financed by PSIAs in the denominator of the CAR (represented by α). The IFSB supervisory discretion formula therefore gives a natural incentive to IFIs to engage in providing true economic returns to PSIAs and to stop the smoothing practice.

| Assets | Liabilities & Equity | ||

| £ mn | £ mn | ||

| Commodity murabahah | £150 | Demand deposits | £150 |

| Mudarahah investments | £100 | Unrestricted PSIAs | £400 |

| Musharakah investments | £120 | Restricted PSIAs | £350 |

| Trade financing | £400 | PER | £40 |

| Salam & Istisna'a | £100 | IRR | £50 |

| Ijarah | £150 | Shareholders' Capital | £30 |

| Total assets | £1,020 | Total liab. & equity | £1,020 |

| Total RWAs | £250 | ||

| RWAs financed by PSIAs | £150 | ||

| RWAs financed by PER and IRR | £15 | ||

| Supervisory authority discretion (α) | 25% | ||

| Market risk | £4 | ||

| Operational risk | £2 | ||

| Market and operational risk capital charge | £75 | ||

| (4 × 12.5 + 2 × 12.5) |

FIGURE 4.5 Computation of CAR for an Islamic bank

Equation 4.3 CAR according to Basel II Accord Pillar 1

Equation 4.4 CAR according to IFSB Standard Formula

Equation 4.5 CAR according to IFSB Supervisory Discretion Formula

As Wan Yusuf (2011) states, the capital adequacy framework for Islamic banks in Malaysia was implemented on 1 January 2008 and was developed based on the Capital Adequacy Standard for Institutions (other than Insurance Institutions) Offering Only Islamic Financial Services issued by the IFSB in December 2005. The Malaysia Framework is applicable to all Islamic banks licensed under Section 3 (4) of the Islamic Banking Act 1983. The analysis conducted on 12 Islamic banks shows that all banks follow the Capital Adequacy Framework for Islamic banking in Malaysia. The exception was in 2006, when Bank Islam fell below the requirements due to net loss of RM 1.30 billion. It was attributed to non-performing loans that severely affected the bank. However, the figure was improved to exceed the minimum regulatory requirement after additional capital injection. The analysis showed that banks in the study were over-capitalised. The excess capital could be used to reallocate assets where they could shift to more risky assets such as loans rather than less risky assets such as government bonds. This in turn would increase banks' profitability and thus enhance their efficiency by optimal utilisation of available resources. The study also revealed that domestic Islamic banks in Malaysia hold lower Risk-Weighted Capital Ratio compared to foreign Islamic banks, which can be attributed to familiarity with the local financial environment. It means that foreign Islamic banks are over-capitalised especially in the early years of establishment. The assets that banks hold tend to be under a safer risk category and the bank moves toward riskier assets as it gains a foothold in the industry. Not much difference exists between fully fledged Islamic banks such as Bank Islam Malaysia Berhad and Bank Muamalat Malaysia Berhad, which were established before 2003, and Islamic banks originated from Islamic banking windows, which were established after 2003, with regard to Risk-Weighted Capital Ratio. This could be due to the parent banks' familiarity with the local financial environment and understanding of the Malaysian financial system. Experience and familiarity leads banks to have a wider portfolio of riskier assets in order to fully utilise capital and enhance efficiency.

CAPITAL ADEQUACY AS A TOOL FOR RISK MITIGATION

As discussed in the previous chapter, risk mitigation is a key challenge for Islamic banks. Mimicking conventional risk mitigation techniques is not the best way forward because of the constraints imposed on Islamic banking by Shari'ah principles and mainly because the Wall Street conventional banking model has proved to be unstable and unsustainable. Some Islamic hedging tools have been developed; others are still work in progress, opening the door for huge opportunities in financial engineering. However, the risk-sharing characteristic of PSIAs in Islamic banking could greatly enhance risk management and mitigation in IFIs provided that proper pricing, reserving and disclosure are maintained. A measure of the extent to which the risks to shareholders are reduced on account of risk-sharing with IAHs should be the basis of any capital relief or lower risk weights on assets funded by PSIAs. The IFSB supervisory discretion formula is therefore a step in the right direction, with α representing the extent of total risk assumed by the PSIAs, with the remainder absorbed by the shareholders on account of displaced commercial risk. To take the IFSB standards forward, disclosure for IFIs needs to become more comprehensive and transparent, with a focus on disclosure of risk profile, risk-return mix and internal governance. This requires coordination of supervisory disclosure rules and accounting standards. In addition, the regulators should monitor and recognise the actual extent of risk-sharing by IAHs in assessing capital adequacy, and thereby encourage more effective and transparent risk-sharing with IAHs. Adequate disclosure by the IFI of the risks borne by PSIAs and shareholders should be a supervisory requirement for giving a low value to the parameter in the supervisory discretion. Thus, inadequate disclosure would result in a high value being set for α in addition to higher risk weights for profit-sharing assets, and hence granting little or no capital relief to the Islamic bank. In addition, Islamic banks that treat PSIAs as a substitute for conventional deposits should be dealt with by the regulator by treating these IAHs in the same way as liabilities for the purpose of calculating capital adequacy ratio. On the other hand, banks that practically implement the risk-sharing technique will be keen on proper disclosure to enjoy higher capital relief. This would provide the greatest risk mitigation tool for Islamic banks.

CONCLUSION

It should be noted that risks in Islamic banking are more contract-centric than in conventional banking, where risks tend to be more product-centric. Islamic financial contracts are characterised by the changing relationship between the contracting parties during the lifetime of the contract. This has a direct bearing on the risk exposures and relevant capital charges. Soundness and safety for banks depend to a great extent on the capital they hold. Since there is a constant dilemma to find the optimal mix of capital for business and regulatory purposes, the Basel I Accord was the first-ever systematic attempt at a global level to provide a framework for capital adequacy. Due to the rapid changes in the financial world, the original Accord proved to be insufficient to cover increasing complexities in financial markets. Basel II (and potentially Basel III) revolutionised the concept of risk management with the detailed analysis of credit, market and operational risks. The three mutually enforcing Pillars of Basel II have improved the Framework's sensitivity to the risks that banks actually face.

This chapter examined the three Pillars of Basel II and their relevance to Islamic banks. It has become obvious that, although some of the principles of risk management as proposed in Basel II are applicable to the Islamic financial industry, the Accord was developed with the perspective of conventional banks and, hence, does not apply to Islamic banks without suitable modifications.

The IFSB has played a key role in the development of risk management and capital adequacy standards in the Islamic financial industry. The IFSB's efforts should be considered as the first attempt at consolidating the Islamic financial risk management principles under one umbrella. More effort and research is needed in this underresearched area. Moreover, the IFSB standards should be made mandatory for Islamic banks to allow for wider implementation, consistency and standardisation of risk management principles across the IFI. This requires collaboration between regulators, IFSB, AAOIFI, Islamic banks and industry experts.

It should be mentioned that Sam Walton was indeed right, as finding capital is not the biggest challenge. It is the management and control of capital in an optimum way that worries financial institutions and regulators around the world. International standards like those issued by BCBS, AAOIFI and the IFSB act as capital guides that provide industry practitioners with vision for the right direction. It is up to individual banks to make proper use of the compass or lose their way along the hard financial journey.