6

Business Model Advantage

Without a business model, you don’t have a business.

Eric Hutchinson, COO and Co-Founder Madison Color

The world pharmaceutical industry is in trouble. Scientists say that the molecules from which new drugs are developed are offering fewer and fewer opportunities for new medicines. Also, the costs of getting drugs approved, by the FDA in the US for instance, is rocketing. This means the difficulty, time and costs for creating new drugs in the industry are rising inexorably, while older patents for leading drugs are expiring. The basis upon which Big Pharma competes is being eroded.

In response, organisations in the industry have been engaged in mega-mergers and acquisitions (M&A). For example, Johnson and Johnson’s $30bn deal with Swiss drug maker Actelion in 2017 to boost growth in its drug-making unit in anticipation of an impending decline in revenues from its top selling arthritis medicine, Remicade. Other giant M&As include Glaxo Wellcome’s $76bn merger with SmithKline Beecham to create GSK, and Bayer and Monsanto’s $66bn merger help them to better afford greater expenditure on R&D and meet the costs of regulatory compliance. These behemoths are reputed to be spending in excess of $5bn per year on R&D and yet their success in identifying new drugs is in decline. The underlying problems of limitations to chemistry, rising approvals costs and proprietary drugs coming off patent are not going away and pharmaceutical company strategic initiatives are not stemming the tide.

Put simply, big organisations in Big Pharma need new business models.

Business models have become very popular in recent years due to the staggering success of “Unicorn” companies such as Facebook, Uber and Airbnb. A unicorn (like the chimera discussed in Chapter 4) is a mythical animal that has been described since antiquity as a horse with a large pointed spiralling horn, and legend has it they are very rare and difficult to tame. It is a name that has been adopted by the US venture capital industry to denote a start-up company whose valuation exceeds $1 billion dollars. These organisations have new business models that have led to extremely rapid growth and promise very significant financial returns in the future, reflected in their market valuations of $350bn (Facebook), $30bn (Airbnb) $66bn (Uber).

Not surprisingly, this success has attracted a lot of attention from the media that has reified these organisations as “iconic” business models1 and they have become a source of inspiration for many would-be imitators.

Business models attract attention when innovation, in the way a business does things, brings about significant change to an industry or sector. Some might describe this as disruptive innovation. This can provide great advantages to the innovators and wrong-foot competitors who may be constrained from change in terms of resources, capabilities and mindsets.

An example of a well-known business model innovation, described by David Teece,2 is by Malcolm McLean, owner of a large US trucking company. He realised that when his trucks went to a port to load or unload, the loads from ships had to be broken down into various cargoes of different sized lots (“breaking bulk”), for loading onto lorries for transportation, and vice versa. This meant a lot of time was spent in the manual sorting of shipments, the loading and unloading of ships and warehousing. As an old pre-container joke put it, “dock workers used to earn $20 a day and all the Scotch you could carry home”.3 To McLean this seemed very inefficient and he was convinced that a lot of time would be saved if the cargoes came in a standard size. He therefore commissioned an engineer to design a road trailer body that could be removed from the lorry’s base and loaded onto ships. These “containers” could also be stacked one upon the other. He acquired a small steamship company and developed steel frames to hold the containers and soon pioneered the world’s first specialised cellular container ship, the Gateway City, launched in 1957.4 When McLean looked at the costs of his new container ship, he found that a one-ton load cost just 16 cents versus $5.83 for loose cargo.5 Standardisation of containers across the industry was necessary for McLean’s business model to work, so he made his patents free to the International Standards Organisation.6 The rapid spread of containerisation dramatically reduced shipping costs, shipping time, congestion in ports and losses through damage and theft. McLean’s new business model had changed the transport industry forever.

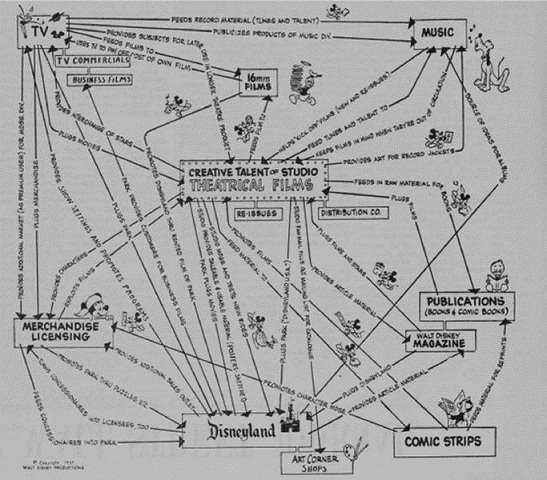

However, business models are far from new, having been in existence for as long as business has operated, even if not formally articulated. For instance, in medieval times goods were manufactured by members of craft guilds. The business model was one of producing high quality, high added value goods from a single workshop, using craft skills in small-scale production.7 In this sense, a change in business models in an industry is also far from new, with many documented examples of innovation in the 19th century, for example. And back before #businessmodel was a popular Twitter hashtag, innovative business leaders like Walt Disney (see Figure 6.1) and the McDonald brothers (see Live Case 6-5 at the end of this chapter) in the 1950s sought to capture and communicate how their business worked. And in the 1990s, Henry Mintzberg encouraged strategists to draw what their organisations actually did in order to win, in what he called “organigraphs” rather than thinking of hierarchical personnel charts as representative of an organisation (do an image search for “organigraphs” and you will find many examples).8

Figure 6.1 Walt Disney’s drawing of the Disney “business model” in 1957

However, interest in business models has achieved unicorn-like growth in the past decade. Recent organisational history abounds with stories such as McLean’s new business model disrupting the cargo industry; Amazon cutting out book retailers through direct distribution to customers to reduce the price of goods; Dell combining suppliers and its own distribution innovations to deliver compelling value to end customers; easyJet standardising on one aircraft type to allow operating efficiency and direct ticket sales to customers to undercut rivals’ prices; egg providing the first online internet bank service; and airbnb matching customer needs to suppliers of accommodation.

All of these business models have changed the way their industries operate and put severe pressure upon the “old” business models of incumbents. For instance, how should hotel companies with high fixed and variable costs and high prices per room react to an alternative supplier with minimal costs and far lower room prices? Not surprisingly, therefore, successful business models have also served as templates for other organisations to imitate, so Southwest Airlines’ innovative business model of a low-cost carrier has been successfully imitated by Ryanair and easyJet, Toyota’s widely admired “just-in-time” model is now used by most other car companies and McDonald’s franchising model is now widely used across multiple industries worldwide.

But what are business models? And what are they not? There does exist a lot of confusion about this. Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010), have argued that “[d]esigning a business model is closer to an art than a science”, a view that the pictures drawn by Disney, McDonald’s and Henry Mintzberg illustrate well. We outline some useful guidelines for strategists seeking to develop their skills in this art below.

What Are Business Models?

Business models are “stories that explain how enterprises work”.9 A good business model answers the questions “Who is the customer and what does the customer value?” and “What is the underlying economic logic that explains how we can deliver value to customers at an appropriate cost?” More formally stated, a business model can be defined as “the logic of the firm, the way it operates and how it creates value for its stakeholders”.10 It not only defines a business’s characteristics but also how they are combined in a recipe to make them work. A business model is therefore a statement of an organisation’s realised strategy11 and contains a logic of why it works. Some examples of common business models are as follows.

One-sided business models

Franchising

McDonald’s used franchising very successfully in order to expand rapidly around the world. Instead of building and operating its own stores to sell its burgers, McDonald’s, the “franchisor”, licensed other businesses, for an upfront fee, the right to use its brand name, processes and systems. This allowed McDonald’s to cut out a significant expense and so gain advantage over other competitors.

Cutting out the middleman

As the name suggests, this business model focuses on removing a segment of the value chain, such as wholesalers, distributors, agents. A famous example is Amazon targeting the book retail market, where a large part of the costs in the book value chain was in running bookshops. Amazon therefore cut out bookshops by selling direct to consumers via its website. This significantly reduced its operational costs in relation to bookshops and has given it a strong position in the book retail industry. They are now seeking to do the same for other product categories such as food retail.

Bricks and clicks

In this business model, a business is able to integrate its stores (bricks) with an online presence (clicks). For instance, bookshops, in response to the incursions of Amazon into the book retail market, now offer customers the opportunity to buy a book online and then pick it up at a local bookshop. The same applies to many other retailers.

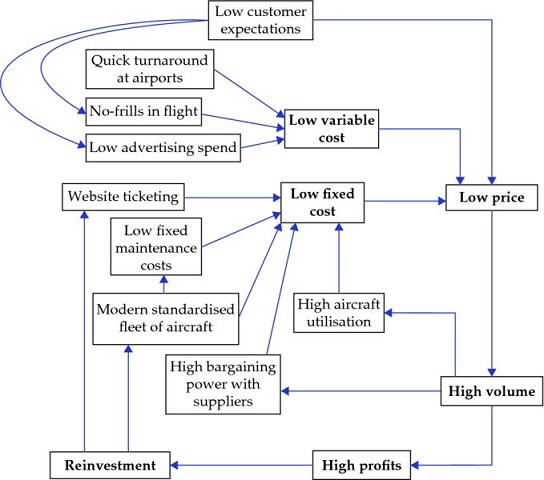

Low-cost model

Sometimes called a “no-frills” model, this is when an organisation identifies ways to reduce the features and/or services of a particular offering to customers. In terms of airlines, easyJet (see Figure 6.2) has been able to gain significant market share over incumbent competitors such as British Airways by offering a reliable safe service on short haul flights at lower prices by initially cutting out costs such as paper tickets, travel agents, in-flight catering and by using a single type of aircraft to reduce maintenance costs. Quicker turnaround times at airports also optimised asset utilisation.

Figure 6.2 easyJet’s business model

Some business models have virtuous cycles where feedback loops strengthen some components with each iteration. In terms of easyJet’s business model, low prices increase volume of sales that then improve easyJet’s bargaining power with aircraft suppliers. It also gives greater bargaining power with airports to the extent that some airports may even pay easyJet to provide a service to their destination.

Just-in-time

Made famous by the Toyota car company, the just-in-time business model was a radically new approach to the manufacturing process when it was introduced during the 1970s. The system focused upon cutting buffer stocks in each stage of the production process so that parts were only ordered when the process required them. The old system became known as “just-in case”. Just-in-time had huge advantages in reducing waste and also involved the workforce more directly in controlling inventory. An additional advantage was that it now allowed an assembly line to produce more than one model at a time. When American organisations introduced the techniques, commentators suggested they achieved as much as 70% reduction in inventory, 50% reduction in labour costs and 80% reduction in space requirements in the following five years.12

Razor-blade

Sometimes called a “bait and hook” model, this involves offering a basic product at a very low cost and then charging a premium for subsequent consumables. For instance, a razor maybe sold as “the bait”, at a price even below cost of production, certain in the knowledge that the consumer will then have to buy razor blades tailor-made to that razor, “the hook”, at a premium. Other examples of bait and hook include printers and ink cartridges, mobile phones and air-time.

Freemium

This business model offers a product or service for free and then charges a premium for special or advanced features. This is particularly attractive for internet products that can be downloaded in basic form. For instance, the software developer Adobe gives its document reader away for free but then charges a great deal for its document editor.

Sponsorship

This is where organisations will sponsor a high visibility activity in order that large viewing audiences will then see who has supported the event. For instance, Formula 1 is one of the most highly viewed activities in the world, with viewing figures in excess of 500 million per year. Organisations sponsoring F1 are doing so to increase their visibility to audiences worldwide and to monetise their brand through subsequent product and services sales.

Pyramid scheme

Often illegal, this business model works by promising payments or services to recruits for enrolling new members. The new recruits form the base of the pyramid and get returns as new members are added to the scheme. It is a business model as there is an internal logic, although ultimately it is not sustainable as liabilities quickly exceed assets.

Multi-sided/platform models

In multi-sided business models, the organisation creates value by enabling direct interactions between two or more distinct types of affiliated customers. In other words, the platform is only valuable to one customer if it is valuable to another. For instance, airbnb’s business model connects travellers looking for low-cost accommodation with people who have accommodation that they want to rent.

Network effect

The important point about network effects is that for every additional user of a product or service, the more valuable that product or service becomes. For instance, the more people who own mobile phones in a network, the greater the benefit to other users. Uber has used a network effect with great success as with every additional car available for hire, the greater is the demand for travellers and vice versa. This is an example of a two-sided market effect – as there are two sets of customers, travellers and drivers, and both benefit from each other’s value proposition.

Pay what you want/can

Due to an unfortunate change in grant status, owing to a currency crisis, one of our graduate students suddenly found himself unable to pay his student fees. The university was magnanimous in reducing the fees and allowing deferred payments but this still presented the student with a problem of how to pay. In desperation, he decided to cook meals in the evening for his friends based on the cuisine of his home country, Indonesia. Uncertain of price, he only asked them to pay what they thought it was worth. Soon word spread around campus of his cooking ability and the demand was such that by the end of his degree he had been able to cover his fees handsomely. His banana cake was legendary.

This sort of model is often associated with charities and a social purpose, or what are sometimes referred to as social business models, although they can often be used in a promotional way. They generally depend on trust, reciprocity, willingness and an ability to pay. An example that has benefited entire communities and their environment is ASRI in the Gunung Palung National Park, Indonesia. It aims to stop the poverty-poor health-deforestation cycle by working to empower local people to turn from loggers into forest guardians to protect an endangered rainforest. ASRI enables local people to access health care that they could normally not afford and, in return, villagers exchange items used in conservation work such as seedlings for reforestation or manure for organic farming, or participate in work like replanting parts of the park previously damaged by illegal logging. In this way, the villagers help ASRI to conserve their national park.

Collective business models

There can also be business models that involve large numbers of businesses in related fields. This may allow them to pool resources and share information. For instance, Airbus is a consortium endeavour between many leading European companies in order to build aircraft. A not-for-profit example might be a science park that creates an innovative community, benefits from collective facilities and may even have collective negotiating benefits with local authorities and other funding sources.

Other popular business models, that you may want to research further, include auction, loyalty, multi-level marketing, open-source, servitisation and subscription models.

How to Do It?

In order to develop a business model, you should remember that it has to fulfil the following functions:13

- Articulate the value created for users

- Identify a market segment and why users will pay for the product/service

- Define the value chain structure that will create and distribute the product/service and will support it

- Show how the organisation will be paid

- Estimate the cost structure and profit potential

- Describe the organisation’s position in the value network linking suppliers and customers

- Formulate the competitive strategy by which the innovating organisation will gain and hold advantage over rivals.

More succinctly, the business model logic can be articulated through four main dimensions of (1) customer identification, (2) customer engagement, (3) value chain linkages and (4) monetisation.14

Do it by drawing it

Business models can also be articulated and analysed through an activity systems perspective.15 This is best shown through visualisation. By drawing maps of the components of a business model and identifying key linkages, the processes supporting how a business wins in the marketplace can be detected (see Figures 6.1 and 6.2). Drawing the business model in this way also allows mangers to openly discuss and debate the importance of key components.

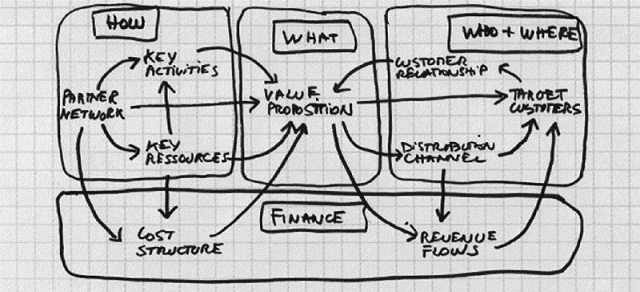

A popular template for designing a business model is provided by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010) in Business Model Generation. This book provides a basic structure, called a “business model canvas”, that businesses may populate (see Figure 6.3). It consists of nine building blocks that a business model needs to address:16

-

Customer segments

Which segments to serve and which to ignore? Design the model to fit their specific needs.

-

Value propositions

Which bundle of products and services solve a customer’s problems or satisfy a need?

-

Channels

How to communicate and reach customers through raising awareness, helping them decide, allowing them to purchase, delivering a value proposition and providing post-purchase support?

-

Customer relationships

What sort of relationship to have with customers, i.e. automated or personal? How should customers be retained or acquired?

-

Revenue streams

Are these transaction revenues and/or recurring revenues? Each may be affected by different pricing mechanisms.

-

Key resources

What are the most important assets needed to make the model work?

-

Key activities

What are the things that a business must do – the key capabilities – such as supply chain management, problem solving and service delivery?

-

Key partnerships

What partnerships or alliances exist or would be needed to optimise the business model, reduce risk or acquire resources? For instance, are there joint ventures, sourcing arrangements or strategic partnerships?

-

Cost structure

What are the costs incurred in delivering the business model?

Figure 6.3 Example of a business model template (Source: adapted from the Business Model Canvas, https://espriex.co/businessmodel-canvas)

Through completing the template, an organisation may understand how its existing business model is configured and also consider how a new model may be constructed.

Another visual approach to business model design which seeks to utilise proven strategic frameworks more directly is the book Strategy Builder by Cummings and Angwin (2015), and the associated StrategyBlocks Builder app. ‘Strategy Builder’ shows how an organisation may identify critical ingredients for a business model through strategic analyses and how underlying analytic models maybe connected together to provide various strategic options for the future.

Selecting the right business model is generally a process of trial and error as it is unlikely to arrive fully formed at the outset. Evidence needs to be assembled to validate conjectures and hunches about what the customer wants, what the costs will be, how competitors might react and the terms required by suppliers and distributers. This can be likened to running experiments and hypothesis testing where questions are formed for which evidence is gathered and tests run. It is important that the experiments are representative of the larger market and it is far better to try out a business model on real paying customers, for instance, than just asking your friends.

This causation approach tends to be one of testing the existing market. However, it may be useful to reveal new information and new possibilities. This approach is called effectuation and can be achieved by taking actions that might reveal or create new information. For instance, analysing a chef’s meals using causation would cause the observer to ask for something from the menu and then test the meal’s quality. Using effectuation, the observer would ask the chef to make something and see what happens. The former is working with a specific goal in mind, the latter is about possible goals. It may be important to move quickly in the business model development process, learning fast and making rapid adjustments. In this sense, creating a business model involves experimentation, trial and error, analysis and inspiration, and is therefore as much an art as a science.

Barriers to Business Model Innovation

A new business model may provide significant benefits over a prevailing model in terms of novelty, lock-in, complementarities and efficiency.17 There are many examples of new business models wrong-footing incumbent companies, such as Amazon’s entry into book retailing damaging the business of bookshops, airbnb’s business model threatening hotels and Uber challenging the licensed cab industry. In the face of such major threats it would seem self-evident that incumbents should adjust their business models.

However, incumbent managers, loyal to previous ways of operating, are likely to resist this sort of innovation because it is unfamiliar to their way of perceiving the organisation, the business’s “dominant logic”, and it may threaten their own positions. Also, a new business model may not be as profitable as the existing model, so proving hard to justify. A good example of this was Kodak developing a new technology for photography, the digital camera. This threatened the core business model of photo film production and sales, which was highly profitable at the time. Incumbent managers therefore resisted the new business model and did not commit fully to the new technology on the basis it would cannabalise existing products. Competitors did commit, however, and consumer tastes changed rapidly, causing Kodak to fail.

A business model defines the architecture of a business and it may expand from this foundation. But once established, businesses often experience immense difficulty in changing their model, as in the case of Kodak above. However, when there is a significant threat from the external business environment, such as the financial crisis of 2009, this might bring about business model adaptation. If the strategic orientation of the organisation is appropriate.18 So, for instance, a business that is defending its domain, such as Kodak, is far less likely or able to engage in business model adaptation than a business pursuing market development that has routines and processes allowing it to respond effectively to external stimuli.19

Business model adaptation though, through incremental changes, is unlikely to build sustainable competitive advantage. Refinements to business models may allow reduction in costs or some increased value to customers and higher returns overall and this can be sustained if the model cannot be easily copied. But in most cases imitation will occur, as the idea and logic behind the model is generally easy to understand and hard to protect by patent, for instance.

What may protect a business model are the distinctive resources and capabilities that underlie it. For example, a specific technical competence in R&D may be very hard to access, customers may be tied into a long-term relationship so “locking out” competitors, and some organisations have a distinctive history that cannot be copied. Competitors can also be handicapped by their own structural rigidities so that easyJet’s use of just one fleet of aircraft cannot be easily copied by flagship carriers, such as British Airways, that already have complex systems and resources supporting multiple types of aircraft for a broader range of destinations. For British Airways, to try to move to one aircraft type would immediately render many of its routes impossible to service and result in huge layoffs and restructuring.

A further barrier may be that there is a lack of transparency of the business model that prevents competitors from really understanding how it is implemented, or how it is that customers really appreciate the product or service.

An organisation may also be reluctant to copy a business model if it involves cannabalising existing sales and profits, as described earlier for Kodak. There may also be resistance if copying will involve upsetting important business relationships. Of course, new entrants to the industry will not be constrained by these issues and so competition is likely to increase.

As business models may be subject to innovation it is important, therefore, to consider not only how a business model may work but also to work out what could be “isolating mechanisms” to prevent or hinder imitation by competitors. If possible, patents may be effective in preventing copying as may the rate of releasing innovations to the market. For instance, Zara, the fast fashion company, is renowned for keeping its clothes on display for very short periods of time to prevent imitation. Other classic ways of preventing imitation are rapidly achieving economies of scale and establishing market dominance.

Is a Business Model the Same as a Strategy?

A business model defines how the organisation creates and delivers value to customers and then converts payments to profits.20 It is a reflection of the organisation’s realised strategy.21 At that moment strategy and business model coincide. However, this is insufficient to create sustained competitive advantage. The reason is that the main elements of the business model are often quite easy to detect and prone to imitation.

In practice, successful business models, such as McLean’s containerisation, often become shared by multiple competitors. Indeed, Southwest Airlines’ business model has been copied successfully by Ryanair and easyJet, among others, and there are now many imitators of airbnb’s model. However, when there is a need to adjust the business model, as the context changes, for instance, there is then a need for strategy – the business model itself will not give guidance to contingencies.

An example given by Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart is that an organisation’s business model may be functioning well until the wider economy goes into recession. The business model may no longer function effectively and it is the organisation’s strategy that should determine how it might be changed.22 A strategy will need to make choices about resources and capabilities, policies, governance structures, markets that are the raw materials of business models in order to design, redesign and undo them to reflect contingencies as they occur. For instance, when egg was created as the first internet bank, incumbent banks that had relied for decades on a branch network for competitive advantage now perceived these expensive assets as “structural rigidities”, or sources of cost that no longer gave them an advantage with the customer. Bank branches, previously central to their business model now impaired their ability to compete and a strategy that engaged with the customer electronically was needed to allow them to adjust – the old model was no longer adequate.

There can be many contingencies for which strategies are needed and for which business models give no guidance. For instance, macro-shocks may undermine the current business model, making it redundant, and may also create possibilities for new ones. As an example, one reason for the take-off of airbnb in 2008 was the economic downturn causing travellers to search for cheaper accommodation and for property owners to search for new ways to generate income.23 Similarly, the actions of industry players such as competitors, new entrants, suppliers, customers and complementors may also undermine business models and create new opportunities.

Game theory may give some insight into these changes as the actions, or potential actions, of a competitor or new entrant, for instance, may affect an organisation’s choice of one business model over another. It is worth noting that this sort of strategising is not visible to external audiences such as investors who only see the current business model. Strategy therefore is the creation of business models and choices about which business model to use. Ryanair was on the verge of bankruptcy in the early 1990s and needed a new strategy. They came up with four alternative plans, such as adding business class and exiting the industry, and out of those chose to become the “Southwest Airlines” of Europe with a no-frills service. This was their strategy and the way it was executed was the resulting business model – the new Ryanair.24

So, while it might be fair to say that without a business model, you may not have a profitable business (as the quotation with which this chapter began indicated), just having a business model is not enough to succeed strategically, to “win” or to achieve your strategic goals, other than in the short term. This is why it forms just one of 12 strategic pathways in this book.

We began the chapter by reflecting on the need for new business models in the pharmaceutical industry. The conventional business model does not enable Big Pharma organisations to adjust to new challenges in the macro, industrial and competitive environment.

They need to adjust and it is evident that several of them are trying to do things differently. Johnson & Johnson is offering a new drug for bone cancer, Velcade, to European Health Ministries with a novel proviso. If the drug is not efficacious in 90% of patients, the Ministries need not pay for it. While this approach might reduce the risks of testing drugs, it does little to address the problem of reducing the productivity of research. Other Big Pharma organisations are reducing their exposure to R&D and investing in marketing in order to secure the supply chain. They are then outsourcing R&D to bio-tech firms for them to take on the research risk and using venture capital techniques to capture value should the bio-tech firms succeed.

This may well be a new business model that foregrounds the importance of controlling marketing of drugs to customers and outsources R&D. It may represent a provisional solution to customer needs and may need to evolve to be fully effective. However, it will also mean an evolution in the dominant logic of those organisations, which may be difficult to achieve as organisational structures, personnel, resources and capabilities are aligned to the “old” business model. The ability of organisations to overcome inevitable internal barriers to change by coordinating all of the organisations’ resources, alter the way they do things and evolve, is the subject of the next chapters in Strategy Pathfinder: Corporate Advantage, New Ventures, Crossing Borders and Leading Strategic Change.

Business Model Advantage Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

6-1 IKEA: Kit-Set Business Model

Seventeen-year-old Ingvar Kamprad founded IKEA in his hometown of Agunnaryd in the south of Sweden in 1943. By 2016, Forbes magazine listed him as one of the ten richest people in the world and the owner of a more than US$ 40 billion fortune. It’s fair to say that IKEA’s business model has made Kamprad a very wealthy man.

IKEA is a compound acronym made up of Ingvar Kamprad’s initials (name of the founder), Elmtaryd (the farm where he grew up) and Agunnaryd. Now owning 340 stores in 28 countries, IKEA has sales of around €32bn and approximately 783 million store visits per year, indicate that perhaps no other retailer has had such success in consistently rolling out its business model around the world.

This business model has gradually changed the way consumers view furniture. Previously, furniture was considered an expensive investment intended to last at least a decade or a generation. But not for IKEA, who created well-designed products that, while robust and durable, were designed to be easily produced in kit-set form, intended for immediate use and also for disposal when they wore out or people moved on.

IKEA’s simple aesthetic clean lines and relatively low price-point appeal to younger consumers, such as new families setting up home, apartment dwellers, those just graduated from college and even those going to college. Although not the cheapest available, IKEA’s furniture supplies everyday needs and is affordable. It provides good value in terms of design and quality.

The stores are also attractive shopping destinations as they are elaborate and show furniture in different contexts – something that is hard to imagine or try out when you view individual products on a typical shop-floor or online. The vast layout of the shops allows a huge variety of products to be displayed, so there is great variety from which to choose. Customers generally must follow a wandering pathway designed to encourage them to weave past as much product as possible, something that helps stimulate multiple purchases and impulse buys.

Good cafeterias at the end of the “trail” act as a welcome reward and provide an opportunity for people to think through the order numbers of the products they have seen on display before moving on to the attached warehouse where a vast array of product is stored – in kit-set form.

While the stores encourage shoppers to wander and linger, IKEA’s operations are lean. There is limited customer service at stores with few staff about and customers are expected to walk throughout the store making their own selections and then collecting their items from the warehouse and transporting their items to the checkout. Because most of the items of furniture are flat-packed as small as possible (this is a key consideration factored into every IKEA design), the vast majority of products can be carried home in customers’ cars – meaning there is no need to employ a delivery service or time to change one’s mind on the way home.

The stores attract large volumes of customers even though they are located out of town on arterial highways. But the good news is that these wide-open spaces allow for large purpose-built parks for the cars that will be needed to take the products home.

There is no doubt that IKEA has a huge customer following and there are high levels of repeat buying – something that is further encouraged and enabled by an approach to furniture design which is modular and organised into product “families”, allowing coherence between many IKEA products. Labelling on the furniture is self-explanatory allowing easy self-assemblage and indicating how the product can be combined with others in the IKEA range. And every product comes with complementary catalogues (effectively furniture and living magazines) which help inspire further visits back to the store, and, of course, further purchases.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

- Some suggestions as to the key dimensions of the IKEA business model are provided below, but you may be able to identify others.

- Customer identification: young customers with low disposable income and growing levels of aspiration

- Customer engagement: mass marketing and large stores that provide products in situ and allow for social interaction

- Value chain linkages: efficient supply chain linkages and large stores with customer transport and self-assembly all allowing for scale economies and high efficiency

- Monetisation: low costs and design quality allow competitive medium pricing. This allows good margins to be reinvested in design and in IKEA’s expansion.

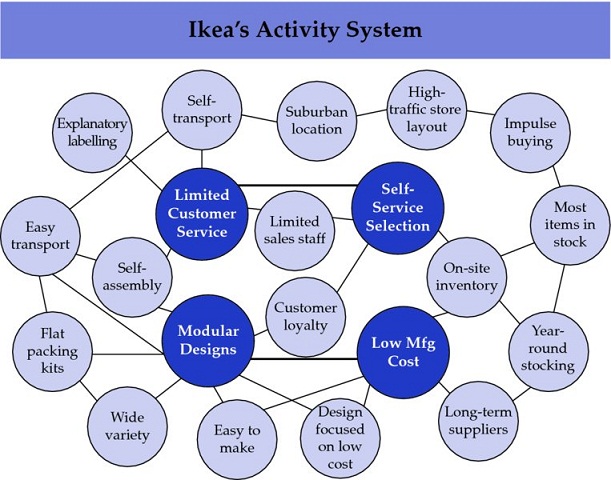

Draw the activity system of IKEA.

Figure 6.4 shows an attempt to draw IKEA’s business model as an activity system. See if you might be able to draw this kind of network in a more creative way.

- The main message to be learned when thinking about this third question is that most competitors could copy parts of IKEA’s activity system. Many could produce furniture more cheaply, others could produce more compelling designs, some could offer less service and others more.

However, it is the combination of all of these things – paired with a design ethos that appeals to a specific customer group at an affordable price and a brand identity that has been built up over many decades – that makes IKEA’s activity system and business model compelling, highly successful and difficult to replicate.

Figure 6.4 IKEA’s activity system

(Source: adapted from Carl Lupke, “Strategy, Business Model and Business Plan”, https://www.slideshare.net/Brainpowersolutions/strategy-business-model-and-business-plan)

![]()

6-2 Synear: Dumplings to Villas

Synear Quick-Frozen Food Company was founded in 1994 in China’s southern provinces by a group of young and ambitious Chinese mavericks, including journalism graduate Li Wei (who has recently become one of China’s first female billionaires). Synear began as a manufacturer of dumplings. China’s “dragon head”, or leading player, in the quick-frozen food industry, Sanquan, was located just one mile from Synear’s base. As a newcomer with little experience in the industry, Synear’s founders perceived this “dragon head” as a model and aimed to copy Sanquan’s factory layout, administrative systems, training processes, supplier relationships and recipes, as nearly as possible. They set out to become, in their words, a “mini-Sanquan”.

While this approach enabled Synear to get its operations off the ground, it created a number of problems. Perceiving Sanquan as “best practice” and duplicating its products made it hard for customers to differentiate the two companies’ offerings. Inevitably, this led to a price war that Synear, given its much smaller operating base, was in no position to win. Synear management found that the only way it could shift sales in this environment was to offer its dumplings on credit, but the difficulties associated with deferred payments by customers led to a serious cash-flow problem.

Synear responded in two ways. First, to improve cash flow, it integrated forward into restaurants that utilised Synear products but enabled bigger margins and improved cash receipts. Second, it began to think about how it could differentiate its dumplings from those of Sanquan. This it did in two ways that might be seen as contradictory by followers of classic Western strategic management theory.

On the one hand, Synear abandoned what it described as “high-income” customers and focused instead on those with middle or low incomes who would sacrifice some degree of quality for a lower price. This enabled it to focus on every step of the processes it had copied from Sanquan and examine how costs could be cut. For example, Synear decided not to sell its dumplings to wholesalers and stores in traditional small packets, but in bulk cartons from which shoppers could pick the amount they wanted and pay by weight at lower prices. Synear was soon able to market its wares as the lowest priced dumplings on the market, knowing that Sanquan, whose success was wedded to its broad appeal to all income groups and traditional dumpling manufacture techniques, would find it difficult to follow.

On the other hand, however, Synear sought to differentiate its dumplings in ways that appealed to younger people like themselves. Synear’s managers had watched with interest the emerging awareness of environmental issues among younger consumers. To match these interests, they decided to go after the newly developed Chinese “green product certificate”, which assured customers that a product was made of natural or organic ingredients and that the manufacturing process did not pollute the environment. Additionally, it introduced natural dyes to some products to create green dumplings in addition to the traditional white colour. This made Synear dumplings stand out in the marketplace and attracted attention to the green policy. A yellow colouring was also added in honour of the Yellow River, being of great cultural and spiritual significance in the region.

While its lack of experience in frozen foods had been seen as something of a hindrance when Synear started life, it was now beginning to use the fact that its people weren’t ingrained with traditional approaches and could therefore think about making and selling dumplings in new and different ways. Other innovative approaches that Synear developed included:

- Convincing Sanquan to develop an alliance that would give the companies added muscle to jointly procure produce at lower prices.

- Using some of its underutilised frozen food facilities to develop a range of ice cream.

- An alliance with a local sales agent willing to put money into the company. This agent became the company’s second largest shareholder. The cash injection enabled dumpling and ice cream production to double.

- Another alliance with a regional agent who had a strong hold over the market in three provinces in China’s southwest region, provinces where companies like Sanquan had yet to establish a presence. This provided a ready market for the increased production described above. While ensuring this agent’s cooperation required an agreement to sell to him at little more than cost, his networks enabled Synear to dominate the frozen dumpling market in these provinces within a matter of months.

- Broadening its portfolio by buying the recipes for proven products (a particular regional black sesame dumpling, for example) from smaller companies that lacked the finance to develop the market for such items.

- A commitment to developing very good and very professionalised relationships with banks and government agencies – relationships that, over time, would help with obtaining the capital and permits required for further developments. This was something that traditional and less entrepreneurial Chinese companies had generally not focused on.

The development of these new strategies meant that business was getting much better for Synear, but as time went by the partners became increasingly aware of the relatively low margins that the dumpling and restaurant businesses provided. It was time to diversify further. However, once again the direction the company took might be seen by some to make little sense when analysed using classical Western decision-making models.

Synear’s managers made the decision to enter the real estate business. However, this time they realised that they needed to differentiate themselves from the competition from the outset. There were literally tens of thousands of property development businesses in China and most of them were much the same as one other, but Synear sought to mark itself out as different by building on the ethos that had developed around the dumplings. Synear sought to focus on low-cost housing. This meant building some distance out from the city. But this then enabled a connection to another of Synear’s tenets to come into play. Synear would build on newly developed forestland and would emphasise the green, environmentally sound and tranquil aspects of their properties to young middle-income house buyers. Thus, Synear developed four principles around which it would focus its property development energies. They are as follows:

- In Chinese cities, most people live in apartments and most are sick of concrete and steel buildings. People want houses – homes with gardens, grass and flowers. All our buildings are villas.

- All our buildings are far away from city noise. At least 20 kilometers away from the city so that people can plunge themselves into a paradise after a hard day’s work.

- The backgrounds of our houses are very green and tranquil. Our homes are built in a forest in surroundings that are like rural areas.

- All our houses are near the “Mother” (or Yellow) River. People have a special emotion for the river and living near her gives them a feeling of harmony and relaxation.

The company that began as a frozen dumpling maker still makes dumplings. But it now makes much more, and each product in its diverse range (dumplings, restaurants, property) reinforces the brand image of the other. The company is now one of China’s largest food producers and was an official supplier to the Beijing Olympic Games. Associated with this, Jackie Chan has been recruited as the face of Synear’s new Gold Medal Series of quick freeze food products. And, according to Forbes magazine, Li Wei is now the 891st wealthiest person in the world.

6-3 Friendsurance: I Get By with a Little Help From …

The very first insurance companies were cooperatives, established in the middle of the 19th century. Business historian Dan Wadwhani notes that at this point in time, private and publicly listed companies found it difficult to conceptualise a model whereby money could be made by encouraging customers to place bets against themselves, or on their own lives, when they would only receive their winnings after they were dead. Cooperative insurance companies emerged to fill the void (earlier, in Europe, Trade Guilds – which had cooperative characteristics – also provided insurance-like services). Eventually, these organisations showed how a business model that saw value in providing for others, even though “the customer” would gain no material benefit or would only gain after some kind of failure, could work, and the global giants that dominate the insurance industry of today entered the market and gradually took it over.

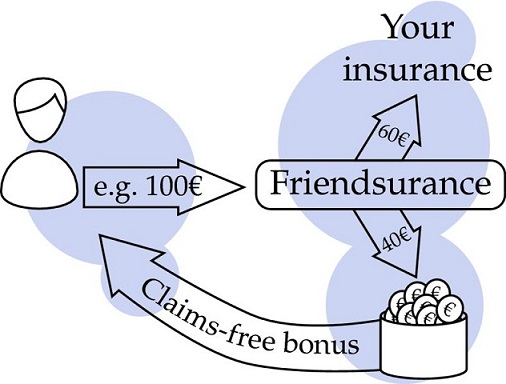

It could be argued that, since then, there has been very little innovation in the industry. But a German company called Friendsurance (www.friendsurance.com) is now promoting a business model that is at once innovative and very old-fashioned.

Friendsurance acts as a peer-to-peer broker for people who want to group together with friends, neighbours, family, colleagues or any combination of these, bundles these up into a unit, and then seeks insurance for the group from one of its insurance company partners. The group is then insured as if it were an individual so no-claims bonuses are returned to the whole group. This is a key feature as it greatly reduces the likelihood of fraud or false claims since such practices would disadvantage one’s friends and family (rather than “the big faceless company” that customers often think of when they think of insurance). If nobody in a group claims, the money returned to customers can be as much as 40% of their premium. This acts as a real incentive for people in a group to provide extra support and care for their fellow insurees, which further diminishes the chances for misfortune.

By gathering “friends” under one umbrella, and reducing the collective number of claims, the model also reduces processing costs. And these reduced risks and reduced costs help Friendsurance broker good rates and no-claims rebates from insurance companies.

Friendsurance claims that the simplicity of the approach of using them as a broker also makes it easier for customers to see and understand the benefits of their business model, than to comprehend the often convoluted and opaque practices of traditional insurance companies. To illustrate, they explain their strategy on their website with the simple graphic above.

Friendsurance is growing fast, proving especially popular with young people in Germany (the most valuable segment of the market for insurers) and has already been touted in the business press as having developed one of the most innovative new business models of the past few years. It is changing the way that many think about insurance. As Shakil Khan from Horizon Ventures (which has previously invested early in companies like Facebook, Spotify and Skype) puts it, investors should love “brave business models with disruptive potential – especially in big markets such as the insurance industry”.

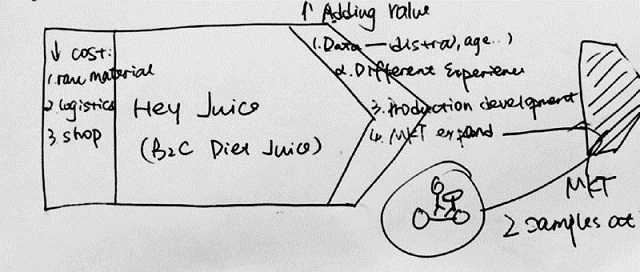

6-4 De Halve Maan: Hey Juice, Hey Beer

It sits in the middle of the Business Model Canvas and it is often the most neglected when brainstorming value-adding innovations. It is the “channels” square. But utilising existing channels better or thinking out new ones can be the source of new business innovations and a lynchpin of a good business model. Think, for example, about what the Coca-Cola Corporation’s distribution networks enable it to do to combat existing and new competitors, or how Tayto’s fine-grained local army of drivers might keep Walkers from dominating the Irish market (see the Taytos case in the previous chapter).

The two stories told below might encourage us to think again about the power of channel innovation at the heart of a business model and they come from opposite sides of the earth. One from a small start-up in Beijing, the other from one of the oldest businesses in a medieval European city.

Bruges has been one of Belgium’s most important centres of trade for over a thousand years and is now a UNESCO World Heritage site. But the growing influx of tourists into Bruges’ cobblestone roads and beneath the spires and ancient buildings on its narrow streets has added to a congestion that has made it difficult and expensive for many of the traditional craft businesses that tourists come to see to operate effectively.

A 500-year-old brewery called De Halve Mann (The Half Moon) came up with an unusual but effective solution to the problem of how to maintain its existence at its brewery in the heart of Bruges (which is so much a part of its value proposition) while developing a more efficient connection to a modern distribution network: a beer pipeline.

“We wanted to avoid running big expensive tanker trucks running back and forth across the city,” explained Company Director Xavier Vanneste. “We got the idea from looking at other life provisions that run through pipes. Water pipes, electricity pipes, cable distribution etc. So why wouldn’t that be possible for beer?”

The Mayor of Bruges, Renaat Landuyt, was initially sceptical when the plans were first brought to him: the city had never allowed a private company to lay pipes beneath its historic streets. But Landuyt gradually warmed to the idea: “It was important for them [and us] to find [a] solution to the mobility problem because [in the past] if we wanted to work a more modern way we needed to let trucks enter the city, and that is what we don’t like, because it is always a risk for the historic buildings and streets.”

But what about the cost? The pipeline moves over 1,000 gallons of beer an hour from the factory to a new bottling and distribution hub on the outskirts of the city, but it didn’t come cheap. The project cost over 4 million Euros. Who paid the bill?

That’s where another bit of modern, innovative thinking became a part of De Halve Maan’s rejigged business model. The brewery didn’t have the capital, and while the City liked the idea it was not interested in paying for it. De Halve Maan needed some new key partners: so they launched a crowdfunding campaign with a difference. Backers would be rewarded with free beer, for life (although Vanneste points out that the amount of free beer per annum is poured in relation to their capital contribution). More than 500 donors quickly came forward.

So De Halve Maan now have a lot more new stakeholders. And tourists have a new sight to see as they walk through the streets of the city: a transparent manhole cover has been cut into the cobblestones so that passers-by can watch the world’s first beer pipeline in action.

Hey Juice, a Beijing based start-up, is a newer phenomenon. Built to take advantage of Beijing’s fast-growing group of middle-class and health conscious young people, Hey Juice delivers made-to-order fresh fruit and vegetable juices to customers. Everything is channelled directly from the production facility to the consumer by electric scooter – easily the fastest way to move around this traffic-clogged maze of a city of 22 million people.

Working without any shopfront or any middle-man distributors selling to stores keeps costs low, and the data gathered through the company’s WeChat site is enabling it to better predict demand levels with ever increasing accuracy – which is very important given that you don’t want to over or under buy produce that can spoil quickly. When Hey Juice looks like it may have a surplus of certain fruit or veg near the end of the day, messages can be sent to customers informing them of discounts of particular juices to help clear the day’s stock. (Above is a drawing of Hey Juice’s strategy in the form of a simple value chain done by one of our students in a strategy class at Peking University in Beijing.)

But the key to Hey Juices’ success may be the idea of distributing directly from the blender to the customer, via an army of electronic scooters.

6-5 McDonald’s: Dick and Mac’s Tennis Court Modelling

The “Fast Food” business model. It is so commonplace now that we take it for granted. Standing in (hopefully) fast moving queues to grab a meal on the run is such a part of many people’s lives now that it is hard to imagine a time before this was common. Who developed this business model and how?

While the movie The Founder focuses mostly on the character of Ray Kroc, who would take over McDonald’s from original founders Dick and Mac McDonald, there is a fascinating scene early on in the movie that depicts the true story of how the brothers thought through and refined their ideas for a new way of making and delivering hot food that Dick named the “Speedy System”.

Early one weekend morning, Dick and Mac took a group of their employees from their burger stand in California (pictured above), a box of chalk and some measuring tapes to a nearby public tennis court. The brothers, Dick in particular, had for some years tinkered with ways to efficiently make a consistently hot and value-for-money product. But they decided that the best way to figure out the ideal shape of their model was to start with a blank canvas. So they mapped out a section of the court the same size as their kitchen and set to work, drawing out different configurations for the key facilities in the kitchen and how inputs would be carried in and food prepared, cooked and served by employees.

On the court, the team rehearsed each part of the cooking process and how they would work together, employees miming how they would work with one another and their instruments almost like a symphony. Meanwhile, Dick sat up in the umpire’s chair taking notes before climbing down to bark a new instruction or redraw some part of the process.

In an interview with The New York Times, the film’s director, John Lee Hancock, explained that he hired a choreographer and a metronomic “click track” to help the actors get into the rhythm of the scene, even though no actual dancing is involved. “She [the dance instructor] would adjust the clicks we needed to get the right up and down beats of the choreography to help with the beats of the scene.”

Asked how he came up with the idea of filming the scene in this balletic way, he said: “I wish I could take credit, but it actually happened this way.”

The actors also became immersed in the reality. Hancock began by directing Nick Offerman and John Carroll Lynch (Dick and Mac respectively) to just ad-lib and get to work after they had the art department come in to chalk out the kitchen layout. But after a while Carroll Lynch said: “We’re the ones who did it, right? We should put the chalk down.” So they jumped right in, rolled up their sleeves and went to work just like the McDonald brothers did. This helped them get into the process of developing an innovative approach to business in a more involved and convincing way. (You can see the article and the movie clip at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/19/movies/john-lee-hancock-narrates-a-scene-from-the-founder.html.)

The chalking at the tennis court helped the brothers confirm some of the things they had thought, disconfirm others, and provided them with a few new insights as well. It helped them map out the McDonald’s Speedy System that Kroc would later take to the world through his aggressive franchising programme.

And the rest, as The Founder movie and any fast food restaurant chain now shows, is history.

Writing your own “business model advantage” case

Writing your own “business model advantage” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “The Mini Case” and “The Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and this is a good vehicle for that purpose. There are also a large number of websites that highlight interesting organisations that you might want to find out more about. For instance:

- Websites for national newspapers

- Forbes

- TechCrunch

- uk.businessinsider.com

- www.fastcompany.com

- www.huffingtonpost.com.

It is also worth noting that in the UK there is an excellent website for company information at Companies House. The address is https://beta.companieshouse.gov.uk/.

If you have attempted to write your own case for Chapters 4 and 5, you may now be in a position to try to identify the key components of a business model. By drawing these as nodes on the paper below you can begin to try to “connect up the dots” into a business model. You should use the directions within this chapter to focus on key aspects. Once key aspects of the model are identified and linked together you should have created a compelling logic of how your organisation’s business works and competes in its markets.

![]()

Notes

- 1. Mikhalkina, T. and Cabantous, L. (2015) Business model innovation: How iconic business models emerge, Business Models and Innovation, Advances in Strategic Management, 33: 59–95.

- 2. Teece, D. J. (2010) Business models, business strategy and innovation, Long Range Planning, 43: 172–94.

- 3. E. H. (2013) Why have containers boosted trade so much? The Economist, 22 May, www.economist.com.

- 4. Teece, D. J. (2010) Business models, business strategy and innovation, Long Range Planning, 43: 172–94.

- 5. E. H. (2013) Why have containers boosted trade so much? The Economist, 22 May, www.economist.com.

- 6. Teece, D. J. (2010) Business models, business strategy and innovation, Long Range Planning, 43: 172–94.

- 7. Baden-Fuller, C. and Morgan, M. S. (2010) Business models and models, Long Range Planning, 43: 156–71.

- 8. Mintzberg, H., and Van der Heyden, L. (1999). Organigraphs: Drawing how companies really work, Harvard Business Review, 77: 87–95.

- 9. Magretta, J. (2009) Why business models matter, Harvard Business Review, May: 86–92.

- 10. Baden-Fuller, C., MacMillan, I. C., Demil, B. and Lecocq, X. (2008) Call for papers for the Special Issue on Business Models, Long Range Planning.

- 11. Casadesus-Masanell, R. and Ricart, J. E. (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics, Long Range Planning, 43: 195–215.

- 12. Hindle, T. (2009) Just in time, The Economist, 6 July.

- 13. Chesborough, H. (2010) Business model innovation: Opportunities and barriers, Long Range Planning, 43: 354–63.

- 14. Baden-Fuller, C., and Haefliger, S. (2013) Business models and technological innovation, Long Range Planning, 46(6): 419–26.

- 15. Zott, C. and Amit, R. (2010) Business model design: An activity system perspective, Long Range Planning, 43(2): 216–26.

- 16. Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010) Business Model Generation, John Wiley & Sons.

- 17. Amit, R. and Zott, C. (2001) Value creation in e-business, Strategic Management Journal, 22: 493–520.

- 18. Saebi, T., Lien, L. and Foss, N. J. (2016) What drives business model adaptation? The impact of opportunities, threats and strategic orientation, Long Range Planning, doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2016.06.006

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Teece, D. J. (2010) Business models, business strategy and innovation, Long Range Planning, 43: 172–94.

- 21. Casadesus-Masanell, R. and Ricart, J. E. (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics, Long Range Planning, 43: 195–215.

- 22. Ibid.

- 23. Mikhalkina, T. and Cabantous, L. (2015) Business model innovation: How iconic business models emerge, Business Models and Innovation, Advances in Strategic Management, 33: 59–95.

- 24. Casadesus-Masanell, R. and Ricart, J. E. (2010) From strategy to business models and onto tactics, Long Range Planning, 43: 195–215.