10

Leading Strategic Change

Wisdom lies neither in fixity nor in change, but in the dialectic between the two.

Octavio Paz

Founded in 1934, FujiFilm is a Japanese success story with 2016 revenues of Yen 2,492.6bn (US$22.0bn) net income of Yen 137.1bn (US$1.2bn) and employing nearly 80,000 people. In the 1990s, FujiFilm had a near monopoly of the Japanese photo-film market in the same way as its rival Kodak dominated the US market with 90% market share in photo film and 85% share of camera sales. Indeed, Kodak was rated as one of the world’s most valuable brands at the time and employed 144,000 people. However, a tsunami hit the industry with the arrival of digital technology. Although Kodak invented the digital camera, by 2012 it had failed to transform, filing for bankruptcy on 19 January, while Fujifilm was able to implement organisation change and survive. Why is it that two direct competitors in the same industry, with near monopolies in their markets, experienced quite different outcomes? Why has one survived and the other collapsed?

The world is in continual flux and organisational adjustment will, of necessity, involve managing some degree of change to structures, technologies, products, services, culture and processes. But over the past two decades the flow of change that organisations have sought to keep pace with has increased dramatically – to the point, indeed, where commentators like Christopher Bartlett and Sumantra Ghoshal have claimed that the levels of change have in many instances outpaced the human capability to cope with change.1 While organisations must move to keep pace with a changing environment, the strategist must also ensure constancy and consistency with regard to maintaining the trust and confidence of key stakeholders (as we outlined in Chapter 1) and with regard to protecting key resources and relationships that have taken decades to develop (see Chapter 5) and which could easily be damaged in a careless transformation. The strategic change management challenge therefore requires ensuring both movement to match developments in the environmental, industrial and competitive context and stability with regard to critical capabilities in optimal measure. As the quotation from poet Octavio Paz at the head of the chapter puts it: perhaps the biggest challenge that any leader of an organisation faces is to create a positive and fruitful dialogue with staff and other stakeholders about what must be fixed, protected and nurtured and what must be transformed.

There are a large number of ideas and frameworks to deal with guiding change. These can be divided into two camps: conventional or straightforward “one best way” methods (these generally are expressed in what are called n-stage linear models made up of key steps), or frameworks that promote more nuanced or differentiated approaches. This chapter reviews what we believe to be the most useful of these models and frameworks. Then, it concludes by outlining the leadership challenge for those who seek to effectively guide organisations through the choppy waters of current and future business and social environments.

Conventional Intervention Models for Leading Change

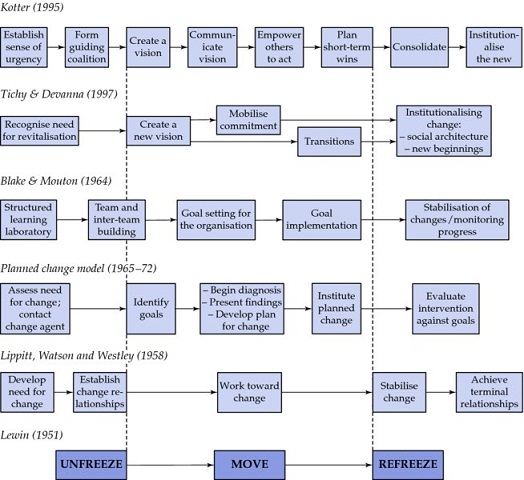

Despite a great expansion in numerical output, we find significant similarity among conventional approaches to managing change. This can be seen by the way that John Kotter’s method, currently the most widely used framework for managing change, replicates most of what has been said in applied management fora on this subject.2

Kotter claimed that a successful change process goes through a series of eight steps of change (see top of Figure 10.1). The first is to establish (1) a sense of urgency, as why would an organisation want to change otherwise? Therefore, identifying a crisis that the organisation must deal with or a compelling opportunity that should be seized is important. Then it is necessary to (2) form an influential team that is credible and will get buy-in from participants in order to coordinate and communicate change; (3) a vision then needs to be developed so that participants know where the organisation is headed and how that will be different to the past. The vision needs to be (4) communicated effectively, which means frequent, rich and powerful communication that continuously reemphasises the vision and need for change. This might be achieved through walking the talk and leading by example. It is important then to (5) empower others to act on vision, by removing barriers to change and recognise and reward people for making change happen. Participants can be energised by (6) creating short-term wins. (7) Gains should then be consolidated and further change achieved as there is a risk that victory can be declared too early. Therefore, it is important to keep looking for improvements and setting goals to maintain momentum. Finally, the new approaches need to be (8) institutionalised by explaining how connections between new behaviours and organisational success work. Explanations need to continue until old habits have been replaced. Other commentators may have outlined their ideas about managing change in other ways, but they are easily assimilated into Kotter’s steps (see Figure 10.1).3

Figure 10.1 The incremental development of conventional change management frameworks since 1950

(Source: Cummings, 2002)

The main reason for the homogeneity of conventional change management theories in the 1980s and 1990s may be history. In the early 1950s, Lewin discovered what textbooks to this day call the three basic steps that summarise what’s involved in the process of changing people and organisations: unfreezing → moving → refreezing.4 Figure 10.55 shows how others (all the way up to Kotter in the mid-1990s) would subsequently follow Lewin’s lead, building on his classical approach, adding details or splitting levels but maintaining Lewin’s three simple steps. This homogeneity is underpinned by a number of assumptions about change:

- Change is a generalisable linear input → process → output process: hence we can determine “one best way” approaches to it.

- Change comes from the top or outside in and then works its way down. In Kotter’s (1995) words, top people must first provide a vision for change.

- We can break down the complexity of change into its “component parts” that can then be ordered into a series of steps.

- Change and constancy are seen as an either/or choice: conventional approaches would have difficulty comprehending the quotation by Octavio Paz at the head of this chapter.

While almost all of the authorities mentioned above and in the related notes are American, Kotter’s eight steps seemed to also chime with the best of European theory. Pettigrew and Whipp’s Managing Change for Competitive Success presents ideas very similar to Kotter’s eight steps. In a study of competitive change in a number of UK industries, Pettigrew and Whipp identified nine key aspects: (1) building a receptive context for change, legitimisation; (2) creating a capacity for change; (3) constructing the content and direction of change; (4) operationalising the change agenda; (5) creating a critical mass for change within senior management; (6) communicating the need for change and detailed requirements; (7) achieving and reinforcing success; (8) balancing the need for continuity and change; and (9) sustaining coherence.6 Of these nine steps, the only thing that the American works generally do not incorporate is the notion of “balancing continuity and change”.

All of these straightforward general models can be used effectively to develop and communicate change programmes. However, we can now see them as somewhat similar in their underlying approach as they are based on the same foundation. And, given that recent research has shown that Lewin in fact never developed or advocated the three-stage intervention model attributed to him (see Figure 10.2 and follow the link to the animated video described below that outlines this research), we should be encouraged to look at additional frameworks that may inspire us to think differently about leading strategic change.

Figure 10.2 Unfreezing change as three steps – watch the video at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iJfdmT1UtBY.

Based on Cummings, Bridgeman and Brown (2016).

Newer (and More Nuanced) Frameworks for Guiding Change

The frameworks for guiding the management of change outlined in the section above are both useful and heavily used. They are used because they are simple, easy to remember and easy to communicate. However, often, managing change is not so straightforward. No two change initiatives are exactly the same and the following differences are worth investigating:

- Change occurs at different organisational and conceptual levels

- There are often different needs and objectives that organisations are seeking to achieve and subsequently different styles of crafting change

- Change can be instigated by different types of individuals or groups

- Change initiatives meet with different forms of resistance that the skilful strategist will want to take account of

- Finally, human nature and capabilities require that change be combined with continuity, to different extents, depending on the circumstances.

These complexities, which require good managers to take a more dextrous or nuanced approach, rather than just implementing an eight- or nine-step plan, are explored in more detail in the sections that follow: understanding that different levels of change require different leadership approaches; that different change needs require different leadership styles; how strategic change can be led from different parts of an organisation; and how leaders can face different forms of resistance to change, and what to do about these.

Different levels of change

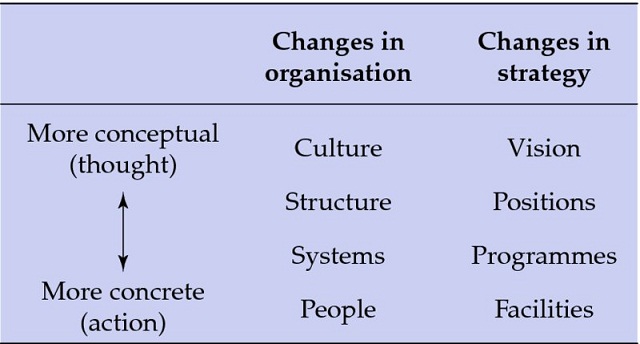

Change can occur at different conceptual or practical levels. Mintzberg and Westley’s framework (see Figure 10.3) provides a useful means of separating out, and seeing the interrelationships between, the more organisational versus the more strategic aspects of change and relating these to different levels of thought versus action.7 For example, changing an organisation’s vision for the future will necessitate changing the organisation’s culture if this new vision is to be achieved, all of which will require a lot of conceptual work. This should then trickle down to more practical, but congruent, actions relating to the organisation’s facilities and people or human resources to ensure consistency of corporate identity.

Figure 10.3 Strategic changes related to organisational changes

(Source: adapted from Mintzberg and Westley, 1992)

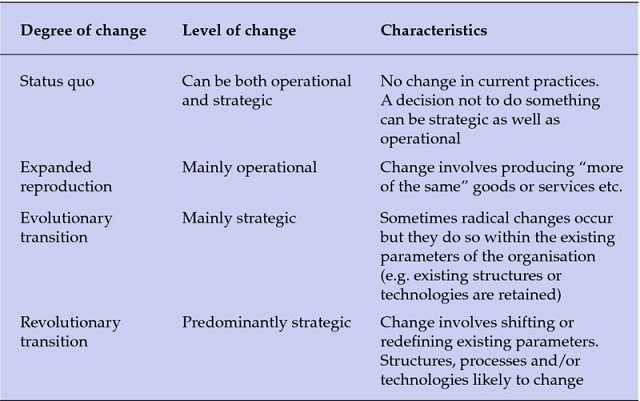

It can also be useful to develop a clearer understanding of whether what is envisaged is a more strategic- or more operational-level change, and what differences of approach this might necessitate, before embarking on the change. For this purpose, David Wilson’s framework, pictured in Figure 10.4, is very helpful.8

Figure 10.4 Levels of operational and strategic change

(Source: adapted from Wilson, 1992)

Different change needs and styles

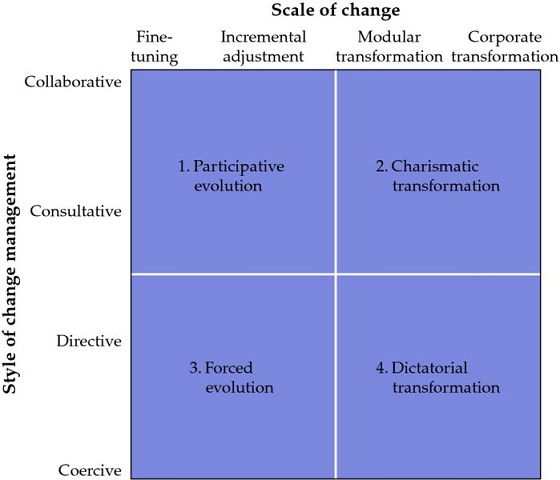

Different organisations in different settings have different needs for change. For example, organisations in industries or societies that are undergoing fundamental changes may require a complete revolutionary transformation, a change programme that is broad in scope, necessitating sharp changes to most if not all of its procedures. In an extreme form, where an organisation is facing collapse, its turnaround would necessitate revolutionary change – a complete rethinking of the nature of the business, its purpose (see Chapter 1), how it competes, and radical and immediate surgery for survival.9 For instance, top management will be highly directive and focus intensively on cash management and short-term actions to reverse losses. These may include disposals, laying off staff and cutting back on investments with long-term payback. In this crisis situation, the strategic horizon is measured in months and as a style of change it might be described as “Dictatorial Transformation” (see Figure 10.5). However, if there is more time available and the organisation in question is in more robust health, top management can be more consultative or even collaborative in identifying how the organisation should evolve. This type of change will require strong visionary management to win over interest groups and might be described as “Charismatic Transformation” (see Figure 10.5). In a calmer setting or a more conservative industry, evolutionary transformation, with some fine-tuning to just a few aspects of the organisation’s activities, will be more appropriate. This may still take the form of imposed change, with a very directive management style, and is termed “Forced Evolution”. With a much longer strategic horizon, far more time can be spent figuring out what to do and negotiating outcomes. This style is termed “Participative Evolution” and depends upon building consensus between varied stakeholders. Figure 10.5 provides a useful means of characterising different change needs and then thinking through the sort of management approaches and programmes required to satisfy those needs.10

Figure 10.5 Different scales and styles of change

(Source: adapted from Dunphy and Stace, 1990)

There are four main styles of change:

- Participative evolution is appropriate when the organisation is either “in fit” with its environment, or it is “out of fit” but time is available, and key interest groups favour change.

- Charismatic transformation, led by a popular change agent, is appropriate when the organisation is out of fit, the need to change is urgent and key interest groups or stakeholders support substantial change.

- Forced evolution, driven by a strong leader, is appropriate when the organisation is either in fit but needs minor adjustments or is out of fit and, although time is available, key stakeholders oppose change.

- Widespread dictatorial transformation, imposed from above, is appropriate where the organisation is out of fit, time is short and key stakeholders oppose change.

A particular context where there are varying needs for change is post-acquisition integration. The target company has been acquired but will have different degrees of organisational and strategic fit with the acquiring company and varying amounts of time available for change. Duncan Angwin (2000)11 developed a contingency framework based on post-acquisition change in UK mergers and acquisitions and suggested four types of post-acquisition integration style which resonate with the framework above. These styles were isolation (which would be forced evolution), subjugation (dictatorial transformation), maintenance (participative evolution) and collaboration (charismatic transformation). (The framework was further extended in 201512 – see Chapter 8.) Figure 10.5 can be usefully applied to such situations to indicate appropriate styles of change.

Different cultures can also influence different strategic change styles. For example, American theorists, such as Hamel and Hammer and Champy, have tended to advocate revolution over evolution and strong leaders wiping the slate of the past clean before building things anew to suit current rather than former needs.13 On the other hand, Japanese approaches, such as kaizen, have favoured slower evolutionary or incremental improvements and consensus-driven change.14

Different organisational purposes also affect strategic change styles. So far, we have focused on profit-oriented business with relatively clear objectives and aims – in the Anglo-American context this can be characterised as the pursuit of profit for shareholders. This clarity helps focus during organisational change. However, for not-for-profit organisations with multiple, non-aligned stakeholder pressures, reflecting a diversity of views about the purpose of the organisation (where the customers are not so much the marketplace as the provider of funds), this coherence may not be achievable, raising huge challenges for organisational change. If there is any doubt about the massive complexity and difficulties involved in changing not-for-profit organisations, one only has to look at the agonies of the UK National Health System, the problems of improving state education and the consequences of privatising the national railway system.

Different instigators of strategic change

We tend to associate strategic change initiatives with those at the top of an organisation. While executives and the roles they play do have a large influence on how change is enacted in an organisation, the dextrous manager of strategic change will recognise that change can also be driven by individuals with unique insights at lower levels of the organisation, or by groups or communities rather than individuals.

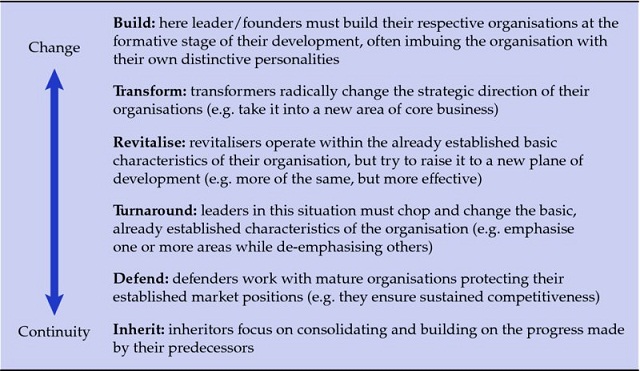

That “managers shape change” seems an obvious statement. However, different managers manage in different ways, and different organisational situations require different styles of change. The Leavy and Wilson scale (shown in Figure 10.6)15 is an excellent means of thinking through what type of management locus will best suit the challenge faced.

Figure 10.6 The locus of influence of leadership related to change versus continuity

(Source: adapted from Leavy and Wilson, 1994)

Perhaps just as often, however, innovative individuals who can see beyond current conventions and practices and create new visions of the future are often the drivers of change. Writers and artists such as James Joyce and Picasso challenged established beliefs and in turn transformed our understanding and appreciation of literature and art. Political figures such as Luther and Gandhi overturned the establishment in similar ways. While it is tempting to think of organisational executives as drivers of change in much the same manner, such figures, in the mould of Richard Branson, for example, are in fact remarkably rare.16 This is probably inevitable. Corporations themselves have become incredibly analytical, seeking to mitigate risk by doubting their hunches, passion and gut feelings and employing sophisticated logarithms to plot their course instead.17 Moreover, the higher up the establishment people are, the less likely they may be to question the very processes that enabled them to get where they currently are. It is important to remember that the likes of Joyce and Gandhi did not employ managerial risk analysis techniques and were nowhere near the top of their fields or societies when they began their transformational quests.

The same is true in business organisations. Often the people with the most innovative ideas, the ones that could really shake up or change an organisation for the better, are not those who have been in senior management positions for a decade or more. For example, it is doubtful that any of 3M’s senior executives would have developed Post-It Notes. Sometimes the best ideas for new products and processes that go on to define an organisation’s future come from research scientists, shop-floor workers, designers or lower-level managers. However, what 3M executives did do was create an environment in which people from all over the organisation had the confidence and systems in place to enable them to contribute innovative ideas that could drive change in the organisation (for more on setting appropriate conditions for innovation see Chapter 8, New Ventures).

Creating an environment where bodies other than executives can drive change is also important when it comes to unleashing the change potential of communities of practice – those informal networks of people that share a common interest. Communities of practice can be powerful drivers of change because they can solve complex problems quickly; they facilitate the transfer of new practices; they continuously develop professional skills and the knowledge base of the organisation; they can help attract and retain new people. The best communities of practice tend to form naturally, but skilful managers can also encourage their emergence. However they come into being, it is crucial that they are supported by an adequate infrastructure. Because they tend to lack the legitimacy and budgets of more formal groups, communities of practice can be vulnerable without this kind of support.

Barriers to strategic change

You might like to refer back to Chapter 5 where the “the cultural web” developed by Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin and Regner (2017) is discussed (see Figure 5.4). One of the strengths of this model is that through identifying the culture and paradigm of an organisation, barriers to change can be surfaced. For instance, certain routines may be very difficult to alter. This can be illustrated by considering the difficulties you might have in trying to do a very familiar task in a different way. For instance, try changing the hand you write with, driving on a different side of the road (in a different country), reversing your cutlery when eating, or playing tennis or cricket with the opposite hand. Normally one experiences an immediate decline in performance before any benefit is apparent and so change is discouraged – you would really prefer to go back to what you were doing before (see Angwin and Urs (2014) for an example of changing routines during an acquisition). There can also be psychological barriers based on how you see the world. We often don’t question these core understandings that are reflected in the paradigm (see the cultural web), but they have a very powerful influence on how we perceive opportunities and threats or strengths and weaknesses for instance.

In our opening example, we wondered why Kodak suffered a catastrophic decline when its direct competitor Fujifilm survived and prospered. One explanation is that they were wedded to the importance of photo film as this is what they were successful at and it had generated vast revenues for them over a long period of time. An influential book, Thinking Fast and Slow (2011), by Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, identifies a range of cognitive biases that distort our perceptions of the world. For Kodak, there were a number of these biases at work, including the “sunk cost fallacy” that legitimated continuing to invest in photo film when the world was rapidly moving away from this product. The reason was that the whole company had invested heavily in the area for decades and did not want to see this investment written off. Cognitive biases and psychology are now recognised as important determinants of managerial decisions and these have led to the rise of Behavioural Strategy. Psychologically, employees would also have had loyalty to the way things were done and what Kodak stood for, which would have been reinforced by the symbols, rituals and stories of the organisation. Also, politically, the power structures would have inhibited change as people’s careers had been built upon the photo-film industry and to entertain a new departure in the activities of Kodak would have opened the door to different power bases and new influential executives. Top executive power would have been reinforced by the organisation’s structures and control systems. Arguably, Kodak also suffered from an out-of-date mentality, that its “razor blade” business model (see Chapter 6) did not work for digital cameras, and that making perfect products was no longer the way forward when the new high-tech mantra was “make it, launch it, fix it”. With a high degree of conservatism in the organisation, that some labelled complacency, there was probably fear of the unknown, of getting involved in something unfamiliar that could have negative consequences to reputation and pride. Linked to this inertia in the organisation was the fact that it was physically headquartered in, and dominated, the city of Rochester, USA, where very little criticism was heard. For these reasons, Kodak would not recognise the threat of digital photography for a long time, or really invest in it with enthusiasm, even when their own company had developed the technology! In a company such as Kodak, with strong barriers to change, how can resistance be managed?

Managing different forms of resistance to strategic change

One of Machiavelli’s most often quoted lines gets to the nub of why many well-planned change initiatives fail: “The innovator makes enemies of all those who prospered under the old order and only lukewarm support is forthcoming from those who would prosper under the new.” Many change initiatives do not gain traction due to failing to anticipate and manage such individual and organisational resistance that Machiavelli’s quotation suggests is inevitable.

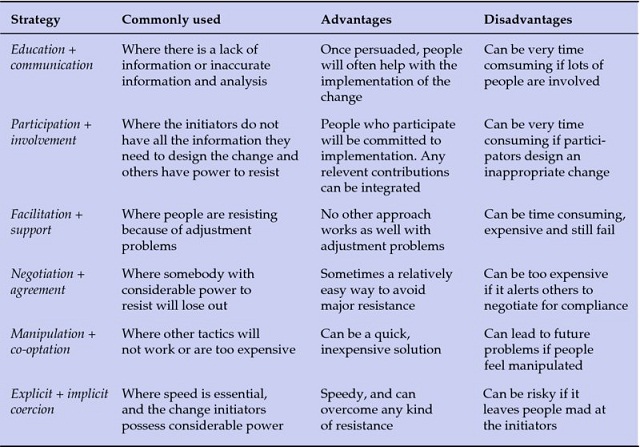

Most of these failures are due to insufficient communication and thus uncertainty about what change is coming, why it is coming and what the implications of the change will be for people (see Angwin et al. 2016 for an example). Kotter and Schlesinger’s table articulates different communication strategies that can be used to work through normal forms of barriers to change, where they should be used, and their relative advantages and disadvantages (see Figure 10.7).18

Figure 10.7 Dealing with resistance to change

(Source: adapted from Kotter and Schlesinger, 1979)

The Strategic Leadership Challenge: Blending Change and Continuity

Leadership is currently one of the “hot topics” in business, and it particularly intersects with strategy where change is concerned. People often ask: “What is the difference between ‘strategic change’ and ‘change in general’”? Our view is that strategic change requires deft leadership that blends and balances a seemingly paradoxical mix of change and continuity. This is true now more than ever before, for two reasons.

First, there are now very few completely bad organisations. Increased global competition has run them out of business or forced them to improve. Almost every company does one or a few things well and these should be built on or surfed.

Second, research now suggests that good employees are having difficulty keeping up with, and are consequently frustrated by, the change programmes that they feel they have no control over. And we know that, these days, companies cannot afford to disengage good people. Despite the need for change, people crave continuity. It is this dialectic – the interplay between forces for consistency and forces for change – that the successful strategist must lead. This reconnects us with that one element of Pettigrew and Whipp’s nine steps for managing change that was substantially different from conventional change frameworks: “balancing continuity and change”. Paradoxically, then, it may be that the most important question with which to begin a strategic change programme is: “what aspects should we preserve and maintain?”

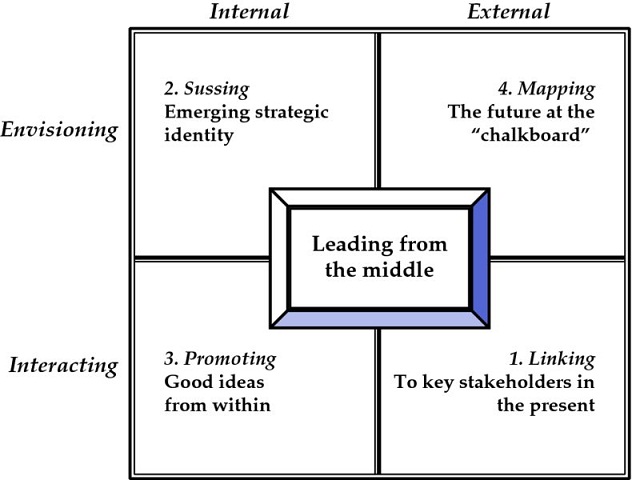

We think there are four new ideas (and associated frameworks) that can help leaders manage strategic change more effectively. The first is the idea that strategic change can be best led not from the front or the top of an organisation, but from the middle.

Leading change from “the middle”

The Strategic Leadership Keypad, outlined in the book Creative Strategy, can be a useful guide in this regard (Figure 10.8). Here the authors argue that, with an increase in the value and power of the engaged “knowledge worker”, leaders of strategic change need to become less “command and control” oriented and be more facilitators, enablers, mentors and coaches. Whereas traditional business, government and military models would see the leader at the top, and the previous chapter made a case for strategy and change emerging from the “bottom up”, Creative Strategy argues that the strategic leadership of change should be positioned at the middle, or in the centre of things, providing a hub for the creative band of brains and networks to latch on to: a gravity that connects and respects the diversity and dynamism necessary for change while ensuring that things don’t spin out in conflicting orbits.

Figure 10.8 The strategic leadership keypad

(Source: adapted from Bilton and Cummings, 2010)

Around this middle, the Keypad distils four key elements for effectively leading continuity and change: linking, sussing, promoting and mapping. Successful leaders of change should be able to “toggle” between the four keys, between inside and outside, past, present and future, between emergence and top-down leadership.

The first key, active or interactive linking with the external environment, means defining who the key external stakeholders are, and being a lynchpin that helps to connect them to key internal stakeholders (see Chapter 1). It also often means being the public face of the organisation, explaining it, promoting it and if necessary defending it. Taking these roles frees the creative minds within to get on with creating value. A. G. Lafley enabled strategic change at Procter & Gamble by clearly defining the key stakeholders that employees and team members respectively should have in mind: customers. He saw P&G’s most meaningful results come from two critical points of contact with the outside: first, when customers choose to buy a P&G product over others and, second, when they use the product at home. Subsequently, Lafley came to see the importance of innovations being born not only in the lab: they should be driven by consumers, or, more accurately, from the interaction between P&G employees and consumers. Hence, almost every P&G office and innovation centre now has customers working inside with employees.19

Second, strategic leaders must be able to step back and envision, or suss, the essence of the organisation: to distil and embody or exude the organisation’s strategic identity. To make the strategy simple and tangible so that people don’t have to spend time wondering whether a new creative idea, development or interpretation can be made to fit, add to or recalibrate the organisation’s strategy – they just know if it doesn’t and get on with it if it does. One of the “signature moves” of Bill Campbell (the guiding force behind many of Silicon Valley’s most creative companies: from Apple to Google to Jasper Wireless) is convincing CEOs to remove, or move aside, a CFO that has become lodged in the centre of things thereby distancing a CEO from the ability to keep their finger on the pulse and thus their ability to know and communicate “the suss” on what their companies are about.

Third, strategic leaders understand the value of stepping in to find and promote good “waves” (emerging ideas, values or people) from “lower echelons” quickly up through the organisation. They know that higher-level employees do not have a monopoly on good ideas, that game-changing practices are likely to come from those not yet inculcated, and that just the sense that good ideas will come from everywhere in the organisation keeps people higher up on their toes and motivates those further down. The Post-It Note example described earlier is a good example of leading change through promotion; as is Billy Beane’s promotion of scramblers and “uglies” at the Oakland A’s, described in the Live Case (10–4) further on in this chapter.

Fourth, strategic leaders must be able to externalise a vision: so as to map the path ahead or provide a picture of where the organisation is heading. This need not be accurate. Things change. The purpose is rather to give confidence about what good movement will look like and lead to, and that momentum will be maintained – even if things don’t emerge as planned. Movement and momentum motivate creative people and make them more ready and able to adjust and change in any event.

These four leadership approaches to getting to the middle (or heart) of an organisation can be informed by systems thinking and strategic stories. These can be supported effectively by Strategy Directors.20

Systems thinking

From the above it is evident that “connectedness” is crucial to how organisations work, and change, effectively. Peter Senge, perhaps the most influential systems thinker to affect how we look at strategy, put this more formally in his book The Fifth Discipline.21 Senge identified five interrelated “disciplines” required to build a learning organisation: (1) personal visions; (2) surfacing the often implicit models currently used for decision-making; (3) developing a shared vision; (4) team learning; and finally (5) the fifth discipline: systems thinking to understand how the relationships and interactions between the elements of the organisation and the environment affect the whole. This systems thinking applied to the leadership of strategic change should entail the following considerations:

- Seeing interrelationships and processes rather than things and snapshots

- Recognising that individual “cogs” are not to blame for poor performance – they can only do what the system allows them to do

- Distinguishing which parts of the system have high impact on strategy and which are only minor details

- Paying attention to (3) and focusing on areas of “high leverage” – the 20% of things that will make 80% of difference (sometimes this is referred to as the 80/20 rule)

- Looking beyond solving symptoms and outcomes through popular quick fixes or applying generic buzzwords – poorly performing systems require systematic solutions.

The power of strategic stories

Human beings can learn by accommodation through two practical means: through being changed by personal experience, or through encountering other people who communicate stories encapsulating other experiences. Given the inherent limitations of personal experience, stories are invaluable for the learning organisation. In the words of Annette Simmons: “When you tell a compelling story, you connect people to you or what you are trying to achieve.” While stories have for some time played a role in conveying complex marketing messages to customers (e.g. the identities of Unilever’s main ice cream brands have been organised around the following storylines for many years: Solero – stories of refreshment; Magnum – self-indulgence; Carte d’Or – sharing), they are now playing a part in the way that many companies think about leading strategic development and can be an excellent approach to leading from the middle.

In 1998, “Strategic stories: how 3M is rewriting business planning” was published in the Harvard Business Review.22 It clearly struck a chord, becoming one of the HBR’s best-selling offprints. In the article, 3M ascribed much of its success to the company’s “story-intensive culture” and how this has changed the way it “does strategy”. 3M attributes its new approach to two things. First, a recognition that traditional bullet points and list-making approaches to communicating strategic plans are too generic, leave critical relationships unspecified and subsequently do not inspire thinking or commitment. Second, a recognition that communicating and developing the same ideas through stories enables people to see themselves and their organisational operations in complex, multi-dimensional ways, helping them to explore opportunities for strategic change and form ideas about future success. “When people locate themselves in these strategic stories,” the authors concluded, “their sense of commitment and involvement is enhanced.”

There are more scientific reasons why stories, or conversations about strategic stories, are important for organisations. Psychologists have established that lists are much harder to remember than stories because of “recency” and “primacy” effects. People mainly remember the first and the last items on a list but not the rest of it. Also, lists enable “selective memory” as people tend to select the individual points that they like and focus on those, forgetting about the whole and the many integrated parts that make this up. This is one of the major limitations of bullet points – they miss out how things are linked together – there is no narrative, no story. Language researchers have found that when they translated history textbooks into the story-based style of Time or The Economist, students could recall up to three times more information. Cognitive scientists have examined how the stories we hear in childhood enable us to imagine a course of action, imagine its effects on others, decide whether or not a particular direction should be taken and plan accordingly.

If a picture paints a thousand words, then a story or an anecdote about a company can connect up a thousand threads and give a corporation a flexible focus that can launch a thousand initiatives that both encapsulate and build core values (see Chapter 6). In the words of Gardner and Laskin, authors of Leading Minds: An Anatomy of Leadership: “Stories of identity – narratives that help individuals think about and feel who they are, where they come from, and where they are headed – constitute the single most powerful weapon in the leader’s arsenal.”23 Tom Peters even has a term for a management style based on this type of thinking: MBSA – “management by storying around”. It is interesting that human beings can communicate and learn an incredibly complex system of meaning through a whole series of convoluted stories, yet be unable to remember a vision statement, code of ethics or list of policy objectives. Maybe this is why societies put so much emphasis on telling stories to children, as they are so powerful in communicating complex meaning and remain embedded in the memory for so long. In a knowledge society, where learning organisations are imperative, many organisations are taking stories seriously. At the time of going to press, a nice example was provided by the Scheaffer company, whose website (www.sheaffer.com/stories/) linked to a number of video clips where customers connected their Sheaffer pens to signature moments in their lives as a way of expressing the company’s strategy of promoting the idea that a “Sheaffer is more than a writing instrument”.

The growing trend towards utilising strategy directors

Duncan Angwin and Sotirios Paroutis have recently argued that Senior Strategy Directors (SSDs),24 sometimes called Chief Strategy Officers (CSOs), fulfil many of the roles necessary in bringing about organisational change by being the missing link in connecting up strategy – from the shop floor to the boardroom. They argue that as organisations need to be strategically agile, able to be nimble and flex rapidly, while also making strong choices and resource commitments over the long term, this places increasing strain upon the connectivity of companies internally and across organisational boundaries.

SSDs act to identify tensions and rifts in order to bridge them through translation and brokering skills. They perform a critical role in providing leadership and necessary structural ties, vertically and horizontally, throughout organisations and with external stakeholders, binding different social networks in a dynamic way to facilitate organisational realignment. In order to succeed as an SSD, impressive social skills and strong technical competencies are key to being a credible strategic leader of change to a wide range of audiences. Effective Strategy Directors can provide support to organisational leaders in taking a strategic approach to managing change.

Referring back to the question of why Kodak and Fujifilm had such different outcomes when they were very similar in their earlier success, we can now see that they approached the need to evolve in different ways. While they both had similar information on the impending tsunami of change, and both showed early resistance to any change, Fujifilm had a more coherent approach to leadership, communication and strategic change than Kodak. While in the early stages at Fujifilm the men in the consumer-film business dominated and refused to acknowledge the looming crisis, just like Kodak, Shigetaka Komori showed great leadership skills in taking them on, communicating a new purpose for the organisation, slashing costs and jobs leading to $3.3bn in restructuring costs, cutting managers, researchers and development labs. Komori knew they had to develop a new business model as the gentle decline anticipated in the photo-film market became a free fall, with photo film’s contribution to group profits going from 60% to zero in a decade. Undoing the work of his predecessors was almost unheard of in Japan. Ironically, some have commented that Kodak acted like a change-resistant Japanese company and Fujifilm acted like a flexible American one. Fujifilm developed new routines with its in-house expertise and found new applications for its film technology in cosmetics, medical imaging equipment and in optical screens for LCD flat panel screens. It built on its core competencies, mastered new tactics to survive and had consistent and persistent leadership. Meanwhile, at Kodak, leadership was inconsistent, with a raft of new CEOs lurching from one initiative to another, communicating many different messages over time and spending billions trying to buy ready-made businesses with little in common with Kodak’s core except the belief that they could sell anything. There was little strategic clarity of purpose. Most of the acquisitions did not work out. Fujifilm’s leadership showed consistency of purpose and clarity in communications whereas the Kodak organisation really did not want to change and the leadership was criticised for complacency.

While it would be possible to relate the change approaches of Kodak and Fujifilm to change frameworks outlined in this chapter, it is important to note that change is often not linear, as the n-step models suggest, and that there are likely to be many feedback loops in the process. We show in this chapter that there also needs to be a blend between the actions taken, and to be taken, and the leadership approach that understands the unique setting or context in which the change initiative must work. In addition, in order to get the most from the organisation, communication plays a key role and leadership needs to be able to communicate a clear strategic purpose that can help stakeholders pull in the same direction – so everyone will know how fixity and change may interrelate.

Leading Change Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

10-1 Pringle: Hanging by a Thread …

Pringle of Scotland is a knitwear company with a long and proud history. Established in 1815 in the Scottish Borders and based around the town of Hawick, its trademark argyle sweaters and golf-wear became increasingly popular in the middle of the 20th century, when it found fans among the early “Sweater Girls” – who included sophisticated leading ladies like Jean Simmons, Deborah Kerr and Margot Fonteyn – and the dapper Edward, Duke of Windsor. However, the later part of the 20th century saw a decline in the company’s fortunes. A perceived “stale-ness” of the brand and falling sales saw a company that once employed 4,000 people in the region shrink to a quarter of that size. In June 1998, a further 720 jobs were shed with the closure of two factories in Scotland. With just 200 employees left at the Hawick factory, and Nick Faldo seemingly entrenched as Pringle’s poster-boy for the past 20 years (a good golfer but hardly a fashion icon any more), many feared that Pringle was not cut out for the modern world of business. The company was put up for sale.

Kenneth Fang of SC Fang & Sons, a Hong Kong Knitwear manufacturer, bought Pringle in March 2000 and immediately poached a young manager from Marks & Spencer’s to head up the company. Kim Winser was responsible for trebling the turnover of aspects of M&S’s clothing business, but she recognised that Pringle presented a much tougher challenge.

On a positive note, however, the recent post-modern love affair with things retro has seen the successful resurrection of a number of “former glories” like Pringle. For example, Daks – the label that introduced the first self-supporting waist-band for women’s trousers – has adapted its style to changing times. Recently, the label invited fashion students from the Royal College of Art to give it a 21st-century makeover: with the proviso that its trademark shades of camel, vicuna and black were kept to the fore. LVMH, whose portfolio includes brands such as Dior, Givenchy and Louis Vuitton, has gone from strength to strength under the impressive Bernard Arnault. Burberry is another label that has enjoyed a renaissance after new managers and new designs were introduced in 1997, and successful diversifications were made into other product ranges. Since then, celebrity devotees have helped regenerate Burberry’s image.

Indeed, the recent craze for all things vintage has given such companies an inimitable source of advantage: an ability to recreate their iconic lines. Boucheron, the haute jewellery company, launched its Vintage Limited Edition collection in 2002, re-releasing designs from the 1970s. Its Creative Director, Solange Azagury-Partridge, plans to add vintage pieces from the 1980s in the next few years. “Boucheron is 150 years old and has a really rich archive, with pieces that are so great and so appropriate that it is a shame not to revisit them again”, she says. However, this new trend to revisit the old is not simply about scoring some quick sales; it is also a clever external marketing and internal strategy initiative. Azagury-Partridge points out that “reissuing pieces from the past is a way of conveying the essence and character of the brand”. In other words, it is an “event” that can create a buzz and whip up enthusiasm for customers jaded by the homogeneity of global shopping, while raising awareness of what the company stands for and the standards it is trying to achieve and maintain.

However, there seem to be just as many failures as success stories with attempts to rejuvenate luxury brands. Since fading into obscurity in the 1980s, Jaeger has made repeated attempts to update its image by redesigning product lines and ranges. However, these attempts did not win enough new customers and traditional followers felt alienated. Shares in the cash-strapped Luxury Brands Group, which owns the Hardy Amies brand, were recently suspended because of a takeover bid and shares in Printemps-Redoute, the French retailer that is the majority owner of Gucci, fell over 50% in the first half of 2002. Prada, the fashion house, has had to cancel its float three times for fear of a poor response from the market. The effect of September 11 and wealthy tourists staying away from Europe has been blamed for adding to the struggles of smaller businesses of a similar ilk. Dawson International, the cashmere company, issued profit warnings in 2002 at about the same time as Chester Barrie, the Savile Row tailor, had to call in the receivers. Even traditional stalwart Fortnum & Mason, the “Queen’s grocer”, which was privatised in 2001, is fighting for its life. It has frozen staff pay and been forced to open its doors on Sundays – something previously unthinkable – in an attempt to revive its fortunes. Managing Director Stuart Gates told staff: “The company has to face hard decisions critical to the future of the store.”

Maceira de Rosen, an analyst at JP Morgan, says that the luxury goods labels that remain intact will be those that have a strong brand that is “balanced geographically, whose sales are spread over regions, like Burberry. It also helps to have good management with experience of tough times and capable of flexibility in terms of cost-cutting.”

So, what has Kim Winser overseen in her first two years in charge at Pringle? She began by finding out, and then explaining, just how dire the situation was. She characterised her own and her staff’s task as “[r]escuing the heritage of a great British brand”.

Following this she instigated an aggressive trimming of existing product ranges (out went lesser-quality lambswool jumpers and underwear, for example). “We only make beautiful cashmere knitwear”, she explained. She then sought greater efficiency in the Hawick factory. The potentially infinite number of different Pringle jumpers on the market – a function of allowing some retailers to order alterations to colours, buttons and sleeve lengths – has been discontinued, with Winser claiming that “we must have one very clear range, one message, which must not be broken. If people don’t like our sleeves or our buttons I suggest that they don’t buy Pringle.”

While a strategic decision has been made to continue and invest in the factory in Hawick (at a time when so much manufacturing is being relocated out of the United Kingdom to the Far East), the existing Factory Manager was relieved of his duties. Winser promoted a younger more energetic character from the floor to take his place and then worked closely with him to improve processes and facilities.

While the previous Pringle design team was retained, new blood was also injected. The first collections under Winser’s reign showed a heavy emphasis on updating the signature argyle knits and promoting the traditional Pringle Lion logo in interesting new ways. The new head designer drafted in to breathe further life into Pringle’s venerable history is Stuart Stockdale, a 33-year-old with diverse credentials. Stockdale graduated from Central Saint Martins in London before completing an MA in womenswear design at the Royal College of Art. Since then he has covered both ends of the fashion market, working as assistant to the Italian designer Romeo Gigli before cutting his teeth in commercial design with J Crew – purveyor of basic casual wear to the US masses. This experience gave him a great understanding of the American market – a market that is crucial to Winser’s plans for resurrecting Pringle. Since returning to the UK, Stockdale has set up his own label in London as well as launching Jasper Conran’s first luxury menswear collection. Now he works for Pringle. “When I first saw the archive, I was totally inspired,” Stockdale claimed. “There is so much potential. There was nothing else like Pringle on the market. My challenge is to break out from the knits, yet everything I design must come from the heritage of the knitwear.” Stockdale is well placed to understand what he is taking on. He was born just a stone’s throw away from Pringle’s Hawick home.

Winser set her staff tough targets. Within 12 weeks of her joining the company, she reversed a previous decision not to show a new Pringle range at the world’s biggest menswear fair in Florence, and soon after this wanted to launch completely new menswear and womenswear ranges in Pringle’s first live catwalk shows since the 1950s. While it was a close-run thing, both targets were met successfully, providing a tremendous boost to staff morale.

Nick Faldo has been removed as the personification of Pringle’s identity (although he has been retained to promote golf-wear in certain markets). David Beckham has been identified as an appropriate update of Faldo, and American anglophiles such as Madonna and Julia Roberts reinforce his British presence. The aim of these changes is to refocus the company identity around an “old-world take on modern elegance”.

Pringle’s London headquarters has been moved from Savile Row, which Winser saw as too fusty and not fashion-oriented enough anymore, to a setting described as “retro-chic” – a converted 1960s warehouse just around the corner. A new emphasis on retailing has been signalled with Pringle “signature stores” being developed in Milan, New York, Tokyo and London. The latter will replace Emporio Armani’s flagship store in Bond Street. Bill Christie, who played a significant part in the successful regeneration of Burberry, has been employed as the new head of retail. Mr Christie is promising VIP customers complimentary single malt Scotch whisky in the “libraries” within these stores, where the men’s range will be displayed.

The signs, so far, are positive and Winser is proud to communicate the company’s recent achievements. Sales are up by a third. Many new high-fashion retailers are now buying Pringle. The number employed in Hawick is up by a quarter. The American market is still tough, but Winser claims that Pringle is not suffering like some and that “we’re well placed for when things pick up”. It is speculated that Winser has even begun to cast her eye over some of Pringle’s traditional competitors (like those mentioned above) which have fallen on hard times, but she claims to be holding back at the moment: “I think it’s best to focus on [the brand that] we have already.” However, new international licensing deals are now enabling Pringle to take the label into related diversifications such as leather goods, children’s clothes, and home-wear and increase production quickly and effectively.

The Sunday Times has described Pringle’s progress as “a great British success story”. Winser herself is more circumspect: “Is the company saved? Not completely. But we’ve made a very good first step.”

Postscript: after leading change at Pringle, Winser was brought in to do the same kind of job at Aquascutum, leading some to dub her the “turnaround Queen”. Winser was awarded an Order of the British Empire (OBE) by the actual Queen (of England) for services to the fashion industry and launched her own fashion brand Winser London in 2013.

Some suggestions

Some suggestions

- While the effective leadership of change will require an understanding of the particular organisation in question, this case seems to suggest at least one general characteristic in this sector. It seems important to be very cautious about revolutionary change because a luxury brand often relies on a mystique created by its associations and relationships with the past – and this must be preserved at all costs. Often the guardians of these relationships are long-serving staff or suppliers or customers, so they must be treated with care. However, often these organisations have fallen out of fit with the modern business environment, and subsequently on hard times, by not questioning old processes, inherited inefficiencies or outdated production methods. Managing change in this sector appears to require a very dextrous change agent who can effectively blend evolutionary and revolutionary approaches, going through each item of the value chain, asking what should be preserved and what should be changed, and asking if every item does actually contribute to a great enough extent to justify its costs.

- To begin, Pringle is probably in the revitalisation category. As the case goes on, Pringle moves down the Leavy and Wilson scale toward requiring an increasing emphasis on continuity and a lessening emphasis on change. Correspondingly, Winser combines Revitaliser, Turnarounder, Defender and Inheritor loci.

- One can quite easily break down Winser’s success using a straightforward change framework like Kotter’s eight steps. Using this we can see that Winser:

- Emphasises the urgency of the situation

- Works hard to form coalitions (with the existing design team and the new Factory Manager, for example)

- Expresses a clear vision, both in word and in deed

- Communicates the change with everything she says and does

- Sets tough targets and then lets people get on with achieving them

- Uses these targets, once achieved (e.g. the fashion shows), as exemplars of short-term wins

- Communicates to consolidate these successes

- Recognises that the current success is just a start and that there is more change to come.

However, this sort of analysis only tells part of the story. As the ideas for the previous question suggest, managing change in this sector requires a dextrous approach that blends different types of evolutionary and revolutionary methods. In this light, it is interesting to look at how Winser exhibits a number of different change management styles in this case. For example, she exhibits a number of Dunphy and Stace’s four change styles at different phases, and on different issues, when appropriate (as is often the case, new leaders can take advantage of the uncertainty and new opportunities that a change of leadership brings to start out more dictatorial and move toward more participative styles). Consequently, she also uses different strategies to manage resistance.

She seems to focus strongly on the importance of consistency across the operational and strategic levels, and the culture and the strategy of the organisation, to preserve the corporate or brand identity. Moreover, in terms of the strategic leadership keypad, she identifies buyers as the key lynchpin to the outside and seeks to improve relations here while not allowing buyers to customise items and hence dull the key identity that she has sussed (e.g. “Rescuing the heritage of a great British brand”; “We only make beautiful cashmere”).

Her deeds here are backed up by promoting certain pre-existing aspects and stories from below: the Scottish/British heritage; sporting/aristocratic traditions through bringing forward the likes of David Beckham and Madonna; the traditional argyle; the promotion of the new factory manager from the floor; and her clear mapping of a more positive future of building upon the traditional knits and getting to new customers. And Winser seems very adept at focusing on the 20% of the business that will make 80% of the difference in leading change, going forward.

Finally, she acknowledges that the change programme is not over. No matter how successful these early steps have been, they are still first steps on a long onward journey.

![]()

10-2 Reliant: The Plastic Pig

During the 1970s, Reliant was the second-largest independent British producer of cars in the UK, with 360 cars a week coming off its production line. Reliant was noteworthy for the three-wheeled Reliant Robin as well as the up-market sports car estate, the Scimitar, once favoured by Princess Anne. The three-wheeled Robin consisted of a fibreglass body and an 850cc aluminium engine capable of 60 miles per gallon, all of which was made in-house.

After a long period of decline, Reliant went bust three times during the 1990s. (A brief history of the firm and its cars can be found on www.3wheelers.com/reliant.html.) While in administration, Jonathan Haynes, an ex-Jaguar engineer, decided to attempt a rescue of the ailing firm. Haynes’s father had been famous for designing the E-type Jaguar, a famous racing car, and the son, like his father, also had a passion for sports cars. He was attracted by Reliant’s illustrious past even though sports cars hadn’t been made since the early 1990s. Just before Reliant entered administration, the firm was only producing the Robin, which had been dubbed “the plastic pig”. To get the factory working again, Haynes would have to focus on production of the Robin and postpone any thoughts of a more glamorous future. How could he possibly turn the tide?

On arriving at the site, he found total disarray as the administrators had left the site in a real mess. The machines had lain idle and had seized up and rusted. One employee commented that it was a good collection a museum would be proud of. Haynes’ first task in getting production restarted was to hire back the original engineers, as they knew how to make the Reliant Robin. It was a testimony to their loyalty to the car that they even considered this very uncertain future.

Suppliers proved very awkward. They had lost money when Reliant went into administration. Even for such small items as bulbs costing 10p each they wouldn’t supply until Reliant’s cheque was cashed. There were other demands on working capital as well. Employees needed to be paid and, to get production moving as soon as possible, Haynes had to pay for large amounts of overtime.

Reliant Robin customers are passionate about their cars. Around 44,000 were registered and many had bought seven or eight cars over a sustained period of time. The Reliant Robin had a strong image at the time, as it featured in a favourite BBC comedy, Only Fools and Horses, and was also the object of many jokes by the comedian Jasper Carrott. Although laughed at for its quirkiness and down-market image, many also regarded the Reliant Robin fondly – indeed, the jokes were seen as free advertising. Part of the attraction may have been the unusualness of a three-wheeled car, and the camaraderie of an ownership club. The car was certainly popular among market traders and farmers. The loyalty of the customers meant a continuous demand for spare parts and updates, although many competitors were filling this demand.

Haynes forecast that the firm had to build 50 cars per week to pay his rehired 60-strong workforce and to balance the books. Fortunately, when he took charge, he had discovered 14 Robins in nearly complete form. With little effort these cars were finished and sold.

One of Haynes’ early priorities was to meet with the dealers to hear their views on what the customers wanted. Throughout the first year, Haynes was close to the dealers, but also demanded quick and prompt payment from them.

At the factory, he placed a salesman into a position that he regarded as the most important in the firm – to sell off spare parts to generate £2,000 per day. This target was soon doubled. In his words: “Sell anything! Sell, sell, sell!”

Haynes was conscious that traditional attitudes in the company had to change. Many employees had lived through the previous three collapses and were very cynical that anything would really change. In the day-to-day operations of the business, Haynes detected the attitude of “The answer’s no, but perhaps we can do it, but the answer’s no!” In response, he would quote John Neil of Unipart: “The answer’s yes – now what’s the question?”

Haynes was worried by his 20 employees involved in making the bodies of the car, entirely by hand. This seemed overly labour-intensive and outdated, as chopper guns existed which could do the task more quickly and would require fewer employees. In forceful discussions with his production manager they agreed to test out the new technology.

Haynes underachieved his target of 50 cars per week, producing 36 cars at the deadline. Reasons included reliance on new employees who had to be taught the job. However, support from Haynes’ backers continued. A special edition Reliant Robin was launched in racing green and was well received by customers. At this time, Haynes also hired a designer to draft images of a new sports car.

At the end of the first year, Haynes relaxed at his farm and reflected on the trials and tribulations of his first year. At one stage, they had almost come close to bankruptcy, with just £400 in the bank. He had pushed all his employees hard with long hours, tough discussion and with only the promise of an uncertain future. Indeed, his own farm had suffered as he put all his attention into Reliant. However, it seemed now that Reliant was back onto a firm footing and Haynes savoured the prospect of the unveiling of his new four-wheeled sports car at the Birmingham motor show the following month.

10-3 Church(es): Three in One

The new vicar of St. Margaret’s rose to address the assembled congregations of St. Margaret’s, St. Barnabas and Trinity church.

- St. Margaret’s vicar:

- “I’m pleased to see so many of you here this afternoon to discuss the future of our three churches and how we may move forward as a unified body. Our churches already work together in a number of ways, such as a shared parish newsletter, occasional shared services and the rotation of priests on a bi-monthly basis. This is very much in the spirit of the Church of England’s wishes that ecumenicalism, the working together of different branches of Christianity, is the road we must follow. When I was appointed to my position at St. Margaret’s, it was made clear to me by the bishop that we must embrace our differences as a source of strength. With this vision in mind, we must also confront the practical challenges of everyday existence in our parish. Our congregations are ageing and dwindling and we have very significant costs in the upkeep and running of three church buildings. We are also expected to increase our contributions to the diocese from our collections and bequests. The vicars of St. Barnabas and Trinity have had many meetings on this subject and this evening are proposing that we consider worshipping more closely together under fewer roofs. This will also have the welcome effect of reducing our costs.

As you know, St. Barnabas’s is a Grade I protected listed building25 and so cannot be changed in any way. The focus of attention is therefore on what we should do with St. Margaret’s and Trinity church. Trinity is located on the main street of our town and a large number of people pass daily. Local interest is evident in the very successful coffee mornings held on Saturday. However, Trinity is in very poor condition and will need a complete restoration in the next few years or a rebuild – I believe some architects have been contacted informally and they recommend the latter course of action. Needless to say either course is very expensive, even taking into account the subsidy we may receive via the bishop. St. Margaret’s is a very large Victorian building with a seating capacity of 700. It is less well located, being set in attractive memorial grounds, in a quiet leafy side road some way from the town centre. Apart from regular Sunday morning services, its large seating capacity makes it attractive to local schools for their special events. St. Margaret’s size is also a drawback as the older members of the congregation complain that it is cold and there is no doubt that it costs a lot to heat.

I would now like to ask all of you for your thoughts on how we might go forward in realising our aims of greater ecumenicalism, and reducing our costs.” - Trinity church’s vicar:

- “Thank you for your opening words, vicar. I would like to suggest that the forces of St. Margaret’s and Trinity combine to create a stronger, unified congregation. I believe either church would be large enough for this to happen. The arguments for making Trinity our preferred option are its excellent location and it could be rebuilt to be a striking new presence on the high street. St. Margaret’s, on the other hand, could be redesigned to suit the needs of an enlarged pluralist congregation.”

- Congregational member of St. Margaret’s:

- “When you say ‘redesign St. Margaret’s,’ what do you mean exactly?”

- Trinity church’s vicar:

- “Well, our style of worship at Trinity is more intimate than that of St. Margaret’s. We prefer a more conversational style in smaller spaces, rather than the, dare I say it, ‘pomp and splendour’ of the high church style of St. Margaret’s. I would like to suggest that architects are employed to see how St. Margaret’s could be partitioned into a series of meeting rooms and glass screens used to separate the main worship space from the body of the church.”

- Congregational member of Trinity church:

- “Because St. Margaret’s has such large spaces, microphones and amplification have to be used. We oppose the use of such ‘technology’ – it interferes with the word of God!”

- Organist of St. Margaret’s:

- “If you partition St. Margaret’s, you will be losing the finest acoustic in the county. I don’t know the actual revenue figures, but a number of chamber orchestras and other instrumental groups use the building on a regular basis to make recordings for CD and radio broadcasts. They also hire the organ and piano, both of which are outstanding instruments. These fees help maintain them and the building.”

- Accountant to St. Margaret’s:

- “I’m surprised to hear that St. Margaret’s is financially unhealthy. Although our congregation is dwindling, our receipts from bequests are actually increasing and, as the building is in superb condition, I don’t anticipate any capital expenditures for years to come.”

- Congregational member of St. Margaret’s:

- “Of course the congregation of St. Margaret’s would welcome the congregation of Trinity church if they chose to join us.”

- Congregational member of Trinity church:

- “Thank you for your welcome, but we would need to be sure that we could have our normal service, led in our own way at 9.30 a.m.”

- Congregational member of St. Margaret’s:

- “Well I’m not sure that’s possible as our service starts at 10 a.m., so your service would have to start at 9 a.m. or 11.30 a.m.”

- Congregational member of Trinity church:

- “Why should we have to adjust our service times? We are the ones who would be sacrificing our building to move to your building. We also have many very elderly members in our congregation and getting to church for 9 a.m. on a wet winter’s day would not be possible. Why can’t St. Margaret’s move its services?”

- Vicar of St. Barnabas’s:

- “Before we get into the detail of changing St. Margaret’s, maybe we should think about St. Margaret’s congregation moving to Trinity church. Rebuilding Trinity with a modern design in a prime location is bound to attract attention and visitors. Now that businesses can open on Sundays, the church has to face competition for its services. St. Margaret’s is really too far from the centre of town. A new Trinity church would be an excellent visible statement of the progressiveness of the church. To fund this new building, I suggest that St. Margaret’s be sold off for development, as it is a large area of land in a very desirable residential area, where there is a shortage of parking space.”

At this point, an elderly lady struggled to her feet, her outstretched arm shaking with rage.

- Elderly lady:

- “Do you mean to tell me that St. Margaret’s would be turned into a parking lot – how dare you even suggest such a thing?! My husband is buried in those memorial gardens, as are the loved ones of many people in this meeting. How can you even think of building over them?!”

- Congregational member of St. Margaret’s:

- “I agree – how can you consider demolishing St. Margaret’s? I have worshiped there all of my life – for 60 years. I was married there and my children christened there. You cannot destroy St. Margaret’s. Anyway, who are you to say what should happen to St. Margaret’s? What has your congregation got to do with it? You don’t worship there – you don’t care!

”Later that evening, the new vicar of St. Margaret’s reflected on the situation and despaired. She had had no idea of the difficulties that “working together” would entail. There was even a question mark over her future already. Why would there be a need for two vicars in the same church? She was the most recent arrival and the other two vicars seemed to be against her. The telephone rang: - Congregational member of St. Margaret’s:

- “Sorry I couldn’t be at the meeting this afternoon, vicar. I gather it didn’t go very well – I bet the other two churches ganged up on us? Anyway, I have great news. In anticipation of those problems, I have applied to have our church listed as a building of important architectural interest – so it may be protected after all from change …”

The caller continued, but all the vicar could think about was tomorrow morning’s meeting with the bishop and his parting words from the last meeting:

- Bishop:

- “We really have to move things on, you know. Your parish is in the vanguard of change – everyone will be looking to see how you have handled this highly desirable move towards our ecumenical goals. I really hope you can tell me what steps you are taking towards this aim and the progress you have made when we next meet. Don’t let me down.”

10-4 The Oakland A’s: Billy Beane’s Leading Ugly

Over the past decade, the Oakland Athletics have regularly outperformed the bigger, richer teams in the professional baseball. They did this with a team of misfits and mis-shapes, passed over by the scouts from the other clubs. How? The answer may be a rather unconventional leader of change: Billy Beane.

As a promising young player, Beane was a “five tool” guy. He ran fast, threw strong, fielded skilfully, hit well and he could hit with power. In the mind of the scouts who selected players for the major league clubs, he was the full package. The icing on the cake was that he looked great: tall, lean, square-jawed. The scouts had a term for this: Billy Beane had “the good face”. He joined the New York Mets straight from high school. The Mets considered him as a better prospect than Daryl Strawberry, who they signed in the same draft. And then Beane’s playing career slowly fell apart. After toiling away between various major league club rosters and their feeder teams for nearly 10 years, he ended up with the A’s.

He then walked a path seldom trod, from the field to the front office. And there Beane found the Oakland A’s GM, Sandy Alderson. He asked Alderson an unheard-of question: could he hand in his glove and become an advance scout, going out on the road ahead of the team to watch and report back on future opponents? Alderson liked Beane. Beane treated him with a respect that baseball people often didn’t afford somebody who hadn’t played pro ball. Plus, Alderson admitted, “I didn’t think there was much risk in [it] because I didn’t think an advance scout did anything.” By 1998 Beane was in Alderson’s job.

Beane drew lessons from his own travails and his unique collection of perspectives. He was the first major league GM to have been a future all-star, a failed player, an advance scout and intensely curious about things outside of baseball. This enabled him to suss that certain types of players and skills were overvalued in baseball. Others, on the other hand, were not valued highly enough.

Beane failed as a player because he didn’t have it in the head. He was so good as a young man that he’d never really failed at anything. Subsequently, he crumbled under the pressure of the big leagues. He seemed unable to make minor adjustments that might have helped him, and became, in turns, paralysed by over-analysis and engaged in making wholesale changes that confused himself and his coaches until his self-confidence was sapped.

Such an embedded deficit was not apparent to a scout watching a high school star. As a player, “I was sort of misjudged,” Beane would later explain. “[T]hey were measuring the wrong things, like running speed and strength, and they were undervaluing guys who actually did things (such as get on base and score runs) that contributed to winning games … There were a lot of guys who maybe weren’t the natural athlete I was, but they were much better [pro] baseball players.”

Beane’s emerging views about what was over- and undervalued in baseball, and his elevation within the A’s front office, emerged at a fortunate time. Former A’s team owner Walter A. Haas Jr. was prepared to sink his own fortune into keeping up with the big club’s spending. New owners Stephen Schott and Ken Hofmann weren’t. As a business proposition, pumping millions into a team that relatively few people supported (the population of Oakland is just over 400,000) made no sense to them. Scott and Hofmann made innovation a matter of urgency. Beane was the right leader in the right place at the right time to revolutionise the A’s strategy, and, subsequently the way professional baseball teams are led.

Together, the new owners and Beane worked out a new approach, and what seemed a source of perennial shame became a rallying call for the underdogs: “We can’t do the same things the Yankees do,” Beane said. “Given the economics, we’ll lose.” Unable to join them, or follow what was best practice for the big clubs, Beane set about seeing if they could beat them at a different game: trading.

He would assemble a team that would sign the players nobody else wanted – “fat guys who don’t make outs”. After buying low, Beane would look to sell high as his players became established and successful, by which time he would have another “ugly” and cheap cohort rising through the ranks. This was the strategy, but achieving it would require promoting a number of things that baseball insiders currently didn’t value, and, subsequently, demoting a number of others that had long gone unquestioned.

Beane’s former boss Alderson had introduced him to Bill James, a little-known amateur publisher of pamphlets of statistics that most baseball insiders considered unimportant. Beane saw in these numbers an ability to map something that he had been gradually sussing for some time. James provided proof that what mattered most in terms of winning baseball matches were the ugly things: primarily scrambling to first base by whatever means, particularly through walks. Consequently, the stats that most people in baseball did focus on, like batting average (which does not include walks), were the wrong ones.

Alderson could see this and the consequent arbitrage possibilities it might afford, but found it hard to push the envelope without a baseball pedigree and under Haas’s free-spending ownership. The stars aligned far more favourably for Beane to build upon his mentor’s insight and put James’s numbers into practice.

But there was still a battle to be fought against the old baseball thinking. Whereas the kingpin at a baseball club was generally the first team manager or coach, the A’s new owners supported Beane’s installation of a different kind of man in this role. Coach Art Howe was put in place to follow Beane’s strategy. This team would be led from the front office, not from the dugout.

Beane then set about dismantling the monopoly that the scouting team had on recruitment. The secret weapon in Beane’s armoury was Paul Podesta, a Harvard graduate with a laptop. Beane subtly promoted Podesta, a statistician with no track record in the game, into the mix when prospective new players were being evaluated and when the front office was deciding who to buy ahead of the draft.

These discussions had as their focal point a big whiteboard with the names of players to be ranked in order of desirability. Beane would begin by listening to the scouts outline their top picks. Then he would use Paul’s stats to critique their ideas.