12

The Maverick: Six Senses of Strategy

What does an organisation’s building say about its strategy? Does it matter if it is enclosed in a quirky historic building or located in a tower block? Modern art on the wall or old masters? Hushed tones or loud “muzak”? Leather Chesterfields or Ikea? A musty old book smell or refreshing Jasmine? What does a CEO say about an organisation’s strategy? Does it matter if …

John Harvey-Jones

In each edition of The Strategy Pathfinder we have tried to do something a little different in the final section. In the first two editions, we used this “Maverick” section to outline new horizons in strategy and other related fields. In this edition, we encompass many such new developments in a new way of sensing strategy, something we call “Sensography”1 and a related framework for categorising and evaluating these observations, the Six Senses of Strategy Wheel. We outline these concepts and frameworks and the thinking behind them in the paragraphs and images that follow.

Our Six Senses of Strategy framework, and the sensographic approach that underpins it, is based on our many decades of advising organisations, assessing their strategies and helping with suggesting options. Approaching their buildings for the first time, we have often sensed their strategies before meeting anyone at all – the clues lie all around. Rather like detectives trying to piece together what we are looking at, we realise that the choice of buildings, their location, the pictures on the walls, the behaviour of staff acting out their daily routines, the sounds of activity (or lack of it), the textures of furniture and documents and the tastes of refreshments are not accidental. Everything has been the result of conditioned choice, even if unconscious. Deep-seated views about what the organisation is about, its purpose, is its strategy in action.

We are not the first to suggest this connection. In the 1980s, John Harvey-Jones (regarded by many as the original “management maverick”) used a similar approach to assess the “real” strategy of an organisation rather than what they espoused in their vision statement or glossy strategic planning documents.2 And the similarly iconoclastic academic Karl Weick argued that an organisation’s strategy and corporate culture are one and the same.3 Recalling his work makes recent arguments about whether “culture is more important than strategy” redundant. They are the two sides of the same coin (as we explored in Chapter 5, Resource-Based Advantage).

However, we have developed a framework to assess by other means (i.e. not the normal tools, frameworks or technical measures so far described in this book) the implicit strategy of an organisation. We have termed the thinking behind it “Sensography”4 and it was inspired by a visit to the museum of medieval history in Paris, the Musée National du Moyen Age.

The Musée contains a famous medieval tapestry series, The Lady and The Unicorn, which consists of six tapestries with the Lady surrounded by various people, objects and animals, and engaged in different activities. It is clear that the first five tapestries depict the five senses: sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. But a medieval mystery lies in what the sixth tapestry, or the sixth sense, might be?

In order to get to the “Sixth Sense of Strategy”, we used the tapestries as a guide to what is lacking in our current understanding of strategy, drawing on examples from the business world, but also the latest thinking in a wide range of fields: from education theory to optics to physics to food science and psychology.

What we found was that the field of strategy has only begun to scratch the surface of what is emerging in these other fields. Almost all of our understanding of strategy and how we represent it is visual, and even here we only use or appeal to this sense in an extremely limited way.

In the following sections, we show how each sense can inform an observer about an organisation’s strategy. When we arrive at the sixth sense, we suggest various possible answers to what this could be. We conclude that the power of the sixth is that it detects coherence between, and essence within, all the other senses, an element that we might describe as the “heart” of an organisation that makes the sum of the senses greater than the sum of its parts. This thinking helps us to detect when a strategy just doesn’t seem right, provides clues as to how it could be fixed and supports one answer to that medieval mystery.

VISUAL Observations of Strategy

In the Sighttapestry at the Musée National du Moyen Age, the Lady is seated, holding a mirror up in her right hand. The unicorn kneels with his front legs in the Lady’s lap, from which he also gazes at his reflection.

Generally, the first sense to encounter a product or a service is sight: we see it; and when an organisation develops a strategy it is generally communicated in visual form as a strategic plan mostly composed of text and numbers. But this is a very limited use of sight to get a sense of an organisation’s strategy. A number of other visual “cues” that you could look for in your sensographic observations include:

- The Buildings in which organisations are housed, particularly their “head-office” appearance and locations. Are they ostentatious or discrete? Their external appearance – are the buildings stainless steel and glass or historic brick and timber? Their internal configurations – how is space used5 (open plan v. closed, hot-desking). Are walls opaque or transparent, to see colleagues?

- The Design elements in an organisation (e.g. how would you describe the design style present in your organisation and its surroundings)? What does the furniture look like (leather chairs or timber; designer furniture or standard)? What does the lighting look like? Is it subdued, glaring, spot lit, soothing?

- The Artwork sponsored by the organisation: the paintings on the wall (are they modern, abstract, indigenous, international, or historic and classical, or a mixture?); the images used on the website and other documentation; the font and design of the corporate logo.

- Visual Advertising. Check out and assess the history of the organisation’s marketing campaigns; their social media accounts like Twitter – what is being featured on these and at what frequency, who are their followers?

All of the above constitute elements of the environment(s) which influence those working in them. These “affordances” not only constrain and allow certain ways of behaving, but also give clues to the observer as to what may be actually happening, or not happening, in a particular organisation.The CEO and top management are the “lightning rod” for stakeholders and attract a lot of attention. Their appearance is telling you something:

- The Appearance of CEOs and other senior managers. How do they look? How do they present themselves – a suit or jeans, tie or open shirt, casual shoes or brogues? Rolex watch or Fitbit? Jewellery or not?

- Management office/s, their size and configuration, their company car/s; the style of their portraits on the walls or on the web; do they walk the floor, interact with customers, spend the majority of their time in their office?

One can also learn a lot from observing employees’ appearance

- The Uniform or dress code of employees. Is it casual or formal, stipulated by the organisation or down to individual choice? What does this say about order and control, employee autonomy?

AUDIO Observations of Strategy

In this, the Hearing tapestry, the Lady plays a musical organ perched on top of a table while her maidservant stands on the other side of the table and operates the instrument’s bellows. The lion and unicorn frame the performance holding up the pennants. “What sound does a strategy make?” seems like an odd question. It is a far less obvious than “What does a strategy look like?” but is a no less real illustration of whether a strategy is working or not.

Think of Singapore’s Changi Airport. It is the world’s most awarded airport, by a considerable distance. If you’ve been there, try and recall how it sounded. A great airport requires more than just being clean and efficient and a lot of thought goes into not only how Changi looks and feels and smells, but also how it sounds. It sounds active and busy, but not frenetic or cold and abrupt – which is quite a feat given that 70 million people pass through Changi every year (www.changiairport .com).

While Changi’s is great sounding strategy, there are also examples of transport hubs where the sound of strategy is not working. Many airports and railway stations are noisy and sonically confused. How often are announcements made where they cannot be heard, are indistinct or drowned out by other sounds? What strategic message is this cacophony conveying? What emotions are being provoked among its customers and other stakeholders?

While transport hubs in general are an interesting example that many readers will relate to, the same principles apply to a bookstore, a branch of a bank, a car dealership, the sound a chocolate bar wrapper makes when it is opened or the sound of a car door closing. Indeed, a recent advertisement for one make of car focused upon other manufacturers’ cars and how they all aspired to sound the same as their solid, reassuring “chunk” – but without success.

Here’s a short list of auditory cues that you might want to consider:

- Oratory. Who speaks for the organisation (in the media and elsewhere) and how would you characterise the style of this oratory? Is there a standard national or professional “accent” favoured?

- How does the CEO sound? Does he/she have a reassuring tone of voice, which might be a deeper pitch in Western cultures, for instance. In the UK the first woman prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, taught herself to speak at a lower pitch to give her messages more gravitas. She also spoke more slowly, at a more measured pace, as she became more powerful, to indicate weight of message and thoughtfulness. Those speakers who rush seem to be uncertain in their messages and generally don’t inspire confidence, especially if words cannot be heard distinctly. For this reason, many world leaders repeat key words for emphasis, to ensure listeners hear the key points and to reinforce the message. Interestingly enough, in the recent Brexit debate in the UK, a figure of £24bn of savings suddenly emerged and was repeatedly endlessly despite having no foundation in fact, but it became “a fact” and was persuasive.

- Stories. What are the official stories told to convey the sensibilities of the organisation, and the unofficial stories told to convey to newcomers “how things really work around here”? So often one can get greater insight into the nature of an organisation from casual stories told at coffee breaks or socially than from the official line (if you can get access to those).

- Slogans. Advertising slogans of those sayings that permeate the organisation. What are they? How does the repetition and the memory of them provide strategic resonance and renewal?

- The bustle (or lack thereof). How does the workplace sound? What is the entrance hall like? What about the production line or the warehouse? Is there an energetic buzz? A professional silence? A mad cacophony? A mechanical whirr? An echoing space?

- Product and service sounds. Korean cars have been able to close the (perceived) quality gap in the auto industry, in part, by making their cars sound “more solid”. Harley-Davidson have attempted to patent the sound of their engines. Mazda engineered the sound of their MX5’s exhaust pipes to mimic UK sports cars. Retailers and hotels often play music throughout their buildings, including elevators and washrooms, but are their choices always the right ones (see the Exercise case at the end of the section)? Serious research has been conducted into the playing of classical music at railway stations to deter thugs from hanging around and to calm travellers. Nike knows that making a “swoosh” sound has an uplifting effect on a customer. And Apple Mac users love the sound their computers make when starting up. All this suggests that sound is a vital component of any product, service or experience.

So, having observed these things, do you think the organisation that you are investigating, and their products and services, emit sounds consistent with the sort of strategy they are seeking to convey or deliver? If not, or if you are not sure, then something is out of kilter.

TASTE Observations of Strategy

In the Taste tapestry, the Lady is taking sweets from a dish held by a maidservant. Her eyes are on a parakeet on her upheld left hand and the monkey is at her feet, eating one of the sweets.

Again, this does not seem like an obvious line of inquiry in assessing an organisation’s strategy, but many of the world’s grand old organisations have recognised for centuries the symbolism and effect that food and drink, and gatherings around either or both, can have.

While working with merchant banks in the City of London in the 1990s, it was still obvious that the various banks would convey their character and style through their meals. English merchant bank Hambros offering the traditional English roast beef dinner, while French investment bank Paribas’s association with the Roux Brothers, regarded by many as the godfathers of modern restaurant cuisine, certainly helped lure new clients to the bank and probably helped close a number of difficult deals.

Natural History New Zealand CEO Michael Stedman seeks to position the world’s second-largest producer of nature films against the biggest: the BBC. “At every opportunity when we are building relationships with new employees, new distributors or at trade shows,” he explains, “we roll out New Zealand wine and food. It helps us to portray the Company as young and zesty.”

While one of the most interesting experiences in watching a television series like Mad Men, based on an advertising agency in the 1960s, was the quaint other-worldliness of the whole office closing for an hour to go for lunch (and to network and do deals), our understanding that food and drink can excite and influence certain types of response and behaviour may be now undergoing something of a renaissance. TV executives and the book industry know that food TV and cookery books are the fastest growing segments in their industries. From the positioning of coffee facilities to the positioning of particular kinds of chocolates on hotel pillows. From Google making food available to the new hires it gathers from around the world to help them bond with their new colleagues, to other organisations sponsoring international “bring a plate” food events to enable employees to show off their native cuisines … Just as we have known for some time that an army marches to a particular beat according to its stomach, we increasingly understand that civilian organisations do too.

Some taste observations that a good strategy “detective” should explore include:

- Styles. What kinds of food and drink are provided for employees (is it subsidised, is it served on the premises etc.); and what food and drink-related events do the employees organise for themselves? Is it tasty? Is it sweet and/or salty? Is it distinctive?

- Ceremonies. Any food and drink traditions? A particular type of tea service, sweets, port after dinner, coffee mornings etc.

- Hosting. How does the organisation “host” its guests?

- And, finally, to take taste more figuratively, what does the organisation’s culture promote as being in good or poor taste?

OLFACTORY Observations of Strategy

In the fourth tapestry in the Musée in Paris, the Lady stands, making a wreath of flowers while her maidservant passes flowers to her as she works. The monkey has taken a flower, which he is smelling.

For most readers, the oddest sense in this list to seek to apply to strategy will seem to be smell: smelling strategy sounds somewhat ridiculous, but advances in a number of different fields of science show that smell really matters, affecting our perceptions:

- Anatomical studies show that the average human being can recognise up to 10,000 different odours and scientists have begun to recognise smell as likely the most evocative, associative and nostalgia-inducing of our senses.

- Recent results from tests in Japan show that people’s ability to do mental arithmetic can be positively and negatively affected by different smells. Aromatherapy is now being used in many companies in order to improve employees’ sense of well-being, as well as their productivity.

- Leading hotel chains increasingly utilise smell to emit the essence of their “brands”. For instance, studies have shown that the boutique hotel Naumi’s pumping of a lime green scent throughout the hotel was successful in differentiating it from the competition in the minds of its customers.

- In some US shopping malls baby talcum power is pumped through the air conditioning system as it is now recognised that older shoppers purchase more when remembering infancy.

- Coffee chains such as Starbucks and Costa put a lot of thought into how they project the smell of their offerings; and booksellers carefully consider the placement of their cafés to lure in shoppers.

- The California Milk Processor Board attached cookie-scented strips to its advertisement in bus shelters for milk (while these were removed by City Councils because of fear they may be asthma inducing, the ensuing media coverage and debate did result in increased sales).

- Recognising that the one thing that makes Crayola crayons unique was the smell that connected buyers to their childhoods, the company set about deconstructing the ingredients in the crayons that gave them their distinct smell in order to patent it.

- In the United Kingdom, rival cat-food brands struggled for years to figure out why Whiskas would almost always win “taste-tests”. Years of attempting to reverse engineer the relative amounts of ingredients in order to recreate the taste were to no avail. The secret to why cats would go to a bowl of Whiskas over other brands turned out to be the perfume – and this is incredibly hard to imitate.

But really these examples are only proving and adding to a depth of understanding about what we have likely always known. It is common knowledge that the smell of baking bread or coffee helps sell houses. And as Marcel Proust put it in The Remembrance of Things Past: “When nothing else subsists from the past, after the people are dead, after the things are scattered … the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls … bearing resiliently, on tiny and almost impalpable drops of their essence, the immense edifice of memory.”

And adding to the value of the olfactory aspects of an organisation’s activities is their inimitability. Unlike sounds, sights and the way things feel, smells cannot be copied and they cannot (yet) be reproduced digitally.

However, the converse is also true – smell can also undermine strategy. While we are hypersensitive to bad smells when this relates to food products, we also react negatively even when smell might appear peripheral to the offering. We can make a lasting judgement about a firm’s strategy through our impression of smell, particularly when we are looking for proxies of services or products that cannot easily be evaluated. For instance, in choosing a nursery for a child, we try to focus upon the personal care they will receive during the day, but are also likely to be influenced by whether the premises smell musty. In buying your first musical instrument from a shop you may be influenced as much by the smell of the place (and in some cases the vendor) as the musical capability and price of the instrument itself. In one recent case, a well-known coffee chain changed their floor-cleaning liquid in order to save costs. The strong smell, however, compromised the more delicate coffee aromas central to the company’s strategy and there was a noticeable dip in sales as a result.

The examples provided above only deal with the most obvious applications of smell, and thus only scratch the surface of how smell can be used to more effectively communicate strategy. Further interesting applications include questions such as what should a branch of a bank smell like, or an airport, or a management consultancy? What does efficiency smell like? What does differentiation smell like? And, as technology advances, and websites, annual reports and PowerPoint presentations are able to use scent, the application of scent to strategy will become of increasing interest and concern.

And so, to the growing list of sensory observations that a good strategy “detective” should explore, we can add:

- What does the smell of the organisation’s buildings, products, offices, dealerships and other sites convey about its strategy?

- What about the CEO and the management team – are their scents reassuring or worrying? Is this the smell of success or fear?

KINETIC Observations of Strategy

In the fifth or Touch tapestry, the Lady stands with one hand touching the unicorn’s horn, and the other holding up the pennant.

Imagine this scenario: you have just received an envelope from a company you own shares in. It is one of those envelopes that contain annual reports explaining what your company has done over the past year and what it plans to do now. You open it and inside are rough pages of cheap foolscap paper. Even before you start to read the description of the company’s strategy your confidence is impacted. It’s not just that this strategy doesn’t look right. It doesn’t feel right.

On the other hand, a couple of years ago we received a strategy document from a Japanese company with text embossed on the finest rice paper – a perfect medium to express the company’s strategic identity. It may be no coincidence that the Japanese have made an art of gift-wrapping and see the wrap as integral to what lies within. The Japanese seem to have an unnaturally good feel for this, but not exclusively. Apple has made a science of figuring out the optimal feel for how long it takes for the bottom of an iPhone box to gently drop as you hold up the top part of the box (seven seconds: the golden mean before heightened anticipation tips over into frustration).

The feel of an annual report; the welcome (a handshake, a pat on the back, a kiss on the cheek, nothing?); the seats in the lobby; the business cards; the feel of the boardroom table (what kind of wood is it?); the temperature the rooms are kept at; these are all telling kinetic points of contact with an organisation’s strategy. Not to mention the “feel” of the organisation’s products or the warmth of the service.

While it is easy to talk the talk, or write the words of a strategy, walking the walk, as it were, requires close attention to these touch-points: a good strategy should have a feel consistent with what it is trying to convey and trying to achieve.

Hence the new academic interest in studying the practice of strategy and what is referred to as “social materiality” relating to the physical aspects of the organisational environment and how these can affect the way practitioners think and act. For example, studies are starting to show that one of the main benefits of organisations taking “strategy away-days”, physically relocating staff to surroundings where the furniture and feel of the place are completely different from the normal workplace, is that people become less constrained by day-to-day routines and are able to broaden their thinking. This separation from everyday life enables greater focus on strategy issues without distraction and the surfacing of issues that could not be articulated before.

Moreover, the feel of a product is a particularly important vehicle for conveying the strategy behind it. Wine and beer-makers know that the bottle may be more important than what is inside when it comes to buyer behaviour in crowded markets where it can be difficult for many to discern differences in taste. Think about why so many people claim to like Grolsch beer. To what extent is it that it tastes different from other European lagers; and to what extent is it the prospect of popping the cap on its distinctive bottle? Indeed, there is growing evidence to suggest that the feel of a vessel can influence the way our other senses respond to the product or service within.

The most ubiquitous example of this phenomenon is Coca-Cola’s iconic contour bottle, created by Earl Dean. In 1915, Coca-Cola launched a competition to create a new bottle. The brief: “a bottle which a person could recognise even if they felt it in the dark, and so shaped that, even if broken, a person could tell at a glance what it was”. Dean’s team decided to base the design on one of Coke’s main ingredients, either the coca leaf or the kola nut. While researching these forms, Dean was inspired by a picture of the gourd-shaped cocoa pod in the Encyclopedia Britannica, and made a rough sketch of the pod. This became the basis of the prototype, which evolved into perhaps the best recognised vessel on the planet. One that many people believe makes the contents taste better.

More generally, as employees and consumers are increasingly attempting to evaluate things such as truth, honesty, quality in products, services and experiences, they sense-out tangible clues and cues, such as weight of fabric, smoothness of surface or thickness of paper, as indicators. Particularly where the offering is an intangible, such as financial advice, or education, customers unconsciously seek proxies for the quality they want, and assurance about its durability over time. Are you being given coffee in a cardboard cup or in a bone china cup? Are you signing a document with a disposable biro or a fountain pen? Is the CEO’s handshake firm and reassuring or limp? Feel is a very powerful way to make such strategic intangibles tangible and the keen strategy investigator can see this by carefully observing:

- The Feel of the organisation’s products and artifacts

- The Warmth (or other feeling) created by the service

- The nature of the Touch-points when one encounters the organisation

- The Material surroundings when you enter the organisation’s offices or outlets.

The “SIXTH SENSE” of Strategy? The Keystone

The sixth tapestry, A Mon Seul Désir, is different in style. We “zoom” out for a wider perspective. There is a tent behind the Lady, across the top of which is written A Mon Seul Désir. This is an obscure motto, variously interpretable as “my one/sole desire”, “according to my desire alone”; “by my will alone”, “love desires only beauty of soul”, “a calm centre within the passion”. The Lady is placing the necklace she wears in the other tapestries into a chest held by her servant. This is the only tapestry in which she smiles, serenely.

What this tapestry means remains uncertain. It appears to refer to a sixth sense. But what this would be has provoked intense debate through the centuries.

One interpretation suggests that the French words, “à mon seul désir,” translate to “with my unique desire”, meaning that humans are the only species that covet material objects even as we share the five senses with animals. One interpretation sees the Lady putting the necklace into the chest as a renunciation of the passions aroused by the other senses, and as an assertion of her free will. Others see the tapestry as representing love or virginity.

Another line of thought sees the tapestry as representing a sixth sense of understanding (derived from the sermons of Jean Gerson of the University of Paris, c. 1420). And it is the combination of all the senses to develop deeper understanding that separates humans from animals. Hence the deeper layers provided by these essential understandings being placed in the chest and then into the blue tent. Building on this interpretation, the interpretations that still retain the most support build on this notion of the sixth sense being a deeper understanding drawn from all of the senses used in concert.

Some variations on this theme include that:

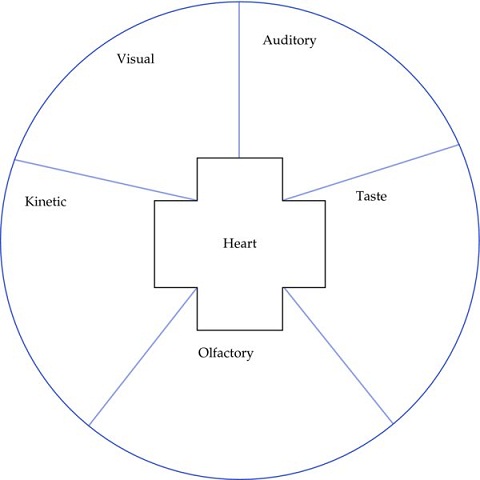

- The sixth sense is the internal organ of the heart, in which resides love or emotional engagement.

- That the sixth sense is an internal process of intuition that comes from being well-attuned to what the senses, as an integrated whole, mean.

- That the sixth sense is about internalising, bringing together and combining the five senses. The sixth sense is coherence.

We conclude the sixth sense of strategy, the sensographic heart of strategy in other words, to be the essence that joins or integrates the other senses, brings them together and helps them all turn in the same direction. The expression of this keystone provides a coherent purpose.

The key sensographic observation of any strategy should therefore be: do the five sensory manifestations of our strategy fit with, reinforce and heighten one another? Is the whole greater than the sum of its sensory parts? What is at the heart, at the centre of things, and how might we express that heart?

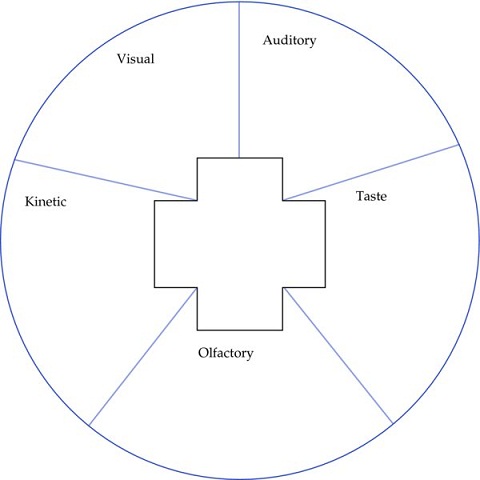

Having outlined what we have come to regard as the six senses of strategy, the senses that we, for many years, used intuitively when analysing organisations’ strategy, we have organised them into the visual framework which we term The Six Senses of Strategy Wheel (see Figure 12.1). In the next and final section of this Maverick chapter, titled Sensography in Action, we provide opportunities to apply the framework to analyse the strategy of a number of organisations in a unique sensographic way.

Figure 12.1 The Six Senses of Strategy Wheel

But before we get there, it is good to reflect that in a way we have circled back to our very first chapter on Strategic Purpose, and strategy being about winning by working to achieve this sense of purpose. Being able to analyse an organisation using the Six Senses of Strategy Wheel can provide a very good understanding of the actual strategic purpose it is projecting, or failing to project, and help answer the questions we posed of organisations in that chapter.

In our experience of using the Wheel it has become clear to us that John Harvey-Jones, with whom we began this chapter, was right: successful organisations are the ones where strategy emanates from the heart, the other sensory aspects flow from and reinforce this and are advanced naturally by the people who work there. As he put it: “How do you know you have won [as a manager or a strategy advisor]? When the energy is coming the other way and when your people are visibly growing individually and as a group.”

Maverick Strategies Key Learnings Mind-Map

Having read and reviewed this chapter, outline what you believe to be the key learnings from the chapter and the relationships between these on the note pages below.

Apple: Sensography in Action

Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?

Steve Jobs

The success story of Apple after the return of Steve Jobs is well known and the subject of several Hollywood films. In terms of consumer products, first the iMac was released which was then followed by the iPod. Then the MacBook hit the market to be followed by the phenomenally successful iPhone. This was followed by the iPad and latterly the Apple Watch. Often highly visible in premium high street locations, as the light pours through the large glass windows, customers love going into white and bright Apple stores to try out the latest minimalistic, sleek, brushed aluminium MacBook Pro or rounded edged Apple Watch. The stores always seem full and yet generally the only sounds are those of the occasional device powering up with a distinctive start-up chime, or an infrequent “clunk” or a blip, if an error has been made, although the devices are so intuitive this is unlikely – and the helpful assistants, and even other customers, will help solve problems, such is their enthusiasm for the products. To keep customer interest high, Apple has followed every step change in innovation with a rapid series of further refinements, such as nanos, touch, air, classic, pro and mini. These successes help explain why in 2015 Apple made the biggest corporate profit in history with $53.4bn. As Apple’s vision statement says:

Apple is committed to bringing the best personal computing experience to students, educators, creative professionals and consumers around the world through its innovative hardware, software and Internet offerings.

Customers lucky enough to purchase an Apple will pick up a beautifully packaged item in a robust white box simply marked with a discrete Apple logo, or a transparent container showing the item on display inside. Opening the box later, it is truly impressive the care with which the product will have been packed, nestling in a deep, white shock-absorbing material, with every component neatly contained in a sterile envelope; not at all what one might expect for a piece of electronic equipment. And the instruction book is also white with the Apple logo on the front. Once up and running the device can communicate easily with other Apple devices and share services such as the huge music and video library, iTunes. When people use an Apple product, despite its understated appearance, no one would really confuse it with another brand.

Since Jobs’ death, Apple’s performance has been rather varied. Although there remains enormous excitement at the launch of each new product, this has not always been reflected in the stock price. This has been attributed to its difficulties in coming up with really innovative products. Many believe that all Apple is doing is rolling out incremental changes to existing ones; smaller, thinner, faster, etc. This matters, as capable competitors, such as Alphabet, Samsung, Huawei, Sony and HTC are hot on Apple’s heels, showing they can also produce smartphones, tablets and mobile computers among other things.

BIPA: More than skin deep?

BIPA GmbH is the third leading beauty, personal care and household retailer in Austria.6 The company has a comparatively wide-range focus, and has traditionally been predominantly involved in cheap perfumery wholesaling activities since its conception in 1981. Before 2009, its business model revolved around low-cost household and personal care items with a great emphasis on its mid-mass market health and beauty offerings. However, between 2010 and 2013, BIPA faced a difficult retail trading environment, characterised by restrained consumer expenditure and intensifying competitive pressures. In addition, market growth was partly driven by commodities such as toiletries and skin care and not so much in fragrances and make-up, in which BIPA had heavily focused their efforts. Although BIPA managed to increase total retail sales by 7.2% in 2013, profit decreased −23% (DerStandard, 2013).

In response to changing market conditions, BIPA decided to reposition by focusing on a differentiated premium business-level strategy, in an attempt to increase revenues and profits. The plan involved converting its stores into premium trendy franchises, in line with its strategic move away from being a classic low-cost retailer. This involved new thinking about the nature of BIPA stores.

The old concept stores had been between 500 and 1200m2 and were located in urban centres, near supermarkets where there was large footfall. The aim was for these stores to be practical and convenient for customers who would notice that they were clean, friendly, tidy and odourless. The company logo was prominently displayed in thick pink letter blocks that might appeal to the older generation remembering their childhood or thinking of grandchildren. These colours are often associated in Austria with bargain basement prices and this appeals to lower-income working consumers and students. Upon entering any BIPA store, new or old, customers hear in-store live broadcasts from Radio Max. The cool sounds of Pink, The Space Brothers and Enigma grab you as you walk by, providing an energetic, youthful, vibrant, proactive and inspiring environment. The geometric lines of the counters allow for efficient access from the front of the store, where more impulsive purchase items are located on brightly lit shelves, to the “written on a shopping list” items, located on low, lit shelves, at the back. Often there are so many products that there can be a rather cluttered appearance, and in certain sections there is some localised collision of odours, although not throughout the store as a whole. There are frequent labels announcing multi-buy deals and special offers. These stores are self-service, and customers can also try products out for themselves. There are normally one or two members of staff available on the floor to help customers with more general enquiries, but often customers do not stay very long in the stores, leaving once they have located the items at the price they need.

The new premium stores are less than 800m2 in size and located in more exclusive districts, away from main traffic routes and the airport. The emphasis is on glamour, affordable exclusivity and coolness and aimed at young females in particular. The company logo is still in evidence in thin white and pink letters. Entering these premises, customers are greeted with round counters and wide aisles. In the centre are beauty counters with stools to seat customers for make-up application and consultations with trained staff dressed in white lab coats. Consumers are also allowed to smell the various products and the beauty consultants help suggest and customise the product mix according to their needs, allowing them to try various textures on their skin ranging from powder to cream and mousse. It can take some time for consumers to finally make a choice of product. There are even innovative products that include fruitful lipsticks with strawberry or other flavours and creams that smell of chocolate. Focus is very much on cosmetics and perfumes, with high-end, luxury foreign brands available on discretely back-lit shelves, with black, white and pink colours (a dark glamour effect). Mini beauty parlours and aesthetics “salons” are there for customer use and the store overall provides a luxurious and welcoming environment. With signature fragrances in the air, the consumer is made to feel relaxed and comfortable. Touch screen multimedia screens are available to help with choices and numerous staff are on hand to help with any questions.

Despite the initiative to move into the premium business-level segment, lack of customer buy-in to the new stores has caused BIPA to scale back its ambitions, going back to its roots of a “Best Price Guarantee”. While there had been talk of having a large number of premium franchises across the country, any reference to a time frame was dropped.

Exercise Group

The fitness industry in the UK is big business. There are 6,500 health and fitness clubs in the UK, taking £4.4bn (2016) in revenue every year from 9 million customers (one in every seven of the UK’s population), and the market continues to grow as society becomes increasingly health conscious. It is also very competitive as health clubs fight for the attentions of potential customers. A common business model is one based upon the ability of clubs to continuously expand membership in order to fund subsequent opening of new buildings. While this has allowed many clubs to set up and grow quickly, this is often followed by failure or sale. The industry is still fragmented, but there are 15 large chains and a trend towards consolidation. Among the clubs there is a rapidly growing low-cost private segment accounting for 32% of private sector membership. Pure Gym is now the largest provider in the UK with over 150 clubs. It is a low-cost fitness club that just has gym facilities. Its fast growth is mainly through acquiring competitors.

The Exercise Group is one of the more expensive health clubs in the UK with individual fees of some £2,000 per year. Its brochures and websites display clubs with grand entrances; there are fountains outside and extensive external hard and grass tennis courts in the distance. Internal photos show a tempting serene pool of light blue water in a discretely tiled setting, with poolside models in white sauna towels reclining on white sun loungers. This tranquil scene is complemented by other images in the brochures of other exercise spaces in the clubs. Individual fit young athletic people in white leotards are shown in the wide-open spaces of dance studios, a pleasing contrast to the polished wooden strands of the exercise floor. The gyms are extensive with a wide range of gleaming equipment and trainers on hand to give individual fitness advice. The clubs also display health and beauty centres with small fountains of water running over Japanese-style sculptures and white clad members of staff on hand to direct members to wellness rooms.

Entering into one of these clubs, automatic doors open discretely as one passes into softly lit interiors, where, next to the reception desk, there is a shiny turnstile for admittance. Smart receptionists will sometimes welcome you as you slide your membership card through the turnstile card reader. Often this area gets a little crowded with members having forgotten their access cards or needing to request a towel for showering off later, as these can only be picked up from reception. Receptionists often say the towels are rather thin and small to be more environmentally friendly. If you have forgotten your card the receptionist will ask your name to find it on the system so you can be admitted to the club.

One club, fairly typical of the group’s other facilities, is located close to a city centre where traffic is a problem. Popular music plays in the background to relax you as you enter, perhaps on your journey to or from work, and once admitted you can choose to be active and swim in one of the two swimming pools (one indoors as featured in the brochure and one outside), head to an exercise class or work out in the large gym facility. Alternatively, or afterwards, one can go to the bar area for a coffee or snack and sit in the dozen or so comfortable chairs to watch the football on a widescreen television mounted over the sofa. It is also possible to order more substantial food from the menu at lunchtime. The food is often a reasonably high-quality offering in Asian, French and English styles. It is fairly pricey and also not always available. Some regular customers prefer to have a quiet conversation in an adult-only area further away from the television, with just the background music muffling other noises. There is a newspaper stand with the main national papers on offer, although by mid-morning these are normally in a state of disarray, with people having torn out bits of interest to them and papers having been stuffed back into the rack. The coffee grinder reminds people in the bar area that the coffee is good quality, although it does create some long queues from time to time. The seating area can get quite crowded and often the bar staff do not have time to collect everything from tables.

On the walls of the entrance area are a series of very detailed notices about the rules and regulations of the club so members can see that high standards are kept, and there is a prominent notice board which lists all the complaints of members in the previous month with colours denoting the extent to which these have been addressed. Some have green colours against the complaints, but most are currently being addressed. Also in the lobby area is a market stall of everyday materials and jewellery at bargain prices. Next to these is a glass case with pictures of property for sale in the area – most have price tags well in excess of £1m.

If one is aiming to exercise, then a thickly carpeted corridor leading from the lobby takes you towards the changing rooms. You will pass members kitted out in gym, tennis and squash kit as well as damp swimmers just in from the outside pool racing to get into the warm to dry off and change. Once inside the changing rooms there is a television often tuned to news channels, although this generally can’t be heard clearly over the soothing pop music. There are a large number of wooden lockers, although many are already in use, even though the club seems quite empty. Those that are available have a rather strange array of key fobs and it seems that some of the doors are slightly splintered, probably due to members losing keys. There are wooden benches to sit on which are rather worn. Many members bring flip flops if they intend to swim as the changing room floors tend to be rather wet and slippery from swimmers coming in from the indoor pool. As one might expect, there is a bit of a chlorine smell in the air. There used to be tissues readily available in the changing rooms, but these have now been removed as well as the bins in which to dispose of them. In the shower, there are two containers for shampoo and conditioner, although the latter is often empty. On the noticeboard, a comment from the management states that members often prefer to bring their own brands of conditioner to the club.

The 22-metre indoor pool has subdued lighting and consists of three lanes. One lane is generally taken up with numerous aqua aerobic classes, often for older and less able-bodied people, and the fast lane is intended for serious swimmers. When the aqua aerobic classes are taking place, the other two lanes of the pool have to be narrowed, which can cause a bit of congestion. There is a small pool for young children that can be used at certain times of the day. There is no lifeguard present at this facility.

There is an excellent set of four glass-sided squash courts which are quite popular with members. The lighting is good and the court condition high. There are also four indoor tennis courts with a good playing surface and adequate lighting. They are very popular with members, even though there is no heating in winter and the ventilation is very noisy and poor in the summer. For club night evenings and frequent tournaments, new tennis balls are always available. As the only indoor tennis facility in the area, it attracts those who want year-round tennis. This also means that there are often significant queues to get on court. From court one can clearly see the car park outside as the large security lights beckon through the windows.

The large gym has some of the latest exercise equipment, particularly in terms of weights machines. The running and cycling machines are in good condition and all are arranged in a curve so exercisers can see one another, and in the centre above them all are pre-programmed televisions which tend to run current affairs programmes with the sound switched off in case members wish to plug into the TVs in their exercise machines, where they have a large number of channels to choose from. Once watching a programme, exercisers are not distracted by exercise-related data. The temperature and humidity can be rather high in summer and for those in one half of the gym, scents and fragrances from the beauticians’ and hairdressers’ area next door can be smelt.

Recently, the Exercise Group has been experiencing financial difficulty and its membership numbers have been declining. Some have moved to other fitness centres and many have been attracted to the recently refurbished council-run facility with its high-quality gym, manned swimming pool, squash courts, games hall and annual fee of £400. In order to revitalise its membership, existing members have been promised a series of gifts if they introduce new members, such as bottles of wine, free guest passes and meal vouchers. In addition, they have been trying to attract new members with short-term membership offers rather than the current annual fee structure.

Writing your own “sensographic” case

Writing your own “sensographic” case

Refer to the section “Using Strategy Pathfinder for Assessments and Exams” at the end of the book (see p. 385). Under “the Mini Case” and “the Briefing Note”, guidance is given about how you can create your own case. You may already have an interest in organisations around you that you would like to understand in more depth – and a sensographic analysis is a good vehicle for that purpose.

In previous chapters, we have listed many websites and sources that can be used to gather information on organisations. However, distinctive to a sensographic analysis is gathering data that may well not be captured in conventional sources. This may mean that you will have to gather primary data yourself, through your own experiences, or find ways to uncover these data through other means – perhaps interviews, stories, film or pictures. You may find this a stimulating and new way to perceive an organisation, but also you may feel uneasy at trying to detect this “unconventional” data – after all we believe this approach does uncover “organisational blindspots” and often remains undetected by commentators. Nonetheless, we believe your efforts will be rewarded as you quickly gain penetrating insights into an organisation that may have eluded its stakeholders, although they may sense that an organisation lacks coherence for some reason?

![]()

Notes

- 1. Angwin, D. N. and Cummings, S. (2011) “Sensography”: Improving territorial coherence within organizations. Paper presented at the 31st Egos Colloquium, Gothenburg, Sweden.

- 2. You can see a number of Harvey Jones' documentary analyses of British companies on YouTube.

- 3. See Weick on ‘Strategy is Culture is Strategy', reproduced in the book Strategy Bites Back by Henry Mintzberg et al.

- 4. Angwin, D. N. and Cummings, S. (2011) “Sensography”: Improving territorial coherence within organizations. Paper presented at the 31st Egos Colloquium, Gothenburg, Sweden.

- 5. For more on the effect of space on organisational strategy, see Thomas, M., Angwin, D. N. and Dale, K. (2017) The effects of spatial configuration on opportunities for emergent strategy making, Academy of Management Conference, Atlanta, USA, winner of the 2017 AoM Strategy as Practice “Pushing Boundaries” award and Thomas, M., Sailer, K., Angwin, D. N. and Dale, K. (2017) The influence of spatial configuration on unconventional strategies, Strategic Management Society Conference, Houston, USA. For more on communicating strategy visually see Cummings, S. and Angwin, D. N. (2015) The Strategy Builder, John Wiley & Sons: 440.

- 6. With many thanks to Dr Ivona Brasnjevic, ICT – Innovation in clinical trials GmbH, Vienna, Austria, for help in preparing this case.