CHAPTER 2

The Rogue Trader

The Rogue Trader is possibly the most famous in the Pantheon of Rogues of Wall Street. Over the years, there have been two types of Rogue trader: the one who blows up the firm in a sudden frenzy of wild trading activity and the one who acts with slow, steady accumulation of risk, unbeknownst to firm's management.

Rochdale Securities, a once stable, small, firm in Connecticut, was taken out by a single trade in 2012 and so fits into the first category of a sudden burst of wild trading activity.1 Though the size of the loss was one of the smallest rogue trading episodes we have seen, $5 million in losses, its impact was devastating for Rochdale, which was subsequently forced to close. On the other hand, in 2011, UBS suffered far larger losses resulting from a Rogue Trader who slowly and steadily accumulated a huge level of risk, apparently unbeknownst to senior management. Like the Societe Generale episode before it,2 the Kweku Adeboli incident (see below) shook up the world of investment banks. “Could it happen here?” boards immediately wanted to know and they asked their chief executive officers. CEOs didn't know, so they, in turn, asked their chief risk officers. Their CROs didn't know so they asked their heads of operational risk. The heads didn't know so they asked their operational risk coverage officers. At that point, the question had probably already been answered in the negative back to the board so it probably didn't matter what the truth was. But the truth is, nobody knows where such an incident will happen again. The only thing that is known is that it will happen again somewhere.

Who Is the Rogue Trader?

So who exactly is the Rogue Trader, and what is the source of his roguishness? He is not the handsome rogue of your Victorian novel. Though he may be handsome, he probably won't want to attract undue attention to his activities. He is more likely to be the rat creeping around in your sewers, finding a home in the mess and dirt that never gets cleaned up. The profile of the Rogue Trader is fairly consistent: male, early thirties, not the most favored by birth or schooling. He likely has a strong sense of his abilities and is also likely to underestimate those of his better‐educated, more high‐born colleagues. More importantly, he is likely also to underestimate the risks of trading without active supervision. It certainly takes a good deal of self‐confidence to take on all the risks that the Rogue Trader takes on. Much of that self‐confidence is likely fueled by a bull market and a lack of experience and understanding of how markets can suddenly change to the negative. Like many traders, the Rogue Trader will tend to attribute his success to his brilliance rather than the market. Unlike other traders, however, he has no supervisors or colleagues to protect and help him when the market changes, because he does everything in secret.

Generally, the Rogue Trader is not a direct entrant into the bank's trading team but came to it via a role in operations or the back office. Nor does he generally work in the most prestigious or complex areas of trading. More likely, he is part of a team that facilitates fairly routine types of trades for institutional clients. In the stand‐out cases such as Societe Generale, Barings,3 and UBS, the Rogue Trader has been distinguished by his operational knowhow and his aggressive approach. However, such attributes do not necessarily set him obviously apart from his colleagues. Moreover, such aggressiveness is likely to bring plaudits rather than suspicion from his manager. Kweku Adoboli, for example, was reported to have participated in sports betting on the side, and was evidently warned against such activity by compliance. Such activity could potentially have been a red flag. However, for those who have read Liars Poker4 and read about the card‐playing exploits of investment bank executives like James Cayne,5 such activity did not obviously stand out on the trading floor. In fact, it may be that supervisors would have seen this as an indication of the type of aggressive trading activity they were looking for in their young traders.

Indeed, after working for two years as a trading analyst in the bank's back office, Adoboli was promoted to a Delta One trading desk. In 2008, he became a director on the ETF desk, and by 2010, he was promoted to director, with a total annual salary of almost £200,000 (about $254,000). Beginning in 2008, Adoboli started using the bank's money for unauthorized trades. He entered false information into UBS's computers to hide the risky trades he was making. He exceeded the bank's per‐employee daily trading limit of $100 million, and failed to hedge his trades against risk. In mid‐2011, UBS launched an internal investigation into Adoboli's trades. On September 14, 2011, Adoboli wrote an email to his manager admitting to booking false trades. His trades cost the bank $2 billion (£1.3 billion) and wiped off $4.5 billion (£2.7 billion) from its share price. The trading losses he incurred while trading for his bank were the largest unauthorized trading losses in British history.

In other respects, Kweku Adoboli fitted the classic Rogue Trader profile to a tee. Being from Nigeria, he was clearly not from the classic Oxbridge, upper‐class English background favored by English investment banks. For his bachelor's degree, Adoboli went to Nottingham Polytechnic and studied computer science rather than Classics. He joined UBS in an operations role and was later able to cross over to a trading role on the Delta One Desk,6 where he facilitated large client equity trades. He lived in an up‐market part of London and his work financed an expensive lifestyle. He was living the dream. Looking at Adoboli's profile in retrospect, one may wonder why he didn't stand out more from his colleagues. In reality, however, many of Adoboli's colleagues likely shared several aspects of this profile: his age, sex, lifestyle, and the aggressive, hard‐charging trading and work ethic. Slightly more unusual was his educational and work background in operations. However, it is the content of what Adoboli did at work, of course, that truly distinguished him from his colleagues. This is where any detective work should have come in. The fact that he was able to succeed in his deception for so long—some three years—highlights the difficulties involved in identifying such illicit activities.

The Crime of Rogue Trading

So what exactly is the Rogue Trader's sin? Traders are clearly paid by their employers to take risks. What exactly is wrong with the risks that the Rogue Trader takes?

Simply put, trading floors require traders to be supervised. Rogue Traders do everything they can to evade supervision. Rogue Traders tend to operate on trading desks responsible for facilitating client trades and, as such, are generally barred from taking risks with their own trades. Their clients tend to include institutions such as asset managers that buy and sell stock in bulk. A client may, for example, want to sell $1 billion worth of stock in a certain company. The job of the trader is to achieve the best price for his client. This requires speed and secrecy to prevent buyers from bidding the price down once they become aware of the seller. Clients pay their bankers large fees to make sure this happens. As a result, at a large investment bank, trading books of some of the traders working in institutional equities can be in the billions of dollars buying and selling the stocks in which they make a market for their customers. For such traders, there are huge levels of potential risk unless their positions are hedged—that is, matching of long positions (loss in market value hurts them) with short positions (loss in market value helps them) in equal amounts. Profit comes, then, not from changes in market values—they should be market neutral—but from the commissions and financing fees from the large trades they execute. Such traders are not supposed to make a lot of money in betting on the direction of a particular stock or group of stocks. There is too much risk involved for that.

In addition, in a typical investment bank, traders are generally limited to trading securities strictly within the scope of their “trading mandate.” An equity trader's mandate should be generally restricted to trading equities, a fixed income trader to certain fixed income products, and so on. A broad mandate is then defined down to a specific set of limits that a trader should trade within in order to restrict the potential losses that can be suffered from his book on any given day. This is called his VaR (value‐at‐risk) limit.7

Without limit management, given the number of traders and the size of their trading books in a large investment bank, banks potentially face catastrophic losses on any given day. Limits tend to be defined based on the level of experience and seniority of the trader and act to limit the potential size of a trader's profit for a day, a week, or a year, as well as his potential loss. Any trader who wishes to increase his profit opportunity can theoretically do so by increasing or exceeding his trading limits. While a Genius Trader may prevail upon management to assent to a temporary or permanent limit increase because he or she is a genius (discussed further in Chapter 3), no such privileges are likely to be extended to ordinary folk, the ranks of which are populated by the potential Rogue Trader. Such a trader will only be able to exceed his trade limits by deception—in other words, without authorization. He does this by various illegal methods of falsification and wrongful concealment of his tracks and activities. One can now see why this is such a serious offense and why it is labeled rogue trading. No trading operation can survive without defining such limits and requiring traders to stay within them unless otherwise authorized to do so. Trading without authorization is the source of the Rogue Trader's crime and is punishable with jail time, depending on the extent of the losses he causes to his employer. These can be very large when things go badly wrong because he is trading unsupervised as well as unauthorized.

Tools of the Rogue Trader's Trade

A trader seeking larger profit opportunities has to exceed his limits without seeming to—that is, through various means of deception. The basic objective is always to make sure that the trading book does not cause any unusual questions to be asked by supervisors, controllers, and limit checkers. In general this means making it appear that the trader's positions and risk levels are reasonably well hedged in line with expectations and prescribed limits. There are many tricks that may be employed in order to do this. Here are just a few that have been identified.

Intraday Trading

One opportunity traders on occasion take advantage of is the fact that their trading limits are generally set for the end of the trading day rather than intraday. The reason for this is simple: At the end of day, traders' positions are closed and static and therefore easily measurable. During the day, however, positions are constantly being updated and changed to reflect active trades and other transaction data. As a result, traders may execute trades in excess of their end‐of‐day limit during the trading day, either intentionally or unintentionally. As long as traders are able to bring their positions back down by day‐end, any intraday position excesses are normally unexamined. A deliberate strategy to trade beyond a trader's end‐of‐day limits by a considerable amount intraday is not necessarily easy to catch for the reasons just discussed. Furthermore, it is arguable, and has been argued by risk managers, that since the limit is an end‐of‐day limit, trading beyond it during the day is neither illegal nor unauthorized. While difficult to catch and prove, the extent of any loss is limited to those that can accumulate in a single day, which of course can be in the millions.

Phantom Trades

Another strategy a trader may employ is to modify the trading book prior to the supervisory and controller review at the end of the trading day (supervisors are expected generally to review trader activity at the end of the day). This can be done by creating nonexistent trades to balance out the real trades. Subsequent to the reviews, the trader cancels out the nonexistent trades and repeats such activities on a nightly basis.

Fake Counterparties

Another strategy has been to create fake counterparties to trade with, thereby allowing fictitious trades with that counterparty to be entered into his trading book to balance out the real trades. In all these cases, the trader creates an illusion of a hedged book. In reality, the book is anything but hedged.

Slush Fund

In order to allow such a strategy to work over a period of time, the trader needs to keep undue attention away from himself. He is thus likely to use a secret account that enables smoothing of profits over time so neither profits nor losses are overly excessive. Excess profits may be transferred to the secret “slush fund” account on good days and transferred back to the trading account on bad days. The creation and use of such accounts was a key point discussed at the trial of Kweku Adoboli. Such accounts normally can be created fairly easily though it may require controllers' help (knowingly or unknowingly) to evade their detection.

Developing expertise in or gaining access to back‐office systems in order to evade them then is a core part of the Rogue Trader's skill set. However, as we saw with the Rochdale case, a trader can sometimes do untold harm with one trade that gets through the system, which is well beyond the limits that can be borne by the firm. A small firm can have zero tolerance for such fatal trades whereas a large investment bank or hedge fund has most to fear from the type of rogue trading that took place at UBS.

How Rogue Traders Succeed

With gatekeepers at every step in the process of trade execution—supervisors, controllers, operations, counterparty operations—one might think that to elude them all is some sort of magic feat. While there is certainly some skill involved, it is not magic but a couple of crucial factors that enable some Rogue Traders to escape detection for so long (see Table 2‐1).

Table 2‐1 Infamous Rogue Traders

| Trader | Year | Loss (in US billions) | Firm | Years Undetected |

| Kweku Adoboli | 2011 | ∼$2.3 | UBS | At least 3 |

| Jerome Kerviel | 2007 | ∼$7.2 | Societe General | At least 3 |

| Nick Leeson | 1995 | ∼$2 | Barings | At least 3 |

First is the incentive structure still in place at investment banks. Traders' compensation has traditionally been binary and asymmetric, rewarding profit taking without punishment for losses and risky activities. Too often, management looks the other way to reward profits from risky trades. This is shortsighted. As history has shown, the winning trades of today are often the huge losses of tomorrow. Second is the problem of not big but “mega data.” Banks are drowning in data. Millions of trades are executed every day at the major investment banks. Even a small percentage of exceptions—trades that are canceled or corrected—is a few thousand on a daily basis, and so it is next to impossible to find the cancels and corrects of the Rogue Trader amongst the normal, regular, and benign flow of business corrections. In a similar vein, large investment banks trade with hundreds of counterparties; if one is fictitious, it will be very hard to find. Yet both these problems have their corollary in solutions.

Can the Rogue Trader Be Stopped?

It is likely impossible to completely stop Rogue Traders. What firms should aim for is minimizing the period of time such activity can go undetected and minimizing the extent of the losses.

First, incentive structures for traders should be reexamined. The practice of banks rewarding employees for risky trading activity should be eliminated. Instead, firms need to continue to reshape their culture to reflect the change in business strategy in the post–Dodd‐Frank world,8 which includes changing incentive structures. This includes, for example, deploying clawbacks9 on traders “swinging the bat” or making profits for trades in breach of agreed limits or outside the scope of their mandate. Additionally, incentive structures for traders whose job is to facilitate client trades rather than trade on the bank's own account, increasingly the norm in investment banks, should reflect their client relationship management objectives more clearly. Such incentive structures should reflect effective risk management and reward good citizenship. For example, traders identifying opportunities to improve the control environment or alerting management to risky behaviors on the floor, as well as delivering excellent client relationship management results, can be incentivized.

Second, trading systems and controls should be redesigned to reflect this change in culture and objectives. Investment bank systems have traditionally put traders at their logical center, maximizing features such as flexibility to allow traders to enter new clients and trades while bypassing certain controls. System design priorities in a Dodd‐Frank world need to reflect the twin priorities of clients and risk management. Putting clients and risk at the system's core enables management to organically track client limits and conflicts across the bank's business portfolio. Better understanding client needs and profitability across the platform—M&A advisory, lending, underwriting, asset and wealth management, sales, and trading—should also follow, and this will help to grow the business as well as manage risk more effectively.

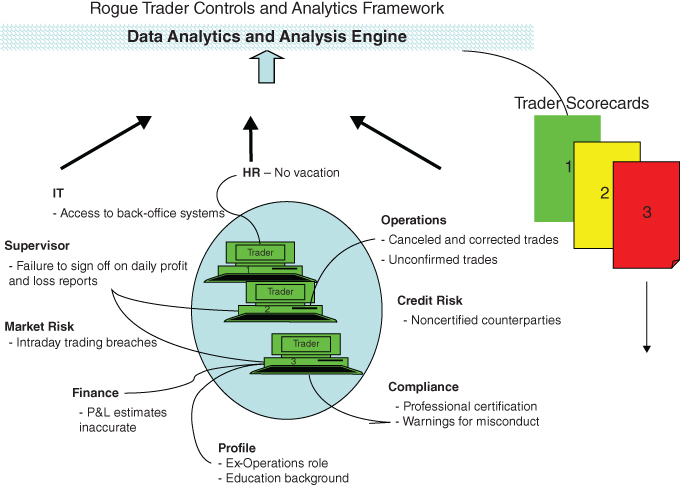

Third, banks should review their fraud detection methods and procedures. Big data can be the solution as well as the problem. It is clear from publicly available reports that Rogue Traders have been able to conceal their activities for several years at banks with, on the face of it at least, fairly well‐established operational risk functions and controls. It would seem, then, that more aggressive or more precise methods are called for. Retail banks and insurance companies have typically established dedicated fraud units and antifraud software to fight insurance fraud, cybercrime, and other types of fraud. Such methods are worth exploring in the investment‐banking world. Harnessing technology is, of course, already a big part of anti–rogue trading programs in investment banks in the form of trade surveillance, automated trade reconciliation, cancel and correct monitoring, and so on. Given the vast amount of data, however, in these different areas it is not clear how effective such tools can be on a one‐off basis in identifying suspicious activities. Algorithmic data mining and big data analysis could potentially be very useful in helping banks to connect the dots. Take, for example, a trader with several personal trading policy violations. Perhaps, on their own, these might not be sufficient to warrant any special investigation. But were this same trader also identified as someone who had moved from operations to the front office, had not taken mandatory leave,10 and had also accumulated unusual levels of trading profit on a client facilitation desk, such a combination might easily make the trader a candidate for a deep‐dive investigation. In the large and complex world of the modern investment bank, such triggers can probably only be pulled with applications based on investment in intelligent and natural learning. Figure 2-1 highlights some of these indicators.

Figure 2-1: Indicators of Rogue Trader risk

Fourth, banks need to continuously review the checks and balances established to prevent and mitigate rogue trading behaviors. Many banks did just this in the wake of the recent UBS/Adoboli incident in 2011. The key checks include, inter alia:

- Mandatory vacation policy—this was introduced in investment banks to ensure the ability of supervisors to independently take a look at every traders' book during their annual leave, something that never happened with Kerviel at Societe Generale.

- System entitlements—traders should not be entitled to edit operational systems, as this could be a way for them to manage their back‐office accounting.

- Segregation of duties—there should be clear separation of duties between traders, operations, and accounting to ensure that traders are not in a position to manipulate their accounts, confirmations records, etc.

- Trade‐limit monitoring—a separate risk management function should be reviewing trade limits and ensuring that traders stay within theirs.

- Independent valuation and profit and loss reviews—traders should not provide the valuation of their trades and position; there should be an independent function doing so.

- Confirmation procedures—banks should make sure there are independent confirmation procedures to ensure that the bank is able to verify that the traders' trades are genuine.

Technology has a big part to play in making such reviews effective and efficient. Consider system entitlements, for example. Investment banks today deploy so many systems, and within these systems, so many different roles and responsibilities, that without specifically designed tools and intelligent automation, it is impossible to track whether an individual has the system entitlements needed to do his or her job. In such an environment, without well‐designed exception tracking and reporting, it is easy to see how an individual could accumulate entitlements to systems that will help support a scheme with nefarious objectives.

In summary, the controls against rogue trading in an investment bank comprise a combination of cultural change and intelligent or cognitive system reengineering. It is likely impossible to stop Rogue Traders altogether, but significantly reducing the duration of undetected periods of activity and the size of the consequent losses is a reasonable objective. Executing the strategies discussed here to transform the culture and technology of investment banks will help support the achievement of that goal.