CHAPTER 4

The Austrian School of Economics

Although it was 10 years into my career as an investor before I came across the Austrian economists, discovering them was a major turning point. Their ideas on economics have gone on to provide me with an explanation for economic developments which has proven to be surprisingly coherent with my day-to-day experience in the markets and my work as an investor. They have been marvellous companions along the way. I therefore feel it's logical to devote a chapter to them, even if it may seem a little unorthodox in a book ostensibly about value investment.1

Being an expert in economics is not an essential prerequisite for daily investment decisions, but it is definitely useful to have a sound conceptual framework to fall back on; a sufficiently nuanced understanding of economics provides us with some orientation. Indeed, nowadays, I find it very difficult to convey even basic investment concepts without having first established a robust economic framework.

Even though there are hundreds of hedge funds attempting to second guess the direction of the economy, most value investors don't think about it very much, spending practically no time on forecasting. The latter believe that they add their value through selecting companies. We could even go so far as to say that a lack of interest in the economy is a defining feature of a value investor.

And rightly so, because trying to guess what the economy will do next is tantamount to taking a stab in the dark about how millions of people will behave, particularly the ruling political class, which as we know is almost impossible.

That said, experience has shown that understanding how the so-called economy works, which is no more than understanding human behaviour, can be of significant help in the process of investing for the long term. Investment is about trying to predict the behaviour of consumers, entrepreneurs, workers, politicians, and everything that surrounds us. If we understand their driving impulses and what we can expect from them, then we will already be some of the way down the road. The economy and investment are intimately linked. Not because both disciplines deal in numbers, which to a large degree are superfluous, but because at heart they are about understanding human behaviour. This is the ultimate goal of all good economists and investors.

Fortunately, there is a branch of economic theory that is of particular help to us in this endeavour. In the Austrian School we find what the classists called ‘the economy and its economists’. I'm not talking about sorcerer's apprentices, but rather down-to-earth, perceptive individuals able to explain an array of human behaviour, particularly in relation to the economy. This economy and its economists will not tell us how much GDP will grow by next year, nor what inflation will do, but it can alert us to what might happen in a country or a particular sector over time based on how different economic actors are currently behaving. A warning of where the dangers might lurk and where it's safe to swim. Ultimately, it will provide us with a set of critical variables to hone in on. The latter almost never coincide with what your run-of-the-mill, neoclassical economists consider to be important.

This chapter will therefore focus on this group of marginalised, outcast, and oft-forgotten Austrian economists, with the aim of demonstrating how understanding human action in the economy can enable us to see the future more clearly and live the present moment with greater peace of mind.

I could have simply limited myself to recommending Ludwig von Mises' superb Human Action2 or Murray N. Rothbard's History of Economic Thought,3 but both run to more than a thousand pages and I don't want to put anybody off. Furthermore, given their significance to my tale, I feel that the Austrian School deserves more than a simple footnote in this book.

What follows is an attempt to provide a brief overview of the school and its main tenets, based on Huerta de Soto, Jesús's excellent primer, The Austrian School.4 I will finish up by discussing possible applications for their ideas to investment.

BRIEF HISTORY OF THE AUSTRIAN SCHOOL

Origins

The Austrian School formally came into existence in the nineteenth century with Carl Menger and the subjectivist revolution brought about by the publication of his Principles of Economics.5 But the basic ideas of the school go back even further and have their historical antecedents in Taoism, as highlighted by Rothbard.

By then, the Roman legal tradition had already been developed on the basis of accumulated customs and the evolutionary development of institutions – a key focus of attention for Friedrich A. Hayek – and its formation and development continued with contributions from successive generations. As Huerta de Soto, Jesús recalls, Cato observed that:

In contrast, our Roman republic is not the personal creation of one man, but of many. It has not been founded during the lifetime of any specific individual, but over a number of centuries and generations. For there has never been in the world a man intelligent enough to foresee everything, and even if we could concentrate all brainpower into the head of one man, it would be impossible for him to take everything into account at the same time, without having accumulated the experience which practice provides over the course of a long period in history.

(in Jesús Huerta de Soto's Austrian School)

The timelessness of these words speaks for itself, and they have been developed over time by numerous thinkers, culminating with Hayek in the twentieth century. After the Romans and following the Thomistic traditions, various Spaniards belonging to the Salamanca School during the Spanish Golden Age made critical contributions to what – centuries later – would become Austrian thought. In fact, Hayek regarded them as the main pioneers of market economy theory. The key thinkers in the Salamanca School were: Diego de Covarrubias, Luis Saraiva de la Calle, Luis de Molina, Juan de Lugo, Juan de Salas, Juan de Mariana, Martín de Azpilcueta, and some others. An array of stars who created and discovered concepts such as the subjective theory of value, the appropriate relationship between prices and costs, the dynamic nature of markets, the resulting impossibility of reaching economic equilibrium, the principle of time preference, and the distortionary nature of inflation. Evidently, the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century members of the Salamanca School had their heads more firmly screwed on than most twenty-first-century economists, including various Nobel Prize winners.

However, following their demise the subjectivist school fell into decline, which was partly the doing of Adam Smith. The renowned father of modern economics made some exceptional contributions, but he distanced himself from the subjectivist tradition, developing an objective labour theory of value and assigning great importance to the natural price equilibrium.

The labour theory of value subsequently formed the basis for Marx's ideas. As Rothbard would later argue, the development of economic thought is far from linear, as is the case in physical sciences, but it instead moves in constant fits and starts.

Nonetheless, some farsighted economists kept the subjectivist flame alive during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In particular, Cantillon, Turgot, and Say in France; and Jaime Balmes in Spain. Say, for example, developed the famous Say's Law, which states that supply creates its own demand; the income from selling our products enables us to demand other products that appeal to us. This simple idea was misconstrued by Keynes a century later when he developed the erroneous concept of insufficient demand, the idea that demand in an economy can be less than supply, requiring artificial stimulation. Unfortunately, this nonsensical notion has stayed with us to this day, continuing to wreak the same damage as it has done over the centuries.

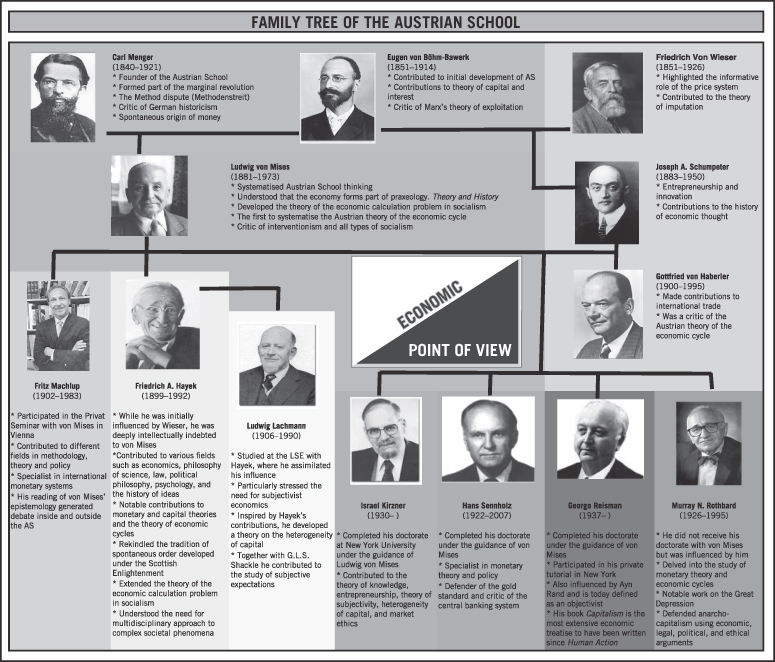

Source: puntodevistaeconomico.wordpress.com.

Carl Menger

Carl Menger (1840–1921) encapsulated the essence of these historical predecessors, and in his methodological struggles with the German historicists created the foundations of what would become the modern Austrian School. He advocated a priori logical analysis over the study of history and empirical data.

His book Principles of Economics constructs an economic theory based on tangible, creative human beings, in contrast to the objective theoretical beings invented by Adam Smith and Marx. His theory culminated in the law of marginal utility, which states that the value of each marginal unit diminishes in accordance with the end objectives and available means.

Another essential contribution is his theory on the origin and development of the social institutions – linguistic, economic, and cultural. He addresses the question: How is it possible that the institutions which are most significant to and best serve the common good have emerged without the intervention of a deliberate common will to create them? His conclusion is that these institutions appear over time as a result of human interactions, and that these interactions are precisely the main purpose of studying economics. Money is one of the main institutions to which he applied his evolutionary analysis.

After Menger came Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk (1851–1914), who expanded the subjective theory to capital – becoming the first to provide a very extensive explanation for the time structure of production – and to the theory of interest.

His interest theory was the first to employ the concept of time preference as the basis for determining the interest rate, broadening beyond mere monetary exchanges.

Finally, and of particular interest to us, he was the first author to reflect on the psychological component hampering ‘correct preference’ formation, highlighting the excessive weight assigned by human beings to the present, and inconsistencies in elections. He was the forerunner of behavioural finance, which has become such a focus of interest in recent decades.

Hot on their heels came perhaps the most important thinker in the Austrian School: Ludwig von Mises.

Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig von Mises (1881–1973) was born in Lemberg, in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He became an economist after reading Menger's Principles of Economics. And, after attending a seminar by von Böhm-Bawerk in Vienna, he began lecturing there and later in Geneva. When the Nazis rose to power he was forced to flee to the United States, giving classes at New York University. His contributions were defining.

In his theory of the value of money and, especially, through his regression theorem, he established that today's demand for money is based on yesterday's valuation of money, and yesterday's valuation was based on the previous day's, and so on until the moment of very inception when an original commodity – such as gold – was first used as money.

In his insightful theory of economic cycles, he highlights how cycles originate from the creation of credit without prior savings, through a fractional reserve banking system – not supported by gold – and with the acquiescence of central banks. On this basis, banks grant long-term loans using short-term deposits provided by clients. Since the bank does not maintain all the necessary money in the account to pay the depositor, it conjures money ‘out of nothing’. Huerta de Soto, Jesús explains in Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles6 that the bank breaks its deposit contract with the client by lending their money to a third party. On this point and others, there are some disagreements between members of the school. There is no uniform viewpoint – just like in any other school of thought.

In his theory on the impossibility of socialism, von Mises starts with the premise that nobody is capable of accumulating perfect knowledge and information on everything that is being created in a dynamic economy at a given point in time. The need for countless assessments of different economic agents' ends and means makes it impossible to adjust the available resources to their desired goals. All of this is beyond the capabilities of a single person or a group of wise men, and attempting to do so only leads to extreme disorder in human actions in the economy. Accordingly, in his entrepreneurship theory, he portrays humans as tangible, free, and creative beings, acting as the protagonists in a dynamic social process.

Von Mises was responsible for creating the Austrian Institute of Economic Research, which, led by Hayek, was the only one to predict the catastrophe that would take place after 1929. He even went so far as to turn down an offer of work in the Austrian Kreditanstalt because of his concerns about their situation.7

Meanwhile, one of the leading lights of the neoclassical school, Irving Fisher, was quoted as saying in 1929 – with astonishing naivety – that ‘stock prices have reached what looks like a permanently high plateau’.8

In 1949, von Mises penned his masterpiece: Human Action, which is the Austrian School's most important book. It is an inspiring read, and I highly recommend it to anyone who wants to dive into these issues in more detail.

Friedrich A. Hayek

Friedrich A. Hayek (1899–1992) was von Mises' most brilliant student. Hayek was the one responsible for introducing me to the Austrian School. In 2000 I came across his book The Road to Serfdom,9 which had a major impact in the aftermath of the Second World War, despite not being his best work. He definitively won me over with his last book, The Fatal Conceit.10 The book provides a superb overview of his thinking, especially in relation to the creation and development of institutions and the spontaneous order of the market.

Hayek was also born in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in Vienna. Initially inclined towards holding socialist views, he abandoned them after reading von Mises' Socialism.11 He became a disciple of the former and brilliantly took forward his work. He completed von Mises' explanation of the cycle, emphasising the importance of interest rate manipulation.

Artificial credit creation with low interest rates is the main driver of unchecked economic booms, which inevitably end in painful recessions, severely correcting previous excesses. In applying his theory in 1928 he was able to predict the crisis to come: the Fed tried to offset price falls driven by the enormous increase in productivity in the 1920s through lowering interest rates. The Fed failed to realise that this decline in prices was natural, and thus did not need to be fought, in turn provoking an excess of liquidity in the system. (Something similar happened in 2015, although with less of an increase in productivity.) Surprisingly, when – mainly neoclassical – economists and historians analyse the depression of the 1930s, Hayek is barely mentioned, even though he was engaged in intense intellectual arguments with Keynes, Milton Friedman, and the Chicago School – and, of course, with ‘socialists from all parties’.

In his brilliant evolutionary theory on institutions, he reinforced the idea that society is not a system rationally organised by a human mind, but rather a complex process arising from an ongoing natural evolution that cannot be consciously managed. Society has its own dynamic and spontaneous order, impossible for a single person to improve through conscious management, as nobody has the information available to do so. Furthermore, to do so would involve significant coercion, preventing each individual from freely pursuing their own ends.

Outside of the strictly economic realm, Hayek also engaged in significant research on rights and the nature of laws. In particular, the concept of liberty as freedom from constraints and justice as equality in the eyes of the law. These concepts have often been perverted by individual interest groups.

Murray N. Rothbard

Murray N. Rothbard (1926–1995) was another of the Austrian School's exceptional thinkers, making very important contributions – such as the previously mentioned History of Economic Thought, or America's Great Depression,12 which provides a brilliant explanation of the causes of the American depression of the 1930s.

Huerta de Soto, Jesús

Spain also has its own leading light in the Austrian School, in the form of Huerta de Soto, Jesús, who has undertaken important work in developing various areas, as well as doing a great job in explaining the main ideas of the school in his introductory book, The Austrian School.13 Also worth highlighting is his enlightening book Money, Bank Credit and Economic Cycles,14 which is a great aid in understanding these joyous economic cycles.

MAIN TENETS OF THE AUSTRIAN SCHOOL

Huerta de Soto, Jesús sets out the main tenets of the School in his book on the same subject, as well as the main differences to the neoclassical schools, whether Keynesian or Monetarist. The comparison in the table below is both necessary and enlightening. The neoclassical school dominates current economic thinking, despite having proven incapable of helping us to smoothly navigate our collective life.

| Points of comparison | Austrian paradigm | Neoclassical paradigm |

| 1. Concept of economics (essential principle): | A theory of human action understood as a dynamic process (praxeology). | A theory of decision: maximisation subject to restrictions (narrow concept of ‘rationality’). |

| 2. Methodological outlook: | Subjectivism. | Stereotype of methodological individualism (objectivist). |

| 3. Protagonist of social processes: | Creative entrepreneur. | Homo economicus. |

| 4. Possibility that actors may err a priori, and nature of entrepreneurial profit: | Actors may conceivably commit pure entrepreneurial errors that they could have avoided had they shown greater entrepreneurial alertness to identify profit opportunities. | Regrettable errors are not regarded as such, since all past decisions are rationalised in terms of costs and benefits. Entrepreneurial profits are viewed as rent on a factor of production. |

| 5. Concept of information: | Knowledge and information are subjective and dispersed, and they change constantly (entrepreneurial creativity). A radical distinction is drawn between scientific knowledge (objective) and practical knowledge (subjective). | Complete, objective, and constant information (in certain or probabilistic terms) on ends and means is assumed. Practical (entrepreneurial) knowledge is not distinguished from scientific knowledge. |

| 6. Reference point: | General process which tends towards coordination. No distinction is made between micro- and macroeconomics – each economic problem is studied in relation to others. | Model of equilibrium (general or partial). Separation between micro- and macroeconomics. |

| 7. Concept of ‘competition’: | Process of entrepreneurial rivalry. | State or model of ‘perfect competition’. |

| 8. Concept of cost: | Subjective (depends on entrepreneurial alertness and the resulting discovery of new, alternative ends). | Objective and constant (such that a third party can know and measure it). |

| 9. Formalism: | Verbal (abstract and formal) logic which introduces subjective time and human creativity. | Mathematical formalism (symbolic language typical of the analysis of atemporal and constant phenomena). |

| 10. Relationship with the empirical world: | Aprioristic deductive reasoning: radical separation and simultaneous coordination between theory (science) and history (art). History cannot validate theories. | Empirical validation of hypotheses (at least rhetorically). |

| 11. Possibilities of specific prediction: | Impossible, since future events depend on entrepreneurial knowledge which has not yet been created. Only qualitative, theoretical pattern predictions about the discoordinating consequences of interventionalism are possible. | Prediction is an objective which is deliberately pursued. |

| 12. Person responsible for making predictions: | The entrepreneur. | The economic analyst (social engineer). |

| 13. Current state of the paradigm: | Remarkable resurgence over the last 25 years (particularly following the crisis of Keynesianism and the collapse of real socialism). | State of crisis and rapid change. |

| 14. Amount of ‘human capital’ invested: | A minority, though it is increasing. | The majority, though there are signs of dispersal and disintegration. |

| 15. Type of ‘human capital’ invested: | Multidisciplinary theorists and philosophers. Radical libertarians. | Specialists in economic intervention (piecemeal social engineering). An extremely variable degree of commitment to freedom. |

| 16. Most recent contributions: |

|

|

| 17. Relative position of different authors: | Rothbard, von Mises, Hayek, Kirzner. | Coase, Friedman, Becker, Samuelson, Stiglitz. |

As can be seen, there are numerous and very distinctive differences both in terms of methodology and approach. Some of the key differences are as follows.

The Austrian paradigm is based on a ‘theory of human action’, which is understood to be an ongoing dynamic and creative process. The objectives to be met and the means to achieve them are not given, nor can they be established at the outset as they are continually changing as a result of an ongoing process of action and reaction among economic agents. Mankind is therefore the main actor in a never-ending process, which never reaches equilibrium – von Mises' ‘stationary state’ – since there will always be other actors whose actions shatter the expected equilibrium, contributing new elements in the process. The main protagonist is the creative entrepreneur who tries to capitalise on market disorder to earn a profit by offering a product or service at the lowest possible cost. This contributes to channelling market processes towards an equilibrium which evidently is never fully attained.

As Huerta de Soto, Jesús puts it:

The fundamental economic problem which the Austrian School seeks to address is very different from the focus of neoclassical analysis: Austrians study the dynamic process of social coordination in which individuals constantly and entrepreneurially generate new information as they seek the ends and means that they consider relevant within the context of each action they are immersed in and, by so doing, they inadvertently set in motion a spontaneous process of coordination.

The protagonist, the creative businessmen or entrepreneur, is the hero in our story, who sacrifices their savings to fulfil a new need, or to take a different approach to resolving an existing need. They take on this risk without knowing if they are making the right decision; it is worth recalling that 90% of companies do not survive past three years. When a successful entrepreneur is criticised for obtaining large profits, it is worth remembering the countless mistakes made by the entrepreneur themselves and others before them, which underpin the success and have helped contribute information.

Crucially, this entrepreneur can make pure errors, resulting from a failure to properly forecast the future in terms of demand and prices, or in terms of costs. Since information is always partial and subjective and constantly being created by economic actors, it is impossible for anyone to have full certainty about what is happening and even less so about what will happen. Therefore, specific forecasts are impossible, given that they depend on knowledge which in most cases has not yet been created. The only thing an entrepreneur can do is make general predictions, which will have a greater or lesser chance of being fulfilled in accordance with the rationale underpinning the a priori analysis, which ultimately is an inward-looking analysis of events, or – in other words – a personal reflection on how reality works on the basis of a small number of axioms which are irrefutable in any situation (for example, you cannot act and not act at the same time).

Although the Austrian economists made some successful forecasts, trying to predict the future is a very common conceit: searching and believing that causal relationships have been found which do not exist, and overlooking the existence of completely unpredictable but recurring phenomena, as Nassim Nicholas Taleb explains.

That is why the Austrians regard ‘applying natural sciences methods to social sciences to be a basic error of enormous severity’. In economic science there is no such thing as constant or functional relationships, because we are analysing human behaviour – human actions – with an innate and infinite creative capacity. As Newton put it: ‘I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people’. He was referring to the South Sea Company stock market bubble in 1720, which he suffered first-hand.

Source: Grantham, Mayo.

Another point of focus for Austrian theory is ‘the concept of cost’. For Austrian economists, costs are subjective, as Huerta de Soto, Jesús explains: ‘Cost is the subjective value the actor attaches to those ends they give up when they decide to pursue a certain course of action’. In other words, costs are not objective and given, but are instead discovered through action and, evidently, vary in each moment depending on the circumstances and alternatives. Ultimately, it is an opportunity cost. What do I forgo doing with the resource I am using: material, time, work, etc.?

These are the most important concepts from an investment perspective, but it is worth emphasising that the school has a very extensive body of work, covering practically every field that may be of personal interest to us. I am not completely in agreement with all the ideas that have been developed – for example, Rothbard's curious theory regarding the legitimacy of blackmail, which states that with available information we can act as we see fit, and with blackmail we give a last opportunity to the person being blackmailed – but on balance I think the Austrian School's ideas explain a large part of the reality of our existence.

APPLICATIONS TO INVESTMENT

What we have discussed so far might seem like an irrelevant theoretical confab, far removed from the world of investment. Nothing could be further from the truth. Admittedly, it won't tell us much about where stock prices will be next month or year, nor which emerging sector will take off in the years to come, nor what GDP growth is going to be like in one country or another. But it does help provide some perspective on the economic backdrop, a bird's eye view of sorts, and therefore perhaps a somewhat better understanding of what is happening: for example, which countries are taking the right steps or which sectors may be receiving too much capital, and therefore which countries stand to reap rewards in the future and which sectors are likely to encounter difficulties generating decent medium-term returns.

What follows are some of the Austrian School's main ideas, which I find to be particularly applicable to the investment process.

1. Markets work, by definition. The markets are formed of millions of people interacting with each other, made up of entrepreneurs with different goals and means, which only they can fully grasp. Meddling in these interactions artificially distorts the market, creating different results which are inferior to those intended by the people involved. It is possible that intervention may achieve better outcomes in the short term for the individuals responsible for it, but the overall results are worse for society as a whole since they are not freely chosen by them.

The accepted mainstream economic wisdom is that the market fails on a regular basis – imperfect competition, externalities, public goods, etc. – and this needs to be corrected. However, it's not clear how the market is erring when people are freely pursuing their own objectives, successfully or otherwise. In general, correct definition of property rights resolves such ‘failures’. But even if we accept that market failures exist, how do we know that the solution is going to be better than the original error? In fact, any solution is ultimately going to come from people who similarly have their own errors to overcome. The discussion can go on for ever.

My experience is that the more intervention there is, the most disorder there will be. This can reach the level of chaos in state-managed economies, as was the case in the Soviet Union. This is further exacerbated by the fact that intervention is normally accompanied by arbitrary legal action: justice is not the same for everyone.

Real-world application: the greater the intervention, the less economic growth and legal security there will be, leading to greater reluctance to invest in the economy. A surprising example is Brazil. I have always been puzzled as to why Brazil, despite its great development potential, has been blighted by high interest rates as a result of persistent inflation. I discovered the problem for myself in my only trip there in 2010: the economy is subject to excessive levels of intervention, controlled by a hotchpotch of pressure groups. Companies demand tariff protection and they are granted it; workers demand protections which cannot be sustained by their productivity and they also get their own way. Furthermore, the politicians are unable to reach an agreement on dismantling the bloated government bureaucracy (the automobile company Fiat employs 1,000 people just to present multiple tax declarations). This excessive intervention leads to countless bottlenecks, resulting in inequality and imbalances, with certain social groups obtaining excessive income, while others languish amid high inflation and stagnant growth. The new government seemingly wants to put an end to public spending growth, and reform labour laws and the tax mess; time will tell whether they are successful.15

China is the opposite case. Despite supposedly being a socialist economic system, government intervention – as already noted – is largely absent from a broad spectrum of the economy, unleashing such fierce competition that the economy has been able to grow rapidly without inflation.

Intervention in the money markets warrants special attention. We will discuss the harmful consequences of such intervention, which progressively dilutes the value of money, in more detail later on. Indeed, the extent to which there is monetary intervention is potentially a useful predictor of long-term exchange rates. While it is impossible to say anything meaningful about the short term, a high degree of intervention is a probable signal of long-term currency depreciation to come.

2. Markets are never in equilibrium. Markets are locked in a constant and never-ending process, and there will always be an entrepreneur attempting to exploit new knowledge or temporary disorder to offer a product at an attractive price and reasonable cost. The presence of alert entrepreneurs makes it very difficult, and sometimes impossible, for a company to sustain exceptional profits over a long period of time. There will always be somebody attempting to copy a good idea which generates high returns on capital employed.

As such, there are very few companies able to maintain a durable competitive advantage, and such advantages tend only to be time-limited, because knowledge developments inevitably provoke unpredictable changes. The flipside is that this also implies that nothing lasts for ever. Sectors in crisis with an excess of capital will sooner or later experience capital outflows, improving the situation for those left behind.

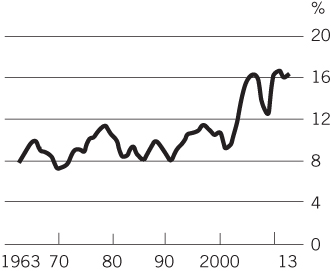

Accordingly, nearly all sectors end up reverting towards a reasonable return on capital, which is neither high nor low – between 5% and 10%, although in recent years it has been above the historical average. This rewards risk-taking and investors' willingness to forego their time preference.

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis; Federal Reserve; Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies (6th edn), McKinsey Corporate Performance, August 2015.

Real-world application: investors need to be conscious of excess or insufficient returns in a specific sector, patiently waiting for the situation to change. The clearest example are cyclical companies whose business is subject to ups and downs in supply and demand, with knock-on effects on returns. In any case, the goal is to find companies who obtain high returns because of competitive advantages, but in doing so it is vital to understand where these returns come from and whether they can be sustained over time.

These first two ideas – the idea that markets work and that they are always in the process of seeking equilibrium – and their corresponding applications, may seem self-evident. However, it would seem to be less clear to mainstream schools of thought or analysts talking up their own sectors. In reality, both principles must not only be recalled, but also emphasised.

3. Economic growth is fundamentally based on increases in productivity resulting from division of labour, financed by savings. The ‘extended order’, as Hayek refers to it, is what facilitates this division of labour, enabling us to organise ourselves and develop trust beyond the limited confines of our family or clans. An increase in savings and productivity is facilitated by a favourable institutional framework, where stability predominates.16 The legal framework is therefore essential to ensuring that the consequences of our behaviour are predictable: the rule of law must be real and effective.

Real-world application: after having carefully analysed the type of growth being experienced by one country or a group of countries, it is crucial to determine whether such growth is solid – based on savings and productivity – or unstable – built on credit and plunder.

Until 2009, Chinese growth was supported by strong increases in productivity, overseeing the inclusion of millions of people into the market and with very high savings rates. This happened because of an increasing rollback of intervention in the market and a degree of legal stability. There were exceptions in strategic sectors, though this is hardly uncommon in the rest of the world. Since 2010, the increase in leverage, reflecting insufficiently developed capital markets, has raised doubts about China's growth model, although my perception is that entrepreneurial creativity will outweigh relative debt excesses in the future.

The polar opposite has happened in Spain. In the first decade of the twenty-first century growth was fuelled by massive indebtedness. When it became clear that this unbalanced growth was unsustainable, there was a sudden blowback from failed projects, which brought about a sharp adjustment in labour and land costs. This correction helped realign factors of production with their underlying productivity, putting growth on a healthier and more sustainable footing, with a progressive reduction in debt levels.

I was particularly sceptical about the alarms that were being raised about China prior to 2009, because I understood that China's development was taking place because of a deepening of the markets, and we invested in companies able to capitalise on this, such as BMW, Schindler, and others. I have become more wary since 2010, but I still remain reasonably upbeat.

By contrast, in Spain, after having refrained from investing in sectors closely linked to the economy for various years, in 2012 we started investing again after noting a healthier pattern of growth.

4. Time is an essential aspect of the Austrian explanation of the productive process, which is about making an immediate sacrifice for the development of greater future productive capacity and an increase in productivity. Production is not instantaneous and this process needs to take place over various phases, ranging from the use of essential materials – land, gas, etc. – to the products consumed at the end of the chain.

Real-world application: our investment process should look beyond the immediate satisfaction of our consumption – and subsequent investment needs. We should save and sacrifice immediate returns when beginning to invest. We will only reap the rewards if we can see beyond the initial moment of investment.

The parallels between a healthy long-term productive and investment process are evident and aesthetically glaring.

Sacrifice is a crucial element of the process, but as we will see in Chapter 9, it runs contrary to our nature; we are not wired that way. A deep understanding of the functioning of the economy – how humans behave – will help with this approach, especially when the investment community is typically extremely myopic.

5. A particular type of intervention in the money market is especially important: currency manipulation through the control of interest rates by central banks. This generates significant distortions in the credit market, investment excesses, and financial bubbles, which result in the creation or exacerbation of economic cycles, which can become especially pronounced and elongated. Central bankers do not possess exceptional knowledge enabling them to accurately determine monetary conditions or set the right interest rate; their only advantage is having access to relevant information 15 days before other operators. And not only this, but they are tied by political and personal bonds, which undermine their independence when it comes to taking decisions. It is very difficult to escape consensus or conventional thinking when one's professional career is on the line.

In truth, an interest rate based on the decisions made by all market actors would be a better reflection of the needs at any given time, as implicitly acknowledged by Alan Greenspan, the most famous central banker in recent decades: ‘I said that I was still worried why share prices were too high, but that the Fed would not be able to second guess the movements of “hundreds of well-informed investors”. By contrast, the Fed took a position aimed at protecting the economy from the eventual crash’.

Here Greenspan is not referring to bond investors, who determine the price of money, but to equity investors. However, there is no way to distinguish one group's knowledge from another. Thus, following his reasoning, it is also not logical to ‘second guess’ the movements of ‘hundreds of well-informed fixed-income investors’ and thus try to control interest rates – as the Fed does.

Real-world application: investors should steer clear of economies whose growth is based on credit creation under the auspices of low interest rates established by central banks. This was how we avoided permanent capital losses during the 2006–2007 financial bubble. We had practically no exposure to the real-estate and financial sectors.

Perhaps the most instructive example of the impact of intervention on an economy in the twentieth century is the different policy approaches employed by authorities in the United States during the 1921–1922 crisis and the 1929–1945 depression. In the former, the market was allowed to freely adjust, eliminating bad investment and the crisis was overcome within months. However, in the 1930s, after having maintained an excessively lax monetary policy at the end of the 1920s, a second major error was made – as explained by Hayek at the time: free price formation was not permitted – the essential market adjustment mechanism. Wages were frozen while product prices were in freefall. The result was a build-up of losses across a multitude of companies and an inevitable flurry of insolvencies. It was only after the Second World War that the controls introduced by Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt were dismantled and an impressive post-war economic boom ensued.17

In 2016, at the bidding of their political masters, central banks continue to aggressively manipulate rates. Thankfully, the hangover from the previous crisis means that this money creation is not clearly flowing out of the financial system into the rest of the economy; but this could change at any moment, leading to a significant loss of currency value and consequent hyperinflation.

6. The economy's natural state is deflationary, when there is no artificial boosting of the amount of money in circulation. Productivity increases enable more goods to be produced for the same amount of money. This is positive for the consumer, who benefits from a continued reduction in prices relative to wages, as has been the case for computers or telephones.

The strongest growth in the American economy's history took place from the end of the civil war up to the completion of the nineteenth century. These 30 glorious years were characterised by pronounced deflation. Admittedly, there have also been two well-known deflationary processes which have been accompanied by continued recessions, as we have seen in the United States in the 1930s and in Japan during the last 25 years. Nonetheless, in Japan, per capita growth has been positive and similar to that of other developed economies; the essential problem there is the lack of population growth. The causes of the Great Depression in America have already been discussed and can be found in the successive interventions which prevented the price of production factors from adjusting to their underlying productivity.

Recently, there have been instances of deflation and strong growth in Spain, Ireland, and the Baltic States. Spain, for example, has just seen three years of deflation, from 2013 to 2015, which has been accompanied by economic growth of 2%.

In truth, deflation is not a cause of stagnation but rather a symptom and part of the solution to the problem. In Spain, it was clear that labour and real-estate costs had risen beyond fair value and the economy did not recover until they returned to market levels. 25 years ago Japan was the most expensive country in the world, and it's highly plausible that this was part of the problem that had to be addressed, along with excessive intervention in large sections of the economy, the lack of meritocracy, and the demographic problem.

It's common to read and hear about the dangers of deflation, but these tend to be more invented than real: they don't create a liquidity trap, nor mass unemployment, nor a fall in output.18

So why is there so much fuss about deflation? These warnings are mainly sounded by governments, who are generally indebted19 and stand to lose from deflation. The weight of debt increases with deflation. The amount of debt remains constant, but money gains value because it can buy more things and, accordingly, more effort is needed to pay back the debt. By contrast, inflation makes debt repayment easier. So which will the state and its associates prefer – inflation or deflation? The answer is obvious.

Source: McKinsey Global Institute (3/16) IMF.

Real-world application: the most likely outcome in an economy subject to state intervention is high inflation. The government is judge and jury and unsurprisingly rules in its own interest. It is therefore best to be prepared by investing in real assets: public or private shares, houses or commodities. Always. We will discuss this in more detail in the next chapter.

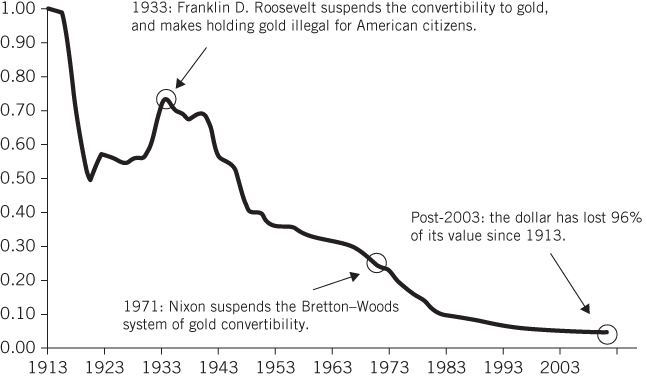

7. The absence of a currency linked to gold – or a similar commodity free from political decision – means that the currency will permanently depreciate in relation to real assets. This has always been the case and will continue that way. Government pressure for currency depreciation is unrelenting.20

Source: BLS IPC Data.

Real-world application: once again, it is best to only invest in real assets, aside from occasional liquidity needs. I repeat, always. We will also go into this issue in the next chapter.

8. Product prices – which depend on consumers' willingness to pay – determine costs and not the reverse, as many people think. It's surprising how widespread this misconception is. For example, the Financial Times' ‘Lex’ column, the most prestigious global financial column, has made the same error on more than one occasion.

The Bernstein analyst, Paul Gait, has analysed the issue for mining companies, observing that the correlation between costs and prices in the previous period is very high. The price ended up determining costs over the next two years.

Source: estimates and analysis by Wood Mackenzie, AME, Bloomberg LP, and Bernstein.

Thermal coal and oil are clear examples of two commodities where recent falls in costs followed prior declines in prices.

Source: Wood Mackenzie, Morgan Stanley Research.

Source: Bernstein analysis and estimates.

Real-world application: marginal costs – associated with the final and most expensive producer – are constantly changing in line with the scale of demand. If the demand for oil is 80 million barrels a day and barrel number 80 million costs 100 dollars to produce, then the market price will be 100 dollars and everyone who is able, will produce at a cost below 100 dollars. If the demand falls to 50 million barrels, the marginal price will also fall, and so, if the marginal producer who produces barrel number 50 million does so at a price of 40 dollars/barrel, the market price will be 40 dollars and it will only be produced by those who do so below 40 dollars. If the demand falls to 0 barrels, the cost will be 0 dollars and nobody will produce. It seems obvious, but not to everyone.

Investors should not forget the order: first demand is calculated, then the costs necessary to meet that demand.

9. Production costs are subjective, meaning that any production structure is liable to vary depending on the circumstances. Cost is equal to my best alternative. Since these alternatives are variable and subjective, the cost is also variable and subjective.

Real-world application: do not take costs as given. This is a common error when looking at commodity or cyclical companies, or companies with novel products. Costs continually vary in accordance with changing market conditions or technological developments. A lot of engineers have found themselves out of work following the decline in oil prices in 2014 and 2015, reducing their options and meaning that they are willing to work for less money, reducing mining costs. The same effect has come from the development of shale oil and gas in the United States, which is an alternative technology that has facilitated a reduction in the costs of producing a marginal barrel.

10. Economic models are – to all intents and purposes – useless. Attempting to model unpredictable human behaviour and probable, but unknown, future events is impossible. The best we can manage are limited general predictions.

Real-world application: avoid falling into the trap of thinking that we can precisely forecast what will happen. This is particularly true for economic forecasts, which are subject to changes that are not only probable, but certain and impossible to predict. More general predictions can be useful, but they should always focus on long-term underlying patterns. If in doubt, resort to the trusty calculator which does only the most basic of operations, avoiding the temptation to get sucked into excessive complexity.

This is not an exhaustive list of ideas and applications, but it covers some of the most useful ones from an investment perspective. Overall, there is no direct or close link between cause and effect, but rather a combination of concepts which enable us to disentangle this path with more confidence.

CONCLUSION: SUBJECTIVISM AND OBJECTIVE PRICE

It might seem like a contradiction to be continually talking about the subjectivist methodology applied by Austrian economists – which puts mankind's activity at the centre and where nothing is objective, due to man's continually changing activity – while at the same time discussing my ‘objective/target’ price for the companies I invest in based on my valuations.

In reality, what we are doing when we invest is trying to predict the direction entrepreneurs (understood in the widest sense to include all of us) will take in the future, thereby bringing about a change in current subjective valuations. We are interested in discovering the future ‘objective’ value, which is no more than the sum of countless subjective valuations made by these entrepreneurs. It is a purely entrepreneurial endeavour: attempting to predict where a new market need will arise, who could meet it, and at what cost. Once this has been estimated, the aim is to see whether securities markets will allow us to capitalise on incorrect price formation resulting from entrepreneurial errors by other agents. Once again, it is a purely entrepreneurial endeavour.

In conclusion, my experience is that the long-term outlook that all investors should adopt is perfectly complemented by the Austrian School of economics, with its sound logical framework and similar long-term perspective. Understanding the general functioning of economic institutions serves as a compass which gives us knowledge, providing us with the necessary peace of mind to be able to navigate troubled waters without fearing that we will run aground.