CHAPTER 5

Investment

Now that we have a conceptual economic framework to employ, we can turn specifically to investment. In doing so, the key point I want to highlight is the vital role of saving. Saving, unsurprisingly, is key to investment and the ultimate source of future wealth. Without savings, there can be no healthy investment or general well-being.

SAVING AND INVESTMENT

Each individual accumulates savings at a different rate, requiring a varying degree of sacrifice in terms of income that is not consumed. Saving finances technological development and wealth creation, and is responsible for the continual improvement in the standards of living that we enjoy today.

Although some misled people warn of a supposed one-off savings glut, an excess of savings is never bad news; it always contributes to financing projects which improve the productive structure. If an excess of savings results in very low returns and savings cannot be put to good use over a reasonable period of time, they will end up being consumed in products and services.

Personal propensity to save depends on a large number of factors: income, age, consumption or investment opportunities, concerns about the future or an inheritance… No two people have the same propensity to save, nor does this propensity remain stable over time.

In reality, saving, for a lot of people, is a – fortuitous – problem to be resolved. The key questions we ask ourselves are: What to do with them? How to preserve them? How to grow them? Will I be able to retire?

It is surprising how little time we spend addressing these questions. When we buy a house we spend months researching and weighing up the pros and cons. This is logical; frequently it is the biggest investment decision of our lives. The same thing is true when we buy a car or decide where to go on holiday. We weigh up the different options, leaning towards one or another after an exhaustive analysis of the advantages and disadvantages.

However, when it comes to deciding whether it is advisable to buy Telefónica shares, or determining which mutual fund is most suitable for our savings, it is surprising that we take this decision in a matter of minutes. We often do so after listening to the somewhat self-interested advice of those around us, without receiving truly qualified guidance, and without dedicating the time to study and reflect on a decision of this magnitude.

As fund managers, we have earned the trust of thousands of clients. This is a meaningful figure – bearing in mind that we don't do any marketing – but it is also ridiculous. In Spain there are nearly 10 million shareholders in mutual funds. How is it possible that a product which has offered clients such clear value – a 15% annualised return over 20 years – is not more popular? I am not complaining, instead simply pointing out that it is surprising and particularly serious given that these days the Internet places all the necessary information at our fingertips.

Deciding how to invest our savings should always be a slow and deliberate process – assessing alternative options according to our individual needs and the characteristics of the alternatives. Like nearly everything in life, knowing ourselves is the first step to making the right decision, which does not necessarily involve going after the best possible return. Later on I will try to describe the problems associated with having a personality that is not well suited to investment, but for the time being I will focus on something less ambitious: providing a simple explanation of the different investment possibilities for our savings.

REAL OR MONETARY INVESTMENT

When looking at investment alternatives, I will avoid a typical description of the multitude of asset types. Instead, I will focus on simple classification to narrow things down and go straight to the heart of the problem: investment in real assets or investment in monetary assets. Strangely enough, I recently discovered that von Böhm-Bawerk distinguished between goods and promises, which comes down to real and monetary assets. I mainly consider shares as investment in real assets, although I also analyse other assets that are more easily replicable, or commodities.1

This classification between real and monetary assets is not that common, but it helps to significantly sharpen the investment landscape.

Investment in Real Assets

Real assets reflect ownership of underlying assets, albeit with greater or lesser immediacy. Such assets create income for the specific service they provide to society. This includes shares, real-estate properties (homes, hotels, offices, etc.), commodities (gold, oil, copper, etc.), art (in the broadest sense, including any type of collection), and, generally, any product or service which is valued and demanded by human beings: tables, chairs, income rights for a sports personality or artist, etc.

Real assets also encompass all the capabilities and qualities that we might develop ourselves: education, skills, relationships, etc.

The essential characteristics of real assets are: ‘ownership of the thing’, which can be direct or indirect (shares, for example, are representations of property), total or partial (we can own the whole asset or a minimal percentage); and ‘variability in the income generated by the assets’. The degree of income variability will depend, firstly, on society's interest in the product, which will change over time and will be immediately reflected in the price that society is prepared to pay for the good. And, secondly, the producer's capacity to offer the product at a reasonable cost, because not everyone is in a position to supply efficiently.

As the photos below show, real assets come in many shapes and forms, covering a very significant part of the assets owned by the majority of people. This is especially true for people on low incomes, who limit their savings to immediate material goods: houses, furniture, cars, etc.

The main upshot of owning an asset which fulfils a service demanded by society is that it will sustain its purchasing power reasonably well in any economic environment, so long as society retains an interest in it. Returns on real assets will vary according to numerous factors, but their ability to retain purchasing power reasonably well is irrefutable and crucial.

However, within the category of real assets it is worth quickly distinguishing between unique assets or assets with a distinct competitive advantage, and assets that are easily replicated or substituted. There is no clear cut-off between both types of assets; instead, there is a continuous line, with unique assets at one extreme with a very high capacity to generate exceptional income. Actions in listed companies protected by very high barriers to entry are an example: say, Coca-Cola in the twentieth century and Facebook in the twenty-first.

Examples of real assets are shopping centres, education, industrial plants, farms, houses, thermal power plants, and roads.

Commodities, especially gold, are at the other extreme. They are subject to technological improvements that have resulted in continuous reductions in mining costs and, accordingly, their price. However, in recent years, mining costs have become dearer as a result of sudden and spectacular growth in China. This has offset the impact of technological advances, but it is unlikely to be a long-lasting effect.

Different real assets – shares with less competitive advantages, real-estate assets, and other assets – are located along this line according to their relative quality.

Monetary Investment

Monetary investment grants the investor a promise to pay a fixed income in a specific currency. Normally this promise is backed up by income flows generated by the issuer, albeit with certain limitations.

In this case, the investor does not own the entity that has issued the payment promise, they only own a promise governed by a contract in a specified currency.

Bank deposits and debt issues by government and companies are examples of this type of investment.

It is true that non-payment in the case of private debt issues could allow the investor to have access to ownership as a last resort, thus recovering at least part of the investment. But the same is not true for public debt. In the words of the outstanding and oft-overlooked Harry Scherman: ‘This type of [public] promise does not represent, in most cases, any type of tangible wealth’. Public debt offers no type of guarantee, other than the word of the issuer. We will never be able to access the government's assets; they have more tanks than any investor. (Elliot Associates recently tried to recover part of their investment in Argentinian government bonds, going after some of the country's assets around the globe, such as the Argentinian navy training vessel. This search was not very successful, but the change of government resulted in an eventual agreement.)

However, the problem here is not so much obvious non-payment, which for private debt is protected by underlying assets, but a less obvious form of non-payment. Specifically, the loss of value of the promise to pay as a result of the loss in value of the currency in which the contract is denominated or referenced. This problem is less obvious and as such much more dangerous for the saver, because it can be hidden or supressed over many years behind a façade of apparent stability. As investors we receive interest each month or year without fluctuations or surprises, until one day the crisis can no longer be contained and it suddenly explodes.

Furthermore, all types of promises to pay, both private and public, can be affected – not just exceptional defaults.

In reality, the two types of assets described – real and monetary – are not comparable because they are different in nature. On the one side, we are talking about payment rights deriving from ownership of an asset which interests the public (real assets), while on the other we are talking about a promise to pay backed up by paper money (monetary assets).

The only reason that financial markets typically compare shares and bonds – the clearest embodiments of both asset types – is for ease. Appendix A at the end of this chapter explains how these ideas impact on the key concept of the discount rate.

WHICH TYPE OF ASSET IS MORE ATTRACTIVE, OFFERING HIGHER RETURNS OVER THE LONG RUN?

The key question is: Which type of asset is more attractive as a long-term investment? Which offers more returns? Which is less risky?

The response should begin with an upfront reasoning based on Austrian logic: the number one objective of any investor should be to maintain the purchasing power of their savings. This is a priority and a fundamental basic principle. The idea of gaining purchasing power is subsequent to at least sustaining the starting position.

Real assets fulfil this role, by definition they maintain purchasing power; we can adapt them to any economic environment. The relative attractiveness of these assets will depend on their quality, represented by their degree of distinctiveness. As we will see, the most attractive assets are listed shares (and unique talents).

By contrast, there is no room in a long-term perspective for investing in monetary assets held hostage to the currency in which they are denominated. As a result of the abandonment of the gold standard or any other type of similar currency anchor, currencies are subject to continual depreciation, induced by monetary inflation. The latter is a result of the issue of more paper money than would correspond to output growth (in reality, output does not need more money when it expands, any quantity of money is optimal to support output. We have already noted that the natural state for an economy is deflationary).

As such, a priori, it would appear that real assets provide a greater probability of maintaining the purchasing power of our savings.

On the basis of this a priori self-evident premise, the next step is to see whether it has been confirmed over time.

HISTORIC EVIDENCE

Despite the difficulties of comparing such different assets, we are going to look at historical evidence. We will then dive into the theoretical explanations for the results. As we underlined in Chapter 4, without a logical foundation, empirical analysis has no value.

The evidence can be found in a multitude of studies on the long-term returns of different assets. Listed shares and public debt are the assets that have received the most thorough analysis, but we can also investigate the performance of other real assets.

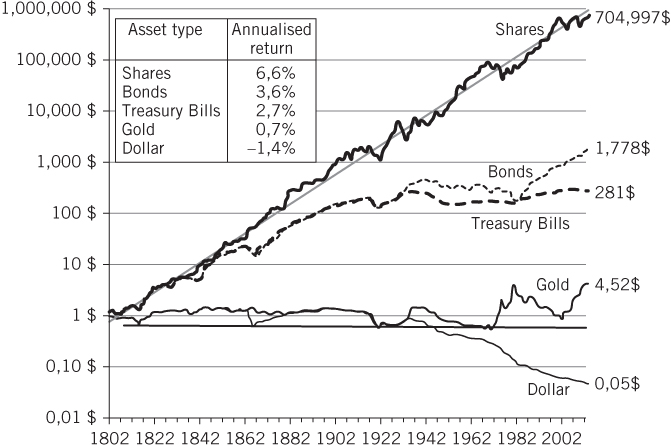

Starting with Jeremy Siegel's well-known study, American equities have obtained long-term real (after inflation) annual returns of 6.6%. Purchasing power has gone up by 6.6% every year. These are data for the last 200 years, and are surprisingly consistent over time. So much so that seen from this perspective, major crises – such as 1929 – look like small bumps on the road.

Source: Siegel (2014).

Economic growth is ultimately the basis for generating equity returns, since they mirror the behaviour of economies. In the long run, countries with sound and healthy structures, which save, invest, and do not excessively indebt themselves – in other words, countries where they do things right – grow, create employment, and have a strong financial system, enabling new projects to be taken on and providing liquidity to those who finance these projects with their savings. These ingredients create a developed capital market, which, over the long term, reflects the positive performance of the economy, allowing good returns to be obtained by not just initial investors in business projects, but also investors providing liquidity to these projects through share purchases of listed companies at a later stage in their development.

The global economy has grown by 3% each year over the last 100 years. This has been enough to allow for healthy and attractive capital markets for saving and investment. While some authors disagree, the increase in the value of long-term equities reflects a stable economic environment, which allows for this creation of real wealth.2

Other assets have performed much less strongly over time than equities: government bonds have obtained a return of 3.6%; Treasury bills, 2.7%; and gold, 0.7%. The abandonment of the gold standard and the subsequent increase in inflation have led to a decline in returns on fixed income over the last 80 years compared with the previous period, putting more recent returns below this 3.6%. Meanwhile, gold has performed better since the end of the 1960s, when the last currency anchor to the gold standard was removed.

Although a difference of 2–3% per year may seem small, over the long term the effect is astonishing. Just compare the differences in accumulated assets in each case: one dollar of shares in 1802 converts to 704,997 dollars in 2012, in real terms. In other words, purchasing power has increased 700,000 times! Meanwhile, this same dollar, invested in bonds, would have translated into 1,778 dollars. Certainly a reasonable return, but clearly less than what is on offer from equities.

Source: IMF WEO, 4/16. Stephen Roach, ‘A World Turned Inside Out’, Yale Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, 5/16.

A dollar of gold, typically used for refuge, would have converted into 4.52 dollars, barely maintaining its purchasing power, meanwhile leaving the dollar under the mattress would have led to a devastating loss of purchasing power, with paper money losing 95% of its value: that dollar would have converted into five cents of purchasing power.

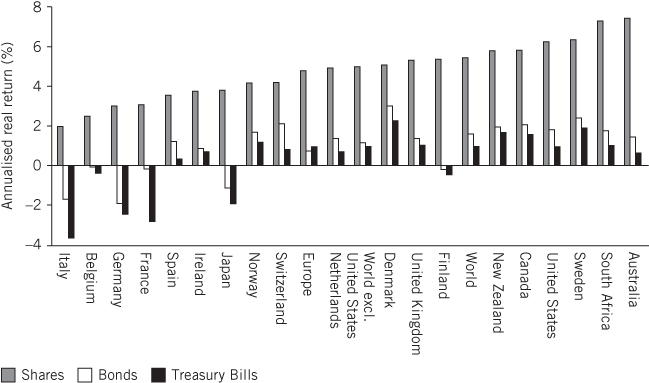

Equity outperformance has taken place in all the countries under study, as can be seen in the following chart:

Source: based on Dimson et al. (2011).

The analysis for other countries has been performed for a shorter period: 1900–2000, but with no less resounding results. All countries exhibit greater returns from equities compared with fixed income. Including countries that have gone through wars and calamitous financial situations, such as Germany and Japan. My own country, Spain, posts a real annual return of 3.6% for equities. Also a long way above fixed income.

This analysis used countries accounting for 89% of the market in 1990, meaning that the sample is very representative. Moreover, in countries registering lower equity returns – such as Germany, Italy, France, and Belgium – bonds performed even worse, with negative real returns.

Finally, in the worst-case scenario, such as a Soviet-style revolutionary confiscation of assets, the investment is a lost cause regardless of the asset. Therefore, there is no greater risk associated with equities.

In conclusion, despite the difficulties involved in forecasting, we can calmly assert that over the long term, owning a diversified portfolio of shares will produce a greater return and a larger increase in the purchasing power of our savings than any other alternative investment, especially in comparison with monetary assets. Later on we will develop a logical explanation for this, which will tie in with the explanation related to economic growth.

We can also confirm that other real assets have performed more poorly than equities. We have seen what happened with gold, and if we analyse other assets such as real estate (see Appendix B at the end of this chapter), oil or metals, we will find that they maintain their purchasing power, but fall a long way short of the return on equities.

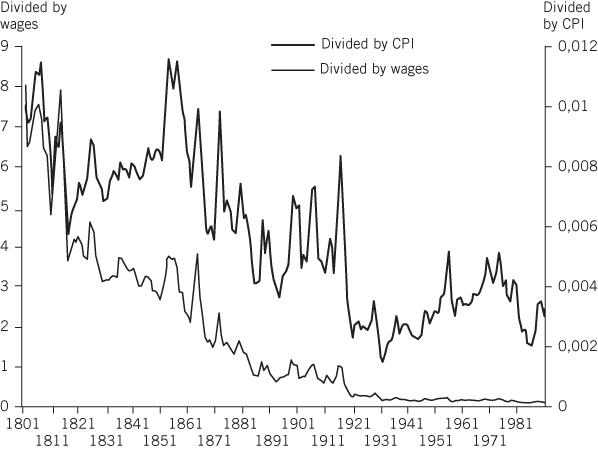

Source: Simon (1998).

This is because these assets are easily replicated or substituted. The increase in productivity from technological developments and better management methods systematically lowers production costs and, as a consequence, thanks to competition, consumer prices. This is why they are barely able to maintain their purchasing power: each year they have to fight against a 1% or 2% price reduction due to improvements in production.

Source: Simon (1998).

These ‘other’ real assets can endure long periods of lower returns than monetary assets, but they have a notable advantage over the latter: their defensive character. Not all investors attach the same importance to peace of mind, but I think it is essential. Maintaining the purchasing power of savings during times of high drama is crucial for an investor. That is why I am willing to sacrifice some return in exchange for the certainty of sustaining long-term purchasing power. We will also see a little later why real assets defend themselves better in these dramatic moments.

VOLATILITY (NOT RISK)

Curiously, the positive difference in return from equities is known as a ‘risk premium’. Implicit in this language is the idea that greater return implies taking on more risk. As we will see, this could not be further from the truth.

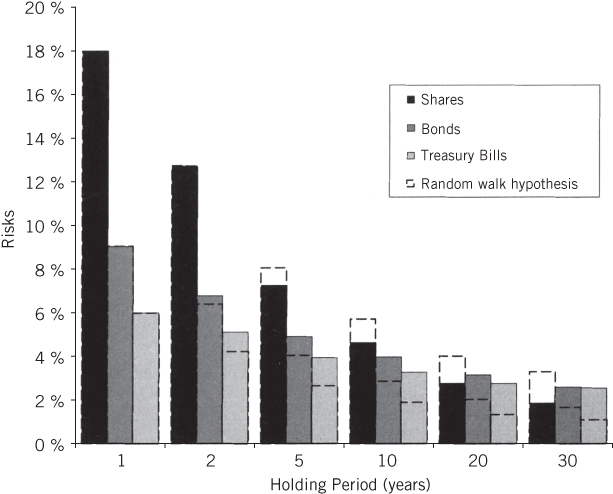

Equities are subject to greater short-term volatility, but not over the long term. The longer the timeframe we analyse, the more this volatility progressively diminishes.

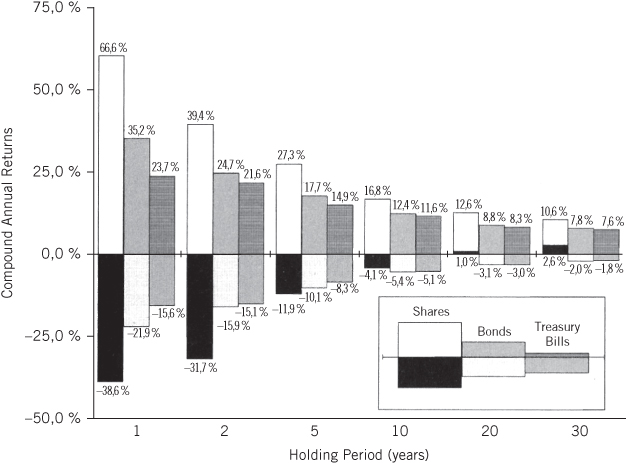

In the chart below we can see that for periods of up to five years, the maximum positive return on equities is the highest among all assets, but so too are the losses. This fits with our vision of the variability of shares. But this is no longer the case for periods of 10 years: the worst 10-year period for an equity investor saw an annual real loss of 4.1%, compared with 5.4% for bonds.

Source: Siegel (2014).

The better performance of equities becomes even more accentuated over longer periods: there is no period over a 20-year tenure where equities lose purchasing power; the worst period saw a return of 1% above inflation. The same thing happens over 30 years: the worst period generated a real return of 2.6%. By contrast, the worst 20- and 30-year periods for bonds are very negative.

If we employ the usual calculation of volatility as the standard deviation of returns, we obtain similar results, as would be expected.

From all this we reach the surprising conclusion that for all long-term investors, equities not only offer greater returns, but do so taking on less volatility. This might not appear intuitive to the reader, which is why it is necessary to analyse the rationale in a degree of detail.

Source: Siegel (2015).

WHAT IS RISK?

Before we get started, it is worth clarifying that volatility is not the best measure of risk. The risk of an investment is the possibility of a permanent loss of purchasing power as the result of making an error of judgement.

We have seen that the possibility of this happening in a diversified long-term portfolio of equities is very limited. Investing in an index or in an index fund, we can reduce the possible errors involved in the specific selection of stocks.

Volatility measures the intensity of changes in asset prices, which may or may not be related to what is going on with the underlying asset. In fact, volatility is the long-term investor's best friend, enabling them to find opportunities that would not otherwise have existed. Greater short-term volatility means that more investment opportunities will arise and increased long-term returns with less risk. For example, if the market collapses and equities fall by 50%, we will be buying cheaper assets and taking on less risk. The underlying rationale is that the fall is not justified by good reasons (and there is mean reversion), but is instead a consequence of erratic human behaviour, something that we will turn to later.

By contrast, with monetary assets this risk, or the potential for a permanent loss of purchasing power, is very real and could be very significant. This has been the case on countless occasions over the course of history, where we have seen continual state defaults and currency depreciations. In some cases, losses have reached 100%, such as in Germany in 1921–1923.

As we have pointed out, when an investment in equities has been completely wiped out due to a revolution or a similarly dramatic situation, the same has happened to investments in monetary assets. In other words, in the worst case we are equally badly protected with both types of assets.

WHY DO EQUITIES OFFER BOTH GREATER RETURNS AND LESS LONG-TERM RISK?

This surprising result, which contrasts with what we read daily in the economic press and the typical recommendations of financial advisors, has a relatively simple explanation if we consider the basic nature of the two types of assets.

In real assets, and specifically in shares, we are co-owners of assets which are overseen by other owners, who normally – though we cannot say always, because on occasions corporate governance is not up to scratch – take the same long-term perspective, which is key to the company's future success. The environment is important, and if there is an economic or financial crisis which depreciates the currency, the company will be affected. However, the capacity to adapt and the company's long-term vision will enable it to continue with the business under new circumstances, dealing with currency or legislative changes: it will switch to selling its products in reals, pesos, or drachma, or at a higher price if there is hyperinflation, but ultimately if the product is good and people need it, the company will continue selling it under the new circumstances and will continue generating surpluses in the form of profit.

The cause of this currency depreciation is the increase in the amount of money in circulation, which also leads to an increase in the price of assets in this reference currency. These are two sides of the same coin: inflation and currency depreciation. When an asset which offers a service to society – an office, a house, a sausage, or a mobile phone factory – faces an inflationary situation, the company will adjust the price of its products and the remuneration of the factors of production in line with the new state of play. If prices increase by 5%, it will increase its prices and costs by 5% and therefore the relative situation does not change. If prices increase by 50%, the same thing will happen, and equally if they increase by 1,000% per day. Obviously, these would be far from ideal operating conditions, but the company can adapt and at least survive. Accordingly, the owners will also maintain their relative position and even improve relative to holders of fixed-income assets, whose prices cannot adapt to the new situation.

Taking a stake in an asset though shares or, in other words, being a co-owner of a company which produces a tangible, concrete, and real good – which is valued and demanded by other economic agents – is what enables us to protect ourselves against the main investment risk: the depreciation of the currency in which it is denominated.

By contrast, when holding monetary assets we depend entirely on the value of the currency, which is always subject to political vicissitudes. There are both time preference and principal–agent problems. While as investors we are thinking in the long term, in the future, politicians think about ‘their future’, a future which is almost always too short and bracketed by the next elections. With re-election at the forefront of their minds, politicians will tend to delay necessary but difficult and impossible decisions for as long as possible, leading to an accumulation of unresolved problems, which sooner or later will lead to structural imbalances, loss of confidence in the economy, and inflationary depreciation of the currency. For us, this means the immediate loss of value of our monetary investment.

The principal–agent problem arises due to the misalignment of interests between investors in monetary assets and politicians and/or their advisors or intellectual inspirers. The latter can make errors, due to the always unforeseeable consequences of their actions, but these errors tend only to emerge in the medium and long run, meaning they do not suffer a significant risk in the short term. Later on they will try to explain them away by ‘unforeseen’ external factors or due to previous poor decision-making, but the error will remain.

There are some monetary assets with defence mechanisms against currency depreciation, such as inflation-linked bonds. But at times of high inflation the government in question will repudiate this type of debt precisely because it is the most onerous of them all. A government in crisis will not pay interest rates of 30% if inflation were to be close to these levels.

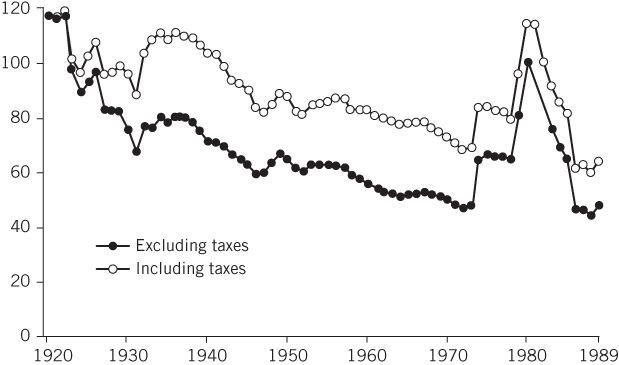

To conclude, an alternative way to visualise this can be seen in Jeremy Siegel's charts, set out on the following page. These charts show that during short periods (a year, for example), equities are the best asset, despite having a lower return in high-inflation periods; over longer periods (30 years), equities perform steadily and very positively, close to their average historical return. The same is not true for Treasury bonds and bills, which suffer enormously under high inflation.

Consider an example: we are offered the choice between a stake in the future earnings of Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi. Let's say 10% of their future earnings over the next 10 years (assume the offer arrives when both are at the peak of their careers) or a bond issued by them payable over 10 years in euros. We will not dwell on analysing the potential return on both offers – this will depend on the future of the players. However, the option linked to earnings will face greater volatility – as there could be injuries or game changes – but it will typically offer a greater return.

The problem with the bond is that it faces an additional risk of currency depreciation. Imagine that there is a financial crisis and the reference currency loses value. Either our players change teams or currency. They will do whatever it takes to continue maximising their capacity to generate earnings in this new economic context: they will earn in dollars or yuan, or they will go to the Japanese league; they will adapt. And we will continue receiving our 10%, albeit with some changes in purchasing power, in one sense or another, depending on whether football becomes more or less appealing to society during the crisis.

Source: Siegel (2014).

Meanwhile, investors holding Ronaldo or Messi bonds, which for a while have lived comfortably with the apparent lesser volatility of their bond, when faced with the shock, will now receive payment in a euro which is of less value. They will have suffered a loss of purchasing power in the same proportion as the depreciation of the currency (less what they have earned in interest).

In general, in these extreme situations the impact passed on to the bond through loss of currency value exceeds what the owner of a share might lose in profits from not having completely adjusted to the new circumstances. Such extreme situations come unannounced, but they always put in an appearance. Therefore, provided that we are willing to accept more short-term volatility, as shareholders with a stake in profits we will be avoiding future financial disasters that sooner or later will take place, and which dramatically affect monetary assets.

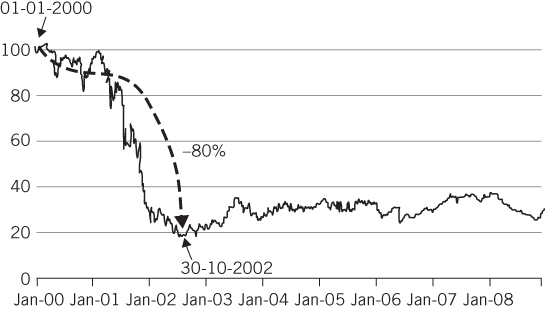

Argentina

Speaking of Lionel Messi, let's also talk about Argentina, a country which was the seventh global power at the start of the twentieth century. In 2000, after various years of pegging its currency to the American dollar, economic imbalances resulted in the umpteenth suspension of payments by the country and the imposition of the so-called ‘corralito’, preventing dollar deposits from being taken out of bank accounts. The peso–dollar exchange rate, which had been maintained until then at one, immediately fell by half, meaning two pesos were needed to buy a dollar.

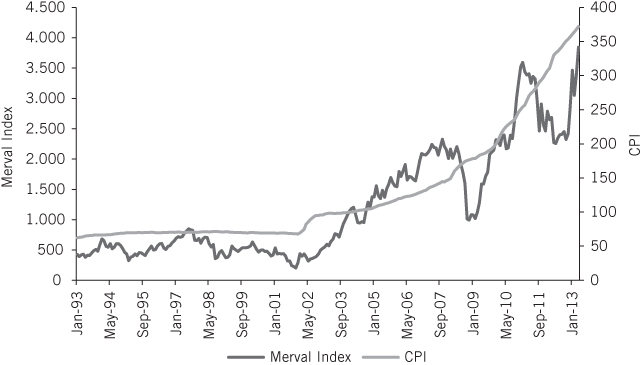

Source: Guerra (2012), based on BCBA, INDEC, and IPEC-Santa Fe databases.

This was a really extreme and dramatic predicament, which led to falls in the price of public debt and shares. But it didn't last long. A few months after the payments suspension, equities embarked on a meteoric rise, enabling investors to recover the losses inflicted by the currency depreciation.

As can be seen, the adjustment of equities to inflation is almost perfect. However, the public debt story is very different.

Today, over 15 years later, Argentinian public debt has lost 70% of its value, while the Merval, the Argentinian stock exchange, has multiplied in value by 20 – compensating the loss in value of the Argentinian peso, which is now at 1/15 against the dollar.

Source: Bloomberg.

Argentina is just one of countless examples that have taken place over the course of history, but the mechanism is similar in nearly all of them. For example, on 20 June 2016, in the Financial Times, there were two news items on two countries, Venezuela and Egypt, where one can see the problem evolving practically in real time. In 2016, according to the IMF, inflation in Venezuela reached 480% per annum and in Egypt a flood of house purchases are being made in the face of generalised distrust in the country's leaders.

It is clear that in less developed countries, where distrust of governments is much higher, the attraction of real assets has always been clear to savers.

MORE ON THE POLITICAL PROBLEM

We have seen how the problem with fixed income is inflation, which destroys the purchasing power of money. Why is there inflation? We will follow Murray N. Rothbard, who addresses this question in his book What Has Government Done To Our Money?3 I have already spoken of this brief but outstanding account of the origin and evolution of money, and how government intervention impacts on this evolution: ‘If government can find ways to engage in counterfeiting – the creation of new money out of thin air – it can quickly produce its own money without taking the trouble to sell services or mine gold. It can then appropriate resources slyly and almost unnoticed, without rousing the hostility touched off by taxation’.

Purchasing power is destroyed by currency depreciation, which – to re-emphasise – is a result of the increase in the money supply in circulation. It is a problem of supply and demand: the more money there is in circulation, the less value it has in relation to other goods. And why increase the money in circulation?

This is where the political class comes into play. After having exhausted the possibilities of increasing taxes, given that there is always a limit that the public is unwilling to cross, and after having also reached a limit on public debt issue, investors too run out of patience (‘The limit is the point at which promises to pay stop being credible’) – the political class then has to find other funding mechanisms. And the most suitable mechanism for their interests is to issue paper money – especially after the abolition of the gold standard, which supported currency issue with something tangible, robust, and real – currently under the control of the central banks, administered by the political class.

Little by little, the springs that forestalled currency depreciation have been dismantled, ending up with today's current paper money, which is useless at holding its value over the long term.

In addition to the significant depreciation problem, there is another serious issue: the new paper money in circulation is not neutral. To begin with, it favours those who are closest to the government, who will be up to speed with looming political manoeuvring. It also complicates future decisions, since it creates an instability that was prophesied by Lenin in his famous words: ‘The simplest way to exterminate the very spirit of capitalism is therefore to flood the country with notes of a high face-value without financial guarantees of any sort’.4 But what is more, it impoverishes the saver who lends and invests, and improves the situation of the debtor, which is frequently the state. This explains the natural and remorseless tendency of governments to depreciate currencies via inflation.

In fact, as Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff have explained,5 nearly all states at one time or another have reneged on their promises to pay (be it via currency debasement, default, or issue of more paper).

As it happens, Spain, during its golden Imperial Age in the sixteenth century, when it was the great economic power of its time, suspended payments six times. One of the direst cases, as we have already highlighted, was Germany during the 1920s, but we could list dozens of similar situations. Once again, the elimination of the gold standard has facilitated a system of monetary inflation as a form of non-payment.

But why do states do these things? Firstly, they do them because they can. A large number of states have been created through violence, and all have a monopoly on force. This combines with two previously mentioned factors which are inherent to the state: the principal–agent or representation problem, derived from the logic of political action, and the time preference problem, resulting from electoral cycles.

Source: Reinhart and Rogoff (2011).

The political class which controls the state structure has different interests from investors. Marcus Olson6 explains that the best-organised groups ensure that political power moves in the direction they intend. Well-organised business organisations, civil servant groups, and workers in trade unions achieve their objectives more quickly and effectively than companies that are unattached to lobbies, or isolated workers, or unemployed people.

Logically, these groups are led by people motivated by very human incentives (the public choice school has explained this extensively). Like all of us, these people have their interests, objectives, careers, tactics, jealousies, plans, etc. We are talking about individuals who do not normally expose their own capital and, therefore, do not take risks in their decisions. If they are right, they will take responsibility for them and if not, they will disown them, but everyone will give their own account of what has happened and propose additional measures to correct the problem.

As Hans Herman Hoppe illustrates,7 the time preference problem derives from electoral cycles, which prevent long-term decisions – with limited electoral visibility – from being taken. What politician will confront elections promising public austerity? It is not common, although there are some honourable exceptions in advanced and mature societies like Germany where this is almost always the case and, more recently, in the United Kingdom.

The question is: How to put aside money in good times for leaner periods? This is what any sensible head of household does. By contrast, for political leaders wanting to continue governing, it will almost never be the best approach, because 30–40% of voters who grant them the capacity to govern (usually representing around 25% of the population) will call the shots. Within this decisive group, the best organised will shepherd the rest.

I am not talking about replacing democracy with other forms of governance, even though major countries such as China have managed to deliver extraordinary improvements in living standards with a non-democratic regime. Instead, the goal is to highlight the flaws in order to make progress. Either way, as von Mises used to say, democracy will always be the best way to get rid of inept leaders.

However, there is no need to be overly reverent to democracy either, as happens when certain people speak of the tyranny of markets over the democratic majority. There is no better expression of popular will than people's actions in daily life: decisions on work, buying and selling, leisure, health, etc. These decisions involve a lot of time and effort, something we cannot be sure applies when it comes to casting their vote in elections. Ultimately, the only people who really weigh up their votes are those who have a high degree of civic awareness and few prejudices, something difficult to marry up.

Surprisingly, some people think the opposite: they consider the person who votes every time to be extremely sensible and knowledgeable, but – somehow – in the periods between elections they seem to think this same person becomes a useless being who has to be helped to make decisions on the products and services they should buy. This distorted vision of reality usually originates with interested parties (politicians prone to intervention and ‘intellectuals’ with little audience), since it is clear that the tyranny of the market is all of us taking much more considered decisions than how we decide to vote.

Finally, financial markets move for infinite reasons: economic developments, political decisions, unexpected shocks, technological innovations, etc. All of them have different impacts and we cannot and should not seek to analyse them in depth, due to the difficulty of establishing appropriate relations between cause and effect. We have focused on the heart of the matter. The – to some degree measurable – impact of some decisions, mainly political, on the two main types of assets. We measure this impact through currency depreciation, which has a very serious effect on one of these assets: monetary assets.

CONCLUSION

The conclusion of this chapter is that both logical and empirical results lead us to the same outcome. We should invest our savings with people who have a similar perspective and time horizon to us. This is the only sensible thing to do. And as the optimal thing for investment is always to take a long-term outlook or horizon, which is the only perspective that allows us to make minimal predictions, we should steer clear of monetary assets influenced by a political class that has an unavoidably short-term point of view.

We should therefore invest in real assets, particularly equities, which fulfil the specific needs of the population and are managed by people or business leaders with a long-term perspective and optimal capacity to adjust to changes in the environment. (Later on we will see that it is essential that they be people or business leaders in the most radical sense: entrepreneurs. It is surprising to see how executives are often confused with business leaders or entrepreneurs, which reaches the point of absurdity when awards such as ‘Entrepreneur of the Year’ are given to executives.)

In addition to equities, other real assets will also protect us against currency depreciation processes, which tend to be more frequent since the disappearance of the gold standard. However, as they are easily replicable, these assets do not reach the same level of return as equities. Some investors with an ‘Austrian’ background lean towards gold or treasury at times of political uncertainty or excessive currency manipulation, as occurred in 2016. It is worth reiterating that there is no sense in maintaining liquidity in an asset (treasury) subject to a brutal loss of value, precisely as a result of this currency manipulation. It is patently incoherent and can only be forgiven if this treasury is supported by gold or another reliable reserve.

Neither is the argument convincing that some monetary assets offer liquidity. This function can be perfectly met by other real assets, such as some well-capitalised equities at reasonable prices. We can always find shares with these characteristics, and the excuse that their prices will fall in a crisis holds no water, given that, firstly, these crises are always temporary and our horizon should be long term, and secondly, we should invest resources that are not immediately needed.

Investing in gold is more coherent, but time has shown that equities – property deeds for companies that produce real goods and services demanded by society – perform exceptionally over the long term, with returns that are substantially better than other assets, taking on less long-term volatility and less short- and long-term risk.

The conclusion is unequivocal: the bulk of our savings should be invested long term and in equities. We only need hold positions in monetary assets to cover occasional cash needs.8

APPENDIX A

Discount Rate

As a direct consequence of the subjective nature of our investment alternatives and the practical impossibility of recommending investment in monetary assets, it is worth clarifying and setting out my approach to an essential concept in the investment world: discount rates.9

The discount rate is the rate at which possible investments have to be discounted. It reflects the notion that it is not the same thing to receive income from our investments, or the principal itself, in year one as opposed to year five. Another way of thinking about it is as the opportunity cost. Investing in one thing means not investing in another, and discounting is effectively comparing one with the other.

In standard financial practice these flows of money are discounted at the risk-free rate plus a risk premium.

The risk-free rate is normally the interest rate on the bond issued by the government where the investment is taking place, which historically varies between 2% and 10%: a wide range, which reflects the historic strength of the government issuer and, particularly, its repayment capacity in a non-depreciated currency in which the debt is issued.

The risk premium, as indicated by its name, is the additional premium required of an asset to invest in it. The incorrect assumption here is that the asset is more risky than the government bond. Historically, this premium has stood at around 3%.

CAPM theorists (in Chapter 6 we will engage in a more detailed discussion of the Capital Asset Pricing Model) incorrectly believe that the risk premium is a market parameter, instead of being personal to each investor. They therefore think that this premium can be calculated.

Finally, this risk premium is weighted by the volatility of the share price in the market: Beta. The market has a Beta of one. Less volatile shares have a Beta of less than one, while more volatile stocks are above one.

i is therefore the rate at which income flows are discounted.

This is standard practice, but I don't see any logic to it. Personally, I never use this discount rate and in the professional world I have only resorted to it on very rare occasions when the market pricing of ‘risk’ assets is very high. Even if we were to assume it made sense to equate risk and volatility – despite this being illogical, as we have already discussed – each investor has their own disposition towards assumable risk. ‘Market risk’ does not exist.

Just as when we analyse a company's future profits and all investors have a different opinion, it seems logical that each investor will discount at their preferred rate, using the ‘risk premium’ and Beta they consider appropriate. In Chapter 6 we will critique the CAPM more extensively.

Therefore, as investors, each of us should discount according to our preferences and alternatives, and after reading this chapter we now know that we should only invest in real assets and our alternative is other real assets. As we have seen, there is empirical evidence that investment in equities offers greater returns and involves taking on less risk than fixed income, especially since currencies are no longer backed by the gold standard. In situations of serious crisis there is a natural tendency for the currency to lose value; it is the easiest way out for a political class facing elections. And in this situation the crucial advantage of real assets is their capacity to adapt to a currency depreciation, or even new currencies.

Equities are a mere reflection of this ownership, making them an optimal way to protect against inflation in moments of serious monetary crisis.

The Discount Rate: My Own Version

Since real – supposedly risky – assets are the best way to preserve our purchasing power, and given that non-real assets are an unacceptable alternative, how do I discount my investment in assets?

I reiterate: with other real assets.

ia representing the return on my real investment alternative.

As a matter of fact, my best alternative investment has always been the funds I have directly managed, initially by myself and later on as part of a team. This is obvious, but worth highlighting as it is not that common in the financial market. If I devote myself to investing money and I have a diversified portfolio of good assets, how could this not be my best alternative? How could I ask potential clients to invest with me if it wasn't the case?

I have to compare any possible alternative investment – whether they be, for example, new business projects (generally friends and acquaintances), gold, or houses – with my preferred alternative: my funds. So far I have not had any doubt, which is why I have nearly all my family assets invested in them.

Ultimately, it is about discounting or comparing any investment option with the best possible alternative. And, for me, my best alternative is investing in the funds I manage. If I expect to obtain a return of 8% with my fund, I would not consider investing in any project where I don't expect at least an 8–10% return, assuming the same level of security.

Furthermore, the fund has an additional advantage: it does not require extra attention, it doesn't need time. This element must be included in the required additional return. It is obviously a very personal decision. A property or investment project is highly time-consuming, and we should demand an extra return from them precisely for this reason.

If I didn't manage funds, my second best alternative would be fundamental mutual funds (semi-passives: we will discuss these in more detail in Chapter 6), or equity funds managed by people I trust. Finally, I would consider other types of real assets: real estate, commodities, or entrepreneurial projects. But these are less attractive to me, either because they are very replicable assets, lacking the ability to set their own price (real estate and commodities), or they are actually very risky (entrepreneurial projects).

I have spoken about what applies for me, but this approach should be adapted to an investor's personal situation. Typically, the average investor (who has not read this or Jeremy Siegel's book) is more comfortable investing in property. Intuitively it is easier to wrap your head around. So any possible investment should be compared with – or discounted against – the investor's best alternative, which might well be a particular property. Only if they find a better alternative, such as a good fund manager, passive index, stock, entrepreneurial project, etc. should they take money out of their base investment.

On a professional level, the attitude is much the same when deciding between different stocks. The decision to invest in a particular stock should be discounted or compared with investing in other stocks.

And not with fixed income. Only in very specific situations can this stance be softened and a degree of flexibility introduced. There are some motives for occasional flexibility.

One could be because other market actors don't have such a radical outlook and this means that at points in time, when equities are expensive, it makes sense to temporarily hold more liquidity. The market normally prices between a P/E ratio of 10 and 20, with a historical average of 15. If the market is pricing at a P/E of close to 20, it is worth having liquidity. It is difficult to sustain a P/E of 20 or above for a very long period of time, because the biggest factor weighing down equities starts to come into play: the impact of price volatility on the perception of assets. This means that investors have tended not to be willing to pay above a P/E of 15 for prolonged periods of time.

This is an empirical reality, but not necessarily logical. Some day this perception might change and the historic average could increase to 20, at this point the long-term return on equity and fixed-income assets would be brought practically into line.

The second, more practical reason, is the added flexibility very liquid assets provide for managing redemptions or the emergence of sudden investment alternatives. This is less important because – as previously mentioned – this can be resolved by having a portfolio of large, liquid stocks which fulfil the same function.

In sum, we should discount using our best alternative. For me this alternative will never be a monetary asset based on paper money, but rather the mutual fund that I manage.

APPENDIX B

How to Invest Over a Lifetime

Circumstances change over time and it does not make sense to apply the same rules to differing personal situations. At some points we are not willing to accept volatility, while at other times losses are more tolerable. Across the OECD as a whole the majority of savings are invested in the real estate sector, 74%, while investment in equities and funds is minute, less than five percent. We have already seen that this distribution does not have much long-term economic rationale, while acknowledging the emotional logic. I am going to propose an alternative investment over time. Composition of Net Wealth in Spain (OECD)

| SPAIN | OECD | USA | |

| Non-financial assets | 80.7% | 74.1% | 48.5% |

| Primary residence | 53.9% | 51.2% | 31.5% |

| Other real-estate property | 23.7% | 17.4% | 12.8% |

| Vehicles | 2.6% | 3.2% | 3.4% |

| Other non-financial assets | 0.4% | 4.5% | 0.8% |

| Financial assets | 19.3% | 25.9% | 51.5% |

| Deposits | 5.3% | 7.6% | 7.0% |

| Bonds and other fixed-income securities | 0.2% | 0.9% | 2.0% |

| Mutual funds | 0.8% | 2.0% | 7.6% |

| Net equity in unincorporated partnerships | 9.0% | 6.7% | 4.5% |

| Shares | 0.9% | 2.3% | 5.7% |

| Unlisted shares and other own funds | 0.8% | 2.1% | 14.2% |

| Other financial assets distinct from pension funds | 0.7% | 0.9% | 1.1% |

| Life insurance and individual and voluntary pensions | 1.6% | 4.2% | 9.4% |

| Liabilities | 10.1% | 14.1% | 18.7% |

| Loans – primary residence | 6.1% | 8.4% | 13.0% |

| Other real-estate loans | 2.6% | 2.0% | 2.9% |

| Other loans | 1.4% | 2.4% | 2.8% |

Source: Moncada and Rallo (2016).

First Steps

One's main asset is in fact oneself. Our priority should be to improve our skills and become an attractive proposition to those around us. This normally implies a monetary sacrifice or time investment, which is possibly the most rewarding of them all.

Once we have exhausted our opportunities for prsonal development, we can consider how to approach the investor process.

When we are young, students or workers, we should start by investing all of our meagre savings in shares, or mutual funds which invest in equities.10

At this stage in life we can afford to take on greater volatility, making it logical to try to obtain the best return possible and try to start constructing a small amount of capital. If we suffer losses, there will be time to recover them.

Peter Lynch said that our first investment should be a house, our home, and this can make a lot of sense if we form a family – with all the responsibilities that entails. But if this takes some time to happen, as is the case these days in nearly all developed societies, equities are a more attractive initial proposition.

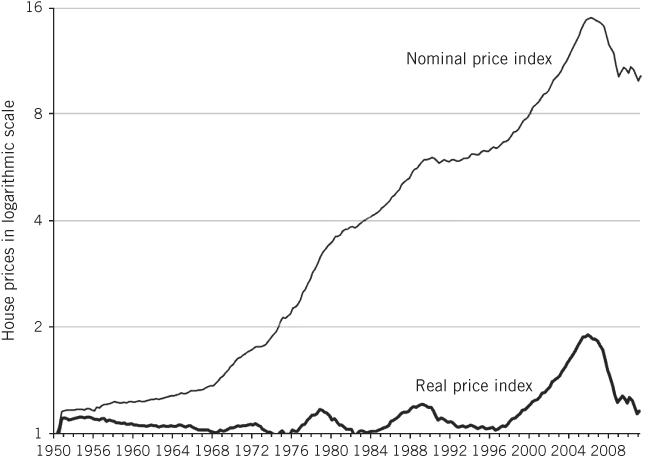

The real-estate sector is very much entrenched in our lives; until recently we didn't know about other forms of investment. Our forefathers did not have access to the infinite possibilities currently on offer, and they felt secure with their own property. But houses – as can be seen in the next chart – sustain little more than the purchasing power of our savings. The well-known market and real-estate analyst, Robert Shiller, presents similar results.

Source: Siegel (2015).

It is worth remembering that houses are a commodity. They are easily replicable goods, which tend not to age well. We have remarked on how technological development enables productivity to increase by 1–2% each year, meaning that the price of materials and production tends to decline in real terms by the same amount.

Obviously, this is not true for the other major component in the sector: land. But the planet, excluding some special spots such as Monaco or Hong Kong, currently provides us with all the land necessary to multiply the number of global inhabitants. In any case, this multiplication is not going to happen; population growth is set to decline dramatically by the middle of the century. As such, it seems unlikely that the value of land will experience major growth either.

However, the decline in prices is partially offset by the fact that with increased wealth, we are demanding better building materials.

In addition to being an easily replicable commodity with limited real increases in value, there are also maintenance costs to consider, which we know can be very high; transactions costs, which vary by country but are far from negligible; and management costs, which can become very uncomfortable or expensive for the owner.

There are some specific exceptions in the centre of large cities, due to space restrictions. But these are also replicable over time, and their overall performance cannot change all that much from the rest of the real-estate sector. Even a city centre can change with time. For example, in Madrid the centre of gravity has shifted northward, with a consequent loss in value of certain buildings in the old ‘centre’.

We can conclude that houses are like gold: they avoid the worst, but add little compared with equities.

Either way, the major problem at this point in life is having the capacity to save – either because of a paltry income or a lack of self-control over consumption.

Stabilisation

When we settle down, and create a family, two things can happen.

(1) We do not have any savings available. In which case – despite what we have already said – buying a house is the number one option, because a monthly mortgage payment forces us to save. Somebody who does not have any savings when they form a family, after several years of working, needs moral support to save and the obligation to pay back a loan serves this purpose. It is not the most optimal investment, but it compensates personality traits or the simple lack of resources which prevents us from doing the right thing: investing in shares. A mortgage mitigates the tendency to spend and not save, and makes up for a possible aversion to the visible volatility of equities, despite their great attraction.

Furthermore, some young people can't save because their salaries are very low, or because they have taken on debt to pay for their studies. In the case of the latter, after paying down the debt, if they have the capacity to save they should invest in shares, since they might have the right personality for it.

(2) We have now accumulated a small amount of capital. The choice is then between buying a house or renting. If the right course has been followed, we will have invested in equities for some years and have acquired some experience and confidence. The most natural thing would be to continue down this path, renting a property until we have sufficient assets in shares and it becomes potentially interesting to start diversifying.

It might be the case that our partner is more adverse to volatility and is not as comfortable investing in shares. This would be the time to think about buying a house. The decision should be based on the relative valuation of the two things at the specific point in time (sometimes one market is clearly more attractive than another) and one's individual degree of aversion to volatility.

Normally, the stock market pre-empts the real-estate market, meaning that it is common to be able to buy a house by selling shares. In my case, I always invested in shares up until 1998, when we bought our house. Equities had performed exceptionally in the previous years, and the price of houses had remained very static over five years, making it an optimal time in relative terms. Either way, shares have the presumption of innocence; only in very specific moments is it better to invest in houses. Equities are the right path most of the time.

Volatility is a problem that should not concern the reader of this book. I think I have made clear the enormous opportunity cost involved with monetary assets or relatively undistinctive real assets, such as houses, so my recommendation is to dive into the explanations set out here and try to overcome any aversion to volatility. It may help to review the reference list included in this and other books.

Maturity

Life goes on and it may become harder to save. General advice from this point on becomes less useful, as personal circumstances dominate. As a general concept, if money is not required for something specific or in the short term, equities remain the main option.

With the passage of time, and as we close in on retirement, we can think about holding more liquidity to cover expenses over the next two or three years. But this will depend on the total capital available and our aversion to volatility. If our accumulated capital is significant, this liquidity is unnecessary; even a significant market crash will not change our way of life. If it is not very elevated, it is worth having a part of our savings in fixed income to reduce the short-term volatility of income flows needed in daily life.

We always refer to volatility rather than risk, because as we know they are not the same thing. When we invest in equities we take on more short-term volatility but less risk over all time horizons.

If we follow this simple advice, we will have a comfortable retirement with reasonable savings and, above all, the habit of stoically accepting market movements, even taking an interest, knowing that we can take advantage of them.

Order of Preference

I conclude with a list of the order of preference of the different generic assets.

- Listed shares (in Chapter 6 we will distinguish between different equity funds and equities themselves). The advantage over non-listed equities is that they are more susceptible to aberrations resulting from panic and euphoria. When somebody sells their company on the private market they are fully aware of its future potential. The same is not true for public stock, where investors are either unwilling to stray from the pack or lack sufficient knowledge.11 Enduring movements derived from these aberrations will enable us to capitalise more from listed stocks.

- Other real assets. The choice should be made between them according to each asset's current position in the cycle and our knowledge and experience of each of them. The latter reason is why houses are often the best option, although any real asset serves the purpose of preserving our purchasing power well enough, protecting us from extreme crises.

- Monetary assets – only for short-term liquidity needs. Despite a reasonable performance since 1800, following the abandonment of the gold standard the real return has declined significantly and they are subject to unacceptable political risk.

This is a simple scheme, but it could be useful for steering us along the right path.

[You might think I am saying all this because I invest in equities for a living, making this a rather self-interested recommendation. This would be getting it the wrong way round. I invest in equities because, after analysing all the possibilities, I believe that it is the best way to sustain the purchasing power of my savings and that is what I am explaining. If it were better to invest in other assets, I would do so and I would recommend others to do the same thing.]