CHAPTER 8

Investing in Stocks (II): Opportunities, Valuation, Management

FINDING THE RIGHT OPPORTUNITY

Finding outstanding companies at a reasonable price is no easy job, but with time and patience the gems will gradually begin to surface.

Typically, we are looking for temporary problems which lower their share price to accessible levels. For example, an unfavourable currency movement which temporarily disrupts exports (for example, BMW or Thales were affected by a strong euro). Or digital migration, which can camouflage underlying business growth (Wolters Kluwer). This is a helpful starting point, but there will always be an element of doubt as to whether the fall is justified or not. And this can only be resolved after a major effort to get to the bottom of any issues raised in the analysis.

Our job is to sniff out these companies while minimising the risk of error, meaning it's important to find ways to reach them without calling into question their quality or sustainability. There are various ways of going about this, but initially we should look to work on familiar terrain, within our circle of competence. We may be in a position where we have developed better knowledge than the average investor; for example, if we have a passion for, say, technology or professional experience, such as working as an energy-saving engineer. We should try to capitalise as much as possible on any such advantages. Perhaps we are familiar with a company with a strong position in a new niche, or which enjoys impenetrable barriers to entry. Something which few people know about.

We shouldn't be alarmed by our supposed lack of experience, having such knowledge will help reduce the chances of failure. Just as an entrepreneur can improve their odds of success by starting out in a familiar field or sector, so can an investor. By contrast, an entrepreneur who creates a company without prior experience is much less likely to be successful, and the same applies to the uninformed investor. Creating a company, taking part in a private project, or investing in listed shares ultimately boil down to the same thing, and knowing the market is the key factor in determining whether the endeavour will be a success or not.

Thus, our first port of call should always be to work in familiar terrain, using implements that are known to us. However, if few ideas spring to mind or we really aren't experts in any area, then we should be on the lookout for other circumstances. The following are some examples of situations, generally relating more to technical market conditions than companies themselves. They are a good starting point and have given me much success in the past, though there's no guarantee that will be the case in the future.

Without dismissing other routes, the following conditions have helped me to find value in listed companies.

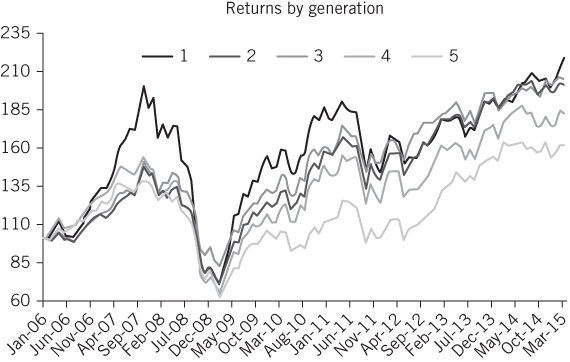

(1) Shareholding structure. By this I mean family companies or companies which have a single reference shareholder controlling the management. In Europe, they represent 25% of all listed companies. According to a 2015 Credit Suisse Research Institute Report,1 returns on family companies outperformed the market by 4.5% from 2006 to April 2015. Not a long time period, but it nonetheless confirms my own direct experience.

Source: Credit Suisse (2005).

These companies tend to have relatively underdeveloped public or investor relations departments, and generally pay less attention to the market, which penalises them for it. They are still listed companies, enjoying the liquidity and increased transparency this entails, but they remain somewhat aloof from the market.

In contrast to companies where the managers don't have a share in the capital, family companies' interests are generally aligned with other shareholders, enabling them to exert appropriate control over external executives. I worked in one for over 25 years and I can attest to the fact that I had to sweat for every euro of my wage packet. It also means they tend to reduce errors in allocating capital, since they have more of a long-term outlook.

That said, it is best to steer clear of companies where unqualified family members meddle in the management. This tends to weaken the company and generates conflicts of interest. In fact, historic returns decline as management passes from one generation to the next, from founder to second and third generation.2

Source: Credit Suisse (2005).

Another advantage of family companies is that they tend to approach accounting in a way that accurately reflects the company's underlying situation. They generally prefer conservative balance sheets, with little debt and a lot of cash. The market doesn't like this very much, but it's ideal for our purposes. Modern finance theory advocates ‘optimising’ the balance sheet, taking on the maximum amount of debt possible. We should prefer a less optimal approach. The primary objective of any company or venture is survival; after that we can talk about profits. Stable financial foundations are essential for this.

In Europe, family support is even more important still, since it's much harder to get rid of incompetent management than in the United States. As already mentioned, I can't recall a single case of activism in Spain where dissenting shareholders have successfully forced through a change.

Source: Bosset (2015).

Even though some family companies have ended up in insolvency – Pescanova, Abengoa, Parmalat and the like – and despite the potential for bickering or mysterious transactions with other family companies (problems that crop up from time to time), I need good reasons to invest in a company when there is no family or manager with a significant holding. The alignment of incentives is crucial.

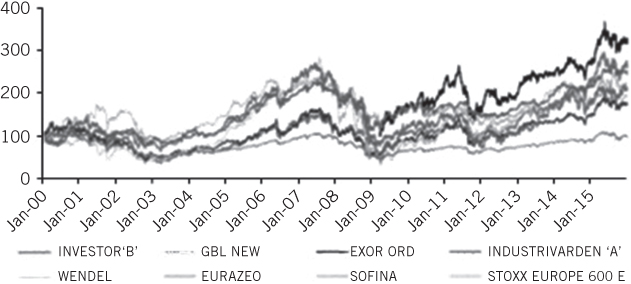

(2) Organisation of assets. Holding companies or conglomerates invest in unrelated businesses, which can sometimes lack coherence, and can deter investors. Very few of them trade at their intrinsic value, not even Berkshire Hathaway – the clearest example of a conglomerate. Accordingly, they don't reflect the sum of their investments.

As can be seen in the table above,3 such companies perform well in the stock market, and sooner or later end up trading at the value of their investments or even above. It might be necessary to hold on for quite a while until the trading discount is eliminated, and sometimes they only trade at their intrinsic value for a short while, but these are opportunities to capitalise on.

Conglomerates are generally pro-cyclical,4 performing better in bull markets and vice-versa. Some conglomerates have outstanding businesses buried among the fodder, and investing in the parent is usually a good way to access them at an enticing discount.

(3) Geography. Attractive distortions can also arise when a business is located in a different country from its headquarters or the market where it trades. Companies which are listed in Europe, but have an important part of their business in the United States – like Ahold or Wolters Kluwer – are an example of this. Such companies appear to lack a clear shareholder base or obvious natural owner. Ahold doesn't appear in Wall Street reports on American supermarkets, while the European reports fail to adequately price its American activity, which accounts for 50% of earnings. This leads to significant discounts relative to Kroger and other North American supermarket chains.

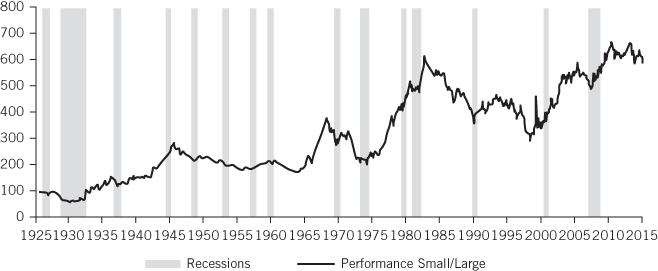

(4) Small companies. It stands to reason that the investment community pays less attention to small companies, providing us with the opportunity to uncover some great little gems. The main problem is a lack of liquidity, which can also apply to family companies, conglomerates, preference shares, etc. I already mentioned in Chapter 3 that illiquidity is a false problem and one of the easiest inefficiencies for patient investors to prey on. This can sometimes entail spending various years – or continually – patiently buying a stock to build up a position without affecting its price, or likewise various years unwinding it. Either way, small companies have historically delivered very positive results.5

In Spain, such companies have always been a key element of my portfolios: CAF, Elecnor, etc. A very long and varied list, which goes beyond Spain. These days it's less the case, since I have become accustomed to studying larger companies, but that's not an argument for disregarding them, especially in smaller portfolios.

Source: Laidler et al. (2016).

(5) Cyclical companies. This is probably the easiest and least risky way to find opportunities. Economic cycles need to be tolerated with enormous patience, but it's a reassurance to know that a falling share price is solely a cyclical effect and not due to some unknown competitiveness factor. Cycles always turn around. This means opportunities here are simple to analyse, as we already know what's driving the movements.

The biggest error we can make with the cycle is trying to predict the exact point of inflection, which is a total waste of our time. Instead, we should focus our efforts on stoically enduring the fall. We are never going to know exactly when the low point will come; we will always end up jumping the gun. The crucial thing is to keep buying throughout the fall, since the best results are obtained from the last investments that are made.

However, it's important to be very alert to two factors when looking at these types of companies: the company needs to be an efficient producer and able to operate under low prices; and it shouldn't be holding much debt. Failure to meet these two conditions can put our investment at risk, as the company may not make it out to the other side of the cycle.

The clearest example of a cyclical investment I have returned to time and again is the Spanish company Acerinox, which ticks both boxes, being an efficient producer and operating with little debt.

(6) Share types. I have come across discounts in European and Asian preference shares. These types of shares forego voting rights in return for the right to a bigger part of the dividends than common stock. Since we are normally investing in family businesses, losing the voting right shouldn't be a big deal, and the discounts on common stock can sometimes amount to 30–40%.

Supposedly, they are more illiquid, but some preference shares, such as BMW's, have a daily trading volume of around 5,000,000 euros, quite a lot more than various medium-size companies which don't trade at a discount. This is a clear market inefficiency. BMW and Exor are examples of investments I have made along these lines, as well as some Korean companies.

These types of preference shares are different from the American version, which is more like a bond.

(7) Long-term projects. Investors lack patience and the stock market isn't always the best place for such projects, leading to incorrect price formation and a possible investment opportunity. Patience is undoubtedly an investor's biggest asset, more so than intelligence or any other ability. It is an essential quality for such ventures.

It's surprising how schizophrenic some investors can be. In their professional life, which might be very successful, they can be willing to invest in a business or new machine and give it time – two or three years – before gauging the results of the project. While at the same time, they expect their investments in listed shares to yield an immediate return. Unfortunately, the qualities which make them good private investors don't translate into their stock market endeavours.

I repeat, patience is the single most important attribute for investing effectively. A patient and reasonably well-informed investor has the philosopher's stone in their hands: the holy grail.

Source: Value Investor Insight, Bloomberg.

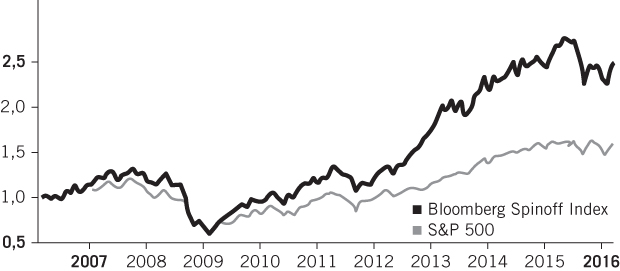

(8) Spin-offs or asset separations. Opportunities can arise which are worth exploring when a division of a company is split off to become its own entity. Over the 13 years from 2002, the Bloomberg US spin-off rose by 557% compared with a 137% increase in the S&P 500.6 This inefficiency arises from various factors: firstly, with spin-offs the incentives change and executives are financially and professionally motivated to do a better job in managing the new company (perhaps they even managed it before, but the new incentives improve results); secondly, there may be a lack of detailed information on the new business, since we are not talking about a stock market launch (IPO) but rather a placement among existing shareholders; thirdly, the company's existing shareholders may not want to have a position in the spin-off, meaning they will immediately offload their shares, providing an opportunity.

(9) Free lunches. These can arise in any of the above cases, or in isolation, and are another way to the tilt the odds in our favour. Free lunches appear when a stable business – which justifies its share price – comes into possession of a tangible asset or an early-stage project with potential to mature and which is not well priced by the market. These amount to free – or nearly free – lunches, since their remoteness, whether in time or perhaps geographically, means the market tends to overlook them.

They represent one of the most attractive ways to invest, combining security with potential for outstanding upside. What's more, this is exactly the type of mental attitude that we should always look to develop. A clear example for me was the case of Ferrari within Fiat, and under the umbrella of Exor. When I first invested in Exor, investors were correctly pricing its two main assets, SGS (Société Générale de Surveillance) and Fiat Industrial, supporting the overall valuation. However, they failed to take account of Ferrari, which fell under Fiat Auto, a manufacturer of affordable but relatively uninspiring cars and vans. Ferrari was a free lunch waiting to mature. Little by little the market warmed up to it, with the company ultimately being placed on the New York Stock Exchange in 2015 at a bumper price.

The above are some situations which can produce good opportunities, but market distortions can arise in a variety of ways. For example, companies with better than expected growth, or a successful restructuring, or a change of management, etc., or any other potential upside that has not yet been grasped by the market. Rest assured, they will appear and we can find them.

It could be argued that the discounts on conglomerates, family companies, or other situations are something that is more permanent feature than opportunity, but this is not the case. From time to time there will be moments when the discounts begin to close, allowing us to unwind or sell positions, depending on other market alternatives. It's not an absolute certainty, but the probabilities are indeed very high. I will go into this in more detail later on.

Once we have eventually uncovered some quality stocks which we feel comfortable with, we can begin to increase their concentration in our portfolio. However, when investing directly in stocks it's vital to diversify the portfolio among a minimum number of stocks. The exact figure isn't important, although five to six stocks would be a bare minimum. Thereafter, the total number of stocks in the portfolio will depend on how much knowledge we acquire on different companies, but without going beyond a reasonable number, say 15 to 25.

COMPANIES TO AVOID

While there are some areas that are ripe for reaping rewards, there are others which are already overexploited. That's not to say there are no good investments to be found, but the chances of this happening are much lower, increasing the risks of us running into a dud. Some examples are as follows.

(1) Companies with an excessive growth focus. Growth is good and beneficial if it's the result of a job well done, which generates resources over time which are reinvested in increasing the strength of the company, but this tends to be more the exception than the rule. The obsession – because that's what it is – with high-growth targets is extremely dangerous. The goal should be for the largest number of clients possible to enjoy the product on offer but without exploiting loopholes or taking shortcuts. This isn't easy for large organisations, meaning that it's important to be careful when analysing them.

Once again there is an agency problem: who are the company's management working for – themselves or the shareholders? Growth is a hugely attractive call signal, which increases the halo or prestige around managers, but it's only a good thing if it's healthy.

(2) Companies which are constantly acquiring other companies. This is linked to the previous point and can make matters worse still. If the acquisition is not focused on increasing the competitive advantage of the main business, it can end up becoming a rueful folly, or what Peter Lynch calls ‘diworsification’, diversifying to deteriorate. Growth can also bring with it two other problems: first, more complex accounting can more easily conceal problems; and second, each acquisition ends up becoming bigger than the last, increasing the price and therefore the level of risk.

It's worth reiterating how detrimental it can be when some managers feel the pressure or the desire – after selling a substantial part of the company – to buy another of a similar size, instead of returning the money to the shareholders. It brings to mind cases such as Portugal Telecom; Unipapel, Repsol, and Azkoyen in Spain; and Clariant in Europe.

(3) Initial public offerings. We've all fallen into this trap and we have to be on the watch for it. According to a study by Jay Ritter, Professor of Finance at the University of Florida, companies who float on the stock market via an IPO post 3% lower returns than similar companies after five years.7

There is a simple reason for this: there are clear asymmetries in the information available to the seller and what we know as purchasers. The seller has been involved with the company for years and abruptly decides to sell at a time and price of their choosing. The transaction is so one-sided that there can only be one winner (by the way, somebody received a Nobel Prize for pointing out that there are information asymmetries in the markets!).

(4) Businesses which are still in their infancy. Old age is an asset: the longer the company has been going, the longer it will last in the future. In fact, a recent study shows that there is a positive correlation between the age of a company and its stock market returns. That is logical, because it takes a certain amount of time for a business to get on to a stable footing, depending on the level of demand and competition. Until this happens, we are exposed to the high volatility inherent in any new business, with an uncertain final outcome.

Taleb8 explains this very accurately, applying it to various aspects of our life, even our own life.

Despite the above, I am guilty of having made the error of investing in new businesses, which invariably led to losses. After having had these experiences even Google seems like too much of a whippersnapper, still needing time to become settled.

(5) Businesses with opaque accounting. Whenever there's significant potential for flexible accounting, being able to trust in the honesty of the managers and/or owners is essential. Long-term contractors in the construction sector, or in infrastructure or engineering projects, are examples where there is scope for flexible accounting, with latitude to delay accounting for payments or bring forward income.

We could even include banks and insurance companies in this category, where the margin for accounting flexibility is very significant and it's relatively simple to cover up a problem for a while, compounded by having highly leveraged balance sheets.

Prior to investing in these types of businesses, it's absolutely imperative to be certain we can trust the managers or shareholders (to the extent that we are able to determine this). No one forces us to invest in them, so the burden of proof is on the company.

(6) Companies with key employees. These are companies where the employees effectively control the business, but without being shareholders (the latter could even be positive). For example, many service companies reportedly have very high returns on capital, but only because capital isn't necessary: investment banks, law firms, some fund managers, consultancy companies, head-hunters, etc.

The creation of value in these businesses benefits these key employees, while the opportunities for external shareholders to earn attractive returns are limited, despite supposedly high returns on capital employed.

(7) Highly indebted companies. As somebody once said, first give me back the capital, then return something on it. Buffett also remarks that the first rule of investing is not losing money, and the second and the third… Excess debt is one of the main reasons why investments lose value. We don't need to flee from debt at every opportunity, when it's well used it can be very helpful, but it shouldn't have much weight in a diversified portfolio.

By contrast, markets don't particularly like companies to hold cash, rightly fearing that such financial well-being might lead to bad investment decisions. I have always ensured that over half of the companies in the portfolio have ample cash: I sleep well, making the most of incorrect market valuation. I am not worried about excess cash, provided that capital is reliably allocated.

(8) Sectors which are stagnant or experiencing falling sales. While it's not worth paying over the top for growth, on the flipside, falling sales can be very negative. Quite often these companies can cross our radar because of the low prices at which they are trading, but over the long term, time is not on our side with them. Sometimes sales will recover, but mostly the opportunity cost is too high, given that the situation can persist for some time. I have encountered my fair share of these: Debenhams, printing companies, etc.

(9) Expensive stocks. It's obvious but worth spelling out. I don't think I have ever tried to buy a stock valued by the market at over 15× earnings. Perhaps it's a genetic disposition, or a habit I've picked up, but in reality, expensive companies have historically obtained the worst results, because good expectations are already priced in and because it's less likely that the price will jump from – say – a P/E ratio of 16 to 21 than from nine to 14.

That's not to say that good results can't be obtained from buying the above types of stocks, but it's an additional hurdle which I have always preferred (and recommend) to avoid.

These aren't the only examples of companies to avoid, but – once again – they are a good starting point.

CAPITAL ALLOCATION

Suppose we have found a good company at a decent price. We have now completed the essential part of choosing our favourite stocks. However, by definition this company generates a lot of earnings, and the managers have significant flexibility in terms of how they allocate this money, with a wide range of options available to them. Therefore, it's important that the capacity to generate value through competitive advantages is also matched by an appropriate allocation of earned profit.

As already mentioned, as shareholders the only thing we ask of the management board is that they give consideration to repurchasing and cancelling shares. We obviously believe the shares to be undervalued – otherwise we wouldn't have invested – meaning that a cancellation would create value. It's not that we're demanding they do this, but it should be on the list, alongside other main options such as dividends, investments in assets for growth, and acquisition of other companies to increase the company's competitive advantage. The board should decide between these options based on the highest expected return and consequent value creation for the shareholder.

The only way we can get a fix on capital allocation is by studying the managers' track record and the company's decision-making processes. It comes down to both a quantitative and a qualitative analysis based on criteria, with experience being assigned a very high weight. As previously mentioned, the greater the extent to which managers have shareholding interests, the more likely it is that their interest will be aligned with minority shareholders, but this step shouldn't be overlooked in any case.

VALUATION

Valuation is the last step in selecting stocks. It involves making the necessary calculations to determine the target price which will serve as our guide. This is the last step and probably the easiest part of the investment process.

On my desk I have a calculator which adds, subtracts, multiplies, and divides. Plain and simple. There's no need for anything more sophisticated, since most of our time will be spent analysing the companies we're interested in. Our goal is to be among the minority of investors, the top five or so, who are best acquainted with a given company and its circumstances. Analysing does not involve building complicated mathematical models with discounted cash flows (and, for example, with forecasts for annual earnings over the next 15 years). Instead, it's far better to have a good understanding of the business and be able to determine a particular company's capacity to generate future earnings. The goal is not to precisely forecast earnings each year, but rather to set out a logical range in which they are likely to move according to the business's characteristics. Doing so requires reading, delving into the companies, asking, learning, and reflecting; not constructing complicated models.

Once we have a figure for normalised earnings (i.e. under stable market conditions – neither boom nor crisis) we can apply an appropriate multiple and arrive at our valuation. Discounting cash flows is a neat stylistic exercise, but adds little to the valuation. I would use it only very occasionally for extremely stable and predictable businesses – motorways, gas or electricity networks, etc., where by their very nature the likelihood of erring is very low – but in other cases it adds practically no value, since the chances of correctly predicting earnings in – say – year seven are minimal. It doesn't tell us enough to warrant the time spent performing the calculation.

The multiple to apply to these normalised earnings will depend on the quality of the business. A very reasonable – and probably the most suitable – approach is to use the stock market average for the last 200 years. This average is 15, which is equivalent to an ‘earning yield’ of 6.6% (1 × 100/15), in line with the long-term real return on equities. Setting this as a target return seems pretty sensible. For some outstanding businesses we could apply a somewhat higher margin of between 15 and 20; while for more mediocre businesses, with limited barriers to entry, we should push it down to between 10 and 15. For most businesses, 15 is an appropriate multiple.

Once we have performed the valuation, we should invest where we find the largest discounts relative to this target valuation, calculated according to the multiple. Other qualitative factors will also influence the investment decision, the most important one being the quality of the business and – closely related to that – our confidence in the valuation we have performed. Quality and confidence will help us decide the appropriate weight for each stock in the portfolio.

Overall, the valuation will give us a target price which will serve as a light to guide us in our buy–sell decisions, depending on the available alternatives.

NORMALISED EARNINGS

Normalised earnings are the key to our valuation. ‘Earnings, earnings, earnings’, as Peter Lynch wrote. Calculating normalised earnings requires us to have an in-depth understanding of the company's business and its market position. The companies' accounts provide us with a first snapshot, although at this point it's not necessary to analyse them in any great detail yet. In this initial approximation, we can limit ourselves to a few headline figures, which will help us determine which companies might end up being an attractive opportunity worth investigating in greater depth.

It will take some time to understand the market and the company's position – days or weeks, depending on how complicated or novel the sector is. Once we have a basic view on the company's position and future (I say ‘basic view’ because the analysis can take years), we should start to pick apart the accounts. Our initial goal in this part of the analysis is to verify whether the accounts are an accurate portrayal of the company's state of play, enabling us to then move to estimating normalised earnings.

(1) True reflection of the company's state of play. As we all know, accounting is a flexible discipline that can be stretched to fulfil a variety of needs. To avoid errors and future problems, we should focus on:

- Cash flow analysis. The income statement is important, but the first way to test whether the accounts are credible is by checking whether the cash is real. It's no use if the company is supposedly obtaining good results but this isn't reflected in cash at the end of the financial year. This type of analysis, for example, helped limit our losses in Pescanova: at the end of the year, cash just wasn't rising as it should have been but debt was going up; this led us to pare back our exposure, though unfortunately not completely.

All companies publish cash flow in their annual accounts, and there are various books available on how to focus our analysis of this issue.9

The ideal company in this analysis will generate more cash than implied by its P&L account. This is a sign of very conservative accounting and that earnings are being ‘stashed’.

- Credibility of the income statement. This is the flipside of the cash flow analysis. The main problem arises when accounting is excessively aggressive in regard to income or expenses, reporting income for a year that still hasn't materialised and failing to recognise outlays that have taken place. It's essential to be able to identify either of these accounting tricks.

Three of the most common problems in recognising costs stem from: provisioning, which can be too low given the company's situation – think of the Spanish banking sector between 2005 and 2011; the company's policy on fixed asset depreciation, which may not reflect real asset depreciation; and, finally, excessive capitalisation of expenses.

Once again, it's not only about looking at the negative side of the analysis. There are some very conservative companies that conceal part of their earnings capacity, perhaps to hide the underlying attractiveness of the business, or to benefit from a more favourable tax treatment.

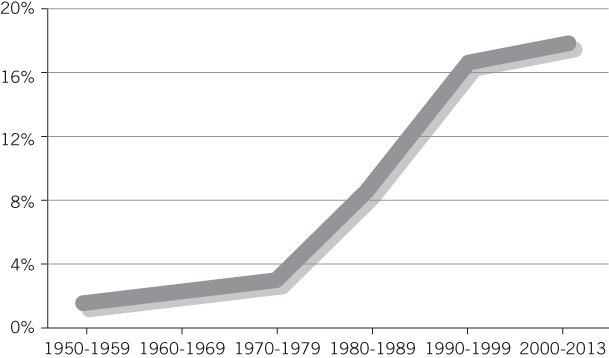

A final problem is the tendency to classify some recurring expenses as one-off outlays. Repeating this year-in, year-out clouds the analysis and makes it harder to discover the real capacity to generate earnings. As Lev and Gu point out (see the chart on the next page), one-off expenses account for nearly 20% of reported earnings.10

- The balance sheet. Our main responsibility regarding the balance sheet is to investigate whether there are hidden or off-balance-sheet liabilities. These could be pensions liabilities, costs associated with closing down factories, mines, etc., or any erroneous calculation of some type on provisioning for possible future losses.

An unexplained increase in certain current headings, such as stocks or account receivables, could suggest that the reality is more challenging than the income statement makes out.

The reverse can also be true here: with the existence of hidden assets making the company more attractive, such as real-estate assets not used in the business or subsidiaries not related to the main business, the brand or other intellectual property which increases in value over time, etc.

By going to some effort, we can develop a reasonably accurate impression of the company's true situation.

Source: Lev and Gu (2016).

(2) Normalised earnings. Once we are convinced that the accounts are an accurate reflection of the company's real situation, we can start thinking about the normalised earnings calculation. The company may be going through an unusual situation influenced by temporary factors which obscure its real capacity to generate earnings. We need to delve into this.

- The economic cycle. Highly cyclical companies will never be in a stable situation, since the ups and downs of the cycle make it hard to know what ‘normal’ earnings look like. It's not about predicting the cycle, rather it comes down to understanding where we are right now, which may be an extreme, good, bad, or plain normal situation. There are various different methods we can use to adjust earnings in the face of this difficulty: taking the average of results over the last 10 years, adjusting for inflation; taking maximum and minimum earnings over the last 10 years and using the mid-point; or any other commonsense criteria.

- Disruption to supply or demand can bring about exceptional situations, and we know that investors tend to extrapolate the current situation to the future. It's a huge error, since economic agents will react to such problems, and they will gradually be resolved.

- The company in question might still be in its infancy, but capable of maturing over time. It's important to consider the potential to generate earnings in the future, which have not yet materialised.

- The previous issues could affect a part of the company, tainting the overall valuation of the rest of the business. A normalisation will need to be applied to these ‘loss’-making businesses, otherwise we will be damaging the whole company. In the worst-case scenario, we can value the division at zero, taking account of the costs involved in a possible wind-up.

Overall, normalisation helps to refine the valuation, partially mitigating the difficulties involved in predicting the future.

INDEBTEDNESS

Although indebtedness doesn't directly impact on the valuation, it's important to be very aware of a company's debt levels, analysing its capacity to pay back debt: size, term, restrictions, etc. We should steer clear of businesses that are highly indebted, since they can negate our estimates of future earnings. Debt improves the return on capital, but the increased volatility from interest payments can become impossible to bear. The limit for acceptable levels of debt depends on the stability of the business; the more stable – with an easy to predict outlook (motorway toll road, electricity networks, etc.) – the more manageable the debt.

The same applies both to the business world and our own personal situation.

The undeniable advantage of working without debt or other liabilities is that we can withstand any situation with the necessary peace of mind. Debt requires us to be more precise with our predictions than is desirable, especially given the near impossibility of correctly forecasting what will happen and the inevitability of devastating surprises.11

The goal of this book isn't to give a lesson in finances or valuation, there's plenty of literature on that; I have simply tried to set out some general rules to enable us to tackle the task of putting together a reasonable valuation. Furthermore, as can be seen, such valuations do not require very sophisticated tools.

MARKET RECOGNITION

Some readers might argue that the approach set out in this chapter – and the book in general – depends on the time it takes for the market to wake up to the undervaluation which we have identified.

I don't deny that it can take some time for the market to come to its senses, but if our analysis has been sufficiently rigorous, we should welcome this as it will allow us to increase our positions.

It might also be claimed that we won't have enough liquidity to strengthen these positions, but in reality not all stocks move in sync and these differences can enable us to adjust our portfolio to these relative movements. I am constantly tweaking the weights of my stocks according to their performance. If I have positions in two stocks and one goes up by 20% and the other falls by 20%, I almost automatically sell positions in the first to allow me to reinvest in the second. Therefore, even in the absence of liquidity, we can afford to patiently await future price rises.

The following table calculates the annual return depending on the time it takes for the expected total upside (1.5×, 2×, or 3×) to materialise. As can be seen, if we think our portfolio will go up in value by 50% (1.5×) over time, even if it takes 10 years to get there, we will obtain a 4% annual return. And this is the worst-case scenario, which will improve if the upside is greater or takes less time to materialise.

Annual Return Over Time

| Years | 1.5× (%) | 2× (%) | 3× (%) |

| 1 | 50 | 100 | 200 |

| 2 | 22 | 41 | 73 |

| 3 | 14 | 26 | 44 |

| 4 | 11 | 19 | 32 |

| 5 | 8 | 15 | 25 |

| 6 | 7 | 12 | 20 |

| 7 | 6 | 10 | 17 |

| 8 | 5 | 9 | 15 |

| 9 | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| 10 | 4 | 7 | 12 |

Source: own calculations.

In fact, in the funds I have managed there has never been a period of more than nine years with negative returns. This is consistent with the table above, given that my estimated upside potential has always been above 50%.

In any case, some factors can speed up the process:

- New managers are seldom a quick fix, but they can help catalyse changes, putting companies on the right path and focusing them on their competitive advantages.

- The circumstances which cloud the ability to generate results can change. Currencies, technological changes, or any other event which may have concealed a business's advantages can drop out.

- The economic cycle can change. Nothing lasts for ever and we should be mindful of that.

- Sometimes it just happens: the gap between value and price gradually closes. Experience tells us that for one reason or another, the market always ends up recognising a company's ability to generate earnings.

I don't like talking about catalysts, which by their very definition are unpredictable, otherwise they would be reflected in the price. However, share buybacks will always help. When we come across an undervalued company which repurchases its shares, we are looking at the only catalyst under the direct influence of the company and its shareholders. As investors, we have to make this point to other shareholders.

I feel like I am repeating myself, but patience is the key attribute for investing successfully, and it's what should keep us going during the wait.

THE PERFECT STOCK

In summary, the perfect stock is a preferred share in a medium-size company with a family holding company structure, trading on the wrong market, with a cyclical component and/or long-term investments. A good example of this for me in recent years has been Exor (the holding company for the Agnelli family), which ticks nearly all the right boxes: family company, holding company structure, preference shares, good businesses (CNH, Ferrari, SGS – the latter until it was sold) mixed with less attractive ones (Fiat), trading in Italy, but with global assets, cyclical in nature, and with a long-term perspective. All in all, a real gem which has performed accordingly.

It's not common to find such stocks, but it's possible. In this case I came across it in the weekly Barron's, a publication available to everyone. Sometimes you have to investigate a bit more, but with patience they can be found.

How is it possible to find such opportunities? Shouldn't they be obvious to all investors? Is everyone else around us blind? These and similar questions deserve a response before completing our journey through the investment world, and Chapter 9 will address them. First though, I want to sketch out a few key ideas on managing an investment portfolio.

PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT

Some Ideas on Managing Portfolios

Management is more than the sum of the purchase of attractive stocks. It involves a degree of strategy about the objectives for the portfolio, taking a view on the overall lines of action. It's not always possible to have an overarching strategy, but it is at certain times and it can be very beneficial.

The first step (optional, depending on the circumstances, as we will see) involves trying to acquire some idea about where we are in the cycle. For example, whether we should be moving towards defensive stocks, or – on the contrary – starting to be more aggressive, if we judge the declines to have been sufficient.

This doesn't require having a clear idea of the general state of play in the markets and the economy, but it is helpful to analyse the message coming from the types of stocks that interest us, so as to draw the right conclusions about what's going on. If some stocks in a sector have taken a particular hammering, it's likely we will be at the bottom of the cycle in that sector.

Overall market developments will also give us some insights: if there have been lots of very strong rises, we will be heading towards the end of a cyclical expansion, while after a series of large losses, we will doubtless be close to the bottom.

However, there's no guarantee that our analysis of the cycle will be successful. In many cases the only thing we can say with any real conviction is that the global economy grows by 3% a year, but we don't know whether this year it will be closer to 2% or 4%. If we are able to have some degree of clarity on the overall or sectoral cycle, then the next step is to consider which types of stocks will help us in this context. Obviously, we need to buy the most aggressive stocks during low points in the cycle, even if it can be challenging to overcome the mental barriers to doing so in such a negative environment. And vice-versa at the top of the cycle.

Designing the appropriate strategy for the general or sectoral cycle can be what adds most value to a portfolio. In fact, some ‘scholars’ believe it's the only thing that adds value as specific stock selection is a zero-sum game, where you don't add value. My experience is that all phases of the investment process contribute, though it's true that it can be easier to add value through portfolio design.

Other relevant factors:

- Diversification. The future is hard to predict; situations can arise which hadn't even occurred to us. Often we are prepared for past surprises – no longer surprises as such – but not for the unexpected. And we can be sure they can creep up on us one way or another. As such, our portfolio should be prepared to withstand any situation, be it a market collapse or a boom, inflation or deflation, for all possibilities. It must be agile and resilient against any eventuality.

We also have to insulate the portfolio from our own errors, whether they be our view of the cycle or our choice of companies. We have to envisage how our portfolio would be affected by the opposite scenario to what we are expecting; how it would survive.

Diversification is the clearest way to prepare the portfolio for any eventuality. Having at least 10 stocks gives us a reasonable amount of diversification. If we are managing on behalf of others it can be helpful to hold a few more, creating a portfolio of some 20–30 stocks. After that, there need to be strong arguments for increasing the number of stocks.

In my case, the main reasons come: firstly, from the type of investment vehicle used – public funds – which are subject to relatively strict legislation; and, secondly, a specific seeding strategy based on holding smaller positions.

- Stock selection should be bottom-up. Which came first, the chicken or the egg? At the risk of contradicting myself, stock selection is the first step in managing portfolios, except when this selection provides us with enough information to design a strategy straight out of the box before investing. To avoid confusion, suffice to say that if the selection of stocks and the market itself don't provide us with enough information, we can safely disregard having a portfolio strategy and just focus on selecting attractive stocks.

In doing so, the guidelines set out in this and Chapter 7 will enable us to avoid wasting time on companies which don't stand up to greater scrutiny. Furthermore, in practice, it's important to be very flexible: avoiding slipping into generic asset allocation, both for sectors and regions. If emerging markets are attractive, then we have to invest what we consider necessary. If it's 50%, so be it.

If we don't understand banks or new technologies, then it is best to avoid them. If we are engineering enthusiasts and we can see opportunities, then carpe diem!

- Pay particular attention to the weight of stocks in the portfolio. As already mentioned, over the years we got it wrong on a number of stocks, more than 40, but crucially they were seldom significant investments. We must be very sure of our investment if we are going to assign it a high weight in our fund, never doing so if the company is indebted.

Bear in mind that it's extremely difficult to discern and accept investment errors: we always end up giving the benefit of the doubt to the company, since after investing so much time studying it, we find it deeply unsatisfying to sell and think that we are throwing it away. One of the ways to get around this problem is by only having small exposures to the more dubious stocks.

- Changing weights. One of the ways to add value in asset management is by changing the size of positions in stocks.

In Europe, regulated mutual funds enjoy almost total exemption from capital gains tax. This means that shares can be sold at virtually no cost, especially bearing in mind that brokerage fees have fallen significantly to 25 basis points (0.25%) in the worst case, which is barely noticeable in the context of price movements of 15% or 20%.

As previously mentioned, the argument for continually adjusting is one of simple probabilities: if a stock in a portfolio rises by 10% and another falls by 10%, then there has been a relative movement of 20% which we can capitalise on. The logical thing to do, once we have studied the movements, is to lower our position in the stock that has gained value and increase it in the one that has fallen.

Some investors prefer to wait until the stock has reached the target price before offloading the entire position, or take other approaches. However, it's highly likely that our simple approach increases the potential of the fund, since it's unlikely the valuations of the particular shares have moved in the same proportion.

- Sectoral effort. We should focus on attractive sectors. It's impossible to be on top of every sector. As unspecialised generalists we should discriminate between sectors that are worth following – which form the focus of our efforts – while leaving the rest to one side. Not all sectors are equally attractive all the time, and it can take years for the level of interest to shift.

By focusing, I mean devoting the bulk of our resources, especially time, to the most attractive sectors. We should keep an eye on other sectors, being aware of their existence, but they shouldn't eat up our time for the moment.

The same approach applies to choosing sectors as it does when we look for a specific stock: we need to be on the lookout for poor stock market performance, which creates general dismay or even personal disdain about the sector among investors. This is the starting point for us to explore whether it makes sense to invest or not.

Sectoral or regional specialists suffer from a basic problem of being limited to the specific market in which they are able to operate. They have to buy something and they end up doing so regardless of whether it's attractive. The same thing happens with regional representatives in any business: they end up selling, even if not very profitably, because their position is on the line. As the former Chairman of Acciona, José María Entrecanales, used to say: ‘Be careful with business representatives in a country, because they always end up taking on work, even if it's not profitable’. He was referring to his main business of construction, with great insight and lucidity as ever.

Finally, when ‘experts’ talk about sectoral weights in a portfolio, what they are talking about is the relative weight of sectors in the market, which normally don't diverge much. In other words, if the financial sector represents 20% of the market, they might advise investing 15–22% of the portfolio. When I talk about sectoral effort, I'm referring to dedicating resources to it in order to decide whether to invest or not. The decision should be made without prejudice to the sector's weight in the market.

By moving from less attractive to more attractive sectors we avoid wasting time, which is an extremely scarce resource in investment analysis. There will be time in the future to return to sectors left to one side.

A Day in the Life of a Fund Manager

It's almost a cliché to talk up the benefits of consistency, essentially habits, which underpin the achievement of optimal results over time.

In my case, I've been fortunate enough to keep to a stable routine over the years, despite the increasing size of the funds that I manage and the number of clients (not to mention my own family). Nobody can be sure what the ideal path is to achieving one's objectives, it's trial and error for all of us, but I confess I've been reluctant to change my ways having seen early on that they work for me. Here's what I get up to.

I start my day reading the press. Each day for the last 20 years I have read Expansión (a Spanish economics and business newspaper published in Madrid) and the Financial Times (FT). These two papers are my core reading. I used to also read another Spanish daily economics newspaper, but I gave up in the end as it was too similar to Expansión, temporarily substituting it for papers covering other issues that were of relevance at the time, such as the French Les Echos or the Chinese China Daily.

Among foreign economic press I have always stayed loyal to the FT as a European paper, although I prefer the Wall Street Journal's editorial and opinion columns, which take a less interventionist stance. The FT's ‘Lex’ column is, in any case, a must read; it analyses companies briefly but in sufficient depth to add value. Nowadays I don't learn so much from the FT, but it gives me a guide as to where market consensus is and how to act accordingly. My core weekly reading consists of Barron's and The Economist, and it's also worth mentioning Value Investor Insight, where a couple of interesting asset managers set out their ideas each month.

Nowadays I don't read general information newspapers or listen to news on the radio or television. I am fed up with their poor understanding of the issues – at least on the topics I know – and their general negativity about a world which every day is offering more people the chance to live a decent life.

After demolishing the press, I get underway with various routines, which can depend on the circumstances: reading company or sectoral reports (I never read reports on so-called investment strategies), company visits or visits from companies to our offices, and contacts with sector exports or people familiar with companies of interest to us. Probably most of my time is spent reading alone – a passion for reading is vital for a good analyst or fund manager. The Hollywood portrayal of traders shouting into their phones is a far cry from our oasis of calm. Coming to our offices is like entering the National Library: Shh, you're not allowed to talk! The true value investor, who deserves my utmost respect, is somebody who devotes their life to their passion of reading. Nobody can spend their life studying for 50 years – which is what we do – if they don't enjoy it.

I have never been a fan of scheduling formal team meetings; I prefer for ideas to be voiced as they arise, or following meetings with companies or expert conferences. In reality, I seldom spend much time with the whole team together.

Until recently, travel was very important, but less so these days thanks to technology. Even so, I will tend to travel once or twice a month, normally in Europe.

I don't follow the markets until they close. I formally took the decision when the Spanish market opening hours were extended from 9:00 to 17:30. It struck me as being too long, and I didn't want to stop doing other important things to follow what was going on. It was a one-man boycott, which logically hasn't affected the world, although it has implications for me personally, since I spend all my time on analysis.

As I normally like to handle the daily management of the portfolios, the dealers or another team member will let me know if a particular stock has experienced a sharp movement or is closing in on a limit that interests us, so as to make the call on whether to buy or sell.

Generally, I don't have any idea what the market is doing over the course of the day, although I can usually make a pretty good guess based on movements in the stocks that interest us. When the market closes, at 18:00, I review the prices of our stocks and any interesting developments in other stocks that we're following. This information provides the basis for taking decisions the day after.

Some fund managers swear by the need to sleep on decisions. I agree. Giving yourself at least a day helps to fend off unnecessary haste.

I have the good fortune of having completely streamlined my involvement in investor relations tasks, which are the bane of most asset managers' lives. In recent years, my general rule has been not to see new clients, except in exceptional cases, while trying to maintain the relationship with long-standing clients. This increases the importance of annual investment conferences and the work of the commercial team, who I try to ensure are sufficiently well informed.

This enables me to keep a reasonable schedule; I am never in the office after 8:00 in the evening. I think it provides the right balance with family life, also bearing in mind that I use the journey to work and back, an hour all together, for reading. The latter is often quite varied and not necessarily strictly work related, though usually it complements that very well.

Overall, the common element is consistency, combined with a long-term passion for what I do, which together creates a very positive effect, as Angela Duckworth explains.12 The same basic routine every day, come what may. There have only been two brief moments when I stopped reading the daily news, in the immediate aftermath of my accident in 2008 and after resigning.

This consistency helps develop skills which, as they become refined, give broader meaning to the work beyond myself. These days I don't only do it for personal satisfaction, but also for a wider benefit. For me it's about giving peace of mind and independence to other people in a key part of their life: their savings.

A Case Study in Management: BMW

BMW is a very representative example of my approach to investing and managing. It's a company with an understandable business, with a well-established family serving as long-term reference shareholder. The company enjoys a certain amount of growth and is subject to cyclical fluctuations, but it also has deep cash pockets to defend itself.

The main appeal is its brand, which allows it to sustain much higher margins and returns than most of its competitors, including its rivals in the luxury segment, such as Daimler, the owner of Mercedes. BMW's average sales margin has hovered between 8% and 10% over the last 10 years, enabling it to post a return on capital of 25% in relation to the pure automotive business. This is slightly reduced by lower returns on finance activity, which puts the group's ROCE at between 15% and 20%.13

Another factor in originally investing was the enormous expected sales growth in China. Sales to China at the time of investing were limited but set to experience strong growth, given Chinese consumers' preference for status symbols, for which BMW fits the bill (Chinese sales jumped from 44,000 cars in 2006 to 463,000 in 2015). In actual fact, growth was far stronger than I had ever imagined.

I also considered BMW to be one of the most technologically and environmentally advanced companies, offering a wide range of vehicles, with the (at the time) recent launch of the new X-range of multipurpose SUVs.

But the key factor is that it was a company where the Quandt family held control without meddling in day-to-day management. They made a major error in the 1990s by buying the Rover Group, but have since learnt to be more careful about unhealthy diversification – although the upside of the Rover purchase was coming across Mini and Rolls Royce, which have provided good long-term results. This family management is embodied in a 20-year holding of a similar number of shares, around 650 million, financing all growth from cash flow.

We first bought into the company in spring 2005, purchasing common stock trading at 35 euros. This accounted for 0.7% of the international portfolio. At that time we purchased common stock because the discount on preference shares wasn't excessively large, around 10%.

Over the course of that year BMW continued to post record results, while we refined our knowledge of the company by speaking to experts and travelling to Germany to visit them in Munich. We also visited Daimler and Volkswagen. Furthermore, I dusted off my German to read about the family's turbulent and fascinating story in Die Quandts.14 So, when the share price slipped in 2006, we took advantage to increase our position to 2.5% of the portfolio, elevating it to the status of a significant stock pick. We were still buying common stock, since preference shares were trading at similar levels, even closing 2006 one cent above common stock at 43.52 euros.

I began buying preference shares in the second half of 2007 – at the start of the financial crisis these had fallen more sharply than common stock and were trading once again at around 35 euros – with a 15% discount on common stock. We bought the equivalent of 4% of the portfolio. Despite being much less liquid (around 50,000 shares were trading daily compared with 2,000,000 common shares), we were reassured by the fact that employee incentives were being paid out using preference shares, which also have a statutory right to a somewhat larger dividend. The overall position amounted to around 5%, as I sold off some normal shares to avoid excessively increasing our exposure.

The financial crisis of 2008 and the beginning of 2009 pushed preference shares down to a minimum of 11.05 euros per share, and we took advantage to increase our position to 9% of the portfolio, close to the maximum legal limit, with the average purchase price standing at 20 euros per share.

At that time the company's capitalisation amounted to seven billion euros. This was a steal, bearing in mind that the cash from its industrial activity and the book value of its financial activity were above that amount. Something we pointed out in our March 2009 public presentation. What's more, the company's cash generation was positive throughout these two years. In other words, cash went up during the worst crisis in recent decades.

With cyclical companies the key is to capitalise on cyclically driven price movements. We bought throughout the fall, constantly increasing the size of the position and continually lowering the average purchase price. I didn't know when the share price would touch bottom, but I knew we would be buying on that day, as proved to be the case.

In 2009 the fund was now only holding BMW preference shares and the share price doubled, closing at 23 euros. Throughout the year we sold off shares to avoid exceeding the legal limit and reduce the exposure, which at the end of the year stood at 7.78% of the global portfolio.

In 2010 the share price nearly doubled again, closing at 38.50 euros. We continued selling, but kept the weight in the portfolio at 9% for quite some time. At the end of 2013 we reduced the position to 7.58%, with the share price ending the year at 62.09 euros.

In sum, during the nine years since our initial investment, the share price had gone up in value by 75%, outperforming the market. But, crucially, by not letting up on buying during the fall, the average purchase price fell and we were able to triple our investment from 20 euros to 62 euros (plus 11.87 euros in dividends, an important amount representing 60% of the initial investment). We weren't anticipating the market crash in 2008, but thanks to Lehman Brothers what would have ended up being a reasonable return of 75% in nine years became something exceptional. As the saying goes among some warped politicians, nothing like making the most of a good crisis…

The factors behind the strong stock market performance reflect BMW's own excellent performance. In 2005, BMW sold 1.33 million cars; in 2013, 1.96 million. In 2005, it posted net profit of 2.2 billion euros; in 2013, 5.34 billion euros. Finally, in 2005 it obtained earnings per share of 4.4 euros; in 2013, 8.10 euros. We are value investors, but there's no reason to turn our noses up at growth when the market doesn't make us pay for it.

Source: Morgan Stanley.

To conclude, the investment in BMW over 2005–2014 was a classic case of the right type of value investment. It's a perfect embodiment of all the virtues of the ‘approach’:

- Ridiculous market prices compared with correct valuation.

March 2009: Price: €11. Valuation: €100.

- Mr Market had lost his head in the middle of a crisis.

Depressed at a time of maximum volatility, he failed to discriminate between companies, senselessly obliterating everyone. BMW was lumped in with banks and real-estate companies, disproportionately damaging its share price.

- Mr Market is inefficient in the short term (2009 Price: €11) and efficient in the long term (2015 price: €70).

- The right mix of ability and value investor personality type led to a good result. In-depth study of the company to determine the right valuation (€100); conviction and courage to swim against the tide (buying when everyone else is selling); maintaining conviction over time (buying at the low point up to the maximum limit); and finally, patience (four to five years of waiting).

- Getting the valuation right is key. First we study the company and only then do we look at the share price. If the company has been properly assessed and the valuation is correct, then the investment will be profitable provided we are patient. Time plays in our favour.

- BMW is the ideal type of company for a value investor: sound company; family owned; cash-rich; no debt; powerful brand; subject to certain consumer cycle; durable; natural growth potential (China); focused on what it does well; and in 2009, an absolute bargain!

- All of this produced a superb result: profit of 300% over four years. Minimum price 2009: €11/Average purchase price 2009–2011: €20/2014 Sale price: €60.