CHAPTER 9

The Irrational Investor Lurking Within Us All

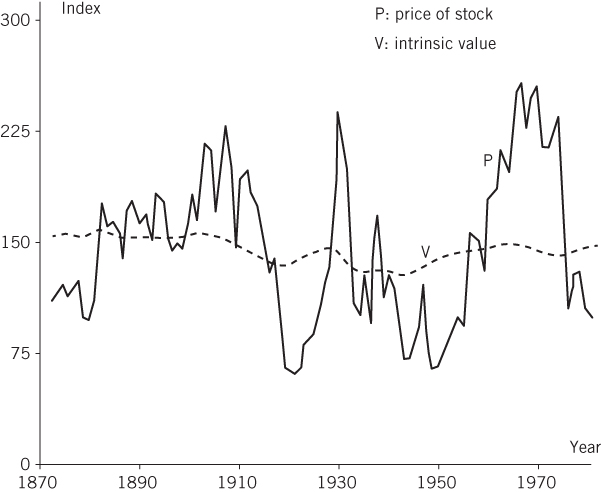

Yes, all of us. Investors, fund managers, even myself; we are all prone to behave irrationally to a greater or lesser degree. We have pretty clear objectives, such as maintaining the purchasing power of our savings, but we're incapable of making rational use of the tools that help us to achieve them. Historically, our irrational behaviour has led to volatility that has little to do with the performance of underlying assets, especially at turning points in the markets.

Funnily enough, in our ‘business’ the customer isn't always right: they invest at the top and sell at the bottom, hampering their ability to obtain returns, which tend to underperform the market average over the long run. This isn't just an opinion. Look no further than mutual fund inflows and outflows.

The goal of this chapter is to get to know ourselves better, with the aim of constraining our dark and crazy side, which drives us to act without thinking, or worse still, to do something which runs contrary to our interests.

- Why do we still believe that fixed income is safer than equities, despite all the evidence to the contrary?

- Why do some investment strategies systematically obtain better results? Why don't we make the most of them?

- Why do some fund managers repeatedly outperform the market?

Responding to these questions requires us to review the research carried out by psychologists and economists, which over the last 50 years has paid particular attention to our irrational behaviour, reaching conclusions relevant to economics and investment, which are our main areas of interest here.

It will come as no surprise to followers of the Austrian School that human beings are not always rational. Although it's true that when we are moved to act it is because we have certain end goals, which – like them or not – are always rational (otherwise we wouldn't act). It's equally true that we don't always choose the best means or apply them appropriately.1

Our goal might be to maximise our long-term savings or donate our wealth to people in need, but regardless of the objective, we need to use the right means to make it happen. We won't be able to maximise our savings by donating them to third parties or consciously investing in assets that don't deliver. That's what's irrational.

Before von Mises, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk explored the topic of irrationality, even though he was an economist and not a psychologist. He was particularly interested in the study of time preference and the errors associated with it, such as the excessive weight that we assign to the present or the time inconsistency of elections.

His interest theory was based on the fact that we assign more value to current goods than future goods, but in doing so we systematically underestimate our future needs and the means for satisfying them.2

He puts this down to three factors: poor planning of our future needs; a lack of willpower; and the uncertainty and brevity of human life. Each factor will weigh differently on each person and will vary over time.

Von Böhm-Bawerk was the first to analyse our time valuation ‘errors’ by citing psychological factors, which result in a myopic overvaluation of the present relative to the future and inconsistencies such as assigning a different value to the same time interval at different moments: we assign a lot more value to receiving something today instead of within a year, rather than between receiving it in five or six years' time. In both cases the difference is one year, but our assessment is different.

Twentieth-century researchers studied irrationality in much greater detail. The origins of our problems are to be found in the conflict between our emotional and rational sides,3 especially when our emotional response unduly outweighs the rational side. As popularised by Kahneman, we have two systems, which we will denote 1 and 2. System 1 operates quickly and automatically, almost effortlessly and without any real sense of control. System 2 pays attention to mental activities which require effort and involve complex calculations.

These systems are very well known to psychologists and we all believe that we act in mode 2, the conscious system, choosing freely and rationally. But that's not the case. System 1, the emotional side, is in the driving seat much more often than we think.

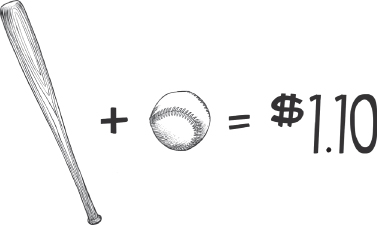

Take, for example, a classic problem to be resolved by intuition:

- A baseball bat and ball cost a total of $1.10. The bat costs a dollar more than the ball.

- How much does the ball cost?

The intuitive response is $0.10 but it's wrong, otherwise the bat would cost $1.10 and the total would be $1.20. The right answer is $0.05. With a bit of effort, none of us have any problem in reaching the right answer, but we're prone to laziness and we let intuition lead us astray. Over 50% of Harvard, MIT, and Princeton students gave the wrong response to this question, and as many as 80% in less-well-known universities!

The issue is not that we're more or less intelligent, but that we let ourselves be carried away by our more primal impulses without applying our intelligence. We think we are aware of our actions, but frequently we're not. Behaving like this can have very negative financial consequences, so the goal here is to review the problem and find ways to minimise it.

WHY DON'T WE INVEST IN EQUITIES? AVERSION TO VOLATILITY

The first and perhaps most important rational shortcoming is our extreme aversion to risk – confused with volatility in this case – which prevents us from investing most of our savings in equities, which would be logical given the rationale and historical evidence set out in this book. It's true that savers in some Anglo-Saxon countries with a more developed financial culture don't behave this way, and allocate a significant part of their investment to real assets, especially equities, through their pension funds. However, this doesn't happen in most cases. In Spain, for example, the majority of savings go into real assets, but primarily of the bricks-and-mortar variety (78% of total assets).

This aversion to ‘risk’, essentially volatility, is the most costly error of them all – since it prevents us from taking the clear path to increasing the purchasing power of our savings while taking on a minimal amount of real risk.

The same happens even in the most financially developed economies. For example, according to a survey,4 only 17% of Americans consider equities when thinking about investing over 10 years with money they don't need. 27% prefer housing and 23% would rather hold liquidity. To put it starkly, more Americans prefer holding liquidity in the long run than shares. The results are similar to those shown in Chapter 5.

If we think logically and consider historic results this is absurd, but it's nonetheless true. Schlomo Benartzi and Richard Thaler5 provide two reasons for this aversion to risk.

(1) Investors abhor losses, putting excessive weight on not losing and doing so myopically, with particular aversion to short-term losses. The joy of a gain is shorter lived than the misery and discomfort of a loss. Furthermore, we give greater weight to effective losses than opportunity costs (foregone benefit). We don't worry about not winning, especially if we don't know that our neighbour has; what worries us is losing.6

Such aversion is closely related to what is known as ‘frame dependency’, which describes how we can end up taking different decisions depending on how the problem is presented to us. Here, the issue is focusing more on the effective loss than the foregone gain.

Consider the following example of risk aversion, which was studied by Kahneman and Tversky.7

We are given two options: (a) Accepting a certain loss of $7,500 or (b) A 75% probability of losing $10,000 and a 25% chance of not losing anything.

Both options have the same expected loss of $7,500, but most people choose option (b) because they clearly dislike losing. In option (a) the loss is certain, while in option (b) there's the possibility of not losing.

It may well be that our brain has not evolved as quickly as it should have done and we still attach excessive weight to losing, since the organisms that worry most about threats have a greater capacity to survive. Not only does this lead to a loss of earnings, but it also opens the door to the real possibility of being manipulated by ‘perverse’ advisors.

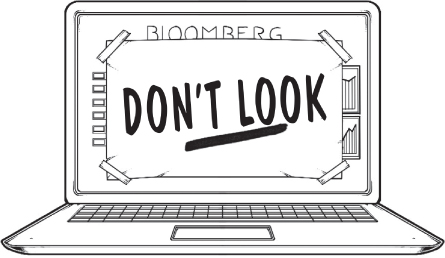

(2) We look too often at the results, which restricts us from having a long-term view. If we weren't as focused on them, our results would actually improve. Losses cause us more suffering than the joy we get from a similar amount of gain. When investing in equities, there are many days with losses, even though the final result is very positive over the long term. Therefore, by refraining from reviewing the results so frequently, we will be less exposed to losses and better able to tolerate volatility.

It's a challenge for us to ignore our emotional instincts and assign the right probabilities to the future results of different asset types. The combination of these two personality factors makes it very difficult to accept the volatility and consequent temporary losses associated with investing in equities.

Solving a problem requires us to be conscious of its existence and willing to get to the bottom of it. As soon as we recognise that we are not perfect and that we lack the necessary patience or mental composure, then knowledge should be our first source of support. By increasing our awareness of the underlying realities when we invest, we will help strengthen our conviction to commit a larger percentage of our savings to investing in shares. System 2 needs to be sufficiently well equipped to subdue system 1.

Admittedly, sometimes it's the very same ‘experts’ who end up making the most errors, but the more knowledge we apply to a decision, the greater peace of mind we will have. Patience can be cultivated.

Patience is key to the investment process, helping us to master our more myopic impulses. As such, anything that helps strengthen it is welcome. A practical tool is to take a systematic approach to investment. For example, investing a given amount at a certain frequency: for example, on the first day of each month, regardless of the circumstances. The amount and frequency are irrelevant, what matters is taking a firm and unshakeable decision to invest regularly. Taking this type of approach can often outperform intuition-based results, or at least equal them.8

Another useful approach is to space out how frequently we monitor our portfolios. If it's only once a year or once every three years, so much the better. It might seem like an abdication of responsibility, but if the strategy has been analysed and we are confident in it, then it needs to be left to do the work. I personally have no idea how much money I have invested in my funds. When I have some liquidity I invest that same day in the fund and I forget about it until I have more savings available. Sometimes I look at the monthly statement as a reminder, but other times I file them directly in the bin. The investors or clients who fare best when investing are those who, after having made a well-reasoned investment, refrain from constantly monitoring it.

As an investment professional, I'm obliged to track price movements on a daily basis, but as mentioned I wait until the market closes before firing up the computer and this is the only time in the day when I look at the day's trading. During the rest of the day I don't know what's going on with prices, unless the trading desk or someone in the team warn me that one of the stocks on our watch list is moving in a range that interests us and it becomes necessary to buy or sell. I don't have a Bloomberg terminal in my office; we have a shared one for the whole office.

Some well-known investors go even further and don't look at prices for weeks. Others will only let themselves execute orders after having slept on it. Any system which fits our needs is acceptable; what matters is that we aren't disturbed by day-to-day goings on.

A bit of knowledge and a few tricks up our sleeve can significantly improve our myopic aversion to risk and losses. One of my proudest achievements is having helped reduce the exposure to myopia of a large number of family, friends, and acquaintances, many of whom now realise that stock market volatility is a good thing for their long-term savings.

WHY DON'T WE INVEST USING PROVEN STRATEGIES, OR AT LEAST IN CHEAP STOCKS?

Mean reversion is the clearest conclusion that comes out of O'Shaughnessy's work analysing the performance of different strategies, as discussed in Chapter 6. Expensive stocks eventually become less expensive, posting bad results in the process, and cheap stocks return to average, improving their performance. If some readers remain unconvinced as to whether the market is capable of being efficient, it would seem clear that based on his analysis there is indeed an inefficiency to exploit.

Given the presence of such clear mean reversion in these strategies, it's surprising that they haven't been progressively corrected for by the market and that there's still scope for us to capitalise on them as investors. Once again the explanation lies within us all. The concept of mean reversion itself is very difficult to get a handle on. As Kahneman points out,9 Francis Galton developed the idea of mean regression five years after the appearance of the law of universal gravitation or differential calculus. It was an effort for him to digest the concept, and it continues to be a problem to this day.

The first problem is that we tend to extrapolate the future based on the past, particularly the recent past. We find it hard to believe that things will change. This is known as the ‘representativeness’ problem.10 But things change, and in a somewhat predictable fashion. Consider an example by Hersh Shefrin,11 which combines both the representativeness problem with mean reversion.

The aim is to predict the grades of university students, given that the average mark for students graduating from school is 3.08. If we have three new students in the university with average school grades of 2.20, 3.00, and 3.80, and we carry out a survey asking what their university grades are going to be, the forecast for the three students is 2.03, 2.77, and 3.46, respectively.

In reality, they obtain grades of 2.70, 2.93, and 3.30. In other words: one tends to think that the bad students will remain bad and the good will stay good. This is true to some extent, but the reality is that there is strong regression to the mean, which is not fully reflected in these forecasts.

| School Grades | Predicted University Grades | Actual University Grades |

| 2.20 | 2.03 | 2.70 |

| 3.00 | 2.77 | 2.93 |

| 3.80 | 3.46 | 3.30 |

Source: Shefrin (2000).

A particularly interesting instance of mean reversion can be found when looking at the quality of company management. Well-managed companies tend to perform worse in the future and their high returns on capital prove difficult to sustain. In Philip Rosenzweig's book The Halo Effect,12 he explains that the story that is told about the success of a company or the impact of its CEO can be very plausible, but more often than not it's come down to luck, which will then revert to the mean.

The same is true of money managers, who might have enjoyed a good ‘run’ that's not sustainable in the future. This is why it's vital to analyse their very long-term track record in detail, as well as their philosophy on life and investment. It's not enough to extrapolate from the past.

The second problem arises from the difficulty in going against the prevailing opinion around us: it's very hard to separate from the herd. Once again our prehistoric ancestors are tugging at us: historically, it's generally not been a good approach to leave the group to hunt or live alone; the group is usually right, or at least safer. Circumstances have changed more rapidly than our brains.13 In fact, when we feel excluded from the group it activates the same part of the brain as when we experience physical pain. It feels painful outside the pack!14

James Montier15 provides a famous example from Solomon Asch in 1951. If we are asked which of the three lines on the right (above) is the same as the left line, then the answer is obvious. But if we ask a group of at least three people and the other three people who are taking part in the research don't know the subject who is participating in the test, and they respond incorrectly, then the subject will respond in line with the majority on a third of occasions! And if there are various rounds, in at least one of the rounds, three-quarters of us will go with the majority view!

When we buy stock that nobody wants or a group of shares with a low P/E ratio, we are forcing ourselves to do something that feels counterintuitive. We might fully agree on the need to buy cheap stock, convinced that the strategy works, but when we hear the names of the companies we suddenly feel extremely giddy, and we grasp at a thousand excuses not to buy. Nobody is buying them and it's almost painful to do so…

A way to get around this is by committing to act upfront, applying the same approach as to overcoming our aversion to losing money (with the obvious drawback that we can always back out of it, meaning this strategy won't work). As previously mentioned, it's almost a semi-automatic reflex action for us to always sell when a stock goes up in price and buy when it falls. We look at the cause of the movement and if we think it's exaggerated, as is often the case, we act. When we sell on the rise, we sometimes refer to it as being fooled by randomness – in reference to Nassim Nicholas Taleb and his book Fooled by Randomness16 – because who knows whether we have just hit a lucky break and, as such, the simple fact of a rising price reduces the chances of this continuing. Who knows whether what we are attributing to skill is no more than chance? As Taleb observes, we tend to confuse judgement with luck. A possible solution to this is to assume that luck always plays a part in our success, spurring us to automatically act before it runs out.

The third factor is the point of reference. We have a tendency to immediately take the current price as our point of reference. If Telefónica is trading at 12 euros, we find it hard to think that it's worth 30 or five euros. This is a very common error among stock market analysts, who find it impossible to analyse Telefónica and reach a conclusion that while trading at 12 its intrinsic value is 20 euros. They will normally say 13.5 or 10 euros, because it's difficult to distance oneself from the current reference point (12 euros in this case).

Funnily enough, this seemingly illogical conduct contains elements of both the emotional system, 1, and the rational system, 2.17 We are indeed able to make a clear and conscious attempt to break from the reference point, but it continues to hold some sway over the result. Some investors get around the problem by first doing the analysis and valuation before then looking at the price. This makes it easier to avoid reference points.

These three traits – extrapolating, herd mentality, and reference points – get in the way of following proven investment strategies or buying stock when they are cheap. Once again the solution to mitigating problems which emerge from emotional baggage when making decisions is to be aware of the problem, knowing it can help to have in-depth understanding of the underlying reality – in this case financial – as well as implementing reflex or semi-automatic investment systems which improve our investment process.

But that's not the end of our problems, our mind can still play tricks on us. Other illogical behaviour can also hamper our ability to take decisions.

Sometimes we are caught in the trap of making rapid decisions on the basis of little evidence, overlooking the need for deeper analysis. As Kahneman18 explains, we are more attracted to a good, coherent story – or even the most recent one – than the full picture. The automatic emotional system comes to the fore.

The problem can be exacerbated further when we fall into the grips of an excess of confidence after an initial success in our endeavour or investment. This success drives us to double down, losing everything in the end. This is the biggest danger for the enthusiast investor, who gets carried away by gains during a bull market. This bull market is confused with a capacity or ability to invest, leading us to excessively increase the risk of our investments. This is not to deny that non-professionals can't be successful in investing, but it's worth being especially careful in the confusion created by a market with the wind in its sails.

It's extremely dangerous to think that we are more capable than our competitors and we are going to get it right all the time. Dangerous but all too common. We must fight to remain within our small circle of competence, as Buffett says. It's a small circle and we have to be conscious of just how small it is. We can gradually build it up over time, but there will always be a line we shouldn't cross.

A particularly disastrous illusion of control arises when we think that we can predict something: the economic or market outlook, or certain short-term market prices. I have already been pretty clear on this point, but it bears repeating that these things cannot be forecast. The best we can manage are some vague long-term estimates, which is distinct from forecasting, making investment decisions on this basis.

We invent the budgets for our company (I expect most readers can identify with this): we don't know how the markets are going to perform, nor what client inflows and outflows will look like, which are all crucial for determining income. Fortunately, expenses are somewhat easier to control, but they're not the key factor in our business. As a result, it's completely impossible to estimate the company's future results.

But what we do know is that we have a good management process in place and that income and profits will naturally follow. We don't set specific sales or profit targets to reach. This isn't applicable to all businesses, but I have already mentioned how the anxiety to meet objectives is one of the biggest errors in today's companies, since it can lead to myopic short-term decision-making. While sometimes targets can be a necessity, we prefer companies that don't have such targets and simply strive to do things well.

This relates to the delusion of thinking that we can explain what took place and that we know it was going to happen. We humans have a very strong tendency to change our understanding of the facts as they develop. If there's a strong fall, we will acknowledge that it was obvious and we'll forget that we had previously thought differently, and this applies across the board.

The somewhat contradictory tendency is to think that whatever's successful is well done. When a stock in our portfolio rises, we think that our analysis has been spot on, even though this increase may have been completely random. In fact, the result itself is not what matters, but rather that it's been accompanied by the right process. If the process is right and we can differentiate it from luck, then we will be able to replicate the success without making unnecessary errors.

Truthfully, the solution to problems generated be overconfidence is to be constantly humble, respecting our circle of competence. It's not usually very large, but this need not be a problem; size is not the key, what matters is respecting it and not venturing outside it.

THE ENDOWMENT EFFECT

Another important and very common problem arises from the special attachment that we have to our possessions, everything that we consider to be ours. We give extra value to an object if we already possess it and we struggle to separate ourselves from it. This becomes more of an issue when it concerns an investment error, since our attachment makes it hard to recognise the error and sell the stock, which probably requires us to accept some losses. I think it's the most frequent error that we have made as investors: Flag Telecom, Portugal Telecom, etc.

An example which is very close to home is Pescanova. At one point we had a very significant holding in this company in our Iberian portfolio, of 4%. Pescanova had a superb position in a growing sector, enjoying some barriers to entry, but every year debt went up and there were no clear signs of cash flow generation or treasury. We had a certain feeling that something was amiss, which is why we gradually unwound our position to 1.5% of the portfolio.

But we weren't able to go below 1.5%. The prices had dropped but we had a mental barrier which prevented us from fully offloading the stock, given the attachment you can build towards an investment. The logical thing would have been to completely sell the position and, clearly, we would have never bought in if we had needed to build a position from scratch at that time, but we were unable to let it go.

Furthermore, there was an added complication because when our investments are losing value, it tends to be a time for great opportunities. If an investment was attractive at a higher price, then it's going to be even more so at 20% lower prices. In such situations, being able to distinguish between strengthening a position, sitting tight, or selling can be one of the most challenging and important decisions we have to make. Our natural tendency is to increase the position, without pausing to think that there might be some major change affecting the investment outlook, with the risk of making an error.

And, in reality, facing up to an error is one of the hardest things for us to do. My experience tells me that the investment in terms of time, resources, and pride makes this one of the most difficult situations in which to do the right thing. You are always inclined to think that they are temporary problems which will resolve themselves. The ‘sunk costs of the decision’ are what makes it hard to change over time. There might also be some other factors at play, such as the desire to get something out of the weeks spent analysing the company, capitalising on it in some way, despite not being very clear on the specifics.

The way to mitigate the damage is relatively straightforward: we need to take the decision as if we didn't own any shares, as if it were the first time we were making a decision on the particular stock, forgetting about our current positon – would I buy shares if I began the analysis now? The solution is straightforward; the difficulty lies in cutting our losses, with all the corresponding implications.

The positive side of this endowment effect is that it skews us to what we know, and this is no bad thing during times when too many changes are made in search of new ideas. We know full well that limiting movements is a wise decision over the long term: better the devil you know…

TENDENCY TO CONFIRM WHAT WE ALREADY KNOW

Another danger that constantly stalks us is the tendency to look for evidence that supports our beliefs, avoiding conflicting opinions. It's an innate and almost automatic tendency which our emotional system uses to save time and energy. This can be beneficial when we're supporting our favourite football team or our political party (who we treat like a football team since they can't make errors), but it doesn't make sense when we want to make a rational decision (I don't know if voting is always very rational).

It's true that our beliefs can be very well founded and right (to boot!), which means it doesn't make much sense losing time paying attention to anything that has limited potential to contribute. But, either way, to avoid the danger of isolating ourselves in a bubble, the best solution is to listen to both sides of the debate, the arguments for buying and selling. We can even try to ‘intellectually demolish’ a company that appeals to us, to see if there is any substance to the arguments against. If we listen to conflicting opinions on a good investment we have found, we will at least be forewarned of where our competitive advantage lies when making the decision to invest.

THE INSTITUTIONS

Evidently, institutions and professionals suffer the same problem as any other investor, exacerbated by the fact that the committees overseeing investments seldom function very effectively.

A report by Bradley Jones of the International Monetary Fund,19 which analyses the behaviour of large-scale investors – endowments, sovereign funds, central banks, large pension funds – highlights the strong positive correlation that exists between the recent results obtained by an asset and investment decisions to buy what goes up in value. This correlation holds across all asset types, whether bonds, equities, or anything else. This might seem surprising given that the people responsible for managing these institutions are supposedly highly qualified and are meant to have a long-term perspective, but it is nonetheless the case.

The competitive pressures caused by the expectations of bosses, colleagues, and clients generate anxiety and an excessive focus on the short term. And this is even true for successful professionals. Such pressure generates fear of losing money, or even one's job.20

Many asset managers weave ‘stories’ to convince themselves and their clients and superiors, both regarding their investment philosophy as well as specific investments. These stories make it difficult to learn from errors, since they are rationalised in order to confirm the path that has been taken. Others try to lay the blame at the door of the companies they invest in – despite having claimed to be able to correctly evaluate them – or the brokers who have helped in the decision, without taking their own responsibility. No one faces up to their own mistakes.

Perhaps the best approach is to have a frank and healthy relationship with oneself, ones clients and bosses: investing time in educating them and not yielding to their pressure.

Furthermore, in investment committees, group thinking (group feeling as Tuckett calls it) also comes into play, which increases our dependency on others – with a strong tendency to conform to the group and avoid confrontation. James Surowiecki, in his book The Wisdom of Crowds,21 explains how group decisions prove to be right more often than individual decisions, but this only applies to decisions made by groups formed of different profiles, who are willing to voice their opinions. If this is not the case, we face the risk of group thinking.

Apart from attempting to incorporate a diverse range of views within the group, one way to reduce the risk is for each committee member to write down their opinion before anyone speaks. An alternative is to set incentives based on group results, which is the system that we have always applied.

Another inherent problem is the penchant for wanting to act, to do something, or to appear as though we're doing something, despite the fact that the best thing may well be doing nothing, letting the established strategy run its course. This happens more frequently in institutions, because the professionals who manage them are paid according to their results, and when they aren't up to scratch, they have the urge to explain that they have already taken steps to correct the problem by doing something.

INFORMATION OVERLOAD AND OTHER PROBLEMS

The amount of information we are exposed to has increased exponentially over time. When I started working in 1990 we had to write to companies so they would send us their annual reports, or physically go to the paper records at the CNMV, in order to be able to analyse their results. Nowadays we have all of this information on our computer or mobile at the touch of a button.

Although this might seem like an advantage, it can lead to us being exposed to an overdose of data and opinions that we don't need. Determining what's important isn't easy, but broadly speaking there are a few ways to separate the wheat from the chaff. 90% of the information that we receive on a daily basis from the media, for example, is background noise. That's why I recommend limiting our exposure to it as much as possible; as already mentioned, I haven't been regularly watching the television news or reading the general press for some 15 years now. It's enough to read a bit of economics and specialist news.

By the same token, while the Internet offers us an infinite array of information, it's also a source of infinite distraction. A few years back Nicholas Carr explained in his book The Shallows22 that it is incredibly difficult for us to concentrate when reading information online because we are continually being interrupted by distractions, limiting our ability to concentrate, which weakens over time. It's therefore vital to find peaceful moments to read and think, if necessary, physically secluding ourselves.

Moreover, I can't emphasise enough how overwhelmed I am by the negative slant on all the information we receive. Nobody could care less about a family calmly going about its evening meal. This leads us to constantly have a distorted view of the world. For example, in the last 25 years global growth has ticked along at 3–4% per year, with more than one billion people coming out of poverty; similarly, as Steven Pinker points out, violence is at its lowest level since mankind came out of the jungle, but nobody would believe this based on the information beamed to us on a daily basis.23

Matt Ridley24 provides a plausible explanation for this negativity, related to an evolving perspective of reality: all the many good things that have happened over the course of our evolution – economic growth, increasing life expectancy, reforestation in the developed world, reduction in inequality, practical elimination of hunger, etc. – haven't been planned by anyone; we have built them together, slowly but without stopping. This is apparently of absolutely no interest. We only want to know about wars, revolutions, homicides, etc., events which normally have much clearer protagonists than more positive developments.

Such negativity is just another way of expressing our aversion to risk, and is also an inherent part of our nature, since it has produced good results as we have evolved. In marital relationships, for example, doing something bad can only be compensated by doing five good deeds, or when we analyse somebody's character, a murder is only compensated by 25 heroic feats.25 The media make the most of the impact that this negativity has on our emotions to vie for our attention.

When facing information overload, in countless situations it has been proven that better decisions are made with less information, since in reality we are making the same error as when we are looking at market movements too frequently, which drives us to act when we shouldn't.

Nonetheless, as before, there are approaches which can help improve results in the face of excessive information. One option would be to stick to the same framework for reading (when reading something new, we have to leave what we were previously reading, so as to discourage ourselves from flitting around) or to only make active searches (inspired by our own ideas), avoiding the excessive influence of social networks or other supposed aides.

Taking decisions with small samples, without a suitable statistical calculation, is a problem that we have already cited. Confusing the anecdote with evidence is natural and commonplace, but it still remains a source of rash errors. More in-depth study is required to avoid falling into this type of error.

CONCLUSION

There can be no doubt that our emotional side makes it difficult for us to make the right investment decisions (as in all aspects of life). Overcoming this requires us to make an effort to better understand our flaws and correct them. It's not enough to perform a good competitive and financial analysis, something more is required. Summarising the key points described in this chapter, we can conclude that a proper investment decision should fulfil the following steps:

- Recognising that there is a problem: sometimes emotions lead us to take unreasonable decisions to achieve our desired goals and it's important to confront them.

- Analysing the content of the emotional shortcomings which we bring to decision-making. Proposing measures to take.

- Deepening our knowledge of the investment process through the experiences of other investors.

- Establishing simple and almost automatic mechanisms in this investment approach to minimise our emotional bias. An additional example which I have already mentioned tangentially, and which I use personally, is investing in funds the same day I have money available, doing so automatically and without thinking about what the market is going to do next.

- Analysing where we add value compared with other investors before taking a final investment decision. Normally it's not about being more intelligent, but has more to do with having a better understanding of ourselves, which translates into virtues such as patience and, in general, emotional resilience.

Our emotions are the main hindrance to obtaining good results from our investments. This is why it's important to dedicate the necessary time to understanding our weaknesses. Otherwise, there's no point investing since the results will be mediocre.

But there are reasons for optimism: we can learn from our errors. I did so with Nissan and subsequent errors, and we can learn to overcome our shortcomings. I know of countless people who, equipped with the right knowledge and following the example of other investors, have learnt to tolerate market movements and take the right approach to investing.

On this basis, and to finish, we can now sketch out some of the attributes of an ideal investor: somebody who is patient, invests over the long term, enjoying the journey and focusing less on the results, who doesn't get carried away by emotions, with strong convictions but willing to learn. None of us will ever fully become this investor, but it's worth making a continual effort to try and get as close as we can…