Chapter 10

Estimated Taxes, Self-Employment Taxes, and Other Common Forms

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Keeping up with estimated taxes

Keeping up with estimated taxes

![]() Withholding taxes from your employees

Withholding taxes from your employees

![]() Paying self-employment taxes

Paying self-employment taxes

![]() Using health savings accounts

Using health savings accounts

If you’re self-employed or running a small business, you have plenty to keep you busy each day, week, month, and year. Adding employees to the mix increases the complexity of what you’re doing.

For tax purposes, when you’re running your own show, you need to submit estimated income taxes each quarter during the year. When you hire employees, you need to submit the taxes that you’re required to withhold from their paychecks. This chapter tackles both of these issues.

Likewise, when it comes time to file your annual income tax return, you need to file forms to calculate your self-employment taxes (for Social Security and Medicare, for example). And you may want to contribute to a health savings account (HSA) for yourself, your employees, or simply to allow your employees to tap into this valuable benefit. Both of these topics are addressed here as well.

Form 1040-ES: Estimated Tax for Individuals

The U.S. tax system actually has a simple rule that most people don’t think about: It’s a pay-as-you-owe system, not a pay-at-the-end-of-the-year one. That’s why withholdings (having your taxes deducted from your paycheck and sent directly to the government) are great — what you don’t see, you don’t miss, and your tax payments are periodically withheld and submitted for you throughout the tax year.

If you’re self-employed or have taxable income, such as retirement benefits, that isn’t subject to withholding, you need to make quarterly estimated tax payments on Form 1040-ES (which you can find at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1040es.pdf).

You can avoid paying a penalty on tax underpayments if you follow these guidelines: You must pay in at least 90 percent of your current year’s tax, either in withholdings or in estimated tax payments, as you earn your income, or you can use the safe harbor method (see the next section).

Comparing the safe harbor method to the 90 percent rule

If your income isn’t constant or regular, you may choose to follow the so-called safe harbor rule and pay 100 percent of last year’s tax on an equal and regular basis during this current tax year. This method is simpler than it sounds. If, for example, you have a $3,000 tax liability showing on your most recent year’s Form 1040, you may make four quarterly payments of $750 during this current tax year. Provided that you do that, you won’t owe any penalty for a current year tax underpayment, even if your current year’s tax liability is substantially more — such as $15,000.

Because the safe harbor rule is so easy, you can simply choose to only use that when calculating your estimated taxes. Note, though, you do still have to pay the balance of tax due by the return filing date (April 15) to avoid late payment penalties and interest.

In comparison to the safe harbor rule, the 90 percent rule is tricky to calculate. In paying 90 percent of your current year’s tax, you need to adjust your payment amounts every quarter during the year that your income rises or falls. Using this method leads to increased paperwork. Still, because it’s one of your tax payment options, I explain how to calculate your estimated taxes using the 90 percent rule in the following section.

Completing and filing your Form 1040-ES

You need to accompany your estimated tax payments with Form 1040-ES (payment voucher), “Estimated Tax for Individuals.” This small form requires only your name, address, Social Security number, and the amount that you’re paying. For your current year estimated federal income tax payments, make sure that you use the current tax year’s 1040-ES.

When mailing in payment with your form 1040-ES, make your checks payable to the “United States Treasury,” making sure your name, Social Security number, and the words “2019 Form 1040-ES” (or whatever the current tax year is) are clearly written on the face of the check, and then mail to the relevant address listed in the Form 1040-ES booklet.

If you’re not sure how much you need to pay in estimates, Form 1040-ES also contains instructions and a worksheet to help you calculate your current year’s estimated tax payments. If you’re using the safe harbor method to calculate your estimated tax requirements (see the preceding section) and you have nothing withheld from any source, you can skip the worksheet, take the total taxes from your last year’s Form 1040, divide it by 4, and drop that number into each of the vouchers. You’re done! Now you just need to remember to pay your quarterly bills.

If, on the other hand, some, but not all, of your income has taxes withheld on it or you want to only pay 90 percent of your current year’s tax liability upfront (maybe because your income this tax year is going to be considerably less than it was in the previous tax year), you have to complete the worksheet that comes in the Form 1040-ES packet to calculate your estimated payment amounts.

The Estimated Tax Worksheet contained in the Form 1040-ES packet is a preview of your upcoming year’s tax return, or what you think that tax return will show. On it you include your adjusted gross income (AGI), your deductions, whether you itemize or take the standard deduction, any credits you’re entitled to, and any additional taxes you may be subject to. The worksheet can help you calculate the minimum amount you must pay during the current tax year to avoid paying penalties and interest when it comes time to file your annual tax return.

Keeping Current on Your Employees’ (and Your Own) Tax Withholding

When you’re self-employed, you’re responsible for the accurate and timely filing of all your income taxes. Without an employer and a payroll department to handle the paperwork for withholding taxes on a regular schedule, you need to make estimated tax payments on a quarterly basis (I discuss how to do so earlier in this chapter).

When you have employees, you also need to withhold taxes on their incomes from each paycheck they receive. And you must make timely payments to the IRS and the appropriate state authorities.

In this section, I cover what you need to do for yourself and your employees.

Form W-4 for employee withholding

If an employee owes a bundle to the IRS when it comes time to complete his annual federal income tax return, chances are he isn’t withholding enough tax from his salary and regular paychecks. Unless that employee doesn’t mind paying a lot on April 15, he needs to adjust his withholding to avoid interest and penalties if he can’t pay what he owes when it’s due.

Tax withholding and filings for employees

In addition to federal and state income taxes, you must withhold and send in Social Security and any state or locally mandated payroll taxes. You must also annually issue W-2s for each employee and 1099-MISCs for each independent contractor paid $600 or more.

To discover all the rules and regulations of withholding and submitting taxes from employees’ paychecks, ask the IRS for Form 941, “Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return.” Once a year, you also need to complete Form 940, “Employer’s Annual Federal Unemployment (FUTA) Tax Return,” for unemployment insurance payments to the feds. Also check to see whether your state has its own annual or quarterly unemployment insurance reporting requirements. And, unless you’re lucky enough to live in a state with no income taxes, don’t forget to get your state’s estimated income tax package.

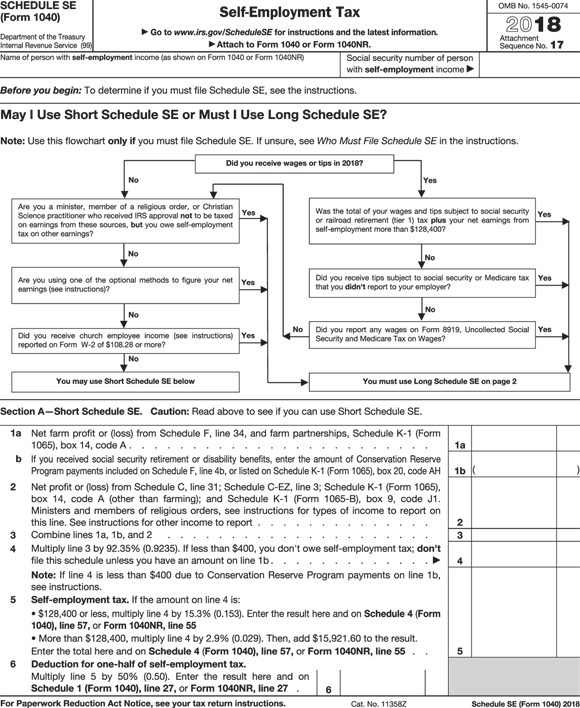

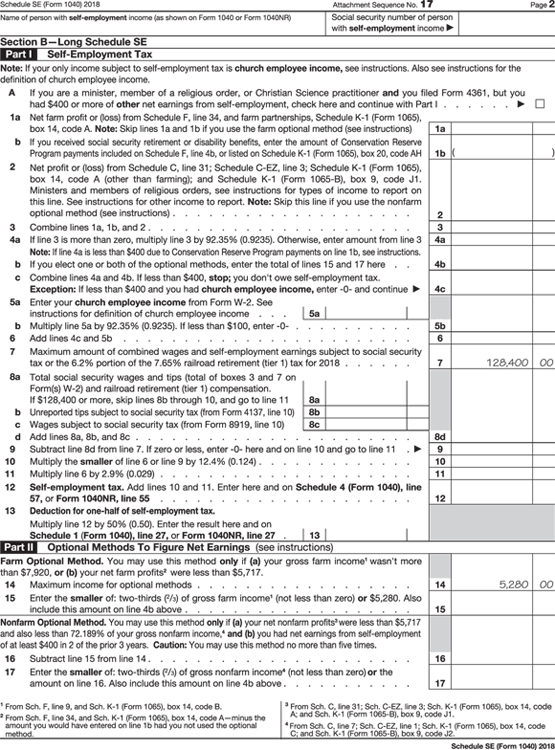

Schedule SE: Self-Employment Tax

If you earn part or all of your income from being self-employed, use Schedule SE to figure another tax that you owe — the Social Security tax and Medicare tax.

- The first $128,400 of your self-employment earnings is taxed at 12.4 percent (this is the Social Security tax part) for tax year 2018.

The Medicare tax doesn’t have any limit; it’s 2.9 percent of your total self-employment earnings. For amounts of $128,400 or less, the combined rate is 15.3 percent (adding the two taxes together), and for amounts above $128,400, the rate is 2.9 percent (see the exception in the following paragraph).

If your self-employment earnings are under $400, you aren’t subject to self-employment tax.

Note: Effective with tax year 2013, to help pay for federally mandated health insurance, higher income earners pay a greater Medicare tax rate. The additional Medicare tax amount is 0.9 percent on earned individual income of more than $200,000 (married couples filing jointly pay the additional tax on amounts above $250,000).

Your self-employment earnings may be your earnings reported on the following:

- Schedule C

- Schedule C-EZ; I discuss Schedules C and C-EZ in Chapter 8

- Schedule K-1, Form 1065 (box 14, code A) or Form 1065-B (box 9, code J1); use Form 1065-B if you’re a partner in a firm

- Schedule F or Schedule K-1, box 14, code A (Form 1065) if you’re a farmer

- Form 1040; your self-employment income that you reported as miscellaneous income (see Chapter 7 for more about Form 1040)

The following sections explain how to use Schedule SE to pay self-employment tax for Social Security and Medicare. Check out the 2018 version of this form in Figure 10-1 (and find the most recent version at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f1040sse.pdf).

Courtesy of the Internal Revenue Service

FIGURE 10-1: Schedule SE.

Choosing a version of Schedule SE: Short or long?

Wouldn’t it be nice if Schedule SE simply said, “If you’re self-employed, use this form to compute how much Social Security and Medicare tax you have to pay”? Paying this tax ensures that you’ll be entitled to Social Security and Medicare when you’re old and gray.

You have three choices when filling out this form:

- Section A — Short Schedule SE: This section is the shortest and easiest one to complete — six lines. But if you were also employed on a salaried basis and had Social Security tax withheld from your wages, you’ll pay more self-employment tax than required if you use the short schedule. Moonlighters beware.

Section B — Long Schedule SE: Use this part of the form if you received wages and are self-employed on the side. Suppose that you have wages of $40,000 and have $90,000 in earnings from your own small business. If you use the Short Schedule SE, you’ll end up paying Social Security tax on $145,000 when the maximum amount of combined earnings that you’re required to pay on is only $128,400. You pay Medicare tax, however, on the entire $145,000.

This section isn’t all that formidable. Make use of it so you don’t end up paying more Social Security tax than you have to.

This section isn’t all that formidable. Make use of it so you don’t end up paying more Social Security tax than you have to.- Part II — Optional methods to figure net earnings: If your self-employment earnings are less than $5,280 (for 2018), you can elect to pay Social Security tax on at least $5,280, so you’ll build up Social Security (and Medicare) credit for when you reach retirement age. You may do this for up to five years.

Half of your self-employment tax is deductible. Complete Schedule SE and note the following: The amount on line 5 of Schedule SE is the amount of tax that you have to pay (on the long form, it’s line 12); you carry it over to Form 1040 (line 56) and add it to your income tax that’s due. Enter half of what you have to pay — the amount on line 6 of Schedule SE (that’s line 13 of the long form) — on Form 1040 (line 27).

Completing the Short Schedule SE

Here’s the lowdown on completing Section A — Short Schedule SE:

- Line 1: If you’re not a farmer, you can skip this line. If farming is your game, enter the amount from line 34 of Schedule F or box 14, Code A, Form 1065, Schedule K-1 for farm partnerships.

Line 2: Enter the total of the amounts from line 31, Schedule C (line 3, Schedule C-EZ) and box 9, Code J1, Form 1065-B, Schedule K-1 (for partnerships). This is how each partner pays his or her Social Security and Medicare tax. You may also have to pay Social Security and Medicare tax on the miscellaneous income reported on line 21 of Form 1040. This would include income such as from directors’ fees, finders’ fees, and commissions.

Note: The following aren’t subject to self-employment tax: jury duty, notary public fees, forgiveness of a debt even if you owe tax on it, rental income, executor’s fees (only if you’re an ordinary person, and not an attorney, an accountant, or a banker, who may ordinarily act in this capacity), prizes and awards, lottery winnings, and gambling winnings — unless gambling is your occupation.

- Line 3: A breeze. Add lines 1 and 2.

- Line 4: Multiply line 3 by 92.35 percent (0.9235). Why? If you were employed, your employer would get to deduct its share of the Social Security tax that it would have to pay, and so do you.

Line 5: If line 4 is $128,400 or less (for tax year 2018), multiply line 4 by 15.3 percent (0.153) and enter that amount on line 56 of Form 1040. For example, if line 4 is $10,000, multiply it by 15.3 percent, and you get $1,530.

If line 4 is more than $128,400, multiply that amount by 2.9 percent (0.029) and add that amount to $15,922. (This is the maximum Social Security tax that you’re required to pay.) For example, if line 4 is $140,000, multiply that amount by 0.029 (2.9 percent is your Medicare tax), which comes to $4,060. Now add your Medicare tax ($4,060) to your Social Security tax ($15,922) for a grand total of $19,982. Enter $19,982 on line 56 of Form 1040. (Note: You get to use cents on Schedule SE if you so desire, but the IRS wants you to use the whole dollar method on Form 1040.)

- Line 6: Multiply line 5 by 50 percent (0.5). You can deduct this amount on line 27 of your 1040.

Form 8889: Health Savings Accounts (HSAs)

Health savings accounts (HSAs) allow people to put money away on a tax-advantaged basis to pay for healthcare-related expenses. This section explains how they work and the tax form — Form 8889 — that you must file with the IRS to claim an HSA deduction for contributions. (Check out the most recent version of this form at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f8889.pdf.)

Understanding how HSAs work and who can use them

Money contributed to an HSA is tax-deductible, and investment earnings compound without tax and aren’t taxed upon withdrawal so long as you use the funds to pay for eligible healthcare costs. So, unlike a retirement account, HSAs are actually triple tax-free!

The list of eligible expenses is generally quite broad — surprisingly so in fact. You can use HSA money to pay for out-of-pocket medical costs not covered by insurance, prescription drugs, dental care (including braces), vision care, vitamins, psychologist fees, and smoking cessation programs, among other expenses. IRS Publication 502 details permissible expenses.

Now, some folks think that it’s not worth contributing to an HSA if the money won’t be left in the account for long because of current medical expenses. I strongly disagree with this perspective because simply passing money through the account before paying medical expenses gains you the highly valuable upfront tax break. For example, suppose you have $1,000 in medical expenses currently (for an office visit and diagnostic test). By contributing the $1,000 to your HSA, if you’re in a moderate tax bracket, you could easily save yourself about $300 in income taxes.

Most insurance premiums aren’t eligible for being paid with HSA money, but some are. According to the IRS, you may “treat premiums for long-term care coverage, healthcare coverage while you receive unemployment benefits, or healthcare continuation coverage required under any federal law as qualified medical expenses for HSAs.” Also, if you have a balance in your account at age 65, you can use that money to reimburse for Medicare costs.

To be eligible to contribute to an HSA, you must participate in a high-deductible health plan that has a deductible of at least $1,350 for individuals and $2,700 for families for tax year 2018. The plan must have a maximum out-of-pocket limit of no more than $6,650 for individuals and $13,300 for families for 2018. Ask health insurers which policies they offer are HSA-compatible.

The maximum amount that you may contribute to an HSA is $3,450 for singles and $6,900 for families in 2018. (Those age 55 or older may make an additional $1,000 “catch-up contribution.”) All these dollar limits and amounts increase annually with the rate of medical inflation.

Employers with fewer than 50 employees can offer HSAs. Self-employed folks can use them as well. Anyone (so long as you aren’t covered by Medicare) who has an HAS-compatible policy may have an HSA.

Most HSAs require that some amount of money ($1,000, for example) be invested in a safe option like a money fund or savings account that is accessed with a debit card or checks that enable you to pay for medical expenses. Many HSAs offer a menu of investments — typically mutual funds. So, when comparing HSAs, you should compare the quality of those offerings.

Also, be sure to examine fees, which can really add up on some HSAs. In addition to the fees of the offered funds, beware of load fees and maintenance fees of about $5 per month (which may be waived for regular automatic investments or once you meet a certain minimum).

Investment companies have held off on offering HSAs themselves until they’re convinced that the market for them is large enough to make it worth their while. HSAs have also found themselves in the political cross hairs in Congressional debates and possible regulatory changes. So long as there’s a division in power in Congress, an erosion of HSA tax benefits is unlikely.

Completing Form 8889

Form 8889, “Health Savings Accounts,” is one of those IRS forms that looks much worse than it actually is, at least from the standpoint of the actual experience of most folks who get stuck filling it out. That said, for a minority of folks, Form 8889 can be cumbersome and time consuming.

If you’re contributing to an HSA, you generally need only concern yourself with Part I of the form. Here are the primary issues you need to address in this part of the form:

- Line 1: This is where you indicate whether your health insurance covers just you or your family.

- Line 2: Enter the amount of your HSA contributions (and those made on your behalf).

- Line 3: This is where you enter your maximum allowable HSA contribution. Note that the maximum is more for those age 55 and older at the end of the most recent tax year (see line 7).

- Line 4: If you have one of the older Archer MSAs, you need to enter the amount, if any, that you and your employer contributed to said account during the tax year, as that will reduce your allowable HSA contribution.

If you took any distributions from an HSA during the tax year, you address that in Part II of this form. You must track and report your distributions so that the IRS gets the taxes owed on them.

Finally, in Part III, if you failed to maintain a high-deductible health plan for the entire tax year, you may owe additional tax, which is determined and calculated here.

When you don’t pay your taxes on your income as you earn it, you may get hit with penalties and interest when you do pay them, on or before April 15 of the following year. Some small business owners are constantly taking current year’s cash flow to pay last year’s taxes and never quite catch up. In some cases, it can help to make payments more often than quarterly. Some business owners take a fixed percentage out of cash receipts and transfer that money to a separate account to make sure they have the money needed for their estimated tax payments.

When you don’t pay your taxes on your income as you earn it, you may get hit with penalties and interest when you do pay them, on or before April 15 of the following year. Some small business owners are constantly taking current year’s cash flow to pay last year’s taxes and never quite catch up. In some cases, it can help to make payments more often than quarterly. Some business owners take a fixed percentage out of cash receipts and transfer that money to a separate account to make sure they have the money needed for their estimated tax payments. For each tax year, quarterly estimated tax payments are due on April 15, June 15, and September 15 of the current calendar year and January 15 of the next calendar year. (If the 15th falls on a weekend, the actual due date is the next business day, which could be the 16th or 17th of a month.) If you file your completed current year’s tax return and pay any taxes due by January 31, you can choose not to pay your fourth quarter estimate (which is due January 15) without incurring any penalty.

For each tax year, quarterly estimated tax payments are due on April 15, June 15, and September 15 of the current calendar year and January 15 of the next calendar year. (If the 15th falls on a weekend, the actual due date is the next business day, which could be the 16th or 17th of a month.) If you file your completed current year’s tax return and pay any taxes due by January 31, you can choose not to pay your fourth quarter estimate (which is due January 15) without incurring any penalty.