Chapter 9

The Change Leader’s Role

What It Takes to Be a Great Change Leader

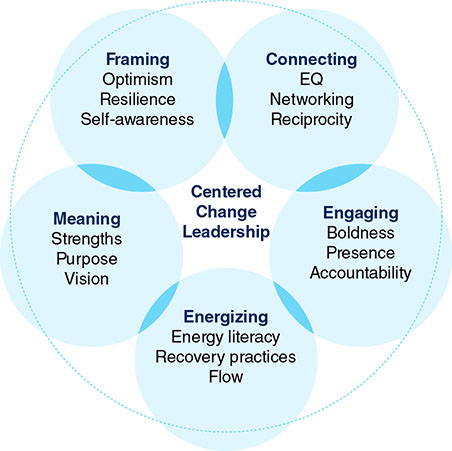

You’ve volunteered, or been voluntold, to lead a large-scale change program on behalf of your organization—congratulations! It’s no doubt a tribute to all you have accomplished in your career to date. If you’re like most newly appointed heads of large-scale change programs, you’ll be feeling a mix of excitement and anxiety about the challenges ahead. The excitement comes from the opportunity to make a difference on an even bigger stage, and to leave a legacy of forever having changed the trajectory of the organization (having “caterpillar to butterfly” impact!). The anxiety comes from the reality that expectations are extremely high, the spotlight will be intense, and the complexity of the job at hand is significant. What’s more, you are aware that huge bodies of research indicate you are very unlikely to be successful. We hope at this point in reading this book your excitement has been magnified and your anxiety diminished. You now know exactly what to do to beat the odds. You’ve got a clear, five-stage roadmap to help you stay focused on what matters for success on both the performance and health dimensions that you’ll need to manage. Knowing what to do, however, doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll be a great change leader. Having spent the last eight chapters talking about what you will be “doing,” we dedicate this chapter to how to “be” a great change leader. Before we dive in, let’s get clearer on the difference between the two. When you are in doing mode, by definition, the goal is to get things done. For example, in the Aspire stage, your thoughts and actions are focused on ensuring the long-term vision is crafted, rolled back to a mid-term aspiration, and that biases are guarded against in the process. You’re also getting the organization’s health checked, prompting the choice as to where to be exceptional and what broken practices need fixing. It’s a lot to do! In this mode you are continually monitoring and evaluating the current situation against the standard of what’s desired or required. When mismatches are found, your mind instructs you to take action to reduce the discrepancies. The doing mode is extremely important to drive progress on all the task-related work involved in making change happen. It is decidedly not helpful when it comes to dealing with your own emotional state as a change leader. And your emotional state matters. After all, at the end of the day you are not a human doing, you are a human being. As we discussed in the “Master Stroke” at the end of Chapter 4, by endlessly and relentlessly thinking about the problems, it’s all too easy to become characterized by blame, fatigue, and frustration—in particular given that not all the variables related to change program success can be controlled by you. We’ve met many a change leader who started optimistic, excited, and determined, only to find themselves 12 months into driving change feeling jaded, resigned to “best efforts” progress, and increasingly impatient for their next role. The being elements of change leadership are vital because they are what will keep you passionate about your work and satisfied with your life while leading the change. It enables you to avoid becoming narrowly preoccupied with closing the gap between what needs to be done and where things are today. Instead, it processes the current situation without losing the forest for the trees. You confidently tap into your intuition to avoid setbacks in complex situations. You see opportunities and learnings in the challenges that do emerge. You navigate ambiguity with creativity, and in turn create new possibilities for impact. We realize some of you will read the previous paragraph, perhaps even twice over, and still be scratching your head wondering what we’re getting at. We find the analogy to martial arts is instructive to make the distinction. Karate is what is known as a “hard” martial art—focused on blocking what your opponent is doing and punching and kicking back. It is based on resistance, and while helpful in some situations, it has the drawback of “what resists, persists.” Aikido, on the other hand, is a “soft” martial art. The goal is not to fight; the goal is to diffuse aggression by using the attacker’s energy and flowing with it, redirecting it to where it does no harm. It requires intuitive, split-second discernment of the direction of an incoming attack. It then requires creative twisting and turning in accordance with the opponent’s action to use the incoming momentum to off-balance and incapacitate the attacker as you remain fully centered. As a martial artist in the field of leading change, if you’ve read this far you know what it means to be a blackbelt at Karate (the Five Frames). In this chapter, you will learn the most important Aikido moves—moves we collectively describe as the art of “centered leadership.” Our research indicates there are five elements of “being” a centered change leader (Exhibit 9.1.) Exhibit 9.1 The Elements of Centered Leadership When combined, these elements give change leaders the resilience and emotional capacity to lead the “doing” of the Five Frames of Performance and Health. Our research shows that these elements of centered leadership are mutually reinforcing.1 Those who frequently practice all five feel passionate about their work, effective as leaders, and are satisfied with their lives (Exhibit 9.2.). Exhibit 9.2 Multiplying the Benefits Knowing that the power of these elements lies in their combination, we’ll now take a closer look at each one. In the centered leadership model, “meaning” relates to a change leader’s ability to motivate him or herself and others from within—grounded in a deep-seated belief that “what I/we are doing matters.” Research by leading thinkers such as Danah Zohar and Richard Barrett illuminates where this motivation comes from. It’s not about charisma and cheerleading—it’s about engaging fully in one’s own purpose and helping others connect with theirs.2 When people act out of a connection to their source of authentic purpose, they become more compelling as role models and more inspiring as communicators. Of course, the opposite is equally true: when you can’t help wondering, “Why am I doing this?” it’s hard to find the motivation to drive hard for results, and people around you perceive your lack of conviction and find the same. Change leaders who score high on meaning feel a deep personal commitment to the work they do and pursue their change goals with energy and enthusiasm. Of all the dimensions of centered leadership, meaning makes the greatest contribution to satisfaction with work and life. In fact, our research shows that its impact on overall life satisfaction is five times more powerful than that of any other dimension.3 This is confirmed by thinkers in the field of positive psychology (the branch of psychology that focuses not on treating mental illness but on making normal life more fulfilling) who have determined that having meaning is the foremost ingredient in the recipe for happiness.4 Psychologists Kennon Sheldon and Sonja Lyubomirsky, for example, show that meaningful work is the best way to increase overall happiness over the long term.5 The notion that leaders should be “meaning-makers” in the business lexicon is hardly news. Influential business thinker Gary Hamel urges modern managers to see themselves as “entrepreneurs of meaning.”6 Earlier in this book, we talked extensively about various techniques related to meaning-making. For example, tapping into the “lottery ticket effect” (increasing motivation for execution by involvement in crafting the solution that needs to be executed) and “five sources of meaning” (ensuring that your change narrative speaks to each). These, however, are all about the “doing” of meaning. At the “being” level, there are three keys to mastering meaning. The first involves recognizing and using your unique strengths. As with the bowling team experiment in Chapter 4, when we are building on strengths we are more likely to be motivated to excel than if we are solely focused on addressing weaknesses. Secondly, it involves having a strong sense of your leadership purpose. This isn’t “hitting the targets” (that’s the “doing” purpose); here we’re talking about the impact you want who you are as a leader to have on others. To determine this, in addition to your strengths, consider your past—when in your life have you felt deeply happy and fulfilled? What have you learned from challenges you’ve faced? Also consider what is your essence. What core qualities have always been true about you? What would you love to contribute before you die? What is the biggest possibility for the impact you’ll have as a human being? Then decide for yourself what you see the purpose is that sits beneath who you are as a leader in the workplace, regardless of role. What is the leadership legacy you want to leave when you retire (what do you aspire to characterizing the retirement speeches about you from colleagues, family, and friends)? And what does that mean for the leadership legacy you aspire to leave in the change leader role you are embarking on? Thirdly, mastering meaning involves giving voice to your leadership vision by sharing it with others who will surround you with helpful challenge and support. With these three things in place, you’ll find your actions and decisions are guided by a strong compass that keeps you grounded in what matters, whether in times of triumph or stress. In Chapter 4, we talked about the importance of “naming and reframing” underlying organizational mindsets to unlock improved organizational health and business performance. Similarly, as a change leader it’s vital to become aware of the otherwise subconscious frames you personally see the world and process your experiences through. The frames you choose can make a huge difference to personal and professional outcomes alike. While the exploration of an individual’s mindsets to uncover and shift performance-limiting or self-defeating viewpoints is intensely personal, there is one frame in particular that is of utmost importance to all change leaders: optimism. It’s easy to see how positive framing can improve change leadership capabilities. Pessimists tend to view negative situations as permanent, pervasive, and personal. This can limit their range of thinking, preventing them from seeing strategic options and rapidly draining energy in a downward spiral. Conversely, optimists view negative situations as temporary, specific, and externally caused. This helps them see the facts for what they are, identify new possibilities, and act swiftly. Imagine you’re giving a presentation to your bosses. They seem distracted, and halfway through, the most senior leader gets up and leaves the room. At the end of your presentation, you get a subdued response rather than the fanfare you’d secretly been hoping for. As you leave the room, what are the thoughts that run through your head? Do you wonder if your content or delivery were off the mark? Do you start to worry that management has lost confidence in you? Could your career be starting to spiral? If so, you have framed the situation through the lens of the pessimist. If you’re not careful, you’ll relentlessly dwell on the possible negatives to the extent that they ultimately paralyze your ability to take risks—something all change leaders must do to be effective. If you are an optimist, your mind goes to altogether different places. You wonder if the team may be grappling with an urgent problem that’s only just arisen? Perhaps your presentation came at a bad time, and yet they value you so much that they didn’t want to cancel your slot? You might even have taken the opportunity to stop and ask, “Should I carry on with this, or do you need to be somewhere else right now? And is there anything I can do to be helpful?” These optimistic lenses create resilience: the ability to absorb shocks, assess their implications, and respond effectively. Inevitably things won’t go according to plan in all cases, and when they go wrong, it’s the optimists who recover gracefully. Optimism correlates with success and much more: health and popularity, for starters. As former U.S. President Bill Clinton famously remarked, “No one in his right mind wants to be led by a pessimist.” Author Roald Dahl captures the notion in saying, “Those who don’t believe in magic will never find it.”7 Consider Thomas Edison’s response when, at age 67, his laboratory was destroyed by fire. A perennial optimist, what was his response to seeing his life’s work lay in ruins? “There’s great value in disaster,” he reflected, “All our mistakes are now burned and we can start anew.” Three weeks later, he produced his first phonograph. Or how about Steve Jobs’ view on getting fired from Apple in 1984, just eight years after he co-founded it? Instead of it being a career-ending blow as a pessimist would view it, he chose to believe, “Getting fired from Apple was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. The heaviness of being successful was replaced by the lightness of being a beginner again… it freed me to enter one of the most creative periods of my life.”8 Of course, not everyone is a born optimist. Many of us aren’t, and researchers say that as much as 50 percent of a person’s outlook is genetically determined. However, in Learned Optimism, Martin Seligman argues that optimism can be acquired.9 Pessimists can’t change their basic personality, but they can learn to apply the tools that optimists habitually use, without even realizing it, to put events and situations into their proper context. The techniques to do so are the same self-awareness techniques as those described in the “Make it Personal” section of Chapter 6. It starts by working through your personal “iceberg” (looking into the mindset-related drivers of your behavior) to explore in what situations you default to optimistic or pessimistic frames. From there, you explore the root-cause needs you are fulfilling in doing so (hopes and fears related to failure, rejection, hurt, being judged, being found out, not having all the answers, and so on). With this self-awareness, you then explore possibilities for how these can be fulfilled through an optimistic lens instead. To be clear, optimistic framing is very different than the optimism bias we discussed as something leaders should avoid in Chapter 3. This isn’t about persisting in trying to resolve an intractable problem long after it’s become time to move on. Nor is it the same as what people call “the power of positive thinking.” Research shows that talking yourself into a positive outlook has at best a temporary effect. Genuine optimists, on the other hand, tend to be realists. Perhaps surprisingly, they are more able to face the brutal facts than pessimists are. This dynamic is vividly illustrated in the “Stockdale paradox,” described by Jim Collins in his book Good to Great. Admiral Jim Stockdale was the highest-ranking U.S. military officer in the so-called “Hanoi Hilton” prisoner of war camp at the height of the Vietnam War. Imprisoned from 1965 to 1973, he was frequently tortured, and had no prisoners’ rights, no release date, and no certainty that he would ever see his family again. How did he survive? “I never doubted not only that I would get out, but also that I would prevail in the end and turn the experience into the defining event of my life … [But] you must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end—which you can never afford to lose—with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”10 Another mark of the centered change leader is the ability to forge relationships with influential people from different stakeholder groups. Such leaders build complex networks that both amplify their personal influence and accelerate their personal development because of the diversity of ideas and experiences that they encounter through contact with others. Psychology has long established that relationships are essential to our well-being. It turns out that they are just as important to our success. Research from Harvard professors Ronald Heifetz and Marty Linsky indicates that people who are thoughtful about personal relationships are more successful as change leaders.11 Similarly, management scholar Ernest O’Boyle and colleagues showed that individuals’ levels of emotional intelligence (EQ) has profound effects on performance, above and beyond those factors related to personality and IQ.12 Studies at PepsiCo confirm these conclusions. In comparable bottling plants, teams with the highest EQ performed 20 percent above the norm, while those with the lowest rating performed 20 percent below. Psychologist and science journalist Daniel Goleman popularized the concept of EQ in his book Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ. In it he reported his findings from analyzing the difference between “good” and “high” performers in thousands of positions in hundreds of companies. He found that 90 percent of the difference related to emotional intelligence—EQ, not IQ.13 Perhaps more importantly, he showed that EQ is learnable. If leaders reflect on the right topics and questions, they can improve their ability to connect with others at an emotional level and so adopt the relational styles that will achieve the best results. To be a great connector, our first suggestion to change leaders is that they invest time in building their EQ to best equip themselves for the role. Take the concept of trust, for example, which is fundamental to establishing strong relationships. If we asked you how trustworthy you are, it’s likely you’d respond with “very.” If we asked you the extent to which you embody the four elements of trust individually, however, you may gain some insight into how you can better connect with others. How reliable are you (you do what you say you’ll do)? How accepting are you (listening to and respecting others’ viewpoints empathetically and without personal judgement)? How open are you (giving and asking for input freely)? How congruent are you (saying and doing what you really feel and believe)? And if you were to answer these questions in the context of your behavior with your family versus at work, do the answers change? Why or why not, and does that synch up with the leadership legacy you want to leave that we discussed when talking about “meaning” a few sections earlier? Our second suggestion to change leaders is to be strategic about the networking they need to maximize success in their role, and to invest methodically in building that network. In doing so, they should be aware of their gender and other biases in thinking about the network they need. Researchers have shown that whereas women prefer to build a small number of deep relationships (helping to get “let me tell you how it really is” type of advice), men tend to build broader but shallower networks (helpful in providing a wide range of resources to expand knowledge and opportunities).14 Great change leaders have both kinds. When we advocate building a network, we aren’t just talking about one that consists of our peers or superiors in the organization hierarchy. We’re also thinking beyond the influence leader-types we discussed in Chapter 6. We believe you should follow networking consultant Carole Kammen’s advice to stress-test your network and ensure it provides a whole host of benefits: wisdom and experience, a sympathetic ear, challenges and shifts in perspective, help in navigating the social system, nonstop coaching, visionary inspiration, and sponsors who will pound the table for you. Sometimes these can take different forms than you’d expect. For example, when GE’s Jack Welch was looking for mentoring on how to use the internet effectively, he hit on the idea of “reverse mentoring”—asking two people under the age of 30 at GE to help him get up to speed.15 Finally, we encourage change leaders to think through how to ensure there is reciprocity in the relationships in their network—equal give and take. Why? As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt notes, “Relationships persist to the degree that both people involved believe that what they are getting out of the relationship is proportionate to what they put in.”16 Engaging is first about choosing to be fully present in all situations related to making the change happen. There’s no question in anyone’s mind that you’re in it to win it. Second, it’s about the willingness to be bold when needed. It’s the change leader who recognizes, in the words of Irish footballer Jim Goodwin, that “the impossible is often the untried.” Finally, it’s about taking accountability for positively influencing their own, their organization’s (team, peers, boss, employees), and their organization’s stakeholders’ experience of the change. This is the change leader who approaches work and life with the mindset of, “If it’s to be, it’s up to me.” On the other hand, people who are disengaged tend to be passive in their interactions, incremental in their actions, and feel that events are out of their control. Rather than trying to fix problems, they attribute blame. In our research on centered leadership, respondents who indicate they were poor at engaging—with risk, with fear, or even with opportunity—also lack confidence: only 13 percent thought they had the skills to lead change.17 Engagement differs from framing in that positive framing enables us to see an opportunity, while engagement gives us the courage to risk capturing it. Writing in 1951, the mountaineer and author W. H. Murray sums up one of the things that makes engaging so powerful: “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness… the moment one definitely commits oneself, then providence moves, too.” For him, engaging sets in motion a whole chain of events that “[raises] in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents, meetings, and material assistance which no man could have dreamt would have come his way.”18 So how can we expand our level of engagement? It helps if we have an elementary grasp of how the physiology of the brain governs our instinctive responses. Put simply, the brain consists of three parts. The first is the brain stem, which deals with basic functions such as breathing. The second is the limbic system, which regulates emotions. The third is the neocortex, which governs logical reasoning and creativity. Within the limbic system is an organ called the amygdala, whose function is to protect us from physical or emotional harm. As information about our surroundings enters our senses, the amygdala tests it on the way to the neocortex to determine whether we have time to think. If it detects a threat, it short-circuits our rational thought processes and prompts an immediate reaction. This process is often referred to as an “amygdala hijack”; we don’t choose the response, it simply happens to us. When we’re hijacked, our responses are quite primal—falling into the categories of fight, flight, or freeze. Let’s use some physical examples to bring these to life. Let’s say it’s April 1st, which in many Western cultures is known as April Fool’s day—a day where playing harmless practical jokes and spreading hoaxes is celebrated. You are on your guard with your coworkers who tend to be pranksters even on “normal” days. As you walk into your office you are pleased to see everything appears to be in order. You proceed to sit down on your office chair, not realizing that an air horn has been rigged beneath it to go off as soon as it bears your weight. As 130 decibels of sound is blown, what is your response? You instinctively leap away from the chair with a panicked scream, landing with muscles tense and heart racing. It’s only when you’re safely off the chair and the sound has stopped that your brain takes the time to work out what’s happened—and to notice your colleagues are laughing hysterically outside the glass walls of your office! So what just happened? After all, it’s very unlikely you are going to be in a life or death situation sitting on an office chair. Further, you were mentally on guard for a prank to happen today. Yet your amygdala was triggered, and your response was hijacked. There was nothing you could do about it. Thinking first and acting second could have ended in disaster, or so it seemed in the moment. You just experienced a flight response. Now, let’s say later that night you are home alone. As you walk through your dining room, you are startled by something you see in the corner of your eye, a movement of sorts. You find yourself instantly still and silent. You’re experiencing a primal freeze response that attempts to keep a potential predator unaware of your presence by blending in. You then regain your composure and assess the situation, only to realize the effect was caused by the reflection of headlights from cars on the street outside reflecting off of the new vase of flowers your coworkers had purchased for you as an apology for the earlier scare! Even though there is no danger, you’re now craving some company and decide to drive to a friend’s house. En route, someone rudely cuts you off on the freeway. You feel a surge of adrenalin and let out a string of expletives, offering hand gestures to suit. Welcome to the fight response! It’s clear from the examples above that our amygdala assumes the worst. This is generally not a big problem in life when it comes to our responses to potential physical threats, but it does become problematic in the workplace and other social interactions. Why? Recall that our amygdala doesn’t just protect us from physical pain, but also emotional hurt. For example, when a colleague says after a meeting, “I have some feedback for you,” many people go into fight mode and listen defensively. Others go into flight mode and avoid having the conversation. Still others freeze and hear the feedback but aren’t really listening. This can set off a downward spiral both internally (e.g., resentment, thoughts of revenge, writing people off) and externally (e.g., passive aggression, feigning agreement, an outright argument). There is a different response available that is vitally important for change leaders to master. Instead of the “reactive response” that lets instinct take over, a leader can choose a “creative response,” in which they take ownership of the situation, understand it more fully, and seek a win-win solution. Choosing the creative response starts with being aware of the physical cues that let you know a hijack is in process. These differ from individual to individual, but typical examples include sweaty palms, increased heart rate, butterflies, flushing/turning red, clenched jaw, and so on. As soon as you feel these coming on, the next step is to activate your neocortex by asking yourself a question. The most helpful questions involve taking personal accountability for the situation. Examples include: “What is my role in creating this?”; “What can I learn from this?”; “How can we both win in this situation?”; and “How can this situation bring us closer?”. To give your rational mind time to regain control, it’s often helpful to ask a question of the other party such as, “Tell me more” or “Help me understand further.” The folk wisdom of counting to 10 before reacting also applies, which effectively gives your neocortex a chance to process the situation at hand. Consider the e-mail that you read at 2 a.m. while exhausted after a tough day trying to get one of your initiative teams staffed that says, “Not only do I think Jane is too valuable in what she’s doing to go full time, but I’m also thinking we may want to revisit if the initiative is really necessary.” The reactive response would dash off an immediate response copying the senior sponsor of the initiative along the lines of, “Really? We agreed … This type of backtracking is exactly why … If you don’t … I’m copying … It’s unacceptable that … I expect …” and so on. A more creative response would be, “Thanks for getting back to me. I’m keen to understand more here—let’s get on the phone tomorrow,” followed by getting some rest and strategizing with the executive sponsor in advance of the call regarding how to get the leader back on board with the program. Change leaders can also take steps to eliminate unnecessary and unhelpful hijacks altogether. Doing so starts with taking time to understand one’s triggers (e.g., criticism, feeling judged, integrity questioned, credibility questioned, being interrupted, excessive details, unclear expectations). Once understood, exploring the root causes as to why these act as triggers can often reveal how formative experiences hardwired one’s amygdala to have disproportionate responses. This puts leaders at the point of choice as to whether they want experiences from deep in their past to affect how they think and respond in the present and to let go of the often irrational fears that are driving them. In doing so, they are effectively reprogramming their amygdala. Finally, there are also numerous tools from the field of mindfulness that are the equivalent of lifting weights for the muscle of managing one’s amygdala. Mindfulness is the basic human ability to be present, aware of our in-the-moment thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment, yet not overly reactive or overwhelmed by any of these things. By being fully present, one isn’t rehashing the past or worrying about the future. In this state, change leaders rarely get triggered, and when they do they are facile in ensuring it doesn’t lead to unintended consequences. There are numerous techniques to improve one’s mindfulness through quality sleep practices, meditation, mindful movement and eating practices, among many others. As mindfulness increases, reactive response patterns decrease—gone are experiences of withdrawing, justifying, attacking, staying quiet, punishing, swearing, avoiding, and resignation. Enter instead more experiences of feeling of being in control, confidence to achieve high aspirations, and willingness to take bold actions.19 We’ve already discussed in Chapter 6 how, at the organizational level, change programs need to generate more energy than they consume. The same is true at the individual level, in particular for the change leader and his or her team. This means systemically restoring their own energy levels and creating the conditions for others to do likewise. There are three ways we encourage change leaders to generate energy. The first is to heighten their energy literacy relating to what they personally find energy-generating and depleting. The second is to proactively build recovery practices into their daily routines. The third is to create the conditions for flow experiences to happen as often as possible. Energy literacy enables change leaders to manage their energy with as much or more rigor than they manage their time. Doing so has out-sized benefits, as well. Time is finite, so managing it is like dividing up a pie. But if you manage energy well, you generate more, and so the whole pie gets bigger.20 Life is full of things that generate and deplete our energy. Which is which, however, isn’t always obvious. The same activity can have different effects on different people. Take driving home at the end of the day. For some, it can be calming and restorative—a buffer between work and home that provides a space to detach and recover from the events of the day. For others, the same drive in the same car in the same traffic can be stressful and draining. Or take folding laundry. Some enjoy the feeling of warm clothing just out of the dryer, find comfort in the order they are creating and the feeling of “getting something done” that is tangible. Others couldn’t imagine a more mindless use of their time. Practically speaking, what energy literacy enables you to do is identify what generates and depletes your personal stocks of four types of energy: mental, emotional, spiritual, and physical. Armed with this knowledge, you can then adjust your days and weeks so that you don’t create energy troughs—long periods of time doing energy-depleting activities, after which you’re ready to give up. Instead, you can sequence activities so that your baseline energy levels are more moderated, with generators interspersed with the depleters. You can also delegate as many energy-depleting activities to others as possible. As per our driving home and folding laundry examples, for many of these activities there will be someone who finds them energy-generating, thereby creating an energy “win-win.” This can be done at work and at home. The next tool for energizing is creating recovery practices. It’s important to be aware that no one can stay in high-intensity work mode all the time. Consider a marathon runner. They don’t run marathons every day, and after every race they take time to recover then build up appropriately for the next one. Or take driving: you can’t just keep the pedal to the floor indefinitely or you’re only going to move forward until your fuel tank runs empty or your engine overheats. By stopping to refuel and routinely maintain the engine, you can go whatever distance you need to—and ultimately in less time than if you tried to go all the way at top speed but broke down along the way. The most successful change leaders formally structure time into their days, weeks, and months to restore and renew themselves in whatever ways work for them. This could be as simple as regularly going for a walk, spending time with friends, exercising, reading a book, meditating, getting enough sleep, stopping work to eat a nutritious meal, having technology-free time, or planning a vacation. Be warned: if you can’t oscillate between intensity and recovery, you’ll quickly find yourself moving from high-intensity positive emotion (peak performance) to high-intensity negative emotion (anger, frustration, impatience, stress). If you continue to ignore the advice to build in recovery time, be warned that it will be forced upon you in its negative form—burnout and depression. The third tool for energizing is to look for what psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi describes as flow experiences, when work becomes effortless and the concept of time seems to stand still.21 Athletes describe this feeling as being “in the zone”; musicians call it “in the groove.” Csíkszentmihályi studied thousands of subjects, from sculptors to factory workers, and asked them to record their feelings at intervals throughout the working day. When he correlated flow to performance, he found that individuals with frequent experiences of flow were more productive and derived greater satisfaction from their work. They also set themselves goals to increase their capabilities to meet greater challenges, thereby tapping into a seemingly limitless well of energy. In fact, their experience of flow was so pleasurable that they expressed a willingness to repeat flow-generating experiences, even if they were not being paid to do so! Sounds great, but how do you get into flow? According to Csíkszentmihályi, it happens when we set meaningful goals that challenge us and require all our skills (related very much to what we covered above in our discussion on meaning), when we give an effort our full attention and focus (as we covered in our discussion on engaging) and when we receive regular feedback so that we can fine-tune our efforts for the greatest possible impact (something our networks can help us with). But what if we do every one of these things and still fail in achieving the outcomes we strive for? If that happens, and there are sure to be times when it does, our ability to pick ourselves up off the floor, use the experience to learn and grow, and continue to build toward a positive future (as discussed in the framing section) is key. As such, this is where all of the elements of centered leadership come together and enable us to tap into all of our energy sources in every moment we spend leading change! ■ ■ ■ We realize that it will feel clichéd to many readers for us to close this chapter with the well-known quote from Shakepeare’s Hamlet, but it’s obviously the right question for you as a change leader: “To be, or not to be?” “To be” is to act out of a deep sense of meaning. It’s framing challenges as opportunities to learn and grow. It is connecting productively with a broad and deep network of important influencers. It’s engaging creatively, confidently, and proactively in the face of adversity versus being “hijacked” into fight, flight, or freeze responses. It’s systematically energizing yourself physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually throughout the journey. We hope that you can see the power and benefits of you “being” a great change leader, in addition to “doing” the right things to make change happen. We also encourage you to consider the power and benefits of all of the influence leaders also acting as centered leaders. And how about if 25 to 30 percent of the organization was characterized by centered change leadership? These aren’t rhetorical questions. In fact, the Personal Insight Workshops (PIWs) mentioned in Chapter 6 are designed to do precisely that. They can be used to build your skills and confidence so that you become a powerful role model in all the areas we’ve described. As such, we recommend that you, your team, and a cadre of influence leaders become the pilot group for the PIWs. Once you’ve been through it (and made it better through your feedback), it can then roll out to a critical mass. In practical terms, then, the work related to the “doing” and “being” aspects of change leadership are merged together in the Five Frames methodology—in very much the same way that performance and health become one in the process.Being a Centered Change Leader

Meaning

Framing

Connecting

Engaging

Energizing

Notes