Governance: Governance Planning for Continuity

Cornerstone Concept: Craft the Family's Governance Philosophy.

Preamble: Governing the growing family group, the heterogeneous ownership group, and the array of operating and investment entities requires planning and oversight. Members of the continuity model generation are good governance zealots.

The governance plan, for continuity modelers, really is the keystone in the arch of the canvas. As highlighted previously, this generation sees communication, education, accountability, and transparency as vital to any chance for continuity.

Governance Planning for Continuity I: Collecting and Collating Basic information

The first step here is the same as for the other plans: undertaking an honest evaluation. For some, this will involve diligent benchmarking to establish how others govern their family, their business, and their ownership groups. What this process will reveal is that governance is best understood along a continuum anchored at one end with “informal” and the other with “formal.” The mantra that most use when journeying along this continuum typically includes anchor comments such as (i) “What works for the current generation won't work for future generations”; (ii) “Let's act with a sense of urgency not a sense of panic”; and (iii) “Beware allowing the pendulum to swing too far in the opposite direction, as that will lead to over-governing.” Or as someone interpreted, “Don't hit a nut with a sledgehammer!”

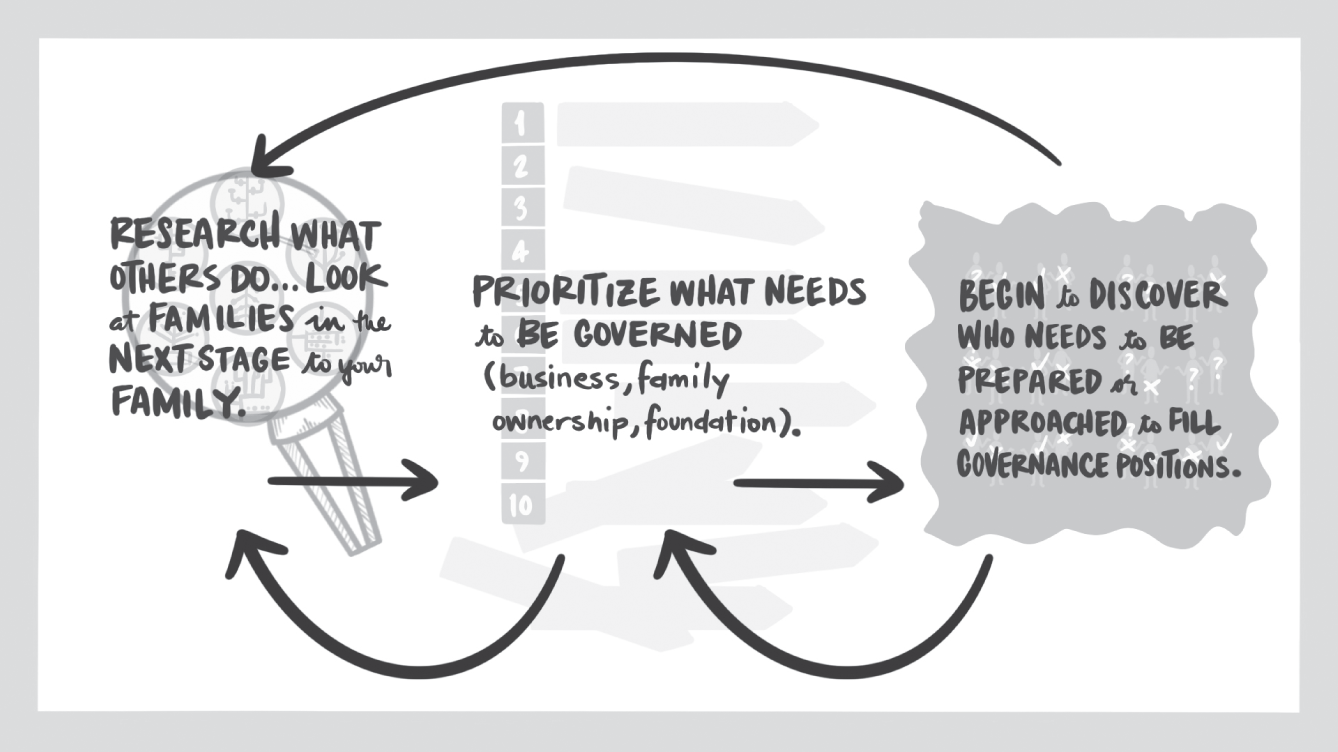

So, the first task is to know what you don't know. In other words, find out how others govern. The key here is to learn from those who are ahead of you in terms of governance planning, implementation, and functioning. In other words, a sibling partnership should be learning from a cousin consortium. A nascent cousin consortium should learn from a more mature governed family. This will illuminate that effective governance requires a relentless focus on process innovation.

Once in the governance planning lane, the second, usually concurrent, task is to establish what needs to be governed. Do not get too worked up over this. Everything is already governed, albeit in many cases, informally (and it works, to a degree). You are aiming to firmly establish structures and processes that, though they can and will need to be tweaked, will stand the test of time.

Next is deciding who is going to govern. A successful continuity model is predicated on looking forward, ensuring that the positions on various boards are always filled by the best qualified (Illustration 29).

While there are large numbers of books, articles, associations, courses, advisors, and experts to assist in creating governance protocols, the continuity model generation genuinely engages in understanding the governance landscape. This is not something they outsource. The constant question they ask, and others ask of them, is “Are we in good hands?” Put another way, can we trust those who are in decision-making roles in our companies and on our boards? This plan, likely, will ultimately dictate whether continuity will occur relatively seamlessly. These “governance ninjas” constantly seek information about how they can innovate to make governance structures stronger. It is not a set-and-forget approach. Like the other plans, a plan for the plan is required.

Illustration 29 THREE-STEP APPROACH PLAN FOR THE GOVERN-ANCE PLAN

The mantra that the continuity model generation lives by goes something like this: The aim of the game is to build trust within, between, and among a team of decision-making teams: within the different boards (business, family, ownership, foundation), between each of these in dyads, (business–family; business–ownership; business–foundation; family–ownership; family–foundation; ownership–foundation), and among the business, family, ownership, and foundation boards.

Governance Planning for Continuity II: Cornerstone Concept Equals Craft the Family's Governance Philosophy

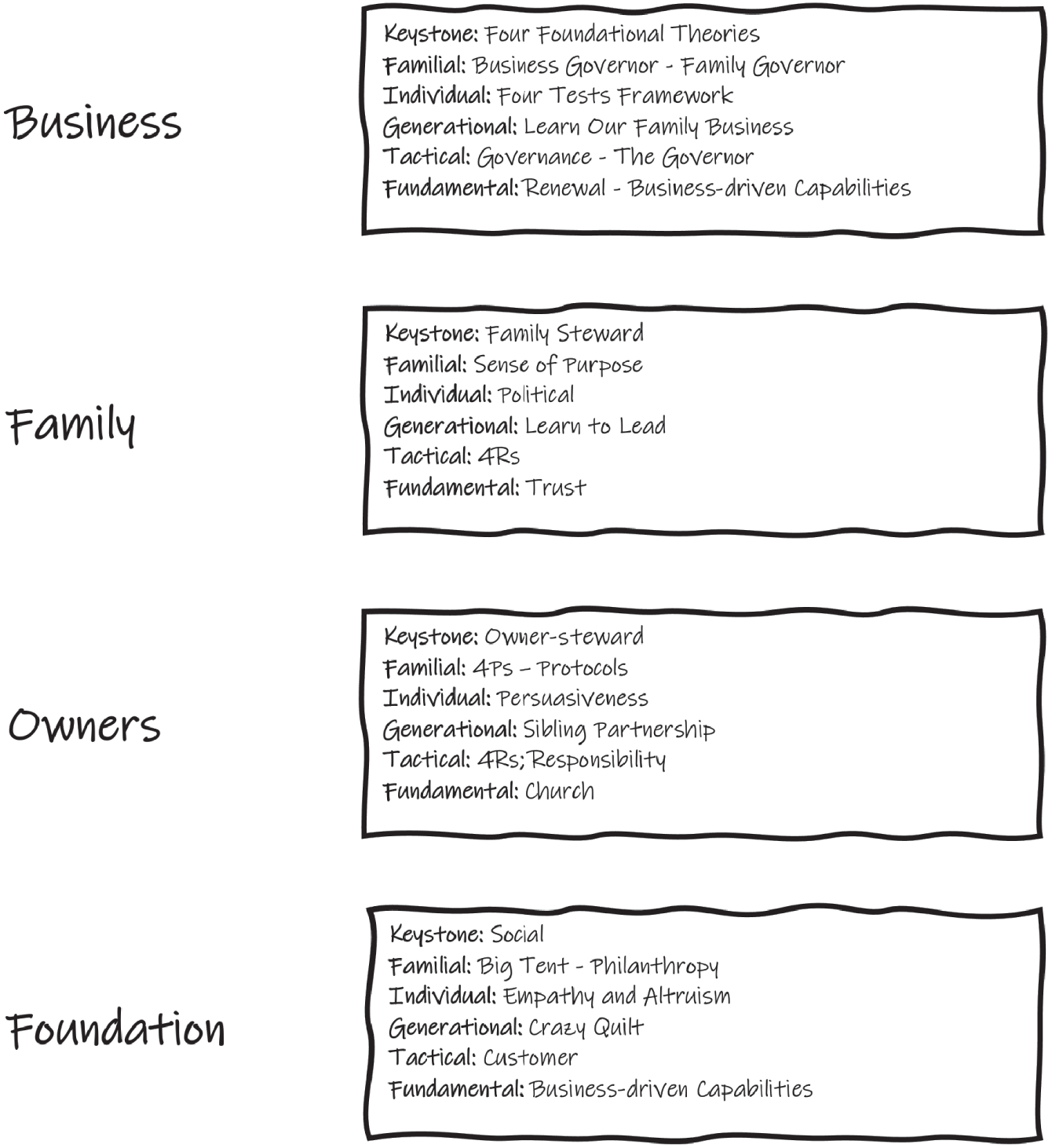

Following the template established in the previous planning processes, the overarching objective is to develop a governance planning process for continuity driven by the 21 frameworks. For this plan, we focus on how they apply to four entities that require governance: (i) the business, (ii) the family, (iii) the owners, and (iv) the foundation.

The first task is, again, to consider which of the 21 frameworks will assist with strategic population of the 4 entities. And once again, in the Illustrated Table 4 below I provide an example, with subsequent description of the rationales for including these items (Illustrated Table 4). Developing this section facilitated the opportunity to include a considerable amount of additional material, which may seem only loosely connected to the assigned framework. The idea is to assemble the pieces strategically to craft your own governance philosophy. The Continuity Model Generation considers governance the vehicle of continuity, and members are consummate learners of ways to improve related structures and processes. By now, the message to think broadly and deeply should be clear. Stretching the existing frameworks and complementing these with other concepts and thinking is not only encouraged but necessary.

Governance is a journey. When reviewing the example below, consider for your own situation not just what is needed to govern “the now” but what will be needed going forward; that's critical. Keep in mind that there are other frameworks that could be included to enhance or replace these, to better apply to your business and family life stages. Be cognizant, moreover, that I constructed this example by cross-referencing the four entities with the dimensions that make up the frameworks. Where there is not an obvious match-up, I generally list the framework.

The intent here is twofold. First, to add breadth and depth to the discourse and nurture understanding. Second, it provides an opportunity to become even more acquainted with the frameworks and to appreciate how they can be maneuvered to facilitate different aspects of the continuity model and Continuity Canvas development processes. I intentionally repeat this to stress that this is the process required to build your own canvas.

Illustrated Table 4 POPULATING THE FOUR GOVERNANCE CATEGORIES USING THE FRAMEWORKS

Business Governance

Keystone Meta-Framework: Four Foundational Theories

Theorists and other scholars have spent lifetimes trying to figure out governance. The nomenclature has evolved over time, but “corporate governance” seems to be the current agreed-upon positioning. In simple terms, corporate governance describes how best to direct and control an organization. An expanded description would be the systems and frameworks outlining the rules, relationships, and processes within and by which authority is exercised and controlled in corporations.

A central component of governance is the assembling of directors in boards to act as agents on behalf of owners. To minimize potential for agency costs, agents are expected to act in the best interest of the organization, avoid conflicts of interest, and not misuse their position or the information to which they have privileged access. More specifically, they are to prevent insolvent trading and expected to disclose related party transactions and their interests.

Agents, moreover, are bound by behavioral expectations associated with the business judgment rule. This effectively stipulates that the law does not intend to inhibit proper entrepreneurial activity, but directors must meet set judgment requirements for care and diligence:

- Make the judgment in good faith, for a proper purpose.

- Do not have material personal interest in the subject matter of the judgment.

- Inform themselves about the subject matter to the reasonable extent they believe appropriate.

- Rationally believe that the judgment is in the best interests of the corporation.

The resource-based view, covered in Part I, relies on family input to properly establish “familiness” resources. Similarly, governors and directors, whether family or external, need a working understanding of the resources available that are idiosyncratic, to enable them to guide the bundling that builds unique capability, which drives strategic planning and sustained differentiation and performance. Family owners, therefore, have a responsibility to:

- Clearly define values,

- Clarify stakeholder priorities,

- Provide shared vision,

- Set shareholder goals, and

- Assure unity and commitment.

Familial Meta-Framework: Business Governor – Family Governor

Business governors are expected to oversee business performance and ensure conformance with legal frameworks. Their decisions are bound by a set of rules and objectives contained in a document known as a constitution, previously a “memorandum and articles of association.” However, how this is termed may depend on the jurisdiction. The company's constitution is a contract between the shareholders and the company, and each person who applies to be a shareholder or member of the company agrees to abide by the documented rules.

Business governors (i.e. directors), moreover, understand that their duty is to the company, not to the constituency they represent. This sentence and notion is important; read it again. This also relates to the family governors, though it is not legally binding in the family context.

Directing the business or the family requires mastering independent thinking and judgment. Go ahead and read that again as well. Then, consider asking yourself and others this question: “to whom are you accountable?”

When making decisions, governors abide by a set of parameters, which were captured eloquently by the King Commission (King 2002):

- Is there any conflict?

- Do I have all the facts to enable me to make a decision?

- Is this a rational decision based on all the facts?

- Is the decision in the best interests of the company?

- Is the communication to stakeholders transparent?

- Is the organization acting in a socially responsible way?

- Am I a good steward of the organization's assets?

- Would the board be embarrassed if its decision and the process employed in arriving at its decision appeared on the front page of a national newspaper?

Considering that there is more than one type of board is important. They range from passive to active. Passive boards meet minimal requirements and can be often described as cosmetic. Active boards at a minimum provide oversight (i.e. overseeing those who do), and, ideally, are full blown decision-making forums. Related to strategy, they need to establish (i) arenas: where will we be active? (ii) vehicles: how we are going to do it? (iii) differentiation: how we will be seen to be different? (iv) staging: what will be the speed and the sequence of moves? and (v) economic logic: how does what we do translate into financial terms?

In addition to strategy, the board has a role in crafting the mission. This involves (i) establishing a focused conceptual approach (i.e. the what), (ii) the meaning of what it is we do (i.e. the why; the noble purpose), and (iii) the plausible chances of success (i.e. the aspirational goals).

Some insightful boards steer their constituents away from mission statements to rather concentrate on “commitment statements.” Such commitment statements can vary for different stakeholders, e.g. employees, customers, family, and owners. The additional granularity of this contextual approach is obvious and meaningful.

Individual Meta-Framework: Four Tests Framework

Any individual strategizing their career—or involvement—in the family or the business needs to be comfortable with that which distinguishes family businesses from others. When (not if) asked by an independent, objective evaluator how they see the differences, rather than shoot from the hip they should be prepared with an evidence-based answer. More specifically, a strong response could sound like this: “The competitive advantages that family enterprises have over others, according to research, include their speed to market, which stems from their concentrated ownership that leads to efficient decision-making and response time. They are also more likely to have an intentional strategic focus on niches. Their characteristic long-term perspective ensures a commitment to quality. They invest patient capital and are renowned for their agility and flexibility and typically enjoy lower overall cost structures.”

A response like that is the tool of the trade for anyone serious about contributing to this domain. It is also something that an external director should understand, particularly those with a publicly traded company pedigree.

If you are a candidate seeking a governance role, consider responding with what the research says about best-practice governed family businesses. A version of this should do it: “In award-winning family business, that is, those who are considered best-practice in governance terms, shareholders act as long-term proprietors. The board is deeply invested, which means they are motivated to undertake disciplined monitoring of financial and non-financial results. The CEO is typically compensated mostly via long-term incentives. That person is usually an insider who has considerable experience and a list of substantive accomplishments. The CEO is values- and mission-driven and typically stays in the job for decades. That executive is supported by a top management team with a strong voice and diverse functional backgrounds, with members who are multigenerational and enjoy long tenures. The leadership's philosophy is centered on careful stewardship over the mission as well as assets and resources. They have a reputation for being willing to listen and invest in capabilities to enhance prospects of long-term success.”

Enough said!

Generational Meta-Framework: Learn Our Family Business

Many of the current popular corporate governance practices may be detrimental to family businesses in that they may harm family unity, might be too complex for private firms, and/or are applicable only to very large, public companies with dispersed ownership. This reinforces the need to spend time in L2 of the Four Ls: learn our family business. It is here that the next generation can understand their family business governance needs and design the appropriate governance architecture, in consultation with incumbents and advisors. It is during this time that they will appreciate that which is different not only with regard to their family business, but for family business writ large. Specifically, they will come to know the importance of being accountable, or the need to justify decisions made and accept responsibility for their implementation. This accountability will entail avoiding conflicts between family members' roles in the family and business, while preserving an atmosphere of trust and unity.

In L2, there is a need to understand risk, as that will be fundamental to individuals' ability to lead (as expected in L3). They will need to review the business's risk appetite, consider structures for risk management, establish measures to supervise risk, introduce ways to implant risk into governance, and design crisis management protocols. Remember the board is responsible for supervising risk while management is responsible for managing risk.

One recommendation is that these family leaders will need to champion, if not already in place, the introduction of external directors to the board. This will have many benefits and contribute significantly to continuity. Call them “externals” rather than independents, because anyone sitting on the board should be an independent thinker. These externals bring value through their unbiased, objective views. Not being mired in historical influences on the company or family, they bring fresh broad perspectives. As well, they bring a network of contacts and, because of their non-operational role, they are more likely to hold management accountable for their actions.

When asked if there is one thing that a family can do to increase their chances of continuity, pioneer family enterprise scholar Professor Emeritus John Ward will reply, “Appoint externals to the board.” When asked “How many?” he will answer, “Minimum of three.” When further probed regarding “How many family?” he'll say, “It doesn't matter as long as there are three externals.” Admittedly, it is a bit more complicated than that, but I include this idea to add gravitas to the importance of getting this done while in L2.

A good way to frame what value an external brings to the discourse is to consider that they don't tell, they ask. Their role, often times, is to “cause you to pause,” and be more deliberate in making decisions. Jim Ethier, the Emeritus Chairman at A.H. Bush and Co., explained it well when he shared that “a board is like the group of consulting physicians grouped around a hospital bed considering prognosis and best procedures for a patient. They arrive to consensus when all relevant information and perspectives are shared. They also do this in a timely fashion, acting with a sense of urgency not a sense of panic.” He also stresses that gender mix is important in order to capture the gamut of perspectives.

Tactical Meta-Framework: Governance – The Governor

The board needs to understand, test, and endorse the business strategy. While some boards adopt a traditional approach whereby management develops the strategy for board approval, a contemporary approach sees the board shape the direction and drive performance in collaboration with management.

Regardless, a governor (director) has legal duties, which will be a version of five things:

- A duty to act with due care and diligence.

- A duty to act in good faith.

- A duty not to gain advantage by improper use of the position.

- A duty not to misuse information.

- A duty not to trade while insolvent.

The governor contributes to the board, which is responsible as a group for ensuring the creation of long-term sustainable value. As part of this responsibility, directors appoint and oversee the CEO, who recruits management to carry out day-to-day activities within the framework of policies and strategic guidelines established by the board. The top executive is also responsible for making resources available to management to achieve the strategic plan.

The chairperson's governor role is more important than many realize. To some, the chairperson's role is as a figurehead, but in reality, it is to ensure the board functions optimally. The chairperson does this by assuming responsibility for six things:

- The board's general performance,

- The flow of financial information to the board,

- The establishment and maintenance of systems to facilitate the flow of information to the board,

- Public announcement of information,

- Maintenance of cash reserves and group solvency, and

- Making recommendations to the board as to prudent management.

In the corporate governance world, the board is the ultimate decision-maker. Each member of the board is held individually accountable for the outcome. The chairperson manages the process but is not alone in being responsible for the quality of debate. Leaving footprints in the sand is recommended. That means establishing a pathway for how decisions are made, which could include (i) collecting and assessing relevant data, (ii) identifying and framing the primary issue(s), and (iii) bringing others along.

Being a governor requires a heightened tolerance of ambiguity. Decisions are made with imperfect information. That is just the way it is. But it is the director's responsibility to structure their questioning. A template could include five items:

- Have we been presented with adequate information?

- Will the key assumptions hold up?

- What will the competitors' response be?

- What is the risk involved and the penalty in case of error?

- Are the more common points of project failure covered?

Fundamental Meta-Framework: Renewal – Business-Driven Capabilities

Governing for continuity may involve a different approach to that pursued to date. Governors in a continuity paradigm may need to address ingrained habits related to several areas:

- Secretive traits that can affect compensation systems, incentives, information systems.

- Organizational habits developed during the entrepreneurial stage that inhibit strategic renewal and change.

- An ingrained tendency for quick decision-making.

- Culture that may be more oriented to the personality of the leaders than to the requirements of strategy.

- A next generation that struggles to gain organizational power and respect necessary to successfully implement strategies.

Any review of governance effectiveness could include four areas and related questions:

- Board composition: Does the Board have the right people and structures in place?

- Governance relations: Are the members of the governance system (board, CEO, company secretary) interacting constructively?

- Internal processes: How efficiently does the board manage governance processes such as meetings, information flows, and others?

- Stakeholder communications: How effectively does the board communicate with its key stakeholders?

Family Governance

Keystone Meta-Framework: Family Steward

Recall the four ways that costs can be incurred when agents are not stewards: entrenchment, altruism, adverse selection, and information asymmetry. This applies equally to family and non-family. So, it's critical to understand these four potential costs and that good governance is what reduces their potential impact. Revisit this to strategically and comprehensively craft your family's governance philosophy.

Familial Meta-Framework: Sense of Purpose

The real purpose of committing to governance in the family, the ownership, or the business systems is to demonstrate a commitment to family unity that motivates the collective to be effective owners and to support their businesses for the long term.

Individual Meta-Framework: Political

Governing an increasingly diverse family of families is likely to be politically charged. Knowing that there are differences should drive the development of role clarity and transparency through governance initiatives. As Ward maintains, “you govern a family like you cook a small fish…gently.”

Generational Meta-Framework: Learn to Lead

The Four Ls applies to both governance roles and operational roles. So, follow the Ls. L1: learning business is a prerequisite for any governing role in business or family. L2: learning our family business is non-negotiable for governors. L3: learning to lead will help to govern our family business. L4: learning to let go any governance role (not just operational role) is important.

The message that one family took away from interpreting the Four Ls is that “each generation needs to conquer the business…and a lot of what is required to do that happens in the second L.”

Tactical Meta-Framework: Four Rs

One of the Four Rs relates to Remuneration. This is important to address for any governance role. Note that there are two cells of the Four R matrix that must be completed: remuneration for a role as a director and remuneration for a family governance role. The suggestion for the former is to set compensation to market. This is not a universal solution and should be established depending on circumstances. Some families maintain that family directors are already adequately compensated through their dividend and, for those who work in the business, through their salary. So, they don't consider additional compensation for governance roles appropriate. Fair enough. Others take the opposite perspective and set compensation for any director role and related committee activity at market rate. Again, fair enough. Both can work. But there is a need to be transparent. Some opt for taking compensation for governance roles but direct it to philanthropic initiatives, for example. A win-win solution. Regardless, there is a need to understand the other two Rs (requirements and responsibility) for the role as governor.

The second role as a family member, again, does not come with a universal remuneration solution. A common approach is to compensate for special project work or leadership roles, but not for other roles. Other incentives such as being able to attend education programs and conferences can be attractive. Whatever the approach, it should be clearly articulated in the family protocol or some such document. One thing that can be expected is that voluntary family governance roles are fatiguing and keeping levels of motivation high becomes problematic. This is normal. Creating meaningful roles with appropriately meaningful compensation is an ongoing challenge.

Fundamental Meta-Framework: Trust

Recall, the aim of the game is to build trust within, between, and among a team of decision-making teams. Within the different boards (business, family, ownership, foundation), between each of these in dyads (business–family, business–ownership, business–foundation, family–ownership, family–foundation, ownership–foundation), and among the business, family, ownership and foundation boards. Revisit the trust dimensions i.e. Integrity, Ability, Benevolence and Consistency.

Ownership Governance

Keystone Meta-Framework: Owner–Stewards

As in all governance roles, owners–stewards are expected to fulfill compliance and performance roles. To external stakeholders, they provide accountability and oversee the formation of strategy. For internal stakeholders they are required to monitor and provide oversight and make policy.

Governing for continuity requires developing a hybrid approach, which mixes some aspects of the market model of governance with some from the control approach. Consider that the market model prescribes high levels of disclosure, independent board members, shareholders who view their holding as one of many assets they hold, and that ownership and management are separate. These are blended with control-model components including a focus on long-term strategy, shareholders who have connections other than financial (i.e. as executives and board members), where ownership and management can overlap significantly.

Familial Meta-Framework: Four Ps — Protocols Before Needed

While not relevant only for ownership governance, this is as good a place as any to consider how board processes can be established and improved. One thing that may be apparent is that no matter whether we are governing the business, family, ownership, or foundation, for continuity there are some practices to which we should consistently adhere. So, in the spirit of putting in the protocols (practices) in places before they are needed, what are those practices? Here are key items of consideration as you craft your family's governance philosophy.

As far as meetings, a good rule of thumb is that “more is more,” at least initially: err on the side of scheduling more frequent meetings until there is a level of comfort with the discipline of formal meetings. Eventually, the recommendation for business meetings is four to six per year. The reasoning is that management will have time between meetings to have acted on any directive from the board. In other words, leave time between meetings to avoid having to discuss the same topics at each.

For meeting duration and timing, half-day meetings are preferred, and many prefer holding them on Mondays: or at least early in the week. The idea is to allocate time on the preceding weekend to preparation. That means distributing minutes and agendas with ample time to facilitate preparation. One board retreat per year, if possible, is also recommended.

It's ideal to have the business board, family board, ownership board, and foundation board meet in the same week four times a year. This will of course mean multiple meetings for those who occupy multiple roles. But the efficiency of setting a calendar like this outweighs any inconvenience or perception of workload. The work still must be done. This also means that informal gatherings can be scheduled at the same time, so that family members can connect with each other, along with externals, management, and advisors.

As noted above, agendas must be designed carefully and distributed in advance. Put more bluntly, a meeting without a thoughtfully constructed agenda is a waste of time. I'll say it again: a meeting without a thoughtfully constructed agenda is a waste of time. A well-designed agenda aids the flow of information and shapes subsequent discussion for any board. It directs attention to what is important. Before the meeting, it guides preparation. During the meeting, it acts as an objective control of progress, given how quickly things can get off-track. Afterward, the agenda serves as a measure of meeting success. Indeed, you know when the meeting has been effective and efficient; it's typically because the agenda was well thought through and the chairperson aligned discussion with the agenda's roadmap.

Similarly, board papers are art. These critical documents should include the agenda; minutes from previous meetings; major correspondence; CEO's (or equivalent's) report including a report on risk/compliance; financial reports; and documentation supporting submissions that require decisions. An easier way to say that is that board papers need to include matters for decision, matters for discussion, and matters for noting, in that order. For fiduciary boards (legal boards) there is a greater expectation of ensuring compliance with governance protocols and following stricter parameters, but the intent should be the same regardless of the type of board. A trap that some boards fall into is spending so much time complying with legislated protocols that no substantive discussion takes place. Beware this trap. Or the inverse of that, where there is a lack of adherence to protocols, and it becomes a “talk fest” dominated by those with the loudest voices. Either will be a deterrent and a motivator for family members and externals to avoid meaningful participation.

Similarly, the construction of board minutes is an art form. The minutes serve several important functions, such as tracking what happened in the meeting, providing a record for those unable to attend, housing special instructions for committees and others, and representing a permanent record for outside parties that may need to evaluate past decisions. I suggest this is an art form because it is not easy to capture, in detail but parsimoniously, boardroom conversations. Navigating the fine line between including too much and too little information requires skill and practice.

Related to the recommendation to bundle board meetings is the need to design the board calendar, including all aspects of board responsibilities. The calendar will include appropriate interaction with management other than the CEO and ensure that more mundane topics such as insurances review are not overlooked. It will also promote the scheduling of activities in logical order. For example, compensation and remuneration reviews must occur before budget meetings. On the logistical end, attending to this enables synchronization of directors' calendars well in advance and, where possible, scheduling of business-site visits.

At some point, you will need to establish board committees. These save time and increase the efficiency of the board process, while providing a training ground for those moving toward the position of chairperson and enabling faster socialization of new directors. The idea of committees also helps address the question of optimal board size. That is, having a board with seven to ten members facilitates the effective formation of committees that perform meaningful work. Any fewer members than that will make committee work more onerous and, ultimately, less effective.

Another board-related question relates to tenure. There is no definitive answer, but it's ideal to establish a formal tenure policy. Externals I respect, who have been brought on to provide independent, objective direction, share with me that there is a time after which they feel they are no longer truly independent. One in particular sticks to a five-year rule. After that he is voluntarily out! Broadly, complacency on the board is the enemy, and the frequent cause of discontent and suboptimal performance. Increasingly, the performance of the individual directors and the board as a group are monitored closely and evaluated after each meeting by the directors themselves and annually by an independent auditor. This type of oversight solves many potential problems (those related to agency and principal cost, for example) and can lead to thoughtful replacement of directors. But again, there is no one right way.

Though a renewable appointment is de rigueur, in the first year the new director is still finding their way. Fit is paramount, so it's best to build into the recruitment process a clear way of exiting someone who has been wrongfully appointed. While plenty of consultancies provide board-recruitment services now, it's important not to outsource these conversations fully.

A final observation. Governing requires serious commitment, and good directors are like hen's teeth. Take care to identify, recruit, and retain them.

Individual Meta-Framework: Persuasiveness

The role of a governor, as noted earlier in the book, is “to persuade and be persuadable.” Simple. It is worthwhile to include the definition of persuasiveness as it was introduced in the servant leadership framework, but with changing the word “leaders” to governors, as below.

Persuasive mapping (persuasiveness) describes the extent to which governors use sound reasoning and mental frameworks. Governors high in persuasive mapping are skilled at mapping issues and conceptualizing greater possibilities as well as being compelling when articulating these opportunities. They encourage others to visualize the organization's future and commit to bringing the vision to life; they are never coercive or manipulative.

Generational Meta-Framework: Sibling Partnership

The four ownership stages framework provided a way to understand the ownership trajectory. Extending that, it is important to acknowledge that there are different types of owners (recall the ownership circle of the three circles framework). These include operating owners, governing owners, active owners, investing owners, and passive owners. The emphasis and mix of types are typically a function of the generation in question. Regardless, owners have four broad responsibilities (with actions in the bullet points):

- To define the values that shape the company's culture.

- Regular meetings and sessions between owners and managers.

- To set the vision.

- Establish parameters and boundaries for management strategies.

- Integrate business strategic planning with family values.

- To specify financial targets.

- Owners propose goals for growth, risk, liquidity, and profitability; the board evaluates feasibility and consistency.

- To elect the directors and design the board.

- Appoint active and independent directors.

Tactical Meta-Framework: Responsibility

The best way, arguably, to start the family governance journey is to populate the four Rs matrix. This will evolve into the family constitution (also known as the family protocol or family charter).

Family constitutions provide the parameters that govern the relationships among owners, family members, and managers. These documents make explicit some of the principles and guidelines that owners will follow in their relations with each other, other family members, and managers. It is an important contributor to family unity.

There are plenty of resources to guide the drafting of a family constitution, and literally thousands of “experts” occupy this space. It is recommended that the experts are engaged to keep the process on track, but not to write the document. This one belongs to the family. Keep in mind, also, that the process is important. Do not rush the process just to produce a document, to tick a box. What's created if you don’t commit seriously will more than likely be meaningless and end up gathering dust on a shelf somewhere. Make it a living document. Understand that no amount of legal expertise can match the goodwill and personal responsibility of family members. The document usually has no legal bearing but can refer to documents that do (e.g. the company constitution, buy-sell agreements, others). Moreover, the development process for a family constitution is a compelling rationale for family meetings and councils in multigenerational family firms.

Anyone who has been through this will reinforce that the process is more important than the document. As part of that process, address the previously “no go” topic areas. You can make up your own list but, on that list, it is advisable to discuss the inclusion of a redemption policy.

Fundamental Meta-Framework: Church

The church represents the family in the church and state framework. Included in the family forums found above the line, in the church, are the family council and family assembly. The family council is the governance body focused on family affairs; it serves the family in a similar way that the board of directors serves the business. It functions to promote communication, provide a forum for resolution of family conflicts, and support the education of next-generation family members and affines.

The family assembly operates in conjunction with the family council, and typically is commissioned when the family becomes too large for everyone to participate on the family council. It is another vehicle for education, communication, and the renewal of family bonds. Assemblies are scheduled annually or biannually and provide a way for family members to engage meaningfully, either in the planning and implementation or through active participation.

The Foundation

Keystone Meta-Framework: Social

The family's foundation is the vehicle through which to deliver on the social-logic-driven initiatives in the two logics framework. It emerges, typically, in multigenerational families as wealth accumulates or as a consequence of a liquidity event such as the sale of a legacy asset. The foundation's role is significant in ensuring long-lasting, impactful societal contributions. While likely bound by legal and structures, there is an expectation that the organization will be governed with the same formality of the business, with a clear strategy, requisite accountability, and transparency, along with the inclusion of external directors.

Familial Meta-Framework: Big Tent—Philanthropy

The foundation is a way to engage family members, both lineal and affines, in the family-owning business ecosystem. The proviso is that there be a clear pathway to make people ready, willing, and capable to contribute in a meaningful way. As such, allocating someone a role in the foundation to park them somewhere with an inflated salary and dubious key performance indicators is counter to what the Continuity Model Generation supports. Don't be tempted. Don't.

Individual Meta-Framework: Empathy and Altruism

While having a business understanding is required, this will likely be complemented by the servant leadership dimensions of altruism and empathy. It is worth listing all five again with a shift in emphasis, as below.

Wisdom can be understood as a combination of awareness of surroundings and anticipation of consequences. The combination of these two characteristics makes governors adept at picking up cues from the environment and understanding their implications. Governors high in wisdom are characteristically observant and anticipatory across most functions and settings.

Emotional healing (empathy) describes a governor's commitment to and skill in fostering spiritual recovery from hardship or trauma. Governors using emotional healing are highly empathetic and great listeners, making them adept at facilitating the healing process. Governors create environments that are safe for employees to voice personal and professional issues. Moreover, followers who experience personal traumas will turn to governors high in emotional healing.

Altruistic calling (altruism) describes a governor's deep-rooted desire to make a positive difference in others' lives. It is a generosity of the spirit consistent with a philanthropic purpose in life. Because the ultimate goal is to serve, leaders high in altruistic calling will put others' interests ahead of their own and will work diligently to meet followers' needs.

Persuasive mapping (persuasiveness) describes the extent to which governors use sound reasoning and mental frameworks. Governors high in persuasive mapping are skilled at mapping issues, conceptualizing greater possibilities, and are compelling when articulating these opportunities. They encourage others to visualize the organization's future and commit to bringing the vision to life; they are never coercive or manipulative.

Organizational stewardship describes the extent to which governors prepare an organization to make a positive contribution to society through community development, programs, and outreach. Organizational stewardship involves an ethic or value for taking responsibility for the well-being of the community and ensuring that the strategies and decisions undertaken reflect the commitment to give back and leave things better than found. They also work to develop a community spirit in the workplace, one that facilitates leaving a positive legacy.

Generational Meta-Framework: Crazy Quilt

The crazy quilt applies to the family foundation. Pivoting from a purely business focus to a more socially focused agenda will likely mean that those “quilters” have a broader, more diverse worldview. Their passion will be about driving positive societal change. Harnessing this passion and complementing and balancing it with commercial nous is not as challenging as it once was. This is a result of the legitimization of social entrepreneurship and impact investing.

The other three principles of effectuation can similarly be applied to the socially anchored agendas of the family foundation. They still need to understand the resources they have at their disposal (bird-in-the-hand), be risk-savvy (affordable loss), and be able to pivot appropriately (lemonade principle).

Tactical Meta-Framework: Customer

The BSC reminds us of the importance of customers. Those charged with governing the foundation need to understand their customers and how demographics influence change. A recent example is the current, fast-moving trend away from previously established norms related to social issues. Current generations, moreover, tend to focus philanthropically more on the sciences and less on the arts than in the past. Also, a clear understanding of partnership arrangements is paramount.

Increasingly, foundations understand the need for sound metrics. Causes that provide little in the way of auditable reporting and accountability are likely not the customer preferred by professionally governed foundations. Several key questions go a long way to remove charlatans and opportunists from the foundation's preferred partner/customer list: Who is the customer? What is their track record? How are they governed? Are there recent testimonials and evidence of performance metrics?

Fundamental Meta-Framework: Business-Driven Capabilities

The understanding that the foundation is a business should drive all discussion. ENOUGH SAID.