CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Threat Hunting

The Rise of Cybercrime

This quote was first mentioned decades ago in the context of the cold war. However, it still resonates today, especially with the rise of cybercrime we are currently experiencing. Modern cybercrime is a sophisticated business with complex supply-chain activities and multiple threat actors working together in synergy. The threat actors are practicing division of labor, where one team is deployed to penetrate defenses and another team is subsequently employed to exploit the data breach. This level of sophistication is possible due to the staggering rewards cybercriminals and organized crime syndicates are achieving.

In 2009, the cost of cybercrime to the global economy was USD 1 trillion according to McAfee, the Silicon Valley based cybersecurity vendor, in a presentation to the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland. McAfee has since announced that cybercrime is estimated to top USD 6 trillion by 2021, according to Cybersecurity Ventures. This has been a significant increase in the last few years. The Cybersecurity Ventures report continues to elaborate that “if cybercrime is a country, it will be the third largest economy after the U.S. and China in the context of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) comparisons.”

Cybercriminals can be found globally and have different skillsets and motivations. Some types of cybercrime persist independent of economic, political, or social changes, while certain types are fueled by ideology and monetary gain. The cyber defenders and the industry face an extremely diverse set of criminal actors and their ever-evolving tactics and techniques. These threat actors are opportunistic in nature. These cybercriminals capitalize on disruptive events such as the COVID-19 pandemic. As COVID-19 spread globally, cybercriminals pivoted their lures to imitate trusted sources like the World Health Organization (WHO) and other national health organizations, in an effort to get users to click on malicious links and attachments.

The recent Solorigate nation state attack is another example of multi-layer sophisticated attacks. These attacks were driven by ideology, not pure monetary gain. We discuss this nation state attack in detail later in the chapter. These examples illustrate that cybersecurity is a key focus area for any organization in our modern cloud-centric world. The proliferation of private cloud, hybrid cloud, and public cloud has introduced another layer of sophistication/increased attack vectors for cyberattacks. Therefore, more focus should be on preventative methods to ensure “modern IT diamonds are secured” in relation to Dean Rusk's comments many decades earlier.

Email phishing in the enterprise context continues to grow and has become a dominant vector. Given the increase in available information regarding these schemes and technical advancements in detection, the criminals behind these attacks are now spending significant time, money, and effort to develop scams that are sufficiently sophisticated to victimize even savvy professionals. Attack techniques in phishing and business email compromises are evolving. Previously, cybercriminals focused their efforts on malware attacks, but they have shifted their focus to ransomware, as well as phishing attacks with the goal of harvesting user credentials. Human-operated ransomware gangs are performing massive, wide-ranging sweeps of the Internet, searching for vulnerable entry points. These vulnerable entry points will be controlled by sophisticated “command and control” systems to disrupt organizations via distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks at the attacker's discretion. Defending against cybercriminals is a complex, ever-evolving, and never-ending challenge.

It is estimated that 50% of the world's data will be stored in the cloud infrastructure by 2025. This equates to approximately 100 zettabytes of data across public clouds, government-owned clouds, private clouds, and cloud storage providers. This exponential data growth provides incalculable opportunities for cybercriminals because data is the fundamental building block of the digitized economy. Chief Information Security Officers (CISOs) and security teams are burdened by conventional solutions that can't adapt to the cloud to effectively prevent cyberattacks. And pressures continue to mount as employees produce, access, and share more data remotely through cloud apps during disruptive events such as COVID-19.

It's staggering to comprehend that an adversary could be “lurking” inside your enterprise for 280 days/9+ months before being discovered and contained. Organizations are required to combat these growing threats and increase their security posture. They have to be proactive in their defense strategies. They also have to react very quickly when the enterprise is under attack. Threat hunting is a key tool available for defenders to protect their digital assets against their adversaries.

What Is Threat Hunting?

There are many different approaches to increasing an organization's cybersecurity defenses against adversaries. One fundamental solution is known as threat hunting. Threat hunting provides a proactive opportunity for an organization to uncover attacker presence in an environment. While no formal academic definition exists for threat hunting, leading global cybersecurity authority SANS defines threat hunting as the “proactive, analyst-driven process to search for attacker tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTP) within an environment.” Attacker TTP must be researched and understood to know what to search for in collected data. Information about attacker TTP most often derives from signatures, indicators, and behaviors observed from threat intelligence sources. This added context should include targeted facilities, what systems were affected, protocols manipulated, and any other information pertinent to better understanding an attacker's TTP.

The threat hunt requires accurate threat intelligence to achieve success. The formal model for threat hunting ensures the focus of the hunt remains on the attacker's outlined purpose of the hunt. This also maximizes the usage of threat intelligence. The presented formal threat hunt model is also agnostic of the analytic techniques employed throughout the hunt, allowing the model flexibility to work with any hunting tools or techniques (i.e., artificial intelligence and machine learning tools, etc.). Threat hunting requires a formal process to protect the integrity and rigor of the analysis; it's similar to incident response in that it requires a formal process to handle an investigation rigorously.

The methodology employed by the adversaries is similar despite the sophistication and diversity of the attacks. It is irrelevant whether attackers use large-scale attacks for financial gain or targeted attacks to support geopolitical interests. A phishing email can be a generic campaign targeting millions of users or a targeted single user (i.e., referred to spear phishing, which we will discuss later in the next section) that represents a socially engineered campaign over many months.

Spoofed domains, referred to as homoglyphs, can be used to trick victims; for example, Microsoft.com and Micr0soft.com, where the first “o” is replaced by a zero digit and can be easily overlooked by human readers. This malicious domain, Micr0soft.com, then can be leveraged to distribute malware, steal credentials, or support a fraudulent website. Subsequently, the same malware can be used to create a botnet (an industry term for a “web robot”) to facilitate a DDoS attack against an organization, distribute ransomware, or steal sensitive information in relation to a nation's critical infrastructure.

The defenders leverage threat hunting to combat adversary behavior to protect against cyberattacks. The defenders use multiple tools and methods to achieve this goal. The defenders investigate commonalities across various environments and ecosystems to understand and disrupt these attack vectors such as phishing, spear phishing, homoglyphs, etc. The defenders dismantle the criminals' infrastructure, sharing information gathered through the course of their investigations. These additional insights are shared globally through defender intelligence networks to increase the security posture of the global software ecosystem. Let's investigate the key cyberthreats and threat actors and explore the key attack vectors the adversaries leverage to penetrate an organization's defenses.

The Key Cyberthreats and Threat Actors

There are numerous threat hunting battlegrounds that cybercriminals utilize to penetrate the organization's defenses. We will discuss in detail a comprehensive set of techniques, tactics, and procedures (TTPs) via the MITRE ATT&CK frameworks in Chapter 3. Following are the most important key battlegrounds. We will discuss them further elaborating with TTPs in Chapter 3.

Phishing

It is estimated that more than 90% of all cyberattacks were initiated via phishing attacks. Phishing is defined by using email as the attack vector to inject malicious code or diverting the user to a “phony site” to harvest user credentials. This is a very popular attack vector leveraged by cybercriminals due to its low barrier to entry and high successful click-through rates by unsuspecting victims. Phishing is usually accredited to mass email campaigns. However, sophisticated cybercriminals target specific individuals and organizations exclusively. This is commonly referred to as spear phishing.

Spear phishing is an increasingly common form of phishing that uses information about a target to make attacks more specific and “personal.” These attacks may, for instance, refer to their targets by their specific name or job position, instead of using generic titles like in broader phishing campaigns do.

According to Trend Micro, the most commonly used file types for spear phishing attacks, accounting for 70% of them, are .RTF (38%), .XLS (15%), and .ZIP (13%). Executable (.EXE) files were not as popular among cybercriminals since emails with .EXE file attachments are usually detected and blocked by firewalls and security intrusion detection systems. Trend Micro also suggests that 75% of email addresses for spear phishing targets are easily found through web searches or using common email address formats.

Figure 1.1 illustrates the credential phishing process. Cybercriminals begin by setting up a criminal infrastructure designed to steal an individual's credentials. Note that there are phishing kits available on the “dark web” to facilitate this process. Cybercriminals send malicious emails to the unsuspecting individual, who then clicks on a link within the email. The individual might then be taken to a fake web form that impersonates a real page (such as a bank login page) to enter their credentials, or the site might contain malware that's automatically downloaded to their device, capturing credentials stored on the device or in the browser memory. The victim's credentials are then collected by the cybercriminals, who use the credentials to gain access to legitimate websites or even to the victim's corporate network. This access can be temporary or turn the victim's machine into a zombie in persistent form, and they can receive commands from the Command and Control (C2) servers for the future gains.

Ransomware

There has been massive growth of ransomware in recent years. The bad actors are notorious for injecting ransomware into phishing emails to infect computers and mobile devices. This results in locking up files, and they often threaten complete destruction of data unless the organization pays the ransom.

Figure 1.1: Phishing lifecycle implemented by cybercriminals

Note the ransomware damages are not limited to ransom payouts. The percentage of businesses and individuals who are paying via digital currencies (i.e., Bitcoin) to reclaim access to their data and systems are not accurately tracked. Therefore, the actual monetary impact of ransomware attacks could be seriously understated. Other ransomware costs include damage and destruction (or loss) of data, downtime, lost productivity, post-attack disruption to the normal course of business, forensic investigation, restoration and deletion of hostage data and systems, reputational harm, and employee training in direct response to the ransomware attacks.

Figure 1.2 illustrates the steady rise of ransomware from 2015 to 2021.

Figure 1.2: Global ransomware damage costs

Ransomware attacks have been increasing in complexity and sophistication over the years. Cybercriminals perform massive wide-ranging sweeps of the Internet to search for vulnerable entry points. Alternatively, they enter networks via “commodity Trojan malware” and leverage command and control mechanisms to attack at their discretion. Recently, commodity platforms are being offered in underground markets and the dark web with customizable ransomware tools (called Ransomware-as-a-Service), where one can build ransomware and target particular victims/organizations by subscribing to the service and customizing the payload based on the target vulnerabilities. As an example, cybercriminals used Dridex (a strain of banking malware that leverages macros in Microsoft Office) to gain initial access to networks, and then ransomed a subset of them with the DoppelPaymer ransomware during the 2019 Christmas holiday season.

WannaCry was one of the more sophisticated ransomware operations; it was targeted at many organizations, including but not limited to government agencies, utilities, and hospitals across the globe. During this incident, 16 hospitals in the UK were impacted and patients' lives were threatened due to the disruption and lack of access to their medical records.

As another example, cybercriminals exploited vulnerabilities in VPN and remote access devices to gain credentials, and then saved their access to use for ransoming hospitals and medical providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Cybercriminals actively employ different tactics and change their tack based on the configurations they encounter in the network. They decide which data to exfiltrate, which persistence mechanisms to use for future access to the network, and ultimately, which ransomware payload to deliver.

Figure 1.3 shows an example of how various ransomware payloads are delivered according to the Microsoft Cybersecurity Intelligence Report. These attack vectors and tactics are explored in detail in Chapter 3.

Nation State

A nation state threat is defined as cyberthreat activity that originates in a particular country with the specific intent of furthering national interests. Nation state actors are well-funded, well-trained, and have more patience to play the “long game.” These factors make the identification of anomalous activity very difficult. Similar to cybercriminals, they watch their targets and change techniques/tactics to increase their effectiveness.

Figure 1.3: Ransomware tactics and lifecycle

The defenders investigate top-level trends in country-of-activity origin, targeted geographic regions, and the top nation state activity groups. According to the latest research, nation state activity is significantly more likely to target organizations outside of the critical infrastructure sectors. The most frequently targeted sector has been non-governmental organizations (NGOs). These are advocacy groups, human rights organizations, non-profit organizations, and think tanks focused on public policy, international affairs, or security. The nation state actors have these common operational aims regardless of the strategic objectives behind the activity:

- Espionage

- Disruption or destruction of data

- Disruption or destruction of physical assets

The most common attack techniques used by nation state actors are reconnaissance, credential harvesting, malware, and virtual private network (VPN) exploits. Advanced nation state adversaries invest heavily in the development of unique malware in addition to using openly available malicious code.

Surprisingly, nation state attackers have targeted “non-government” entities contrary to popular belief of focusing on government critical infrastructure. Figure 1.4 shows a breakdown of key industries that nation state attackers have focused on, according to the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Report.

Figure 1.4: Industry breakdown of nation state attacks

Combating nation state actors is a very complex process that involves both technology challenges and legal jurisdiction challenges. The Microsoft threat intelligence team published the threat actor report in Figure 1.5, which classifies each known threat actor (color-coded by nation state). Note the symbols of the periodic table are used to identify and classify the threat actors.

There are known threat actors (i.e., identified by Advanced Persistent Threat, or APT suffix) and other unique threat actors specifically engineered to bring down the defenses of the target nation.

The report continues to name the most common nation state threat actors, as shown in Figure 1.6.

Nation state attacks are “covert” in nature and are not exposed to public scrutiny. However, there have been some recent high-profile nation state attacks that captured the public's attention. The SolarWinds nation state attack (commonly referred to as Solarigate) was exposed in the late 2020 as one of these high-profile cyberattacks. Solorigate represents a modern cyberattack conducted by highly motivated actors who demonstrated they won't spare resources to reach their goal. The collective intelligence about this attack shows that, while hardening individual security domains is important, defending against today's advanced attacks necessitates a holistic multi-layer defense strategy. A summary of the key attack vectors is as follows:

Figure 1.5: Nation state attack adversaries list

Figure 1.6: Breakdown of major nation state actors

- Compromise a legitimate binary (DLL file) belonging to the SolarWinds Orion Platform through a supply-chain attack.

- Deploy a backdoor malware on devices using the compromised binary to allow attackers to remotely control affected devices.

- Use the backdoor access on compromised devices to steal credentials, escalate privileges, and move laterally across on-premises environments to gain the ability to create Simple Access Mark-up Language (SAML) tokens. An intruder, using administrative permissions, gained access to an organization's trusted SAML token-signing certificate. This enabled them to forge SAML tokens that impersonate any of the organization's existing users and accounts, including highly privileged accounts.

- Initiate anomalous logins using the SAML tokens created by a compromised token-signing certificate, which can be used against any on-premises resources (regardless of identity system or vendor) as well as against any cloud environment (regardless of vendor), because they have been configured to trust the certificate. Because the SAML tokens are signed with their own trusted certificate, the anomalies might be missed by the organization.

- Access cloud resources to search for accounts of interest and exfiltrate data/emails.

The Necessity of Threat Hunting

In a digital climate that is changing at an incredibly rapid pace, it is unrealistic to believe that your organization will never be compromised. It is impossible to eliminate every threat to your organization, so you must be able to perform early detection and remediation. At the same time, think twice if you think your company is too small to be targeted by threat actors. Organizations are now going on the offensive and thinking about proactive ways to hunt for threats.

Three things are required before an adversary can be considered a threat: opportunity, intent, and capability to cause harm. No cybersecurity system is impenetrable or capable of recognizing or stopping every potential threat.

Hackers' tactics, weapons, and technologies are evolving so rapidly that by the time a new threat signature is learned, defenses may have already been compromised. Organizations are adopting the “assume breach” mentality to counter cyberattacks.

An attacker's goal can change dramatically. This could be as simple as stealing valid login credentials to purchase Amazon goods or as sophisticated and dangerous as bringing down nuclear reactors, causing fatalities. Attackers use stolen credentials to carry out search-and-steal or search-and-destroy missions using tools and techniques unknown to end users. This enables them to go undetected and cause tremendous damage to intellectual property.

Threat hunting is necessary to counter the sophisticated techniques that cybercriminals use to evade detection by conventional means. Attackers are innovating at an alarming rate, creating new forms of attack. Organizations can't afford to wait weeks or months to learn about incidents. From the moment of intrusion, the cost, damage, and impact of an attack grows by the hour.

As a result, an increasing number of organizations are becoming proactive about threat hunting. Threat hunting focuses on identifying perpetrators who are already within the organization's systems and networks, and who have the three characteristics of a threat. Threat hunting is a formal process that is not the same as preventing breaches or eliminating vulnerabilities. Instead, it is a dedicated attempt to proactively identify adversaries who have already breached the defenses and found ways to establish a malicious presence in the organization's network.

Threat hunting is human-driven, iterative, and systematic. Hence, it effectively reduces damage and overall risk to an organization. Its proactive nature enables security professionals to respond to incidents more rapidly. It reduces the probability of an attacker being able to cause damage to an organization, its systems, and its data. This is vital to ensure that confidential data isn't misused or accessed by unauthorized individuals.

An organization's executive leadership or management must guide the purpose of a threat hunt to meet larger, long-term business objectives. The three areas of study defined within the purpose stage include:

- Purpose of the hunt: The overall purpose states why the hunt needs to occur.

- Where the hunt will occur: Purpose also includes scoping the environment as well as identifying assumptions and limitations of the hunt.

- Desired outcome of the threat hunt: The desired outcome should align with business objectives and indicate how the threat hunt supports reduction of risk.

Here are some examples of why a hunt takes place:

- Connection of a new network to an existing trusted network following a corporate merger or acquisition

- New threat intelligence suggesting the presence of an attacker in the environment

- Desire to gain higher awareness and confidence of the environment

While purpose does not take over the task of scoping the threat hunt, purpose provides general guidance that might focus a threat hunt on a desired regional or subsystem area of interest to business objectives. Finally, purpose focuses on the end outcome of the hunt. Outcomes may include the discovery of an attacker within the environment or identification of gaps in incident response processes that drive acquisition decisions.

Attacks that have made recent news were able to breach organizations that were not taking a proactive approach to security. WannaCry, as discussed, exploited a Windows vulnerability using EternalBlue exploit tools developed by U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) that had been identified over a decade ago. Because the victim organizations had not performed aggressive threat hunting, an erroneous service served as the perfect vector for the attackers. Meanwhile, the EternalRocks malware took advantage of the exact same vulnerability, meaning that many organizations failed to act even after the WannaCry attack.

Implementing a threat-hunting capability or program, along with standard IT security controls and monitoring systems, can improve an organization's ability to detect and respond to threats. It takes skilled threat-hunting experts to implement an effective program since threat hunting is primarily a human-based activity.

Once you understand and accept that you will be or already have been targeted and possibly compromised, you will be able to address security through a more realistic lens. The next step is outlining what actions you need to take to quickly and proactively defend against malicious activity.

Here is the checklist for any organization where threat hunting comes into play:

- Planning: Identify critical assets.

- Detection: Search for known and unknown threats.

- Responding: Manage and contain attacks.

- Measuring: Gauge the impact of the attack and the success of your security.

- Preventing: Be proactive and stay prepared for the next threat.

Does the Organization's Size Matter?

Organizations of all sizes and industries would prefer to detect every possible threat as soon as they manifest. This is the primary outcome of increased spending on automated cybersecurity solutions.

Threat hunting entails a more mature organization with a defensible network architecture, advanced incident response capabilities, and a security monitoring/security operations team. A relatively mature organization can start a threat-hunting program by planning and allocating time and people, but the undertaking does not call for expensive tools or years of experience. Small and medium-sized organizations could start with simple and progressive steps and gradually extend on the data types and scenarios. Note that even threat hunting does not always find signs of a compromise, but it dramatically increases visibility and understanding of your environment. The automated tools can only do so much, especially since new attacks may not have signatures for what's most important and the fact that not all threats can be found using traditional detection methods.

To keep up with ever-resourceful and persistent attackers, organizations must prioritize threat hunting and view it as a continuous improvement process. These teams would also be well served by investing in technologies that enable hunting and follow-on workflows. For example, if threat-hunting methods are discovered that produce results, make them repeatable and incorporate them into existing, automated detection methods. If the same threat-hunting workflow keeps getting repeated and produces results without a lot of false positives, try automating those workflows.

The effectiveness of threat hunting greatly depends on an organization's level of analyst expertise as well as the breadth and quality of tools available. An organization's acceptable risk level, IT staff makeup, and security stack can also impact the type of threat hunting that's feasible. In doing so, organizations can ensure all analysts are able to hunt and better protect critical business assets, regardless of their skill level.

The recommendation is to hire an outside security firm specialized in threat hunting for small and medium business organizations with no threat-hunting experience or for businesses without an IT department.

If your business lacks the budget to hire an external company, turn to software tools specializing in threat-hunting techniques. Some security software can automate the process to a degree.

Another area of focus is educating staff to prevent and recover from attacks. Cybercriminals leverage phishing emails to trick employees. Therefore, educate the organization's staff about the signs of phishing and other security best practices.

Threat Modeling

Threat modeling is at the heart of threat hunting. There are different methodologies defined for threat modeling. Threat modeling should be improved over time by expanding the coverage and threat actors targeting the organization or same industry, and/or using similar platforms and attack applicability.

There are two prerequisites for threat modeling:

- Asset inventory with criticality levels should be defined.

- For each of those assets, security mitigation and defense controls, including but not limited to Firewall, IDS, Antimalware, Endpoint Detection Response (EDR), Data Leakage Prevention (DLP), Authentication, Authorization, and Encryption Controls should be listed.

Knowing what platforms, assets, and security controls are available helps threat-modeling and hunting teams define the scope and priorities of their planning. Depending on the maturity level, the scope should be started small and grow as the maturity level increases. Using the aforementioned items, threat-hunting finding and investigation should be prioritized based on its impact and likelihood. The threat model should be mapped based on the organization's assets.

Threat modeling is a systematic approach of proactively assessing the weakness of the IT environment and assets and, based on their criticality level and potential vulnerabilities, a remediation plan should be developed. Defining the scope plays a critical role as part of developing a successful threat-hunting program. The components outlined in Figure 1.7 are required before planning threat modeling.

Figure 1.7: Components of threat modeling

There are several threat modeling methodologies available. One of the leading industry models is the Microsoft Security Development Lifecycle (SDL), as shown in Figure 1.8. It defines the threat modeling approach in the following five steps.

Figure 1.8: Microsoft Security Development Lifecycle

- Defining the scope and depth of the analysis. At this stage, the scope and depth of threat hunting should be defined based on threat modeling. Obtaining a list of assets and their criticality assists with the rest of the process in scoping and defense and remediation planning.

- Gaining an understanding of what you are threat modeling. At this stage, based on the collected system, threat hunters should understand the components of each asset. It helps them to profile the standard architecture and flag it in the future if suspicious changes and interconnections take place. Architecture diagrams at this stage should be gathered for further review. Furthermore, the business workflow gives the required insight to threat hunters for future behavioral analysis.

- Modeling the attack possibilities. Defining a list of assets, existing security controls, and identified vulnerabilities and misconfigurations. In the next stage, a system architecture outlines a potential triggering threat agent or failing the control that could lead to an incident.

- Interpreting the threat model. At this stage, threat hunters should wear their “hacker hats” and think similar to a hacker and analyze the possibilities. Having the threat intelligence feeds at this stage helps to extract the required knowledge of threat actors and TTPs. Additionally, threat actors should constantly think of alternatives to bypass certain controls and be proactive.

- Creating a traceability matrix to record missing or weak controls. At this point of threat modeling, based on the findings, mitigation control should be assessed:

- Threat agent

- Asset

- Attack surface

- Attach goal

- Impact

Threat hunters, by knowing these details and the threat landscape and current relevant threat actors and their TTPs, should also advise if any vulnerabilities need to be remediated or existing security controls are not sufficiently strong enough. This “risk rating” will be defined at this stage. If any of the aforementioned issues cannot be addressed at this point in time, the threat hunter should consider those issues as a high priority in their watch list.

Note that during this stage, business objectives and strategy should also be strongly considered. For instance, if it is a military organization, confidentiality and integrity are paramount. Applying this to a financial sector organization, availability should be added as an additional key concern.

The following questions should be answered regardless of what threat modeling techniques are leveraged:

- What is the defined scope? And what should be worked on?

- What are the odds? And what could fail or break?

- What is the action plan for them?

- Is our mitigation control effective enough?

There are various threat modeling tools and frameworks that could be utilized. Since our focus is on threat hunting, MITRE ATT&CK can be a better option to leverage (see Figure 1.9). The MITRE ATT&CK framework can be one of the key frameworks applied during the threat modeling process. However, it is important to take note that the MITRE ATT&CK focuses on potential attack vectors. Hence, during risk assessment, system criticality, threat impact, and the likelihood of modus operandi need to be considered. Therefore, participation of system and business owners are especially important during risk modeling when using the MITRE ATT&CK framework.

We will discuss the MITRE ATT&CK in detail in Chapter 3.

Figure 1.9: MITRE ATT&CK framework

One threat model cannot be applied for all systems since threat landscape and adversaries and TTPs may vary from one industry to another. The output of threat modeling is a list of threat-hunting procedures and processes customized for the organization. These procedures and processes should be automated where applicable.

Threat-Hunting Maturity Model

Many organizations are quickly discovering that threat hunting is the next step in the evolution of the modern Security Operations Center (SOC), but remain unsure of how to start hunting or how far along they are in developing their own hunting capabilities. How can you quantify where your organization stands in relation to effective hunting? With a general model that can map hunting maturity across organizations. Let's consider what constitutes a good hunting program with these questions in mind. There are three factors to consider when judging an organization's threat-hunting effectiveness program:

- The quality and quantity of the data they collect for hunting

- The tools they provide to access and analyze the data

- The skills of the analysts who actually use the data and the tools to find security incidents

Among these factors, the analysts' skills is probably the most important, since that allows them to turn data into “indicators of compromise (IOCs).” The quality and quantity of the data that an organization routinely collects from its IT environment is also a strong factor in determining the Hunting Maturity Model (HMM) level. The more data from around the enterprise (and the more different types of data) provided to an expert hunter, the more anomalies or IOCs they will discover. The toolsets you use will shape the style of your hunts and determine what kinds of hunting techniques you will be able to leverage.

Organization Maturity and Readiness

Threat hunting is one of the defense layers among other existing controls, tools, and processes to mitigate cyberthreats that is necessary for all organizations to have in place. However, CISOs and security strategists should also take note that efficient threat hunting will only be possible in a mature environment where required processes, technology, and people are in place.

An advanced state of the art of threat hunting is where Firewalls, Antivirus, EDR, DLP, and the Security Information and Event Management system (SIEM) are integrated and correlate the rich data. This will assist skillful security analysts leveraging the latest reliable threat intelligence IOC feeds and actionable tactics, techniques, and procedures coming together to find the potentially suspicious activity with minimum false positives. Threat hunting should be considered a “magic wand” that can resolve most of your security loopholes.

When threat intelligence was introduced, there was a misconception that the more threat feeds you had, the more you could protect. Many of those feeds were outdated and unreliable. On the contrary, loading a high volume of IOCs can slow down security appliances. Inspecting every single data packet against millions of IOCs is a very tedious task. Hence, the notion of “actionable and vetted IOCs” was introduced to streamline the threat-hunting process.

Analysts should perform gap assessments and understand the existing enterprise capabilities prior to launching a threat-hunting program. This will define their threat-hunting program, and investment in phases to reach to desired threat-hunting maturity level.

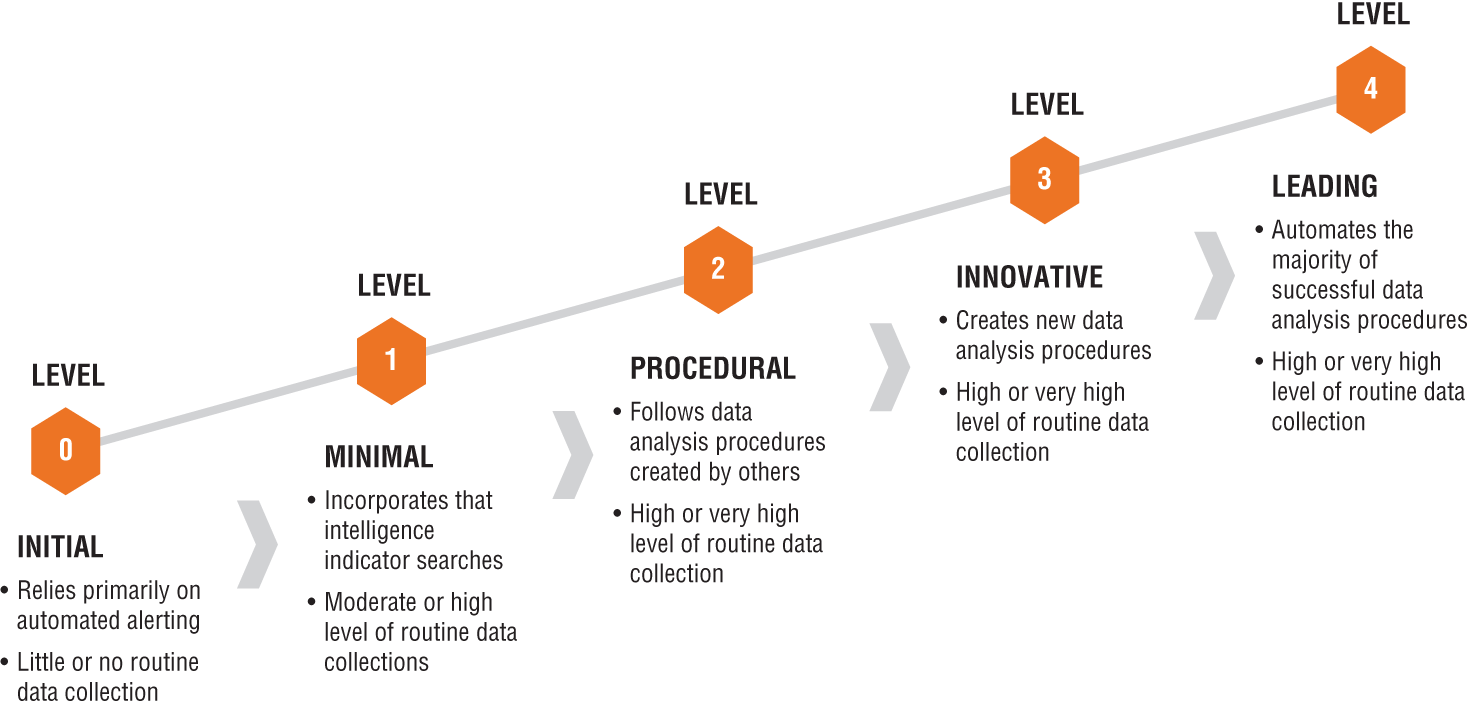

The HMM has five levels, as illustrated in Figure 1.10.

Figure 1.10: Threat Hunting Maturity Model

Level 0: INITIAL

At the foundation level, threat-hunting programs mainly rely on automated alerting tools and correlating tools such as WAF, antivirus, IDS, and SIEM. The collected information is not very comprehensive. Hence, threat hunting at this level is extremely limited and close to 0. No IT data is available at this stage.

Level 1: MINIMAL

Data collection scope is limited to the same automated alerting tools at level 1. However, IT data is included for daily incident response activity by leveraging threat intelligence feeds. Correlated data is usually pumped into the SIEM or into other log management tools. Security analysts at this stage can search based on the IOCs and TTPs for a number of malicious historical activities. However, it is still considered a poor threat-hunting capability.

Level 2: PROCEDURAL

Threat hunting at this level can usually start at the foundation level, where threat analysts and other researchers develop procedures and apply the same method in the organization. At this level, the organization's threat hunting is limited to procedures that are published or shared by other researchers or service providers. However, usually at this point, threat hunters are yet to develop their own customized or innovative procedure.

Level 3: INNOVATIVE

Threat hunters at this stage are more educated and skilled and have more practical knowledge of analysis techniques in order to identify malicious and suspicious activities. Additionally, they manage to obtain more data and use data visualization and machine learning techniques to develop their own procedures. They should be able to develop repeatable procedures. However, they may face challenges when the number of cases increases, and they cannot cope with the number of processes and events and analyze them in a timely manner.

Level 4: LEADING

In the previous section, it was mentioned that threat hunting is not an automated process by definition. At this level-4 stage, hunters should be able to automate the repetitive processes and tune the existing ones, and thanks to automation, they can dedicate more time to building new processes. While automation is increasing, it still requires hunters to frequently review existing cases to improve and build new ones. While there are commercial products that can help you with this automation process, automated services at this point can perform this high-quality human activity. Proper metrics are defined to monitor key performance indicators (KPIs) and Service Level Agreements (SLAs).

Automated risk scoring is leveraged using machine learning, with horizon scanning maintained for future technological developments. Hunts are occurring continuously, with successful analytics and discovered IOCs shared across the community, while the knowledge repository and workflows are integrated with the wider SOC. Data visibility is high across all relevant areas of the estate and is very well understood.

Human Elements of Threat Hunting

For thousands of years, humans have worked to collect intelligence from their enemies. Intelligence gathering is not a new practice; in fact, it is one of the oldest war tactics dating back to biblical times, when warlords and army commanders used it to gain advantages over their rivals.

However, the methods and tactics have changed as new technologies and new forms of “warfare” have been developed. In recent years, cyberattacks have led to an entirely new host of intelligence challenges, especially for corporations, who are not accustomed to the practice of intelligence gathering the way governments are. Yet, CyberThreat Intelligence (CTI) can be critically important to how organizations defend against attacks and uncover their cyber adversaries.

There are many different forms of intelligence gathering, including Open-Source Threat Intelligence (OSINT), Machine Intelligence or Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), and Social Media Intelligence (SOCMINT). However, one source of intelligence that's often overlooked is Human Intelligence (HUMINT). HUMINT can be defined as the process of gathering intelligence through interpersonal contact and engagement, rather than by technical processes, feed ingestion, or automated monitoring. It's a risky practice that requires a very particular set of skills, but it can provide you with the most valuable intel. As threat actors' TTPs and attack strategies change, the one constant behind all attacks is that they are human-driven. Understanding an attacker's motives and tendencies can help organizations make the right strategic cybersecurity decisions.

A cyber intelligence program is all about uncovering who, what, where, when, why, and how behind a cyberattack. Tactical and operational intelligence can help identify the what and how of an attack, and sometimes the where and when. But it's difficult to discover the who and why behind an attack without human involvement and manual intelligence gathering. HUMINT can be used to support longer-term, strategic cybersecurity decisions, and should supplement any other intelligence gathering, feed ingestion, and cyber reconnaissance activities your team is doing. Therefore, manual and automated intelligence gatherings are not mutually exclusive, but rather complementary. Both are necessary for an advanced cybersecurity operation, which is why human-to-human research will always be a critical part of the threat-hunting process.

How Do You Make the Board of Directors Cyber-Smart?

As cyberthreats continue to escalate, boards of directors are becoming increasingly interested in cybersecurity and risk management. This is no surprise, as the board is ultimately held liable and responsible should a breach occur. And it's important because leadership sets the tone for the rest of the organization. They must lead by example when it comes to cybersecurity, and actively participate in, and be supportive of, the mission to be secure. As such, cybersecurity has made its way onto the agenda of many board meetings.

When it comes to threat hunting, the first question that every board of directors may ask is “why should we consider adding cyberthreat hunting to cybersecurity strategy?” This is a strategic question to ask. If your board of directors does not seem to be asking this question, they either are not fully aware of your broader cybersecurity strategy or they underestimate the risk of a potential cyberthreat. It is the responsibility of the CISO to educate the board of directors about the benefits of threat hunting, such as:

- Improve speed and accuracy of response

- Reduce actual breaches based on number of incidents detected thus minimize the reputational and financial damages

- Reduce exposure to external threats

- Reduce resources (i.e., staff hours, expenses) spent on responses

Many surveys conducted in the past show that the majority of organizations using threat-hunting tactics are recognizing measurable improvements in cybersecurity performance indicators.

Ultimately, the board of directors needs a basic education in threat hunting and its relationship to the cybersecurity strategy. It's up to you to provide them with the information that they need to know, so they can understand everything else. They simply can't wrap their minds around things they can't understand. If they don't have a foundation, the rest of the subject matter is going to be very difficult to understand. It's very important that they understand because you want them to approve the resources you need and the budget you want.

Here are a few ways that can help you build that foundation to make your board of directors cyber-smart:

- Build cyber risk awareness: Provide insights about the organization's critical information assets, how they are currently being protected and information about the primary risk that organization is facing.

- Integrate cybersecurity into the enterprise-wide risk management and governance processes: Organizations need to include Cybersecurity risks as part of their overall enterprise-wide risk management instead of looking at it as IT risk. Cybersecurity is a business priority and it impacts across the enterprise—inside and outside. Therefore, the enterprise level governance process can look at Cyber related risk and prioritize for action.

- Educate about the importance of engaging attackers with active defense: Threat hunting is a proactive technique that combines security tools, analytics, and threat intelligence with human analytics and instinct. There is a massive amount of information available about potential attacks—both from external intelligence sources and from an organization's own technology environment. The board of directors needs to know the value of threat-hunting capabilities to aggregate and analyze the most relevant information to proactively engage with attackers and tune defenses accordingly.

- Keep them up-to-date: Let them know what's going on in the threat environment. You can also include information on trends and future analysis. Be sure to touch on what your peers are doing as well.

- Share success stories: Let them know it's not all doom and gloom; that there are some positive things going on as well. It helps to buoy their spirits.

Cyberthreats are daunting. Not only are they complex and constantly evolving, they have the potential to impart significant financial and reputational damage to an organization. Plus, there's no way to be 100% protected. That's why cybersecurity is no longer just the responsibility of IT departments. Boards of directors are ultimately liable and responsible for the survival of their organizations, and in today's interconnected world, cyber resilience is a big part of that responsibility. That means that boards must take an active role in cybersecurity.

The boards of directors can take on the role of cybersecurity leaders within their organizations. The National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD)'s Director's Handbook on Cyber-Risk Oversight outlines five principles that all corporate boards should consider “as they seek to enhance their oversight of cyber risks:”

- Directors need to understand and approach cybersecurity as an enterprise-wide risk management issue, not just an IT issue. As much as we have been saying this, it's surprising how many organizations still associate information security or cybersecurity with IT. Even though most of the reporting structures come up through the IT department, it can't be the central focus because the impacts are organization-wide. The skillsets needed to manage the risks and deal with issues are organization-wide. The board needs to understand that a 1:1 with IT is a mistake, and it's been the underlying cause of many big breach events.

- Directors should understand the legal and regulatory implications of cyber risks as they relate to their company's specific circumstances. With responsibility comes accountability. Executive management and board members are being held accountable for many high-profile breaches, and in many cases losing their positions. Target CEO, President, and Chairman Gregg Steinhafel resigned from all his positions following the massive 2013 data breach. Equifax's CEO Richard Smith resigned following a backlash over the massive hack that compromised the data of an estimated 143 million Americans.

- Boards should have adequate access to cybersecurity expertise and discussions about cyber risk management should be given regular and adequate time on the board's meeting agenda. It's becoming more common to see board members who have a technological or security background. This expertise can really elevate a board's awareness. And more awareness is how we win against cybercriminals.

- Directors should set the expectation that management will establish an enterprise-wide risk management framework with adequate staffing and budget. The NACD handbook specifically mentioned the National Institute of Standards and Technology Cybersecurity Framework (NIST CSF), which was created to enable “organizations—regardless of size, degree of cybersecurity risk, or cybersecurity sophistication—to apply the principles and best practices of risk management to improving the security and resilience of critical infrastructure.” When you're writing your policies or developing your program, having a framework to base it on is very helpful. There's no need to reinvent the wheel!

- Board-management discussion of cyber risk should include identification of which risks to avoid, accept, mitigate, or transfer through insurance, as well as specific plans associated with each approach. Effectively managing cybersecurity risk requires an understanding of the relative significance of organizational assets in order to determine the frequency by which they will be scrutinized for risk exposures. This is no small task. It takes considerable thought and effort, along with a great deal of cybersecurity expertise.

Threat-Hunting Team Structure

There are various structures for threat-hunting teams, and they depend more on an organization's culture and structure than on the size of the security team. The most common team structures are discussed in the following sections.

External Model

This model essentially outsources your threat-hunting activity and can introduce your organization to the concept and benefits of threat hunting. Nonetheless, an external team will never understand your environment like you do, and as a result, this model is less desirable in the long term.

Dedicated Internal Hunting Team Model

Typically, in large organizations and government entities, a small team of skilled, full-time employees are employed as threat hunters. They may have access to alerts from the organization's SOC. However, they are not spending most of their time on alert analysis. The drawback of this structure is creating silos between SOC analysts and hunt team members.

Combined/Hybrid Team Model

A team member might have a combined role of SOC analyst/threat hunter, incident responder/threat hunter, or security team member/threat hunter doing daily hunting in addition to their other duties. SOC analysts already have most of the skills required for threat hunting, so this is an obvious step forward for organizations. This is a typical model for smaller organizations or smaller teams with skilled analysts and strong detection capabilities. The risk in a combined role model is analysts might have other priorities, such as daily SOC operations, leaving no time for threat hunting at the end of the day.

Periodic Hunt Teams Model

In this model, security team members are periodically pulled away from other work to form a threat-hunting team. This might happen weekly, biweekly, or monthly, and it requires a clear plan with a specific task to be effective. This model works for large organizations with a large pool of SOC analysts as well as for smaller ones with a small security team, performing threat hunting just a few hours per week. It is important to rotate team members to give everyone exposure to threat hunting.

Urgent Need for Human-Led Threat Hunting

The most devastating cyberthreats generally involve human-led attacks, often exploiting legitimate tools and processes such as PowerShell. Hands-on live hacking enables attackers to modify their tactics, techniques, and procedures on the fly to bypass security products and protocols. Once inside a victim's network, attackers can move laterally, exfiltrate data, install malware and backdoors for future attacks, and deploy ransomware. While technology, particularly intelligent automated technology, has an important role to play, expert operators are still required. Stopping human-led attacks requires human-led threat hunting.

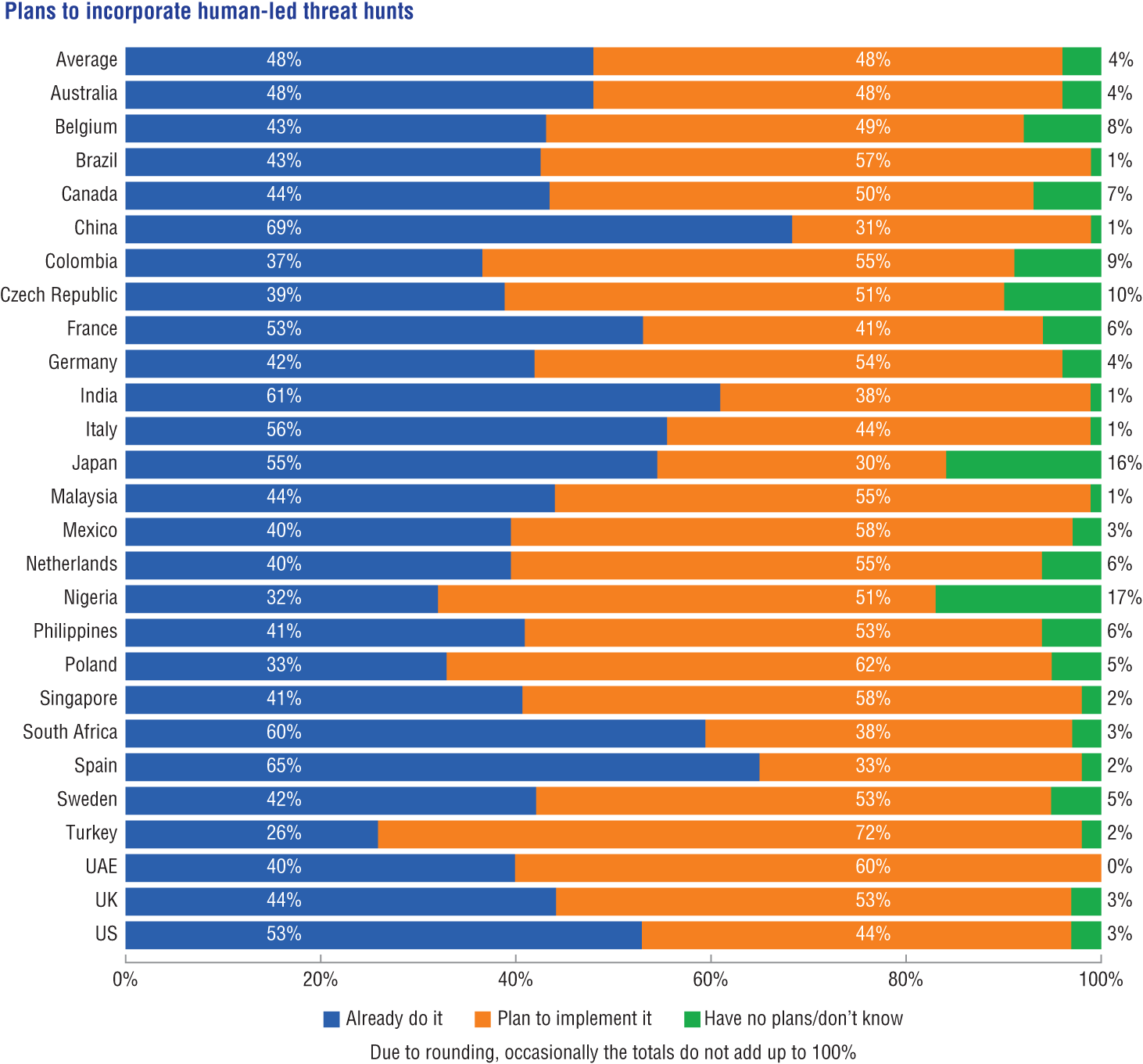

According to a Sophos survey of 5,000 IT managers, 48% already incorporated human-led threat hunts in their security procedures to identify attacker activity that may not be detected by security tools (e.g., SIEM, endpoint protection, firewall, etc.). See Figure 1.11. A further 48% plan to implement it. Respondents are also alert to the urgency of deploying human-led hunting, with virtually all (99.6%) respondents who want to implement it looking to do so within the next year.

The status of human-led threat hunting varies significantly by geography. Sixty-nine percent of respondents from China have already implemented this approach, closely followed by Spain (65%), India (61%), and South Africa (60%). Conversely, Turkey has been slowest to adopt human-led hunting with just 26% of respondents already doing it, with Nigeria (32%) and Poland (33%) only slightly ahead.

The Threat Hunter's Role

The rise of the threat hunter role creates some unique challenges related to the shortage of cybersecurity professionals. As more companies start to adopt security automation, the threat-hunting process steps outside of the box by requiring a highly trained human element.

Figure 1.11: Organizations show their willingness to implement human-led threat hunting

While tier-1 and tier-2 analysts rely on alerts from systems and some combination of manual and automated workflow to escalate and respond to security events, the threat-hunting process hinges on an expert's ability to create hypotheses and to hunt for patterns and indicators of compromise in data-driven networks. Usually, that means tier-3 security analysts with the experience and creativity to proactively discover tactics, techniques, and procedures employed by advanced threats.

Threat analyst activities require awareness of attackers' TTPs, understanding of threat intelligence and data analysis, knowledge of forensics and network security, and plenty of time to carry out these tasks. With tier-3 analysts in short supply, who is going to fill these roles? The skills dilemma may depend on how organizations structure their SOC. We discuss the skillsets required for threat hunting in Chapter 2.

Summary

- The rise of cybercrime has created an insatiable appetite for threat hunting.

- Organizations should apply threat modeling techniques to derive their custom threat-hunting methodology. Frameworks such as MITRE ATT&CK can provide a solid baseline for this.

- One of the fundamental problems with cybersecurity is that organizations often do not realize when they have been compromised. Traditional incident response methods are typically reactive, forcing security teams to wait for a visible sign of an attack. The problem is that many attacks today are stealthy, targeted, and data-focused. Traditional methods of defense revolve around reactive security—waiting for visible signs of a breach and taking appropriate actions in response. Modern attacks are much more advanced and sophisticated. These types of attacks rarely show signs and often go undetected for months or years. Proper threat hunting offers sufficient network visibility to help security professionals detect malicious activity and respond accordingly.

- The Threat Hunting Maturity Model (HMM) helps organizations map their current maturity and helps them set a target maturity to achieve in a reasonable time frame.

- Businesses should assess their need to hunt threats based on risk exposure, and then determine if they have the structure to support this.

- Threat-hunting solutions involve a unique combination of people, processes, and technologies. Organizations put people at the forefront of threat hunting, which means they are supported by robust technology and processes for better visibility into their network. This allows them to detect and respond to malicious activity.