Chapter 3

The Attacker Mindset Framework

The Attacker Mindset Framework (AMsF) is the method and systematic approach for achieving an objective. It's the life cycle model for an attack. The remainder of this book is a support for this framework. By using the AMsF, you become familiar with building strengths like mental agility, objectivity, and critical thinking. Through the use of exercises and stories, you start to think like an attacker.

The AMsF is formed by functionally overlapping elements. The base elements covered here are development, execution, and ethics, which are further broken down into their own primary components. These three groupings are what make up the attacker mentality. With these at play and executed well, you can probably compromise most businesses worldwide with seemingly devastating results. Obviously, if you are a malicious attacker, you will likely forgo the ethics portion and gain similar results but with more risk. As professional, ethical attackers, we cannot afford to execute without ethics.

The good thing about any framework is that it gives you the freedom to apply it differently in any circumstance and for any objective. This framework also allows for individual differences in effort and execution (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Attacker Mindset Framework (AMsF)

Development

The development phase of the attack cycle leans heavily on the first four cognitive skills needed to practice this mindset: curiosity, persistence, information gathering, and mental agility.

There is no attack without information. Likewise, without processing and using the information well and for the good of the objective, the attack will falter. Looking back to the very first example given in Chapter 1, “What Is the Attacker Mindset?,” where a woman spilled hot coffee on herself and I thought, I bet she was going over a bump! instead of Oh, she should sue!–information is critical to the mindset and the direction you take as an attacker, and so is how you process it. Had I known that McDonald's was heating coffee perpetually at 180–190° F, and that coffee at that temperature, if spilled, causes third-degree burns in 3 to 7 seconds, I'd have known how to get approximately $3 million in putative damages from McDonald's. I didn't have that information. And more important, I didn't think to look for it. I was not at all curious about the coffee or any information to do with it. I was only focused on the woman. Worse still, I went with what I thought I knew, which is that it's not anyone else's fault if you single-handedly spill coffee on yourself (speed bump or no speed bump). This thought process in and of itself highlights two interesting points. The first is that this is a sort of bias that we all fall victim to and must fight hard not to. It takes a lot not to operate from bias because it is most often invisible to the operator in every way.

The particular bias I was suffering from is known as anchoring bias; I relied too much on one key piece of information and the first piece I received. I also fell victim to the illusion of validity, which meant I overestimated the accuracy of my own perception and judgment. These examples are two of a huge number of cognitive biases that hamper critical thinking and, as a result, the validity of our decisions and stances on things. This neatly plays into the second thing of note, which is that it is always best to get a good picture of both sides of the story—for instance, finding out the temperature of the coffee.

There's another, darker side to be considered with regard to information weaponization for the good of the objective. To explore it, we must look at the world of spies. Ana Montes was a prolific and damaging Cuban spy. But to those she was deceiving, she was thought of as a star. She had been selected, repeatedly, for promotions and showered with honors, accolades, and even a medal from the CIA. One of Montes's former supervisors even described her as the best employee he had ever had.

She was a Cuban analyst, what is known as a GS-14. But she was also on the clock for Fidel Castro for her nearly 20-year career. For the entire time, she passed along secrets about her colleagues, she spied on the American spies working against Cuba, and she leaked classified US military information frequently. Moreover, she manages to blindside her brother Tito, an FBI special agent; her former boyfriend, Roger Corneretto, an intelligence officer for the Pentagon specializing in Cuba; and her sister Lucy, a 28-year veteran of the FBI who has won awards for helping to unmask Cuban spies. Montes never removed any documents from work, nor did she send them digitally. Instead, she kept the details in her head and simply typed them up at home. She would then relocate the information onto encrypted disks, meet with her handler, and turn them over.

But what did she do from an attacker mindset point of view? Well, she stuck to all four laws and used all the skills. Montes most certainly had an end in mind; it was believed to be a shared end between her and her employers and her country to a degree; she weaponized information and applied it to the objective time and time again. She weaponized information she got from being on the inside and applied it to her own objective. She altered other information so that it could not be properly weaponized by those who believed her to be working along with them.

All of that is a given, and it was not easily detectable by her peers because they all thought, and Montes seemed to be, working from the same scope for the same objective. Her real power came from the fact she never broke character. If she had, for even a second, she would've been in jail a lot sooner. Her duplicitous game meant everyone thought she was working for the same goal they were, and because she continuously bent the information to her own objective without breaking character, she was able to deliberately distort the US government's views on Cuba. Her pretext was not for the good of everyone else's goal. It was only to disguise her as a threat from it.

Eventually, though, Montes did break character and took actions that could not be aligned with the mission she was supposed to be working on. In other words, she acted in a way that was not congruent with the American objective. She deviated from the normal course of action and acted in a way that benefited her own objective.

In 2001, an analyst at the National Security Agency (NSA) approached Scott Carmichael, a counterintelligence officer, with sensitive information: the NSA had intercepted and made sense of a coded Cuban communication. It revealed a prominent Washington figure who was secretly working for Cuba. They called this person Agent S and noted that this double agent had interests in the ‘Support for Analysts File Environment’ (SAFE) system and had traveled to Guantanamo Bay in July 1996. (SAFE was the computer system of the Defense Intelligence Agency [DIA]). Carmichael cross-referenced any DIA employees who had traveled to Guantanamo Bay in July 1996, and a familiar name came up: Ana Montes.

Consequently, Montes is in jail at the highest-security women's prison in the nation. She's shared a home with a woman who strangled a pregnant woman to get her baby, a nurse who killed four patients with massive injections of adrenaline, and a former Charles Manson groupie who tried to assassinate President Gerald Ford. Montes took actions that were outside the scope of what was best for her seeming objective, and it was an immediate red flag. Law 4—everything you do as an attacker must be for the good of the objective—will always out a traitor or someone detrimental to the mission because at certain points they will have to choose their true objective over the one they are pretending to act on behalf of.

Stepping out of the world of spies and infiltrators, I come back to information. Information is the lifeblood of any operation, and so knowing how to collect and process it is integral to achieving and using the mindset. In this beginning phase of the attack, you gather information, assess that information, and categorize it into one of three classes: useful from a pretext standpoint, useful for the actual attack insofar as helping to achieve the objective, or not useful at all (to be disregarded). Learning new ways to process, follow, and apply information becomes easier with practice. This is development, and it's the first major piece of the AMsF.

The development of an attack can be split into two subcategories. The first is assessing information, and the second is creating vulnerabilities from it. Achieving this involves processing the information and mental agility.

The ability to assess a business's vulnerabilities through your AMs lens means parsing seemingly innocuous information to help form an attack. Examples of this apparently mundane information are things like job postings for the company that specify particular systems and software used; pictures of office space and lists of upcoming events that employees will attend, or even those that they have attended in the past; and even social media postings allowing insight into the culture of the place. One of the best places to look for information on a company is on sites that allow employees to critique their place of employment. Of course, not all information is seemingly innocuous, but if you happen across information that is crippling (aside from reporting it to your point of contact pretty pronto), you have to be able to use it in a way that's not tactless or revealing about your motives. Examples of this would be finding that the domain controller is on the demilitarized zone (DMZ) or that an employee has accidentally posted a picture with the company credit card displayed. In both cases, you would have to operate with discipline and control. In both cases, you would quickly have to inform your point of contact.

The development stage also involves creating vulnerabilities from information for the same outcome. Usually, development means starting to build a pretext, which is typically the first step in an attack's formation. In the next section, brilliantly titled “Phase 1,” I will look at an example of a case in which a pretext is developed from apparently harmless information.

As a helpful aside so that you aren't blindsided later, I further categorize useful information into two classifications: advantageous and elite. Advantageous information is made up of items that can help us but that can change at any time. An example is a company's leadership, software used, or a vendor. Advantageous data is typically stable, but it's not elite. Elite information doesn't change over the course of its lifetime, unless the company is sold or acquired. Other examples include the company's Employer Identification Number (EIN); its core services, profits, and losses each year; and other historical information.

When we're attacking a person, an example of elite information would be health data, such as blood type and mental conditions. We live in an age of genetic sequencing, whereby the best of current-day science tells us that all humans are 99% alike and that only 1% of DNA accounts for our differences. In other words, your DNA is responsible for your psychological traits and personality; it can reveal your mental illnesses and abilities. Behavioral problems show great genetic influence, too. This puts elite data in a category entirely of its own. With the rise of personal genomics, a person's mental strengths and weaknesses can be predicted from birth. That's valuable information, and it is available to us now as attackers.

Advantageous information would be a person's address and their email. Typically passwords change over time, too.

This level of categorization is not needed, but you might find it helpful to label things this way, depending on how detail oriented you are and if categorizing things this way is beneficial to your client.

Phase 1

The first phase of development concentrates its efforts on sifting through broad and voluminous information without any direction. The searches you perform and the information you gather will obviously pertain to the target, but it won't all be in the same category. As an example, you might collect information on the public appearance of the company, the services they provide, the hierarchy, and other even simpler information, like the address of their headquarters or if they sponsor employee events. Gathering all this information and sorting it into categories will allow you to hone your avenue of attack and gather more information to design and craft a pretext in the second phase of development.

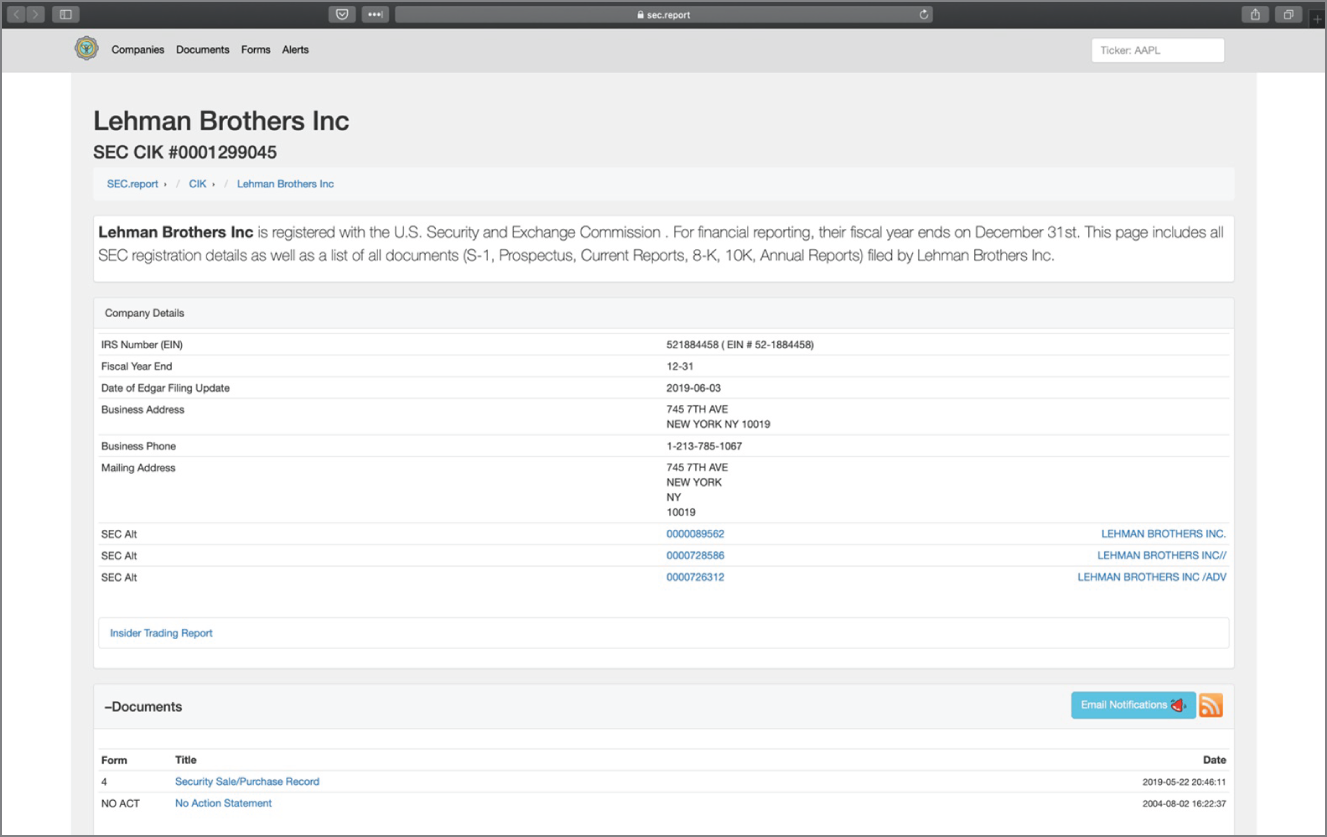

Because I'm never in the mood to be sued, I'll start with targeting the Lehman Brothers, a company I've chosen because they have long since gone out of business. I search Google using the Time Tool, a search function that can collect search results for your query before a certain date, during a date range, or after a date when set. I set it to display information between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2007. I find two items that allow me to begin developing a pretext as if I was building an attack, circa 2002. Notably, this is a very straightforward example, and it showcases the simplest of attack development to get us started.

Finding No. 1 (see Figure 3.2) supplies me with the target's physical address. Eventually, after searching that address, I am taken to Finding No. 2, which gives me information on the building. The same page leads me to a PDF document that includes the architect, engineers, and suppliers of the building (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2 Finding No. 1: Lehman Brothers’s corporate address

SOURCE: https://sec.report

Figure 3.3 Finding No. 3: Lehman Brothers’s building engineers and suppliers

SOURCE: www.emporis.com

From here I have a few choices. I hesitate in choosing which line to follow first. If I could impersonate the elevator supplier or engineering company representative, I'd probably have free access to the whole building. But pretending to represent the facility management company would also gain me a lot of freedoms and cover. Because of this, I start by searching for the facility management company, which turns out to be Hines Interests LP. But ultimately, I choose Otis Elevator—they are well known, and the use of an Otis Elevator UTF fire service key would likely gain me access to any floor I want.

Admittedly this is pretty easy stuff, so I'll provide one more example. This example shows another avenue to a pretext and hints at the volume of information available without even using a Google dork. By using and mixing operators, a Google dork can help a user locate sensitive, buried information that is not well protected. Using these operators, or dorks, a user's searches become advanced searches.

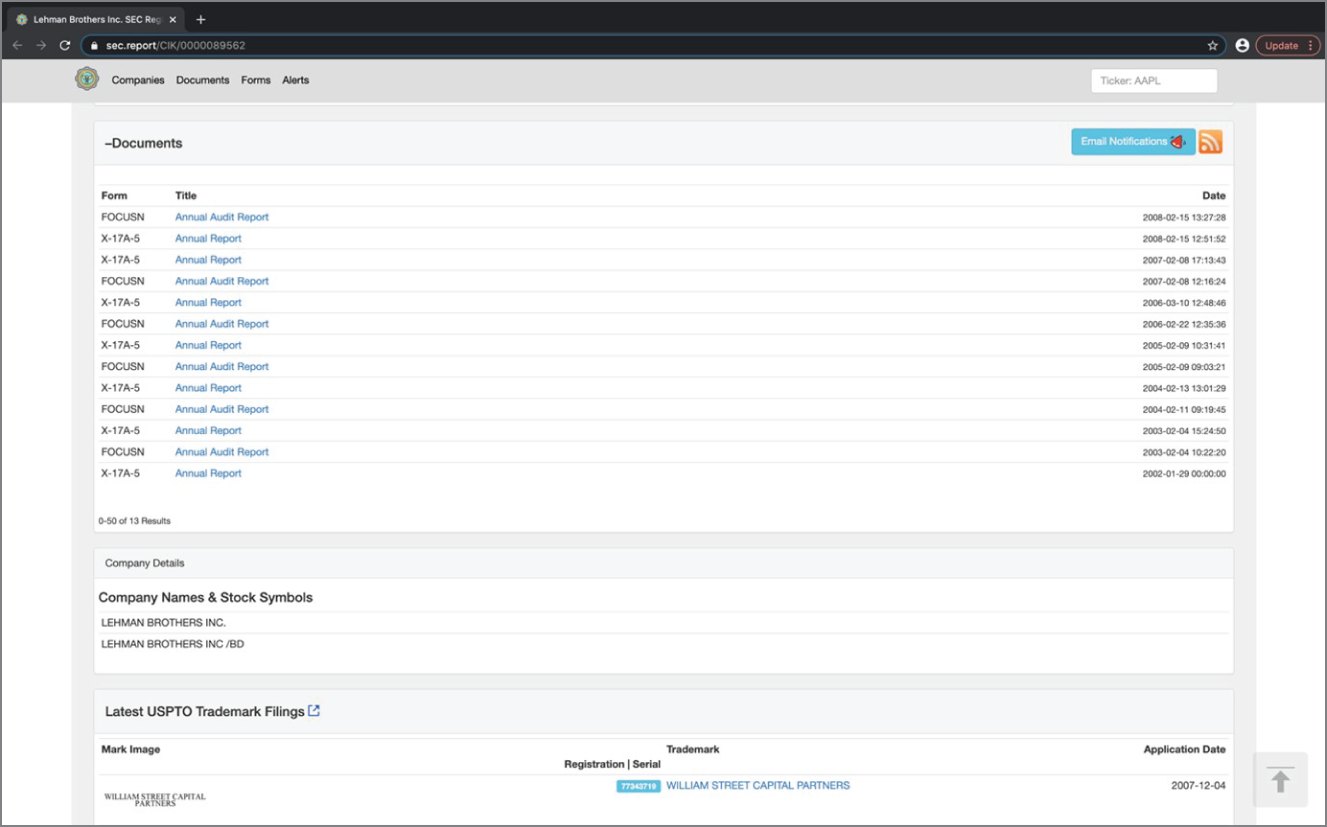

Pivoting slightly from the first search, instead of choosing to search the address of the business, I choose the SEC ALT number, which is the Securities and Exchange Commission number, given as 0000089562.

This search takes me to a page similar to the first search. The page, shown in Figure 3.4, lets me download a document (see Figure 3.5), called a Consolidated Statement of Financial Condition; collect the signature and telephone number of the chief financial officer (CFO); and also ascertain their auditors to have been Ernst & Young (EY).

Figure 3.4 Find No. 1: SEC ALT number

SOURCE: https://sec.report

With these findings, I consider posing as a consultant from EY and spoofing the number of the CFO to bypass reception.

From here, we can move to the second phase of development, which is also split into two.

Figure 3.5 Find No. 2: Ernst & Young LLP

SOURCE: https://sec.report

Phase 2

Before delving into the second phase, let's discuss the two subsections of Phase 2. First, building the two subsections does sometimes happen simultaneously due to the nature of information—when searching for one thing, we invariably stumble onto other information that's not helpful at that exact moment but that might be of use later. Within the framework, gathering this information is referred to as “developing the information in each category” and “combining the information sets.” Ultimately, this means that there's gathering information to support your pretext and there's gathering information to further your attack.

Sticking with the Lehman Brothers example, if I were to build up OSINT to pose as an Otis employee, I'd need a similar uniform and an ID badge; I'd need to know about offices and depots they have; and I'd have to see if I could find any information online about how often they service their elevators. I would also consider calling as an Otis employee to the building/maintenance company to schedule an appointment to inspect the elevators or to try to ascertain when they were last scheduled. I would also want to show up with seemingly legitimate paperwork to support my pretext. This is all OSINT heavy.

For the other subsection, recon development, I would look for information that could bolster my objective. If my objective was to get to their security operations center (SOC), I would look for information on what kind of security doors were in the building, search for building blueprints, and meticulously go through social media accounts to see if there's ever been a photo posted from within the SOC. I'd comb through LinkedIn, searching for the people who work in it.

For both phases, it is fair to say that the real test of knowledge gained isn't in its truth but in its utility.

Application

The development of an attack is the ability to assess any business's vulnerabilities through our AMs lens by parsing seemingly innocuous information or leaked information to form an attack. The application is the leveraging of that information to perform our attack.

Let's look at application from a high level. There are many ways to attack:

- Physical Attacks An attack on a physical resource, such as a facility, building, or other physical asset.

- Human Attack An attack that involves social engineering and the manipulation of people to achieve the objective, also at a physical resource/facility, but usually one with human capital, includes vishing (voice phishing).

- Cyberattacks Cyberattacks can range from installing spyware or malware onto a computer or network to attempting to destroy the infrastructure.

Phishing falls between the latter two categories, with both a human and a technological component.

- Theoretical Attacks Often used for strategy and decision making, a theoretical attack offers companies and organizations fresh perspectives for a hypothetical future. It is typically performed by two opposing teams, generally external to the organization, that test the weight of the intelligence given to them, both arriving at different outcomes based on the same information. This information can be pivotal for decision makers who can then choose a path more easily, especially when the stakes are high.

The second phase of development sees you gather information to realistically mount an attack. Earlier in that section, I said that as an Otis employee, I'd need a similar uniform, an ID badge, and knowledge of typical maintenance schedules they keep with regard to their elevators—maybe because they are required by law or regulation. This type of information feeds the application and execution of the attack. With this information and the other items I've found on them as a company, I could comfortably mount an attack. The comfort, however, isn't just in how much I can seem like an Otis employee. It is also about how I conduct myself in the face of factors that will remain unknown until I walk in the door on the day.

The application of information is powerful, but there's information that will only be available to you on the day, such as the person you're dealing with, their mood, the proclivity for security, and their job role as well as your own effect on them. To steer the odds in your favor, you should employ the following:

- Confidence in Your Character This doesn't mean to say you must act confident. If you are posing as a lost foreigner (hey, it's worked for me before), then you shouldn't really be too confident, but you should have confidence in your “character” or pretext choice.

- Commitment to Your Character You cannot enter as the lost foreigner or an Otis employee or any other and disengage from that character unless planned. This plan, for me, includes if I get caught. I will keep in character for as long as I can until I am sure they will not let me go (obviously I would try again) or if they threaten to call the authorities. If one or both of these occur, I explain the situation and ask for my point of contact to be reached. There is, however, a line. On my first job for my current company, Social-Engineer LLC, I went in as a satellite specialist there to renew a license. I also got someone to let me on the roof to check the equipment. This was overkill. I was in the building, I was getting all the flags required by scope, but I wanted to see how far my character could get me—it was close to a pointless exercise, and the equipment on the roof wasn't in my flag list. However, I offered the information to the client because I wanted to (a) be transparent and (b) show all the weaknesses I found. I said earlier it was close to a pointless exercise. It's useful for the client to know how far you can get. Since it was considered within scope, and the roof hadn't been struck off, I committed to my character too much and essentially did the job of the person I was impersonating.

- The third law states that you never break pretext. This law actually means that you are never yourself. You are always in character. You are always disguised as a threat for the sake of the fourth law: the objective is the central point from which all other moves an attacker makes hinge from.

- Narrative Effect As humans, we love stories. In reality, we don't always see the truth. We rely on a biased set of cognitive processes to get to a conclusion or belief. This natural tendency to view our thoughts as facts to fit with our existing beliefs is known as motivated reasoning—and we all do it.

Though we may see ourselves as rational beings, we are very reactionary. Most of our decisions aren't rational. This is why the application of pretext is important and not only the application of information we have to use against the client. As human beings we're wired to interpret information as confirming our beliefs and to reject information if it runs counter to those beliefs. So if I show up in an Otis uniform and the building has no elevator, that's going to send up a few red flags.

According to Sara Gorman, a public health specialist, and her father Jack, a psychiatrist, “[R]esearch suggests that processing information that supports your beliefs leads to a dopamine rush,” and as we know, dopamine is addictive. On the flip side, information that is inconsistent with one's beliefs produces a negative response. This leads people to see what they want to see so they can believe what they want to believe—so preload them.

Preloading

Preloading is influencing your target before the event takes place. In other words, the attack starts before you've walked in the door—how you walk, how you carry yourself, what you are wearing, and your demeanor, posture, facial expression, everything down to your gait, are all factors in your success—it's all part of the attack. Get people to believe what you want them to, what fits the narrative you're selling, and you will find yourself with an easier target. It's a great way to begin the application phase.

“Right Time, Right Place” Preload

Preloading can work by simply being in the right place at the right time. Imagine you are a target for a moment; you are at a work event and someone approaches you, seemingly interested in you and your job. It doesn't seem too threatening—after all, it's just someone interested in learning about your job and at a place that seems appropriate to do so. Before long you're talking about how you deploy patches or how you store customer information; they are captivated and so curious about it all—finally, a perfect stranger cares about databases as much as you do. Much of this is accomplished through preloading. They were where they were supposed to be and were interested in something that doesn't seem too farfetched, given the circumstances, location, and backdrop. The attacker presented themselves in the right place at the right time.

If, as an attacker, you can preload by merely being in the right environment, half of your job is done for you.

Preloading is one of the best tools at your disposal in the application phase. It does much of the heavy lifting, and combined with your commitment to character, you become powerful as you apply information to gain information—all to achieve your objective.

Ethics

As the good guys, all of what we're learning here is underpinned by something a malicious attacker will never have or use: ethics and morals. Keeping the moral line between us and them and choosing to be bound by ethics is the staple of the mindset I am trying to teach. You can't—and don't—always show it in the moment, since it's the antithesis of our job when in attack mode, but our moral compass wins in the end, when you help rebuild the pieces. In doing this, you make companies, employees, and the public safer.

There is another point of consideration when delving into ethics that I often find myself talking about in speeches I give to agencies and companies alike: believing you're doing the right thing can still make you feel as if you are not. And vice versa—feeling you are doing the right thing doesn't necessarily mean you're actually doing the right thing. Ethics is a field that isn't always black and white.

Intellectual Ethics

To intellectually believe you are doing the right thing will require analysis of the situation on your part. To intellectually believe you're being ethical, you will need truth, knowledge, and understanding. These three things are what distinguish intellectual ethics from the presumption of ethics at play or merely feeling you are operating ethically. The line of ethics is movable; it's decided by the spectrum your target sits on. If you hunt terrorists, you don't have to apply ethics against your target or environment, as professional social engineers often do. You must apply ethics against the greater good. The Innocent Lives Foundation tracks and traces pedophiles. Ethics are not applied against the targets in these cases, either. They are applied against the greater good.

As an attacker, sometimes your job is to deceive people for the greater good, even if they are good people, and ultimately, you will lie for a living. That can chip away at even the most stoic among us. But, intellectually at least, there are different kinds of lying. First and foremost, there's anti- and prosocial lying. If you truthfully understand that, after assessing all the information available to you, you're conducting your actions on behalf of something bigger than yourself in that moment, something that will in the end produce a safer environment for its population, then you can intellectually believe that you are operating ethically.

Prosocial lying requires empathy and compassion because you need to be able to posit that what you say or do may cause harm in the hypothetical future—which is a responsibility that shouldn't be shrugged off easily. But in having a sense that what you do matters, that it is for a cause, not a seemingly malicious act for the sake of it, you should remain intellectually safe.

Reactionary Ethics

I refer to the “feelings” of being ethical as reactionary ethics because they are most often a reflex to a situation relative to you and your beliefs. There are two things that can help you navigate reactionary feelings hinging from a job: the scope and the objective.

If the scope permits your actions, then any negative feelings you have are resolved in the context of your response. The objective is also another indicator of whether the feeling of operating ethically or not is sound. As an aside, choice is something that's included in ethics, and you should always feel you have the choice whether or not to execute. I personally base that decision on the weight of the greater good.

You have a morally ambiguous job as an attacker. It is centered around dishonesty, duplicity, and confidence. As I most often describe the job of attacker, we are the intersection of corporate spy and con artist, at least as social engineers. Network pentesters aren't a stone's throw away from that description, either. Their job is to surveille and exploit. So, where do morals come into play and what's the metric?

The primary moral virtue of an attacker is integrity. Integrity comes from serving and protecting your clients. To accomplish this goal, you must be able to explain your technical and ethical limitations with regard to each contract. Additionally, the only line between an ethical attacker and a malicious one is intent. Your intent is never in question as an ethical attacker—you should never be wondering if you do or do not agree with protecting the client. If you are wondering that, you've probably flipped, and if that were me, I would recuse myself from the project. For example, I know I would never take a job for the Ku Klux Klan. A ridiculous statement, but nonetheless it shows that you won't always agree with your clients’ ethos, and when that occurs, you are not the right person for the job. Say no.

However, your morals cannot stand in the way of you and influencing a target for the sake of the mission. As an example, you cannot be so in love with your client's business that you hold back from trying to beat it. In this case and in these moments, your morals must be applied to the greater good. As attackers, we have to solemnly believe that everything we do is for something bigger than ourselves and winning in that moment.

There's one other nuance to morals that's worth covering: the greater good of a mission, rather than the acts of it, are items to be concentrated on when executing. This guideline is most applicable to those who have a harder job than mine: hunting terrorists, human traffickers, and other such factions. Morals and ethics aren't applied to the targets of these operations and investigations. Our moral psychology as humans dictates that we apply morals to those who are hurt, not those who are responsible for the hurt.

Ultimately, you may have to look at what you are doing through the lens of the consequences that will ensue and see if you can reconcile the two from a moralistic standpoint. Notably, guilt and morals or sadness and morals or any other emotion and morals aren't mutually exclusive, but knowing your intent matters. It gives a sense of meaning to otherwise difficult work.

Moreover, the field of ethics (or moral philosophy) involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior. It is widely accepted that ethical theories can be divided into three general subject areas: metaethics, normative ethics, and applied ethics. We will skip the first and look at normative ethics. For us, as social engineers, we look to the Social Engineering Framework, written by Christopher Hadnagy:

Set out in this framework is The Social Engineering Code of Ethics which accomplishes three important goals: it promotes professionalism in the industry, establishes ethics and policies that dictate how to be a professional SE, and provides guidance on how to conduct a social engineering business. More than this it defines moral standards that regulate right and wrong conduct. It involves articulating the good habits that we should acquire, the duties that we should follow, and the consequences of our behavior on others. The following 10 bulleted points comprise the Social Engineering Code of Ethics:

- Respect the public by accepting responsibility and ownership over your actions, and their effects on the welfare of those in, around, and involved with the engagement.

- Before undertaking any social engineering engagement, ensure you are fully aware of the scope and effects on others and their well-being.

- Avoid engaging in, or being a party to, unethical, unlawful, or illegal acts that negatively affect your professional reputation, the information security discipline, the practice of social engineering, others’ well-being, or the parties and individuals in, around, and involved with the engagement.

- Reject any engagement, or aspect of an engagement, that may make a target feel vulnerable or discriminated against. This includes, but is not limited to, sexual harassment, offensive comments (verbal, written, or otherwise) related to gender, sexual orientation, race, religion, or disability; stalking or following, deliberate intimidation, or harassing materials. Additionally, lewd or offensive behavior or language, which may be sexually explicit or offensive in nature, materials or conduct, language, behavior, or content that contains profanity, obscene gestures, or gendered, religious, ethnic, or racial, slurs are all to be avoided. Employing any of these tactics reduces the target's ability to learn and improve from the engagement.

- Do not negatively manipulate, threaten, or make others uncomfortable in any way, unless specified by a client due to unique needs and testing environment.

- Minimize risks to the confidentiality, integrity, or availability of information of your employer, clients, and individuals involved in engagements. After performing a social engineering engagement, ensure the security of obtained information is a priority. Never disclose information to outside parties as private and confidential information must remain private and confidential. Do not misuse any information or privileges you are afforded as part of your responsibilities.

- When training future social engineers, consider that training will leave a lasting impact on your students and the methodology with which you train will echo through all students’ future engagements. Provide students with the knowledge and tools to create positive learning environments and productive scenarios for their future engagements and clients.

- Ensure the social engineering practices of yourself and your students include conscientious, thoughtful, and considerate ways to escalate engagements to eventually emulate real-world attack vectors. Recognize our clients are seeking ways to improve their security posture and work with them to increase the difficulty of realistic attack vectors.

- Respect that social engineering engagements involve human vulnerability and avoid publicizing vulnerabilities, whether through a blog, social media, or other medium, that result in harmful effects, emotions, or feelings for your client and the individuals and parties in, around, and involved with the engagement.

- Do not misrepresent your abilities or your work to the community, your employer, or your peers. Ensure you have the experience and knowledge promised to your clients and stakeholders.

Refer to the framework at www.social-engineer.org/framework/general-discussion for further insights.

Social Engineering and Security

Switching gears a little, let's look at social engineering in conjunction with AMs because they are closely related. Much of what makes up AMs is facilitated in the real world by using social engineering. Although many social engineering attacks are diverse and dynamic in nature, common patterns emerge when we break down attacks. For instance, social engineering most often uses OSINT followed by rapport building and elicitation of help and assistance themes, which we will delve into later. Some attacks use fear as a theme, and others use greed. Nonetheless, after performing OSINT, social engineers typically rely on their social skills to advance an attack, which is both deceivingly underwhelming and terrifying all at once, that a social engineer may be able to elicit information from a person to create and then exploit a vulnerability should not be ignored. It's the weaponizing of a person who, if effective, can circumvent the most modern and hardened defenses.

There are many forms of social engineering; the main vectors are phishing (email), vishing (voice call), SMShing (text message), and in person (this includes impersonation). As attackers, we need to be able to execute attacks down any and all of these vectors. Network pentesters have to apply the attacker mindset to identify, exploit, and resolve security vulnerabilities and weaknesses affecting a target's digital assets and computer networks, too. Then, in some cases, they must use social engineering to further their attack or hold.

However, this book does not strictly cover social engineering. This book is (obviously) about AMs, and AMs and social engineering are not one and the same; rather, they are relatives. Given that, there's no doubt that social engineering has become a serious occurrence in information security. I often describe it as the intersection of social skill and business stress testing, but what it boils down to is human versus human. As has already been pointed out, social engineers employ certain tactics, like fear, authority, scarcity, and rapport—building techniques, to strengthen their attacks. All of these can prove powerful for an attacker to leverage against their target, but we cannot afford to focus on them here. This is because you can be a social engineer but possess no real form of the attacker mindset; it is neither acting skills nor influential acumen alone that makes an attacker's mindset, although both can be helpful. It's truly the discovery and application of information that forms this mentality.

As I will cover in this book, curiosity and persistence are the driving forces of the discovery of information, but this discovery requires a methodology—a systematic approach to OSINT is therefore paramount. Understanding that data is abundantly available is something I consider to be a strong and optimistic outlook; being aware that you will have to parse large amounts of data efficiently and effectively, and filtering it to the items that are critical for the success of the mission, is a skill that requires self-discipline and an unwavering dedication to the objective at hand. You should always keep in the back of your mind that sometimes you have to apply information to gain information.

The application of information is made easier if the primary step of collecting it is performed properly. Seeing weakness through the lens of the information you are collecting and applying it is the logical extension of the discovery phase.

Social Engineering vs. AMs

Again, it's beyond all doubt that social engineering is a serious discipline with serious consequences. Neglecting to comprehend the nature and power of it over security will only ever serve to decrease the security posture of our organizations. KnowB4.com estimates that 98 percent of cyberattacks rely on social engineering (https://blog.knowbe4.com/social-engineering-is-a-core-element-of-nearly-every-cyber-attack). As a social engineer, my job is to influence others to obtain my objective. But I could do that without any presence of AMs at all. For example, I don't need any real semblance of AMs to make a call, follow a script, and hope that the target unwittingly helps me achieve my objective, but I could still be classified as a social engineer. You can see this lack of AMs in other related industries, such as “script kiddies” in programming and ethical hacking—not having an underlying skill doesn't preclude you from achieving an objective at times.

At the same time, forming an objective and knowing how to collect information and how to apply it to a target to reach my objective—but not being able to make the call, write the phish, or approach a target—would make me a terrible social engineer. I'd be hitting all the AMs targets by about 80 percent, but my execution would suffer. So, social engineering and AMs are closely related but not always mutually exclusive—they do overlap. In fact, they can and should be used in a way that makes them functionally reliant on each other because they are most powerful when used together, not separately.

Not all professional social engineers seem to exhibit the qualities of an attacker; rather, they are readily able to follow scripts and hope for the desired outcome. This way of working directly affects those businesses and people we are trying to secure because often a play-by-play of the attack is offered with limited insight into how to solve for future attacks. I fundamentally believe that the best of all social engineers should have a sharp and effective attacker mindset. Blending social engineering with an AMs will place you in an elite category whereby you can identify, exploit, and explain security gaps. This blend is a massive benefit to your clients, who depend on you to give them more than a step-by-step account of the actions you took to circumvent their defenses. To best protect them, you should be able to give them a comprehensive understanding of their whole landscape as you perceive it, not only how you bypassed some of their defenses arbitrarily.

No business should be without an attacker mindset specialist—not if they want to accurately see themselves as the targets malicious attackers do, yet protect themselves and their customers as ferociously and as comprehensively as they possibly can.

Summary

- Social engineering is a dominant discipline in which influence is used as a method of evading security measures at a human level.

- AMs and social engineering are not one and the same, but they are closely related. By understanding the detailed characteristics of social engineering, you can build an effective AMs more easily.

- All social engineers should be able to think like an attacker because, as previously mentioned, social engineering is involved in 98 percent of cyberattacks.

- Social engineering is a way to use your attacker mindset, not a way to form it.

- How you gather information makes the mindset as well as the direction you take as an attacker.

Key Message

Social engineering is a formidable practice in which persuasion is used as a technique to circumvent security measures and gain information or access to it. You can be a social engineer but possess no real form of attacker mindset; it is the discovery and application of information that forms this mentality. AMs and social engineering are most powerful when used together, not separately.

Our belief in ideals and ethics are what make up a society. If you believe in those and you are defending them, you are working for the greater good. With AMs working for the community, not against it, and with your intentions set toward good, you'll have fewer hard days at work.