Chapter 7

Information Processing in Practice

To talk about how to process information, we first have to talk about information itself. When I talk about information, I mean facts, figures, knowledge, details, evidence, findings, insight, and intelligence. Finding these sorts of information types is most commonly achieved through Open-Source Intelligence, often referred to as OSINT.

OSINT means many things to many people. Its official definition is the practice of collecting information from published or otherwise publicly available sources. These sources include newspapers, broadcasts, official government documents made available to the public, and most often OSINT is reduced to information available online. Of course, there are other ways to gain information that are either not listed in this book or illegal.

However, just having heaps of information on a company or its asset, as examples, is not the final step in your intelligence gathering endeavors. You, as the collector, must be able to scrutinize information for its value in relation to the objective set out.

Now we can talk about information processing. Information processing is how you perceive, analyze, manipulate, use, and remember information. Processing information is as critical as collecting it, and it must be processed strictly through the use of the laws of the mindset, which are:

- Start with the end in mind

- Weaponizing information for the good of the objective

- Pretext can never be broken*

- Every action taken must be in support of the objective

*If you are too early in the process to have a pretext, this takes the form of being in your attacker mindset—being curious, persistent, and acting on behalf of the other three laws.

In this chapter, we look at what reconnaissance is and, broadly speaking, how it is performed. But most importantly, we look at how to make information agile and the power behind your attacks.

Reconnaissance

Good reconnaissance is critical to great ethical hacking and attacking. Reconnaissance is generally the bulk of an attack, which explains why using the four laws of AMs in conjunction is so critical. All the information you gather has to further your attainment of the objective and help you with law 3 (don't break pretext) in particular.

We can then further reduce part of AMs's second law of gathering, weaponizing, and leveraging information to a type of self-discipline. Given that your mind as an ethical attacker (EA) most often is curious, it's easy to commit to the belief that persistence goes hand in hand with curiosity. Self-discipline will keep you safe from the epic time sink of a rabbit hole that leads nowhere. For example, if your job is to get into a data center whose lock cannot be picked, that is guarded by armed guards, that employs 24/7 surveillance, and that is also manned by drones, you will spend time looking in the most obvious places—shift switch times, distraction techniques, and drone information—in an attempt to replicate the design and get your own bird's-eye view, ways to jam the signal, and ways to take over or stop the other surveillance feeds. But you might also look to the sewers, which are most likely not monitored. Cases like this are currently rare but will become increasingly common as the future unfolds.

In a more likely scenario, if the objective is to gather personal data on an executive so that you can simulate an attack directly on them—now a common occurrence in this industry—you will spend a disproportionate amount of time looking for personal rather than professional items. You wouldn't forgo looking at the target's professional life altogether, but you would let it lead you, when and where possible, back to their personal life. If you had to form an attack on an executive based on their professional life only, you would not follow any leads back to their professional life that you couldn't link back to them personally. For example, you would link them only to peers with whom you could prove they had an external relationship.

As an example, I will use myself. I will not use dorks (AKA “Google Hacks”) or too many specialized search terms, but if you are interested, please refer to the notes section on the website where you can catch up on more reading and brush up on more OSINT skills, including dorks. I will move through the example quickly, because it's not an exhaustive show-and-tell of how to search, but merely an illustration of how to stay somewhat disciplined and what information is worth gathering, superficially.

If an attacker were given me as a target to attack, and the scope cleared that attacker to phish, vish, or socially engineer me in person, only using personal information, I suspect it would go something like this:

Google search: Maxie Reynolds

I clicked the first five links on the first page of Google results, as seen in Figure 7.1 and one from the second page of results, as shown in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.1 First page of google search results

By clicking the third search result (twitter.com) shown on the first page of results, I was able to find that I have a dog and a MacBook Pro, as shown in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.2 Second page of Google search results

Figure 7.3 First Twitter find

With enough investigation (looking around the page, checking the comments, or using brute-force Google searches), you could work out the dog is a Pharaoh Hound, which is not a common dog. That information might be valuable, depending on what else you can find. It goes in the first bucket: recon.

Figure 7.4 Further information on Target

Figure 7.4, also shows relevant information. Thanks to it, you now know I was born in 1988—which is always handy information. You know that I am Scottish, which may be valuable used in conjunction with other information. You know that I wrote another book (Would I accept an interview request for this book? Would I accept it via email?) and that I have at least one loose tie to the BBC in Britain. You also know I live in the Los Angeles area (good info for all sorts of attacks). From here you could check Facebook or Instagram to see if you could narrow down an address. If that proved futile, you could check other photos for famous landmarks in the frame and pinpoint my typical movements and even my location.

Case in point, I often run OSINT challenges on my own social media as is seen in Figure 7.5. Recently I posted this photo:

Figure 7.5 OSINT challenge example from social media

From that photo, some 160 people were able to pinpoint my location.

Back to finding an attack avenue: In the case of my workplace's website at the time of writing, as seen in Figure 7.6, which I could then use to reverse search, getting an app or service to do a fair amount of heavy lifting for me. Yandex is especially helpful. Yandex is the most-used search engine in Russia and, in my opinion, is by far the best reverse image search engine, with a powerful ability to recognize faces, landscapes, and objects. At the time of writing, however, there were no valuable leads found with Yandex. So I pivot back to my original find—the page I got the image from.

This is an example of a professional page giving personal information. It also lets you know I have ties to the SANS Institute (Phish from SANS?) and that I used to work offshore with underwater robots (Would I answer a phish from a university or science, technology, engineering and mathematics [STEM] course asking me to take part in an initiative for kids regarding underwater robots? I probably would).

Figure 7.6 Example of professional finding giving usable personal inforamtion

Further investigation into the book could lead you in a thousand different ways. You could contact me looking to do a follow-up for a podcast. For a vish, you could pretend to be a reporter, aiming to get information for an article. You could ask me to verify myself, which isn't the strongest move, but it might work. By getting some security questions out of me, you might gain some valuable information. You could also use this information to approach me as an aspiring author looking for tips (which wouldn't be believable—I'd know you hadn't read the book) and ask for my address to send a copy of your own manuscript to. The podcast's description mentions that I've dabbled in stunts; this is another avenue to explore. You can make certain inferences: I must be pretty fit or must have been quite fit at that time. Was there a specific place I was training? A few searches would tell you that I trained at a popular private gym in West Hollywood. There's another avenue to explore.

You could use this information in a number of ways against me. Picking one would depend on the objective, whether it is to find details, discover sensitive information, or perform a long attack.

So, in under two minutes, with one search and by scanning a few finds, you could've identified three potential phishes and a good amount of detail: my year of birth, nationality, computer type, and ties to large establishments. Most of these, especially the last, have good jumping-off points in which more information could be searched for and tied back to the objective.

This is a light take on what AMs is capable of; it's thought-provoking for the newest members of the community or those who are just interested, and it's probably too superficial for the veterans among you. However, the purpose of the search is not to showcase deft skills that you can learn and perform for your own work; instead, it is intended to show that information can be found anywhere, and nothing precludes a result from being useful—only the objective does.

It's your self-discipline as an EA that keeps you from going down the rabbit hole of “Technical Team Lead” or searching for more information on my consulting with government agencies, because it doesn't follow the objective and you may not have ruled out the possibility of more information that better fits your objective. Only when all else had failed would you resort to those sorts of searches in case there was a hint of a personal artifact.

We return to thinking when there's no hard data. We can make inferences when information lacks definite answers. For example, imagine you could find no personal information on me: I had no social media, not even a LinkedIn profile. All you could find was that I worked for Social-Engineer LLC, but using profession to attack me was against the rules. You could piece together some other information based on my profile. For instance, it looks as though I lived in Australia. A quick search of “Maxie Reynolds Australia” (without quotes) yields the following results as shown in Figure 7.7:

Figure 7.7 Results of a simple search

By clicking in the first link shown in Figure 7.7, you would find that I lived in Perth, Australia, as shown in Figure 7.8. That's noteworthy. You could also infer this by combing through my LinkedIn connections.

I studied at Cranfield University. You could go down that rabbit hole looking to see if they have alumni or speaker events. Reverse-searching the image from the site on Yandex, Tin Eye, or even Google reverse image search will also yield some interesting results.

Honing back in on the original book result, you could find I was promoting it at somepoint and, as a result, was on multiple podcasts and was part of multiple interviews.

You will often have to break information down into bite-sized chunks and probe deeper.

As the fourth law of AMs teaches you, the objective is the central point from which all other moves an attacker makes hinge. In cases when you have time for recon, it's not unusual to spend weeks or months gathering information before even beginning to attempt an exploit, as is true for network pen testing, web app testing, red teaming, and social engineering. But even the third law of AMs applies here, the pre-game: never break pretext. Pretext at this point in time refers to how you should be thinking, and you should always be thinking like an attacker. Break the information into usable chunks to gain more information. Always keep in mind that the attacker mindset is nothing more than taking information in and applying it to an objective. Information is everywhere. Gathering it and applying it through the lens of your objective is the intersection of having an attacker's mindset and using it.

Recon: Passive

In network pen testing, passive recon does not rely on direct interactions with a target system and is therefore far easier to hide. This technique involves eavesdropping on a network in order to gain intelligence, with pentesters analyzing the target company for partner and employee details, technology in use, and so forth. This technique isn't too dissimilar to how passive recon is executed in social engineering and red teaming.

Passive reconnaissance is when you gather information about the target without actually “touching” the target. In social engineering, passive reconnaissance would include searches like the one I just described and move all the way to the other end of the spectrum, whereby you would comb accounts and movements, piecing together the life—or at least one aspect—of the target's life. There are no direct interactions with the target when you are passively gathering information. This includes using accounts that do not belong to you and attempting to stay anonymous online. There are many reasons people want to remain anonymous online. Some people want their personal details to remain unknown; some people want to voice opinions that would perhaps negatively affect them if they were to voice that opinion freely as themselves. Whatever the reason, anonymity online is important to many people for many reasons.

Working with the Innocent Lives Foundation, an organization that attempts to bring pedophiles to justice, and the National Child Protection Task force, which focuses on time-sensitive cases around human trafficking, child exploitation, and missing persons cases, we often use passive information-gathering techniques. Here, staying anonymous is of the utmost importance. Virtual private networks (VPNs) and virtual private desktops are employed; using my own accounts would be catastrophic. I apply the same principles to my day job at times. Passive recon means not touching the target, but it also should mean not leaving a trace. I like to take the opportunity to act like a malicious attacker whenever I can, and a good attacker rarely wants to leave a trail of evidence pointing toward themselves. This means employing a sock puppet, or sock, account. It's a pseudonym or persona used for some sort of deception. Some sock accounts are developed and hard to spot. Others are pretty transparent, as if not trying at all to be inconspicuous. But a sock account doesn't have to leave someone believing it's real; it just has to stop them from finding out who is behind it. There is much you must consider when trying to navigate the Internet anonymously.

Creating these covert accounts is indeed becoming harder on many popular platforms, such as Facebook and Instagram. However, there are some loopholes left, but possibly not for long, so my advice is to create as many sock accounts as you can now.

My least favorite platform to create a new account on is Facebook. You will be prompted for a cell number, among other information) and VOIP numbers will not work. The best way around this, at the time of writing, is to clear your cache and log out of all accounts; connect to Facebook without the aid of any IP address masking service employed, but instead of surfing to facebook.com, instead head to m.facebook.com (the mobile version of the site) and create an account from there. As we browse the Internet, we “leak” information. When it is vital that we remain anonymous, there are certain things we must hide:

- External IP

- Internal IP

- MAC address

- Internet service provider (ISP)

- General geolocation

- Operating system

- Browser type and version

- Language we use

There are many steps you can take: you can employ sock accounts, turn off tracking, change privacy preferences, make use of VPNs, turn off logging, or buy servers and services around the world with prepaid credit cards or Bitcoin, for example.

You must also make sure that, even when you're on a VPN, your computer doesn't contact your normal DNS server. Your ISP could leak your host IP if they deploy a proxy to redirect your traffic back to their DNS server. Newer Windows operating systems have a built-in feature called smart multihomed name resolution, which makes it very easy for DNS leaks to appear. To protect yourself you can choose among a multitude of solutions, but they must be applied against the corresponding issue. For example, if your ISP deployed a transparent proxy, its job is to hide in plain sight and intercept your traffic, leading DNS requests back to the ISP's DNS server. The only way to avoid this leak is to block the proxy on your VPN's side.

You may employ your own proxy. A proxy is a widely used solution to attempt anonymity online. It is meant to hide the IP address. Various proxy solutions are available, such as web proxies and software proxies. Basically, a proxy will redirect traffic to the destination from some other IP address.

Interestingly, a search engine can be used as a proxy. Google has a feature called Google Translate that allows users to read web content in many other languages. By browsing a site through this feature, you can use Google as a proxy. This is often not applicable to day-to-day OSINT investigations, but it's worth mentioning for those rare occasions where you'd find it helpful.

Finally, for OSINT operations, I choose Firefox. It is a browser that has enhanced security and a feature called “add-ons” that are often critical in making investigations easier—add-ons like Firefox containers that isolate your searches. These containers are similar to normal tabs, except that each one has access to a separate piece of the browser's storage which means you can be logged into multiple Facebook accounts at once, as an example, because data between the tabs is not shared. The proxy you choose will have to fit your requirements. Check out the notes section of this book for further information. In addition, passive reconnaissance can include DNS and SNMP mining, dumpster diving, a drive-by of the premises, use of social media such as Facebook and LinkedIn, and of course, Google dorking, among other techniques. When considering a drive-by of an organization, you should contemplate their security cameras and things like how your vehicle fits into the area. If you are going to Detroit, Michigan, and into a low-income area, be sure you don't rent a luxury car. Things like this are seemingly inconsequential, but they might matter in the long run. Other things that matter in passive recon are how you are dressed, when you show up, and how many of your team members show up.

Additionally, when creating a covert account to remain anonymous or when you're impersonating someone, you must use a clean email address for your accounts. Every social media network requests that you provide an email address in order to sign up for an account, and using one that's already an established email address leaves you at risk of being tracked. Michael Bazzell talks about this throughout his 8th edition of Open Source Intelligence Techniques: Resources for Searching and Analyzing Online Information (independently published, 2021). In it, Bazzell notes his preference is to create a free email account at a provider like Fastmail (fastmail.com), a unique, established provider that does not require that you provide an established email address in order to set up a new email address. He also notes that these providers are “fairly off the radar” of bigger services like Facebook, and so undergo less scrutiny from them when looking for malicious activity.

Finally, I've discussed at length the degree to which information is the lifeblood of any operation. But it is learning how to weaponize and leverage that information that is the key to this mindset. Information is everywhere and can be valuable if your thought process can make it so. A great way to find lots of information quickly that your AMs can then parse and place into one of those three buckets I often talk about (recon, pretext, disregard) is through meta searching. Sending a request to a regular search engine means you are searching that engine's own database. A meta search will allow you to search multiple search engines all at once. Meta search engines send your queries to multiple data sources and aggregate the results. Mamma, Polymeta, and Carrot2 are all solid examples. Carrot2 is a cluster engine, meaning it takes the results it finds and (usually) categorizes them for you. Mediainfo is a utility that displays hidden metadata within a media file. ExifTool is an application for reading, writing, and editing meta information in a wide variety of files. It's easy to use from the command line and should not be overlooked.

Recon: Active

Active reconnaissance is information gathered about the target by actually interacting with them or, as we often refer to it, “touching” them. The results of active recon are often much more specific and reliable but also much riskier to achieve. For example, vishing a target within an organization is the equivalent of sniper-style information gathering. If you miss and the target alerts the organization of the shot you took, you risk blowing the operation up or making it harder for yourself later. The same is true if you send a phish to a target and the network catches it or if you aim to socially engineer someone into giving you pointed and valuable information, but they become suspicious—you may make it harder for yourself later. Any time you send a packet to a site, your IP address is left behind; it's the same in person—you will almost always leave a trace.

There's much to think about with active recon. As another example, I would not vish a target directly prior to an in-person attack if I couldn't use an accent. I have a very strong and identifiable accent, and it could be too recognizable. I would use an accent to call, but only one that I was sure I was a natural at.

Many people shy away from active recon, but it has a great value that shouldn't be ignored because of the risk. Rather, the risk should be calculated and analyzed as a cost–benefit—what does it cost to perform, and what's the benefit if it goes right? But also, what's the cost to the operation of performing it unsuccessfully? There are always new, creative collection efforts and exploitation activities bringing data sources, but those efforts and activities can introduce new complexities, too. You have to be able to lend some amount of credence to your findings, especially if the attack hinges on their being true. As an example, finding that a target used PricewaterhouseCoopers as their accounting firm in 2015 by way of a leaked document is somewhat valuable. What would be more valuable is knowing that PwC is still the target's accounting firm. As an ethical attacker you can't call PwC to ask, because they aren't in scope, but you might be able to call your target company to inquire using the right pretext. In cases like these, active recon becomes valuable.

OSINT

The real backbone of recon, for most social engineering attacks, and a cornerstone for network attacks, too, is open source intelligence (OSINT). OSINT is intelligence drawn from material that is publicly available. The tools and capabilities you use are ever-changing and evolving. Because of the changing nature of publicly available information, the current period is widely considered to be the second generation of OSINT. Practitioners recognized that the rise of personal computing in the 1990s would change the face, and indeed function, of OSINT forever.

OSINT Over the Years

OSINT began as a defense-oriented enterprise. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was a wartime intelligence agency of the United States during World War II, and a predecessor to the Department of State's Bureau of Intelligence and Research (INR) and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA).

In WWII, the OSS pored over obituaries in German regional newspapers, pursuing news of important Nazis, movements, equipment creation, and deployment. Images of new battleships, bomb craters, and aircraft were fastidiously gathered and, when assessed together, allowed the OSS to measure the state of its enemy, which is exactly how we use it, too.

It's remarkable how similar the OSS's behaviors are to modern-day OSINT investigation behaviors, notwithstanding computer usage. It's possible to argue that the roots of open source intelligence stretch back nearly a century. Moreover, you could argue that William Donovan's quote, made decades ago, in which he stated, “Even a regimented press will again and again betray their nation's interests to a painstaking observer,” is truer today than ever.

Prior to fighting in World War I, Donovan went to Columbia Law School, where a young Franklin D. Roosevelt was among his classmates. After the war, Donovan had a successful career as an international lawyer, and scarcely missed out on becoming the US Attorney General. During the period between WWI and WWII, Donovan traveled the world as a lawyer, interacting with influential foreign figures and subsequently writing up reports for the US government. It was Donovan's connection to Roosevelt that led to the creation of an intelligence agency in the United States. And his quote still holds up today, among the billions of posts, uploads, shares, and likes, that individuals again and again give away valuable, actionable information to painstaking observers.

At the end of WWII, the Foreign Broadcast Information Service (FBIS) was taken over by the War Department on January 1, 1946. One year later, it was transferred to the CIA under the National Security Act of 1947. By then it was a systematic organization. From this time until the 1990s, the concerns of open source analysis were mainly the monitoring and translating of foreign-press sources.

There are important differences between the first generation of OSINT and the second (current) generation. With the first generation, the collection of material was the bulk of the effort. The FBIS operated 20 worldwide bureaus to allow it to physically collect material. The other function of OSINT at this time was the facilitation of trend analysis.

Today, open source intelligence is defined by the RAND Corporation as “publicly available information that has been discovered, determined to be of intelligence value, and disseminated by a member of the IC [intelligence community].” https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1900/RR1964/RAND_RR1964.pdf. OSINT is information that can be accessed without specialist skills or tools, although it can include sources only available to subscribers, such as newspaper content behind a paywall or subscription journals. The CIA says that OSINT includes information gathered from the Internet, mass media, specialist journals and research, photos, and geospatial information and social media.

Events such as the Iranian Green Revolution in 2009 illustrate how using fresh practices of social media data collection can provide a real-time intelligence picture in an otherwise inaccessible environment. Sometime in 2009, Iran was on the brink of a “Green Revolution”; many of its citizens were protesting against the regime and millions of young Iranians took to the Internet to coordinate their activities, share viral content, and encourage others to join in the revolution. For the first time, the Internet was awash with citizen information about a major political event. Internet use in Iran skyrocketed, as did mobile phone subscriptions. During the first week of the protests approximately 60 percent of all blog links posted on Twitter were about Iranian politics. Networks like Twitter have played a great role in attracting people's attention to this user-generated content. All of this meant that for the first time, any individual with access could mine social networks for intelligence-grade content. Although the protests were ultimately fruitless, it is prudent to look back and regard the Green Revolution as a seminal event in the history of open source intelligence and indeed the pinnacle of second-generation OSINT.

Barely a year after the Green Revolution, revolutions spread across the Arab world. The combination of public anger, smartphones, and social media rocked dictatorships across North Africa and the Middle East. However, the CIA OSINT Center was unable to predict the precise evolution of Internet-based social activism in the Arab world, arguably because government intelligence was consumed with collecting intelligence from the powerful elite.

However, in recent years the United States, United Kingdom, and others clearly have taken notice. According to Cameron Colquhoun in an article on bellingcat.com, titled “A Brief History of Open Source Intelligence,” published July 14, 2016 (https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/articles/2016/07/14/a-brief-history-of-open-source-intelligence/), the US military “destroyed an Islamic State bomb factory a mere 23 hours after a jihadi posted a selfie revealing the roof structure of the building, which is perhaps the most powerful example of the military using OSINT for targeted operations.” In the private sector, you and I most likely and most often use intelligence for corporations that require a predatory eye on the information available on them. Ultimately, whether a civilian or otherwise, the realization that OSINT can make or break operations is a fundamental way of thinking.

Finally, as well as the challenge created by the sheer magnitude of information available, and the limited computing ability and other resources we have to parse in real time, government agencies, police and spies, and OSINT practitioners face the growing trend for users to livestream content. This presents very real challenges for all of us. Machine learning, virtual and augmented reality, and artificial intelligence will eventually transform OSINT into its third generation.

Intel Types

I feel it is prudent to also list in this section the types of intelligence, or intel, and some subcomponents. Again, you will have to go hunting for more information on each type to satisfy what information this book must skip over.

Perhaps lazily, I call it all OSINT, but that is not strictly true. Here are all the types of intel that are relevant currently and likely enduring, with broad descriptions:

- Human intelligence (HUMINT) is the collection of information from human sources. The collection can be done openly, such as a police officer interviewing someone, or it may be done through clandestine or covert means (spying).

- Signals intelligence (SIGINT) refers to electronic transmissions that can be collected by ships, planes, ground sites, or satellites. Communications intelligence (COMINT) is a type of SIGINT and refers to the interception of communications between two parties.

- Imagery intelligence (IMINT) is sometimes also referred to as photo intelligence (PHOTINT).

- Geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) is the analysis and visual representation of security-related activities on the earth. It is produced through an integration of imagery, imagery intelligence, and geospatial information.

- Open source intelligence (OSINT) refers to a broad array of information and sources that are generally available, including information obtained from the media (newspapers, radio, television, etc.), professional and academic records (papers, conferences, professional associations, etc.), and public data (government reports, demographics, hearings, speeches, etc.).

One advantage of OSINT is its accessibility, although the sheer amount of available information can make it difficult to know what is of value.

Alternative Data in OSINT

There are four popular types of alternative data, which can be defined as data that is drawn from non-traditional sources. Alternative data is useful when used in conjunction with traditional data sources, like those we've already talked about throughout this book.

- Web Scraping This is the most widely used form of alternative data, according to research firm Greenwich Associates. Types of web-scraped data in high demand include job listings and employee-satisfaction rankings, which can offer clues to a company's growth prospects and internal activities.

- Satellites and Aerial Surveillance Satellite images can be used to count cars in parking lots, a potential source of insight into activity and peak periods. Satellite and other types of aerial surveillance data are best supplemented with other types of data able to provide more detailed estimates of actual foot traffic when it comes to gauging retail sales. Satellites are also used to track ships, monitor crops, and detect activity in ports and oil fields.

- Sentiment Social media feeds, newsfeeds, corporate announcements, and other items are monitored and analyzed for clues to the sentiment of the company and its employees. Watching who in the company unfollows ex-employees on their social media gives insight into how the employee left. This is sometimes very useful information.

- Financial Intelligence (FININT) Information about the financial capabilities of a target is gathered. Detecting financial transactions is a rich source of information. Even if you find out about a transaction weeks or months after, if it is big or important enough, it may not be out of the realm of what is normal for a company to communicate about, such as services, tax, and refunds.

- Tech Intelligence (TECHINT) Intelligence on equipment and material is gathered to assess the capabilities of the targets.

My last note on alternative data is controversial, only insofar as there is disagreement on whether or not FTP data is alternative or not. Either way, it is useful, so I don't want to get caught up in the taxonomy. FTP stands for File Transfer Protocol, and searching FTP servers is one of the most underutilized, underrated activities undertaken by investigators. There are simple Google dorks that exist that will allow you to perform a search. Most often I use “inurl:ftp –inurl (http | https) [company name]” without the quotation marks. Another option for searching for FTP servers is Global File Search (www.globalfilesearch.com).

Signal vs. Noise

The word signal is a representation of the patterns and meaning that are hiding in data that is transmitted. In electronics, signals must be separated from noise to be useful. In OSINT, it's no different; the signal is the information you should follow. The noise is the tidbits of information that will not be useful to you. In the age of big data, there's often more noise than ever when investigating a target and so more challenges in isolating the signals.

With that in mind, how do you go about filtering the signal from the noise? First of all, there's no “cheat”; you have to bear in mind—always—that no stone can go left unturned. The separation of signal from noise is often used in vetting the myriad sources available and evaluating them efficiently. There are categories that should be staples of your searches, like these:

- Data breaches and leaks metadata search

- Search engines

- Social media

- Online communities

- Email addresses

- Usernames

- People search engines

- Telephone numbers

- Online maps

- Code search

- Documents

- Images

- Videos

- Domain names

- IP addresses

- Government and business records

- Geospatial research

Much of this is easily verifiable, which is the first step in knowing when to stop. If you come across something that is not verifiable but that you think matters, you must “add things up,” or infer, as we talked about earlier. In doing this, information will become more than the sum total of its parts in cases. You must then try to verify your inferences, but it's the quickest route to putting information into one of our three buckets as is shown in Figure 7.9.

To truly separate signal from noise, there are a few steps you can take that should become second nature. Stephen Few wrote a book called Signal: Understanding What Matters in a World of Noise (Analytics Press, 2015). Few has written more than a couple of books (some would say he's written a few books, pun intended) on harnessing visualization to help in analysis. In Signal, he takes a broader viewpoint, focusing on the idea of “sensemaking,” which is different from analytical thinking. Sensemaking involves imagination and a healthy tolerance for taking leaps where there is no information to support your route. Upon taking these leaps, you will eventually land at a theory you can then assess and research. The two types of thinking—sensemaking and analytical—are necessary for separating signal from noise where some items remain unverifiable. One will help you navigate a cluttered information landscape, and the other will stop you getting lost down one track. It is easy to think of these as lying at opposite ends of a spectrum of thinking styles, but a blend is often a good way to approach OSINT inference. I typically start by using an analytical approach and then move to sensemaking, although the sequence doesn't matter if the outcome ends up being the same.

Figure 7.9 Buckets: Categorizing OSINT Findings

You should keep in mind that everyone great started out as someone new. It's imperative that I do not further the false narrative that only people “gifted” with some set of intangible skills will be good at untangling signal from noise. This is not the case—I am merely stating that experience helps.

Finally, OSINT relies on search terms plus the information available. If you don't change the language to suit your country, state, city, or demographic, your searches will not be as effective and efficient as they could be. I often use I Search From (isearchfrom) if I want to search Google within a version specified for another country. You choose the country and language and the tool does the rest of the leg work for you. This is especially helpful if you have an international target. It is also great for news articles from the selected country that would otherwise be buried in US Google results.

Weaponizing of Information

There is one more question to ask about vulnerabilities: can you really create a vulnerability where there was none? Good news: in short, the answer is yes. A vulnerability doesn't always have to be identified in the firmest sense of the word. Sometimes we, as attackers, have to turn information into a weapon to fully form a vulnerability. We can weaponize information.

Note that the word information here is that of visual and sensory as well as data or typical information (data). The attack surface is all the ways that an attacker can affect the target. If your target has not been able to map their surface and defend against it wholly, there your true value as an EA lies.

As you have seen, OSINT has evolved with speed and power, and it will not stand still now. Technologies will continue to expand and ultimately enhance OSINT practices. With billions of posts, images, streams, records, and data uploaded to the Internet every day, an abundance of intelligence is available. As previously described, individually, this data would be of little value, but collectively it can lead to important insights. The open source intelligence cycle contains four key steps: collection, processing, exploitation, and production. What you can infer and analyze from data is often as important as the raw intelligence itself. Social network analysis, geospatial context, and often metadata to create meaningful intelligence are of the utmost importance. This process will require your curiosity and persistence if it is to pay off, though, given how cyclical the process can be. However, the payoff is often high—for instance, the intelligence community has been able to use geotagged social media posts to track down Islamic State fighters; the messaging itself was secondary.

The information environment can be generally categorized along both technical and psychosocial dimensions. This is why cybersecurity's primary concern with purely technical features—defenses against denial-of-service attacks, botnets, massive intellectual property thefts, and other breaches that typically take advantage of security vulnerabilities—is lacking and precisely why we need more critical thinking and AMs for defensive measures. The technical view is too narrow. As an example, the April 2013 Associated Press Twitter hack was performed with very little technical prowess and a lot of attacker mindset. In this attack, a group hijacked the news agency's account, putting out a message that “Two explosions in the White House and Barack Obama is injured.” With the weight of the Associated Press behind it, the message caused a drop of roughly $136 billion in equity market value over a period of roughly five minutes. This attack exploited both technical (hijacking the account) and psychosocial (understanding market reaction) features of the information environment.

Another attack, exploiting purely psychosocial features, took place in India in September 2013. The incident began when a young Hindu girl told her family that she had been verbally abused by a Muslim boy. Her brother and cousin reportedly killed the boy. This action prompted clashes between Hindu and Muslim communities. Fanning the flames of violence, a video was posted of a gruesome act in which two men were shown to be beaten to death. The video was accompanied by a caption that identified the two men as Hindu and the mob as Muslim. It took 13,000 Indian troops to put down the resulting violence. It turned out that though the video did show two men being beaten to death, it was not the men claimed in the caption; in fact, the incident had not taken place in India. This attack required no technical skill whatsoever; it simply required a psychosocial understanding of the place and time to post to achieve the desired effect.

With AMs, if something can be used for good, it can be used for bad, and vice versa. There is nothing good or bad, but your attacker mindset will make it so. As an attacker, you can weaponize information for the good of the objective and, ultimately, for the good of the target, who can then attempt to de-weaponize it and gain a new and helpful perspective for how information is gathered and can be used.

In any case, what should be clear by now is that information is the lifeblood of the attack. There is no attack without information. Behold the two stages of open source intelligence through the lens of the organized, ethical attacker: there's OSINT before the objective, and there's OSINT after the objective. There is no single playbook for OSINT; most pentesters have their own methods and preferred tools. Most often, though, OSINT starts with manual reconnaissance and reading up on the target subjects, including using nontechnical sources such as an organization's annual report, financial filings, and associated news coverage, as well as content on its websites and YouTube and similar services. How this unfolds is a mechanism of the second law of AMs, which states that everything you do (and collect) must tie back to the objective.

Tying Back to the Objective

In Chapter 3, “The Attacker Mindset Framework,” I talked about two categories of development. The first, recon development, involves looking for information that can bolster your objective. If the objective is to get to the target's SOC, you look for information on what kind of security doors were in the building; search for building blueprints; meticulously go through social media accounts to see if there's ever been a photo posted from within the organization; and comb through LinkedIn, searching for the people who work for the organization and for job titles, locations, and schedules.

The second category I talked about was pretext development. Pretexts are dependent on the obstacles you have to get around and the type of establishment you are going to. If I were to build up OSINT to pose as an elevator maintenance person, I'd have to find information to support the pretext. I would need the elevator supplier/manufacturer uniform and ID badge, and I would need to know about offices the maintenance company has. I would also want to show up with seemingly legitimate paperwork to support my pretext.

This is all OSINT heavy.

These are two separate avenues of OSINT that eventually converge but ultimately need separate collection and analysis. In both cases, all information must tie back to the central objective.

We've now looked broadly at OSINT, taking into consideration its roots and evolution. However, honing in on OSINT and its everyday functions is the start and lifeblood of every operation. Every campaign and engagement I have been involved in, with every company from the United States to Australia, has started with OSINT. Our team does not go on a job without extensive OSINT, and we go through that OSINT with a fine-tooth comb daily on the run-up to make sure we've missed nothing and that everything we are using from it is in scope. We allow that OSINT to be ripped apart with no form of ownership attached to it. There's no room for personal emotion in OSINT on this level. If the intel isn't good, then it needs to be scrapped. This means that the collector has lost time and the engagement has lost time. That's the nature of OSINT. If there was a perfect way to perform OSINT or any type of intelligence technique whilst ensuring you were on the right path, then companies probably wouldn't need us.

OSINT is our most valuable tool; it often has no cost but that of time, which, overall, is well spent. The thing that non-attacker/members of the public often don't understand is that information doesn't have to be secret to be valuable. What most of us in the information security community call operational security, or OPSEC, the public deems almost valueless as private information. People publish dates of birth, hobbies, interests, and vacation times as if they can't be used to help break into their bank account, house, or other accounts. Businesses publish updates on their sites constantly in a bid to keep their customer base informed, not always realizing that an attacker with a finely tuned AMs is easily able to use that information against them. Given how many of us use the Internet and, in particular, forums, online communities, and social media sites, we can cheerfully and optimistically approach outlets confident there's an employee within our target company who has posted something valuable. But do note that not all online communities and forums gets indexed by search engines, so you may have to independently search these types of sites based on previously collected information on your target to see if they have posted there.

Taking advantage of information found can be as simple as asking for help for a product they use. Searching job postings from a company may also be advantageous. Such postings may ask for candidates with special skill sets, such as “expertise in Python.” None of this is groundbreaking stuff. You can read more about this topic in many books dedicated to OSINT (see the notes section for some of those books). What's novel is looking at OSINT through the lens of AMs.

There is a technical pursuit of OSINT, too. I recommend tools like SpiderFoot, Recon-NG, Google Earth Pro, and Sherlock and Maltego.

In addition to scanning web page content, SpiderFoot looks at HTTP headers, which can ultimately produce OS and web software names and version numbers. This information can prove vital, should you find out that an older version of Windows, Apache, or PHP is being used and exposed on the Internet.

There are many OSINT databases, which makes it possible to search a software version against a known vulnerability database, and then work out the details of leveraging the security hole. Recon-NG is a favorite of mine. It's a full-featured web recon framework. It has plenty of features, such as domain name discovery and credentials gathering, to repository scrapping with additional integrations like Masscan.

Maltego is both a data management and visualization tool as well as an OSINT tool. It's quite complex and cannot, in my experience, be learned intuitively. It is extremely powerful, though. It offers two types of recon options: infrastructural and personal. Infrastructural recon deals with the domain, covering DNS information such as name servers, mail exchangers, zone transfer tables, DNS-to-IP mapping, and related information. Personal recon deals with information such as email addresses, phone numbers, social networking profiles, and even mutual friend connections. It is a very sophisticated tool.

Sometimes, even a technical pursuit can start with OSINT and will maintain a pure level of AMs throughout. This is why OSINT pays off. I won't say you need to devote weeks to OSINT, but even a few minutes can count when you don't have much more time than that to spend.

Finally, there will always be people who leave the rest of us in the dust when it comes to searches, dorking, and using the tools. Being able to collect OSINT proficiently is a valuable skill to have. However, anyone can learn to do it. That sort of technical technique can be taught if you want to learn. The bulk of AMs, as applied to OSINT, however, lies in one area: the ability to analyze information for its value. This can only be done by applying everything you find to the objective and evaluating it through that lens. But more than that, applying AMs to OSINT means the ability to twist that information to fit the objective. How a piece of information gets you closer to an objective won't always be clear, but with a finely tuned AMs, you can see the value in most information. In other words, you must learn to critically evaluate information and apply it (or disregard it) based on your objective. Instead of being burdened by the amount of information you will collect, you will be able to rank it as you come across it. This concept may seem abstract, so I will supplement it with an example.

Let's start with an easy task. Say I want to write a spearphish and all the information I have on the target is his email address and that he went to Colgate University. I can write a phish from the university asking him to give a commencement speech or citing something about the alumni, or even asking him to be part of a mentor program, which I could tailor to his job if I knew it. It's a spearphish, so it would have to be quite warm and personal, using his name, injecting it with any other relevant details, or using a sense of familiarity.

Even easier, if his CV (curriculum vitae) is online, whether it be on LinkedIn or on his own site, it will likely list his “expertise,” which I can bend to my objective. It might have metadata attached that will give me insight to the type of system he is using, which I might be able to leverage in a seemingly technical phish.

If this target has no information available online but a family member does, I would potentially be able to use this. For instance, knowledge about a vacation might allow me to email as the hotelier about the bill or items left behind if the scope permitted and if it was aligned with the objective.

Another thing that will need careful analysis when considering information directly from the target is the use of language. I can extract information from social opinion to emotion by studying his use of language, i.e., how articulate and balanced his communication seems, as well as intensifiers and indications of his stress level. I can thus begin to build a picture of my target that I can work with. This last point illustrates one of the shortcomings of OSINT: misinformation. Operating off false information is harder than operating off no information.

OSINT is valuable and becoming more so every day because now everyone is interested in the findings and has learned to apply them to their role and business interests from IT and security to boardrooms. This is because OSINT is effectively the start of the foothold. The beginnings of gaining access to a company is gaining information about it, and if you can gain enough information to list assets, operations, to profile a company accurately or to circumvent security and other defenses, then you come that much closer to achieving your final objective—whatever that may be.

Figure 7.10 Determining the location of my target by photo

Twitter: Julia Bayer / @bayer_Julia 1

Let's move to a slightly harder task. Imagine just having one photo with little information, but it places a target at a location. The poster of this image, Julia Bayer, simply asks that you work out where the photo was taken (see Figure 7.10).

Let's say I know the target lives in Berlin and looking at her online profiles, this seems easy to infer. I queried Wikipedia and “churches in Berlin.” Without knowing if this image was that of a “former place church” or a current “place of worship”, I clicked on the latter and got to what turned out to be the correct list (Figure 7.11).

The spire from the first picture (Figure 7.10) strongly resembles one from the Wikipedia page. The name given for it is Sophienkirche.

Figure 7.11 List of churches in Berlin

Figure 7.12 Result of Google Maps search

A quick Google Maps search shows trees and surroundings (Figure 7.12).

This gives me hope I am on the right track.

Then I try Google Street View but have no luck. Probably user error. So, I return to the Google Image search. I've found photos of the church, which are a match for the one posted by Julia (Figure 7.10). I can match the photos by the windows, spire, and roof color from Figure 7.10 with Figure 7.13 (below) for a quick pairing.

In a darker example, here's a Europol crowdsourced, brilliant example of geolocation, which I read about on Bellingcat and subsequently asked for permission to retell in this book.

Since 2017, Europol has been crowdsourcing intel and insight for their “Stop Child Abuse—Trace an Object” campaign.

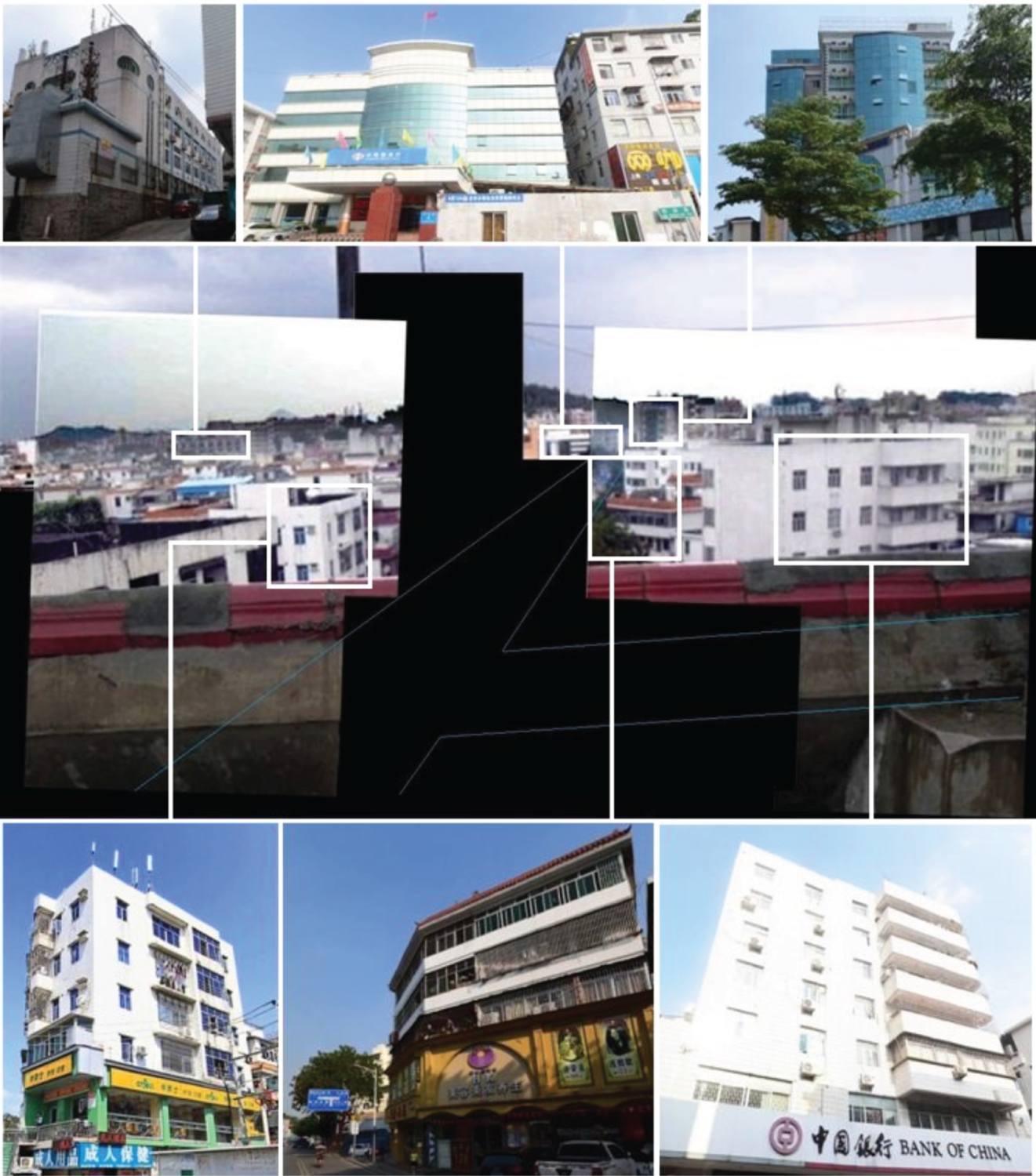

Europol shared new images via their website and Twitter on October 15, 2018. A few photographs were taken outside and made it possible to use geolocation because of recognizable landmarks. Two of these photos, taken from a roof of a building, show concrete buildings and were presumably taken in an Asian city (Figure 7.14). The photos are heavily censored due to the sensitivity of the material. Europol's investigators needed the location of the photos to be able to trace a child abuser and save the victim.

The photos don't seem to contain many recognizable landmarks. There's no text or signage displayed on the buildings, and the concrete structures don’t reveal much of anything.

Twitter user “Bo” contacted Bellingcat and mentioned the architecture showed similarity to the city of Shenzhen in southern China. Bellingcat responded to Europol's tweet with this information and included a photo of similar architecture and an overlay image of the two photos, noting the blue road sign and a structure similar to a satellite receiver on top of a building shown in the photos.

Figure 7.14 Two photos from an Asian city

A short while later, Twitter user Olli Enne from Finland geolocated the exact location of the photos in the Bao'an district of Shenzhen. According to Olli, the images were taken from the roof of a building with coordinates 22.722917, 114.053194. He showed several buildings and a hill in the photos that matched the buildings visible in satellite imagery. Also, a view line across a building with a blue roof to a building with arch shaped windows in the distance lines up with the view line in satellite imagery.

Figure 7.15 Map showing satellite imagery

In later tweets, Olli explained that he searched in Shenzhen and other major cities in China for several hours (note the timeframe—not everything you search for will take just minutes of work). You will need curiosity and persistence in abundance at times. Over this time period, he was looking for little green hills and road shapes, and he drew a map of how the area would look in satellite imagery (Figure 7.15).

The geolocation of the photos could not be immediately verified by Bellingcat because matching the buildings in the photos to the buildings visible in satellite imagery was difficult. However, thanks to Baidu Maps, a Chinese web mapping system, Bellingcat was able to verify that Olli's geolocation was a perfect match (Figure 7.16).

A Google Earth 3D view of the building the photos were taken from shows the same mountains. In particular, the shape of the mountain on the left side of the photos is very similar to the shape of the mountains in the 3D view (Figure 7.17). A smaller mountain with a relatively high peak is more difficult to spot, but following a view line in the photos from the location where they were taken in the direction of that mountain shows the same buildings in the 3D view that are visible in the photos in that view line. Also, the partly visible small green hill at the end of the road is clearly visible in Google's 3D view.

Figure 7.16 Building match

The Bellingcat article goes on to talk about many more interesting and relevant items in its article, including more initial research and how they estimated the year the photographs were taken. You can find the article here: https://www.bellingcat.com/resources/case-studies/2018/11/08/europols-asian-city-child-abuse-photographs-geolocated.

Figure 7.17 Google Earth 3D view

This example steps away a little from the OSINT and type of recon I started out describing, but it demonstrates the power of some of the most important intel types we can use.

Summary

- Good reconnaissance is critical to any operation.

- In general, reconnaissance is the bulk of an attack. This is why the first, second, and fourth laws of AMs used in conjunction are so critical.

- All of the information you gather has to further your attainment of the objective, and it will help you with law 3 (never break pretext).

- There are technical components to OSINT, especially if you want to stay anonymous.

Key Message

OSINT is only as useful as your mind makes it. AMs is taking in information and applying it to an objective. You have to be able to break information down into critical chunks and perform further searches from there.