Chapter 4

Risk Control, Diversification, and Some Other Things You Need to Know

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding the relationship between risk and return

Understanding the relationship between risk and return

![]() Measuring risk

Measuring risk

![]() Introducing Modern Portfolio Theory

Introducing Modern Portfolio Theory

![]() Addressing the assertion that “MPT is dead”

Addressing the assertion that “MPT is dead”

![]() Seeking a balanced portfolio

Seeking a balanced portfolio

October. This is one of the peculiarly dangerous months to speculate in stocks. The others are July, January, September, April, November, May, March, June, December, August, and February.

MARK TWAIN

A peculiarly good writer, but also a peculiarly bad money manager, Twain sent his entire fortune down the river on a few bad investments. A century and a half later, investing, especially in stocks, can still be a peculiarly dangerous game. But today you have low-cost indexed ETFs and a lot more knowledge about the power of diversification. Together, these two things can help lessen the dangers and heighten the rewards of the stock market. In this chapter, I hope to make you a better stock investor — at least better than Mark Twain.

Risk Is Not Just a Board Game

Well, okay, actually Risk is a board game, but I’m not talking here about that Risk. Rather, I’m talking about investment risk. And in the world of investments, risk means but one thing: volatility. Volatility is what takes people’s nest eggs, scrambles them, and serves them up with humble pie. Volatility is what causes investors insomnia and heartburn. Volatility is the potential for financially crippling losses.

Ask people who had most of their money invested in stocks in 2008. For five years prior, the stock market had done pretty darned well. Investors were just starting to feel good again. The last market downfall of 2000–2002 was thankfully fading into memory. And then…POW…the U.S. stock market tanked by nearly 40 percent over the course of the year. Foreign markets fell just as much. Billions and billions were lost. Some portfolios (which may have dipped more than 40 percent, depending on what kind of stocks they held) were crushed. Many who had planned for retirement had to readjust their plans.

There was nothing pretty about 2008.

In early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit, investors got another taste of how quickly the markets can turn. It wasn’t quite as bad as 2008 or 2000–2002 (between February and March, the Dow lost “only” 37 percent), and it lasted for just a short time, but it was still a shocker.

The trade-off of all trade-offs (safety versus return)

To get to the Holy Grail — a big, fat payoff from your investments — you need to take on the fire-breathing dragon of risk. There simply is no way that you are going to make any sizeable amount of money off your investments without a willingness to get hurt. The Holy Grail is not handed out to people who stuff money in their mattresses or carry their pennies to the local savings bank.

If you look at different investments over the course of time, you find an uncanny correlation between risk (volatility risk, not inflation risk) and return. Safe investments — those that really do carry genuine guarantees, such as U.S. Treasury bills, FDIC-insured savings accounts, and CDs — tend to offer very modest returns (often — especially these days — negative returns after accounting for inflation). Volatile investments — like stocks and “junk” bonds, the kinds of investments that cause people to lose sleep — tend to offer handsome returns if you give them enough time.

So just how risky are ETFs?

Asking how risky, or how lucrative, ETFs are is like trying to judge a soup knowing nothing about the soup’s ingredients, only that it is served in a blue china bowl. The bowl — or the ETF — doesn’t create the risk; what’s inside it does. Thus stock and real estate ETFs tend to be more volatile than bond ETFs. Short-term bond ETFs are less volatile than long-term bond ETFs (I explain why in Part 3). Small-stock ETFs are more volatile than large-stock ETFs. International ETFs often see more volatility than U.S. ETFs. And international “emerging-market” ETFs see more volatility than international developed-nation ETFs.

Figure 4-1 shows some examples of various ETFs and where they fit on the risk-return continuum. Note that it starts with bond ETFs at the bottom (maximum safety, minimum volatility), and nearer the top, it features the EAFE (Europe, Australia, Far East) Index and the South Korea Index Fund. (An investment in South Korean stocks involves not only all the normal risks of business but also includes currency risk, as well as the risk that some deranged North Korean dictator may decide he wants to pick a fight. Buyer beware.)

FIGURE 4-1: The risk levels of a sampling of ETFs.

Keep in mind when looking at Figure 4-1 that I am segregating these ETFs — treating them as stand-alone assets — for illustration purposes. As I discuss later in this chapter (when I discuss something called Modern Portfolio Theory), stand-alone risk measurements are of limited value. The true risk of adding any particular ETF to your portfolio depends on what is already in the portfolio. (That statement will make sense by the end of this chapter. I promise!)

Smart Risk, Foolish Risk

There is safety in numbers, which is why teenage boys and girls huddle together in corners at school dances. In the case of the teenagers, the safety is afforded by anonymity and distance. In the case of indexed ETFs and mutual funds, safety is provided (to a limited degree only!) by diversification in that they represent ownership in many different securities. Owning many stocks, rather than a few, provides some safety by eliminating something that investment professionals, when they’re trying to impress, call nonsystemic risk.

Nonsystemic risk is involved when you invest in any individual security. It is the risk that the CEO of the company will be strangled by their pet python, that the national headquarters will be destroyed by a falling asteroid, or that the company’s stock will take a sudden nosedive simply because of some Internet rumor started by an 11th-grader in the suburbs of Des Moines. Those kinds of risks (and more serious ones) can be effectively eliminated by investing not in individual securities but in ETFs or mutual funds.

Nonsystemic risk contrasts with systemic risk, which, unfortunately, ETFs and mutual funds cannot eliminate. Systemic risks, as a group, simply can’t be avoided, not even by keeping your portfolio in cash. Examples of systemic risk include the following.

- Market risk: The market goes up, the market goes down, and whatever stocks or stock ETFs you own will generally (though not always) move in the same direction.

- Interest-rate risk: If interest rates go up, the value of your bonds or bond ETFs (especially long-term bond ETFs such as TLT, the iShares 20-year Treasury ETF) will fall.

- Inflation risk: When inflation picks up, any fixed-income investments that you own (such as any of the conventional bond ETFs) will suffer. And any cash you hold will start to dwindle in value, buying less and less than it used to.

- Political risk: If you invest your money in Canada, France, or Japan, there’s little chance that revolutionaries will overthrow the government anytime soon. When you invest in the stock or bond ETFs of certain other countries (or when you hold currencies from those countries), you’d better keep a sharp eye on the nightly news.

- Grand scale risks: The government of Japan wasn’t overthrown, but that didn’t stop an earthquake and ensuing tsunami and nuclear disaster from sending the Tokyo stock market reeling in early 2011. Similarly, in 2020 COVID-19 hit most of the world’s stock markets hard — some harder than others.

Although ETFs cannot eliminate systemic risks, don’t despair. For while nonsystemic risks are a bad thing, systemic risks are a decidedly mixed bag. Nonsystemic risks, you see, offer no compensation. A company is not bound to pay higher dividends, nor is its stock price bound to rise simply because the CEO has taken up mountain climbing or hang gliding.

In other words,

- Higher systemic risk = higher historical returns

- Higher nonsystemic risk = zilch

That’s the way markets tend to work. Segments of the market with higher risks must offer higher returns or else they wouldn’t be able to attract capital. If the potential returns on emerging-market stocks (or ETFs) were no higher than the potential returns on short-term bond ETFs or FDIC-insured savings accounts, would anyone but a complete nutcase invest in emerging-market stocks?

How Risk Is Measured

In the world of investments, risk means volatility, and volatility (unlike angels or love) can be seen, measured, and plotted. People in the investment world use different tools to measure volatility, such as standard deviation, beta, and certain ratios such as the Sharpe ratio. Most of these tools are not very hard to get a handle on, and they can help you better follow discussions on portfolio building that come later in this book. Ready to dig in?

Standard deviation: The king of all risk measurement tools

So, you want to know how much an investment is likely to bounce? The first thing you do is look to see how much it has bounced in the past. Standard deviation measures the degree of past bounce and, from that measurement, gives you some notion of future bounce. To put it another way, standard deviation shows the degree to which a stock/bond/mutual fund/ETF’s actual returns vary from its average returns over a certain time period.

Table 4-1 presents two hypothetical ETFs and their returns over the last six years. Note that both portfolios start with $1,000 and end with $1,101. But note, too, the great difference in how much they bounce. ETF A’s yearly returns range from –3 percent to 5 percent while ETF B’s range from –15 percent to 15 percent. The standard deviation of the six years for ETF A is 3.09; the standard deviation for ETF B is 10.38.

Predicting a range of returns

What does the standard deviation number tell you? Let’s take ETF A as an example. The standard deviation of 3.09 tells you that in about two-thirds of the months to come, you should expect the return of ETF A to fall within 3.09 percentage points of the mean return, which was 1.66. In other words, about 68 percent of the time, returns should fall somewhere between 4.75 percent (1.66 + 3.09) and –1.43 percent (1.66 – 3.09). As for the other one-third of the time, anything can happen.

TABLE 4-1 Standard Deviation of Two Hypothetical ETFs

Balance, Beginning of Year | Return (% Increase or Decrease) | Balance, End of Year |

|---|---|---|

ETF A | ||

1,000 | 5 | 1,050 |

1,050 | –2 | 1,029 |

1,029 | 4 | 1,070 |

1,070 | –3 | 1,038 |

1,038 | 2 | 1,059 |

1,059 | 4 | 1,101 |

ETF B | ||

1,000 | 10 | 1,100 |

1,100 | 6 | 1,166 |

1,166 | –15 | 991 |

991 | -8 | 912 |

912 | 15 | 1,048 |

1,048 | 5 | 1,101 |

It also tells you that in about 95 percent of the months to come, the returns should fall within two standard deviations of the mean. In other words, 95 percent of the time, you should see a return of between 7.84 percent [1.66 + (3.09 × 2)] and –4.52 percent [1.66 – (3.09 × 2)]. The other 5 percent of the time is anybody’s guess.

Making side-by-side comparisons

The ultimate purpose of standard deviation, and the reason I’m describing it, is that it gives you a way to judge the relative risks of two ETFs. If one ETF has a 3-year standard deviation of 12, you know that it is roughly twice as volatile as another ETF with a standard deviation of 6 and half as risky as an ETF with a standard deviation of 24. A real-world example: The standard deviation for most short-term bond funds falls somewhere around 0.7. The standard deviation for most precious-metals funds is somewhere around 26.0.

Important caveat: Don’t assume that combining one ETF with a standard deviation of 10 with another that has a standard deviation of 20 will give you a portfolio with an average standard deviation of 15. It doesn’t work that way at all, as you will see when I introduce Modern Portfolio Theory, later in this chapter. The combined standard deviation will not be any greater than 15, but it could (if you do your homework and put together two of the right ETFs) be much less.

Beta: Assessing price swings in relation to the market

Unlike standard deviation, which gives you a stand-alone picture of volatility, beta is a relative measure. It is used to measure the volatility of something in relation to something else. Most commonly that “something else” is the S&P 500. Very simply, beta tells you that if the S&P rises or falls by x percent, then your investment, whatever that investment is, will likely rise or fall by y percent.

The S&P is considered your baseline, and it is assigned a beta of 1. So if you know that Humongous Software Corporation has a beta of 2, and the S&P shoots up 10 percent, Jimmy the Greek (if he were still with us) would bet that shares of Humongous are going to rise 20 percent. If you know that the Sedate Utility Company has a beta of 0.5, and the S&P shoots up 10 percent, Jimmy would bet that shares of Sedate are going to rise by 5 percent. Conversely, shares of Humongous would likely fall four times harder than shares of Sedate in response to a fall in the S&P.

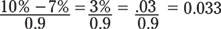

The Sharpe, Treynor, and Sortino ratios: Measures of what you get for your risk

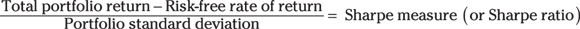

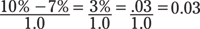

The risk-free rate of return generally refers to the return you could get on a short-term U.S. Treasury bill. If you subtract that from the total portfolio return, it tells you how much your portfolio earned above the rate you could have achieved without risking your principal. You take that number and divide it by the standard deviation (discussed earlier in this section). And what that result gives you is the Sharpe ratio, which essentially indicates how much money has been made in relation to how much risk was taken to make that money.

Suppose Portfolio A, under manager Bubba Bucks, returned 7 percent last year, and during that year Treasury bills were paying 5 percent. Portfolio A also had a standard deviation of 8 percent. Okay, applying the formula,

That result wasn’t good enough for Bubba Buck’s manager, so the manager fired Bubba and hired Donny Dollar. Donny, who just read Exchange-Traded Funds For Dummies, 3rd Edition, takes the portfolio and dumps all its high-cost active mutual funds. In their place, Donny buys ETFs. In his first year managing the portfolio, he achieves a total return of 10 percent with a standard deviation of 7.5. But the interest rate on Treasury bills has gone up to 7 percent. Applying the formula,

The higher the Sharpe measure, the better. Donny Dollar did his job much better than Bubba Bucks.

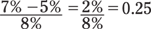

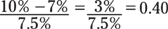

Suppose that Donny Dollar’s portfolio, with its 10 percent return, had a beta of 0.9. In that case, the Treynor measure would be

Is 0.033 good? That depends. It’s a relative number. Suppose that the market, as measured by the S&P 500, also returned 10 percent that same year. It may seem like Donny isn’t a very good manager. But when you apply the Treynor measure (recalling that the beta for the market is always 1.0),

you get a lower number. That result indicates that while Donny earned a return that was similar to the market’s, he took on less risk. Put another way, he achieved greater returns per unit of risk. Donny’s boss will likely keep him.

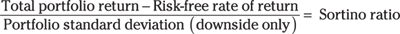

Another variation on the Sharpe ratio is the Sortino ratio, which basically uses the same formula:

Note that instead of looking at historical ups and downs, it focuses only on the downs. After all, say members of the Sortino-ratio fan club, you don’t lose sleep fretting about your portfolio rising in value. You want to know what your downside risk is. The Sortino-ratio fan club has been growing in size, but as yet, it is difficult to find Sortino-ratio calculations for any given security, including ETFs. I’m sure it will get easier over time, as comparing downside risk among various ETFs can be a helpful tool.

Meet Modern Portfolio Theory

For simplicity’s sake, I’ve discussed the choice of one ETF over another (SHY or SPY?) based on risk and potential return. In the real world, however, few people, if any, come to me or to any financial planner asking for a recommendation on a single ETF. More commonly, I’m asked to help build a portfolio of ETFs. And when looking at an entire portfolio, the riskiness of each individual ETF, although important, takes a back seat to the riskiness of the entire portfolio.

In other words, I would rarely recommend or rule out any specific ETF because it is too volatile. How well any specific ETF fits into a portfolio — and to what degree it affects the risk of a portfolio — depends on what else is in the portfolio. What I’m alluding to here is something called Modern Portfolio Theory: the tool I use to help determine a proper ETF mix for my clients’ portfolios. You and I will use this tool throughout this book to help you determine a proper mix for your portfolio.

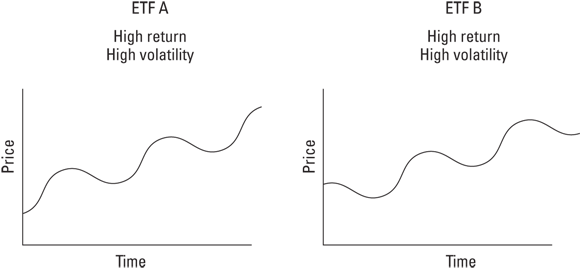

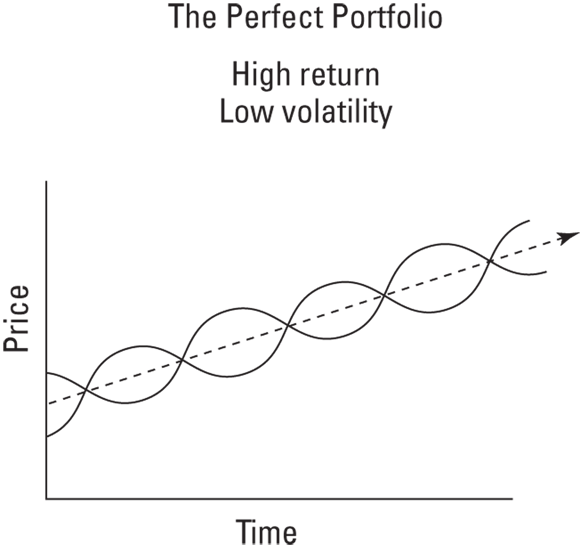

Tasting the extreme positivity of negative correlation

Modern Portfolio Theory is to investing what the discovery of gravity was to physics. Almost. What the theory says is that the volatility/risk of a portfolio may differ dramatically from the volatility/risk of the portfolio’s components. In other words, you can have two assets with both high standard deviations and high potential returns, but when combined, they give you a portfolio with modest standard deviation but the same high potential return. Modern Portfolio Theory says that you can have a slew of risky ingredients, but if you throw them together into a big bowl, the entire soup may actually splash around very little.

Figure 4-2 represents hypothetical ETF A and hypothetical ETF B, each of which has high return and high volatility. Notice that even though both are volatile assets, they move up and down at different times. This fact is crucial because combining them can give you a nonvolatile portfolio.

FIGURE 4-2: ETFs A and B each have high return and high volatility.

Figure 4-3 shows what happens when you invest in both ETF A and ETF B. You end up with the perfect ETF portfolio — one made up of two ETFs with perfect negative correlation. If only such a portfolio existed in the real world! (Note: I’m ignoring for the moment the so-called inverse ETFs, which promise negative correlation, but don’t always deliver. Chapter 18 covers those.)

FIGURE 4-3: The perfect ETF portfolio, with high return and no volatility.

Settling for limited correlation

When the U.S. stock market takes a punch, which happens on average every three years or so, most U.S. stocks fall. When the market flies, most stocks fly. Not many investments regularly move in opposite directions. I do, however, find investments that tend to move independently of each other much of the time, or at least they don’t move in the same direction all the time. In investment-speak, I’m talking about investments that have limited or low correlation.

Different kinds of stocks — large, small, value, and growth — tend to have limited correlation. U.S. stocks and foreign stocks — especially small-cap foreign stocks — tend to have even less correlation; see the sidebar, “Investing around the world.” But the lowest correlation around is between stocks and bonds, which historically have had almost no correlation.

Say, for example, you had a basket of large U.S. stocks in 1929, at the onset of the Great Depression. You would have seen your portfolio lose nearly a quarter of its value every year for the next four years. Ouch! If, however, you were holding high-quality, long-term bonds during that same period, at least that side of your portfolio would have grown by a respectable 5 percent a year. A portfolio of long-term bonds held throughout the growling bear market in stocks of 2000 through 2003 would have returned a hale and hearty 13 percent a year. (That’s an unusually high return for bonds, but at the time the stars were in perfect alignment.)

During the market spiral of 2008, there was an unprecedented chorus-line effect in which nearly all stocks — value, growth, large, small, U.S., and foreign — moved in the same direction: down…depressingly down. At the same time, all but the highest-quality bonds took a beating as well. But once again, portfolio protection came in the form of long-term U.S. government bonds, which rose by about 26 percent in value.

In August 2011, as S&P downgraded U.S. Treasuries, the stock markets again took a tumble, and — guess what? — Treasuries, despite their downgrade by S&P (but none of the other raters), spiked upward!

Reaching for the elusive Efficient Frontier

Correlation is a measurable thing, represented in the world of investments by something called the correlation coefficient. This number indicates the degree to which two investments move in the same or different directions. A correlation coefficient can range from –1 to 1.

A correlation coefficient of zero means that the two investments have no relationship to each other. When one moves, the other may move in the same direction, the opposite direction, or not at all.

As a whole, stocks and bonds (not junk bonds, but high-quality bonds) tend to have little to negative correlation. Finding the perfect mix of stocks and bonds, as well as other investments with low correlation, is known among financial pros as looking for the Efficient Frontier. The Frontier represents the mix of investments that offers the greatest promise of return for the least amount of risk.

Fortunately, ETFs allow you to tinker easily with your investments so you can find just that sweet spot.

Accusations that MPT is dead are greatly exaggerated

Since the market swoon of 2008, some pundits have claimed that Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) is dead. This claim is nonsense. As I mentioned, U.S. government bonds more than held their own during this difficult period. And even though all styles of stock moved down in 2008, they moved at different paces. And the degree to which they recovered has differed significantly. The same thing happened again in 2020 with the COVID-19 dip. You’ll see these differences in the charts in the upcoming sections, “Filling in your style box” and “Buying by industry sector.”

The investors who were hurt terribly in 2008 were those who sold their depressed stocks and moved everything into cash or “safe” bonds. Those bonds, at least long-term government bonds, then lost about 16 percent of their value in 2009. Those who flipped from stocks to bonds would have been doubly wounded. But those who kept the faith in MPT and rebalanced their portfolios, as I discuss fully in Chapter 23, would not have been so badly wounded. These investors would have been buying stock in 2008 instead of selling it. And any investor with a fairly well-balanced portfolio of stocks and bonds would have recouped their losses within two years after the market bottomed in March 2009. In 2020, buyers and holders saw their losses reverse even more quickly…a sign, I believe, of things to come. I do more crystal-ball gazing in Chapter 28.

Mixing and Matching Your Stock ETFs

Reaching for the elusive Efficient Frontier means holding both stocks and bonds — domestic and international — in your portfolio. That part is fairly straightforward and not likely to stir much controversy (although, for sure, experts differ on what they consider optimal percentages). But experts definitely don’t agree on how best to diversify the domestic-stock portion of a portfolio. Two competing methods predominate:

- One method calls for the division of a stock portfolio into domestic and foreign, and then into different styles: large cap, small cap, mid cap, value, and growth.

- The other method calls for allocating percentages of a portfolio to various industry sectors: healthcare, utilities, energy, financials, and so on.

My personal preference for the small to mid-sized investor, especially the ETF investor, is to go primarily with the styles. But there’s nothing wrong with dividing a portfolio by industry sector. And for those of you with good-sized portfolios, a mixture of both, without going crazy, may be optimal.

Filling in your style box

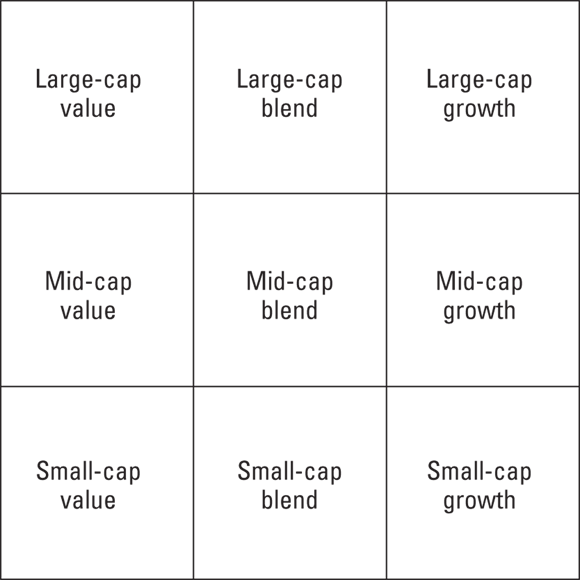

Most savvy investors make certain to have some equity in each of the nine boxes of the grid in Figure 4-4, which is known as the style box or grid (sometimes called the Morningstar Style Box).

FIGURE 4-4: The style box or grid.

The reason for the style box is simple enough: History shows that companies of differing cap (capitalization) size (in other words, large companies and small companies), and value and growth companies, tend to rise and fall under different economic conditions. I define cap size, value, and growth in Chapter 5, and I devote the next several chapters to showing the differences among styles, how to choose ETFs to match each one, and how to weight those ETFs for the highest potential return with the lowest possible risk.

Table 4-2 shows how well various investment styles, as measured by four Vanguard index ETFs that track each style, have fared in the past several years. Note that a number of ETFs are available to match each style.

TABLE 4-2 Recent Performance of Various Investment Styles

2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Large-Cap Growth | 6.17 | 27.75 | –3.32 | 37.26 | 40.27 |

Large-Cap Value | 16.95 | 17.14 | –5.45 | 25.83 | 2.29 |

Small-Cap Growth | 10.79 | 21.93 | –5.78 | 32.86 | 35.4 |

Small-Cap Value | 24.8 | 11.84 | –12.28 | 22.77 | 5.91 |

Buying by industry sector

The advent of ETFs has largely brought forth the use of sector investing as an alternative to the grid. Examining the two models toe-to-toe yields some interesting comparisons — and much food for thought.

One study on industry-sector investing, by Chicago-based Ibbotson Associates, came to the very favorable conclusion that sector investing is a potentially superior diversifier to grid investing because times have changed since the 1960s when style investing first became popular. As Ibbotson concluded,

Globalization has led to a rise in correlation between domestic and international stocks; large-, mid-, and small-cap stocks have high correlation to each other. A company’s performance is tied more to its industry than to the country where it’s based, or the size of its market cap.

The jury is still out, but I give an overview of the controversy in Chapter 10. For now, I invite you to do a little comparison of your own by looking at Tables 4-2 and 4-3. Note that by using either method of diversification, some of your investments should smell like roses in years when others stink. Also, recall what I stated earlier about how all stocks crashed in 2008 but recovered at significantly different paces; this is true of various styles and sectors. And it is certainly true for various geographic regions. Modern Portfolio Theory is not dead!

Table 4-3 shows how well various industry sectors (as measured by the returns of Vanguard indexed ETFs that match the index of each of the respective sectors) fared in recent years. Yes, there are ETFs that track each of these industry sectors — and many more.

TABLE 4-3 Recent Performance of Various Market Sectors

2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Healthcare | –3.32 | 23.35 | 5.49 | 22.0 | 18.34 |

Real Estate | 8.53 | 4.90 | –5.97 | 28.89 | -4.64 |

Information Technology | 13.75 | 37.04 | 2.43 | 48.75 | 46.09 |

Energy | 28.93 | –2.35 | –20.01 | 9.37 | -33.03 |

Don’t slice and dice your portfolio to death

One reason I tend to prefer the traditional style grid to industry-sector investing, at least for the nonwealthy investor, is that there are simply fewer styles to contend with. You can build yourself, at least on the domestic side of your stock holdings, a pretty well-diversified portfolio with but four ETFs: one small value, one small growth, one large value, and one large growth. With industry-sector investing, you would need a dozen or so ETFs to have a well-balanced portfolio, and that may be too many.

I hold a similar philosophy when it comes to global investing. Yes, you can, thanks largely to the iShares lineup of ETFs, invest in about 50 individual countries. (And in many of these countries, you can furthermore choose between large-cap and small-cap stocks, and in some cases, value and growth.) Too much! I prefer to see most investors go with larger geographic regions: U.S., developed markets, emerging markets…

You don’t want to chop up your portfolio into too many holdings, or the transaction costs (even if trading ETFs commission-free, there are still small, frictional costs when you trade) can start to bite into your returns. Rebalancing gets to be a headache. Tax filing can become a nightmare. And, as many investors learned in 2008 — okay, I’ll admit it, as I learned in 2008 — having a very small position in your portfolio, say, less than 2 percent of your assets, in any one kind of investment isn’t going to have much effect on your overall returns anyway.

Is risk to be avoided at all costs? Well, no. Not at all. Risk is to be mitigated, for sure, but risk within reason can actually be a good thing. That is because risk and return, much like Romeo and Juliet or Coronas and lime, go hand in hand. Volatility means that an investment can go way down or way up. You hope it goes way up. Without some volatility, you resign yourself to a portfolio that isn’t poised for any great growth. And in the process, you open yourself up to another kind of risk: the risk that your money will slowly be eaten away by inflation.

Is risk to be avoided at all costs? Well, no. Not at all. Risk is to be mitigated, for sure, but risk within reason can actually be a good thing. That is because risk and return, much like Romeo and Juliet or Coronas and lime, go hand in hand. Volatility means that an investment can go way down or way up. You hope it goes way up. Without some volatility, you resign yourself to a portfolio that isn’t poised for any great growth. And in the process, you open yourself up to another kind of risk: the risk that your money will slowly be eaten away by inflation. If you are ever offered the opportunity to partake in any investment scheme that promises you oodles and oodles of money with “absolutely no risk,” run! You are in the presence of a con artist or a fool. Such investments do not exist.

If you are ever offered the opportunity to partake in any investment scheme that promises you oodles and oodles of money with “absolutely no risk,” run! You are in the presence of a con artist or a fool. Such investments do not exist. Back in 1966, a goateed Stanford professor named Bill Sharpe developed a formula that has since become as common in investment-speak as RBIs are in baseball-speak. The formula looks like this:

Back in 1966, a goateed Stanford professor named Bill Sharpe developed a formula that has since become as common in investment-speak as RBIs are in baseball-speak. The formula looks like this:  As a rough rule, if you have $50,000 to invest, consider something in the ballpark of a 5- to 10-ETF portfolio, and if you have $250,000 or more, perhaps look at a 15- to 25-ETF portfolio. Many more ETFs than this won’t enhance the benefits of diversification but will entail additional trading costs every time you rebalance your holdings. (See my sample ETF portfolios for all sizes of nest eggs in

As a rough rule, if you have $50,000 to invest, consider something in the ballpark of a 5- to 10-ETF portfolio, and if you have $250,000 or more, perhaps look at a 15- to 25-ETF portfolio. Many more ETFs than this won’t enhance the benefits of diversification but will entail additional trading costs every time you rebalance your holdings. (See my sample ETF portfolios for all sizes of nest eggs in