Chapter 9

Going Global: ETFs without Borders

IN THIS CHAPTER

![]() Understanding how global diversification lowers risk

Understanding how global diversification lowers risk

![]() Calculating how much of your ETF portfolio to allocate overseas

Calculating how much of your ETF portfolio to allocate overseas

![]() Deciding upon your investment destinations

Deciding upon your investment destinations

![]() Choosing your best ETF options

Choosing your best ETF options

![]() Knowing what to avoid and when to stay home

Knowing what to avoid and when to stay home

If you were standing on a ship in the middle of the ocean (doesn’t matter whether it’s the Atlantic or Pacific), and you looked up and squinted real hard, you might see investment dollars sailing overhead. In the past 20 years, Americans have invested many billions overseas, and many ‘oversea-ers’ (the best part of being an author is getting to make up words) have invested in the United States. According to figures from the Investment Company Institute, the average U.S. investor in 2001 had but 13 percent of their equity portfolio allocated to non-U.S. stocks; today, that figure is 24 percent.

Many investors, alas, began to up their exposure to foreign stocks for the same reason that they move, moth-into-light style, into any other kind of investment: They were lured by high returns, especially the returns of emerging-market nation stocks, in the first decade of the new millennium.

As of mid-2011, the 10-year annualized return of the U.S. stock market stood at about 4 percent. In sharp contrast, stocks of the world’s emerging-market nations clocked in with a rather astounding 16 percent per year for the previous decade. Developed nations in the Pacific Rim (Japan, Australia, Singapore) more or less matched the United States for the decade. European stocks (including the United Kingdom), despite some sharp losses due largely to a debt mess in Greece and Portugal, showed an average return of about 6 percent.

Americans couldn’t get enough foreign stock, and their equity portfolios got up to about 30 percent foreign.

But, as is nearly always the case, once all the money poured into this hot sector, the sector cooled. Since 2011, the U.S. stock market has way outperformed foreign markets. In the past decade — mid-2011 to mid-2021 — the U.S. stock market has seen annual growth of nearly 14 percent, whereas developed overseas markets have grown only about 6 percent, and emerging-market nations have grown just a bit more than 3 percent.

Sure enough, American investors’ love affair with foreign stocks has started to wane. And the percent of Americans’ portfolios devoted to non-U.S. stock has shrunk again.

I’m going to suggest that you take careful note that U.S. investments sometimes do better than foreign investments, and sometimes not, and no one can say what the next decade will bring. Regardless, you do want to have your portfolio both at home and away. Not to chase returns — there really is no good reason to think that in the very long run, U.S. stocks will outperform foreign stocks, or the other way around — but to diversify your portfolio and smooth out your returns over time.

Fortunately, global diversification is easy with ETFs. In this chapter, I explain the whys and the hows of investing abroad.

The Ups and Downs of Different Markets around the World

For what it is worth, I do think you can expect that foreign stocks overall may do better than U.S. stocks in the coming decade. (If you want the nitty-gritty of my reasoning, you’ll find it later in this chapter.) But I certainly wouldn’t bet the farm on international stocks outperforming U.S. stocks — or underperforming them either, for that matter. If there is one thing I know for sure, it is that markets are unpredictable.

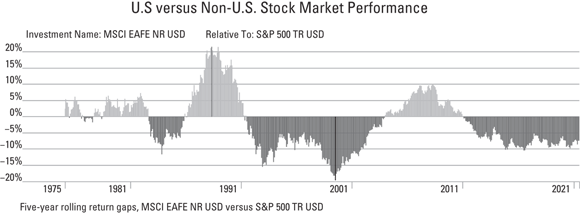

In all likelihood, international stocks as a whole will have their day. U.S. stocks will then come up from behind. Then international stocks will have their day again. And then U.S. stocks will get the jump. This type of horse race has been going on since, oh, long before Mr. Ed was on the air. Take a look at Figure 9-1. Note (as depicted by the peaks and valleys in the chart) that over a 45.5-year period, outperformance by U.S. stocks versus non-U.S. stocks has been followed quite regularly by years of underperformance.

© 2021 Morningstar, In. All Rights Reserved. Reproduced with permission.

FIGURE 9-1: U.S. versus non-U.S. stock-market performance, 1975–2021.

Note that the green “mountains” represent years that foreign stocks outperformed U.S. stocks, and the pink “valleys” represent years that foreign stocks underperformed U.S. stocks. (Foreign stocks and U.S. stocks are being measured by the popular indexes, the MSCI EAFE USD and the S&P 500 USD.) What will next year bring? No one can say.

Oh, by the way, the terms foreign and international are used interchangeably to refer to stocks of companies outside of the United States. The word global refers to stocks of companies based anywhere in the world, including the United States.

Low correlation is the name of the game

Why, you may ask, do you need European and Japanese stocks when you already have all the lovely diversification discussed in previous chapters: large, small, value, and growth stocks, and a good mix of industries? (See Chapter 5 if you need a reminder of what these terms mean.) The answer, mon ami, mi amigo, 我朋友, is quite simple: You get better diversification when you diversify across borders.

I’ll use several iShares ETFs to illustrate my point. Suppose you have a wad of money invested in the iShares S&P 500 Growth Index fund (IVW), and you want to diversify:

- If you combine IVW with its large value counterpart, the iShares S&P 500 Value Index Fund (IVE), you find that your two investments have a three-year correlation of 0.87. In other words, over the past three years, the funds have had a tendency to move in the same direction 87 percent of the time. Only 13 percent of the time have they tended to move in opposite directions.

- If you mix IVW into the same portfolio with the iShares S&P Small Cap 600 Growth Index Fund (IJT), you find that your two investments have tended to move up and down together by the same degree as IVW and IVE — 87 percent of the time.

- If you combine IVW with the iShares S&P Small Cap 600 Value Index Fund (IJS), your investments tend to move north or south at the same time 80 percent of time. Not bad. But not great.

Now consider adding some Japanese stock to your original portfolio of large growth stocks. The iShares MSCI Japan Index Fund (EWJ) has tended to move in synch with large U.S. growth stocks only about 76 percent of the time. And the ETF that tracks the FTSE China 25 Index (FXI) has moved in the same direction as large-cap U.S. growth stocks only 65 percent of the time. There’s clearly more zig and zag when you cross oceans to invest, and that’s what makes international investing a must for a well-balanced portfolio.

The increasing interdependence of the world’s markets wrought by globalization may cause these correlation numbers to rise over time. Indeed, investors saw in 2008 that in a global financial crisis, and again in 2020 with a global health crisis, stock markets around the world will suffer. The trend toward rising correlations has led some pundits to make the claim that diversification is dead. Sorry, those pundits are wrong. In down times, yes, stocks of different colors, here and abroad, tend to turn a depressing shade of gray together. When investors are nervous in New York, they are often nervous in Berlin. And Sydney. And Cape Town. That’s been true for years. The great apple-cart-turnovers of 2008 and 2020 were particular cases in point. But in both cases, it still paid to be diversified, as U.S. and foreign stocks recovered at very different rates.

Remember what happened to Japan

To just “stay home” on the stock side of your portfolio would be to exhibit the very same conceit seen among Japanese investors in 1990. If you recall, that’s when the dynamic and seemingly all-powerful rising sun slipped and then sank. Japanese investors, holding domestically stuffed portfolios, bid sayonara to two-thirds of their wealth, which, more than two decades later, they had yet to fully recapture. By year-end 2010, a basket of large-company Japanese stocks purchased in 1989 would have returned a very sad –1.3 percent a year over two full decades. In the following decade (2011–2021), Japanese stocks inched forward.

If you had bought the iShares MSCI Japan ETF at its inception in March 1996, your average annual return as of mid-2021 would have been a very disappointing 1.7 percent.

Ouch. It could also happen here. Or worse.

Finding Your Best Mix of Domestic and International

Why putting three-quarters of your portfolio in foreign stocks is too much

I see five distinct reasons to avoid overloading your portfolio with foreign stocks.

Currency volatility: When you invest abroad, you are usually investing in stocks that are denominated in other currencies. Because your foreign ETFs are denominated in euros, yen, or pounds, they tend to be more volatile than the markets they represent. In other words, if European stock markets fall and the dollar rises (vis-à-vis the euro) on the same day, your European ETF will fall doubly hard. If, however, the dollar falls on a day when the sun is shining on European stocks, your European ETF will soar.

Currency volatility: When you invest abroad, you are usually investing in stocks that are denominated in other currencies. Because your foreign ETFs are denominated in euros, yen, or pounds, they tend to be more volatile than the markets they represent. In other words, if European stock markets fall and the dollar rises (vis-à-vis the euro) on the same day, your European ETF will fall doubly hard. If, however, the dollar falls on a day when the sun is shining on European stocks, your European ETF will soar.Over the long run, individual currencies tend to go up and down. Although it could happen, it is unlikely that the dollar (or euro) would permanently rise or fall to such a degree that it would seriously affect your nest egg. In the short term, however, such currency fluctuations can be a bit nauseating. See more on currencies in the sidebar, “Pure (and purely silly) currency plays.” Note: There are currency hedged stock ETFs that can mitigate currency risk, but hedging adds to a fund’s expenses.

- Inflation issues: Another risk with going whole hog for foreign stock ETFs is that to a certain extent, your fortunes are tied to those of your home economy. Stocks tend to do best in a heated economy. But in a heated economy, you also tend to see inflation. Because of that correlation between general price inflation and stock inflation, stock investors are generally able to stay ahead of the inflation game. If you were to invest all your money in, say, England, and should the economy here take off while the economy there sits idly on the launch pad, you could potentially be rocketed into a Dickensian kind of poverty.

- Higher fees for foreign ETFs: There was once a huge difference in costs between foreign and domestic stock funds. This is far less true today. Still, domestic stock funds tend to cost a wee bit less than foreign. The Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI), for example, comes with an expense ratio of 0.03 percent. The iShares Core S&P Total U.S. Stock Market ETF (ITOT) has the same low, low cost ratio as Vanguard’s ETF. Schwab’s U.S. Broad Market ETF (SCHB) — yet again the same. All can be had for a measly 0.03 percent. Compare this to the Vanguard Total International Stock ETF (VXUS) and iShares’ and Schwab’s similar all-international ETFs (IXUS and SCHF): 0.08 percent, 0.09 percent, and 0.06 percent, respectively.

- Lower correlation with homegrown options: Certain kinds of stock funds in the United States offer similar low correlation to the rest of the U.S. market as do international stock funds, and I suggest leaving room in your portfolio for some of those funds. I discuss some of these industry-sector funds in Chapter 10. You may also want to make room for market-neutral funds, which I discuss in Chapter 25. And, of course, you want to leave plenty of room for the king of stock diversifiers: bonds (see Part 3).

- A double tax hit: Foreign governments almost always hit you up for taxes on any dividends paid by stocks of companies in their countries. You don’t pay this tax directly, but it is taken from your fund holdings. If your funds are held in certain accounts, Uncle Sam may want your money, too, and you wind up taking a double tax hit. This is a relatively minor reason not to go overboard when sailing overseas. (Specifics on this tax, and how to avoid getting double-whammied, are at the very end of this chapter.)

Why putting one-quarter of your portfolio in foreign stocks is insufficient

Some well-publicized research indicates that an 80-percent-or-so domestic stock/20-percent-or-so foreign stock portfolio is optimal for maximizing return and minimizing risk. But almost all that research defines domestic stock as the S&P 500 and foreign stock as the MSCI EAFE. The MSCI EAFE is an index of mostly large companies in the developed world. (MSCI stands for Morgan Stanley Capital International, and EAFE stands for Europe, Australasia, and Far East.) This analysis takes little account of the fact that you are not limiting yourself to the S&P 500 or to the MSCI EAFE. In the real world, you have the option of adding many asset classes to your portfolio of U.S. stocks. And among your international holdings, you can include developed-world stocks in Europe, Australia, and Japan; emerging-market stocks in China, India, and elsewhere; and foreign stocks in any and all flavors of large, small, value, and growth.

I wouldn’t want that. Neither would most investment professionals. So most err on the side of caution and give you a portfolio that’s more S&P 500 and less foreign — for their own protection, and not in the pursuit of your best interests.

With that said, I’ve seen some huge players in the investment world, such as Vanguard, slowly raise the allocation of foreign stocks in their recommended portfolios, about doubling it over the past 20 years. If you buy shares today of the all-in-one Vanguard Institutional Target Retirement 2040 Fund, 40 percent of your stock allocation will be non-U.S.

Why ETFs are a great tool for international investing

By mixing and matching your domestic stock funds with 40 to 50 percent international, you will find your investment sweet spot. In Chapter 21, I pull together sample portfolios that use this methodology. Time and time again, I’ve run the numbers through the most sophisticated professional portfolio analysis software available, and time and time again, 40-to-50-percent foreign is where I find the highest returns per unit of risk. And yes, this range has worked very well in the real world, too.

Although I try not to make forecasts because the markets are so incredibly unpredictable, I will say that if you had to err on the side of either U.S. or foreign stock investment, I would err on the side of too much foreign. The world economic and political climate is telling me that the U.S. stock market may be on relatively shakier ground. I could give you a long list of reasons that includes an aging population, the healthcare crisis, and the extent to which the United States is becoming a nation of haves and have-nots (historically great inequality leads to great dissension and upheaval), but the biggest reason is, as I alluded to earlier, valuations.

As of mid-2021, the U.S. stock market is expensive by almost any measure. Foreign markets are much less pricey. How strong a predictor are such valuations? One study by Vanguard found that about 40 percent of the stock market’s return in any given decade may be attributable to valuations at the start of the decade. So valuations are not foolproof as a predictor, but they are too good a predictor to be ignored. Note: Valuations have little to no predictive value in the shorter run. Anything can happen to stock prices over the next year, regardless of valuations.

As for me, I eat my own international cooking: I have fully half of my own stock portfolio in foreign stocks — the vast majority of it held in ETFs.

Not All Foreign Nations — or Stocks — Are Created Equal

At present, you have more than 300 global and international stock ETFs from which to choose. (Once again, global ETFs hold U.S. as well as international stocks; international or foreign ETFs hold purely non-U.S. stocks.) I’d like you to consider the following half dozen factors when deciding which ones to invest in:

What’s the correlation? Certain economies are more closely linked to the U.S. economy than others, and the behavior of their stock markets reflects that. Canada, for example, offers limited diversification. Western Europe offers a bit more. For the least amount of correlation among developed nations, you want Japan (the world’s second-largest stock market) or emerging-market nations like Russia, Brazil, India, and China.

What’s the correlation? Certain economies are more closely linked to the U.S. economy than others, and the behavior of their stock markets reflects that. Canada, for example, offers limited diversification. Western Europe offers a bit more. For the least amount of correlation among developed nations, you want Japan (the world’s second-largest stock market) or emerging-market nations like Russia, Brazil, India, and China.- How large is the home market? Although you can invest in individual countries, I generally wouldn’t recommend it. Oh, I suppose you could slice and dice your portfolio to include 50 or so ETFs that represent individual countries (from Belgium to Austria, and Singapore to Spain, and, more recently, Vietnam to Poland), but that is going to be an awfully hard portfolio to manage. So why do it? Choose large regions in which to invest. (The only exceptions might be Japan and the United Kingdom, which have such large stock markets that they each qualify, in my mind, as a region.)

- Think style. Consider giving your international holdings a value lean, and endeavor to get small-cap exposure as well as large, just as you do with your domestic holdings. You can also divvy up your foreign portfolio into industry groupings. I discuss this strategy in Chapter 10. I generally prefer style diversification to sector diversification, but using both together is warranted. You’ll note that I take the combined approach in my sample portfolios in Part 4 of this book.

- Consider your risk tolerance. Developed countries (United Kingdom, France, Japan) tend to have less volatile stock markets than do emerging-market nations (such as those of Latin America, the Middle East, China, Russia, or India). You want both types of investments in your portfolio, but if you are inclined to invest in one much more than the other, know what you’re getting into.

- What’s the bounce factor? As with any other kind of investment, you can pretty safely assume that risk and return will have a close relationship over many years. Emerging-market ETFs will likely be more volatile but, over the long run, more rewarding than ETFs that track the stock markets of developed nations. One caveat: Don’t assume that countries with fast-growing economies will necessarily be the most profitable investments; see the sidebar, “A boom economy doesn’t necessarily mean a robust stock market.”

Look to P/E ratios. How expensive is the stock compared to the earnings you’re buying? You may ask yourself this question when buying a company stock, and it’s just as valid a question when buying a nation’s or a region’s stocks. In general, a lower P/E ratio is more indicative of promising returns than is a high P/E ratio. (See Chapter 5 for a reminder of how to calculate a P/E ratio.) CAPE (also known as the Shiller P/E or PE 10 Ratio), stands for cyclically adjusted price-to-earnings-ratio, and looks at the P/E over 10 years, adjusted for inflation. Think of it as P/E 2.0. It has proven to be an even better (although far from fool-proof) indicator of future stock-market returns than P/E 1.0.

According to Bloomberg Indices, the current CAPE Ratio for the U.S. stock market is about 38, versus 23 for Europe, 24 for Japan, 19 for Korea, 17 for Spain, and 11 for Russia.

You want your portfolio to include U.S., European, Pacific, and emerging-market stocks, but if you are going to overweight any particular area, you may want to consider the relative P/E ratios, among other factors. Do keep in mind that certain countries, like Russia, have had lower multiples for a very long time, given political instability, lack of proper corporate governance, and so on. You might look at a country’s current ratios, not only as they compare to those of other nations, but also how they compare to that nation’s own historical averages.

Choosing the Best International ETFs for Your Portfolio

Although I’m (obviously) a huge fan of international investing and also a big fan of ETFs, I must admit that forming an optimal international portfolio is not the easiest thing in the world to do. For one thing, there’s too much to choose from! You clearly don’t want a portfolio of large growth, large value, small growth, and small value stocks in four separate ETFs (as I recommend for the U.S. holding) for every country in the world. That would make for one very cumbersome and unwieldly portfolio!

So you need to create a well-diversified, low-cost, tax-efficient foreign portfolio with some kind of lean toward value and small cap. How to do that?

Next, I suggest some of the ETFs you might consider first and foremost.

A number of brands to choose from

By and large, the ETFs I discuss here belong to a handful of ETF families: Vanguard, BlackRock (iShares), Schwab, Dimensional, and Cambria. Yes, there are other global and international ETFs from which to choose, and I discuss some of your other options in the next chapter, where I turn to global stocks divvied up by industry sector. As for global stocks that fit into a regional- or style-based portfolio, those mentioned in this section are among your best bets.

For more information on any of the international ETFs I discuss next, keep the following contact information handy:

- Vanguard:

www.vanguard.com; 1-800-662-7447 - BlackRock iShares:

www.ishares.com; 1-877-275-1225 - Schwab:

www.schwab.com; 1-800-435-4000 - Dimensional:

https://us.dimensional.com/individuals - Cambria:

www.cambriafunds.com; 1-855-383-4636

All the world’s your apple: ETFs that cover the planet

If you have a small portfolio and a strong desire to keep your investment management simple, you may be best off mixing and matching a total-market U.S. fund (see Chapter 5) with a total international fund. Be forewarned that a good number of ETFs that may seem “total international” are not. The Schwab International Equity ETF, for example, is a fine fund, but only if you want to limit your international exposure to developed nations. To get both developed and emerging-market stocks, you are better off with the Vanguard Total International Stock ETF (VXUS) or the iShares Core MSCI Total International Stock ETF (IXUS). Both of these funds give you instant exposure to everything in the world of stocks, minus U.S. investments. Both ETFs are ultra low-cost (0.08 for Vanguard; 0.09 for iShares), well diversified, and tax-efficient. The two funds are, in fact, VERY similar.

If you really want to keep things simple, you can buy a single ETF that tracks an index of all stocks everywhere, U.S. and foreign. That one fund would be either the Vanguard Total World Stock ETF (VT), with an expense ratio of 0.08 percent, or the SPDR Portfolio MSCI Global Stock Market ETF (SPGM), with an expense ratio of 0.09 percent. Both are perfectly fine options. These indexed ETFs, like practically all others, are self-adjusting. That is, if your goal is to own a single global fund that reflects each country’s percentage of the global economy, as that percentage grows or shrinks, so will its representation in these ETFs. Easy!

And if you really, really want simplicity — stocks and bonds and the kitchen sink, all in one package — see the end of Chapter 20 for suggestions.

If you have a portfolio larger than a few hundred dollars, and you’re paying nothing in commissions to trade, and you are okay with adjusting its alignment (via rebalancing) once a year or so, I suggest that you keep your stocks and bonds in separate funds and that you furthermore break down your stock holdings into U.S. and non-U.S. Then, just as I have advised for your domestic stocks, assign your foreign holdings to at least two categories, developed-nation and emerging-market stocks.

If you’ve read the preceding Part 2 chapters, you know that my preferred way to split your U.S. stock holdings is by style: large growth, large value, small growth, and small value. On the international side, you could do the same, but I don’t think you need to. Dividing both developing national and emerging markets into four categories each can be done, but it’s a bit cumbersome at rebalancing time to deal with so many funds. And, especially where emerging markets are concerned, small-cap and value options tend to be expensive.

Instead, I suggest a broad developed-markets fund, a broad emerging-markets fund, and two other foreign funds to give the portfolio a value lean and an extra heaping of small cap. Remember that most “total market” funds are market weighted, so you will be getting mostly large-cap exposure, which is why you’ll want to add some small cap as a separate dish.

Oh, you could also slice the overseas pie into regions: European, Pacific, and emerging markets. This option would be fine, although you’d be lacking in Canadian stocks. Or you could buy an international value, an international growth, and an international small-cap ETF. This would be fine, as well, although your expense ratio would be higher than with the strategy I’m recommending.

Let’s take a closer look at that strategy, and some of the ETFs you might employ.

Developed-market ETFs: From the North Sea to the Land of the Rising Sun

By developed markets, we investment people generally mean Western Europe, the Pacific Rim (Japan, Australia, New Zealand), and Canada — in other words, the richer countries of the world. Sometimes, depending on the indexer, you might also encounter South Korea, Taiwan, South Africa, and Israel.

Europe boasts the oldest, most established stock markets in the world: the Netherlands, 1611; Germany, 1685; and the United Kingdom, 1698. Relative to the stocks of most other nations, European stocks, as a whole, are seemingly low-priced (going by their P/E ratios, anyway).

Europe’s strengths include political stability (well, Brexit aside…), an educated workforce, and a confederation of national economies making for the world’s largest single market. Germany, the largest economy in Europe, has been growing its export industry faster than any other nation on the planet.

Europe’s great weaknesses include a persistently high rate of unemployment (outside of Germany); a rapidly aging population; and a few member nations, most notably Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain, whose governments have racked up some very serious debt. (Collectively, these high-debt nations have been referred to in investment circles as the PIGS, although the acronym may need to change because Belgium has recently surpassed Spain in terms of its debt-to-GDP ratio.)

Still, even with its weaknesses on full display, the European market definitely deserves a piece of your portfolio.

The stock markets of the Pacific Rim combined represent capitalization fairly close in size to Europe’s stock markets. With the rapid growth of China as the world’s apparent soon-to-be largest consumer, surrounding nations may bask in its economic glory. Australia, in particular, has benefited greatly from China’s thirst for natural resources. And Japan leads the world in labor productivity. Alas, Japan also leads the world in government debt, and over the entire region, the threat posed by North Korea, and the tensions between China and Taiwan, loom like black clouds.

But black clouds and all, the Pacific region, like the Eurozone, merits a chunk of any balanced portfolio.

Want to tap into the developed-nations market in one fell swoop? Consider the following ETFs.

SPDR Portfolio Developed World ex-US ETF (SPDW)

Indexed to: S&P Developed Ex-U.S. BMI Index. BMI stands for Broad Market Index. Broad? Enough. This fund has 2,320 holdings.

Expense ratio: 0.04 percent

Top five country holdings: Japan, United Kingdom, France, Canada, Germany

Russell’s review: With the lowest expense ratio in the category, heck yeah, I like it. The diversification isn’t quite that of Vanguard’s equivalent (the next one), but there is enough breadth that you needn’t worry about overconcentration. The single largest holding is Samsung Electronics, taking up just 1.59 percent of the portfolio.

Vanguard FTSE Developed Markets ETF (VEA)

Indexed to: FTSE Developed All Cap ex-US Index of 4,035 stocks

Expense ratio: 0.05 percent

Top five country holdings: Japan, United Kingdom, France, Canada, Germany

Russell’s review: As with all Vanguard funds, you get solid basics here at a very reasonable cost. And few funds are as well diversified as this one. The single largest holding is Nestlé S.A., with but 1.41 percent of the portfolio. Samsung Electronics is second, with 1.35 percent of the portfolio.

Dimensional Core Equity Market ETF (DFAI)

Indexed to: Dimensional’s own recipe, which qualifies this fund as “actively managed,” even though you likely won’t see more turnover with this fund than with a typical index fund. The expense ratio is also more like an index fund than an actively managed fund.

Expense ratio: 0.18 percent

Top five country holdings: Japan, United Kingdom, Canada, France, Germany

Russell’s review: Dimensional launched a handful of ETFs, including this one, in 2020. Dimensional has been in the mutual fund business for many years, and their claim to fame is that they incorporate a value lean and provide greater exposure to small cap than the establishment indexes. This makes beautiful sense. And if you go with this fund (despite the higher expense ratio), you may not need the value and small-cap ETFs I recommend later — provided you pair this fund with Dimensional’s Core Emerging Market ETF (DFAU). But know that DFAU has an expense ratio of 0.36 percent, significantly more than some other good emerging-market funds.

Emerging-market stock ETFs — Well, we hope that they’re emerging

When economists feel optimistic, they call them “emerging-market” nations. But these same countries are also sometimes referred to as the Third World or, even more to the point, “poor countries.” I’m talking about China, Taiwan, Mexico, Russia, India, Brazil, and South Africa, among others. In 2013, Greece, given a huge drop in average income, had the dubious honor of being the first developed nation to be downgraded to emerging-market status by a major indexer (MSCI).

All together, the emerging-market nations make up 6 billion people, or about 85 percent of the world’s population, but only about 41 percent of global GDP, and 13 percent of global equity market capitalization.

Much of the fortunes of emerging-market nations, especially those of sub-Saharan Africa and South America, are tied to commodity production. But commodity prices fluctuate greatly. And political unrest (often due to the fact that commodity production is controlled by very few), corruption, and overpopulation, as well as serious environmental challenges, plague many of these countries.

On the other hand, emerging-market stock prices — vis-à-vis U.S. stock prices, and even those of developed nations — seem underpriced at the moment. Many emerging economies seem especially strong. And — perhaps most importantly — these countries have young populations. Children tend to grow up to be workers, consumers, and perhaps even investors. Future growth of the economies seems almost assured. This should pan out to mean some profitability to shareholders in emerging-market stocks and ETFs.

Here are some excellent ETF options for capturing the performance of emerging markets.

Vanguard MSCI Emerging Market ETF (VWO)

Indexed to: The FTSE Emerging Markets All Cap China A Inclusion Index. You’re looking at 5,200 stocks.

Expense ratio: 0.10 percent

Top five country holdings: China, Taiwan, India, Brazil, South Africa

Russell’s review: A good way to capture the potential growth of emerging-market stocks is through VWO. The cost is the lowest in the pack, and the diversity of investments is more than adequate. My only problem is that China represents nearly 41 percent of the portfolio. That is in line with the market-weighting of Chinese-company stocks compared to the rest of the nations. Still, I wouldn’t mind at all if Vanguard were to limit any one country’s representation to, oh, maybe 30 percent of the total portfolio.

iShares Core MSCI Emerging Markets (IEMG)

Indexed to: MSCI Emerging Markets Investable Market Index. This features 2,515 holdings.

Expense ratio: 0.11 percent

Top five country holdings: China, Taiwan, South Korea, India, Brazil

Russell’s review: Good fund. Good company. Good index. In fact, because China makes up less than 35 percent of the total portfolio, versus Vanguard’s 41 percent, I might give the edge to this ETF, despite the slightly higher (very slightly higher) expense ratio, and more limited company diversification. But it would be a close call.

Dimensional Emerging Core Equity Market ETF (DFAE)

Indexed to: Dimensional’s own propriety index. They’ve thrown in 4,100 holdings, and they’ve given the portfolio a value and a small-cap lean.

Expense ratio: 0.35 percent

Top five country holdings: China, Taiwan, South Korea, India, Brazil

Russell’s review: It’s significantly more expensive than some other emerging-market options, but this fund does offer advantages. One is the value and small-cap lean, making this fund perhaps the best-in-class if you are only going to have one developed-market and one emerging-market ETF and not supplement them with separate international value and small-cap ETFs. In the very long run, those leans would give this fund a distinct advantage in terms of performance. Also, this fund gives Chinese stocks 34 percent of the total capitalization, which is high, but not as high as the other emerging-market ETFs.

Adding value to your international portfolio

Studies show that the same value premium — the tendency for value stocks to outperform growth stocks — that seemingly exists here in the United States can be found around the world. (See the full value premium discussion in Chapters 6 and 8.) Therefore, I suggest a mild tilt toward value in your international stock portfolio, just as I recommend for your domestic portfolio.

Or, if you’ve already decided to split your international stocks by regions — Europe, Pacific, emerging markets — then adding a bit of IVLU can give you the value lean you seek.

iShares MSCI International Value Factor ETF (IVLU)

Indexed to: MSCI World ex USA Enhanced Value Index

Expense ratio: 0.30 percent

Top five country holdings: Japan, United Kingdom, France, Germany, Switzerland

Russell’s review: There aren’t a lot of ETF offerings in international value, so I’m grateful this fund exists. The cost is reasonable. The index is good and value-y (that’s where the “enhanced” comes in). You’re only getting developed-world stocks, no emerging markets, but that’s okay as long as your total international exposure is balanced. If you want to add value on both the developed-market and emerging-market sides of your international portfolio, you’ll have to go for now with a mutual fund, rather than an ETF. Vanguard’s International Value Fund (VTRIX) is a good option. More on this, and other mutual funds to consider adding to your ETF portfolio, in Chapter 25.

Cambria Global Value ETF (GVAL)

Indexed to: This is not an index fund but an actively managed fund with a strategy that attempts to concentrate and thicken the value premium by selecting the most undervalued companies in those countries that themselves seem undervalued.

Expense ratio: 0.59 percent

Top five country holdings: Poland, Austria, Italy, Columbia, Greece

Russell’s review: I know, I know…I say I don’t like actively managed funds, and I don’t like high expense ratios, but this fund’s strategy is just too compelling to ignore. As I’m writing these words in mid-2021, this fund has returned 6.5 percent annually for the past five years. That’s not very good. But these past five years have been awfully crappy years for both international and value stocks. When international and value come back into vogue, this fund could really shine. If Cambria were to lower the expense ratio, I could get really enthusiastic.

Small-cap international: Yes, you want it

Small-cap international stocks have even less correlation to the U.S. stock market than larger foreign stocks. The reason is simple: If the U.S. economy takes a swan dive, it will seriously hurt conglomerates — Nestlé, Toyota, and Samsung Electronics, for example — that serve the U.S. market, regardless of where their corporate headquarters are located. A fall in the U.S. economy and U.S. stock market is less likely to affect smaller foreign corporations that sell mostly within their national borders. A mid-sized bank in Tokyo that makes its profits selling mortgages may be entirely immune to any goings-on on Wall Street.

Regardless of the investment vehicle you choose, I suggest that a good chunk of your international stock holdings — perhaps as much as 50 percent, if you can stomach the volatility — go to small-cap holdings. The two ETFs I’d like you to consider are from Vanguard and iShares. Note that there are considerable differences between the two.

Vanguard FTSE All-World ex-US Small Cap Index (VSS)

Indexed to: The FTSE All-World Small Cap Ex-US Index, which tracks more than 4,100 small-cap company stocks in both developed nations (77 percent of the stocks) and emerging markets (23 percent)

Expense ratio: 0.11 percent

Top five country holdings: Canada, Japan, United Kingdom, Taiwan, China

Russell’s review: For exposure to small-cap international stocks, you aren’t going to find a less expensive or more diversified fund.

iShares International Developed Small Cap Value Factor ETF (ISVL)

Indexed to: FTSE Developed ex US ex Korea Small Cap Focused Value Index

Expense ratio: 0.30 percent

Top five country holdings: Canada, Japan, United Kingdom, Sweden, Australia

Russell’s review: I’ve long lamented, and have been quite surprised, that it took the ETF industry until 2021 to provide investors with a small-cap, truly international (both developed-world and emerging-market) value fund. And finally, here it is! If you’ve taken my advice, and you build your international portfolio with one core developed-market fund and one core emerging-market fund, then adding ISVL can, in and of itself, give you the added exposure to both small cap and value that academic research says is likely to sharply increase your returns over the long haul. Downside: The expense ratio, while certainly reasonable, is higher than the Vanguard small-cap offering.

The reason to invest abroad isn’t primarily to try to outperform the Joneses…or the LeBlancs, or the Yamashitas. Rather, the purpose is to diversify your portfolio so as to capture overall stock-market gains while tempering risk. You reduce risk whenever you own two or more asset classes that move up and down at different times. Stocks of different geographic regions tend to do exactly that.

The reason to invest abroad isn’t primarily to try to outperform the Joneses…or the LeBlancs, or the Yamashitas. Rather, the purpose is to diversify your portfolio so as to capture overall stock-market gains while tempering risk. You reduce risk whenever you own two or more asset classes that move up and down at different times. Stocks of different geographic regions tend to do exactly that.