6

Scale: Assembling the Assets to Build a New Venture

A quick scan of Amazon's list of top books on innovation will yield an important insight: managers spend a lot more time thinking about how to generate new ideas than they do on how to make them successful. There is copious literature on customer insight, open innovation, and a myriad of other fabulous approaches to generating the spark of imaginative brilliance that gets innovation started. Lean startup has popularized business incubation. Business and engineering schools have put the practices of business experimentation and user-centered design at the heart of the curriculum. What gets much less attention is the third discipline of innovation, scaling. Scaling is turning a validated idea into a revenue-generating business.

By 2019, this had become Balaji Bondili's challenge. He had successfully incubated Pixel as a new way for Deloitte to solve complex client problems. Bondili and his team had nurtured the new venture, run experiments to validate its value to clients, and learned how to work alongside the existing Deloitte business. They knew that they had a viable business model that was getting real traction with clients and starting to generate fees. He now had to take the venture to the next level by scaling Pixel into a sustainable source of revenue. What should Bondili do? What is the playbook for a Corporate Explorer like Bondili in this situation? What is the equivalent of lean startup in incubation or design thinking for ideation?

A conventional answer is to buy scale by leveraging a firm's balance sheet to add assets to the fledgling unit so that it can bulk up quickly. It is a fast track to the future. The problem with it is that large acquisitions are difficult to integrate and smaller, early-stage ones, often have the same odds of success as a startup. The financial returns of venture funds show that the aggregate investments in startups are not particularly attractive. A report by Morgan Stanley concluded that the return on investment in venture capital funds in the twenty-first century is broadly in line with those of other major stock market indices, despite the far higher risks associated with funding startups.1 Larger acquisitions face even higher odds of failure. One study found that 60% of acquisitions destroy shareholder value.2 Another found that 83% of acquisitions failed to achieve their objectives.3 The academic consensus is that corporate acquisitions, on average, fail and the value of write-offs exceeds gains by a wide margin.4

A new venture needs to define its scale of ambition: what will be different in the world when we succeed? Krisztian Kurtisz wanted an insurance company that excited customers without needing a bureaucracy to manage claims processing. Balaji Bondili wanted to reinvent consulting, so that clients had access to the best skills, with more flexibility. A new venture team then works backwards from the vision to today, asking: what would it take for us to get there? These endpoints are not fixed – both Kurtisz and Bondili iterated their visions – they create an awareness of the decisions Corporate Explorers need to take to scale the business. IBM’s emerging businesses scaled by leveraging assets like products, sales channels, and back-office assets from the core business. They added to their offerings by making selected acquisitions and developing numerous ecosystem partnerships.5

We are not against making acquisitions – far from it – they are an important element of the Corporate Explorer's toolkit. However, the data show that acquisitions alone are an unreliable path to growth. Acquisitions need to be done with a clear sense of how they will complete an offering, and without that the odds are high that they will destroy, not enhance, value. Our recommendation is that Corporate Explorers have a plan for combining assets from different sources to take a new venture to scale. Acquire with a purpose, not as a shortcut to success.

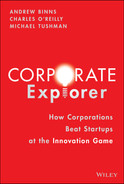

When Carol Kovac at IBM started the Life Sciences EBO, she had no idea where they would end up. She learned that setting a long-term ambition for the business was very helpful in enabling her to pivot the unit's strategy at key moments. Having a hypothesis about the destination makes it possible to have a roadmap and to do “route recalculation” as circumstances changed. Venture capitalists often ask an entrepreneur seeking funding, “What's the exit?” For example, a sale to another firm or public offering of the stock might be an exit. A Corporate Explorer should ask, “What’s the endpoint.?” Then, and think about the series of steps needed to get there. In this Chapter, we will describe how Corporate Explorers can implement this approach by combining assets. Corporate Explorers assemble three types of assets – customers, capabilities, and capacity. The strategy for combining assets is a scaling path. It describes the anticipated sources for the assets – acquisitions, new build, leverage from the core, partnerships, investments, platforms – together with an initial entry point. The scaling path is a map a Corporate Explorer can use to track the evolving options for how to piece together customers, capabilities, and capacity to realize their goal. It helps to make the Corporate Explorer aware of the opportunities that may exist to assemble the assets for scaling. It sensitizes them to key decision or trigger points, that they need to be aware of when it is time to invest in new assets (see Figure 6.1). In the final part of this chapter, we will illustrate this by returning to the story of Balaji Bondili and Deloitte Pixel. First, the story of Jim Peck illustrates how combining assets with purpose works.

Figure 6.1 Assets for scaling.

Combining Assets

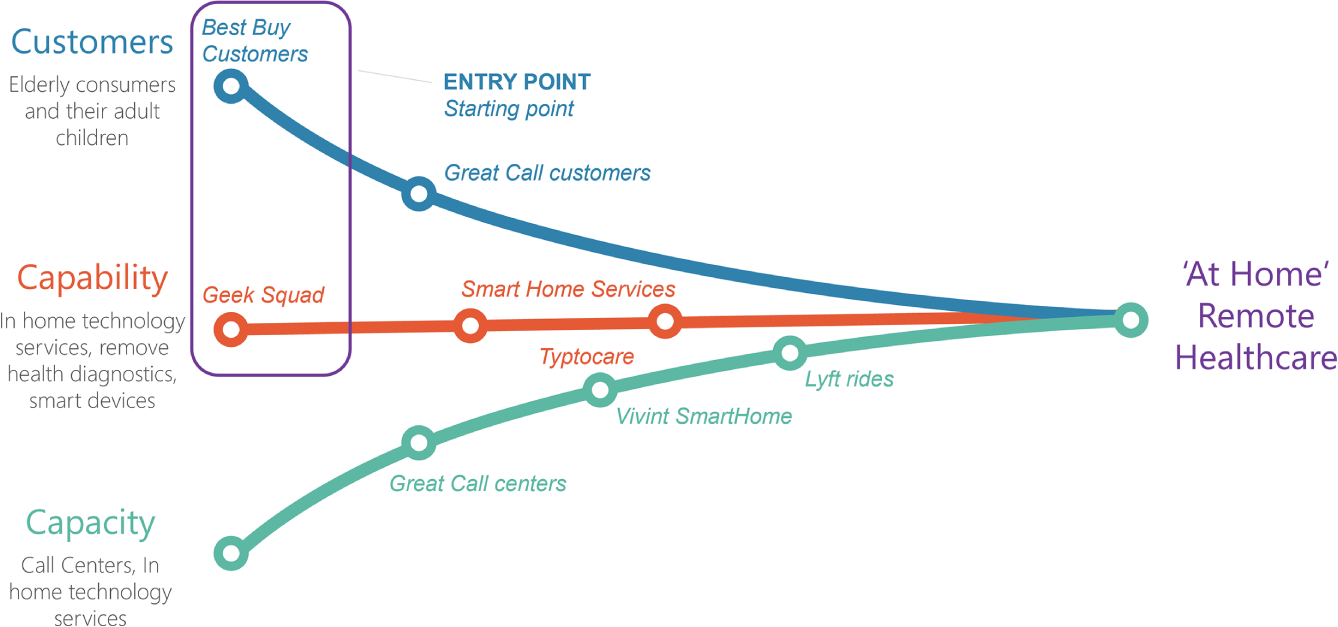

In the early 2000s, long before the term big data became popular, Jim Peck saw an opportunity to create one of the world's first big-data analytics companies. He had worked for a decade for LexisNexis (LN), an online legal information company, founded in the 1970s to provide online access to US case law and legal precedents via a dial-up modem. When it first launched, LexisNexis provided the ability to access public legal records electronically and was a revelation. Legend has it that the firm's private presentation to the US Supreme Court Justices, originally scheduled for 30 minutes, lasted nine hours – such was their interest in the new technology. LexisNexis’ service, which aggregated publicly available information about legal cases involving individuals and companies and made it easy to search and cross-reference, was rapidly adopted by the legal community.

Peck and team realized that these public records could be valuable to a much wider market. The company was already providing information to various government and commercial organizations, helping them to identify individuals. However, it would be even more valuable if public records about property ownership, bankruptcies, and criminal convictions were combined with nonpublic information like social security numbers and dates of birth. If LN could aggregate and make connections between these numerous, large data sets, they could enable rapid background checks or predictions about who would keep up with payments on a phone contract or bank loan, helping firms identify potential risks and frauds far more successfully. This would make it possible to differentiate between people with the same name and assess the risk of doing business with them. There was a strong demand for these sorts of data-based insights, and it was clear that offering this new capability could expand their market exponentially. It would transform LN from a data company into one of the first big data analytics companies.

LexisNexis already had some of the data assets to pull this off. They had a presence in markets like government agencies, a strong brand, and management capability. What they lacked was the technological capability to aggregate and link data across multiple sources and large enough data sets on individuals. These deficiencies would limit their market reach, locking them out of the lucrative insurance market. Technology capability and data capacity were clear gaps on its scaling path. If they could fill them, a new business would be born.

In 2004, LN acquired a small software company in Boca Raton, Florida, called Seisint. The CEO was technology guru Hank Asher. Working on contract with the US government, Asher had developed state-of-the-art data fusion software that linked disparate data sets and made them available very quickly through a flexible search interface. Integrating the Seisint technology within its existing platform consolidated LN's leadership in the public records business. More importantly, the technology – the high-performance computing cluster (HPCC) – gave LN the advanced data analytics capability it needed to disrupt other markets. With this technology in-hand, they then needed access to a large data set in an adjacent market. It is here that Peck's plan became truly disruptive. He proposed the largest acquisition in the company's history by acquiring ChoicePoint, a multibillion-dollar firm. ChoicePoint operated CLUE, a repository of all automotive insurance claims in the United States.

The plan was to integrate thousands of legacy databases from ChoicePoint onto the HPCC platform and link these with the existing public records data. The impact was a step-change improvement in an insurance agent's ability to spot high-risk applicants for car insurance. It made almost instant automobile insurance policy decisions possible, spurring a host of innovations from the insurance industry. More than 80% of automobile insurance transactions in the United States now use LN's “pre-fill” functionality, giving insurance firms most of the data they need before a consumer even starts an application. Consumers need only confirm the data, saving them time, adding massive efficiencies to the process, and reducing abandoned applications.

LexisNexis’ acquisitions of Seisint and ChoicePoint helped take a small unit focused on public records and scale it to a multibillion-dollar business. LexisNexis Risk Solutions is a pioneer in big data analytics created from the original legal information firm, but it now has revenues that far exceed its parent. It has added multiple other business lines since then as it seeks to leverage the computing platform to disrupt other industries and, as of 2018, the firm maintained more than 17 billion records of individuals and businesses, which it sold to more than 100,000 clients. LexisNexis Risk Solutions is far more than a mergers and acquisitions (M&A) fueled growth story. Jim Peck used acquisitions to realize a strategic ambition, combining the firm's own assets with those of the companies they bought.

Customers, Capabilities, Capacity

Jim Peck assembled the assets needed to scale his venture. He was agnostic about the source. What mattered was putting together the pieces that would enable him to achieve the goal of scaling the business. There are three types of assets that Peck and other Corporate Explorers need:

- Customers – access to channels, customer base, sales teams, and so on that provide the market reach needed to drive revenue. ChoicePoint's access to insurance companies and corporate background checks enhanced and expanded LN's existing customer base.

- Capabilities – the technologies, products, skills, and the business models needed to deliver on the value proposition. LexisNexis added the HPCC data engine to its existing platform and public records data. This technology was the fundamental building block for the business.

- Capacity – the ability to manage a business operating at increasing volumes, which could mean fulfillment, logistics, manufacturing, customer service, call centers, and so on. Bondili needs people with the right skills in Pixel's expert crowd (capability), but he also needs enough people to satisfy the needs of a growing organization (capacity). ChoicePoint added data on a massive scale, which made the HPCC technology capabilities more valuable.

There are different ways to meet these needs. Can the venture build it themselves; can it leverage the assets of the core business, can it acquire from outside the firm or partner with others to gain access to what they need? The major French insurance company, AXA, has made multiple plays to support its move into becoming a healthcare provider, using telemedicine and other remote-care technologies. AXA's goal is to be a first point of contact for its customers on primary healthcare. As one AXA executive describes it, we are “[…] in the process of integrating different building blocks of the care path so that we can manage it from A to Z in the service of the patient.” This is an ambitious goal in a country with a comprehensive public healthcare system. AXA started by building France's first teleconsultation service, BonjourDocteur, which allowed AXA's beneficiaries to make appointments to see virtual doctors, download prescriptions, find a local pharmacy, and manage their own medical profile. AXA then added capacity of more medical practitioners through a partnership with Qare, a virtual network of French general practitioners and specialists serving corporate subscribers, and expanded fivefold AXA's provider network of GPs and specialists. AXA had first invested in Qare and incubated it within its venture unit. This capacity expansion gave the company the ability to offer 24/7 access to a network of experienced, internationally qualified doctors in more than 20 languages and enabled the company to complete 80,000 consultations by the end of 2019. AXA is just getting started; it aims to expand beyond those 400 practitioners in 2019 to 15,000 by 2021. AXA also focused on expanding its capability through a partnership with H4D. H4D offers a self-contained medical kiosk called the Consult Station that enables patients to take their own vital signs, conduct self-checkups using video tutorials, and get medical teleconsultations via BonjourDocteur. This partnership extended AXA's customer reach to new rural populations in “medical deserts” – that is, towns that suffer from a lack of doctors.

AXA is deliberately building a position in the French healthcare ecosystem that will allow it to become a leader in technology-enabled patient services. It is not biased toward any specific scaling approach for doing this – building, buying, leveraging, partnering, and investing are all viable strategies toward its disruptive goal. Table 6.1 illustrates this approach. Although it is too early to say if AXA's move into healthcare will enable it to achieve its goals, the corporation overall continues to perform strongly, and the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a massive accelerant to remote medicine.

Table 6.1 AXA scaling strategies.

Each venture needs its own strategy for assembling customers, capabilities, and capacities. Although, there are some common themes behind what is hard or easy to leverage from the mothership, the existing customer base and brand are the most likely assets that an established firm can bring to the new venture. Bringing a new technology capability to an existing customer base is an excellent strategy for rapid scaling.

The 200-year-old Boston-based Eastern Bank acquired the founding team of a collapsed FinTech startup to create Eastern Labs to find a way to reinvent banking using data analytics. They leveraged the bank's core asset – its customer relationships – to develop and deploy a revolutionary algorithm for near-instant bank loan decisions. Brand is another customer-facing asset to leverage. In the next chapter, we will describe how Mark Kelsey took a stable of dying business magazines and made them into an online data business that can tap into the subscribers and advertisers by leveraging prestige magazine brands like The Bankers Almanac. This gave them market access that others would struggle to replicate.

Getting the capability to scale a digital business is a challenge for traditional firms. There is a digital talent gap with most firms unable to hire, and keep, the data science, AI, analytics, machine learning, and software skills that they need.6 This was the key acquisition that Eastern Bank made. Similarly, Jim Peck's acquisition of Seisint gave LexisNexis the fundamental edge that enabled it to build its Risk Analytics business. Instead of building his own team of insurance underwriters and applying for separate licensing with regulators for Cherrisk, Kriztian Kurtisz leveraged UNIQA's core business capability of insurance underwriting to move faster than would otherwise have been possible. Access to capacity to scale can mean manufacturing, supply chain, or customer service capabilities. These sorts of assets typically require major capital investment and time to build, so they are good candidates for leveraging from the core. For example, Kevin Carlin leverages Analog Devices’ manufacturing facilities to build the devices that are integral to his venture's condition-based monitoring solution.

Scaling Paths

Successfully scaling a new venture involves making good judgments about how to build these assets. Those judgments should not wait until the end of incubation. You need to plan much earlier, developing hypotheses for how to scale. We often say, “scaling starts in ideation.” That is when the Corporate Explorer maps a scaling path – a deliberate sequencing of steps from an incubated new venture to a fully operational revenue-generating business. The first step on the path is mapping out what assets you can leverage from the core business. Bondili starts on the road to develop Pixel because he knows Deloitte has access to clients willing to pay to solve difficult problems. Kurtisz knows when he starts work on Cherrisk that he can leverage UNIQA's existing insurance licenses. Then, the scaling path informs the experimentation plan, helping to teach the Corporate Explorer what else they might need. It is a way of finding some of the riskiest assumptions that you need to test – the places where you have the most to learn. The scaling path also helps to prepare senior leaders for what's coming. If there are potential large-scale investments or acquisitions down the road, the earlier the Corporate Explorer starts to warm up the CEO to this reality, the more likely it is that they will win support when it is needed.

In describing this approach to building a scaling path, we are committing the sin of retrospective coherence – using hindsight to discern a beautiful plan in the actions of others. Some Corporate Explorers did create scaling paths in advance – we worked with them to do that – most do the thinking without formalizing it. LexisNexis may not have had a detailed blueprint for every step, but it still consciously executed a series of steps on a path toward the larger ambition. When LN acquired Choicepoint, it had a plan from day one for what it wanted to do and wasted no time executing it. Peck charted a path backward from his ambition of being a big data disruptor and identified the key assets that he needed to assemble.

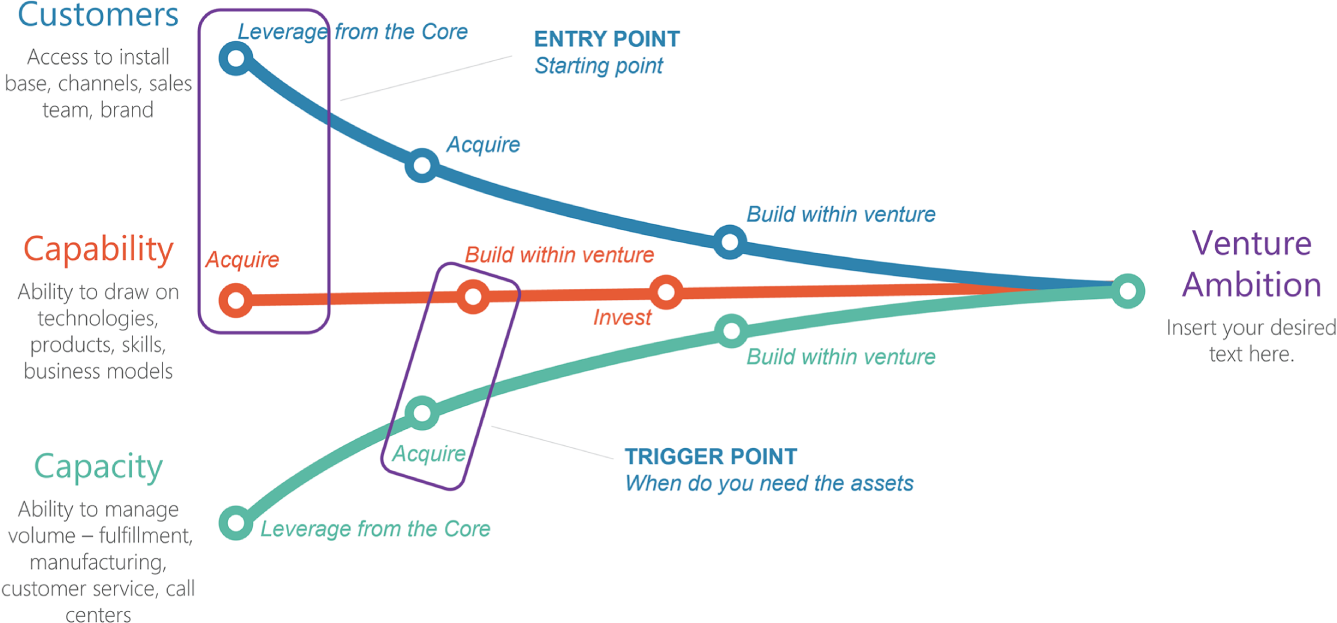

There are five steps that Corporate Explorers take to build a scaling path. We will illustrate these steps with our existing case examples, plus a new one from the US electronics retailer Best Buy. It is pursuing a strategy to move from retail and home electronics services toward home-based healthcare services, a market predicted to grow to over $350 billion by 2025.7

- Sketch a path to get capabilities, customers, and capacity to scale – Best Buy has watched as its former competitors, Circuit City and CompUSA, lost the battle against Amazon, and slipped into bankruptcy. Its new business, Best Buy Health (see Figure 6.2), would diversify the firm's revenues away from retail consumers and toward health insurance companies. Their aim was to provide elder care or “safe living systems” and remote medical care. These are lucrative markets. Motivated by a desire to leverage remote technologies to get patients out of hospitals fast, BestBuy saw the opportunity to attach itself to a growing technology and social trend. It planned to do this by assembling what Best Buy Health president Asheesh Sakensa called “the Lego pieces of what it takes to start building a scalable business.”8

Figure 6.2 Best Buy Health.

The first brick on the road was a capability to sell and install “smart home” services – connected devices for household security and automation. It hired special staff into its Geek Squad in-store installation team so that it could offer advice and installation of smart home devices. Best Buy then added more advanced Internet-connected wearable devices through its partnership with Vivint, a leading smart device provider. This gave it an opening into devices for the sick and elderly, and it added to that by acquiring GreatCall, which provides emergency call services to the elderly. GreatCall had 900,000 subscribers to their medical assistance service, activated at the touch of a button on mobile phones and other connected and wearable devices, like pendants and bracelets. Next, Best Buy partnered with Tytocare to begin offering customers an all-in-one device and telehealth platform for on-demand, remote medical exams. They have since expanded into new services such as social work, care orchestration, telemedicine, and even a Lyft ride partnership for the elderly.

- Select an entry point – Perhaps the hardest part of the scaling path is deciding where to start. Apple gets tremendous credit for disrupting the mobile phone industry with the iPhone. It started on this path a decade before it launched the phone itself. By 2001, Apple had already introduced the iPod, alongside the iTunes store. These laid the foundations for Apple so that they were able to optimize the business model of the iPhone, so when it launched in 2007 iTunes helped accelerate its adoption and has provided it with immense resilience ever since. iPhone had effectively created a bridge to the new service. The entry point should be adjacent to the company's current assets, otherwise the leap may be too great. For example, Best Buy started by offering a service to evaluate the homes of the elderly to identify any safety concerns and then make recommendations that may or may not involve using technologies from their stores. To do this, it leveraged its existing “Geek Squad” in store technical experts. At Analog Devices, Carlin had all the technical capabilities to realize his condition-based monitoring solution. However, he lacked knowledge about how electric motors are used in industrial manufacturing. Analog acquired a small Spanish company, Test Motors, that had a world-class team that had this domain knowledge, and they were able to significantly accelerate time to market for the solution.

- Select critical assets to build – Having established your entry point, you need to decide where to go next. Two questions can help with this decision. First, what are the elements of the scaling path that are essential to achieving some level of strategic control or defensibility in the market? AXA's entry point was to build a telemedicine capability. This they saw as the vital backbone for any future remote healthcare offering. Second, which of these elements can you put into the market most quickly? AXA first launched its telemedicine offering to its employees and then later added policyholders traveling internationally. This helped them in launching BonjourDocteur. They then made the service work by building out the next tier of critical assets, which allowed users to make appointments to see virtual doctors, download prescriptions, find a local pharmacy, and manage their own medical profile.

- Build out the path – As the venture matures from incubation to scaling, Corporate Explorers execute on the path by making decisions about what to build, what to buy, what to leverage from the core, and when to partner with other firms to get the assets that they need. AXA has continued to build out its capabilities, capacity, and customers over the past few years, including a partnership with Advance Medical and acquisitions of Maestro Health and Doctopsy and is now tapped into everything from women's and fertility medicine to senior wellness, to mental health. Its ultimate ambition to provide excellent, accessible, and streamlined services for all clients has never wavered, however, and that ambition has served as the guiding compass within the firm. Each step in AXA's scaling path has been designed to take it one step closer to its ambition.

- Decide on your trigger points – these are the moments at which you decide to execute on a plan to add access to customers, capability, or capacity. At LN, this was the decision to acquire technology capabilities by buying Seisint, and customer access with Choicepoint (see Figure 6.3). This requires a more detailed explanation, which we will give in the next section.

Trigger Points

A scaling path is a hypothesis about the assets a new venture will need. Scaling starts at ideation, so that there is an opportunity for continuous learning about what partnerships and acquisitions may help the venture go faster later in the journey. This learning never stops. The Corporate Explorer is looking for trigger points when it is time to add capacity or access to a customer group to the evolving business. For example, the Indian firm Reliance created a new 4G cellular phone company that created a market for mobile data access. They aimed to give app developers access to the enormous market of Indian urban professionals. Their scaling path included acquiring capability – they bought a company to get access to radio spectrum for broadband – and leveraging current assets to develop capacity. They built an entirely new phone network from scratch using construction technology (for 4G towers and fiber tunneling), leveraging skills from their petroleum refining and chemical businesses. When they launched, they took the unconventional approach of making unlimited data and voice free for three months, the logic being that this way they built an audience for app developers, thereby making the market commercially viable. This created a trigger point for further investment; when they had enough users, enough app developers, then the value of subscribing to the new service would increase.

Figure 6.3 LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

Balaji Bondili's trigger point was an external event: the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic drove consultants out of client premises and the usual weekly travel routine. It normalized remote working, removing all the barriers to adopting third-party freelance talent into Deloitte consulting teams. Bondili had built the capability – in his knowledge of the model, the legal frameworks for using third parties, and an understanding of how to frame problems – to scale. He had the capacity, with his external crowd partners. The pandemic brought him customers – Deloitte partners in urgent need of flexible talent. As he scaled, he pivoted, becoming as much a freelance labor source as crowd platform. He selected three Deloitte business areas on which to focus – analytics, mergers and acquisitions, and audit. He developed a partnership with Experfy, a third-party talent agency that gave him access to the talent. In a matter of months, Bondili went from developing a venture, to a scaled business with a capability that was transforming the model for business consultancy from within. Scaling is a decisive moment for a new venture. It is the point at which resources get committed to realize the ambition for the firm. This is a moment of real excitement for the team, as the long, lonely slog of proving a concept turns into the promise of hypergrowth.

Chapter Summary

Scaling a new business means assembling three key building blocks or assets: (1) customers (e.g., installed base, channels, sales teams), (2) organizational capabilities (e.g., technology, products, people, business models), and (3) organizational capacity (e.g., manufacturing, fulfillment, customer service).

Corporate Explorers have four different options for where these assets come from:

- Build – they can decide to create something in-house, developing out the minimum viable product into a full production version.

- Buy – they can find assets to acquire from existing companies, either startups or more mature enterprises.

- Leverage – they can access the assets of the core business and use them to help accelerate progress. Brand, customer access, technology, and back office assets are frequently critical to the success of new corporate ventures.

- Partner – creating ecosystem relationships that are mutually beneficial, this includes joining multisided platforms, such as app stores and exchanges, such as salesforce.com.

These choices on what assets are needed and where to get them become a scaling path – a schematic of the steps the new venture will take to go from validated business idea to fully operational, revenue generating entity. We recommended developing a first hypothesis for a scaling path in ideation and continuing to iterate it as you learn more.

Notes

- 1. Michael J. Mauboussin and Dan Callahan, “Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look,” Morgan Stanley, August 4, 2020.

- 2. Alan Lewis and Dan McKone, “So Many M&A Deals Fail Because Companies Overlook This Simple Strategy,” Harvard Business Review, May 10, 2016, https://hbr.org/2016/05/so-many-ma-deals-fail-because-companies-overlook-this-simple-strategy.

- 3. Yaakov Weber, Shlomo Tarba, and Christina Öberg, “M&A Paradox,” in Comprehensive Guide to Mergers and Acquisitions (FT Press, 2013), 3–12.

- 4. Lewis and McKone, “So Many M&A Deals Fail,” accessed February 11, 2019.

- 5. Charles C. O'Reilly III, J. Bruce Harreld, and Michael L. Tushman, “Organizational Ambidexterity: IBM and Emerging Business Opportunities,” California Management Review, July 1, 2009.

- 6. Jerome Buvat et al., Digital Talent Gap, Capgemini Digital Transformation Institute, June–July 2017.

- 7. BCC Report, Elder Care and Assistive Devices, BCC Publishing, January 2021.

- 8. Daphne Howland, “Best Buy Goes on the Offensive with New Growth Strategy,” Retail Dive, September 17, 2017, https://www.retaildive.com/news/best-buy-goes-on-the-offensive-with-new-growth-strategy/505322/ (accessed May 11, 2020).